Key Points

Absence of RUNX1C in knock-in adult mice causes defective megakaryopoiesis and thrombocytopenia.

Unlike total RUNX1 deficiency absence of RUNX1C does not alter megakaryocyte maturation but increases apoptosis in megakaryocyte progenitors.

Abstract

RUNX1 is crucial for the regulation of megakaryocyte specification, maturation, and thrombopoiesis. Runx1 possesses 2 promoters: the distal P1 and proximal P2 promoters. The major protein isoforms generated by P1 and P2 are RUNX1C and RUNX1B, respectively, which differ solely in their N-terminal amino acid sequences. RUNX1C is the most abundantly expressed isoform in adult hematopoiesis, present in all RUNX1-expressing populations, including the cKit+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. RUNX1B expression is more restricted, being highly expressed in the megakaryocyte lineage but downregulated during erythropoiesis. We generated a Runx1 P1 knock-in of RUNX1B, termed P1-MRIPV. This mouse line lacks RUNX1C expression but has normal total RUNX1 levels, solely comprising RUNX1B. Using this mouse line, we establish a specific requirement for the P1-RUNX1C isoform in megakaryopoiesis, which cannot be entirely compensated for by RUNX1B overexpression. P1 knock-in megakaryocyte progenitors have reduced proliferative capacity and undergo increased cell death, resulting in thrombocytopenia. P1 knock-in premegakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors demonstrate an erythroid-specification bias, evident from increased erythroid colony-forming ability and decreased megakaryocyte output. At a transcriptional level, multiple erythroid-specific genes are upregulated and megakaryocyte-specific transcripts are downregulated. In addition, proapoptotic pathways are activated in P1 knock-in premegakaryocyte/erythroid progenitors, presumably accounting for the increased cell death in the megakaryocyte progenitor compartment. Unlike in the conditional adult Runx1 null models, megakaryocytic maturation is not affected in the P1 knock-in mice, suggesting that RUNX1B can regulate endomitosis and thrombopoiesis. Therefore, despite the high degree of structural similarity, RUNX1B and RUNX1C isoforms have distinct and specific roles in adult megakaryopoiesis.

Introduction

The core binding factor (CBF) transcription factor (TF) RUNX1/AML1 is crucial for the establishment of adult hematopoiesis, regulating various hematopoietic lineage cell fate decisions and ensuring the correct maturation of restricted progenitors to terminally differentiated blood cells.1-8 RUNX1 is broadly expressed throughout adult hematopoiesis, and its deletion impacts a broad spectrum of blood lineages in mice.9,10 For example, Mx1-Cre–directed Runx1 deletion in adult hematopoietic progenitors results in a mild myeloproliferative disorder and thrombocytopenia.5,6 The principal cause of thrombocytopenia in RUNX1-deficient animals is impaired megakaryocyte maturation; abrogation of RUNX1 activity yields small immature megakaryocytes with reduced polyploidization and megakaryocyte marker expression.5,6 This mirrors the defective platelet-formation phenotype observed in patients with familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia, a rare autosomal dominant disorder usually caused by germ line heterozygous inactivating mutations or deletions in RUNX1.11,12 RUNX1 target genes deregulated in familial platelet disorder with predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia megakaryocytes, and therefore proposed to be responsible for these defects in platelet production, include the thrombopoietin receptor MPL, 12-lipoxygenase (ALOX12) and the myosin proteins MYL9, MYH9, and MYH10.13-15 RUNX1 has also recently been demonstrated to mediate megakaryocytic (Mk) specification from bipotential Mk/erythroid (Mk/Ery) progenitors, through direct repression of the pro-Ery TF KLF1, thus tipping the balance in favor of the pro-Mk FLI1,16 a factor with which RUNX1 also interacts to mediate Mk differentiation.17 It is therefore clear that RUNX1 regulates megakaryopoiesis through multiple mechanisms.

All vertebrate Runx loci possess 2 alternate promoters: a distal P1 promoter and a proximal P2 promoter.18,19 In the case of RUNX1, the major protein products from the P1 and P2 promoters are the RUNX1C and RUNX1B isoforms, respectively, which differ solely in their N-terminal amino acid sequences: RUNX1B begins with MRIPV, whereas RUNX1C is 14 amino acids longer and begins with MASDS.20,21 Another key difference between the Runx1 promoters is the timing and localization of their expression; although P2 activity corresponds with the onset of embryonic definitive hematopoiesis, a switch to P1-dominated Runx1 expression occurs from the fetal liver stage and into adult bone marrow (BM) hematopoiesis.22,23 We recently undertook a detailed characterization of Runx1 promoter activity in adult hematopoiesis using a dual reporter mouse model to isolate highly purified hematopoietic subsets on the basis of Runx1P1 and/or P2 activity.24 We confirmed that P1 is indeed the dominant promoter in adult hematopoiesis, active in all Runx1-expressing subsets, whereas P2 activity is largely restricted to prolymphoid, granulocyte/macrophage, and Mk progenitor subsets but conspicuously absent from Ery-restricted progenitors. Given the preeminence of P1 activity, we also investigated the impact of its absence on adult hematopoiesis using a Runx1P1-GFP knock-in mouse line. Unlike the total RUNX1 knockout, deletion of P1-directed RUNX1C expression was not lethal, but resulted in numerous multilineage hematopoietic defects in adults,24 including mild thrombocytopenia, suggesting a partial recapitulation of the Mk lineage defects associated with total RUNX1 deficiency in this lineage. We therefore decided to pursue a detailed investigation of the impact of altered RUNX1 isoform expression, in particular RUNX1C-deficiency, on Mk/Ery lineage specification.

For this, alongside the Runx1P1-GFP reporter mouse model, we also developed and used a novel mouse line (P1-MRIPV) in which the RUNX1C-specific N-terminal amino acid sequence (MASDSIFESFPSYPQCFMR) was replaced by MRIPV, the P2-driven RUNX1B-specific amino acids. The P1-MRIPV mouse line therefore lacks RUNX1C expression but has normal total RUNX1 levels, due entirely to RUNX1B. Using these lines, we observed a bias in Mk/Ery progenitors toward Ery specification and away from megakaryopoiesis in the absence of RUNX1C, with or without RUNX1B compensation, an effect similar to that observed upon depleting total RUNX1 in hematopoietic progenitors.16 We did not, however, observe any impact on Mk maturation, unlike in total RUNX1-deficient mice.5,6 The defect in megakaryopoiesis in P1 knock-in mice was instead linked to reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis in the megakaryocyte progenitor (MkP) compartment. Altogether, this suggests that the roles of the different RUNX1 isoforms in Mk specification and maturation may be uncoupled.

Methods

Mice

P1-GFP mice have previously been described.22 Generation of the P1-MRIPV embryonic stem cells and mouse line are detailed in the supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site. All animal work was performed under regulations governed by UK Home Office Legislation under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and was approved by the Animal Welfare and Ethics Review Body of the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute. Details of animal husbandry and tissue collection are listed in the supplemental Methods.

