After a herculean data-gathering effort, in this issue of Blood, Aldenhoven and colleagues from Europe and North America provide an eye-opening assessment of long-term neurocognitive, organ, joint, and tissue function after allogeneic transplantation of children with mucopolysaccharidosis type I–Hurler syndrome (MPS-IH), along with an analysis defining a path to better these outcomes.1

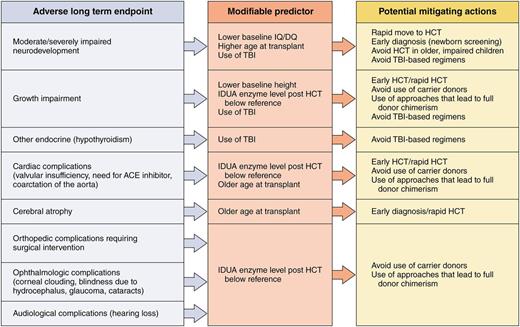

Potential actions that healthcare providers/public health systems could take to mitigate poor outcomes in patients with Hurler syndrome undergoing transplantation. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

Potential actions that healthcare providers/public health systems could take to mitigate poor outcomes in patients with Hurler syndrome undergoing transplantation. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

In an essay entitled The Star Thrower, philosopher Loren Eiseley paints a picture of a perilous seashore on which thousands of sea creatures are washed up and left to die. In the midst of what one could conceive as carnage, a lone figure picks up starfish, one by one, and throws them back into the ocean so they can survive.2 Is this futile? In the face of ongoing destruction, does this action make a difference? Caring for children with mucopolysaccharidoses, one can often feel like the Star Thrower, trying to nurture not only life but quality of life in children with a relentless disease that affects the brain, joints, heart, lung, liver, and skeletal and other tissues and is only partially treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Which of the many tissues in these children’s bodies are we preserving with HCT, and how can we do better?

Earlier work by this group of investigators and others has documented a steady increase in survival3,4 and highlighted the importance of transplanting children as young as possible, as developmental loss is incremental.5,6 Another key association that has been made is the presence of full-donor chimerism with iduronidase (the enzyme missing in MPS-IH) levels in the normal range, suggesting that approaches and stem cell sources that lead to full chimerism are important.7 Use of sibling donors who are asymptomatic carriers of the gene defect also seems to result in lower iduronidase levels,8 and transplant centers are now often passing on matching sibling donors in favor of a noncarrier unrelated donor. But is it worth forgoing the use of a carrier sibling in favor of unrelated donors, especially cords, often associated with high risks for transplant-related mortality?

The data put forward by Aldenhoven et al strongly suggest that such a previously unorthodox choice of using an unrelated cord over a matched sibling may be justified. The figure shows adverse long-term outcomes noted by the authors in children transplanted for MPS-IH and outlines modifiable predictors with potential actions that transplant physicians could take that may make a difference in outcome.1 For many key organ/tissue outcomes (growth impairment and orthopedic, cardiac, ophthalmological, and audiological complications), the key risk factor was a post-HCT iduronidase level below local reference range. Chances of better outcomes in so many areas are so heavily dependent on this level that it seems to be of highest importance to avoid carrier donors and use approaches that maximize chances of full-donor chimerism. Some of the other modifiable predictors are very easy to address (avoid total body irradiation), but some take effort and organization on the part of physicians caring for the patient (rapid referral and receiving HCT as soon as possible). The most challenging, and perhaps the most important, of the factors, however, is arriving at a diagnosis very early in life, before significant neurological and other organ damage. Too many of these patients are diagnosed at 1 to 2 years of age, by which point significant damage to the brain and tissues has occurred in most patients. In addition, patients can worsen after HCT, before stabilization. Patients transplanted with high intelligence quotient/developmental quotient and minimal organ/skeletal defects clearly do better both short- and long-term. This is a strong argument for the development and implementation of newborn screening techniques for MPS-IH that are cost-effective and feasible.

The better knowledge of modifiable factors noted in this article that can have an effect and improve the lives of children with this disease allows transplant Star Throwers to be hopeful in the face of a disease that challenges the best of us.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.