4-1BB (CD137, tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 9) is an inducible costimulatory receptor expressed on activated T and natural killer (NK) cells. 4-1BB ligation on T cells triggers a signaling cascade that results in upregulation of antiapoptotic molecules, cytokine secretion, and enhanced effector function. In dysfunctional T cells that have a decreased cytotoxic capacity, 4-1BB ligation demonstrates a potent ability to restore effector functions. On NK cells, 4-1BB signaling can increase antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Agonistic monoclonal antibodies targeting 4-1BB have been developed to harness 4-1BB signaling for cancer immunotherapy. Preclinical results in a variety of induced and spontaneous tumor models suggest that targeting 4-1BB with agonist antibodies can lead to tumor clearance and durable antitumor immunity. Clinical trials of 2 agonist antibodies, urelumab and utomilumab, are ongoing. Despite initial signs of efficacy, clinical development of urelumab has been hampered by inflammatory liver toxicity at doses >1 mg/kg. Utomilumab has a superior safety profile, but is a less potent 4-1BB agonist relative to urelumab. Both antibodies have demonstrated promising results in patients with lymphoma and are being tested in combination therapy trials with other immunomodulatory agents. In an effort to optimally leverage 4-1BB–mediated immune activation, the next generation of 4-1BB targeting strategies attempts to decouple the observed antitumor efficacy from the on-target liver toxicity. Multiple therapeutics that attempt to restrict 4-1BB agonism to the tumor microenvironment and minimize systemic exposure have emerged. 4-1BB is a compelling target for cancer immunotherapy and future agents show great promise for achieving potent immune activation while avoiding limiting immune-related adverse events.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint blockade has revolutionized cancer treatment. Monoclonal antibodies targeting Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) and its major ligand PD-L1 have demonstrated sustained clinical benefit in diverse cancer types.1 However, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy exhibits an almost dichotomous response pattern: some patients experience rapid and durable tumor regression, but a majority of patients derive minimal or no appreciable benefit. To increase the fraction of patients that respond to immunotherapy, physicians and researchers are interrogating a dizzying array of new immunomodulatory targets and therapeutic strategies. One promising strategy involves efforts to act agonistically on immunostimulatory receptors to induce immune cell activation. Such “co-stim” strategies provide the mechanistic foundation for multiple agents in clinical development, including antibodies targeting OX40, CD27, CD40, GITR, and 4-1BB. We believe that 4-1BB, a surface glycoprotein and member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily 9, is uniquely compelling as a therapeutic target (Figure 1). In this review, we discuss the preclinical rationale for 4-1BB agonism, the recent presentations of clinical trial results from first-in-class anti-4-1BB monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), and the next generation of 4-1BB–targeted therapies.