FACS

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and sorting of Mk/Ery hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) was performed as described.24 Details of flow cytometry reagents are listed in supplemental Table 1 and details of combinations used for each analysis are listed in supplemental Table 2. Associated FACS protocols are detailed in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

Flow cytometry plots display mean values of each indicated population. Unless otherwise stated, a sample size of n = 1 refers to tissues collected from 1 adult mouse. Unless otherwise indicated, data were evaluated using an ordinary 2-way analysis of variance and expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Additional methods are found in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Mk/Ery specification is skewed in the absence of RUNX1C

It has been established that the distal P1 promoter dominates in terms of Runx1 transcriptional activity during adult hematopoiesis.23,24 We therefore used 2 Runx1P1 knock-in lines (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1) to investigate the effect of the absence of the RUNX1C isoform on adult hematopoietic lineage specification. The first line (previously described22 ) had GFP inserted downstream of the transcription start site of the distal P1 promoter, replacing the coding sequence of the Runx1c-specific exon 2 and eliminating further splicing to the third exon (supplemental Figure 1, P1-GFP allele). This line has the advantage of allowing fluorescence-mediated cell tracing of P1 activity. However, it also has the disadvantage that Runx1 expression is inevitably decreased because of Runx1 transcripts being produced solely from the proximal P2 locus. In contrast, in the second line, the distal locus remains intact with the exception of the RUNX1C-specific N-terminal MASDSIFESFPSYPQCFMR amino acid–encoding region being replaced with that of the RUNX1B-specific MRIPV amino acids, as confirmed by sequencing of Runx1P1 cDNA (Figure 1A; supplemental Figure 1B, P1-MRIPV allele). The P1-MRIPV line therefore maintains Runx1 expression from both promoters but produces RUNX1B only.

Mk/Ery specification is skewed in the absence of RUNX1C. (A) Schematic representations of the Runx1 WT (top) and P1-MRIPV (bottom) alleles. White bars, noncoding regions; black bars, common coding regions; colored (red or blue) bars, unique coding regions. mRNA, messenger RNA. (B-C) Peripheral blood parameters of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV mice as determined by Sysmex automated cell counting. (B) Red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet counts; (C) plateletcrit. (WT, N = 5; P1-MRIPV/+ and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV, N = 6). (D-F) Flow cytometric analysis of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV BM Mk/Ery progenitor (PreMegE, MkP, PreCFUe, and CFUe) and LSK HSPC populations. (D) Representative FACS plots of Mk/Ery progenitors; (E) representative FACS plots of LSK HSPCs; (F) proportions of HSPCs as a percentage of total live BM cells; N = 6. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Mk/Ery specification is skewed in the absence of RUNX1C. (A) Schematic representations of the Runx1 WT (top) and P1-MRIPV (bottom) alleles. White bars, noncoding regions; black bars, common coding regions; colored (red or blue) bars, unique coding regions. mRNA, messenger RNA. (B-C) Peripheral blood parameters of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV mice as determined by Sysmex automated cell counting. (B) Red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet counts; (C) plateletcrit. (WT, N = 5; P1-MRIPV/+ and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV, N = 6). (D-F) Flow cytometric analysis of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV BM Mk/Ery progenitor (PreMegE, MkP, PreCFUe, and CFUe) and LSK HSPC populations. (D) Representative FACS plots of Mk/Ery progenitors; (E) representative FACS plots of LSK HSPCs; (F) proportions of HSPCs as a percentage of total live BM cells; N = 6. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001; ****P < .0001.

Having performed automated peripheral blood counts on wild-type (WT), P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV littermates, we established that although red and white blood cell counts were unaffected by the absence of RUNX1C in P1-MRIPV homozygotes, the platelet count and plateletcrit were modestly but significantly decreased (Figure 1B-C), suggesting impaired thrombopoiesis and/or megakaryopoiesis. This reflected a similar state to that observed in the P1-GFP/GFP mice24 and prompted us to investigate the impact of the absence of RUNX1C on the Mk lineage in greater detail. Although the total BM cellularity (supplemental Figure 1C-D) and the frequency of the total HSPC compartment were not significantly impacted (supplemental Figure 1E-F), the relative abundance of Lin− cKit+ Sca1− (LK) Mk/Ery progenitors was altered in both the P1 knock-in mouse lines. P1-GFP/GFP and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV mice had reduced immunophenotypic MkP (dark blue gate, LK CD16/32− CD150+ CD41+)25,26 fractions (Figure 1D,F; supplemental Figure 1G,I). By comparison, the premegakaryocyte/Ery progenitor (PreMegE; green gate, LK CD16/32− CD41− CD150+ endoglin−) and pre-Ery colony forming unit (PreCFUe, red gate, LK CD16/32− CD41− CD150+ endoglin+) compartments were expanded. Therefore deletion of RUNX1C appeared to result in an Ery-specification bias in the Mk/Ery BM progenitor fractions. This appeared to be resolved in the Ery lineage as maturation progressed, however, because there was no perturbation in the numbers of LK CD16/32− CD41− CD150− endoglin+ immunophenotypic Ery colony-forming units (CFUes, Figure 1D,F; supplemental Figure 1G,I) as well as the subsequent CD71high Ter119int proerythroblast, CD71high Ter119high FSChigh EryA, CD71high Ter119high FSClow EryB, and CD71low Ter119high FSClow EryC fractions24 (supplemental Figure 1J-K). We have previously demonstrated that the distal P1Runx1 promoter is highly expressed in BM Mk/Ery progenitors, although the proximal P2 promoter is also active in the megakaryocytic lineage.24 However, that the Ery bias is present in both P1 knock-in lines suggests it cannot be solely explained by reduced total Runx1 transcription as recently suggested.16

Interestingly, the recently described “megakaryocyte biased” HSC fraction (lineage-marker− Sca1+ cKit+ [LSK] CD34low CD150+ cKithigh)27 was significantly decreased in the P1-MRIPV heterozygotes and homozygotes, but not in the P1-GFP mice (Figure 1E-F; supplemental Figure 1H-I), whereas the more immature cKitlow HSC was expanded in both models. Unfractionated BM replated in hematopoietic colony-forming unit (CFU-C) assay media did not reveal significant differences in overall colony forming activity, with the exception of a slight increase in CFUe activity in the P1 knock-in mice24 (supplemental Figure 1L). However, there was no indication of a pro-Ery /anti-Mk bias at the HSC level because CFU-C activity was not perturbed in either P1-GFP or P1-MRIPV HSCs, with multilineage granulocyte/Ery/megakaryocyte/monocyte colonies dominating overall (supplemental Figure 1M-N). The reduction in cKithigh immunophenotypic HSCs may reflect RUNX1 directly impacting cKit expression28,29 or may alternatively indicate a subtle shift in Mk output downstream that we have been unable to detect at this level. Therefore, we proceeded to characterize the more mature LK progenitors.

