Key Points

Hematopoietic populations unrelated to the AML founding clone often expand after induction therapy, resulting in oligoclonal hematopoiesis.

Abstract

There is interest in using leukemia-gene panels and next-generation sequencing to assess acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) response to induction chemotherapy. Studies have shown that patients with AML in morphologic remission may continue to have clonal hematopoiesis with populations closely related to the founding AML clone and that this confers an increased risk of relapse. However, it remains unknown how induction chemotherapy influences the clonal evolution of a patient’s nonleukemic hematopoietic population. Here, we report that 5 of 15 patients with genetic clearance of their founding AML clone after induction chemotherapy had a concomitant expansion of a hematopoietic population unrelated to the initial AML. These populations frequently harbored somatic mutations in genes recurrently mutated in AML or myelodysplastic syndromes and were detectable at very low frequencies at the time of AML diagnosis. These results suggest that nonleukemic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, harboring specific aging-acquired mutations, may have a competitive fitness advantage after induction chemotherapy, expand, and persist long after the completion of chemotherapy. Although the clinical importance of these “rising” clones remains to be determined, it will be important to distinguish them from leukemia-related populations when assessing for molecular responses to induction chemotherapy.

Introduction

Studies have demonstrated that patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) achieving morphologic remission after induction chemotherapy often exhibit oligoclonal hematopoiesis.1-6 In all but one case report,4 these clonal populations were closely related to the initial leukemic clone. There is considerable interest in using next-generation sequencing approaches to assess molecular responses to induction chemotherapy in patients with AML. We recently reported results of a study assessing mutation clearance in 50 patients with AML in morphologic complete remission.7 Clearance of all leukemia-associated mutations was associated with improved overall and event-free survival. Here, we report on a subset of 15 patients for whom exome-sequence data were available for both the diagnostic and a later remission sample. In 5 patients, we identified the rapid expansion of a hematopoietic population unrelated to the initial AML clone.

Study design

Patients

AML samples were collected as part of a single-institution banking protocol (WU HSC #201011766). As previously described,7 the 15 de novo AML patients in this study received an intensive induction chemotherapy regimen, including both cytarabine and an anthracycline, achieving complete morphologic remission with 1 or 2 rounds of chemotherapy (see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood Web site). Bone marrow samples were obtained at diagnosis, after induction therapy, and for 14 of the 15 cases, at long-term follow-up (83-502 days from chemotherapy initiation).

Sequencing

Enhanced exome sequencing (EES) was performed as previously described.7 AmpliSeq sequencing was used to validate 86 somatic mutations identified by EES (supplemental Table 2) as previously described.7 Variant allele frequencies (VAFs) were compared between samples with evidence of a rising clone and 15 to 16 control samples not expected to carry the variant of interest. Significance was determined using Fisher’s exact test.

Droplet digital PCR

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) was performed as previously described.8-10 VAFs >1% were calculated assuming a Poisson distribution of genomes among droplets.

Isolation of leukemic blasts

Cryopreserved cells were thawed as previously described.11 The CD34+ leukemic population (CD45dim/SSClow/CD34+/7-AAD−) was sorted using a modified Beckman Coulter MoFlo. Genomic DNA was isolated with the QIAmp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands).

Results and discussion

We previously reported the genetic analysis of paired diagnostic and remission bone marrow samples from 50 adult patients with de novo AML achieving morphologic complete remission following induction therapy.7 In the current study, we assessed the effect of intensive chemotherapy on hematopoietic populations unrelated to the leukemic clone. To clearly distinguish these nonleukemic clones from persistent leukemia-related populations, we limited our analysis to a subset of 15 cases (supplemental Table 1) in which (1) unbiased (EES) data were available and (2) the patients achieved molecular remission following induction therapy with all AML-associated mutations at a VAF ≤2.5%.

