Key Points

Strong complement activation overrides the terminal pathway inhibition by the anti-C5 antibody eculizumab.

The more powerful complement is activated, the less effective is terminal pathway inhibition by diverse anti-C5 agents.

Abstract

Eculizumab inhibits the terminal, lytic pathway of complement by blocking the activation of the complement protein C5 and shows remarkable clinical benefits in certain complement-mediated diseases. However, several reports suggest that activation of C5 is not always completely suppressed in patients even under excess of eculizumab over C5, indicating that residual C5 activity may derogate the drug’s therapeutic benefit under certain conditions. By using eculizumab and the tick-derived C5 inhibitor coversin, we determined conditions ex vivo in which C5 inhibition is incomplete. The degree of such residual lytic activity depended on the strength of the complement activator and the resulting surface density of the complement activation product C3b, which autoamplifies via the alternative pathway (AP) amplification loop. We show that at high C3b densities required for binding and activation of C5, both inhibitors reduce but do not abolish this interaction. The decrease of C5 binding to C3b clusters in the presence of C5 inhibitors correlated with the levels of residual hemolysis. However, by employing different C5 inhibitors simultaneously, residual hemolytic activity could be abolished. The importance of AP-produced C3b clusters for C5 activation in the presence of eculizumab was corroborated by the finding that residual hemolysis after forceful activation of the classical pathway could be reduced by blocking the AP. By providing insights into C5 activation and inhibition, our study delivers the rationale for the clinically observed phenomenon of residual terminal pathway activity under eculizumab treatment with important implications for anti-C5 therapy in general.

Introduction

Eculizumab, a commercial C5 blocking antibody, shows remarkable clinical benefits for the diseases paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH)1,2 and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS).3 Both conditions are characterized by hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, thrombosis, and organ damage due to insufficiently regulated or overly active complement activation.4,5 Promising clinical results were also reported in several studies where eculizumab therapy was evaluated in other diseases with complement involvement.6-10

Eculizumab binds C5 with picomolar affinity and inhibits its enzymatic activation by C5 convertases, possibly through steric hindrance.11,12 However, a recent study indicates that eculizumab not only acts sterically, by blocking binding to the C5 convertase, but also prevents C5 to adopt a primed conformation that is susceptible to processing by the C5 convertase.13 A similar mechanism has been suggested for the tick inhibitor OmCI (Ornithodoros moubata complement inhibitor) or its recombinant version, coversin, which binds C5 at the face opposite to the eculizumab epitope.13-15

By blocking C5 activation, C5 inhibitors impair inflammatory signaling by the anaphylatoxin C5a and cell lysis mediated by the membrane attack complex (MAC).11 The initiation of the terminal pathway (TP) via assembly of C5 convertases is achieved through the activation of any of the three canonical activation routes: the classical pathway (CP), lectin pathway (LP), and alternative pathway (AP).16 Activation of the CP (by immune complexes) and LP (by danger patterns) leads to the formation of the CP C3-convertase (C4b2a) that proteolytically activates the central complement protein C3 into the anaphylatoxin C3a and the larger fragment C3b, which may covalently attach to carbohydrates or proteins on cell surfaces. The unique feature of the AP is that it is constantly and autonomously activated at a low level (termed “tick-over”) for immune surveillance to indiscriminately probe available surfaces.17

Healthy cells are protected from constant AP probing through surface-bound regulators and self-recognition by soluble regulators such as factor H (FH).16,18 Low level tick-over activation initially produces only small amounts of C3b. If not inactivated immediately by regulators, any generated C3b molecules, regardless of whether they originate from the CP/LP or AP, assemble the bimolecular C3 convertases of the AP (C3bBb) to produce more C3b molecules, thus amplifying themselves in the positive feedback loop of the AP (for a comprehensive graphical representation, see Schmidt et al19 ). This self-propagation increases the surface density of C3b and thus appears to foster the recruiting of an additional C3b molecule to bimolecular C3 convertases (C4b2a or C3bBb) to form the trimolecular C5 convertases (C4b2a3b or C3bBb3b).16 Other concepts propose that the additional C3b molecules bind and prepare (ie, “prime”) C5 for proteolytic activation instead of interacting directly with the convertase unit.20-22

Proteolytic activation of C5 marks the initiation of the TP. Apart from direct damage due to the disease-underlying imbalance between AP activation and regulation in aHUS and PNH, the TP activation products C5a and MAC promote a generalized prothrombotic status, which is the major cause of organ damage and mortality (reviewed in Noris and Remuzzi5 and Hill et al23 ). Under eculizumab therapy, remarkable reductions in thromboses were observed, providing clinical evidence that TP activity is responsible for thrombotic complications.24-26 Despite profound improvements in the clinical management of PNH and aHUS, there are reports of incomplete or even absence of therapeutic responses under eculizumab. Nonresponders are the few patients with a rare single-nucleotide polymorphism in C5.27 While breakthrough hemolysis leading to intravascular hemolysis is rare, the more commonly observed incomplete response in PNH patients is ascribed to the phenomenon of extravascular hemolysis.28-30 Due to the underregulated AP, PNH erythrocytes (PNH-RBCs) become covalently marked with complement C3 opsonins but do not lyse, because the TP is blocked by eculizumab. However, accumulating C3 opsonins on PNH-RBCs are recognized by complement receptors on macrophages and thus are phagocytosed, causing extravascular hemolysis.31 Despite the compelling data in support of extravascular clearance, this phenomenon can only partly explain the ongoing low-level hemolysis observed in some PNH patients. For example, Peffault de Latour et al32 did not notice a correlation between the level of C3 opsonization and signs of hemolysis within their cohort of PNH patients and concluded that residual hemolysis under eculizumab may be due to other causes, such as individual genetic polymorphisms.

Similarly, not all aHUS patients experience optimal response to eculizumab. Although certain in vitro diagnostic assays indicate complete suppression of CH50 and AH50 under eculizumab, in vivo complement activation can occur at relapse and is evident from elevated TP activation products.33 A similar observation was described in 2 cases of eculizumab treatment in the context of kidney transplantation, indicating that in some cases complete inhibition of TP activity may not be possible even at higher-than-normal eculizumab doses.34,35 Hence, we set out to investigate whether the clinically observed residual TP activity under eculizumab treatment is mechanistically related to C5 activation by C5 convertases and how it can be overcome.

Methods

Human blood components

PNH-RBCs from patients under eculizumab treatment (designated A-G) as well as normal and patient sera were used under approval by the ethical committee of Ulm University. PNH-RBCs were used immediately or after storage in liquid nitrogen.36 The fraction of PNH-RBCs type III was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.37 Sera were collected in VACUETTE/S-Monovette serum collection tubes, aliquoted, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. Factor B–depleted (FB-dpl) serum, factor I–depleted serum, and standardized normal human serum (NHS) were obtained from CompTech. C5-depleted serum was from Quidel.