Mk output is reduced in P1 knock-in progenitors

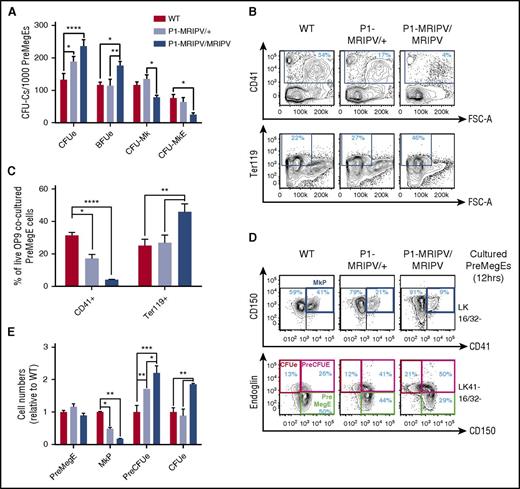

The observed impact on BM Mk/Ery progenitor numbers prompted us to ask whether the specific absence of RUNX1C affected Mk/Ery specification and differentiation. P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE cells had significantly increased CFUe and Ery burst-forming unit activity compared with WT and P1-MRIPV/+ cells (Figure 2A). In addition, CFU-Mk and bipotential Mk-Ery colony numbers were decreased, suggesting the pro-Ery differentiation bias observed in vivo is cell-autonomous in the PreMegE fraction. Furthermore, following OP9 coculture, P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE cells yielded significantly more Ter119+ Ery cells and fewer CD41+ megakaryocytes compared with their heterozygous and WT counterparts (Figure 2B-C).

Megakaryocytic output is reduced in P1 knock-in PreMegEs. (A) CFU-C activity of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE cells following culture in promyeloid methylcellulose medium (N = 4). (B-C) CD41 and Ter119 expression of OP9 cocultured PreMegE cells isolated on day 7. (B) Representative FACS plots; (C) quantification of CD41+ Mk and Ter119+ erythrocytes (N = 4). (D-E) Mk/Ery progenitor marker expression of PreMegEs following short-term (12 hours) culture in promyeloid liquid medium. (D) Representative FACS plots of PreMegE cells. (Top) CD150/CD41 expression of LK CD16/32− (LK 16/32−) progenitor cells. (Bottom) Endoglin/CD150 expression of LK CD41− CD16/32− (LK41− 16/32−) progenitors; (E) quantification of immunophenotypic PreMegEs, MkPs, PreCFUes, and CFUes relative to WT cultured cells (N = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. FSC-A, forward scatter–area.

Megakaryocytic output is reduced in P1 knock-in PreMegEs. (A) CFU-C activity of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE cells following culture in promyeloid methylcellulose medium (N = 4). (B-C) CD41 and Ter119 expression of OP9 cocultured PreMegE cells isolated on day 7. (B) Representative FACS plots; (C) quantification of CD41+ Mk and Ter119+ erythrocytes (N = 4). (D-E) Mk/Ery progenitor marker expression of PreMegEs following short-term (12 hours) culture in promyeloid liquid medium. (D) Representative FACS plots of PreMegE cells. (Top) CD150/CD41 expression of LK CD16/32− (LK 16/32−) progenitor cells. (Bottom) Endoglin/CD150 expression of LK CD41− CD16/32− (LK41− 16/32−) progenitors; (E) quantification of immunophenotypic PreMegEs, MkPs, PreCFUes, and CFUes relative to WT cultured cells (N = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. FSC-A, forward scatter–area.

In the P1-GFP homozygotes, we observed a similar decrease in CD41+ megakaryocyte output by the OP9-cocultured PreMegEs, but there was no significant accompanying increase in Ter119+ erythrocyte numbers (supplemental Figure 2B-C). In addition, CFU activity was not significantly perturbed in the P1-GFP/GFP PreMegEs (supplemental Figure 2A). Thus the phenotypes of the P1-MRIPV and P1-GFP Mk/Ery progenitors appear to differ significantly. A recent study indicated that total RUNX1 deficiency impairs Ery differentiation.30 We therefore postulated that the absence of RUNX1C and the reduction of total RUNX1 in the P1-GFP model (supplemental Figure 1Q) may result in conflicting phenotypes: a bias against or toward megakaryopoiesis, respectively. Indeed, we observed a substantial decrease in RUNX1 protein levels in P1-GFP/GFP BM (supplemental Figure 1Q), which appears to result in a compensatory upregulation in Runx1 transcription in MkPs (supplemental Figure 1P), whereas RUNX1 RNA and protein levels appeared normal in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV mice. We therefore focused further investigations on the P1-MRIPV model, which allowed us to analyze the impact of deleting the Runx1c isoform while maintaining total Runx1 expression (supplemental Figure 1O-Q).

To investigate whether the observed bias in favor of Ery differentiation in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegEs occurs primarily at the point of PreMegE commitment to either the megakaryocyte or Ery lineages, we traced PreMegE differentiation in vitro for up to 12 hours (Figure 2D-E; supplemental Figure 2D-E). We observed a reduction in phenotypic MkP output and an expansion of the PreCFUe in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV cultured PreMegEs from 6 hours, followed by expansion of the immunophenotypic CFUe (red gate) at 12 hours. Interestingly, the relative proportions of PreMegE cells were unaltered in WT and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV cultures, suggesting that their overall differentiation capacity was not impaired, but that Ery was favored over Mk specification by the absence of RUNX1C.

Deleting the Runx1 distal isoform does not affect megakaryocyte maturation

In addition to a recently characterized role in the repression of Ery specification,16 RUNX1 has a prominent role regulating Mk differentiation.5,31 To investigate whether the latter is also impaired in the absence of RUNX1C, we analyzed megakaryocytes in P1-MRIPV BM. In WT mice, CD41+ megakaryocytes accounted for approximately 11% of the total live cells (Figure 3A-B). We observed a moderate but significant reduction in the P1-MRIPV heterozygous and homozygous mice. This reduction in primary CD41+ megakaryocytes was substantially less severe than that observed for cultured megakaryocytes (Figure 2B). We decided to measure the plasma thrombopoietin levels and observed that they were unchanged in P1-MRIPV/+ and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV mice compared with their WT littermates (supplemental Figure 3A). This therefore suggests that P1-MRIPV progenitors possess an impaired intrinsic Mk specification, but that plasma thrombopoietin levels being maintained at normal levels has a partial compensatory effect in vivo.

