Abstract

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is a distinct myeloproliferative neoplasm with a high prevalence (>80%) of mutations in the colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R). These mutations activate the receptor, leading to the proliferation of neutrophils that are a hallmark of CNL. Recently, the World Health Organization guidelines have been updated to include CSF3R mutations as part of the diagnostic criteria for CNL. Because of the high prevalence of CSF3R mutations in CNL, it is tempting to think of this disease as being solely driven by this genetic lesion. However, recent additional genomic characterization demonstrates that CNL has much in common with other chronic myeloid malignancies at the genetic level, such as the clinically related diagnosis atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. These commonalities include mutations in SETBP1, spliceosome proteins (SRSF2, U2AF1), and epigenetic modifiers (TET2, ASXL1). Some of these same mutations also have been characterized as frequent events in clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential, suggesting a more complex disease evolution than was previously understood and raising the possibility that an age-related clonal process of preleukemic cells could precede the development of CNL. The order of acquisition of CSF3R mutations relative to mutations in SETBP1, epigenetic modifiers, or the spliceosome has been determined only in isolated case reports; thus, further work is needed to understand the impact of mutation chronology on the clonal evolution and progression of CNL. Understanding the complete landscape and chronology of genomic events in CNL will help in the development of improved therapeutic strategies for this patient population.

Introduction

The Philadelphia chromosome 1,1,2 which results in the BCR-ABL1 fusion oncoprotein3-5 was identified in the vast majority of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients. This has led to both improved diagnosis and highly effective therapeutics for patients with CML.6 For those patients with BCR-ABL1-negative myeloid leukemia characterized by high levels of neutrophils or neutrophil precursors, our understanding of the molecular basis of the disease and treatment strategies have lagged far behind. One such BCR-ABL1-negative myeloid leukemia is chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL), a rare disease entity that was officially recognized as part of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors in 2001.7

For CNL or the related disorder atypical CML (aCML), diagnosis and treatment are challenging. CNL is characterized by more mature neutrophils and bands, whereas in aCML, there is an increase in both neutrophils and neutrophil precursors. Major criteria for CNL include >80% of the peripheral white blood cells being segmented neutrophils or bands with a total white blood cell count of ≥25 × 109/L and <10% of the white blood cells being immature granulocytic forms.8 Criteria for CNL also include hypercellularity of the marrow with <5% myeloblasts among nucleated cells, as well as normal neutrophil maturation with no granulocytic dysplasia.8 In contrast, aCML involves granulocytic dysplasia with at least 10% of peripheral white cells consisting of immature granulocytic forms (promyelocytes, myelocytes, and metamyelocytes).8 One of the challenges in the diagnosis of CNL is that many of the criteria are exclusionary. Causes of reactive neutrophilia such as underlying infection or a tumor as well as other myeloid malignancies such as myelofibrosis, polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDSs) must be ruled out. In addition, the BCR-ABL1 fusion as well as PDGFRA/B and FGFR1 rearrangements must be absent.8 The histopathologic and clinical features of CNL have been reviewed in detail elsewhere.9,10

Treatment options are limited for patients with CNL, with patients primarily receiving hydroxyurea and more rarely receiving interferon or a bone marrow transplant. CNL can progress to the more aggressive acute myeloid leukemia with a mean time to blast transformation of only 21 months.11 Furthermore, the median survival for patients after diagnosis was 21 or 23.5 months in 2 studies.11,12 Historically, our understanding of the genomics of CNL has been limited, with the majority of patients having normal cytogenetics.11,13 In part, the improvement of therapies for patients with CNL has been hampered by our limited understanding of the genetic and cellular underpinnings of the disease.

CSF3R mutations are a hallmark of CNL

A breakthrough in our understanding of the molecular basis of CNL came in 2013 with the discovery of colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R) mutations, also known as granulocyte colony–stimulating factor receptor (GCSFR), in the majority of patients (∼80%).12,14 Upon binding to its ligand (colony-stimulating factor 3 [CSF3] also known as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor [GCSF]), CSF3R acts to produce mature neutrophils in both steady state and demand granulopoiesis. CSF3R is critical for the differentiation and maturation of granulocyte progenitors into neutrophils.15 During systemic infection, signaling through the CSF3R pathway is thought to be a primary mechanism of increased neutrophil production.15

