Key Points

KIR2DL5B is associated with poor molecular response and transformation-free survival in CML patients enrolled to the TIDEL-II study.

KIR genotyping would select out high risk CML patients at baseline and allow better targeting of novel interventions.

Abstract

Killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs) on natural killer (NK) cells have been shown to predict for response in chronic phase-chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML) patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. We performed KIR genotyping in 148 newly diagnosed CP-CML patients treated with a novel sequential imatinib/nilotinib strategy aimed at achievement of optimal molecular responses at defined time points. We found the presence of KIR2DL5B to be associated with inferior transformation-free survival and event-free survival and an independent predictor of inferior major molecular response (BCR-ABL1 ≤0.1%) and molecular response 4.5 (BCR-ABL1 ≤0.0032%). This suggests a critical early role for NK cells in facilitating response to imatinib that cannot be overcome by subsequent intensification of therapy. KIR genotyping may add valuable prognostic information to future baseline predictive scoring systems in CP-CML patients and facilitate optimal frontline treatment selection.

Introduction

The majority of chronic phase-chronic myeloid leukemia (CP-CML) patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have excellent transformation-free survival (TFS), with only 2% to 7% progressing to accelerated phase or blast crisis.1 Prognostic biomarkers that reliably identify these high-risk patients remain elusive, although individual immune response profiles may contribute to the differences in treatment outcomes.

Killer immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs), expressed by natural killer (NK) cells, are an integral element of the innate immune response.2 The KIR genetic locus has 16 highly polymorphic genes, coding for either activating or inhibitory KIRs. KIRs participate in NK cell-mediated cell killing of virally infected or tumor cells, in which the ligand may be altered or missing. Normal host cells with appropriate ligand expression are protected by interaction through the inhibitory KIRs.3

KIR alleles are highly individualized, and each of the 16 genes may either be present or absent. These genes are organized into 2 broad haplotypes: A and B.3 KIR genotype variations are associated with cancer treatment outcomes and predisposition to immune disorders.4,5 Importantly, donor B haplotypes are associated with improved survival in the context of unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplants for acute myeloid leukemia.6

In this study, we investigated the link between KIR genotypes and treatment outcomes in CP-CML patients treated in the Therapeutic Intensification in De Novo Leukaemia (TIDEL-II) study, using dose adapted frontline imatinib followed by rapid switching to nilotinib for failing to achieve consensus optimal responses.7,8

Study design

In TIDEL-II, all 210 patients started treatment with imatinib 600 mg/day.9 The imatinib dose was escalated to 800 mg/day if serum imatinib trough levels at day 22 were <1000 ng/mL. Patients who failed to achieve any of the predetermined molecular targets (BCR-ABL1 ≤10%, ≤1%, and ≤0.1% at 3, 6, and 12 months respectively, on the international scale) were switched to nilotinib 400 mg twice daily with or without an antecedent trial of imatinib 800 mg/day. KIR genotyping was performed in 148 patients (samples unavailable in 62 patients) with the Genotyping SSP Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Genotypes were correlated with molecular response and survival outcomes. Survival probabilities were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method.10 Cumulative incidence probabilities were calculated using Fine and Gray’s method, with study withdrawal for any reason as competing risks.11 The Akaike information criterion was used for optimum model selection in competing risk multivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were done using R.12-14 This research was approved by the institutional Human Research Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results and discussion