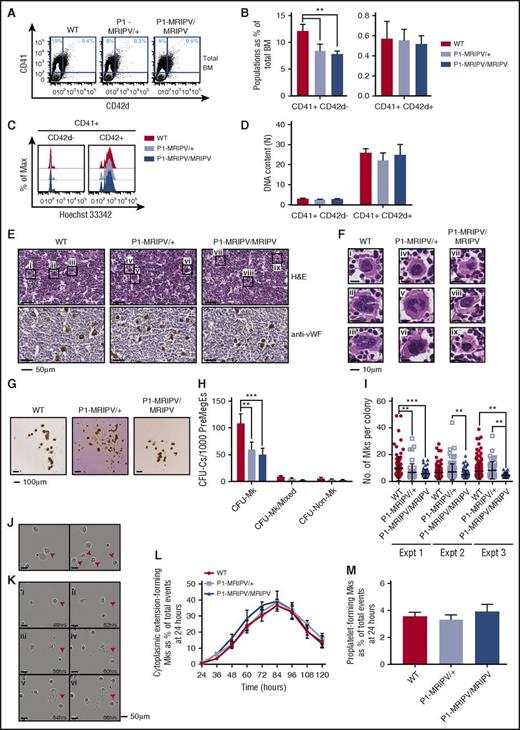

Deleting the Runx1 distal isoform does not affect megakaryocyte maturation. (A-D) FACS analysis of BM WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV megakaryocytes. (A) Representative FACS plots of CD41 and CD42d expression; (B) quantification of CD41+ CD42d−, and CD41+ CD42d+ megakaryocytes (N = 6). (C) Representative FACS plots of DNA content (Hoechst 33342 incorporation) of CD41+ CD42d− (left) and mature CD41+ CD42d+ (right) BM megakaryocytes. (D) Mean ploidy (DNA content) of CD41+ CD42d−, and CD42d+ BM megakaryocytes (N = 3). (E-F) Histological analysis of BM megakaryocytes. (E, top) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained BM sections. (Bottom) Anti-mouse von Willebrand factor (vWF)-stained BM sections. (F) Enlarged images of megakaryocytes i-ix as indicated in panel E. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown. (G-I) CFU-C activity of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE cells following culture in MegaCult medium. (G) Photographs of representative MegaCult colonies; (H) colony (CFU-C) numbers per 1000 PreMegEs (N = 5); (I) numbers of megakaryocytes per CFU-Mk colony from 3 representative independent experiments (mean ± standard deviation, Mann-Whitney U test). (J-M) Megakaryocyte differentiation in vitro captured by time lapse imaging. (J) Representative images of cytoplasmic extension-forming megakaryocytes (red arrowheads); (K) representative images of a proplatelet-forming megakaryocyte (red arrowheads) at 48 to 68 hours in culture. (L) Quantitation of cytoplasmic extension-forming megakaryocytes from 24 to 120 hours in culture, normalized to the total number of events (visible cells) at 24 hours; (M) quantitation of proplatelet-forming megakaryocytes from 24 to 120 hours normalized to the total number of events at 24 hours (N = 6). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. Expt, experiment.

Deleting the Runx1 distal isoform does not affect megakaryocyte maturation. (A-D) FACS analysis of BM WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV megakaryocytes. (A) Representative FACS plots of CD41 and CD42d expression; (B) quantification of CD41+ CD42d−, and CD41+ CD42d+ megakaryocytes (N = 6). (C) Representative FACS plots of DNA content (Hoechst 33342 incorporation) of CD41+ CD42d− (left) and mature CD41+ CD42d+ (right) BM megakaryocytes. (D) Mean ploidy (DNA content) of CD41+ CD42d−, and CD42d+ BM megakaryocytes (N = 3). (E-F) Histological analysis of BM megakaryocytes. (E, top) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained BM sections. (Bottom) Anti-mouse von Willebrand factor (vWF)-stained BM sections. (F) Enlarged images of megakaryocytes i-ix as indicated in panel E. Representative images from 3 independent experiments are shown. (G-I) CFU-C activity of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE cells following culture in MegaCult medium. (G) Photographs of representative MegaCult colonies; (H) colony (CFU-C) numbers per 1000 PreMegEs (N = 5); (I) numbers of megakaryocytes per CFU-Mk colony from 3 representative independent experiments (mean ± standard deviation, Mann-Whitney U test). (J-M) Megakaryocyte differentiation in vitro captured by time lapse imaging. (J) Representative images of cytoplasmic extension-forming megakaryocytes (red arrowheads); (K) representative images of a proplatelet-forming megakaryocyte (red arrowheads) at 48 to 68 hours in culture. (L) Quantitation of cytoplasmic extension-forming megakaryocytes from 24 to 120 hours in culture, normalized to the total number of events (visible cells) at 24 hours; (M) quantitation of proplatelet-forming megakaryocytes from 24 to 120 hours normalized to the total number of events at 24 hours (N = 6). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. Expt, experiment.

We also observed that the proportion of mature CD41+ CD42d+ BM megakaryocytes was not altered (Figure 3B), suggesting Mk maturation may not be affected by the P1-MRIPV knock-in. Following enrichment for CD41-expressing cells, we analyzed the ploidy of the CD41+ CD42d−, and CD42d+ megakaryocytes (Figure 3C-D; supplemental Figure 3B-C), which had a mean DNA content of 3N and 25N, respectively, regardless of genotype. This therefore indicated that endomitosis is not impaired in P1-MRIPV megakaryocytes. Morphologic analysis of hematoxylin and eosin, and anti-von Willebrand factor–stained BM sections (Figure 3E-F) reinforced the conclusion that adult P1-MRIPV mice are capable of producing normal, mature megakaryocytes, possessing globulated polyploid nuclei, albeit at lower numbers compared with their WT littermates.

Analysis of MGG-stained cytospins of unfractionated BM cells cultured in pro-Mk medium for 8 days also revealed the presence of morphologically normal mature megakaryocytes (supplemental Figure 3D). Following ImageStream analysis, similar levels and distribution of anti-CD41 staining were observed in cultured WT and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV megakaryocytes, with a similar range of megakaryocytes possessing different ploidies (supplemental Figure 3E). We therefore established here that the absence of RUNX1C did not impair the ability to upregulate CD41 expression or undergo endomitosis during Mk differentiation.

We next used the MegaCult colony-forming assay to determine whether P1-MRIPV/MRIPV progenitors could yield normal colonies of mature acetylcholinesterase-expressing megakaryocytes (Figure 3G-I). Culture in promegakaryocyte media resulted in decreased CFU-Mk output by both P1-MRIPV heterozygous and homozygous PreMegEs (Figure 3H), whereas a defect was observed solely for P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegEs in multilineage MethoCult media (Figure 2A). (This presumably reflects the more stringent conditions of the MegaCult assay, with 1 or more additional factor, for example, stem cell factor, in the MethoCult assay partially compensating for a defect in Mk colony-formation.) Nonetheless, WT and P1-MRIPV heterozygous and homozygous megakaryocytes, generated in MegaCult cultures, all exhibited similar density and distribution of acetylcholinesterase activity as determined by cytochemical staining (Figure 3G). We observed a considerable variation in CFU-Mk colony size, ranging from 3 to 49 megakaryocytes per colony in WT cultures (Figure 3I). In contrast, the maximum observed colony size in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV cultures was considerably lower (19 Mk per colony) and the mean colony sizes were significantly reduced across 3 experiments (WT: 9.7, 6.5, 7.8; P1-MRIPV/+: 6.7, 7.2, 8.4; P1-MRIPV/MRIPV: 5.8, 5.2, 4.6 Mk per colony). This suggested that although Mk differentiation may not be affected, proliferation and/or cell survival are impaired by the loss of RUNX1C.