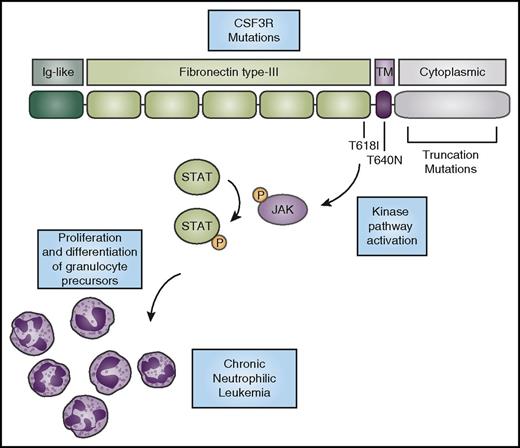

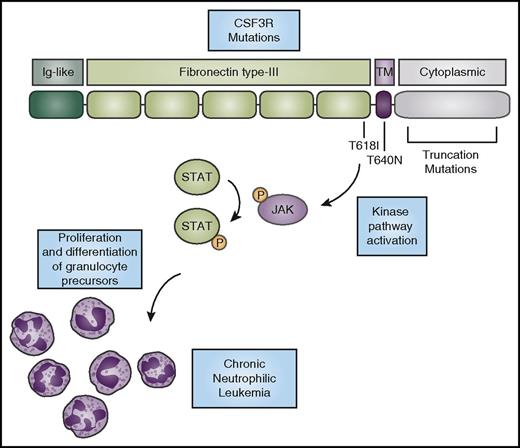

CNL-associated mutations in CSF3R activate the receptor through several mechanisms. It is thought that activation of the receptor through these mutations promotes the proliferation and differentiation of neutrophils, leading to the hyperproliferation of mature neutrophils that characterizes the CNL disease phenotype. Two primary types of mutations in CSF3R are observed in CNL (Figure 1). The first class encompasses point mutations in the extracellular or transmembrane domain of CSF3R. These include the most common mutation in CNL, T618I (also known as T595I using the historical numbering system for CSF3R, which does not include the first 23 amino acids that are part of the signal peptide).12,14 The other mutation seen outside the transmembrane domain, T615A, is found more rarely in CNL. Both the T618I and T615A mutations cause ligand-independent activation of the receptor.14,16 They also exhibit a shift in molecular weight banding pattern when analyzed by immunoblot, which is suggestive of an alteration in post-translational modification. Changes in glycosylation of the receptor were found in cells expressing mutated CSF3R.17 The precise relationship between post-translational modification and the ligand-independent dimerization of the receptor remains to be elucidated. The CSF3R extracellular point mutations are the most highly activating of the CSF3R mutations and are capable of inducing a lethal neutrophilia in a mouse bone marrow transplant model of disease.18

CSF3R mutations activate kinase signaling to promote the expansion of neutrophils. CSF3R has an N-terminal extracellular domain comprising an Ig-like domain (dark green) and fibronectin type-III repeats (light green). The T618I and T615A (not shown) mutations in the extracellular domain and the T640N mutation in the transmembrane domain (purple) cause ligand-independent receptor activation. Truncation mutations in the cytoplasmic domain (gray) cause increased cell-surface expression of the receptor. CNL-associated mutations in CSF3R cause activation of downstream kinase signaling pathways, such as the JAK/STAT pathway, ultimately driving neutrophil production. P, phosphorylation.

CSF3R mutations activate kinase signaling to promote the expansion of neutrophils. CSF3R has an N-terminal extracellular domain comprising an Ig-like domain (dark green) and fibronectin type-III repeats (light green). The T618I and T615A (not shown) mutations in the extracellular domain and the T640N mutation in the transmembrane domain (purple) cause ligand-independent receptor activation. Truncation mutations in the cytoplasmic domain (gray) cause increased cell-surface expression of the receptor. CNL-associated mutations in CSF3R cause activation of downstream kinase signaling pathways, such as the JAK/STAT pathway, ultimately driving neutrophil production. P, phosphorylation.