Proteins

Eculizumab (Soliris) was obtained from remnants in infusion pipes. A recombinant version of the natural tick-derived C5 inhibitor OmCI and its PASylated form, PAS-coversin, were expressed with an N-terminal His6-tag in Escherichia coli from codon-optimized genes.15 C5 and an anti–human C5 monoclonal antibody (clone 046-10.2.2) were purchased from Quidel. The minimized engineered version of the natural AP regulator FH, mini-FH, and the C-terminal FH fragment, FH18-20, which harbors the FH host surface recognition patch, were produced as described previously.38,39

Hemolysis and bacterial lysis assays

CP activity was measured with a standard heterologous hemolysis assay using antibody-sensitized sheep erythrocytes (shRBCs).40 Alternatively, a very sensitive homologous assay with antibody-sensitized PNH-RBCs was adapted from the procedure of Rosse.41 AP activity was detected with rabbit erythrocytes (rRBCs), which spontaneously activate human complement, or with PNH-RBCs that lyse in an AP-dependent manner when the pH of NHS is lowered.42-44 Detailed descriptions are given in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site.

Binding of C5 to C3b monitored by surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

Coupling of C3b to the sensor chip and binding analysis was performed as described previously45 and detailed in supplemental Methods. The following analytes were applied as indicated: C5 alone, C5 with excess amounts of eculizumab or coversin, or a mix of eculizumab and coversin.

Results

Single C5 inhibition only partially blocks TP activation

We tested the capacity of eculizumab to inhibit TP activity in a common CP-mediated hemolysis assay on shRBCs in the presence of human serum. In order to evaluate the effects of C5 inhibition on complement activity on a more general basis, we included other C5 inhibitory agents. These were the clinically developed 17-kDa protein coversin (www.clinicaltrials.gov #NCT02591862), which binds C5 with high affinity and prevents proteolytic activation of C5,14,46 and a modified version of coversin using PASylation, PAS-coversin. PAS-coversin comprises an N-terminal fusion with a 600-residue polypeptide composed of Pro, Ala, and Ser (PAS15,47 ) to increase the intrinsically short plasma half-life of free coversin (not bound to C5).

All C5 inhibitors prevented lysis of the sensitized shRBCs in a dose-dependent manner. Eculizumab can bind 2 C5 molecules and thus inhibits TP activity at half the molar concentrations of coversin and PAS-coversin, which bind C5 in 1:1 stoichiometry (Figure 1A). We then tested these C5 inhibitors in a standard AP-mediated hemolysis assay on rRBCs in human serum. rRBCs activate the human AP in the absence of additional sensitization. As a control, the minimized, engineered version of the natural AP-specific regulator FH, mini-FH, was included; mini-FH regulates the complement cascade upstream of C5 activation and inhibits at the level of activated C3.38 All inhibitors showed a clear concentration-dependent inhibition of hemolysis, but only mini-FH inhibited lysis completely, while all C5 inhibitors in the assay reached a plateau of background lysis and failed to completely inhibit hemolysis, even at higher inhibitor concentrations (Figure 1B). Of note, the level of background hemolysis was different for the C5 inhibitors. Coversin exhibited the highest plateau, followed by eculizumab and PAS-coversin, of which the latter exhibited advantageous inhibitory features compared with coversin. That coversin and eculizumab do not achieve full inhibition of AP-mediated lysis on rRBCs is consistent with previous observations.14,48 Remarkably, when both of these C5 inhibitors were applied simultaneously, full protection of rRBCs was achieved, indicating a synergistic effect via double inhibition of C5.

Different C5 inhibitors reveal residual TP activity on foreign activating cells. (A) CP-mediated lysis of shRBCs. Hemolysin-treated shRBCs were mixed with 5% serum in the presence of specific inhibitors. Released hemoglobin was measured as a marker of hemolysis (the average of 3 independent assays with standard deviation [SD] is shown). (B) AP-mediated lysis of rabbit erythrocytes. Rabbit erythrocytes were incubated in 25% human serum in presence of inhibitors or controls (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (C) Different combinations of C5 inhibitors protect rRBCs. As in panel B, but eculizumab and another commercial anti-C5 antibody (clone: 046-10.2.2) were used at concentrations that substantially exceed the typical C5 concentration of the serum dilution in this assay (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (D-E) TP activity of serum from PNH patients on eculizumab. rRBCs were incubated in 25% human serum derived from 2 PNH patients (#A and #B) on eculizumab in absence or presence of additional complement inhibitors as indicated (average of 2 independent assays with SD is shown). (F) Determination of free C5 levels through sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using eculizumab as capture antibody and a polyclonal anti-C5 as a detection antibody. Eculizumab deposited on the microtiter plate captures free C5 from NHS, but not when NHS has been premixed with 0.5 µM eculizumab. No free C5 was captured from patient serum or patient serum that had been diluted 1:1 (1-in-2) with NHS (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown; the NHS/eculizumab mixture [negative control] was only assayed twice). Ecu, eculizumab; PAS-Cov., PASylated Coversin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PBSE, PBS supplemented with EDTA (to 5 mM).

Different C5 inhibitors reveal residual TP activity on foreign activating cells. (A) CP-mediated lysis of shRBCs. Hemolysin-treated shRBCs were mixed with 5% serum in the presence of specific inhibitors. Released hemoglobin was measured as a marker of hemolysis (the average of 3 independent assays with standard deviation [SD] is shown). (B) AP-mediated lysis of rabbit erythrocytes. Rabbit erythrocytes were incubated in 25% human serum in presence of inhibitors or controls (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (C) Different combinations of C5 inhibitors protect rRBCs. As in panel B, but eculizumab and another commercial anti-C5 antibody (clone: 046-10.2.2) were used at concentrations that substantially exceed the typical C5 concentration of the serum dilution in this assay (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (D-E) TP activity of serum from PNH patients on eculizumab. rRBCs were incubated in 25% human serum derived from 2 PNH patients (#A and #B) on eculizumab in absence or presence of additional complement inhibitors as indicated (average of 2 independent assays with SD is shown). (F) Determination of free C5 levels through sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using eculizumab as capture antibody and a polyclonal anti-C5 as a detection antibody. Eculizumab deposited on the microtiter plate captures free C5 from NHS, but not when NHS has been premixed with 0.5 µM eculizumab. No free C5 was captured from patient serum or patient serum that had been diluted 1:1 (1-in-2) with NHS (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown; the NHS/eculizumab mixture [negative control] was only assayed twice). Ecu, eculizumab; PAS-Cov., PASylated Coversin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PBSE, PBS supplemented with EDTA (to 5 mM).

To test whether incomplete C5 inhibition by eculizumab generally can be alleviated by addition of a second C5 inhibitor that binds to an orthogonal C5 epitope (supplemental Figure 1), we employed the rRBC hemolysis assay to test the activity of a commercially available anti-C5 antibody (clone 046-10.2.2) alone and in combination with eculizumab (Figure 1C). The anti-C5 antibody showed only a marginal reduction of TP activity. However, when the anti-C5 antibody was combined with eculizumab, hemolysis was inhibited to levels similar to those seen under double inhibition of eculizumab and coversin, suggesting that the synergistic action of 2 independent C5 inhibitors is a more general feature.