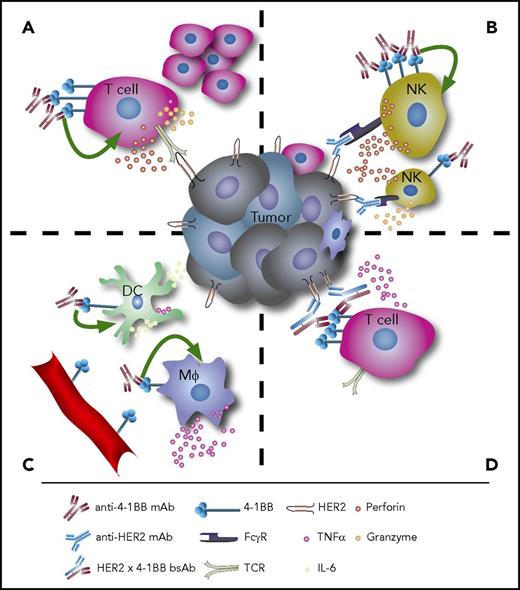

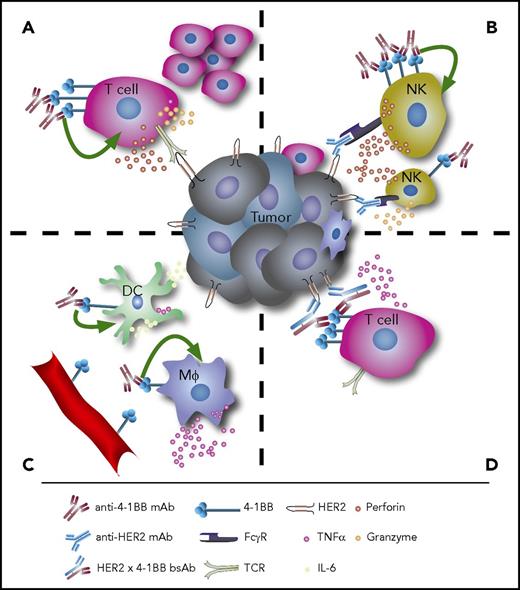

The immunomodulatory effects of anti-4-1BB therapy. (A) Agonistic anti-4-1BB mAb therapy induces T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion. (B) On NK cells, stimulation of 4-1BB enhances ADCC. (C) Agonistic anti-4-1BB mAbs can also stimulate DCs and macrophages to induce antitumor immune responses, and 4-1BB is expressed in tumor-associated vascular endothelium. (D) Bispecific antibodies targeting both 4-1BB and tumor antigens such as HER2 can lock immune effectors and target cells in close proximity and facilitate tumor cell lysis. Mφ, macrophages, TCR, T-cell receptor.

The immunomodulatory effects of anti-4-1BB therapy. (A) Agonistic anti-4-1BB mAb therapy induces T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion. (B) On NK cells, stimulation of 4-1BB enhances ADCC. (C) Agonistic anti-4-1BB mAbs can also stimulate DCs and macrophages to induce antitumor immune responses, and 4-1BB is expressed in tumor-associated vascular endothelium. (D) Bispecific antibodies targeting both 4-1BB and tumor antigens such as HER2 can lock immune effectors and target cells in close proximity and facilitate tumor cell lysis. Mφ, macrophages, TCR, T-cell receptor.

Introduction to 4-1BB signaling

4-1BB (CD137) was first identified in 1989 and initially described as an inducible gene expressed by activated cytolytic and helper T-lymphocytes.2 Functional characterization revealed that the interaction of 4-1BB and its major ligand, 4-1BBL, positively regulates T-cell immunity.3 Several antibodies targeting the 4-1BB receptor were found to provide costimulatory signaling to T cells in vitro, replicating the agonism provided by the natural 4-1BBL.4,5 In murine models of graft-versus-host disease, administration of agonistic anti-4-1BB mAbs) exacerbated cytotoxic CD8+ T cell–mediated tissue damage and accelerated the rejection of cardiac and skin allografts.6 An appreciation of the role of 4-1BB in augmenting T-cell cytotoxicity led to testing the therapeutic potential of anti-4-1BB mAbs in syngeneic cancer models. In an early demonstration of the power of immunotherapy, treatment with anti-4-1BB mAbs led to tumor clearance in the poorly immunogenic Ag104A sarcoma and highly tumorigenic P815 mastocytoma.7 Surprisingly, the same (1D8) and similar (2A, 3H3) agonistic 4-1BB-specific mAb clones were also able to ameliorate induced and spontaneous mouse models of autoimmunity.8,-10 The paradox of agonistic 4-1BB mAb mediating both T-cell activation and dysfunction is poorly understood, but may potentially be a result of the time course and dynamics of 4-1BB ligation. Initial stimulation of 4-1BB promotes the activation and proliferation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells, but these pathogenic T cells are more subsequently prone to apoptosis.

