Key Points

TNF-α produced during aGVHD is a strong and selective activator of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs.

In vitro TNF-α priming enhances CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Treg proliferation and their ability to protect from GVHD.

Abstract

CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been shown to effectively prevent graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) when adoptively transferred in murine models of hematopoietic cell transplantation and in phase 1/2 clinical trials. Critical limitations to Treg clinical application are the paucity of cells and limited knowledge of the mechanisms of in vivo function. We hypothesized that inflammatory conditions in GVHD modify Treg characteristics and activity. We found that peripheral blood of recipient animals during acute GVHD (aGVHD) induces Treg activation and enhances their function. The serum contains high levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) that selectively activates Tregs without impacting CD4+FoxP3− T cells. TNF-α priming induces Treg in vivo proliferation, whereas it limits the ability of CD4 and CD8 conventional T cells (Tcons) to proliferate and induce GVHD. TNF-α–primed Tregs prolong animal survival as compared with unprimed Tregs when used at an unfavorable Treg:Tcon ratio, demonstrating enhanced in vivo efficacy of TNF-α–primed Tregs. Because TNF-α is produced by several immune cells during inflammation, our work elucidates aspects of the physiologic mechanisms of Treg function. Furthermore, TNF-α priming of Tregs provides a new tool to optimize Treg cellular therapies for GVHD prevention and treatment.

Introduction

CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) are a subset of T lymphocytes that can suppress proliferation and function of effector immune cells.1 Preclinical and clinical studies have demonstrated that Treg and CD4+ and CD8+ conventional T cell (Tcons) adoptive transfer can effectively prevent graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD), a life-threatening disease that may follow hematopoietic cell transplantation, while maintaining graft-versus-tumor effects.2-6 However, Tregs are rare cells representing only 5% to 10% of CD4+ T cells in the peripheral blood (PB). Because of their paucity and challenges in purification there is great interest in Treg expansion and enhancement of function.7,8 We and others have attempted to increase the Treg number and Treg:Tcon ratio in vivo.2,9-14 An alternative approach to Treg expansion is to enhance their function. In this study, we tested the effects of the acute GVHD (aGVHD) inflammatory environment on Treg function. Tregs exposed to serum from animals with aGVHD increase the expression of activation molecules and enhance functional capabilities. We focused on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a cytokine produced by different tissues during inflammation. Even though TNF-α has been widely recognized for its proinflammatory role in GVHD, it could be used to expand human Tregs and ameliorate their suppressive activity in vitro.15 We found that TNF-α exposure selectively activates Tregs and enhances their function, providing new insights into Treg mechanisms of action and raising the possibility of a further improvement in Treg-based cellular therapies.

Study design

In vitro cell priming and cell culture

Tregs or Tcons were cultured with interleukin-2 (IL-2) 50 IU/mL (standard conditions) for 48 hours or unless specified in the text. For priming with irradiated (30 Gy) PB from aGVHD-affected mice, PB of allogeneic transplanted mice that received donor Tcons at day +6 was collected after transplantation, irradiated, and added to the cells. For priming with TNF-α and other cytokines, different cytokine concentrations were added as indicated. After priming, cells were washed twice and used as indicated.

Transplantation studies

For a description of mice, cell isolation, and Treg depletion, see supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site. Mice were transplanted as previously described,16 briefly lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were rescued with 5 × 106 T-cell–depleted bone marrow (TCD-BM) cells from C57BL/6 mice. GVHD was induced with 0.75-1 × 106 C57BL/6-derived Tcons at day 0. C57BL/6 Tregs were injected at different time points and doses as indicated.