Another point mutation, T640N (also known as T617N), is rarely found in CNL.19 The T640N mutation was first reported in a family with congenital neutrophilia.20 This mutation, which resides within the transmembrane domain of the receptor, also causes ligand-independent activation. Molecular modeling predicted that the mutation would lead to hydrogen bonding between receptor pairs and thus induce dimerization within the transmembrane region.20 Indeed, biochemical studies showed that there was increased receptor dimerization in the presence of this mutation.19

The second class of CNL-associated mutations in CSF3R are nonsense or frameshift mutations that lead to a premature stop codon and truncation of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor.14 Patients with severe congenital neutropenia21 have a mutation in 1 of several genes critical for the production of neutrophils, such as neutrophil elastase. These patients receive long-term treatment with GCSF (the ligand for CSF3R) to combat their neutropenia and prevent the infections that are associated with low levels of neutrophils. After decades or years of treatment with GCSF, a subset of patients with severe congenital neutropenia develop acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which is correlated with the acquisition of CSF3R truncation mutations.22 Loss of a portion of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor can eliminate several negative regulatory motifs, depending on the precise location of the truncation mutation. These include binding sites for the suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3),23-25 which targets the receptor for lysosomal degradation after signaling,26 and the di-leucine sorting motif.27 These truncation mutations increase the cell surface expression of CSF3R, which in turn increases the activity of the receptor. Truncation of the receptor also alters its downstream signaling,25 which reduces the differentiative capacity of the receptor while continuing to allow for cellular proliferation. In a transgenic mouse model expressing the CSF3R truncation mutation, there is a reduction in steady-state neutrophil production,28,29 but hyperproliferation occurs in response to treatment with GCSF.29

In contrast to the CSF3R T618I mutation, the truncation mutations alone do not cause leukemia in mouse models,29 but they can accelerate the development of disease in the presence of another genetic event driving leukemia.30 Consistent with the in vivo data, the CSF3R truncation mutations display slower cell transformation kinetics than the T618I mutation in cellular assays14 and require ligand for the activation of downstream signaling pathways. Interestingly, in CNL, the CSF3R truncation mutations are almost always found in conjunction with the T618I or T615A mutations.9,14 Approximately 75% of patients with CNL/aCML who have CSF3R mutations exhibit only membrane-proximal mutations, whereas the other 25% of patients harbor both a membrane-proximal and a truncating-compound mutation.9 The scarcity of truncation mutations alone in CNL raises the possibility that truncation mutations alone are insufficient to drive the malignancy and that cooperating mutations in CSF3R or other genes may be required.

Although highly enriched in CNL, CSF3R mutations also occur in other hematologic malignancies. CSF3R mutations occur in aCML at a rate of 0% to 40%, with most aCML cohorts having few or no CSF3R-mutant patients.12,14,31,32 Those mutations are also rarely found in adult AML at a frequency of ∼0.5% to 1%.14,33 More recently, CSF3R mutations have been found in pediatric AML in ∼2% of patients.34,35 Both pediatric and adult AML patients with CSF3R mutations were found to exhibit significant enrichment for mutation of CEBPA.35,36 CSF3R mutations were also reported in 4% of patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML).37 In CMML, the mutations found were different than those in CNL or AML and the effect of these variants on protein function has not been established.37

Update to the WHO diagnostic criteria for CNL reflects new genetic information

In 2016, the WHO classification of hematologic malignancies was updated to reflect advances in our understanding of the genomics of these diseases (Table 1).38 For CNL, the presence of the CSF3R T618I mutation or other activating CSF3R mutations has become part of the diagnostic criteria.38 Patients can, however, still be classified as having CNL in the absence of a CSF3R mutation if they meet certain other criteria,38 such as having neutrophilia for at least 3 months, splenomegaly, and no detectable underlying reason for reactive neutrophilia.38 Reactive neutrophilia can be caused by an underlying infection or malignancy such as a plasma cell neoplasm.38 In the case of a plasma cell neoplasm, the diagnosis of CNL can still be made if there is evidence of myeloid cell clonality.38 The addition of CSF3R mutations to the criteria for CNL should allow for molecular in addition to phenotypic characterization of the disease entity to facilitate accurate diagnosis.

Other genetic findings

Recent genomic efforts in the setting of both CNL and aCML have revealed a greater genetic complexity than was previously appreciated. Overall, these additional mutations bear similarities to genetic events observed in other chronic myeloid malignancies and AML, with mutations being observed in the spliceosome complex and genes with roles in epigenetic modifications. In addition, although mutations in CSF3R remain prominent events, there have been some additional instances of mutations in genes that regulate cell proliferation, growth factors, and kinase signaling.

Additional genetic mutations.