On T cells, 4-1BB is transiently expressed after T-cell receptor engagement and, when 4-1BB is engaged by the natural or artificial ligand, provides CD28-independent costimulation resulting in enhanced proliferation and Th1 cytokine production.11,12 The major biological ligand, 4-1BBL, is expressed on activated professional antigen presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages as well as B cells.3,13,-15 Ligation of 4-1BB recruits TNFR-associated factor (TRAF) 1 and TRAF2 and induces signaling through the master transcription factor NF-κB and MAPKs.16,17 TRAF1 seems to be essential for ERK 3 and NF-κB activation downstream of 4-1BB.18,19 The earliest signaling of TRAF-2 encompasses K63 E3 ubiquitin-ligase activity where TRAF2 functions as a E3 ubiquitin ligase forming K-63–linked ubiquitin polymers.20 The polymers can create docking sites for downstream mediators and signaling scaffolds such as TAK and TAB1.21 There is also structural information that the TRAF1/TRAF2 heterotrimer preferentially recruits a single cIAP molecule to initiate downstream signaling.22 Interestingly, upon ligation with agonist mAbs, 4-1BB rapidly internalizes to an endosomal compartment, from which it keeps signaling through this pathway.23,24 4-1BB signaling ultimately contributes to the secretion of interleukin 2 (IL-2) and interferon γ (IFN-γ) and upregulation of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members Bcl-xL and Bfl-1, which provide strong protection against activation-induced T-cell death.4,25,-27 In addition, accumulating data suggest substantial metabolic reprogramming occurs following 4-1BB ligation.28 Stimulation of 4-1BB with agonistic mAbs was able to raise the mitochondrial membrane potential within T cells and induce mitochondrial hypertrophy (A.T., manuscript submitted August 2017). This result mirrors the observation that chimeric antigen receptors engineered with the cytoplasmic tail of 4-1BB were able to promote oxidative phosphorylation in T cells as a result of enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis.29 Hypoxia enhances 4-1BB expression on activated T cells, and the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α is a factor for 4-1BB upregulation on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).30 TILs that express 4-1BB represent a tumor-reactive T-cell lineage; the capacity of 4-1BB expression to identify tumor antigen–experienced T cells is unique and differentiates it from other markers of T-cell activation such as CD28 and OX40.31,32 Even though 4-1BB and CD28 costimulation are said to be functionally independent, CD28 costimulation is a powerful stimulus for 4-1BB upregulation, thereby suggesting important mechanistic interactions of both costimulatory pathways.33

Although 4-1BB expression was initially thought to be restricted to activated T cells, we now understand that there is wide expression throughout the hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic compartments. 4-1BB is expressed on DC, activated monocytes, and NK cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and mast cells.34,,-37 NK cells are of particular interest given their role in tumor control and conflicting reports on the effects of agonizing 4-1BB in this population. Upon Fc-receptor triggering, NK cells upregulate 4-1BB and increase cytotoxic function in response to 4-1BB agonism, but 4-1BB agonism on resting NK cells may reduce NK cell frequency and compromise NK cell cytotoxic function.38,-40 Endothelial cells can also upregulate 4-1BB following stimulation with TNF-α, liposaccharide, and IL-1β. Expression of 4-1BB along blood vessel walls at the sites of inflammation, chiefly including tumor microvasculature and atherosclerotic areas, suggests 4-1BB may mediate leukocyte extravasation and migration.41,-43 T regulatory cells (Tregs) also express 4-1BB, but its role on this immune subset remains poorly understood; some reports suggest that treatment with anti-4-1BB mAbs can inhibit suppressive functions and others indicate ligating 4-1BB on Tregs induces Treg proliferation.44,45 Importantly, endothelial cells in hypoxic blood vessels within the tumor can upregulate 4-1BB in a hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α-mediated fashion.46 In this compartment, anti-4-1BB antibodies give rise to an increased expression of homing receptors for T-cell infiltration. As a multifunctional modulator of immune activity, 4-1BB has become a promising target to be explored in cancer immunotherapy.

Preclinical antitumor experience

Building on the initial demonstration of anti-tumor activity upon administration of agonist mAbs, the literature now includes multiple reports of tumor regressions achieved with anti-4-1BB therapy.47,48 Importantly, it is now appreciated that 4-1BB signaling can break and reverse established anergy in cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). In the classic mouse model of OVA antigen-induced T-cell anergy, treatment with anti-4-1BB mAbs restored CD8+ T-cell proliferation and cytokine secretion.49 In the absence of anti-4-1BB therapy, OVA-experienced T cells failed to expand upon subsequent challenge with OVA or a control peptide. Elegant work by Williams et al also supports the role of 4-1BB signaling in restoring the functionality of exhausted CD8+ T cells.50 In the B16.SIY model of melanoma, treatment with anti-4-1BB mAbs restored the function of CD8+ TILs that had lost the capacity to secrete IL-2. Combination treatment with anti-4-1BB and anti-LAG3 mAbs also increased the number of CD8+ TILs specific for the SIY antigen. FTY720, an inhibitor of T-cell egress from lymph nodes, was used to conclusively demonstrate that the increase in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells was a result of revitalization of previously anergic TIL and not increased T-cell trafficking to tumor. Supporting this finding, in vivo microscopy experiments revealed that anti-4-1BB mAb treatment can increase the intratumor persistence of tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells resulting in enhanced tumor cell killing.51 Despite the experimental challenges of clinical samples, translational research efforts should attempt to replicate these findings in T cells isolated from human tumors. Given our increasing understanding of the variety and potency of immunosuppressive mechanisms in the tumor microenvironment (TME), we must set a high bar for development and prioritize therapies that not only provide costimulation, but can restore cytotoxic function to dysfunctional T cells.