Finally, to determine whether RUNX1C is required for terminal megakaryocyte maturation, we traced proplatelet formation in megakaryocytes produced by MkPs cultured on fibronectin for up to 5 days by time lapse imaging (Figure 3J-M; supplemental Figure 3F-G; supplemental Videos 1-3). We observed similar yields of CD41+ megakaryocytes in WT and P1-MRIPV cultures (supplemental Figure 3F-G). To assess proplatelet formation, however, we omitted the CD41 antibody, which impairs thrombopoiesis. A large proportion of megakaryocytes transiently produced cytoplasmic extensions, peaking at 40% of cells at 84 hours (normalized to events at 24 hours) (Figure 3J,L). The majority did not progress to a fully mature proplatelet-forming state, possibly because of a requirement for enhanced shear stress beyond what we were able to provide in this system. However, the numbers of proplatelet-forming megakaryocytes were similar to those previously observed32 and were similar in WT and P1-MRIPV cultures (Figure 3K,M). This therefore supports the hypothesis that RUNX1C is not required for megakaryocyte maturation.

Platelet function is not impaired by the absence of RUNX1C

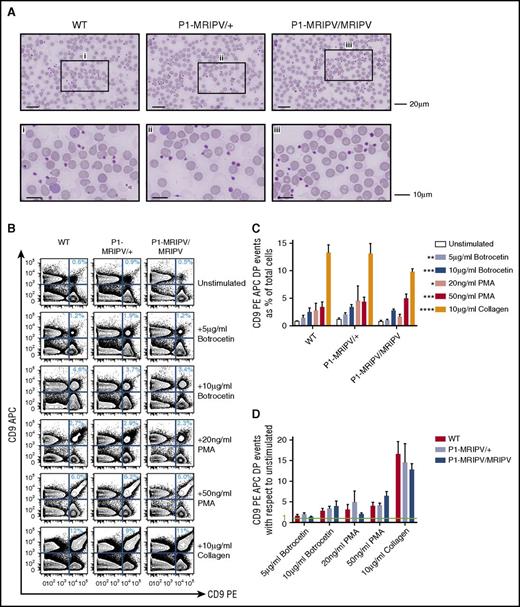

Because proplatelet-formation appears to be normal in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV mice, we investigated whether the platelets themselves were normal. The P1-MRIPV peripheral blood platelets appeared morphologically normal, with diameters ranging from 1 to 3 μm (Figure 4A), and had normal mean platelet volumes, as determined by Sysmex (supplemental Figure 4A). Moreover, although FACS analysis confirmed a drop in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV CD41+ platelet numbers, their CD41+, forward scatter area and side scatter area fluorescence intensities were not affected (supplemental Figure 4B-D).

Platelet function is not impaired by the absence of RUNX1C. (A) Morphologic analysis of peripheral blood cells, in particular platelets. May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained peripheral blood films. The bottom panel consists of enlarged images of sections indicated in the top panel. Representative images from 4 independent experiments are shown. (B-D) Assessment of platelet aggregation in vitro. (B) Representative FACS plots of CD9 APC and CD9 PE staining of unstimulated PRP and PRP treated with various agonists as indicated. (C-D) Quantitation of platelet aggregation (percent CD9 APC PE double positive events) in unstimulated and stimulated PRP (C, P values shown as compared with unstimulated) and fold increase in CD9 APC PE double positive aggregates following treatment with various agonists with respect to unstimulated PRP (D) (N = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. APC, allophycocyanin; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate.

Platelet function is not impaired by the absence of RUNX1C. (A) Morphologic analysis of peripheral blood cells, in particular platelets. May-Grünwald-Giemsa–stained peripheral blood films. The bottom panel consists of enlarged images of sections indicated in the top panel. Representative images from 4 independent experiments are shown. (B-D) Assessment of platelet aggregation in vitro. (B) Representative FACS plots of CD9 APC and CD9 PE staining of unstimulated PRP and PRP treated with various agonists as indicated. (C-D) Quantitation of platelet aggregation (percent CD9 APC PE double positive events) in unstimulated and stimulated PRP (C, P values shown as compared with unstimulated) and fold increase in CD9 APC PE double positive aggregates following treatment with various agonists with respect to unstimulated PRP (D) (N = 4). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. APC, allophycocyanin; PMA, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate.

To assess platelet function, we performed an in vitro aggregation assay,33 whereby platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was isolated from WT and P1-MRIPV whole blood, separated into CD9 phycoerythrin (PE) and CD9 APC-stained fractions, and recombined. The degree of aggregation at the start and following 2 minutes’ incubation in the absence or presence of agonist stimulation was assessed by the proportion of CD9 PE/APC double positive events in the PRP (Figure 4B-D). The proportion of aggregated platelets in P1-MRIPV unstimulated PRP did not differ significantly from WT (Figure 4C) and responded similarly to exposure to agonists of varying potency, namely 5 or 10g/mL botrocetin, 20 or 50 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, or 10 μg/mL collagen (Figure 4C-D). Moreover, the degree of aggregation, as indicated by the increased forward scatter area and side scatter area in the stimulated CD9 double positive populations, was not altered (supplemental Figure 4E-G). Therefore thrombopoiesis, as indicated by platelet morphology and function, does not appear to be impaired in P1-MRIPV mice.

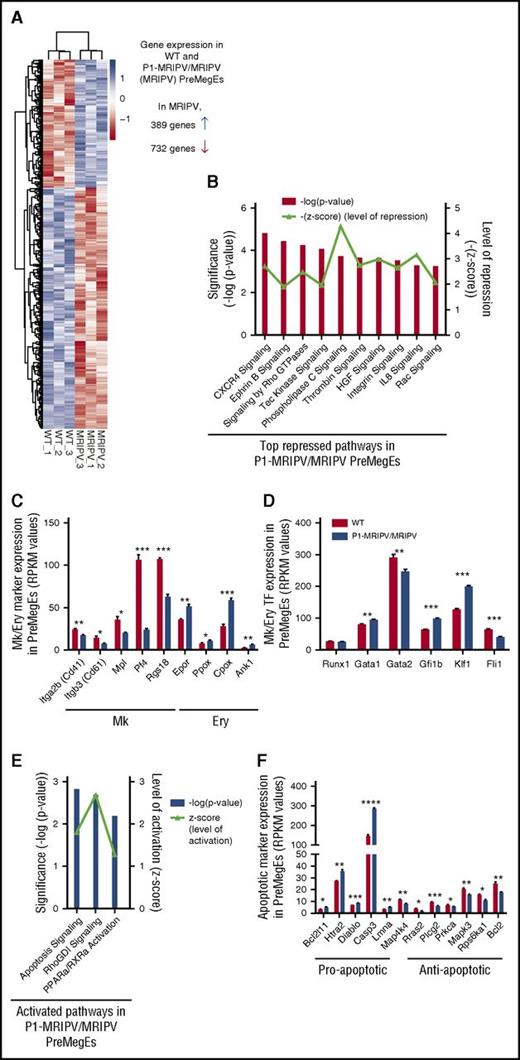

The absence of RUNX1C results in the downregulation of promegakaryocyte and the upregulation of proapoptotic transcripts in PreMegEs

