Key Points

Based on their impact on treatment and survival, ACAs in CML were stratified into good and poor prognostic groups.

ACAs in the good prognostic group showed no adverse impact on survival when they emerged from chronic phase or at the initial CML diagnosis.

Abstract

Clonal cytogenetic evolution with additional chromosomal abnormalities (ACAs) in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is generally associated with decreased response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy and adverse survival. Although ACAs are considered as a sign of disease progression and have been used as one of the criteria for accelerated phase, the differential prognostic impact of individual ACAs in CML is unknown, and a classification system to reflect such prognostic impact is lacking. In this study, we aimed to address these questions using a large cohort of CML patients treated in the era of TKIs. We focused on cases with single chromosomal changes at the time of ACA emergence and stratified the 6 most common ACAs into 2 groups: group 1 with a relatively good prognosis including trisomy 8, −Y, and an extra copy of Philadelphia chromosome; and group 2 with a relatively poor prognosis including i(17)(q10), −7/del7q, and 3q26.2 rearrangements. Patients in group 1 showed much better treatment response and survival than patients in group 2. When compared with cases with no ACAs, ACAs in group 2 conferred a worse survival irrelevant to the emergence phase and time. In contrast, ACAs in group 1 had no adverse impact on survival when they emerged from chronic phase or at the time of CML diagnosis. The concurrent presence of 2 or more ACAs conferred an inferior survival and can be categorized into the poor prognostic group.

Introduction

Although defined by t(9;22)(q34;q11.2)/BCR-ABL1, chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) commonly shows additional chromosomal abnormalities (ACAs), especially during accelerated phase (AP) and blast phase (BP). Despite the association between ACAs and disease progression in CML,1 the role of each individual ACA is largely unknown, and a risk-based classification system that is used in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is currently lacking in CML.

In MDS and AML, chromosomal abnormalities have been well studied and widely used to stratify patients based on their impact on treatment and survival. In the most recently revised International Prognostic Scoring System for MDS, cytogenetic changes were stratified into 5 categories: very good, good, intermediate, poor, and very poor.2 In AML, chromosomal changes are also categorized using a similar stratification strategy.3 In contrast, a risk-based strategy to stratify chromosomal abnormalities in CML does not exist. Many studies including European LeukemiaNet4 have classified ACAs in CML into “major” and “minor” route changes.5 The major route ACAs are the most common chromosomal abnormalities (>10% of cases with ACAs) and include trisomy 8, an extra Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), i(17)(q10), and trisomy 19. Other less common ACAs belong to minor route ACAs. Of note, this classification is solely based on the frequency of ACAs and does not necessarily reflect their roles in treatment response and prognosis. Chromosomal changes identified during clonal evolution of CML are highly heterogeneous, and it seems reasonable to hypothesize that different chromosomal changes play completely different roles; some simply reflect genetic instability induced by continuous BCR-ABL1 activation, whereas others may trigger disease progression and treatment resistance.6,7 Thus, it is necessary to establish a stratification system in CML to classify ACAs into different groups based on their impact on treatment and survival rather than their prevalence. Another justification for such stratification is the relatively high frequency of ACAs during disease progression. Although CML is defined by the BCR-ABL1 gene fusion,8 it frequently presents with other concurrent cytogenetic changes during disease progression.5,9,10 Approximately 30% of cases in AP and 80% to 90% of cases in BP have ACAs.9,11

Although previous studies have indicated that the major route ACAs4,12-14 but not the minor route ACAs12 are associated with poorer prognosis, these studies were often confounded by the concurrent presence of multiple chromosomal changes. Indeed, in our recent study,15 we reported that trisomy 8, one of the major route ACAs, is actually associated with a good tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) response and favorable prognosis when it occurs alone. However, when accompanied by other concurrent chromosomal changes, the favorable impact of trisomy 8 is mitigated, and patients indeed have a poorer prognosis. Previous studies have shown that as a group, the minor route ACAs have no adverse effect on TKI treatment response and prognosis.12 However, this may be an oversimplification because the group of minor route ACAs is quite heterogeneous and includes a diversity of chromosomal changes whose individual prognostic impact is difficult to analyze because of their relative rarity. In our recent studies, we demonstrated that some minor route changes such as 11q23/MLL16 and 3q26 rearrangements17 are actually associated with TKI resistance and poor prognosis. Thus, the classification of ACAs into major and minor route changes does not reliably reflect their roles in prognosis. A better classification system needs to be explored.