Efficacy of anti-4-1BB therapy has been demonstrated in multiple preclinical solid tumor models, but the available translational data strongly support investigating anti-4-1BB therapeutics in lymphoma. In 2 independent microarray datasets, only follicular lymphoma (FL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) showed an upregulation of 4-1BB.52 To confirm 4-1BB upregulation, lymph node biopsies of untreated lymphoma patients were examined; relative to healthy controls, expression of 4-1BB was significantly elevated on CD8+ T cells in FL, DLBCL, and mantle cell lymphoma. In lymphoma xenograft and syngeneic mouse models, anti-4-1BB therapy demonstrates efficacy as monotherapy.52,-54 Importantly, therapeutic activity has also been shown in Eµ-Myc transgenic mice, a model based on the Eµ-Myc translocation prevalent in Burkitt lymphoma and DLBCL.55 Compared with models based on transplanting tumor cell lines into recipient mice, transgenic tumor models may more accurately recapitulate the immune editing and eventual tumor escape that occurs in human disease. Interestingly, in the Eµ-Myc mice, anti-4-1BB mAb prolonged survival, but combination with anti-PD-1 mAb abrogated the antitumor effect and reduced the generation of CD8+ effector T cells. These results are to some extent contradictory to the efficacy observed by a combination of PD-1 blockade and anti-4-1BB mAbs against a c-myc-driven transgenic model of hepatocellular carcinoma.56 Additionally, earlier results in poorly immunogenic melanoma, ovarian cancer, and squamous lung cancer had demonstrated potent synergy between anti-4-1BB and anti-PD-1 mAbs when used in combination.57,-59 The discrepancy between the results introduces the possibility that the sequence of mAb administration may be important in some TMEs and hence immunotherapeutic regimens may need personalization based on immune contexture.

In addition to checkpoint blockade, 4-1BB-targeted therapy may synergistically combine with already approved tumor-targeted mAbs. In lymphoma patients, in which the standard of care includes rituximab (anti-CD20 mAb) therapy, an anti-4-1BB mAb therapy may increase antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and lead to enhanced tumor clearance. ADCC is the process by which target cells opsonized with antibodies are lysed by effector cells expressing activating Fcγ receptors (FcγR).60,-62 FcγRIIIa (CD16) is expressed by both NKs and macrophages and, upon recognition of the Fc portion of a mAb, induces activation.63 ADCC is believed to contribute to rituximab’s therapeutic activity; patients harboring an FcγRIIIA polymorphism with higher affinity for immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) have better clinical responses to rituximab treatment.64,,-67 The opportunity to combine anti-4-1BB and rituximab therapy exists because 4-1BB is upregulated on NK cells following binding of FcγRIIIa on NK cells to the Fc portion of rituximab.68 The addition of an agonistic anti-4-1BB mAb following CD16-mediated mAb recognition exploits this upregulation and leads to increased IFN-γ production and proliferation of NK cells.69 Anti-4-1BB therapy may increase the cytotoxic action of NK cells through ADCC; in a syngeneic and a xenotransplanted lymphoma model, sequential administration of anti-CD20 mAb followed by anti-4-1BB mAb had potent antilymphoma activity.53 NK-mediated ADCC and synergy between tumor-targeted antibodies and 4-1BB agonistic mAbs has also been demonstrated with cetuximab (anti-EGFR mAb), trastuzumab (anti-HER2 mAb), and elotuzumab (anti-SLAMF7 mAb).70,71 Activating NK cells and increasing ADCC is synergistic to the established stimulatory effects of 4-1BB on T cells. The dual mechanism of action and robust preclinical data supporting agonistic 4-1BB-targeted mAbs justifies clinical development in a variety of treatment settings.

Urelumab

Urelumab (BMS-663513), a fully human IgG4 mAb, was the first anti-4-1BB therapeutic to enter clinical trials. Urelumab does not block the interaction of 4-1BB with its ligand. Initial clinical results were presented in 2008.72 Despite encouraging hints of efficacy, the phase 1 and 2 data eventually revealed a liver toxicity that appeared to be on target and dose dependent, halting clinical development. Development restarted in 2012 and rapidly expanded to include trials that tested urelumab in combination with rituximab, cetuximab, elotuzumab, and nivolumab (NCT01471210, NCT01775631, NCT02110082, NCT02252263, NCT02253992). Recently, data were presented on urelumab as monotherapy and in combination with nivolumab.73 Once again, a liver toxicity signal emerged at the 0.3 mg/kg dose level, resulting in dosing of urelumab in expansion cohorts at a flat dose of 8 mg per patient; the pharmacokinetic profile of the 8-mg flat dose was comparable to 0.1 mg/kg dosing. The reduced dose improved the liver toxicity, and, importantly, the urelumab and nivolumab combination demonstrated tolerability, only 16% of patients treated in the combination cohort expansion experienced a grade 3-4 treatment-related adverse event (TRAE).