Together, our data suggested a specific role for the P1-encoded RUNX1C isoform in regulating the balance of Ery and Mk output in the PreMegE fraction. To gain mechanistic insights into this and identify potential downstream regulators, we performed global gene expression analysis by RNA sequencing on WT and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV (MRIPV) PreMegEs. A total of 1121 genes were differentially expressed by twofold or greater: 732 downregulated in MRIPV cells and 389 upregulated (Figure 5A; supplemental Table 5). Following ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of the differentially expressed transcripts, we found several repressed pathways associated with megakaryopoiesis, including CXCR4, thrombin, integrin, and interleukin-8 signaling (Figure 5B). Downregulated Mk markers included Itga2b (Cd41), Itgb3 (Cd61), Mpl, Pf4, and the guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein Rgs18 (Figure 5C). RGS18 has recently been found to be directly repressed by GFI1b,34 a direct target of RUNX135 that is upregulated in MRIPV PreMegEs (Figure 5D). RGS18 expression regulates the balance of the mutually antagonistic Ery KLF1 and Mk FLI1 TFs,34 which are up- and downregulated, respectively, in MRIPV PreMegEs (Figure 5D). Analysis of RUNX1 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing data performed by the Göttgens and Grosveld groups36,37 revealed the gene loci of the majority of transcripts differentially expressed in MRIPV PreMegEs are bound by RUNX1 in megakaryocytes or murine erythroleukemia cells or both (supplemental Figure 5A-B). This includes Klf1, which has been shown to be epigenetically repressed through RUNX1’s recruitment of corepressor complexes.16 It is therefore likely that RUNX1C mediates Mk/Ery lineage decisions through the direct and indirect regulation of multiple transcriptional targets and therefore acts as a key node in this network.

The absence of RUNX1C results in the downregulation of pro-megakaryocyte and the upregulation of pro-apoptotic transcripts in PreMegEs. (A) Heat map depiction of genes at least 2-fold differentially expressed between WT and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV (MRIPV) PreMegE samples, as determined by RNA sequencing. Genes in blue are upregulated and genes in red are downregulated. (B) Signaling pathways repressed in MRIPV PreMegEs compared with WT PreMegEs as determined by IPA. (C-D) Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values of selected Mk/Ery-associated Mk/Ery markers (C) and TFs (D). (E) Signaling pathways activated in KO PreMegEs compared with WT PreMegEs as determined by IPA. (F) RPKM values of selected apoptosis-associated factors. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

The absence of RUNX1C results in the downregulation of pro-megakaryocyte and the upregulation of pro-apoptotic transcripts in PreMegEs. (A) Heat map depiction of genes at least 2-fold differentially expressed between WT and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV (MRIPV) PreMegE samples, as determined by RNA sequencing. Genes in blue are upregulated and genes in red are downregulated. (B) Signaling pathways repressed in MRIPV PreMegEs compared with WT PreMegEs as determined by IPA. (C-D) Reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) values of selected Mk/Ery-associated Mk/Ery markers (C) and TFs (D). (E) Signaling pathways activated in KO PreMegEs compared with WT PreMegEs as determined by IPA. (F) RPKM values of selected apoptosis-associated factors. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001.

Interestingly, in addition to numerous Ery-associated markers being upregulated (Figure 5C-D), the most strongly activated pathways in MRIPV PreMegEs are associated with apoptosis/cell death (Figure 5E). Among the upregulated proapoptotic factors are Caspase3, Bcl2l11, and Htra2, the loci of all 3 of which are bound by RUNX1 in megakaryocytes and murine erythroleukemia cells (Figure 5F; supplemental Figure 5A). RUNX1C may therefore be implicated in the direct regulation of apoptotic signaling and its absence may result in increased apoptosis in the Mk lineage.

RUNX1C is required for MkP proliferation and survival

Given that the absence of RUNX1C in PreMegE progenitors results in depleted Mk and enhanced Ery output, we decided to investigate whether the P1-MRIPV mutation altered the cell-cycle status of cultured BM Mk/Ery progenitors (Figure 6A-C; supplemental Figure 6A-H). Cells undergoing DNA synthesis (S-phase) were enumerated by measuring EdU incorporation in vitro (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 6A). The EdU− cells were separated into G0/1 and G2/M fractions on the basis of total DNA content. The cell-cycle status of the PreMegE, PreCFUe, and CFUe populations did not appear to be altered in the absence of RUNX1C (Figure 6B; supplemental Figure 6B-C) but the numbers of G0/1 and S-phase cells were significantly diminished in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs compared with WT (Figure 6C). Gene expression analysis of P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs suggests this may be due to reduced expression of cyclin D2 and cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4), part of the machinery which drives the G1/S transition (supplemental Figure 7A-B). The expression of other G1-associated cyclin, CDK, or CDK inhibitor genes (supplemental Figure 7A-C) was not affected, with the exception of cyclin D3, which was upregulated and may therefore partially compensate for the reduction of cyclin D2.

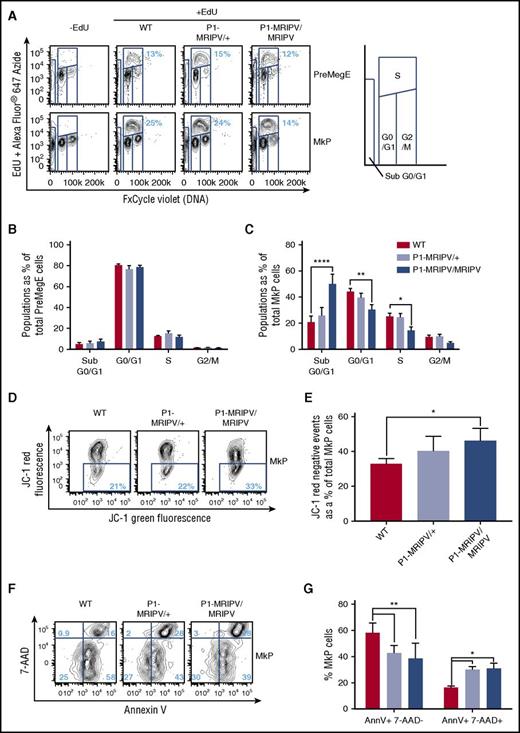

RUNX1C is required for megakaryocyte progenitor proliferation and survival. (A) Representative FACS plots of DNA content (FxCycle Violet)/EdU incorporation in PreMegE (top), and MkP (bottom) populations. (B-C) Cell-cycle analysis of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE (B) and MkP (C) populations. Sub G0/G1: FxCycle Violet negative; G0/G1: EdU− 2N; S: EdU+ 2-4N; G2/M: EdU− 4N (N = 6). (D-G) Apoptosis analysis of MkPs. (D) Representative FACS plots of JC-1 green and red fluorescence in stained MkPs. (E) Quantitation of JC-1 red negative (apoptotic) MkPs. (N = 4) (F) Representative FACS plots of 7-AAD/Annexin V (AnnV) staining of MkPs. (G) Quantitation of AnnV+ 7-AAD− (early apoptotic), AnnV+ 7-AAD+ (late apoptotic/dead) MkPs (N = 3). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. EdU, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine.