In this study, we aimed to study the role of individual common ACAs in CML patients using a systematic approach by which ACAs are stratified based on their impact on survival and treatment response. We focused our analysis on CML patients with single ACAs to avoid the confounding impact of 2 or more coexisting ACAs. We analyzed the frequency of ACAs, the phase when the ACAs emerged, and their impact on TKI response and survival.

Materials and methods

Case selection and clinical information collection

We evaluated CML patients admitted to our hospital in the era of TKI therapy. Depending on the time of admission and whether patients were enrolled in clinical trials, they were offered either imatinib or a second-generation TKI such as nilotinib or dasatinib. The third-generation TKI ponatinib was used for targeting T315I mutation. For CML diagnosis and disease monitoring, bone marrow aspirate with conventional G-banding cytogenetic analysis was generally performed at baseline, every 3 months for the first year, and every 6 to 12 months thereafter. Real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was also routinely performed using bone marrow aspirate and/or peripheral blood. Conventional cytogenetic data were carefully reviewed, and cases with ACAs were further analyzed. Their corresponding clinical parameters, including the date and phase of ACA emergence, TKI regimens after ACA emerged, treatment response, and follow-up data, were obtained. Patients with inadequate follow-up karyotyping data were excluded for the evaluation of TKI response. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Of note, Ph-positive de novo acute lymphoblastic leukemia was excluded from this study. The following chromosomal changes were not considered as ACAs: Ph variants (balanced 3- or 4-way translocations); chromosomal changes in Ph-negative cells; constitutional chromosomal changes such as pericentric inversion of chromosome 9; structural abnormalities or chromosome gains in <2 cells; and chromosome loss in <3 cells. In the latter 2 conditions, chromosomal changes were counted as clonal if the changes were confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization studies or in a following cytogenetic study.

Besides +der(9;22)(q34;q11.2), an extra Ph also includes der(22)idic(22)(p11.2)t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), ider(22)(q10)t(9;22)(q34;q11.2), and der(22)idic(22)(q11.2)t(9;22)(q34;q11.2); −7/del(7q) includes monosomy 7 and cases with 7q deletion. The 3q26.2 rearrangements include inv(3)(q21q26.2), t(3;3)(q21;q26.2), t(3;21)(q26.2; q22), and other rare balanced translocations involving the 3q26.2 region.

Criteria for AP and BP

The criteria proposed by the European LeukemiaNet were used, and similar criteria have been widely used by others.12,13,16,18 Briefly, AP is defined as any of the following criteria: (1) 15% to 29% blasts in peripheral blood or bone marrow; (2) 20% or more basophils in peripheral blood or bone marrow; (3) 30% or more blasts plus promyelocytes in peripheral blood or bone marrow, with blasts <30%; (4) platelets <100 × 109/L unrelated to therapy; or (5) clonal evolution with ACAs. BP is defined as 30% or more blasts in peripheral blood or bone marrow, or extramedullary blast proliferation.

In this study, we designated the emergence phase of ACAs based on whether there were other concurrent AP features. In detail, we defined that ACAs emerged from chronic phase (CP) when no other AP features were present, and ACAs emerged from AP when ACAs were accompanied with other AP features.

