In this issue of Blood, Crump et al provide data on 636 refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) patients.1 In a retrospective analysis of a subset of subjects extracted from 2 observational cohorts and 2 randomized clinical trials, the authors describe outcomes in this patient population.2-6 The authors report a pooled response rate of 26% to the subsequent line of therapy. Although we acknowledge the useful findings of this study, we are cautious in considering this retrospectively defined cohort as a “benchmark” for prospective trials in refractory DLBCL.

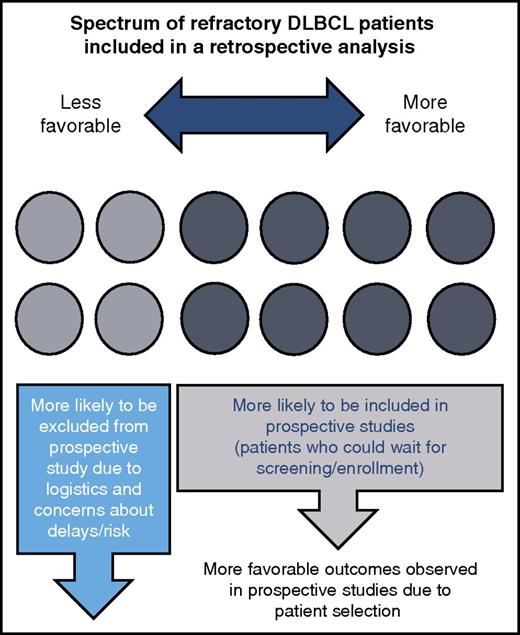

The refractory DLBCL population contains a wide spectrum of patients who are not all represented in prospective studies. A subset of patients with less favorable features are included in retrospective analyses, but not in prospective trials for reasons such as symptomatic disease that requires expedited treatment and abnormal laboratory values that deem patients ineligible for clinical trials. Therefore, prospective trials conducted in refractory DLBCL patients should be interpreted cautiously in comparison with retrospective data.

The refractory DLBCL population contains a wide spectrum of patients who are not all represented in prospective studies. A subset of patients with less favorable features are included in retrospective analyses, but not in prospective trials for reasons such as symptomatic disease that requires expedited treatment and abnormal laboratory values that deem patients ineligible for clinical trials. Therefore, prospective trials conducted in refractory DLBCL patients should be interpreted cautiously in comparison with retrospective data.

Retrospective studies often include patients who are very different from those enrolled in prospective trials. In this study, the authors define refractory as progressive disease or stable disease as best response after >4 cycles of first-line or 2 cycles of later-line treatment, or relapse ≤12 months after autologous stem cell transplant. The definitions of refractory vary as do eligibility criteria for clinical trials. The discrepancy is evident in the heterogeneous group included in this study: the response rate of patients after being refractory to second- or later-line treatment was 20% to 21% in the observational cohorts and 40% in one of the randomized clinical trials.1 Furthermore, subjects, including those who are doing well or especially poorly, can be lost to follow-up and therefore excluded based on missing data from retrospective analyses.

Our recent experience in clinic highlights these distinctions. We saw a patient with refractory DLBCL whose disease has been quite challenging to control. After initially responding to first-line therapy, he progressed while on second-line treatment, and traveled 2 hours to our academic center in hopes of enrolling in a clinical trial with a novel agent. He agreed to join a phase 1 trial, but unfortunately his screening laboratory studies and performance status (in part reflecting the extent and aggressiveness of disease) were outside the eligibility parameters, excluding him from trial participation. Other patients are not well enough to travel to research centers to discuss interventional clinical trials, and some are unable to leave the hospital due to symptoms from their disease.

The absence of these subjects with unfavorable disease from a prospective clinical trial will result in a study population having, as a whole, more favorable characteristics likely associated with a better outcome overall (see figure). However, if we now reported a retrospective analysis of all of our refractory DLBCL patients (or findings from a similar database), the patient described above would be included. A comparison of the 2 groups would be influenced by the fact that this patient (and others) with adverse characteristics would be included in the retrospective cohort, but absent from the prospective study. Therefore, if we went on to compare outcomes of patients treated in a new prospective trial of a novel treatment regimen with those included in our retrospective analysis, the comparison would be of apples vs apples plus oranges. Any use of these data as a yardstick for future single-arm prospective studies of new treatments must be evaluated in this context. When reviewing these findings alongside the results generated in unrelated studies of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies, which currently have the potential for significant selection biases, one must be careful in assuming similar results will be achieved in an unselected lymphoma population.

The study published by Crump et al is the largest data set reporting on the refractory DLBCL population. Although the patients were heterogeneous with refractory status occurring at various points along the disease course, the study combines the best available information to estimate response rates and survival in this group in 2 well-established observational cohorts and 2 of the largest clinical trials conducted in refractory DLBCL. The median overall survival of 6.3 months is similar to reports with smaller numbers of patients, particularly in those refractory to second-line therapy.7-9 Further efforts through multiple centers, such as the Lymphoma Epidemiology of Outcomes cohort study, will provide additional robust observational information on DLBCL and other lymphoma subtypes.

We are a bit heartened by the finding that 20% of refractory DLBCL patients were alive at 2 years. This is an encouraging statistic for admittedly just a subset of patients. It is unclear whether this represents the presence of a group of patients with relatively favorable disease or the potential value of certain specific approaches in the refractory disease setting. This information highlights that novel treatment strategies likely need to provide even better long-term survival results to be considered as major advances in this setting. Finally, Crump and colleagues remind us that despite the fact that most patients with DLBCL can be cured with standard therapies, there is more work to be done through translational research and clinical trials of novel agents. New approaches being tested in the laboratory and the clinic are exciting. However, they need to be assessed not through hope or hype, but through rigorous comparative studies, including long-term follow up.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.C.R. provided consulting advice for Juno. J.P.L. provided consulting advice for or has a Data and Safety Monitoring Board membership with Regeneron, AbbVie, Sutro, Biotest, Gilead, Celgene, Sunesis, Juno, Kite, Pfizer, Bayer, Roche, United Therapeutics, and BMS.