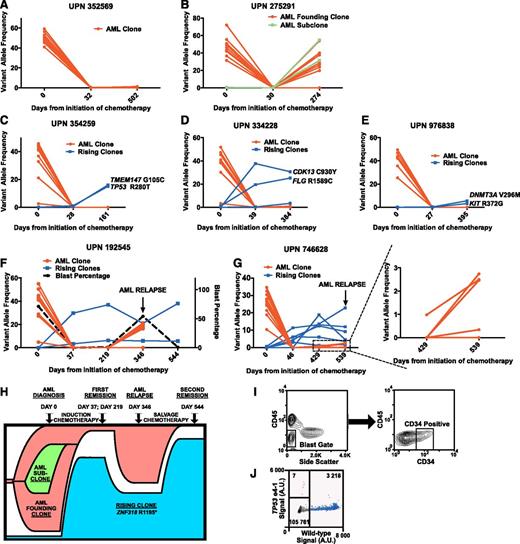

We observed 3 patterns of hematopoiesis. In 4 cases, we detected no evidence of clonal hematopoiesis after induction therapy with no somatic mutations at a VAF ≥2.5% (Figure 1A). In 6 cases, 1 or more mutations identified in the diagnostic AML sample reappeared in the long-term follow-up sample, representing relapse from the AML founding clone or one of its subclones (Figure 1B). Interestingly, 5 cases exhibited a novel pattern of hematopoiesis. Somatic variants not detected in the AML diagnostic sample were detected and validated in 1 or more remission samples with no evidence of any AML-associated mutations (Table 1 and Figure 1C-G), suggesting that a hematopoietic population unrelated to the initial AML (termed a “rising” clone) expanded following chemotherapy. In each case, the rising clone remained detectable at stable (or expanding) levels throughout the observation period (161-544 days). We used AmpliSeq sequencing to validate putative mutations identified in the AML clone or rising clones (supplemental Tables 2 and 3). One or more mutations associated with a rising clone were validated in 5 cases (Table 1 and supplemental Table 4). These variants were enriched for mutations in genes implicated in AML and MDS pathogenesis including TP53 (2 cases), TET2, DNMT3A, and ASXL1 (Table 1).12,13 Patients with evidence of a rising clone after induction therapy had clinical and hematologic characteristics similar to patients lacking such evidence (supplemental Figure 1).

The expansion of nonleukemic hematopoietic clonal populations is frequently observed following induction therapy for de novo AML patients. Somatic mutations were identified at the time of diagnosis, after induction chemotherapy, and at long-term follow-up using enhanced exome sequencing. Mutations present in the AML founding clone or subclone(s) are highlighted in red. Mutations present in rising clones are highlighted in blue. (A) Representative data from a patient with no evidence of clonal hematopoiesis after cytoreductive therapy. (B) Representative data from a patient with recurrence of his AML after chemotherapy with the concomitant expansion of an AML subclone harboring additional somatic mutations (shown in green). (C-G) All 5 patients with validated genetic evidence showing expansion of a nonleukemic hematopoietic clone after chemotherapy. (H) Proposed model of clonal evolution under the influence of cytoreductive chemotherapy in UPN 192545. (I) Sorting strategy used to isolate relapsed CD34+CD45dimSSClow leukemic blasts in UPN 746628. (J) ddPCR plot assessing the presence of the TP53 e4-1 allele in the leukemic blast population of UPN 746628. Droplets containing only the TP53 e4-1 allele are highlighted in orange. droplets containing the wild-type allele (with or without the TP53 e4-1 allele) are highlighted in blue, and empty droplets are gray. The number of droplets in each gate is indicated. A.U., arbitrary units.

The expansion of nonleukemic hematopoietic clonal populations is frequently observed following induction therapy for de novo AML patients. Somatic mutations were identified at the time of diagnosis, after induction chemotherapy, and at long-term follow-up using enhanced exome sequencing. Mutations present in the AML founding clone or subclone(s) are highlighted in red. Mutations present in rising clones are highlighted in blue. (A) Representative data from a patient with no evidence of clonal hematopoiesis after cytoreductive therapy. (B) Representative data from a patient with recurrence of his AML after chemotherapy with the concomitant expansion of an AML subclone harboring additional somatic mutations (shown in green). (C-G) All 5 patients with validated genetic evidence showing expansion of a nonleukemic hematopoietic clone after chemotherapy. (H) Proposed model of clonal evolution under the influence of cytoreductive chemotherapy in UPN 192545. (I) Sorting strategy used to isolate relapsed CD34+CD45dimSSClow leukemic blasts in UPN 746628. (J) ddPCR plot assessing the presence of the TP53 e4-1 allele in the leukemic blast population of UPN 746628. Droplets containing only the TP53 e4-1 allele are highlighted in orange. droplets containing the wild-type allele (with or without the TP53 e4-1 allele) are highlighted in blue, and empty droplets are gray. The number of droplets in each gate is indicated. A.U., arbitrary units.