Definition of cytogenetic and molecular response

The definitions of complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) and major molecular response (MMR) were described previously.16

Survival analysis

The Kaplan and Meier method was used to build survival curves, and the log-rank test was performed to evaluate the differences in survival. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from 2 different starting time points: (1) date of ACA emergence (OS after ACAs emergence) and (2) date of CML diagnosis (OS after CML diagnosis). The end time point is the date of last follow-up or death. Fisher’s exact test was performed to assess the difference of various clinical parameters among groups in Table 1. A value of P ≤ .05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

The distribution of ACAs in CML and their impact on survival

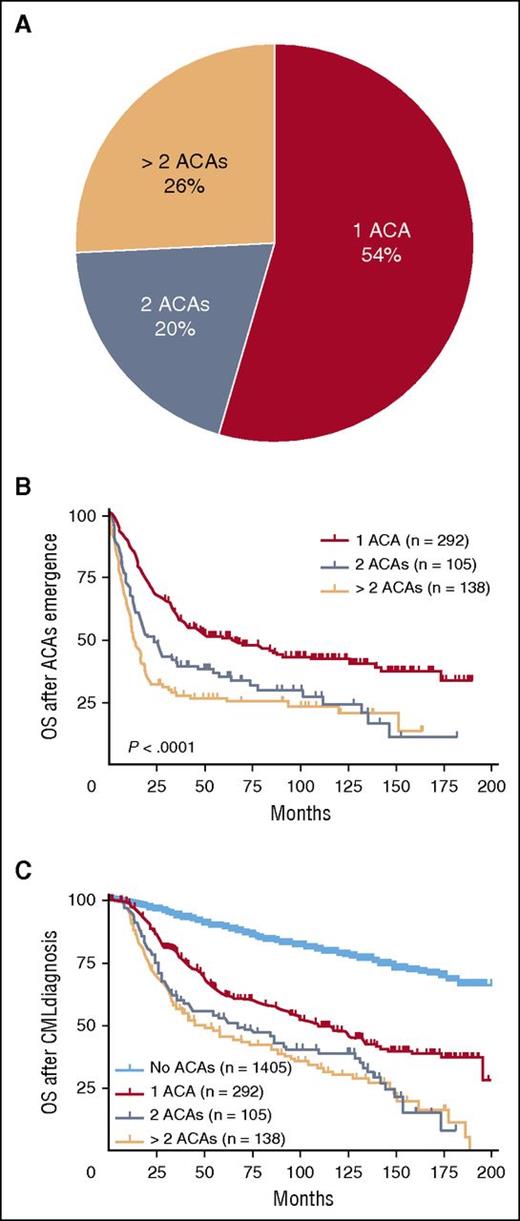

In total, 2013 CML cases with available karyotyping analysis were reviewed for this study, of which 608 (30%) patients had developed ACAs. Among these 608 cases, 535 (88%) cases had adequate clinical information to determine the exact time of ACA emergence. At the time of initial ACA emergence, 54% (292/535) of cases had a single ACA, 20% (105/535) had 2 ACAs, and 26% (138/535) had multiple (>2) ACAs (Figure 1A).

The distribution of ACAs in CML and their impact on survival. Cases with ACAs were stratified based on the numbers of ACAs at the time of initial ACA emergence (A). The impact of ACAs on survival was analyzed. Date of ACAs emergence was used as the starting time point in panel B (OS after ACAs emergence), and date of CML diagnosis was used as the starting time point in panel C (OS after CML diagnosis). Of note, survival analysis in this figure included all stages of disease (CP, AP, and BP).

The distribution of ACAs in CML and their impact on survival. Cases with ACAs were stratified based on the numbers of ACAs at the time of initial ACA emergence (A). The impact of ACAs on survival was analyzed. Date of ACAs emergence was used as the starting time point in panel B (OS after ACAs emergence), and date of CML diagnosis was used as the starting time point in panel C (OS after CML diagnosis). Of note, survival analysis in this figure included all stages of disease (CP, AP, and BP).