The efficacy results with low-dose urelumab monotherapy and the combination with nivolumab were largely disappointing. In the monotherapy cohorts, none of the solid tumor patients had an objective response, including 17 patients in a colorectal cancer expansion cohort, 15 patients in a head and neck cancer (SCCHN) cohort, and 31 patients with other solid tumors. In the combination of urelumab at 8 mg every 4 weeks with nivolumab at 240 mg every 2 weeks, objective responses were limited. Only 1 of 22 SCCHN patients, 0 of 14 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients who had progressed on an anti-PD-1/PD-L1, and 1 of 20 NSCLC patients who were naive to treatment with an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agent responded. Both the NSCLC patient and the SCCHN patient who responded to therapy were treatment naive and had shown high PD-L1 staining on their tumor biopsies. In 46 metastatic melanoma patients who were naive to treatment with an anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agent, 1 patient (2%) had a complete response, 17 patients (37%) had a partial response, and another 5 patients (11%) had unconfirmed partial responses. These responses could be attributed to the activity of nivolumab, but the responses in PD-L1-negative cases suggest urelumab may be contributing to the observed efficacy. In the combination, 0 of 19 patients with DLBCL responded. However, in the monotherapy urelumab trial, 3 of 60 patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma achieved a complete response and an additional 3 patients had a confirmed partial response. Complete remissions were observed in patients with FL, marginal zone lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma. Partial remissions were observed in patients with FL (n = 1) and DLBCL (n = 2). We eagerly await the results of the urelumab and rituximab combination trial, in which preliminary results suggest activity in rituximab refractory patients.74

Despite the limited clinical activity of urelumab at the tolerated dose, we remain enthusiastic about the development of agonist anti-4-1BB mAbs. As mentioned, the recent data with urelumab in metastatic melanoma patients demonstrated similar response rates between patients with PD-L1 positive and PD-L1 negative tumors, suggesting urelumab may be expanding the pool of patients who respond to anti-PD-1 mAbs. Importantly, data from clinical trials of urelumab demonstrate an immune-stimulatory pharmacodynamic effect. In elegant work conducted by Srivastava et al, the immunomodulatory effects of urelumab were examined in a phase 1b, open-label, neoadjuvant trial of cetuximab in SCCHN.75 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from patients and analyzed before and 24 hours after cetuximab treatment, and after 2 cycles of cetuximab plus urelumab treatment. The results demonstrate that 4-1BB expression on NK cells was enhanced 24 hours after cetuximab treatment and that the combination of cetuximab and urelumab increases DC maturation and antiapoptotic and cytotoxic signaling in NK cells. The observed effects on DCs recapitulate earlier work illustrating the importance of DCs in mediating 4-1BB-mediated antitumor immunity. Using Batf3−/− transgenic mice and the B16-OVA mouse model, Batf3-dependent DC function was shown to be essential to the efficacy elicited by anti-4-1BB mAb therapy.76 These experiments reveal a critical role for DC-mediated crosspriming of tumor antigens.

Experiments with urelumab in humanized mouse models confirm the potency and immunomodulatory capacity of urelumab. In mice engrafted with patient-derived gastric carcinoma followed by PBMC from the same patient, treatment with the combination of urelumab and nivolumab slowed tumor growth and increased the number of activated human T cells producing IFN-γ.77 The disconnect between compelling preclinical and biomarker results and the current clinical experience with urelumab may be explained by inadequate dosing regimens. The 8-mg flat dose required to avoid liver toxicity is likely too low for sufficient target occupancy and therapeutic activity. However, urelumab in our hands is a potent agonist mAb that deserves to be studied in strategies that can avoid the liver toxicity and achieve proper levels of drug exposure in the TME.