We then probed if this phenomenon of residual TP activity on AP-inducing rRBCs could also be observed in serum from PNH patients treated with eculizumab. Since patient-derived serum already contains eculizumab, the sharp decline in hemolysis upon addition of the inhibitors (as seen in Figure 1A) is not observed; instead, the graph displays background hemolysis under eculizumab. Both patient sera exhibited, ex vivo, a residual background hemolysis of rRBCs of ∼25% (Figure 1D-E; supplemental Table 1). As little as 0.5% of the normally in serum available functional C5 amount is needed to produce such a 25% level of background hemolysis (supplemental Figure 2). Further ex vivo addition of eculizumab in the assay only marginally reduced the residual hemolytic activity (Figure 1D-E). In contrast, addition of mini-FH showed the most pronounced protective effect. This is consistent with previous data showing that the C3-opsonin–targeting inhibitors mini-FH and TT30 efficiently control AP activation in several assays.38,44,45,49,50 As observed for the double inhibition of C5 in NHS (above), addition of coversin or PAS-coversin to the patient-derived, eculizumab-containing serum completely stopped the residual hemolysis if compared with eculizumab alone. We verified that the patient sera indeed contained an excess amount of eculizumab over C5 (Figure 1F).

Next, we tested whether residual TP activity is also observed for bacteria that forcefully activate complement. As expected, C5 inhibition by eculizumab also failed to completely inhibit TP activity on E coli (supplemental Figure 3).

Taken together, residual TP activity is evident under different C5-inhibition strategies but can be blocked by employing a C3-opsonin–targeted inhibitor that acts earlier in the complement cascade or by employing 2 C5 inhibitors simultaneously (supplemental Table 2).

Residual lysis under C5 inhibition is influenced by AP activity

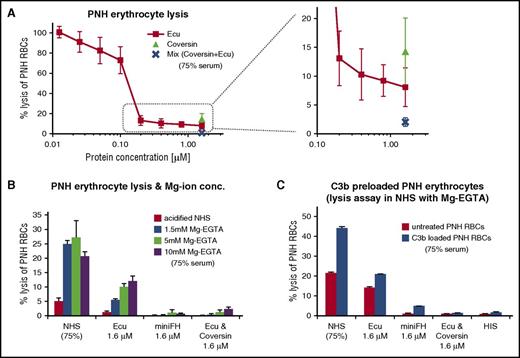

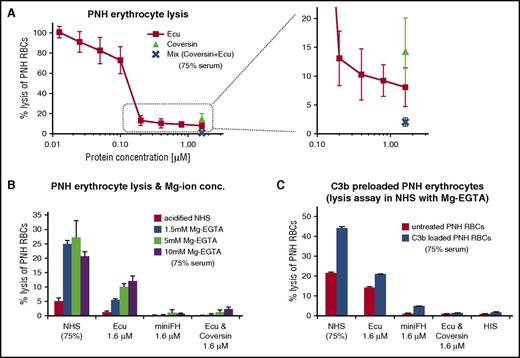

Unlike the foreign surfaces of rRBCs and bacteria that forcefully activate complement, the host surfaces on PNH-RBCs are nonactivators and do not lyse readily in absence of a complement activation trigger.51 We evaluated whether the aspect of residual TP activity under C5 inhibition can also be observed on human PNH-RBCs. Therefore, we employed a modified form of the acidified serum assay with PNH-RBCs. Residual hemolysis at excess amounts of eculizumab also occurred on PNH-RBCs but was low in comparison with foreign cell surfaces. Consistent with the findings above, coversin alone was less efficient in protecting PNH-RBCs, whereas C5 double inhibition with coversin and eculizumab achieved the best results (Figure 2A).

Forceful AP activation reveals TP activity in C5-inhibited serum on PNH cells. (A) Protection of PNH cells from complement alternative pathway mediated lysis. PNH-RBCs were incubated for 24h in acidified human serum mixed with complement inhibitors (75% final serum concentration; average of 3 independent assays with SD). (B) As in panel A, but with addition of Mg-EGTA (whereby EGTA chelates Ca ions to block CP activity) to the serum, with an incubation time at 37°C for 2 hours. Hemolysis was measured by determining the release of hemoglobin at 405 nm (1 typical assay out of 3 independent assays with average values of triplicate data points with SD is shown; for the other 2 assays, see supplemental Figure 5 A-B). (C) Residual hemolysis of PNH-RBCs preloaded with C3b in C5-inhibited serum. PNH-RBCs were preloaded with C3b in human factor I–depleted serum under combined C5 inhibition (with eculizumab and coversin) to allow for efficient C3b opsonization without lysis. C3b preloaded cells were washed and then exposed to 75% human serum in absence or presence of the inhibitors. The C3b-preloaded PNH cells were incubated for 2 hours in acidified human serum supplemented with 5 mM Mg-EGTA (1 typical assay out of 3 independent assays with average values of duplicate data points with SD is shown; for the 2 other assays, see supplemental Figure 5C-D). Ecu, eculizumab; HIS, heat-inactivated serum.

Forceful AP activation reveals TP activity in C5-inhibited serum on PNH cells. (A) Protection of PNH cells from complement alternative pathway mediated lysis. PNH-RBCs were incubated for 24h in acidified human serum mixed with complement inhibitors (75% final serum concentration; average of 3 independent assays with SD). (B) As in panel A, but with addition of Mg-EGTA (whereby EGTA chelates Ca ions to block CP activity) to the serum, with an incubation time at 37°C for 2 hours. Hemolysis was measured by determining the release of hemoglobin at 405 nm (1 typical assay out of 3 independent assays with average values of triplicate data points with SD is shown; for the other 2 assays, see supplemental Figure 5 A-B). (C) Residual hemolysis of PNH-RBCs preloaded with C3b in C5-inhibited serum. PNH-RBCs were preloaded with C3b in human factor I–depleted serum under combined C5 inhibition (with eculizumab and coversin) to allow for efficient C3b opsonization without lysis. C3b preloaded cells were washed and then exposed to 75% human serum in absence or presence of the inhibitors. The C3b-preloaded PNH cells were incubated for 2 hours in acidified human serum supplemented with 5 mM Mg-EGTA (1 typical assay out of 3 independent assays with average values of duplicate data points with SD is shown; for the 2 other assays, see supplemental Figure 5C-D). Ecu, eculizumab; HIS, heat-inactivated serum.

Previous studies have shown that C5 activation correlates with C3b surface deposition21,22,52 and densities20 and that C5 apparently necessitates a priming event in form of a conformational change after binding to C3b (in order to allow proteolytic activation by C5 convertases13 ). Hence, we hypothesized that the AP amplification loop is important for the production of sufficient C3b densities in our PNH model. The hypothesis predicts that lower C3b densities suffice for activation of free C5, which is not blocked by an inhibitor, whereas higher C3b densities help to promote residual C5 activation in presence of a C5 inhibitor like coversin or eculizumab. When compared with strong, foreign activators of the AP, PNH-RBCs exhibited only small residual hemolysis under C5 inhibition. Therefore, we investigated whether a higher activity of the AP, by increasing Mg-ion concentrations, generates higher levels of residual hemolysis on PNH-RBCs. Indeed, elevated Mg-ion concentrations generally increased hemolysis levels (Figure 2B) in serum alone or in presence of a single C5 inhibitor. Inhibition by mini-FH or double C5 inhibition with eculizumab and coversin protected all cells from lysis, consistent with the findings above.