We studied the impact of ACAs on OS starting with the evaluation of OS after ACA emergence. As shown in Figure 1B, patients with 2 or more ACAs had a worse survival than patients with single ACAs (1 vs 2 ACAs, P < .0001; 1 vs >2 ACAs, P < .0001). There was no significant difference in OS between patients with 2 vs >2 ACAs (P = .11). Next we analyzed OS after CML diagnosis, and similarly herein patients with 2 or more ACAs had a worse survival than patient with single ACAs (1 vs 2 ACAs, P = .001; 1 vs >2 ACAs, P < .0001) (Figure 1C). No difference in OS was found between patients with 2 vs >2 ACAs (P = .56). When compared with patients with no ACAs, patients with ACAs showed a worse survival (Figure 1C: no ACA vs 1 ACA, P < .0001; no ACA vs 2 ACAs, P < .0001; no ACA vs >2 ACAs, P < .0001).

Type and frequency of ACAs in patients with single ACAs

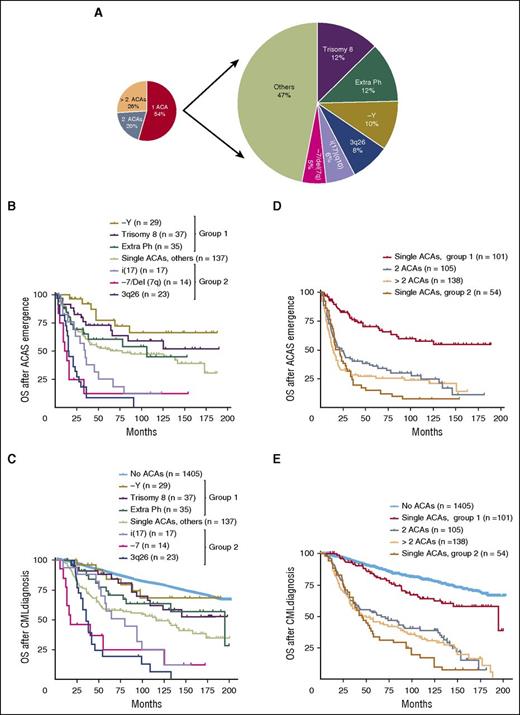

As the coexistence of multiple ACAs confounds the study of the prognostic role of individual chromosomal changes, to address the latter knowledge gap we turned our attention to the group of patients who had a single ACA at the time of initial emergence. Among 292 cases with single ACAs, trisomy 8 was the most common cytogenetic change (37/292, 12%), followed by an extra Ph (35/292, 12%), −Y (29/292, 10%), 3q26 rearrangements (23/292, 8%), i(17)(q10) (17/292, 6%), and −7/del (7q) (14/292, 5%) (Figure 2A; Table 1). As −Y only occurs in male patients, the rate of −Y increased to 15% (29/188) when only male patients were included. These 6 ACAs represent 53% of all cases with single ACAs. Their clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The remaining less common chromosomal changes included +21 (5/292, 1.7%), del(13q) (4/292, 1.4%), inv(16) (4/292, 1.4%), and other rare cytogenetic abnormalities. Trisomy 19, one of major route chromosomal changes, uncommonly presented as the sole ACA and was only identified in 3 of 292 (1%) cases.

The stratification and survival impact of ACAs in CML. In cases with single ACAs, the types and frequencies of common ACAs were listed (A), and survival analysis following ACAs emergence (B) and CML diagnosis (C) was performed. In panel C, patients with no ACAs were included as a control. (D-E) Survival comparison between patients with 2 or more ACAs and patients with single ACAs. In patients with single ACAs, cases within each group were combined for survival analysis. Group 1 included patients with −Y, trisomy 8, and an extra Ph. Group 2 included patients with i(17), −7/Del(7q), and 3q26 rearrangements. Of note, survival analysis in this figure included all stages of disease (CP, AP, and BP).