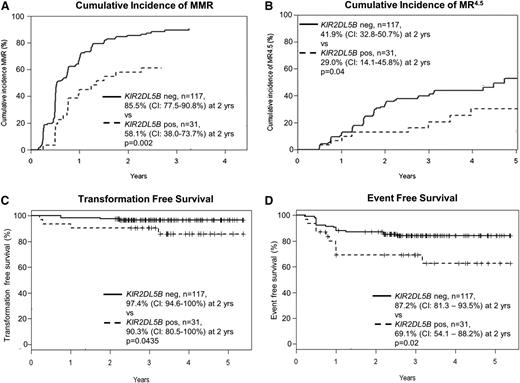

Characteristics and outcomes of the 148 patients in the KIR substudy were similar to the TIDEL-II cohort in entirety (supplemental Table 1 available on the Blood Web site). Univariate analyses correlated achievement of major molecular response (MMR; BCR-ABL1 ≤0.1%) with early molecular response (EMR; BCR-ABL1 ≤10% at 3 months), Sokal score, and the absence of KIR2DL5B, KIR2DS3, and KIR2DL2 (Table 1). EMR is a particularly strong predictor of subsequent molecular outcomes in our cohort, as demonstrated in other studies.8 Among different KIR genotypes, patients who had the KIR2DL5B gene (KIR2DL5BPOS) had inferior achievement of MMR (Figure 1A) and molecular response 4.5 (MR4.5; BCR-ABL1 ≤ 0.0032%; Figure 1B). KIR2DL5BPOS was also associated with inferior TFS and event-free survival (EFS) (Figure 1C-D; supplemental Tables 2 and 3) but not overall survival (data not shown).

Correlation between KIR2DL5B and treatment outcomes in patients treated with imatinib and nilotinib in the TIDEL-II study.KIR2DL5BPOS patients have inferior achievement of molecular responses: (A) cumulative incidence of MMR and (B) MR4.5. KIR2DL5BPOS patients also have inferior TFS and EFS compared with KIR2DL5BNEG patients. (C) TFS events include transformation to accelerated phase and blast crisis, as well as death from any cause. (D) EFS events include TFS events and loss of MMR or BCR-ABL1 increasing to a level >1% from a nadir ≤1%, kinase domain mutations, and discontinuation of TIDEL-II treatment (imatinib and/or nilotinib) for any cause. The difference in overall survival as segregated by KIR2DL5B status is not statistically significant (data not shown).

Correlation between KIR2DL5B and treatment outcomes in patients treated with imatinib and nilotinib in the TIDEL-II study.KIR2DL5BPOS patients have inferior achievement of molecular responses: (A) cumulative incidence of MMR and (B) MR4.5. KIR2DL5BPOS patients also have inferior TFS and EFS compared with KIR2DL5BNEG patients. (C) TFS events include transformation to accelerated phase and blast crisis, as well as death from any cause. (D) EFS events include TFS events and loss of MMR or BCR-ABL1 increasing to a level >1% from a nadir ≤1%, kinase domain mutations, and discontinuation of TIDEL-II treatment (imatinib and/or nilotinib) for any cause. The difference in overall survival as segregated by KIR2DL5B status is not statistically significant (data not shown).

KIR2DL2POS and KIR2DS3POS were also associated with inferior achievement of MMR and are commonly coinherited with KIR2DL5B as an allele.15 In our cohort, all 31 patients positive for KIR2DL5B also had the KIR2DL2 gene, and 27 of 31 (87%) also had the KIR2DS3 gene (supplemental Figure 1). These frequencies are similar to data from the Allele Frequency Database compared with predominantly Caucasian cohorts.16,17 Due to linkage disequilibrium between KIR genes, we suspected the prognostic power of KIR2DL2 and KIR2DS3 were secondary to their association with KIR2DL5B. Indeed, a multivariate analysis including the 3 KIR genotypes, Sokal score, and EMR as variables demonstrated the KIR2DL5B status and EMR to be the only independent predictors for achievement of MMR (Table 1). Consistent with an independent relationship, there was no correlation between KIR2DL5B genotype and EMR: 5 of 31 KIR2DL5BPOS patients failed to achieve EMR compared with 13 of 116 KIR2DL5BNEG patients (16% vs 11%, P = .54, EMR data missing for 1 patient).