Maintaining these in vitro conditions that maintain higher AP activity (ie, 5mM Mg-EGTA) we probed the hypothesis that higher C3b densities directly increase the background hemolysis level under C5 inhibition. We preloaded PNH-RBCs with C3b molecules by exposure to factor I–depleted serum under C5 double inhibition to efficiently decorate the cells with C3b but prevent lysis at this preconditioning step. Preconditioning did achieve high C3b densities, which were evident from erythrocyte agglutination or FACS analysis. C3b-loaded PNH-RBCs did indeed exhibit higher levels of residual hemolysis under eculizumab, but double inhibition with eculizumab and coversin conferred full protection, while inhibition with mini-FH was the most efficient singular inhibitor in this assay (Figure 2C).

In summary, PNH-RBCs only exhibit low levels of residual hemolysis in the presence of eculizumab. Under conditions that generate high C3b surface densities by favoring powerful activation of the AP or preloading cells with C3b, substantial levels of residual TP activity are evident but can be efficiently inhibited with mini-FH or a combined C5 block involving the 2 independent C5 inhibitors eculizumab and coversin.

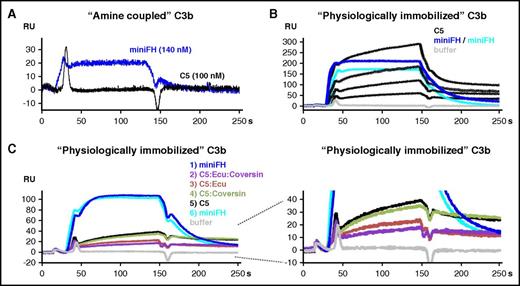

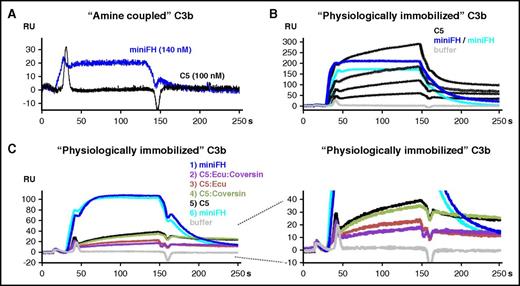

C5 inhibitors reduce but do not abolish binding of C5 to C3b clusters

C5 binding to C3b is a prerequisite for C5 activation, as several studies have demonstrated.13,20-22 While it is generally accepted that C5 inhibition by coversin or eculizumab abolishes TP-mediated lysis and inflammation, our data show that during strong complement activation, substantial levels of residual C5 activity can be observed in the presence of C5 inhibitors. Since one function of the AP is to produce high densities of C3b molecules, we employed SPR to investigate the direct influence of C3b deposition and density on the binding of C5 in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Immobilization of 800 response units (RUs) of C3b onto the carboxymethyldextran surface of a sensor chip via standard amine coupling enabled binding of mini-FH (Figure 3A) as expected.38,45 In contrast, no binding of C5 to amine coupled C3b was observed. However, when additional 900 RUs of C3b molecules were immobilized in a more physiological manner employing on-chip assembled C3 convertases, C5 did efficiently adhere to such “physiologically” immobilized C3b in a concentration-dependent way (Figure 3B). C5 mixed with both eculizumab and coversin exhibited the smallest binding response, followed by the C5:eculizumab and the C5:coversin mixtures, whereas C5 alone resulted in the highest response (Figure 3C). Thus, although the level of C5 binding in the presence of inhibitors to the physiologically deposited C3b correlated with the levels of residual hemolysis observed above, the inhibitors never completely prevented C5 binding to C3b surface clusters, indicating an inhibitory mechanism that is distinct from sole steric hindrance. Another SPR experiment with 2500 RUs C3b, again immobilized by amine coupling, showed that C5 reproducibly binds to C3b, although the levels are lower when compared with the more physiologically prepared surface (supplemental Figure 4). Formation of C3bBb on this surface did not increase C5 binding in comparison with the C3b surface alone.

SPR analysis of C5 binding to C3b. (A) Binding of C5 and mini-FH to C3b immobilized on a carboxymethyldextran-coated sensor chip by amine coupling (800 RUs). Mini-FH at a concentration of 140 nM or C5 at 100 nM was applied to the C3b surface (reference-subtracted responses are shown throughout). (B) C5 binding to “physiologically,” convertase-immobilized C3b. C3 convertases were assembled onto the amine coupled C3b sensor chip followed by flow of C3, which becomes activated in situ and binds covalently. According to this procedure, another 900 RUs of C3b were immobilized in a physiological manner via the convertase onto the 800 RUs of amine-coupled C3b. Mini-FH was assayed at 1.5 µM in 2 consecutive injections (2 overlaid dark blue curves), followed by C5 at 1.1, 0.6, 0.3, and 0.1 µM (black curves) and then another injection of mini-FH at 1.5 µM (cyan). The lower amount of RUs achieved for the third injection of mini-FH indicates that the C3b surface was not completely regenerated after being exposed to higher C5 concentrations. (C) As in panel B, but analytes were injected in the following sequence: mini-FH at 140 nM, C5 at 110 nM mixed with both eculizumab at 1.7 µM and coversin at 1.7 µM (C5/eculizumab /coversin), C5/eculizumab (110 nM:1.7 µM), C5/coversin (110 nM:1.7 µM), and C5 alone at 110 nM. The C5 inhibitors themselves did not bind to the sensor chip (not depicted). Ecu, eculizumab.

SPR analysis of C5 binding to C3b. (A) Binding of C5 and mini-FH to C3b immobilized on a carboxymethyldextran-coated sensor chip by amine coupling (800 RUs). Mini-FH at a concentration of 140 nM or C5 at 100 nM was applied to the C3b surface (reference-subtracted responses are shown throughout). (B) C5 binding to “physiologically,” convertase-immobilized C3b. C3 convertases were assembled onto the amine coupled C3b sensor chip followed by flow of C3, which becomes activated in situ and binds covalently. According to this procedure, another 900 RUs of C3b were immobilized in a physiological manner via the convertase onto the 800 RUs of amine-coupled C3b. Mini-FH was assayed at 1.5 µM in 2 consecutive injections (2 overlaid dark blue curves), followed by C5 at 1.1, 0.6, 0.3, and 0.1 µM (black curves) and then another injection of mini-FH at 1.5 µM (cyan). The lower amount of RUs achieved for the third injection of mini-FH indicates that the C3b surface was not completely regenerated after being exposed to higher C5 concentrations. (C) As in panel B, but analytes were injected in the following sequence: mini-FH at 140 nM, C5 at 110 nM mixed with both eculizumab at 1.7 µM and coversin at 1.7 µM (C5/eculizumab /coversin), C5/eculizumab (110 nM:1.7 µM), C5/coversin (110 nM:1.7 µM), and C5 alone at 110 nM. The C5 inhibitors themselves did not bind to the sensor chip (not depicted). Ecu, eculizumab.