The stratification and survival impact of ACAs in CML. In cases with single ACAs, the types and frequencies of common ACAs were listed (A), and survival analysis following ACAs emergence (B) and CML diagnosis (C) was performed. In panel C, patients with no ACAs were included as a control. (D-E) Survival comparison between patients with 2 or more ACAs and patients with single ACAs. In patients with single ACAs, cases within each group were combined for survival analysis. Group 1 included patients with −Y, trisomy 8, and an extra Ph. Group 2 included patients with i(17), −7/Del(7q), and 3q26 rearrangements. Of note, survival analysis in this figure included all stages of disease (CP, AP, and BP).

Treatment response and survival analysis of patients with single ACAs

We focused on the 6 most common ACAs listed in Table 1 and studied their impact on treatment response and survival. The number of patients who received TKIs after ACAs emerged was as follows: trisomy 8, 30/37 (81%); −Y, 28/29 (97%); an extra Ph, 25/35 (71%); i(17)(q10), 16/17 (94%); −7/del(7q), 12/14 (86%); and 3q26.2 rearrangements, 21/23 (91%). Cytogenetic and molecular responses were evaluated alongside detailed clinical information available in these patients. In some cases, especially those with ACAs emerging from BP, patients often received other concurrent therapies. To avoid confusion, these cases were excluded from the analysis of TKI response. As shown in Table 1, the 6 most common ACAs can be divided into 2 groups based on their impact on TKI treatment response. The first group included trisomy 8, −Y, and an extra Ph with a relatively good response; the second group included i(17)(q10), −7/del(7q), and 3q26.2 rearrangements with a relatively poor response. For simplicity, these 2 groups were designated as group 1 and group 2, respectively (Table 1). The detailed statistical analysis to compare treatment response among patients with different ACAs was performed, and the results with P values are listed in supplemental Tables 1 and 2 (available on the Blood Web site).

We then compared their association with survival. Consistent with the TKI response pattern shown in Table 1, patients in group 1 had a better OS than patients in group 2 (Figure 2B-C). Other less common ACAs were heterogeneous and, as a group, were associated with an impact on survival similar to an extra Ph (Figure 2B-C). Detailed statistical analysis to compare survival between patients with different ACAs was performed, and the results with P values are listed in supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

In Figure 2C, we included patients with no ACAs and aimed to determine whether ACAs in group 1 were associated with an adverse prognosis. Patients with −Y showed no significant survival difference from patients with no ACAs (no ACAs vs −Y, P = .66), whereas trisomy 8 and an extra Ph were associated with a worse prognosis (no ACAs vs trisomy 8, P = .05; no ACAs vs an extra Ph, P = .01).

We then included patients with 2 or more ACAs and compared their survival with patients with single ACAs. For patients with single ACAs, we combined all cases in each group (groups 1 and 2) for survival analysis. As shown in Figure 2D-E, the survival of patients with 2 or more ACAs was closer to the survival of patients in group 2 than that of patients in group 1 (Figure 2D: 2 ACAs vs group 1, P < .0001; >2 ACAs vs group 1, P < .0001; 2 ACAs vs group 2, P = .08; >2 ACAs vs group 2, P = .97; Figure 2E: 2 ACAs vs group 1, P < .0001; >2 ACAs vs group 1, P < .0001; 2 ACAs vs group 2, P = .04; >2 ACAs vs group 2, P = .17). The detailed survival curves containing each individual subgroup within groups 1 and 2 was presented in supplemental Figure 1.

Analysis of TKI response and survival according to ACA emerging phase (CP vs AP and BP)

As shown in Table 1, the phases from which ACAs emerged differed according to the specific cytogenetic abnormality. ACAs in group 1 commonly emerged from CP. In contrast, ACAs in group 2 more often emerged during disease progression to either AP or BP. Detailed statistical analysis to compare the difference in the phase of ACA emergence is shown in supplemental Table 5. As the presence of other AP features such as increased blasts may contribute to a poor survival and thus interferes with the study of the roles of ACAs, we stratified the 6 most common ACAs based on their emergence phase: ACAs arising from CP (no other concurrent AP features) and ACAs arising from AP or BP (Table 2).