Results and discussion

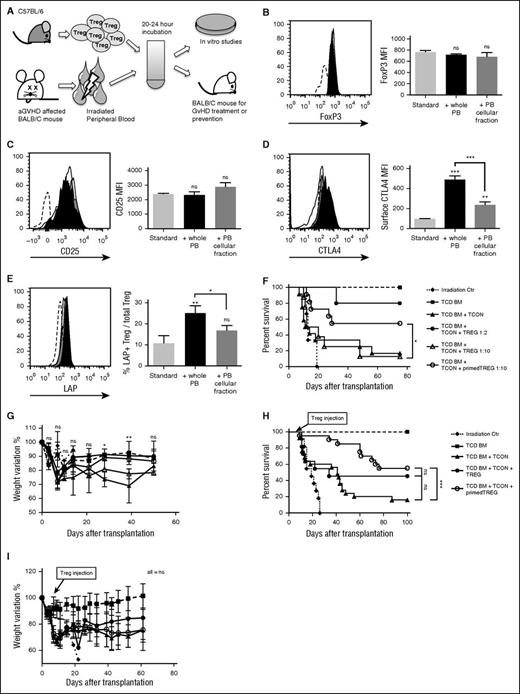

To understand the role of Tregs during aGVHD, we incubated freshly isolated donor-type Tregs with irradiated PB from aGVHD-affected mice (Figure 1A). We detected only a few donor T cells with no residual host-type white blood cells in the PB at the time of harvesting (day +5 or +6, data not shown). After a short in vitro culture (20 hours), Tregs maintained high FoxP3 and CD25 expression (Figure 1B-C) and had higher expression of molecules relevant for their suppressive activity such as CTLA4 (P < .001; Figure 1D) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) (P = .008; Figure 1E). Removing the serum from the aGVHD blood during Treg priming resulted in partial loss of CTLA4 (P < .001) and TGF-β (P = .03) upregulation, demonstrating that components in the serum were required for effective Treg activation (Figure 1D-E).

Exposure to PB of GVHD-affected animals induces Treg activation and enhances Treg in vivo function. (A) Experimental scheme. PB from BALB/c mice affected by aGVHD was harvested at day +6 after hematopoietic cell transplantation and incubated with allogeneic Tregs obtained from healthy C57BL/6 animals. After 20 to 24 hours of culture, Tregs were washed and used for in vitro or in vivo experiments. (B-E) Graphs that report expression in gated CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs of intracellular FoxP3 (B), surface CD25 (C), surface CTLA4 (D), and TGF-β (measured through the surface expression of TGF-β LAP) (E) are shown. Unprimed Tregs (cultured with standard culture conditions only) are shown in white, Tregs primed with irradiated aGVHD PB in black, and Tregs primed with only the cellular fraction of irradiated aGVHD PB in gray. Sample staining histograms are also reported where unprimed Tregs stained with isotype control antibody (dashed line), unprimed Tregs (white), PB-primed Tregs (black), and PB cellular fraction-primed Tregs (gray) are shown. Data are representative of 1 of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis has been performed with 2-tailed Student t test. (F-G) C57BL/6 allogeneic aGVHD PB-primed Tregs were injected in a mouse model of GVHD, together with TCD-BM and Tcons from C57BL/6 allogeneic donor mice at day 0 into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients. Survival (F) and percentage of weight recovery (G) after transplantation of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,

), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons ( ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 ( ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ) are reported. Shown data are the results of 2 pooled independent experiments. (H-I) C57BL/6 allogeneic aGVHD PB-primed Tregs were injected in a mouse model of GVHD 6 to 7 days after injection of C57BL/6 allogeneic TCD-BM and luc+ Tcons into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients that showed clear signs and symptoms of aGVHD with a minimum GVHD score of 4, and had Tcon proliferation in vivo analyzed by BLI. The Treg:Tcon ratio used was 1:2. Survival (H) and percentage of weight recovery (I) after transplantation are reported of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,

) are reported. Shown data are the results of 2 pooled independent experiments. (H-I) C57BL/6 allogeneic aGVHD PB-primed Tregs were injected in a mouse model of GVHD 6 to 7 days after injection of C57BL/6 allogeneic TCD-BM and luc+ Tcons into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients that showed clear signs and symptoms of aGVHD with a minimum GVHD score of 4, and had Tcon proliferation in vivo analyzed by BLI. The Treg:Tcon ratio used was 1:2. Survival (H) and percentage of weight recovery (I) after transplantation are reported of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,

), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons ( ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs ( ), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs (

), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs ( ). Reported data are the result of 4 pooled independent experiments. In survival experiments statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas weight variations were assessed by 2-way ANOVA test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; BLI, bioluminescent imaging; LAP, latency associated peptide; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

). Reported data are the result of 4 pooled independent experiments. In survival experiments statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas weight variations were assessed by 2-way ANOVA test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; BLI, bioluminescent imaging; LAP, latency associated peptide; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