SET binding protein 1 (SETBP1) mutations were discovered in 2012 in ∼25% of patients with aCML and were associated with significantly worse prognosis.39 Subsequent studies found that between 14% and 56% of patients with CNL also had SETBP1 mutations; the high degree of variability was likely a result of small cohort sizes.9,12,31,40 Among CNL patients, SETBP1 mutations are more likely to occur in those who harbor CSF3R mutations than in those who do not.9 SETBP1 was originally identified on the basis of its ability to bind SET oncoprotein through a yeast 2 hybrid screen.41 SET was previously implicated in leukemogenesis on the basis of the discovery that it can be part of a fusion protein with Nup214 in acute leukemia.42 SET was later found to be a negative regulator of the tumor suppressor protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which has many cellular roles, including inhibition of cellular proliferation.43 Overexpression of SETBP1 can increase levels of SET and inhibit PP2A.44 Interestingly, a subset of patients with AML have SETBP1 overexpression, which is associated with worse prognosis.44

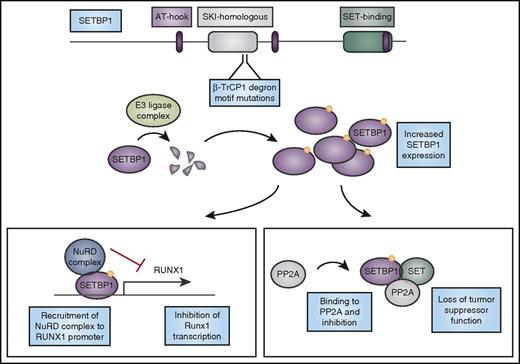

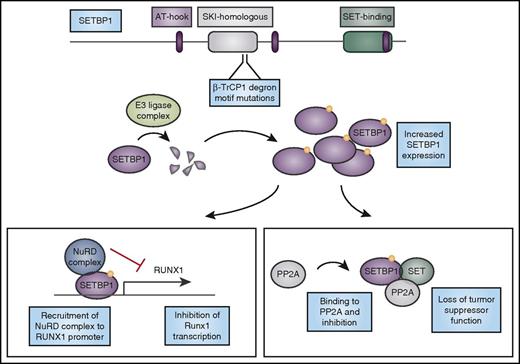

Mutations in SETBP1 associated with hematologic malignancies are largely identical to those found in patients with Schinzel-Giedion syndrome.39,45 The most prevalent SETBP1 mutations in myeloid malignancies are D868N and G870S. These mutations occur within the SKI-homology region and are specifically localized to a β-TrCP1 degron motif, which may target the protein for ubiquitin-mediated degradation.39 Mutations in this motif block binding of β-TrCP1 lead to increased expression of SETBP1 and reduced activity of PP2A.39 SETBP1 overexpression in a mouse bone marrow transplant model leads to myeloid leukemia with a long latency. In this model, SETBP1 overexpression decreases expression of Runx1, an important hematopoietic transcription factor.46 This repression of Runx1 expression at the messenger RNA level is mediated by recruitment of the nucleosome remodeling deacetylase (NuRD) complex to the Runx1 promoter by SETBP1.46 Negative regulation of Runx1, an important myeloid transcriptional regulation that is often mutated or dysregulated in leukemia, by SETBP1 provides further rationale for the importance of SETBP1 mutations in these myeloid leukemias (Figure 2). After their initial discovery in aCML, SETBP1 mutations were also found in a variety of myeloid malignancies, including secondary AML, CMML, juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, and MDS.37,47-49 In CMML, SETBP1 mutations seem to confer poor prognosis.50,51 Mutations in SETBP1 are therefore not specific to CNL.

Mutations in SETBP1 cause protein overexpression and lead to loss of tumor suppressor function and altered myeloid transcription factor expression. CNL-associated mutations in SETBP1 occur in the β-TrCP1 degron motif. β-TrCP1 binding leads to formation of an E3 ligase complex to degrade SETBP1. Mutations in the degron motif therefore lead to SETBP1 overexpression, which can cause stabilization of its binding partner SET, and together they can inhibit the tumor suppressor PP2A. In addition, SETBP1 binds to the RUNX1 promoter and when overexpressed, it recruits the nucleosome remodeling deacetylase (NuRD) complex to the RUNX1 promoter, inhibiting transcription of this important myeloid regulator. AT-hook, DNA-binding motif that prefers AT-rich sequences; SKI, V-Ski avian sarcoma viral oncogene homolog.