Ours is the first study showing the prognostic significance of KIR genotypes in patients treated (sequentially) with nilotinib. In TIDEL-II, patients at risk of inferior outcomes were rapidly switched from imatinib to nilotinib. KIR2DL5BPOS and KIR2DL5BNEG patients who received nilotinib treatment were similar in proportion (26% vs 21%). However, their outcomes are different: 1 of 8 (13%) and 11 of 25 (56%) subsequently achieved MMR in the KIR2DL5BPOS and KIR2DL5BNEG groups, respectively (supplemental Table 4). Our findings suggest that even with the potent second-generation TKI nilotinib, KIR genotypes, a predetermined genetic host factor, may still be one of the most discriminatory prognostic markers available at baseline. Although the biological mechanism that underpins this observed association remains to be elucidated, KIR2DL5B encodes an inhibitory “orphan” KIR receptor (its ligand is unknown),18 but its absence may increase efficiency of NK-mediated killing of leukemic stem cells. The importance of immune responses in CML disease control with TKI therapy is consistent with effects seen with allogeneic stem cell transplant, donor lymphocyte infusions, and interferon-alfa treatment, in which the therapeutic effect is wholly or partially secondary to T- and NK-cell activity.19,20 Interestingly, increased numbers of oligoclonal T and NK cells occur with dasatinib therapy and are associated with a better prognosis.21 Additionally, certain KIR genotypes have previously been reported to be overrepresented in CML patients.22 However, KIR genotype frequencies observed in our cohort are similar to those observed in other Caucasian populations reported in the Allele Frequency Database.

Several groups have claimed a link between KIR genotypes and treatment response in CP-CML. In a British cohort treated with imatinib 400 mg/day, KIR2DS1NEG was correlated with superior achievement of complete cytogenetic response; KIR2DL5B was correlated with response by univariate analysis only in this study.23 However, in a follow-up report, there was no correlation between KIR genotypes and outcomes in their dasatinib-treated patients.24 In contrast, Kreutzman et al25 showed an association between superior molecular response and KIR2DL5A/BNEG in a dasatinib-treated cohort. Observations of the British imatinib and Scandinavian cohorts, together with the current study, demonstrate the strongest link between KIR2DL5B of the KIR cluster and treatment outcomes.

EMR is also known to be strongly associated with treatment outcomes and may also be used to guide treatment decisions. The independent prognostic significance of EMR and KIR suggests their prognostic information may be additive. However, EMR information is only available 3 months after treatment commencement. In contrast, KIR2DL5B can identify, at baseline, the 20% of patients with a transformation risk of ∼10% over 2 years vs the 80% of patients with a transformation risk of <3%. Incorporation of KIR2DL5B in future baseline prognostic scores, together with other predictive markers, may enable targeted interventions to improve outcomes at the earliest available opportunity, if the presence and magnitude of KIR2DL5B’s prognostic influence can be further validated and confirmed in prospective studies. Additionally, further understanding the role of KIR and cytotoxic cells in eradicating leukemic clones will translate to specific salvage treatment strategies aimed at boosting immune responses in poor-risk patients thus identified, such as the addition of interferon-alfa.

Presented at the American Society of Hematology Meeting, San Francisco, CA, December 6-9, 2014.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This paper presents results of a correlative study of TIDEL-II, a clinical trial sponsored by the Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group. A list of contributing investigators of this clinical study appears in supplemental Materials. The authors acknowledge the ongoing assistance of Stephanie Arbon, Bronwyn Cambareri, Jodi Braley, and all the site coordinators of the TIDEL-II study.

This study was supported financially by Novartis, Australian National Health and Medical Research Council grant APP1059165, and the Royal Adelaide Hospital Contributing Haematologists’ Committee.

Novartis had no role in the analysis or presentation of these data.

Authorship

Contribution: D.T.Y. contributed to research design, gathered and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript; S.B. and D.L.W. contributed to research design and critically reviewed the manuscript; T.P.H. and A.S.Y. contributed to research design, supervised the research, and critically reviewed the manuscript; and C.T. and L.V. performed the research and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.L.W., D.T.Y., and T.P.H. acted as a consultant or advisor to and received research funding and honoraria from Novartis, BMS, and Ariad; T.P.H. acted as a consultant or advisor to and received honoraria from Pfizer; S.B. acted as a consultant or advisor to and received research funding and honoraria from Novartis and BMS and received research funding from Ariad; A.S.Y. received research funding and honoraria from Novartis. D.T.Y. received scholarship funding from the Leukaemia Foundation of Australia and the Royal Adelaide Research Foundation AR Clarkson scholarship. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Agnes Yong, SA Pathology, PO Box 14, Rundle Mall, Adelaide, SA 5000, Australia; e-mail: agnes.yong@sa.gov.au.