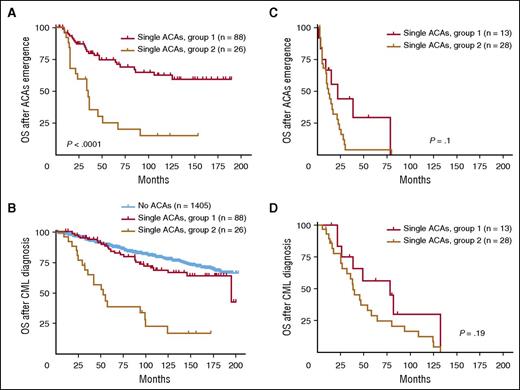

To eliminate the confounding effect from other AP features, we first focused on ACAs emerging from CP and studied their impact on TKI treatment and survival. Similar to the response pattern shown in Table 1, patients in group 1 had a much higher rate of CCyR and MMR than patients in group 2 (Table 2). Consistently, patients in group 1 had a better survival than patients in group 2 (Figure 3A: group 1 vs group 2, P < .0001; Figure 3B: group 1 vs group 2, P < .0001), similar to the pattern shown in Figure 2. When compared with patients with no ACAs, patients in group 1 had no significant survival difference (P = .16), whereas patients in group 2 had a worse survival (P < .0001) (Figure 3B). When cases in group 1 were studied in detail based on specific types of ACAs, all 3 subgroups showed no significant difference when compared with patients with no ACAs (no ACAs vs −Y, P = .66; no ACAs vs trisomy 8, P = .34; no ACAs vs an extra Ph, P = .26) (supplemental Figure 2B).

Survival comparison between 2 groups with single ACAs based on ACA emerging phase. (A-B) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs emerging from CP. (C-D) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs emerging from AP and BP. For panels A and C, OS was calculated from the time of ACA emergence. For panels B and D, OS was calculated from the time of CML diagnosis.

Survival comparison between 2 groups with single ACAs based on ACA emerging phase. (A-B) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs emerging from CP. (C-D) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs emerging from AP and BP. For panels A and C, OS was calculated from the time of ACA emergence. For panels B and D, OS was calculated from the time of CML diagnosis.

We next studied ACAs emerging from AP and BP. Although the number of patients who developed ACAs in AP and BP is relatively small, these patients appeared to have a very poor CCyR and MMR (Table 2). As shown in Figure 3C-D, the survival difference between group 1 and group 2 was diminished (P = .1 in Figure 3C and P = .19 in Figure 3D), presumably because of the presence of other risk factors associated with AP and BP, such as increased blasts, which contributed to the prognosis. These results are consistent with one of our concurrent studies, in which we found that there was no survival difference between BP patients with high- and low-risk ACAs.19 The detailed survival curves including each individual subgroup are shown in supplemental Figure 2C-D.

Analysis of TKI response and survival according to ACA emerging time (at initial CML diagnosis vs during CML course)

As shown in Table 1, the majority of patients developed ACAs during the course of CML treatment, and only a small subset of patients had ACAs at the time of initial CML diagnosis. The exception to this rule was −Y, which was detected at the time of CML diagnosis in 48% of patients. To evaluate whether the timing of ACA emergence may have an impact on treatment response and survival, we divided patients into 2 subsets as follows: patients with ACAs at CML diagnosis and patients with ACAs that emerged during the disease course. As shown in Table 3, in both subsets, patients in group 1 had a better CCyR and MMR than patients in group 2. Within group 1, there was a trend toward a higher CCyR and MMR rate among patients with ACAs that occurred at CML diagnosis when compared with patients with ACAs arising during the CML course.