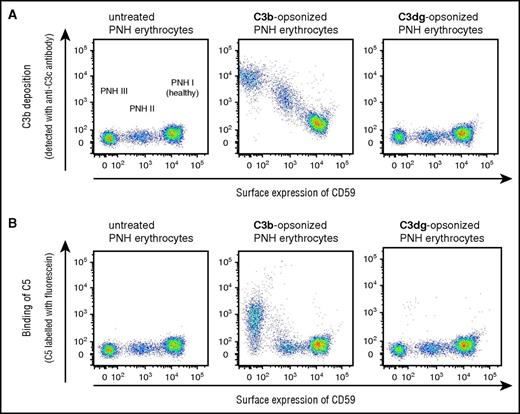

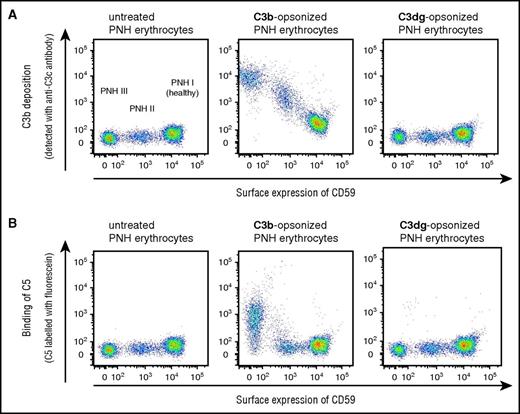

To verify that C3b clusters are sufficient to recruit C5 in a physiological context, we probed untreated, C3b-loaded and C3dg-loaded PNH-RBCs for binding of C5 (Figure 4). Only C3b-loaded cells were able to recruit C5. The levels of C5 binding correlated directly with the levels of deposited C3b on the PNH-RBCs, thus cross-validating the findings from the SPR experiment.

FACS analysis of C5 binding to PNH-RBCs loaded with C3b or C3dg. PNH-PBCs were loaded with C3b in human factor I–depleted serum under combined C5 inhibition (with eculizumab and coversin) to allow for efficient C3b opsonization without lysis. A portion of the C3b loaded cells were exposed to factor I to allow for processing of the surface-bound C3b to C3dg. (A) Correlation of C3b deposition levels with PNH subtype. Detection of expression levels of CD59 (x-axis) allows classification of PNH-RBCs in type I (normal CD59 levels), type II (reduced level), and type III erythrocytes (absence of CD59). C3b deposition (y-axis) is more pronounced for type III PNH-RBCs than for type II or type I. (B) Correlation of C5 binding with C3b surface levels. C5 binding on PNH-RBCs coincides with high C3b density (1 representative assay from 2 independent experiments is shown).

FACS analysis of C5 binding to PNH-RBCs loaded with C3b or C3dg. PNH-PBCs were loaded with C3b in human factor I–depleted serum under combined C5 inhibition (with eculizumab and coversin) to allow for efficient C3b opsonization without lysis. A portion of the C3b loaded cells were exposed to factor I to allow for processing of the surface-bound C3b to C3dg. (A) Correlation of C3b deposition levels with PNH subtype. Detection of expression levels of CD59 (x-axis) allows classification of PNH-RBCs in type I (normal CD59 levels), type II (reduced level), and type III erythrocytes (absence of CD59). C3b deposition (y-axis) is more pronounced for type III PNH-RBCs than for type II or type I. (B) Correlation of C5 binding with C3b surface levels. C5 binding on PNH-RBCs coincides with high C3b density (1 representative assay from 2 independent experiments is shown).

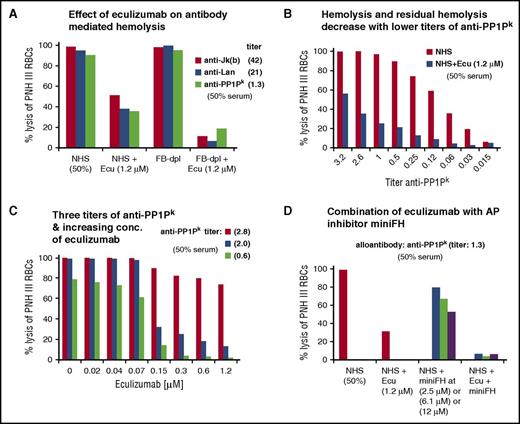

Residual lysis of eculizumab after forceful activation of the CP

In the CP assay using antibody-sensitized shRBCs (Figure 1A), we failed to detect any residual hemolysis under C5 inhibition. In the light of the above findings, this could be due to this assay being typically performed at low serum content, which is chosen particularly to avoid substantial contributions of the AP. We therefore hypothesized that strongly complement activating antibodies at high serum content (of 50%) would produce sufficiently dense C3b deposits to allow for residual activation of C5 in presence of the C5 inhibitor eculizumab.

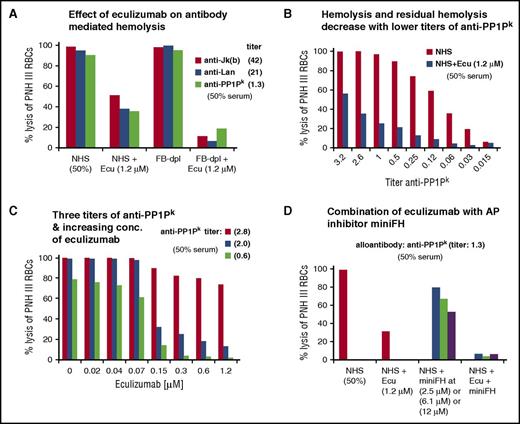

To stay within a human system, PNH-RBCs were used as a complement-sensitive host cell type to be preincubated with different alloantibodies (in EDTA-plasma), washed, and exposed to serum. Incubation of PNH-RBCs challenged with 3 different alloantibodies against blood group antigens resulted in nearly complete hemolysis of the complement sensitive type III PNH-RBCs in NHS (Figure 5A). Considering that the in vitro assay is performed at a serum content of 50%, the eculizumab concentration of 1.2 µM exceeds the expected C5 concentration in the assay (normal range in serum is 0.3 to 0.6 µM) at least fourfold. Disregarding this excess of eculizumab, substantial levels of hemolysis remained, indicating that residual TP activity under eculizumab also occurs after forceful activation of the CP.

Residual hemolysis of antibody-sensitized PNH erythrocytes in presence of eculizumab. (A) Residual TP activity under eculizumab after CP activation detected through hemolysis of PNH-RBCs. Three different alloantibodies were each incubated with erythrocytes from PNH patients (all of ABO blood group 0, positive for the antigens Jkb, Lan, and PP1Pk), washed and exposed to standardized NHS, standardized FB-dpl serum, or serum mixed with eculizumab. The final serum content was 50%, and the final eculizumab concentration was 1.2 µM. Erythrocytes from PNH patient D were used. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for the 2 other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients E and F, see supplemental Figure 6A-B). (B) Levels of hemolysis and residual hemolysis under eculizumab correlate with the concentration of anti-PP1Pk antibody used for sensitization. PNH-RBCs were incubated with anti-PP1Pk alloantibody at different titers, washed, and then exposed to NHS or NHS supplemented with eculizumab. The final serum content was 50%. Erythrocytes from PNH patient F were used. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for the 2 other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients G and F with alloantibody anti-Jka and anti-Lan, see supplemental Figure 7). (C) Effect of increasing eculizumab concentrations on hemolysis of PNH-RBCs sensitized with different titers of alloantibody. Reactions were performed as in panel B. Anti-PP1Pk alloantibody and erythrocytes from PNH patient F were used. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for the 2 other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients C and F with alloantibody anti-Jra, see supplemental Figure 8). (D) Effect of combined complement inhibition by eculizumab and the alternative pathway inhibitor mini-FH (which specifically accelerates the natural decay of alternative pathway convertases but is a cofactor for factor I–mediated cleavage of all, classical/lectin and alternative pathway produced C3b molecules). Assay was performed as in panel B, with PNH-RBCs of patient F and anti-PP1Pk alloantibody. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients E and F and anti-Jkb alloantibody, see supplemental Figure 9). Ecu, eculizumab.