Mutations in SETBP1 cause protein overexpression and lead to loss of tumor suppressor function and altered myeloid transcription factor expression. CNL-associated mutations in SETBP1 occur in the β-TrCP1 degron motif. β-TrCP1 binding leads to formation of an E3 ligase complex to degrade SETBP1. Mutations in the degron motif therefore lead to SETBP1 overexpression, which can cause stabilization of its binding partner SET, and together they can inhibit the tumor suppressor PP2A. In addition, SETBP1 binds to the RUNX1 promoter and when overexpressed, it recruits the nucleosome remodeling deacetylase (NuRD) complex to the RUNX1 promoter, inhibiting transcription of this important myeloid regulator. AT-hook, DNA-binding motif that prefers AT-rich sequences; SKI, V-Ski avian sarcoma viral oncogene homolog.

Spliceosome mutations.

Spliceosome complex mutations were originally observed in MDSs and chronic lymphocytic leukemia,52-54 with mutations observed in the SRSF2, SF3B1, ZRSR2, and U2AF1 genes. These same mutational events were subsequently observed in other myeloid malignancies such as CMML55 and AML.56 Several of these events have also been observed in CNL and aCML, with reports of mutations in U2AF1 and SRSF2.31,57 Interestingly, the U2AF1 variants reported in CNL have predominately been observed at or near Q157, which is the less frequently reported variant hotspot of U2AF1 in myeloid malignancies overall.54 Mutations in this hotspot alter the splicing preferences of U2AF1 differently than the more common S34 variants, resulting in distinct aberrant splicing events. Although the rationale for the disproportionate frequency of residue Q157 U2AF1 variants remains unclear, it is interesting to postulate that an alternately spliced gene product resulting from the variants near Q157 (but not the S34 variants) could synergize with signaling pathways that are specific to CNL and aCML, such as mutant CSF3R signaling. It should also be noted that the CNL sample size from which this CSF3R/U2AF1 association was made is relatively small, so the observation bears validation in larger cohorts.

Epigenetic modifier mutations.

In addition to mutations in the spliceosome complex, a number of events have also been observed in genes that regulate epigenetic processes in both acute and chronic myeloid malignancies. A significant proportion of CNL and aCML patients have been shown to harbor ASXL1 mutations, with a mutational frequency of 30% to 60%.31,57,58 Similar to mutations in other myeloid malignancies, ASXL1 mutation in the setting of CNL was shown to confer poor prognosis.58 In addition to mutations in ASXL1, mutation of TET2 in 30% of CNL and 40% of aCML patients has also been observed.31 Sporadic events in other epigenetic modifying genes such as EZH2 and KDM6A have also been reported.57

Signaling mutations.

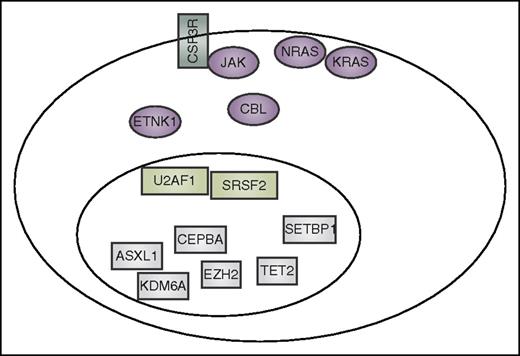

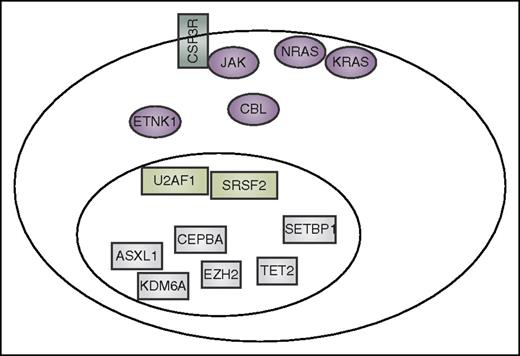

As noted above, mutation of CSF3R seems to be the most common mutational event in a signaling pathway in CNL, although it is less common in aCML. Mutation of SETBP1 is prevalent in both settings, although it is apparently less restricted in these disease subsets. Additional mutations in signaling pathway genes have been detected in CNL and aCML, with the most common events occurring in CBL, NRAS, KRAS, and JAK2, although at similar or lower frequency than is observed in other myeloid malignancies such as CMML or the classical myeloproliferative neoplasms.32,57,59 More recently, ETNK1 mutations have been detected in aCML60 with subsequent identification of similar mutations in CMML and systemic mastocytosis.61 A summary of the currently known mutated genes that co-occur in CNL and aCML is shown in Figure 3.