RUNX1C is required for megakaryocyte progenitor proliferation and survival. (A) Representative FACS plots of DNA content (FxCycle Violet)/EdU incorporation in PreMegE (top), and MkP (bottom) populations. (B-C) Cell-cycle analysis of WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE (B) and MkP (C) populations. Sub G0/G1: FxCycle Violet negative; G0/G1: EdU− 2N; S: EdU+ 2-4N; G2/M: EdU− 4N (N = 6). (D-G) Apoptosis analysis of MkPs. (D) Representative FACS plots of JC-1 green and red fluorescence in stained MkPs. (E) Quantitation of JC-1 red negative (apoptotic) MkPs. (N = 4) (F) Representative FACS plots of 7-AAD/Annexin V (AnnV) staining of MkPs. (G) Quantitation of AnnV+ 7-AAD− (early apoptotic), AnnV+ 7-AAD+ (late apoptotic/dead) MkPs (N = 3). *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001, ****P < .0001. EdU, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine.

Strikingly, the apoptotic “sub G0/G1” fraction was elevated 2.4-fold in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs compared with WT (50.0% vs 20.7% of total MkP cells) (Figure 6C). Together, these data suggested that the absence of RUNX1C impairs cell-cycle progression and enhances apoptosis in the megakaryocyte lineage at the MkP stage. To confirm the latter observation, apoptotic MkP numbers were assessed with measurement of mitochondrial injury through JC-1 staining (Figure 6D-E). In healthy cells, JC-1 forms red fluorescent aggregates in energized mitochondria. Therefore an increase in nonaggregated red fluorescence–negative JC-1, as observed in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs (Figure 6D-E), suggests an expansion of the apoptotic fraction. In addition, we performed Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) viability staining (Figure 6F-G). The total numbers of Annexin V+ cells were similar in WT, P1-MRIPV/+, and P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs (76.7%, 70.5%. and 66.8%. respectively), but of these a significantly greater proportion were 7-AAD+ or “late apoptotic/dead” (as opposed to 7-AAD− “early apoptotic”) in the P1-MRIPV/MRIPV populations; 15.6% of WT, 27.9% of P1-MRIPV/+, and 28.3% of P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs costained for 7-AAD and Annexin V (Figure 6G). In line with the transcriptional analysis, the absence of RUNX1C leads to increased proapoptotic gene expression in the PreMegE fraction, which results in increased apoptotic activity and subsequently decreased viability in the lineage-committed MkP subset. RUNX1C therefore appears to be crucial to prevent the progression of cell death in the megakaryocyte lineage, ultimately resulting in a competitive advantage for Ery lineage output.

Discussion

We have previously established that Runx1 P1 is the dominant promoter in adult hematopoiesis, expressed in all Runx1-expressing HSPCs, whereas P2 expression coincides with granulocyte/macrophage, lymphoid, and/or Mk commitment but appears to antagonize Ery specification.24 Although the P1-specified RUNX1C isoform is largely dispensable in hematopoietic development, P1 knock-in adult mice are subject to various hematopoietic defects, some of which are shared with the total RUNX1 conditional knockout mouse. In this study, we focused on the cause of the mild thrombocytopenia observed in both the Runx1 P1-GFP and P1-MRIPV knock-in models.24 In the total RUNX1 null adults, the thrombocytopenia is much more severe, reflecting the crucial role RUNX1-nucleated complexes play in Mk maturation, and during which RUNX1B expression might be sufficient in the absence of RUNX1C. Although the P1-MRIPV/MRIPV animals’ decreased platelet counts are unlikely to be sufficiently severe as to impair hemostasis,38 particularly because platelet function is normal, it nonetheless suggests RUNX1C’s role in megakaryopoiesis and/or thrombopoiesis may be distinct from that of RUNX1B. We subsequently observed a pro-Ery/antimegakaryocyte bias in vivo as characterized by the reduced MkP and expanded PreCFUe fractions. In vitro, P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegEs had a severely diminished Mk output, a phenotype that appeared to be at least partially the result of direct lineage priming. This was confirmed by whole transcriptome analysis, which revealed the upregulation of several red blood cell–associated transcriptional regulators and downstream effectors, such as the Erythropoietin receptor, Ankyrin 1, and components of the heme-biosynthesis pathways, in the absence of RUNX1C. By contrast, regulators of megakaryopoiesis and several Mk signaling pathways were downregulated, including CXCR4, thrombin, and integrin signaling, akin to total RUNX1 null megakaryocytes.31 This suggests replacing RUNX1C with RUNX1B partially recapitulates the defect in megakaryocyte specification associated with the depletion of total RUNX1.16 However, we did not observe the maturation defect also observed in total RUNX1 knockout models5,6,31 This implies RUNX1C has a nonredundant function to repress Ery output from PreMegEs, which cannot be completely compensated for by RUNX1B (Figure 7). An alternative interpretation is, however, that RUNX1B overexpression actively inhibits Mk commitment. A recent study suggested loss of total Runx1 causes aberrant increased commitment to the megakaryocyte lineage.30 This is in contrast to the previous finding that RUNX1 overexpression in Mk/Ery progenitors favors Mk differentiation through repression of the Ery lineage.16 Clearly, therefore, the timing and level of total RUNX1 expression is crucial for specification and differentiation of the Mk and Ery lineages.39 To this, we add the finding that the RUNX1B and RUNX1C isoforms are not equivalent when mediating lineage commitment.

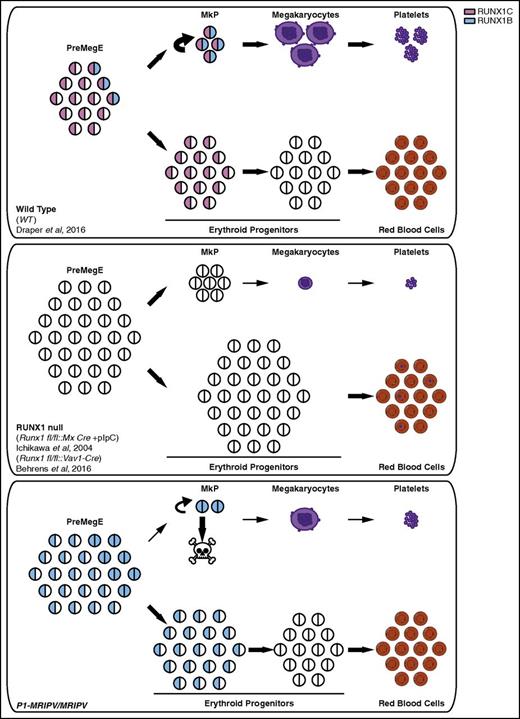

Proposed novel prosurvival role for RUNX1C in megakaryopoiesis. Models of normal erythroid and megakaryocytic specification (WT, top) and the distinct defects resulting from the complete absence of RUNX1 (RUNX1 null, center) or the specific absence of RUNX1C (P1-MRIPV/MRIPV, bottom). In WT PreMegE progenitors, megakaryocytic and erythroid lineage specification and maturation are carefully regulated to prevent, for example, thrombocytopenia or anemia. By contrast, RUNX1 null PreMegE progenitors undergo impaired maturation, resulting in the production of small, low ploidy megakaryocytes and an increased number of red blood cells containing Howell-Jolly bodies (center). P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE progenitors, however, undergo altered lineage specification but normal maturation thereafter (bottom).