Residual hemolysis of antibody-sensitized PNH erythrocytes in presence of eculizumab. (A) Residual TP activity under eculizumab after CP activation detected through hemolysis of PNH-RBCs. Three different alloantibodies were each incubated with erythrocytes from PNH patients (all of ABO blood group 0, positive for the antigens Jkb, Lan, and PP1Pk), washed and exposed to standardized NHS, standardized FB-dpl serum, or serum mixed with eculizumab. The final serum content was 50%, and the final eculizumab concentration was 1.2 µM. Erythrocytes from PNH patient D were used. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for the 2 other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients E and F, see supplemental Figure 6A-B). (B) Levels of hemolysis and residual hemolysis under eculizumab correlate with the concentration of anti-PP1Pk antibody used for sensitization. PNH-RBCs were incubated with anti-PP1Pk alloantibody at different titers, washed, and then exposed to NHS or NHS supplemented with eculizumab. The final serum content was 50%. Erythrocytes from PNH patient F were used. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for the 2 other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients G and F with alloantibody anti-Jka and anti-Lan, see supplemental Figure 7). (C) Effect of increasing eculizumab concentrations on hemolysis of PNH-RBCs sensitized with different titers of alloantibody. Reactions were performed as in panel B. Anti-PP1Pk alloantibody and erythrocytes from PNH patient F were used. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for the 2 other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients C and F with alloantibody anti-Jra, see supplemental Figure 8). (D) Effect of combined complement inhibition by eculizumab and the alternative pathway inhibitor mini-FH (which specifically accelerates the natural decay of alternative pathway convertases but is a cofactor for factor I–mediated cleavage of all, classical/lectin and alternative pathway produced C3b molecules). Assay was performed as in panel B, with PNH-RBCs of patient F and anti-PP1Pk alloantibody. (Results from 1 out of 3 independent assays are shown; for other assays with erythrocytes from PNH patients E and F and anti-Jkb alloantibody, see supplemental Figure 9). Ecu, eculizumab.

To substantiate that hemolysis by the 3 alloantibodies is caused by the CP, we repeated the assay in FB-dpl serum, where AP activity is absent. As expected, depletion of factor B from serum had no measurable effect on overall alloantibody-mediated hemolysis. However, when FB-dpl serum was combined with eculizumab, substantially lower levels of hemolysis occurred. This indicates once more that AP-mediated amplification of C3b plays a role in producing the C3b densities that efficiently promote C5 activation.

The level of CP mediated hemolysis and residual hemolysis under C5 inhibition depends on the titer of alloantibody used, exhibiting a clear dose response relationship (Figure 5B). Using different titers, we gradually increased the concentration of eculizumab (Figure 5C). For all titers of alloantibody, hemolysis was reduced when the eculizumab concentration reached ∼0.15 µM, which corresponds to the expected C5 concentration in the assay of ∼0.15 to 0.3 µM. In samples with low alloantibody titers (hence moderate activation), addition of eculizumab nearly completely prevented hemolysis. However, in samples with powerful CP activation through higher alloantibody titers, eculizumab failed to provide sufficient protection and substantial levels of hemolysis remained.

To further investigate the role of the AP in producing high C3b densities that promote residual TP activity under C5 inhibition, we performed the assay also in presence of the AP inhibitor mini-FH. Mini-FH at 2.5 µM, which exceeds the amount of mini-FH needed to inhibit the AP 10-fold, interfered to a minor extent with CP mediated hemolysis of PNH-RBCs (Figure 5D). However, when eculizumab was combined with mini-FH, the levels of residual TP activity were reduced similarly to the combination of eculizumab with FB-dpl serum.

These experiments show that residual TP activity under C5 inhibition also occurs after activation of the CP and directly correlates with the strength of the complement activation signal, since higher titers of alloantibody result in higher levels of residual hemolysis.

Discussion

PNH and aHUS patients profit considerably from eculizumab blocking TP activation. However, several clinical reports show that TP activation products can still be detected ex vivo in analytical assays in patients that receive sufficient doses of eculizumab to completely block C5 activation.33,34 This suggests that despite the presence of sufficient eculizumab levels, some C5 activation must occur in these patients. Therefore, we investigated to what extent eculizumab and other C5 inhibitors block TP activation in different ex vivo assays.

In AP-mediated lysis assays of rRBCs substantial levels of residual TP activity remained even under excess amounts of 3 different C5 inhibitors tested (eculizumab, coversin, and commercial anti-C5) (Figure 1C). In a common CP assay with sensitized shRBCs and low serum content, eculizumab as well as coversin completely blocked hemolysis (Figure 1A). In contrast, in a sensitive assay using PNH-RBCs and forcefully activating alloantibodies (Figure 5), residual hemolysis was detected in the presence of eculizumab. This implies that residual C5 activity is a more general effect of C5 inhibition and that traditional clinical in vitro assays in diluted serum may not necessarily pick up residual TP activity in vivo. Residual TP activity under eculizumab was also observed for other surfaces that are susceptible to complement attack, like E coli or PNH-RBCs (Figure 2A; supplemental Figure 3).