Exposure to PB of GVHD-affected animals induces Treg activation and enhances Treg in vivo function. (A) Experimental scheme. PB from BALB/c mice affected by aGVHD was harvested at day +6 after hematopoietic cell transplantation and incubated with allogeneic Tregs obtained from healthy C57BL/6 animals. After 20 to 24 hours of culture, Tregs were washed and used for in vitro or in vivo experiments. (B-E) Graphs that report expression in gated CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs of intracellular FoxP3 (B), surface CD25 (C), surface CTLA4 (D), and TGF-β (measured through the surface expression of TGF-β LAP) (E) are shown. Unprimed Tregs (cultured with standard culture conditions only) are shown in white, Tregs primed with irradiated aGVHD PB in black, and Tregs primed with only the cellular fraction of irradiated aGVHD PB in gray. Sample staining histograms are also reported where unprimed Tregs stained with isotype control antibody (dashed line), unprimed Tregs (white), PB-primed Tregs (black), and PB cellular fraction-primed Tregs (gray) are shown. Data are representative of 1 of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis has been performed with 2-tailed Student t test. (F-G) C57BL/6 allogeneic aGVHD PB-primed Tregs were injected in a mouse model of GVHD, together with TCD-BM and Tcons from C57BL/6 allogeneic donor mice at day 0 into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients. Survival (F) and percentage of weight recovery (G) after transplantation of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,

), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons ( ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 ( ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ) are reported. Shown data are the results of 2 pooled independent experiments. (H-I) C57BL/6 allogeneic aGVHD PB-primed Tregs were injected in a mouse model of GVHD 6 to 7 days after injection of C57BL/6 allogeneic TCD-BM and luc+ Tcons into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients that showed clear signs and symptoms of aGVHD with a minimum GVHD score of 4, and had Tcon proliferation in vivo analyzed by BLI. The Treg:Tcon ratio used was 1:2. Survival (H) and percentage of weight recovery (I) after transplantation are reported of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,

) are reported. Shown data are the results of 2 pooled independent experiments. (H-I) C57BL/6 allogeneic aGVHD PB-primed Tregs were injected in a mouse model of GVHD 6 to 7 days after injection of C57BL/6 allogeneic TCD-BM and luc+ Tcons into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients that showed clear signs and symptoms of aGVHD with a minimum GVHD score of 4, and had Tcon proliferation in vivo analyzed by BLI. The Treg:Tcon ratio used was 1:2. Survival (H) and percentage of weight recovery (I) after transplantation are reported of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,

), mice that received TCD-BM (dashed line,  ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons ( ), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs (

), mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs ( ), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs (

), and mice that received TCD-BM + Tcons + aGVHD PB-primed Tregs ( ). Reported data are the result of 4 pooled independent experiments. In survival experiments statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas weight variations were assessed by 2-way ANOVA test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; BLI, bioluminescent imaging; LAP, latency associated peptide; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

). Reported data are the result of 4 pooled independent experiments. In survival experiments statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas weight variations were assessed by 2-way ANOVA test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; BLI, bioluminescent imaging; LAP, latency associated peptide; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; ns, not significant.

We further tested if PB-Treg priming modified the ability of Tregs to suppress GVHD in vivo. Allogeneic TCD-BM was transplanted into BALB/c recipients, followed by C57BL/6 Tcons and primed or unprimed Tregs at day 0 of transplantation. Although mice that received a 1:2 unprimed Treg:Tcon ratio had improved survival (P = .02), as expected4,16 the 1:10 unprimed Treg:Tcon ratio was ineffective in ameliorating GVHD (P > .05). Importantly, at this 1:10 Treg:Tcon ratio, animals that received primed Tregs resulted in increased survival (P = .03; Figure 1F) and improved mouse weight profile (day +28, P < .05; day +39, P < .01; Figure 1G). We also investigated the effect of Treg priming for aGVHD treatment using luc+ Tcons for inducing GVHD, and transferring primed or unprimed Tregs at the 1:2 Treg:Tcon ratio at day +6 or +7 after transplantation in mice that showed Tcon in vivo proliferation measured by BLI (data not shown), and clinical signs and symptoms of GVHD (GVHD score ≥4). Although unprimed Tregs did not improve mouse survival, PB-primed Tregs improved survival by delaying GVHD lethality (P = .0007; Figure 1H). No differences were observed in weight profile because weight loss had already occurred at the time of Treg treatment (P > .05; Figure 1I). These results demonstrate that irradiated aGVHD PB induces Treg activation resulting in enhanced Treg in vivo function. Therefore, Tregs respond to the inflammatory conditions associated with aGVHD by acquiring a more suppressive phenotype.