Utomilumab

Utomilumab (PF-05082566) is a humanized IgG2 monoclonal antibody that activates 4-1BB while blocking binding to endogenous 4-1BBL. Initial clinical data with utomilumab were reported in 2014 and suggested utomilumab may have a superior safety profile relative to urelumab because no significant elevations in liver enzymes or dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) occurred in 27 treated patients.78 In 2015, data from the phase 1 combination of utomilumab and rituximab in patients with CD20+ non-Hodgkin lymphoma were presented.79 This study evaluated a wide range of utomilumab doses (0.03-10 mg/kg) and the standard dose of rituximab (375 mg/m2) in 38 patients. Again, utomilumab demonstrated a favorable safety profile: only 3 patients had grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs) and no DLT occurred. The maximum tolerated dose was estimated as >10 mg/kg. Analysis of PBMC demonstrated an increase in circulating memory CD8+ T cells, especially at a 10 mg/kg dose. Importantly, a subset of rituximab-refractory, indolent lymphoma patients appeared to derive clear benefit: 2 complete responses in FL patients were durable, lasting beyond 2 years; 3 partial responses in this population were also observed. Preliminary data from the expansion cohort of rituximab-refractory FL were recently reported.80 Of 24 FL patients who were refractory to rituximab, 33% (8/24) experienced tumor shrinkage, with 4 patients achieving a complete response. Of the 48 treated patients, 27% had grade ≥3 treatment-emergent AEs, but no patients discontinued because of toxicity. These results are encouraging and enrollment in the FL expansion cohort is ongoing (NCT01307267).

In 2016, data on the phase 1b trial exploring the combination of utomilumab and pembrolizumab were presented.81 Pembrolizumab was administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks and dose escalation of utomilumab tested doses ranging from 0.45 to 5.0 mg/kg. In total, 23 patients were treated with the combination; the median number of prior therapies in the cohort was 3. The majority of patients had NSCLC (n = 6), renal cell carcinoma (n = 5), or SCCHN (n = 3); other solid tumor patients were included, and only 1 treated patient had melanoma. Utomilumab had no evidence of additive toxicity in the combination with pembrolizumab and no grade 3 or 4 TRAE or DLT occurred. The combination demonstrated clinical benefit with 2 complete responses and 4 partial responses confirmed and 1 unconfirmed partial response. These responses appeared to be durable, with 5 of the patients sustaining tumor shrinkage for >10 months. Biomarker analysis of peripheral circulating lymphocytes revealed a trend for patients with tumor responses to have elevated levels of activated and effector memory CD8+ T cells at cycle 5 day 1 following treatment. These data are encouraging and justify continued exploration of the combination because without a larger number of treated patients, but it is impossible to distinguish between the benefit of utomilumab and the effects of pembrolizumab monotherapy. The excellent safety profile of utomilumab has unlocked the possibility of combination immunotherapy trials. Currently, utomilumab is in trials in combination with avelumab (anti-PD-L1 mAb) in DLBCL (NCT02951156) and in 1 of the first triple-agent combination immunotherapy regimens with avelumab and an anti-OX40 mAb (NCT02554812). In our hands, utomilumab is a weaker agonist than urelumab. Comparatively, utomilumab drives less 4-1BB signaling and less induction of NF-kB. although many basic biochemical and mechanistic questions remain to dissect this discrepancy between utomilumab and urelumab, the known differences between mAbs include: intrinsic agonistic activity, immunoglobulin subclass, Fc receptor binding profile, targeted epitope on 4-1BB, and 4-1BBL blockade capacity. Future clinical trials will help elucidate the contribution of these properties to the activity of anti-4-1BB mAbs and determine what level of agonism is optimal for therapeutic efficacy.