Summary of mutation currently reported to co-occur in CNL and aCML. These include CSF3R, other signaling genes (purple), spliceosome-associated genes (light green), and genes that have an impact on epigenetics and gene transcription (gray).

Summary of mutation currently reported to co-occur in CNL and aCML. These include CSF3R, other signaling genes (purple), spliceosome-associated genes (light green), and genes that have an impact on epigenetics and gene transcription (gray).

Commonalities with other myeloid malignancies

As noted above, many of the genetic events observed in CNL and aCML are also seen in other malignancies, particularly those of myeloid origin. In this regard, it is useful to consider the relative commonalities vs restriction of epigenetic, spliceosome, and signaling mutations for CNL and aCML vs other myeloid malignancies. As noted above, CSF3R mutations seem to be highly enriched in CNL and at a lower frequency in aCML. Other signaling events seem to occur at similar or higher frequencies in other myeloid malignancies.

Mutational events observed in epigenetic and splicing genes in CNL and aCML do not seem to be exclusive within this disease subset. Mutations in epigenetic regulators such as ASXL1, TET2, and EZH2 are observed in many other types of myeloid malignancies, usually at similar or higher frequency. Mutations in the spliceosome genes are seen at similar frequencies in other myeloid malignancies, although the apparent enrichment of the less common Q157 variant of U2AF1 in CSF3R-mutated CNL/aCML patients is intriguing.31,54,55

Taken together, the exclusivity of CSF3R mutations combined with the similarities of epigenetic and splicing mutations in CNL and aCML suggest that CSF3R mutations are acquired within a context and process of clonal hematopoiesis. Several studies in recent years have illustrated that clonal populations of hematopoietic cells, which become more prevalent in the aging population, are frequently associated with somatic mutations, especially in genes that regulate epigenetic processes.62-65 Notably, the most frequently mutated genes that have been observed in this process of clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP) are ASXL1 and TET2, which are commonly observed in CNL and aCML along with DNMT3A, which has not been reported in CNL and aCML. Hence, it is reasonable to postulate that the CSF3R mutations observed exclusively in CNL and aCML impart a distinct neutrophilic phenotype within the context of a more general process of clonal hematopoiesis. The absence of CSF3R variants within the large CHIP cohort data sets published in 2014 suggest that CSF3R variants are unlikely to serve as the initiating lesion for CHIP, but the prevalence of CHIP variants such as TET2 and ASXL1 that co-occur with CSF3R variants suggests that CSF3R mutation may often be a later occurring event that imparts a neutrophilic phenotype to a preexisting CHIP process. Indeed, as more genomic data are collected for CNL and aCML patients, it will be critical to understand the frequencies of other CHIP-associated mutant genes, which could lead to the establishment of a more precise diagnostic sequencing panel for these diseases.

CNL and aCML are predominantly diseases of age-related clonal hematopoiesis

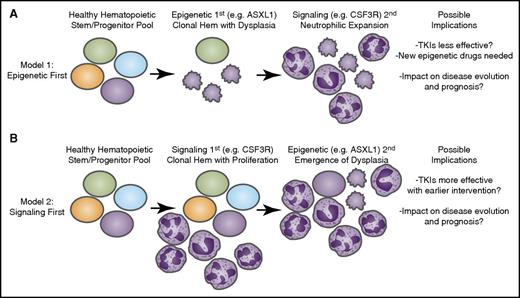

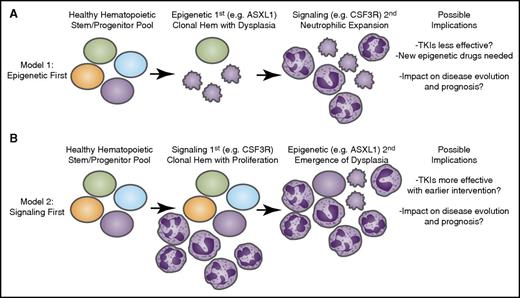

The observation that CSF3R mutations frequently co-occur with other somatic variants commonly associated with age-related clonal hematopoiesis raises many important questions regarding the biology of mutational acquisition as well as the impact that various biological models may have on clinical parameters of the disease. There are at least 3 distinct models for clonal evolution and mutation acquisition that can be envisioned from the baseline, diagnostic sequencing data available to date (Figure 4).