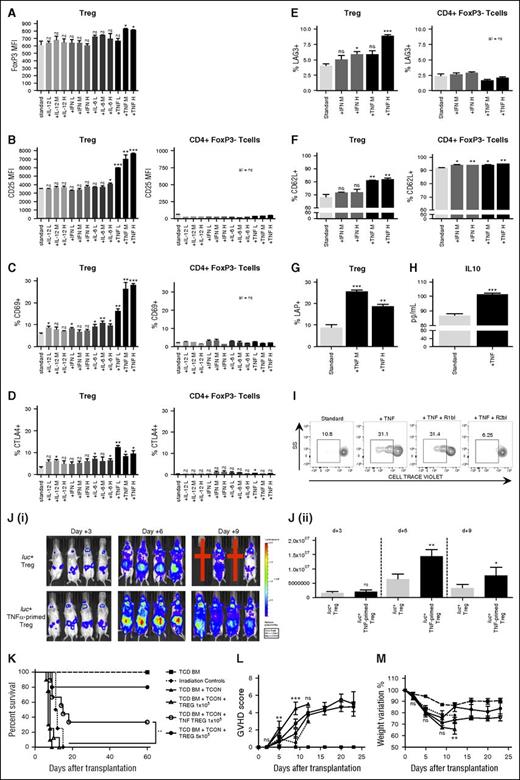

In our aGVHD mouse model, high levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α were detectable (data not shown). Therefore, we tested the ability of such circulating cytokines to activate Tregs by culturing CD4+ T cells with cytokines at varying concentrations. Analyzing the TNF-α–priming effect on Tregs, we found that it intensified FoxP3 expression (P = .02), increased surface expression of activation markers such as CD25 (P < .0001), CD69 (P < .0001), CTLA4 (P = .02), and LAG3 (P = .0002), enhanced the expression of CD62L (P = .0046), a homing marker required for in vivo function (Figure 2A-F; supplemental Figure 1A),17 and induced greater production of suppressive cytokines such as TGF-β (P = .003) and IL-10 (P = .0008; Figure 2G-H). Using identical culture conditions, CD4+FoxP3− T cells did not show activation (Figure 2B-F) demonstrating that TNF-α selectively activates Tregs when incubated with CD4+ T cells.

TNF-α priming induces Treg activation, promote their proliferation, and enhances their ability to suppress GVHD. (A-G) Tcons were primed for 48 hours with standard culture conditions (white bars) or with the addition of interferon-γ (light gray bars), IL-6 (medium gray bars), IL-12 (dark gray bars), or TNF-α (black bars) at different concentrations (L = low concentration = 1 ng/mL, M = medium concentration = 10 ng/mL, and H = high concentration = 100 ng/mL). TNF-α priming resulted in increased Treg expression of FoxP3 (A), CD25 (B), CD69 (C), surface CTLA4 (D), LAG3 (E), CD62L (F), and LAP (G). Data have been collected after gating live Tcon cells for CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs and CD4+FoxP3− T cells. Data are representative of 1 of 5 experiments. (H) IL-10 concentration was measured in supernatants of cultured Tcons and resulted higher when cells were incubated with TNF-α (black) than with standard conditions (white). Data are representative of 1 of 2 experiments. (I) Sorted unprimed Tregs, TNF-α–primed Tregs, TNF-α–primed Tregs in the presence of TNFRI blocking antibody, and TNF-α–primed Tregs in the presence of TNFRII blocking antibody were stained with CellTrace Violet proliferation dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated with irradiated allogeneic splenocytes in the presence of IL-2. Sample gating analysis showing CellTrace Violet dye dilution due to cell proliferation is reported for all the different conditions. TNF-α priming increased the Treg proliferative response to the allogeneic stimulus, TNFRI-blocking antibody did not interfere with such response, whereas TNFRII abrogated it. Data are representative of 1 of 3 consecutive experiments. (J) C57BL/6 luc+ TNF-α–primed Tregs were washed and injected into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients that also received allogeneic C57BL/6 TCD-BM and Tcons at the Treg:Tcon 1:10 ratio. BLI sample images are shown (i). Red crosses represent mice that did not survive the experiment. BLI revealed increased in vivo proliferation of luc+ TNF-α–primed Tregs (black bars) at day +6 and at day +9 after transplantation in comparison with unprimed Tregs (white bars) (ii). Data are representative of 1 of 3 experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with the 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (K-M) C57BL/6 allogeneic TNF-α–primed Tregs were injected together with TCD-BM and Tcons (1 × 106) from C57BL/6 allogeneic donor mice at day 0 into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients. Survival (K), GVHD score (L), and percentage of weight recovery (M) after transplantation of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,  ), TCD-BM (dashed line,