Because rising clones appeared rapidly following induction therapy, we predicted that mutations harbored by them were present in rare cells before therapy. In UPN 334228, EES with AmpliSeq sequencing identified the rising clone variant FLG R1589C in the diagnostic sample at a VAF of 0.46%, significantly higher than in control samples (VAF: 0.07% ± 0.04%; P < .0001). For the other 4 patients, we designed ddPCR assays against one or more of the mutations present in the rising clones. All were detectable in the diagnostic bone marrow samples at VAFs from 0.007% to 0.75% (Table 1 and supplemental Figure 2), demonstrating that some (and perhaps most) of the rising clone mutations were present in rare cells prior to treatment.

Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential in healthy adults is typically identified in elderly individuals, and the clonal population often remains stable (or expands slowly) over multiple years.14-16 In contrast, patients with a rising clone following induction therapy were relatively younger and exhibited a rapid expansion of their clones (∼30- to 150-fold within 1-2 months of chemotherapy initiation). These observations, along with the specificity of mutations harbored by these clones, suggest that AML cytoreductive chemotherapy confers a strong competitive advantage to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) harboring specific “fitness” mutations. This is consistent with previous reports that cytotoxic therapy provides a strong selection pressure on both leukemic and nonleukemic hematopoietic populations.10,17-19 Whether the resulting oligoclonal hematopoiesis reflects a contraction of the normal HSPC pool, an active and selective expansion of the rising clone, or a combination of both remains unclear.

Two of the five patients with rising clones relapsed. EES was performed on both patients’ relapsed bone marrow samples. In UPN 192545 (54% blasts), the majority of the original leukemia-associated mutations were reidentified at VAFs from 16% to 21% with 3 subclonal mutations no longer detectable (Figure 1F and supplemental Table 5). Interestingly, the two rising clone mutations in this patient (ZNF318 R1195* and TET2 Q1828*) persisted at VAFs of 20.9% and 5.9% respectively (Figure 1F,H). After salvage therapy, UPN 192545 re-achieved morphologic remission, with the rising clone harboring ZNF318 R1195* further expanding, eventually comprising the majority (∼76%) of hematopoietic cells (Figure 1F,H).

In UPN 746628 (9% blasts), both rising clone and some leukemia-associated variants were present at low levels, making it difficult to determine the origin of the AML relapse (Figure 1G and supplemental Table 5). We sorted leukemic cells (CD45dim/SSClow/CD34+; Figure 1I) from cryopreserved peripheral blood cells banked at relapse and assessed for the rising variant TP53 e4-1 with ddPCR. The VAF for TP53 e4-1 was only 0.2% (Figure 1J), indicating that the relapsed AML originated not from the rising clone but more likely from the founding AML clone.

Because both relapses evolved from the initial AML clone and not from rising clones, the clinical consequences of oligoclonal hematopoiesis arising from nonleukemic HSPCs following induction chemotherapy are unclear. Interestingly, studies have reported cases of AML relapsing with a karyotype incompatible with the AML present at diagnosis, suggesting that, in some cases, relapsed AML may arise from a hematopoietic cell unrelated to the initial AML.20-24 Given the sensitivity limitations of next-generation sequencing and the difficulty in distinguishing rising clones from coexisting persistent leukemia-related populations, this study likely underestimates the genetic complexity of patients with AML after induction therapy. Additional patients and longer follow-up are needed to define the extent and prognostic implications of nonleukemic clonal expansion following AML therapy. It will also be important to distinguish rising clones from persistence of leukemia-related populations when assessing for molecular responses to induction chemotherapy.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Amy Schmidt and Dr Brandon McKethan (Bio-Rad) for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant PO1 CA101937 (D.C.L. and T.J.L.), National Human Genome Research Institute grant U54 HG003079 (R.K.W.), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants T32 HL007088 (T.N.W.) and K12 HL087107 (T.N.W.). Technical support was provided by the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center Tissue Procurement Core and the High Speed Cell Sorting Core at Washington University School of Medicine, which are supported by National Cancer Institute grant P30CA91842.

Authorship

Contribution: T.N.W. designed and performed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; C.A.M., A.P., R.D., T.L., R.S.F., E.R.M., and R.K.W. contributed to the generation and analysis of EES and AmpliSeq sequencing data; N.M.H., T.J.L., S.E.H., J.M.K., and P.W. collected and processed clinical data and tissue samples; J.M.K., J.S.W., J.F.D., M.J.W., T.A.G., and T.J.L. contributed to data analysis; and D.C.L. supervised all of the research and edited the manuscript, which was approved by all coauthors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Daniel C. Link, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S Euclid Ave, Campus Box 8007, Saint Louis, MO 63110; e-mail: dlink@dom.wustl.edu.