Longitudinal acquisition of mutations may have an impact on disease course and therapeutic strategies. Recent genomic findings in CNL and aCML have indicated that mutations may arise in at least 3 different categories of genes: epigenetic modifiers, components of the spliceosome, and growth factor signaling pathways. It is likely that these mutations are acquired through a process of age-related clonal hematopoiesis (Hem) in which 1 of these mutational events initiates (A) a dysplastic or (B) a proliferative anomaly with subsequent acquisition of the other gene categories resulting in evolution to overt disease. The identity of the gene that initiates this process may have important implications for the manner in which the disease proceeds down distinct diagnostic trajectories as well as the possibility for success of targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as well as emerging agents that target epigenetic or splicing processes.

Longitudinal acquisition of mutations may have an impact on disease course and therapeutic strategies. Recent genomic findings in CNL and aCML have indicated that mutations may arise in at least 3 different categories of genes: epigenetic modifiers, components of the spliceosome, and growth factor signaling pathways. It is likely that these mutations are acquired through a process of age-related clonal hematopoiesis (Hem) in which 1 of these mutational events initiates (A) a dysplastic or (B) a proliferative anomaly with subsequent acquisition of the other gene categories resulting in evolution to overt disease. The identity of the gene that initiates this process may have important implications for the manner in which the disease proceeds down distinct diagnostic trajectories as well as the possibility for success of targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) as well as emerging agents that target epigenetic or splicing processes.

Three models for clonal evolution and mutation acquisition

Model 1: CSF3R (or other signaling pathway) mutations occur as a secondary event within a context of clonal hematopoiesis.

In the first model, a process of clonal hematopoiesis is originally associated with somatically acquired variants in genes that regulate epigenetic (eg, TET2, ASXL1) and/or splicing (eg, SRSF2, U2AF1) processes. This setting of clonal hematopoiesis is likely asymptomatic at the onset or possibly exhibits features of myelodysplasia, but acquisition of a signaling mutation gives the clonal hematopoietic population a distinctive cell lineage phenotype. In patients with aCML and especially CNL, it seems that this signaling mutation occurs frequently in CSF3R leading to a neutrophil lineage bias, similar to the way in which mutations in JAK2/MPL/CALR give the traditional myeloproliferative neoplasms a bias toward red cell and/or platelet lineage phenotypes (Figure 4A).

Model 2: The initial proliferative stage associated with CSF3R (or other signaling pathway) mutation is exacerbated by mutation(s) in epigenetic/splicing genes.

In the second model, it seems plausible that certain cases of CNL/aCML are derived from an originating mutation in CSF3R or other signaling pathway genes, imparting a myeloproliferative state. Because patients with CNL/aCML who have only mutations in CSF3R are apparently rare, it seems likely that the clone evolves to acquire additional mutations in epigenetic/splicing genes, which amplify the disease process, potentially adding dysplastic features. This might be similar to cases of Philadelphia chromosome 1–positive CML or traditional myeloproliferative neoplasms that acquire mutations in epigenetic/splicing genes upon a disease transformation event (Figure 4B).

Model 3: Acquisition of mutations in distinct clonal populations of cells.

The third model is the least likely to occur. On the basis of high and generally similar variant allele frequencies of CSF3R, SETBP1, ASXL1, and other genetic events seen in CNL and aCML, it is highly unlikely (and in many cases impossible) that these events could be segregated into completely distinct clonal populations. Nonetheless, it is possible that in certain cases, the spectrum of mutations observed in a given patient’s tumor cells could be present in a heterogeneous population of distinct clones, each harboring one or more variant. Although it is highly unlikely that distinct clones with prevalent variants are frequently co-occurring in CNL/aCML patients, it is likely that some oligoclonality with heterogeneous mutation distribution is observed in some patients, as has frequently been reported in AML and other tumors.

Impact of genetic findings on understanding and management of disease

The order of acquisition of somatic mutations as patients with CNL/aCML clonally evolve may have a direct impact on clinical management. Model 1, in which epigenetic/splicing mutations are acquired first with CSF3R mutation or other signaling events occurring later to impart a neutrophilic preference for lineage commitment, is compelling in the context of the specific mutations commonly associated with clonal hematopoiesis often being the very same epigenetic and splicing gene mutations observed in these diseases. However, recent studies in other related disorders, particularly the traditional myeloproliferative neoplasms, have indicated that the order of acquisition is not uniform across patient populations. Indeed, single-cell analyses from patients with polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, or primary myelofibrosis revealed that some patients acquired epigenetic events such as TET2 mutations before acquisition of signaling lesions such as JAK2 V617F, but that there were also patients in whom the opposite was true.66 The specific model of clonal evolution into which a given patient’s disease falls may have important clinical implications in at least 3 areas.