Safety

A recent, comprehensive safety analysis of patients treated with urelumab confirmed a strong association between transaminitis and urelumab dose.82 In light of reported liver function test abnormalities and hepatic TRAEs, there has been extensive research conducted to understand the mechanistic underpinnings of 4-1BB-related liver toxicity. In BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice, treatment with anti-4-1BB mAbs induced mononuclear inflammation, composed primarily of infiltrating T cells in the portal area of the liver.83,84 The toxicity was T-cell and 4-1BB dependent and did not occur in Rag−/− or 4-1BB−/− mice. The liver-infiltrating T cells were not oligoclonal, and it was suggested that the related autoimmune reaction was not driven by self-antigens, but instead by nonspecific CD8+ T-cell activation. CD8+ T-cell depletion abrogated liver pathology, as did neutralizing the effects of TNF or IFN-γ. Later work confirmed that 4-1BB is expressed on approximately 10% of CD8+ CD44high T cells in the liver and bone marrow of unimmunized mice, which may explain the response of T cells in the liver to anti-4-1BB therapy.85 Additional research in hepatitis B virus-transgenic mice suggested the liver toxicity was induced by non-specific memory CD8+ T cells in a MHC-I independent fashion.86 Ongoing research focuses on investigating the contribution of the myeloid compartment, IL-27, and Foxp3+ regulatory T cells on 4-1BB mAb-mediated hepatotoxicity.87 Further mechanistic studies regarding the different mode of 4-1BB-mediated antitumor immunity vs liver toxicity might pave the way for the development of novel 4-1BB agonists with favorable side effects.88 The primary challenge is to identify the key cellular events that contribute to liver inflammation and develop strategies for uncoupling toxicity and antitumor efficacy.

Given the differences in ligand-blocking effects of preclinical and clinical anti-4-1BB mAbs, it is worth considering the effects of disrupting 4-1BBL binding on toxicity. In pilot studies, Shuford et al tested an array of anti-mouse 4-1BB antibodies and found no association between 4-1BB ligand blocking and T-cell stimulation in vitro.89 Interestingly, anti-4-1BB mAbs such as 3H3 and 2A, which are widely used in preclinical studies of cancer, have opposing effects on 4-1BB ligand binding, but demonstrate similar liver toxicity profiles. Therefore, it seems likely that 4-1BB ligand engagement does not determine 4-1BB-mediated toxicity or anti-tumor efficacy, especially in the mouse system. Ongoing investigations hope to determine the importance of human 4-1BBL on anti-human 4-1BB liver toxicity and the role of other potential 4-1BB ligands in driving signaling. Both extracellular matrix and Galectin-9 have been proposed to be 4-1BB binding partners; however, the former interaction is not conserved in the human system.90,91 It is of particular importance to discover and further understand the contribution of other ligand-receptor interactions on 4-1BB signaling.

Given the expense, time, and cost to patients associated with clinical trials, using preclinical systems that can more accurately model and predict immune-related AEs will accelerate the identification of limiting toxicities and optimal therapeutic combinations. An important contribution in this effort is the development of transgenic mice in which genes for human immunomodulatory receptors and their ligands have been introduced in the loci of the murine counterpart (knock-in [KI] mice). These models allow researchers to study therapeutic effects in the context of a functional immune system and therefore may facilitate more accurate assessment of immune-related toxicity.92 The development of human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) gene KI mice illustrates the power of this strategy. In CTLA-4 KI mice, treatment with anti-hCTLA-4 mAbs induces the same pattern of autoimmune toxicities observed in patients treated with the anti-CTLA-4 mAb ipilimumab.93 KI mice with human Fc receptors also provide a system for beginning to dissect the mechanisms of therapeutic antibodies with different human IgG isotypes.94 Although both IgG4 and IgG2 induce similar but limited ADCC, it is still unclear if the difference in the isotypes between urelumab and utomilumab contributes to the observed efficacy or safety profile. In addition to generating more robust preclinical models, the prediction of immune-related AEs will require the development of better insights into the foundational genetic, epigenetic, and environmental elements that govern immunity in humans. KI mice with human 4-1BB exist and are being used to test efficacy and safety of anti-4-1BB targeted agents (CrownBio and Biocytogen).

Next-generation strategies

Multiple efforts are ongoing to develop therapeutic strategies that maximize 4-1BB agonism while minimizing systemic exposure and 4-1BB-induced toxicity. Restricting 4-1BB agonists to the TME is known to be effective in mouse models: tumor cells transfected with 4-1BBL or with membrane-attached anti-4-1BB single-chain variable fragments elicit durable, antitumor responses.95,-97 Three strategies for enriching 4-1BB agonist activity in the TME have recently progressed to clinical development: intratumoral (IT) administration of mAbs, bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) that engage 4-1BB and a tumor antigen or tumor stromal component, and “masked” antibodies that become “unmasked” by tumor-specific protease activity.

4-1BB agonists offer an ideal candidate for IT mAb therapy.98 The dose-limiting hepatotoxicity observed with urelumab may be mitigated by IT administration because of the disproportionate concentration of mAb in the TME; lower systemic exposure should limit the on-target, inflammatory side effects. Additionally, IT administration maximizes 4-1BB agonist exposure to lymphocytes already in the TME, the accepted target population for anti-4-1BB therapy. Antibody diffusion outside the tumor is likely to activate lymphocytes resident in the downstream, draining lymphatic tissue which may confer additional therapeutic benefit. Finally, tumor penetration of systemically delivered mAbs remains poorly defined and IT administration ensures TME exposure.