), TCD-BM (dashed line,  ), TCD-BM + Tcons (

), TCD-BM + Tcons ( ), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 (

), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 ( ), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ), and TCD-BM + Tcons + TNF-α–primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), and TCD-BM + Tcons + TNF-α–primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ) are shown. Data are the result of 2 pooled experiments. In survival experiments, statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas in GVHD score and weight variation experiments, the 2-way ANOVA test was used. *P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ns, not significant; SS, side scatter; TNFRI, TNF receptor I; TNFRII, TNR receptor II.

) are shown. Data are the result of 2 pooled experiments. In survival experiments, statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas in GVHD score and weight variation experiments, the 2-way ANOVA test was used. *P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ns, not significant; SS, side scatter; TNFRI, TNF receptor I; TNFRII, TNR receptor II.

TNF-α priming induces Treg activation, promote their proliferation, and enhances their ability to suppress GVHD. (A-G) Tcons were primed for 48 hours with standard culture conditions (white bars) or with the addition of interferon-γ (light gray bars), IL-6 (medium gray bars), IL-12 (dark gray bars), or TNF-α (black bars) at different concentrations (L = low concentration = 1 ng/mL, M = medium concentration = 10 ng/mL, and H = high concentration = 100 ng/mL). TNF-α priming resulted in increased Treg expression of FoxP3 (A), CD25 (B), CD69 (C), surface CTLA4 (D), LAG3 (E), CD62L (F), and LAP (G). Data have been collected after gating live Tcon cells for CD4+FoxP3+ Tregs and CD4+FoxP3− T cells. Data are representative of 1 of 5 experiments. (H) IL-10 concentration was measured in supernatants of cultured Tcons and resulted higher when cells were incubated with TNF-α (black) than with standard conditions (white). Data are representative of 1 of 2 experiments. (I) Sorted unprimed Tregs, TNF-α–primed Tregs, TNF-α–primed Tregs in the presence of TNFRI blocking antibody, and TNF-α–primed Tregs in the presence of TNFRII blocking antibody were stained with CellTrace Violet proliferation dye (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated with irradiated allogeneic splenocytes in the presence of IL-2. Sample gating analysis showing CellTrace Violet dye dilution due to cell proliferation is reported for all the different conditions. TNF-α priming increased the Treg proliferative response to the allogeneic stimulus, TNFRI-blocking antibody did not interfere with such response, whereas TNFRII abrogated it. Data are representative of 1 of 3 consecutive experiments. (J) C57BL/6 luc+ TNF-α–primed Tregs were washed and injected into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients that also received allogeneic C57BL/6 TCD-BM and Tcons at the Treg:Tcon 1:10 ratio. BLI sample images are shown (i). Red crosses represent mice that did not survive the experiment. BLI revealed increased in vivo proliferation of luc+ TNF-α–primed Tregs (black bars) at day +6 and at day +9 after transplantation in comparison with unprimed Tregs (white bars) (ii). Data are representative of 1 of 3 experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with the 2-tailed Student t test. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. (K-M) C57BL/6 allogeneic TNF-α–primed Tregs were injected together with TCD-BM and Tcons (1 × 106) from C57BL/6 allogeneic donor mice at day 0 into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients. Survival (K), GVHD score (L), and percentage of weight recovery (M) after transplantation of mice that received only lethal irradiation (dotted line,  ), TCD-BM (dashed line,

), TCD-BM (dashed line,  ), TCD-BM + Tcons (

), TCD-BM + Tcons ( ), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 (

), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:2 ( ), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), TCD-BM + Tcons + unprimed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ), and TCD-BM + Tcons + TNF-α–primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 (

), and TCD-BM + Tcons + TNF-α–primed Tregs at the Treg:Tcon ratio of 1:10 ( ) are shown. Data are the result of 2 pooled experiments. In survival experiments, statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas in GVHD score and weight variation experiments, the 2-way ANOVA test was used. *P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ns, not significant; SS, side scatter; TNFRI, TNF receptor I; TNFRII, TNR receptor II.