Diagnostic implications

Because mutation of CSF3R has now been included as one of the diagnostic criteria for CNL, the knowledge that CSF3R mutations may occur later in disease evolution could have implications for the diagnosis of this disease. Indeed, there is already at least 1 report of a patient who was initially diagnosed with MDS evolving to refractory anemia with excess blasts with complex karyotype without CSF3R mutation, and the disease subsequently evolved further to a phenotype resembling CNL/aCML. At this later disease stage, the tumor was found to have acquired a new mutation in CSF3R.19 Therefore, it will be important to consider longitudinal genetic testing to best understand disease evolution. In addition, although CSF3R mutations are heavily enriched within the CNL diagnostic subset, there are patients who meet all WHO criteria for aCML and exhibit CSF3R mutations.19,67,68 Going forward, it will be important to consider whether patients with CSF3R mutations should all be placed into a single category or whether they should sometimes remain stratified into distinct groups according to their disease. The spectrum of additional mutations seen in these patients, as well as the order of acquisition of these mutations, may play a role in deciding which categories patients with CSF3R mutations should be placed in.

Prognostic implications

Several of the genetic features associated with CNL and aCML have been associated with disease prognosis. Although sample sizes were small, CNL and aCML patients who exhibited SETBP1 or ASXL1 variants were shown to exhibit worse prognosis whereas CSF3R variants were not prognostically significant. Correlation of event-free or overall survival with other genetic features of these diseases, such as spliceosome mutations, has not yet been assessed.

Therapeutic implications

In addition to diagnostic and prognostic considerations, the pattern of tumor mutational architecture and acquisition may also have implications for therapeutic strategies and efficacy. Because mutant CSF3R has been shown to lead to dysregulated JAK/STAT signaling, it has been suggested that JAK inhibitors, such as ruxolitinib, may be efficacious in treating CSF3R-mutant CNL/aCML, and a trial (NCT02092324) is currently in progress to prospectively assess this possibility. Indeed, early and recent anecdotal cases suggested some clinical benefit of ruxolitinib in treating CSF3R-mutant patients.14,67,69 However, there have also been reports of patients in whom a CSF3R mutation was present but there was no response to ruxolitinib, which suggests that additional genetic events, such as a SETBP1 mutation, may abrogate response.70,71 As more patients are treated with targeted therapies, such as JAK/STAT pathway inhibitors, it will be important to ascertain the response rates of patients with CSF3R-mutant vs wild-type disease and to place these responses into a context of the additional genetic events present in each patient (eg, SETBP1, ASXL1). It will also be important to understand whether patients with early acquisition of CSF3R mutation may exhibit superior response compared with patients in whom CSF3R mutations are later-occurring events in the evolution of disease. The pattern of mutation acquisition may, in fact, help resolve some of the contradictory reports of JAK inhibitor efficacy within this patient population.

In conclusion, CSF3R mutations are highly prevalent in CNL. Given the endogenous function of CSF3R in the proliferation and differentiation of neutrophils, it is likely that CSF3R mutations are key in driving this rare and specific disease phenotype. Recent genomic evidence, however, demonstrates that CSF3R mutations are not acting in isolation. Mutations in SETBP1, spliceosome proteins, and epigenetic regulators are also present in CNL and are similar to those mutations found in other myeloid malignancies and in age-related clonal hematopoiesis. Future studies on the order in which these mutations occur and their interaction with mutated CSF3R will provide insight into the biogenesis and therapeutic targeting of this rare but serious myeloid malignancy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an American Society of Hematology Scholar Award and by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (4R00CA190605-03) (J.E.M.), and by The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, the V Foundation for Cancer Research, Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation for Cancer Research, and the NCI (5R00CA151457-04, 1R01CA183947-01) (J.W.T.).

Authorship

Contribution: J.E.M. and J.W.T. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.W.T. received research support from Agios Pharmaceuticals, Array BioPharma, Aptose Biosciences, AstraZeneca, Constellation Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Incyte, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Seattle Genetics, Syros Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals and is a consultant for Leap Oncology. The remaining author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jeffrey W. Tyner, Oregon Health & Science University, Knight Cancer Institute, BRB 511, Mailcode L592, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239; e-mail: tynerj@ohsu.edu.