In this issue of Blood, Fischer et al present long-term follow up of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)8 study, which established fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) as the gold standard for initial therapy of fit patients with CLL.1

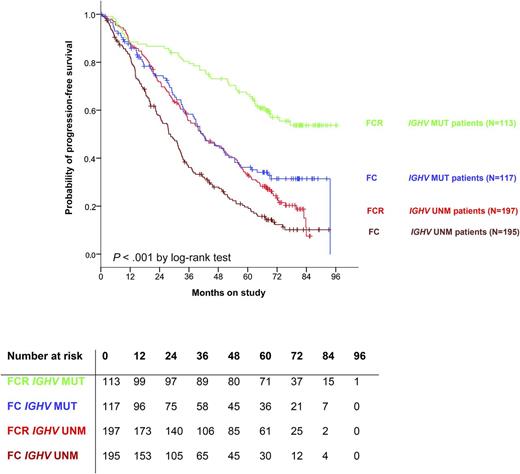

PFS is superior for patients with IGHV-mutated disease compared with unmutated. As well, for patients with IGHV-mutated disease treated with FCR, relapses appear to be rare after 7 years, suggesting that there may be patients cured by this regimen. MUT, mutated; UNM, unmutated. See Figure 2A in the article by Fischer et al that begins on page 208.

PFS is superior for patients with IGHV-mutated disease compared with unmutated. As well, for patients with IGHV-mutated disease treated with FCR, relapses appear to be rare after 7 years, suggesting that there may be patients cured by this regimen. MUT, mutated; UNM, unmutated. See Figure 2A in the article by Fischer et al that begins on page 208.

Therapy for CLL is currently undergoing an exciting paradigm shift with the advent and widespread use of the B-cell receptor signaling inhibitors ibrutinib and idelalisib, as well as the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax currently in clinical trials. Idelalisib and ibrutinib are currently a standard of care for previously treated patients based on data from phase 3 trials demonstrating superior progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) as compared with standard therapies.2,3 Although limited data exists for these agents in previously untreated disease, preliminary data with ibrutinib is especially provocative, with an estimated 96% PFS at 33 months.4 Clinical studies such as the intergroup trial E1912 (#NCT02048813) are ongoing to compare these novel agents to standard FCR in the upfront setting, so this is a particularly fitting time for an update on the long-term experience with FCR.

The current article reports on 5.9 years of follow-up from treatment with either fludarabine and cyclophosphamide (FC) or FCR, with an emphasis on late-term adverse events as well as efficacy of the regimens. Not surprisingly, FCR remains superior to FC. In the FCR group, median PFS was 56.8 months and OS has not yet been reached. Late-onset malignancies are highlighted and include a 4.7% incidence of Richter transformation and 1.6% incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML). Myeloid neoplasia was not different between the groups; however, there was a higher incidence of Richter in the FC arm. Solid tumors were observed at a similar rate to the general population. This incidence of MDS/AML is lower than has been reported by the MD Anderson group with FCR,5,6 perhaps relating to the duration of follow-up. It has yet to be determined how these long-term toxicities compare with kinase inhibitors, but this will be an important question for the future.

This study also addresses genomic risk groups that are pertinent to chemoimmunotherapy. Patients with unmutated immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV), del(17p), del(11q), high thymidine kinase, mutated TP53, and mutated SF3B1 all show inferior PFS. Unmutated IGHV and del(17p) are the strongest negative prognostic indicators, and indicate a group of patients where alternative therapies, such as ibrutinib, should be considered. Conversely, however, for patients with mutated IGHV, there is a reasonable expectation of a durable PFS with a median PFS not reached for patients treated with FCR (see figure). Importantly, very few relapses appear after about 7 years. This is particularly interesting as it corroborates data from MD Anderson,6 where there is also a “shoulder” in the PFS curve at this point, and no new relapses were seen in this IGHV-mutated subgroup after 10.4 years, suggesting that there are patients who may be cured by this regimen.

FCR is certainly not an appropriate therapy for all CLL patients, especially those who are older and less fit. Multiple publications have shown no advantage of fludarabine over chlorambucil in older patients,7,8 and preliminary results from the recent German CLL Study Group (ie, GCLLSG10 study) of FCR vs bendamustine/rituximab show superior PFS for FCR except for patients age 65 years of greater, where the two regimens appear equivalent.9 Early toxicities with FCR and secondary malignancies, which may be more common or less treatable in the elderly, make less intensive regimens of significant interest for this group.

The long-term data presented in this study, especially when taken together with the data from MD Anderson, strongly suggest that some low-risk patients are being cured with FCR chemoimmunotherapy, and this regimen should be offered to young, fit patients who do not wish to participate in a clinical trial. Important open questions remain, however. With excellent options for second-line therapy with kinase inhibitors, is it imperative to choose the frontline therapy with the longest PFS, or is frontline therapy with less toxicity more desirable in some circumstances? As well, if kinase inhibitors become an option for frontline therapy, does the potential for cure and therapy interruption outweigh the risks of short- and long-term toxicity? As we move forward with an increasing armamentarium of targeted therapies in CLL, these questions will become more relevant, and future clinical trials will be needed to address these. The fact that these questions exist, though, highlight how far the field of CLL therapy has advanced over the past decade and should instill hope for our CLL patients in the years to come.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.