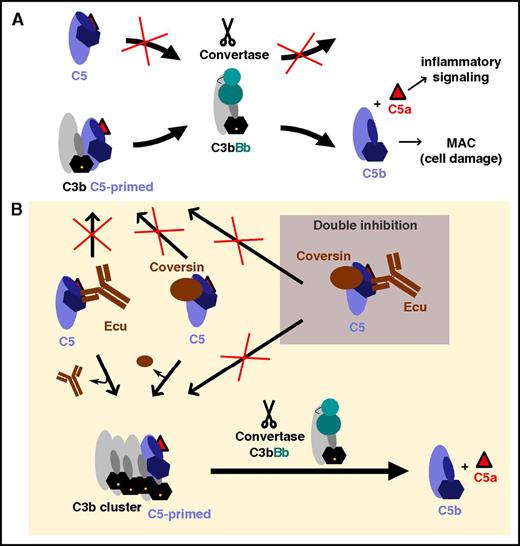

Such residual C5 activity under eculizumab treatment may actually be beneficial in terms of allowing low levels of pathogen lysis but detrimental when complement activation is overwhelming. While residual TP activity was pronounced on E coli cells, residual lysis of PNH-RBCs was noticeable, but at a lower level (Figure 2A). Thus, the level of residual TP activity seems to correlate with the strength of the complement activation trigger. This is consistent with foreign cells such as rRBCs or bacteria that result in stronger complement activation than non–alloantibody-challenged PNH host cells. That the strength of complement activation directly correlated with the levels of residual hemolysis was further corroborated by the dose-dependent residual TP activity when AP activity was increased through increasing the Mg-ion concentration (Figure 2B) or when CP activity was increased through higher alloantibody titers in 50% serum (Figure 5B-C). It was demonstrated that C5 activation depends on the density of surface-deposited C3b clusters.20,53,54 An artificial increase of C3b density on PNH-RBCs by a preloading step indeed correlates with higher levels of residual hemolysis (Figure 2C). When AP-mediated hemolysis is blocked more proximal in the cascade by applying mini-FH, protection from lysis is achieved (Figures 1D-E and 2B-C). Also, inhibition of the AP amplification loop (with mini-FH or via depletion of factor B) after initiating the CP with alloantibodies efficiently reduces residual TP activity (Figure 5A,D). This stresses the physiological role of the AP in producing high C3b densities that capture C5 in the primed, convertase-sensitive conformation to promote TP activation (Figure 6). Apart from combining a C5 inhibitor with a proximal cascade inhibitor (eg, mini-FH), the simultaneous application of 2 distinct C5 inhibitors, such as eculizumab and coversin, also potentiates the single inhibitory effects and nearly completely protects from hemolysis (Figures 1B-E, 2B-C, and 5C). As proposed by Jore et al,13 we speculate that eculizumab and coversin prevent the conformational transition of C5 (upon C3b binding) into the primed C5 state, which is susceptible to activation by the C5 convertase. However, under forceful complement activation, the densely packed C3b molecules compete efficiently with a C5 inhibitor for recruiting C5 in the primed conformation. In contrast, simultaneous C5 inhibition by eculizumab and coversin rigorously stabilizes the unproductive C5 conformation and thus prevents C5 activation even in the presence of high C3b density (Figure 6). The SPR data support this notion by demonstrating that double inhibition of C5 does reduce (but does not completely abolish) binding of C5 to C3b clusters (Figure 3C). Hence, the mechanism of C5 inhibition likely entails the stabilization of the C5 conformation that is not susceptible to convertase action in addition to potential contributions from steric inhibition.

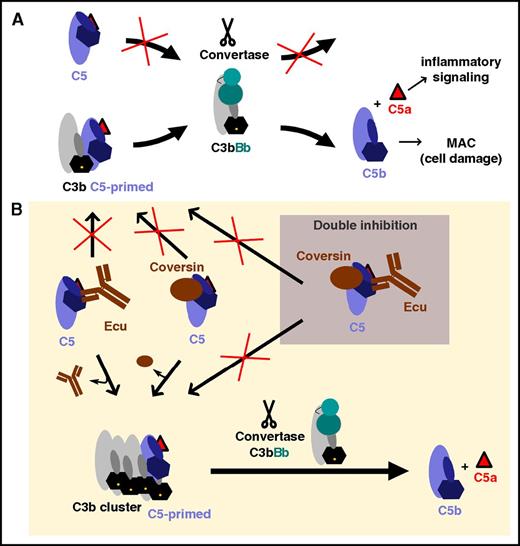

Hypothetical model of C5 activation and inhibition. (A) Adaptation of a model of C5 activation proposed by Jore et al.13 The scissile bond in C5 (located near the anaphylatoxin domain, C5a, which is depicted as a red triangle) is not readily accessible in free C5 for proteolytic activation by the convertase C3bBb. When C5 binds to C3b molecules, it undergoes a conformational change (a “priming event”) that renders the scissile bond accessible for proteolytic activation by a nearby convertase. (B) C5 inhibitors stabilize the unproductive C5 conformation, thus hindering the conformational priming event and, thus, the proteolytic activation of C5. However, surfaces bearing densely packed C3b molecules can compete (to some extent) with C5 inhibitors for C5 priming (ie, binding and conformational reorientation), resulting in a residual C5 activation level. Simultaneous inhibition with 2 orthogonal C5 inhibitors more effectively stabilizes the unproductive C5 conformation and prevents activation by the convertase even in presence of high C3b densities. Ecu, eculizumab; MAC, membrane attack complex.

Hypothetical model of C5 activation and inhibition. (A) Adaptation of a model of C5 activation proposed by Jore et al.13 The scissile bond in C5 (located near the anaphylatoxin domain, C5a, which is depicted as a red triangle) is not readily accessible in free C5 for proteolytic activation by the convertase C3bBb. When C5 binds to C3b molecules, it undergoes a conformational change (a “priming event”) that renders the scissile bond accessible for proteolytic activation by a nearby convertase. (B) C5 inhibitors stabilize the unproductive C5 conformation, thus hindering the conformational priming event and, thus, the proteolytic activation of C5. However, surfaces bearing densely packed C3b molecules can compete (to some extent) with C5 inhibitors for C5 priming (ie, binding and conformational reorientation), resulting in a residual C5 activation level. Simultaneous inhibition with 2 orthogonal C5 inhibitors more effectively stabilizes the unproductive C5 conformation and prevents activation by the convertase even in presence of high C3b densities. Ecu, eculizumab; MAC, membrane attack complex.

Although it has to be emphasized that the in vitro data may not fully represent the clinical status in vivo, these findings nevertheless have several clinical implications. While in general terms eculizumab efficiently inhibits TP activation in PNH and aHUS patients, in clinical situations with strong complement activation, residual TP activity may exist even with surplus amounts of eculizumab.55 A case of eculizumab-refectory hemolysis56 indicated that the prevention of intravascular hemolysis due to erythrocyte alloantibodies may be inefficient. Our in vitro data show that eculizumab reduces hemolysis levels after alloantibody challenge but that the level of benefit depends on how forcefully the alloantibody activates complement, thus depending on the alloantibody titer and subtype as well as prevalence of its epitope. Another clinical example is an aHUS patient who received a prophylactic eculizumab treatment of kidney transplantation.35 Despite analytical ex vivo monitoring showing absence of C5 functional activity, disease exacerbation was evident (C3 decreased, platelets dropped, lactate dehydrogenase increase), indicating that due to the underlying aHUS pathology and the surgical trauma, which activates complement, TP activation could not be totally suppressed. However, residual TP activity likely inflicts less lytic damage to (nucleated) endothelial cells relative to erythrocytes, which are especially susceptible to MAC.57 Moreover, PNH patients under steady-state eculizumab therapy regularly show signs of low-level intravascular hemolysis,58 which worsens with the occurrence of complement triggers like infections or surgery. An incomplete TP block provides a rationale for this phenomenon.

In conjunction with our data, the clinical examples emphasize that C5 inhibition is not absolute and depends on the clinical context. More powerful complement cascade triggers produce higher C3b densities in vivo, which correlate with the level of residual TP activity and thus may limit the therapeutic benefit of eculizumab. The mechanistic insight on residual TP activity in the presence of high C3b density also explains why early administration of eculizumab usually results in a more substantial clinical response, since early C5 inhibition prevents subsequent cell damage that leads to further complement activation. Contrary to insufficient dosing of eculizumab (eg, due to a higher distribution volume during pregnancy), which can be addressed by increasing the dose, our data indicate that even excess amounts of eculizumab cannot prevent residual C5 activity in situations of strong complement activation. In such situations, any further increase of eculizumab plasma concentrations above the levels of C5 neutralization may have little benefit. This may be of particular concern when clinical diagnostic ex vivo assays show maximal blockage of the C5 activity but TP activation products are still detectable in a patient’s blood due to residual C5 activity under eculizumab treatment during strong complement activation. Since the described suboptimal responses to eculizumab often resolve uneventfully, future clinical studies may assess if and at what level of residual TP activity a patient may benefit from additional complement blockade.