Multiple 4-1BB-targeted bispecific antibodies are in preclinical or early clinical development and have demonstrated promising early data. The bsAbs are designed to promote target-mediated clustering of 4-1BB; in the absence of the tumor target, minimal clustering will occur and immune activation will be limited. The amount of clustering, or hypercrosslinking, dictates the magnitude of the activating signal induced by 4-1BB. The initial reports of 4-1BB–bispecific molecules leveraged aptamer technology and were composed of an agonistic 4-1BB oligonucleotide aptamer conjugated to an aptamer that binds PSMA or vascular endothelial growth factor.99,100 Recently, bsAb formats were presented that combine 4-1BB-targeting with a variable region for the tumor targets HER2 or fibroblast activation protein.101,-103 In the TME, the bsAb functions as a bridge between cells expressing HER2 or fibroblast activation protein and activated immune cells that express 4-1BB. By locking immune effectors and target cells in close proximity, the bsAb theoretically enhances 4-1BB clustering and signal induction. Both urelumab and utomilumab achieve 4-1BB clustering through the Fc receptors on neighboring leukocytes; bsAbs aim to replace the Fc-mediated clustering with clustering driven by target expression on or near tumor cells. The advantages of this strategy are twofold: systemic toxicities should be limited because activation will be confined to tissue expressing the target antigen and tumor-mediated 4-1BB clustering should drive potent agonism.

Insights into tumor-specific protease dysfunction and novel techniques for protein engineering have created an exciting opportunity to develop immunotherapeutic mAbs that are selective for tumor tissue. A hallmark of cancer is increased pericellular proteolytic activity in the TME and surrounding tissue. An increase in proteolytic activity within the TME provides the opportunity to develop proteolytically activated antibodies. One such strategy involves expressing antibodies with peptide “masks” that occlude the paratope. The masking sequence is connected to the mAb by a substrate linker that can be cleaved by tumor-associated proteases like matriptase, urokinase plasminogen activator, or the cysteine protease legumain. Ideally, the peptide mask attenuates mAb binding to the target in healthy tissue, but in the TME, tumor-specific protease activity cleaves the linker substrate and exposes the paratope of the parental antibody. Ongoing efforts have demonstrated preclinical proof of concept for this strategy using anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 mAbs.104 Recently, a masked version of ipilimumab demonstrated reduced peripheral T-cell activation relative to standard ipilimumab.105 After a single dose of 10 mg/kg in cynomolgus macaques, the masked ipilimumab did not increase Ki-67+ CD4+ or CD8+ T cells to levels observed with the same dose of standard ipilimumab. A similar masking approach with a 4-1BB mAb may represent an attractive strategy for enriching mAb exposure in the TME and avoiding hepatotoxicity.

Conclusion

The existing experimental and clinical data clearly support the therapeutic potential of targeting the 4-1BB pathway for cancer immunotherapy. 4-1BB plays an important role in T-cell activation, persistence, and memory and increases NK-mediated ADCC. Despite 4-1BB-induced hepatotoxicity with urelumab, ongoing efforts will elucidate clinical and therapeutic strategies for unlocking the antitumor effects of targeting 4-1BB. As anti-4-1BB therapies advance in clinical development, it will be important to continue to interrogate the many mechanistic questions that remain unanswered. Future lines of inquiry include: the role of 4-1BB in the biology of Treg cells and APCs, the functional crosstalk between 4-1BB and other immunomodulatory surface receptors, and the long-term, T-cell reprogramming effects and toxicity mechanisms of 4-1BB agonists. As our understanding of 4-1BB biology increases, so will our capacity to develop efficacious therapies, avoid toxicities, and develop prognostic and therapeutic biomarkers.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Isabella Lazzareschi for her helpful comments on the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: C.C., M.F.S., J.W., and I.M. wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: I.M. served in an advisory role for BMS, Roche-Genetech, Lilly, Bayer, F-Star, Alligator, Pieris, and Merck-Serono; and received grants from BMS, Roche-Genentech, and Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cariad Chester, Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection, Stanford University School of Medicine, 299 Campus Dr, Stanford, CA 94305; e-mail: cariad.chester@gmail.com.