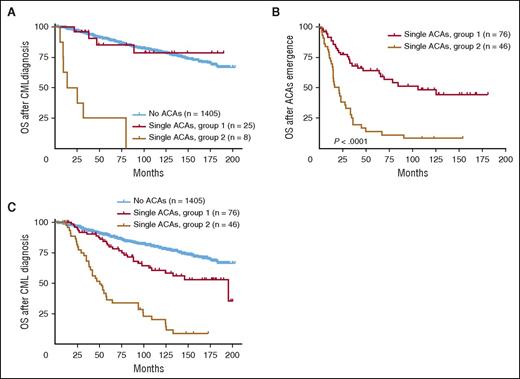

For survival analysis, we first compared the survival of patients with ACAs detected at initial CML diagnosis. As shown in Figure 4A, patients in group 2 showed a worse survival than patients in group 1 (P < .0001). When compared with patients with no ACAs, group 1 patients had a similar survival (P = .77), whereas group 2 patients had a worse survival (P < .0001).

Survival comparison between 2 groups with single ACAs based on ACA emerging time. (A) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs detected at CML diagnosis. (B-C) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs emerging during CML disease. For panels (A) and (C), OS was calculated from the time of CML diagnosis. For panel (B), OS was calculated from the time of ACA emergence.

Survival comparison between 2 groups with single ACAs based on ACA emerging time. (A) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs detected at CML diagnosis. (B-C) Survival comparison in patients with ACAs emerging during CML disease. For panels (A) and (C), OS was calculated from the time of CML diagnosis. For panel (B), OS was calculated from the time of ACA emergence.

For patients who developed ACAs during CML course, survival analysis showed that ACAs in group 1 conferred a better overall prognosis than ACAs in group 2 (Figure 4B, P < .0001; Figure 4C, P < .0001). When compared with patients with no ACAs, both groups showed a worse survival (Figure 4C: group 1 vs no ACAs, P = .001; group 2 vs no ACAs, P < .0001). When cases in group 1 were studied as specific subgroups, patients with −Y showed no difference in survival (P = .18), whereas both trisomy 8 and an extra Ph were associated with a poorer prognosis (no ACAs vs trisomy 8, P = .04; no ACAs vs an extra Ph, P = .02).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed the type, frequency, and role of ACAs in the era of TKI therapy. We focused on CML patients that presented with a single ACA at the initial ACAs emergence. We found that trisomy 8 and an extra Ph were the most common ACAs, followed by −Y, 3q26.2 rearrangements, i(17)(q10), and −7/del(7q). They emerged from different phases (Table 2), and the majority of them emerged during the course of CML treatment (Table 3). Based on their impact on TKI therapy and survival, we stratified these ACAs into 2 main groups: group 1 with a good prognosis includes trisomy 8, −Y, and an extra Ph; and group 2 with a poor prognosis includes i(17), −7/del(7q), and 3q26.2 rearrangements. Consistent with prognosis, patients in group 2 showed a poorer response to TKI treatment than patients in group 1 (Tables 1-3). Other remaining single ACAs, as a group, conferred a similar survival to the good prognostic group (Figure 2), whereas patients with 2 or more ACAs (ie, complex karyotype) had a similar survival to patients in the poor prognostic group (Figure 2).

Besides the comparison between these 2 groups, we also compared their survival with patients with no ACAs. Patients in group 2 consistently showed a worse survival than patients with no ACAs (Figure 2C-D), irrelevant to the emergence phase (Figure 3) and emergence time (Figure 4). When patients in group 1 were compared with patients with no ACAs, −Y consistently showed no survival difference (Figure 2; supplemental Figures 2 and 3). Although trisomy 8 and an extra Ph were associated with a worse OS before stratification (Figure 2C), this association disappeared when we stratified them based on their emergence phase, and only cases with ACAs emerging from CP (no other concurrent AP features) were analyzed. As shown in Figure 3B, patients with trisomy 8 and an extra Ph showed a similar survival as patients with no ACAs. This indicates that the worse survival associated with trisomy 8 and an extra Ph before stratification (Figures 2C and 4C) is attributable to other risk factors associated with AP and/or BP, such as increased blasts, basophilia, or thrombocytopenia. Similarly, when only cases with ACAs at initial CML diagnosis were analyzed, trisomy 8 and an extra Ph had no difference in survival compared with patients with no ACAs (Figure 4A; supplemental Figure 3A).