Interesting future concepts to circumvent such residual activity could be to block more proximal in the complement cascade or to simultaneously employ different C5 inhibitors, for example eculizumab and PAS-coversin. Such strategies may be beneficial when applications of therapeutic doses of eculizumab fail to result in a reasonable clinical response in situations that are known to produce strong complement activation, such as surgery, organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, acute transfusion reactions, or infections.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (SCHM 3018/2-1) (C.Q.S.), National Institutes of Health, National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI030040 and AI068730), and the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (602699 DIREKT) (D.R. and J.D.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.Q.S., M.A., I.v.Z., and M.J.H. conceived the study; C.Q.S., M.J.H., and M.A. performed the experiments; H.S., J.D.L., D.R., C.W., and B.H. advised on experimental design and data analysis; N.K., A.S., C.Q.S., and M.J.H. prepared the protein reagents; all authors contributed to the discussion of the data; the manuscript was written by C.Q.S., M.J.H., I.v.Z., and M.A.; and all authors critically revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.Q.S., D.R., and J.D.L. are inventors of a patent application that describes the use of mini-FH for therapeutic applications. J.D.L. is the founder of Amyndas Pharmaceuticals, which develops complement therapeutics. A.S. is founder of XL-protein, the company that develops and commercializes PASylation technology. B.H., C.Q.S., and H.S. received honoraria for speaking at symposia organized by Alexion Pharmaceuticals. H.S. and B.H. served on an advisory committee for and received research funding from Alexion Pharmaceuticals. H.S. served on an advisory committee for Ra Pharmaceuticals and Alnylam. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for D.R. is Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.

Correspondence: Christoph Q. Schmidt, Institute of Pharmacology of Natural Products and Clinical Pharmacology, Ulm University, Helmholtzstr 20, D-89081 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: christoph.schmidt@uni-ulm.de; or Markus Anliker, Institute of Clinical Transfusion Medicine and Immunogenetics Ulm, University of Ulm and German Red Cross Blood Service Baden-Württemberg–Hessen, Helmholtzstr 10, 89081 Ulm, Germany; e-mail: m.anliker@blutspende.de.

References

Author notes

M.A. and C.Q.S. contributed equally to this study.

![Figure 1. Different C5 inhibitors reveal residual TP activity on foreign activating cells. (A) CP-mediated lysis of shRBCs. Hemolysin-treated shRBCs were mixed with 5% serum in the presence of specific inhibitors. Released hemoglobin was measured as a marker of hemolysis (the average of 3 independent assays with standard deviation [SD] is shown). (B) AP-mediated lysis of rabbit erythrocytes. Rabbit erythrocytes were incubated in 25% human serum in presence of inhibitors or controls (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (C) Different combinations of C5 inhibitors protect rRBCs. As in panel B, but eculizumab and another commercial anti-C5 antibody (clone: 046-10.2.2) were used at concentrations that substantially exceed the typical C5 concentration of the serum dilution in this assay (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (D-E) TP activity of serum from PNH patients on eculizumab. rRBCs were incubated in 25% human serum derived from 2 PNH patients (#A and #B) on eculizumab in absence or presence of additional complement inhibitors as indicated (average of 2 independent assays with SD is shown). (F) Determination of free C5 levels through sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using eculizumab as capture antibody and a polyclonal anti-C5 as a detection antibody. Eculizumab deposited on the microtiter plate captures free C5 from NHS, but not when NHS has been premixed with 0.5 µM eculizumab. No free C5 was captured from patient serum or patient serum that had been diluted 1:1 (1-in-2) with NHS (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown; the NHS/eculizumab mixture [negative control] was only assayed twice). Ecu, eculizumab; PAS-Cov., PASylated Coversin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PBSE, PBS supplemented with EDTA (to 5 mM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/8/10.1182_blood-2016-08-732800/4/m_blood732800f1.jpeg?Expires=1767760931&Signature=CsChfVfFqpL4cr5mret5RSuO2bwjzYc8x98JSFjepJ0R1afoC2kRNpUsnfbjbKbcMetG72xp3NtkraK7pxwbGr50j6KZqnoe7mTvoZZS-IH99YehAsnfvhwLo-STjzeI5-qq6JdsOMcrJaZChFgSvKS9xvTdbOK7Fa3WG4CZq32jrCSsGaOnnJCDhUYTmArdWNGYyJ1hs6K0TFma88f5SFrqeTAwVhu4hZEI8~rUHlwEWmHpimWKTO6GZY9--uNd1VCpCiMdyCeTl5U2D12Q~Atyrwwxfq-mB5bGtZvso5Ft4TnDimX-ogd8C7Ys1MmbksSoyDyd2flOggvFhijenA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 1. Different C5 inhibitors reveal residual TP activity on foreign activating cells. (A) CP-mediated lysis of shRBCs. Hemolysin-treated shRBCs were mixed with 5% serum in the presence of specific inhibitors. Released hemoglobin was measured as a marker of hemolysis (the average of 3 independent assays with standard deviation [SD] is shown). (B) AP-mediated lysis of rabbit erythrocytes. Rabbit erythrocytes were incubated in 25% human serum in presence of inhibitors or controls (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (C) Different combinations of C5 inhibitors protect rRBCs. As in panel B, but eculizumab and another commercial anti-C5 antibody (clone: 046-10.2.2) were used at concentrations that substantially exceed the typical C5 concentration of the serum dilution in this assay (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown). (D-E) TP activity of serum from PNH patients on eculizumab. rRBCs were incubated in 25% human serum derived from 2 PNH patients (#A and #B) on eculizumab in absence or presence of additional complement inhibitors as indicated (average of 2 independent assays with SD is shown). (F) Determination of free C5 levels through sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using eculizumab as capture antibody and a polyclonal anti-C5 as a detection antibody. Eculizumab deposited on the microtiter plate captures free C5 from NHS, but not when NHS has been premixed with 0.5 µM eculizumab. No free C5 was captured from patient serum or patient serum that had been diluted 1:1 (1-in-2) with NHS (average of 3 independent assays with SD is shown; the NHS/eculizumab mixture [negative control] was only assayed twice). Ecu, eculizumab; PAS-Cov., PASylated Coversin; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PBSE, PBS supplemented with EDTA (to 5 mM).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/129/8/10.1182_blood-2016-08-732800/4/m_blood732800f1.jpeg?Expires=1767760932&Signature=WYjPrbi-h0qe2weDg5S6CYzF9oh6Y3M8WCcctvZZutCBFnk2DzUZx4Yi~59WdPzrIBiaOEqTtefg6d2KYqiUNPFir8n~E-B0IhIhQ-oP2yQsRlzGXg9CR1opolBXv-p8Wcyc~ue9s0lrN~taGzcmYiSum7Ip3MyGm3~C7kO6FXthELbizSaOSMxkXiiH~VnWx0NLuwlicQzhMAEAMvnrTWd--ytaWzGMC6VyZbwfyMPQpneBIXm4lE1NQDzgLcoNLDgwOTpb1ua2-SlEk78Pb62XxlGHCSdyWibmno8Ac9zyPorV1GGyivldkWYPx6PKbcUZC0522NkP0~3nF84Zcg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)