Proposed novel prosurvival role for RUNX1C in megakaryopoiesis. Models of normal erythroid and megakaryocytic specification (WT, top) and the distinct defects resulting from the complete absence of RUNX1 (RUNX1 null, center) or the specific absence of RUNX1C (P1-MRIPV/MRIPV, bottom). In WT PreMegE progenitors, megakaryocytic and erythroid lineage specification and maturation are carefully regulated to prevent, for example, thrombocytopenia or anemia. By contrast, RUNX1 null PreMegE progenitors undergo impaired maturation, resulting in the production of small, low ploidy megakaryocytes and an increased number of red blood cells containing Howell-Jolly bodies (center). P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE progenitors, however, undergo altered lineage specification but normal maturation thereafter (bottom).

An interesting observation is that replacing RUNX1C with RUNX1B did not impair Mk maturation. Crucially, although Fli1 expression is decreased in the P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE population, in committed MkPs and megakaryocytes, Fli1 levels are restored to or even exceed those observed in WT cells (supplemental Figure 7D). Moreover, the Ery transcription factor Klf1 is similarly repressed in P1-MRIPV MkPs, and other Mk/Ery TFs and Mk markers have similar expression patterns in WT and P1-MRIPV MkPs (supplemental Figure 7E), suggesting surviving MkPs are transcriptionally and functionally normal (Figure 3J-M; supplemental Figure 3F-G). We previously characterized “pro-Ery” and “pro-megakaryocyte” progenitors within the immunophenotypic PreMegE fraction.24 We therefore hypothesize that RUNX1C/RUNX1B stoichiometry is crucial for balancing Mk/Ery specification at a bipotential progenitor stage, but upon Mk commitment, the absence of RUNX1C can be compensated for by the overexpression of RUNX1B in the P1-MRIPV/MRIPV model. Fli1 expression is likely to be lower in the P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegE fraction because of an increase in “pro-Ery” progenitors, and it is highly likely the remaining “promegakaryocyte” progenitors express Fli1 at levels equivalent to those seen in their WT counterparts. The restoration of Fli1 would also account for the absence of a maturation defect in the megakaryocyte lineage.40

In addition to this, polyploidization appears to proceed normally, despite the impaired cell-cycle progression in MkPs. The silencing of MYH10 by RUNX1 is crucial for the switch from mitosis to endomitosis (during which mitosis is aborted in late anaphase) to initiate polyploidization in differentiating megakaryocytes.41 At this point in megakaryopoiesis, Runx1 expression also switches from being dominated by P1-directed RUNX1C to P2-directed RUNX1B.24 Therefore the 2 isoforms may differentially regulate cell-cycle progression in progenitors or maturing megakaryocytes. We therefore speculate that the upregulation of RUNX1B in the Mk lineage24 is crucial for Mk maturation and subsequent thrombopoiesis.

The mechanisms responsible for the differences in RUNX1B and RUNX1C isoform activity remain poorly understood. The 2 proteins differ only by short N-terminal amino acid sequences and yet there is evidence that RUNX1C has stronger DNA-binding activity than RUNX1B.42 This may alter the affinity of either isoform for specific RUNX1 binding sites; for example, more weakly bound target genes may fail to recruit the RUNX1/CBFβ CBF complex in the absence of RUNX1C. Whether this may be due to the N-terminus influencing the conformation or stability of the full-length RUNX1 protein also remains to be seen. Alternatively, the N-terminus itself may act as a specific “docking site” for coregulatory protein partners. The hematopoietic activity of RUNX1 has also been found to be critically dependent on the phosphorylation of specific serine and threonine residues43 and it is possible that phosphorylation of 1 or more of these residues depends on the N-terminus. For example, interactions with kinases could be facilitated or blocked. RUNX1 is also capable of homodimerization (through the C-terminal inhibitory domain).44 In WT adult progenitors, where RUNX1C is expressed alone or in tandem with RUNX1B, RUNX1 homodimers are likely to be mostly RUNX1C-RUNX1C or RUNX1B-RUNX1C. In the P1-MRIPV/MRIPV context, the enforced presence of RUNX1B-RUNX1B homodimers may disrupt RUNX1-target gene binding or complex assembly. There are therefore several interesting avenues of investigation to pursue to gain mechanistic insights into the functions of these highly similar yet heterogeneously expressed isoforms. Such studies would benefit from the establishment of an in vitro system in which the stoichiometry of the RUNX1B and RUNX1C isoforms could be manipulated, particularly because this would offer freedom from the practical constraints imposed by the small numbers of progenitors available in vivo.

In addition to impaired Mk commitment, we detected increased apoptosis and proliferation defects in RUNX1C knockout MkPs. Whereas cell death–associated pathways are upregulated and proliferation-associated pathways repressed in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV PreMegEs, the reverse is observed in total RUNX1 knockout megakaryocytes.31 Nonetheless, a large proportion of MkPs appears to be apoptotic, even in WT BM (Figure 6D-G). It has been reported that megakaryocytes are intrinsically apoptotic and that suppression of the apoptotic mediators, Bak and Bax, is necessary for successful maturation.45 Given that the “late apoptotic” fraction is expanded in P1-MRIPV/MRIPV MkPs, it may be that the absence of RUNX1C/overexpression of RUNX1B renders the progenitors less capable of restraining the apoptotic pathways, whereas WT cells can escape this proapoptotic fate and commit to the Mk lineage with greater efficiency.

The specific role for RUNX1C in megakaryopoiesis may have important implications for in vitro platelet production. Recently, immortalized megakaryocyte progenitor cell lines (imMKCLs) were successfully derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells through transduction with BMI1, c-MYC, and BCL-XL.46 Upon attenuation of these transgenes’ expression, functional platelets, representing potential sources for transfusion into patients, could be produced in vitro. Insights into potential mechanisms for imMKCL specification were provided by the recent findings that BMI1/Ringb binds the CBF complex and that BMI1 deficiency partially phenocopies RUNX1-deficiency in terms of impaired megakaryopoiesis.47 We have determined that the RUNX1 isoforms appear to have different roles during megakaryopoiesis and the efficiency of imMKCL production may therefore be improved by sequential expression of Runx1c, promoting proliferation and survival, followed by Runx1b, to promote maturation and platelet production.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the following facilities of the Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute for technical support: Biological Resources Unit, Advanced Imaging and Flow Cytometry, the Molecular Biology Core Facility and Histology.

Research in the authors' laboratories is supported the Medical Research Council (MR/P000673/1), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/I001794/1), Bloodwise (12037), the European Union's Horizon 2020 (GA6586250) and Cancer Research UK (C5759/A20971).

Authorship

Contribution: J.E.D. designed the research, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. P.S. initiated the project, designed and performed experiments, and analyzed the data. H.S.L., M.Z.H.F., and C.M. performed bioinformatics analysis on the RNA sequencing data. V.K. and G.L. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence to: Georges Lacaud, Cancer Research UK Manchester Institute, The University of Manchester, Wilmslow Rd, Manchester M20 4BX, United Kingdom; e-mail: georges.lacaud@cruk.manchester.ac.uk; and Valerie Kouskoff, Division of Developmental Biology & Medicine, The University of Manchester, Michael Smith Building, Oxford Rd, Manchester M13 9PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: valerie.kouskoff@manchester.ac.uk.