In the most recent version of European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of CML patients,4 the major route, but not the minor route, cytogenetic changes were included as one of the criteria for AP, largely because the major route changes have been shown to be associated with a poorer prognosis. In this study, trisomy 8 and an extra Ph, although belonging to the group of major route changes, were associated with a relatively good prognosis when they presented as a sole ACA. In contrast, 3q26 rearrangements and −7/del(7q), 2 minor route changes, conferred a poorer prognosis.

It is intriguing that patients with an extra Ph actually had a relatively good prognosis (Figures 2-4). Although one can plausibly speculate that the presence of an extra copy of Ph results in an increased expression of the BCR/ABL1, no study explored the impact of increased BCR/ABL1 levels on response to TKIs and survival. We proposed that the high efficacy of TKIs targeting BCR/ABL1 may diminish the effect of increased BCL/ABL1 expression in cases of clonal evolution with an extra copy of Ph.

Trisomy 8, another major route change, was the most frequent ACA in this study and showed a relatively good prognosis too. In AML and MDS, trisomy 8 is also the most common numerical chromosome aberration and is associated with an intermediate prognosis.2,20 The genetic consequences of trisomy 8, however, remain unknown. Studies have shown that AML with trisomy 8 is heterogeneous at the molecular level,21 and the impact of trisomy 8 is thus likely not related to one particular genetic change. In our study, similar to an extra Ph, trisomy 8 had no negative effect on survival when it emerged from CP as the only feature for disease progression (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 2B). When they emerged at the time of initial CML diagnosis, they also had no negative impact on survival (Figure 4A).

Although previous studies have shown controversial results for the prognostic impact of −Y in CML,12,22 patients with −Y are generally considered to have a good prognosis. In our study, there was no significant difference in OS between patients with −Y and patients with no ACAs (Figures 2-4).

The mechanisms that contribute to poor survival in group 2 are likely related to molecular changes that are induced by the corresponding chromosomal abnormalities. The 3q26.2 locus harbors the EVI1 oncogene, and gene rearrangements involving 3q26.2 induce aberrant EVI1 overexpression.23,24 Aberrant EVI1 expression induces leukomogenesis by modulating various downstream pathways that are involved in hematopoietic differentiation and proliferation.25 In AML, 3q26/inv(3)/t(3;3) confers the worst survival among patients with recurrent genetic abnormalities recognized in the 2008 World Health Organization classification.3,26 In MDS, inv(3)/t(3q)/del(3q) belongs to a poor prognostic subgroup.2 The poor prognosis of patients with i(17)(q10) is likely related to p53 deletion; p53 is a tumor suppressor and plays a critical role in regulating cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis.27 The inactivation of p53 causes genomic instability, neoplastic transformation, and disease progression. Loss of p53 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with AML and MDS.28-30 The specific genetic targets of chromosome 7 deletion are unknown, but studies have demonstrated that −7/del(7q) is associated with adverse prognosis in AML31 and belongs to a poor prognostic subgroup for MDS.2

Finally, it is of interest to mention the gender distribution of CML patients in our study. In the whole cohort (2013 patients), male patients were slightly predominant and accounted for 58%, similar to the percentage reported in the literature. Whereas in cases with ACAs (608 cases), male patients were 63%, and in the high-risk ACA group (Table 1, group 2), male patients increased to 72%.

In conclusion, we stratified ACAs in CML into 2 prognostic groups according to their impact on response to TKI treatment and survival in this study. In contrast to the poor prognostic group, ACAs in the good prognostic group showed no adverse impact on survival when they emerged from CP (in other words, no other concurrent AP features) (Figure 3B) or at the initial CML diagnosis (Figure 4A). This classification system may be useful to guide the clinical management and assess prognosis of CML patients who develop ACAs as a manifestation of clonal evolution.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: W.W. wrote the manuscript; W.W. and S.H. designed the study; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Shimin Hu, Department of Hematopathology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: shu1@mdanderson.org.