) are shown. Data are the result of 2 pooled experiments. In survival experiments, statistical analysis has been performed with the Log-rank test, whereas in GVHD score and weight variation experiments, the 2-way ANOVA test was used. *P < .01; ***P < .001. ANOVA, analysis of variance; ns, not significant; SS, side scatter; TNFRI, TNF receptor I; TNFRII, TNR receptor II.

TNF-α priming also modifies Treg proliferative response as demonstrated by increased Ki67 expression (supplemental Figure 1B) and their ability to proliferate in vitro against an allogeneic stimulus in a TNF receptor II-dependent manner (P = .04; Figure 2I), and in vivo when donor luc+ TNF-α–primed Tregs where injected in a GVHD model at 1:10 Treg:Tcon ratio (day +6, P = .001; day +9, P = .04; Figure 2J). Conversely, we found that TNF-α–primed Tcons had reduced in vivo proliferation over time in comparison with unprimed Tcons (day +7, P = .01; supplemental Figure 2A).

To study the TNF-α priming effect on Treg-mediated protection from GVHD donor TNF-α–primed or unprimed Tregs at 1:2 and 1:10, Treg:Tcon ratios were infused into allogeneic transplanted BALB/c mice on day 0. As expected, Tregs at the 1:2 Treg:Tcon ratio effectively prolonged mouse survival (P = .0003), whereas unprimed Tregs at the 1:10 Treg:Tcon ratio did not have any impact (P > .05). Conversely, TNF-α–primed Tregs at the 1:10 ratio prolonged mouse survival (P = .002), improved GVHD score (day +5, P < .01; day +9, P < .001), and resulted in weight gain (P < .01; Figure 2K-M). Thus, TNF-α priming activates Tregs and induces their proliferation resulting in improved in vivo function. On the other hand, TNF-α–primed Tcons induced milder GVHD than unprimed Tcons leading to prolonged mouse survival (P = .02) and improvement in GVHD score (day +10, P < .01; day +17, P < .001; supplemental Figure 2B-C). The beneficial effect of TNF-α priming was lost in Treg-depleted Tcons, suggesting that TNF-α–priming effects on Tcons are mediated by TNF-α–induced Treg activation.

We further injected A20 leukemia cells to induce tumor engraftment in allogeneic transplanted BALB/c recipients that also received Tcons and TNF-α–primed Tregs. TNF-α–primed Tregs did not restore leukemia expansion but prolonged mouse survival (P = .03; supplemental Figure 3), thus maintaining Tcon-mediated graft-versus-tumor effects.

Recently, several authors reported contradictory results on TNF-α–mediated effects on Treg function giving rise to a debate on TNF-α effects on human Tregs.15,18-22 Our models offer a unique perspective, demonstrating that brief TNF-α priming coupled with IL-2 stimulation can be used to improve cellular therapy with highly purified (FoxP3 ≥95%) mouse-derived Tregs in GVHD, and/or to minimize Tcons morbidity and lethality. Moreover, anti–TNF-α treatments are employed in GVHD and autoimmune diseases.23,24 Our data suggest that they may negatively impact on Treg function in vivo, possibly explaining the variability in clinical responses.

We believe that our work elucidates aspects of the complex interplay between Tcons, Tregs, and inflammatory conditions during GVHD. TNF-α priming of Tregs through its selective and potent effect allows for the use of a reduced cell number for GVHD prevention and treatment.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Stanford Shared Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Facility, and the Stanford Center for Innovation in In-Vivo Imaging (SCI3) for providing facilities for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis and in vivo imaging.

This work was supported by Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (A.P.), Società Italiana di Ematologia Sperimentale and Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie-Linfomi e Mieloma (A.P.), the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (A.P.), and Program Project grants from the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (CA49605, HL075462, and R01 HL114591) (R.S.N.).

Authorship

Contribution: A.P. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; W.S. performed research, analyzed data, and reviewed the manuscript; C.M., J.B., H.N., M.A., Y.P., and D.S. performed research and reviewed the manuscript; E.M. reviewed the manuscript and provided overall guidance; and R.S.N. helped write the manuscript and provided overall guidance.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert S. Negrin, Stanford University School of Medicine, Center for Clinical Sciences Research Building, Room 2205, 269 Campus Dr, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail: negrs@stanford.edu; and Antonio Pierini, Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Program, Division of Hematology and Clinical Immunology, Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy; e-mail: antonio.pierini@unipg.it.