TO THE EDITOR:

Cuplike nuclei (CLN) (nuclei with prominent invagination) are recognized as a distinctive morphologic finding in the blasts of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).1-6 They are seen in ∼20% of all AML cases2,4,5 and are associated with normal karyotype, absence of CD34 and HLA-DR, and mutation of fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) and/or nucleophosmin 1 (NPM1) genes.1-6 CLN have not been reported on B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), with the exception of rare single case reports.7-9 The incidence of CLN and their possible association with certain B-ALL subtypes or cytogenetic abnormalities are unknown.

To answer these questions, we retrospectively reviewed 425 B-ALL cases diagnosed at Children's Mercy Hosptal from January of 1996 to January of 2017. Patients had an age range of 10 days to 19 years (median, 3.92 years) and a male-to-female ratio of 1.12:1. The cases were retrieved from the database of all leukemia cases diagnosed at Children's Mercy Hospital and selected based on the availability of diagnostic bone marrow (BM) and/or peripheral blood (PB) smears for review. A total of 49 cases had diagnostic PB smears only; the remainder had BM smears only or both BM and PB smears. Blinded 500-cell blast counts were performed by 2 pathologists (W.L. and A.I.R.). Nuclear invagination spanning ≥25% of the nuclear diameter was defined as CLN. The percentages of CLN identified by 2 pathologists for each case were averaged. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Children’s Mercy Hospital.

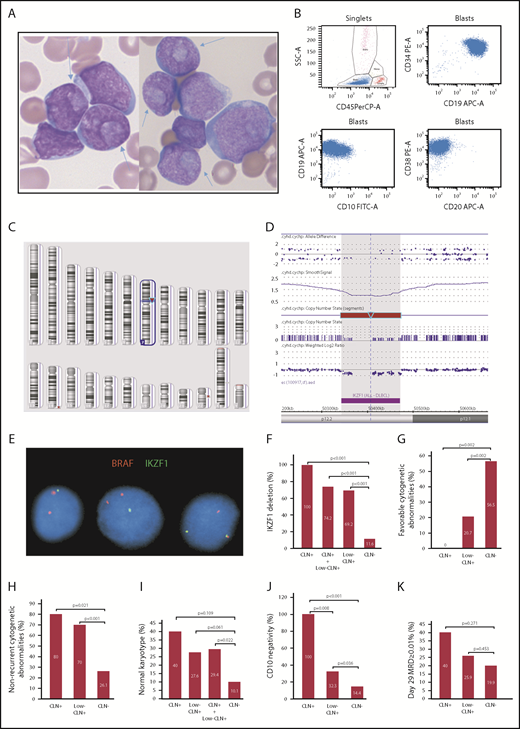

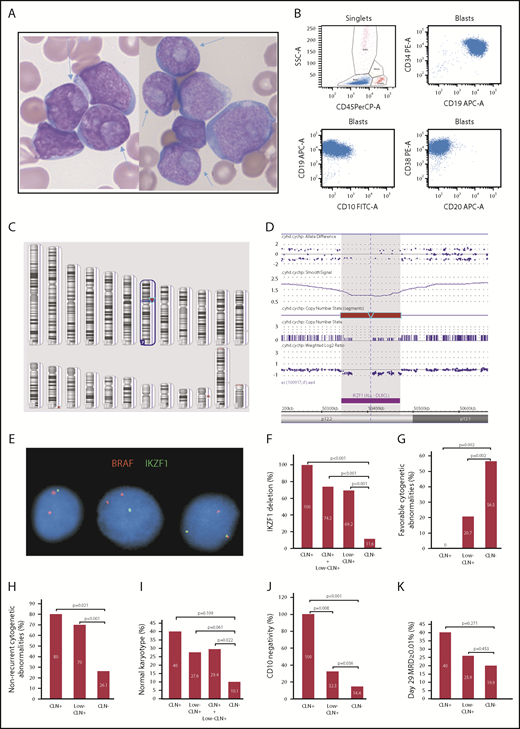

We identified 5 (1.2%) CLN+ B-ALL cases (Table 1, cases 1-5) based on the criterion for CLN+ AML (≥10% CLN). Because this criterion is arbitrarily defined, we also looked for B-ALL cases with lower numbers of CLN and identified 31 (7.3%) low-CLN+ cases (Table 1, cases 6-36) with ≥2% to 10% CLN. Together, there were 8.5% B-ALL cases with ≥2% CLN. Cases with <2% CLN were considered CLN negative (CLN−). CLN were present in variably sized and shaped lymphoblasts (Figure 1A). The percentages of CLN in the PB and BM of the same patient were not significantly different.

Morphologic, immunophenotypic and cytogenetic features of precursor B-ALL with CLN. (A) CLN (arrows) in variably sized blasts in BM smears from cases 1 and 2 (Wright-Giemsa stain, original magnification ×1000). (B) Representative immunophenotype of CLN+ B-ALL cases: CD34+CD19+CD20−CD10− or CD10 dimly and partially positive. Dot plots of 4-color FCM analysis performed using a BD FACSCanto and analyzed with BD FACSDiva software. (C) Image of Affymetrix CytoScan HD whole-genome microarray showing 7p12.2 deletion as the sole clonal aberration (red arrow). (D) Zoomed in image of the 7p12.2 deletion showing loss of the entire IKZF1 gene. (E) FISH image showing a single green signal for IKZF1 in the first 2 cells (from left to right), which indicates 1 copy loss of IKZF1. The 2 red BRAF (7q34) signals serve as an internal chromosome 7 control. Comparison of CLN+, low-CLN+, and CLN− frequencies with IKZF1 deletion (F), favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (ETV6/RUNX1 or high hyperdiploidy) (G), nonrecurrent cytogenetic abnormalities (H), normal karyotype (I), CD10 negativity or partial negativity (J), and day-29 BM MRD ≥ 0.01% (K).

Morphologic, immunophenotypic and cytogenetic features of precursor B-ALL with CLN. (A) CLN (arrows) in variably sized blasts in BM smears from cases 1 and 2 (Wright-Giemsa stain, original magnification ×1000). (B) Representative immunophenotype of CLN+ B-ALL cases: CD34+CD19+CD20−CD10− or CD10 dimly and partially positive. Dot plots of 4-color FCM analysis performed using a BD FACSCanto and analyzed with BD FACSDiva software. (C) Image of Affymetrix CytoScan HD whole-genome microarray showing 7p12.2 deletion as the sole clonal aberration (red arrow). (D) Zoomed in image of the 7p12.2 deletion showing loss of the entire IKZF1 gene. (E) FISH image showing a single green signal for IKZF1 in the first 2 cells (from left to right), which indicates 1 copy loss of IKZF1. The 2 red BRAF (7q34) signals serve as an internal chromosome 7 control. Comparison of CLN+, low-CLN+, and CLN− frequencies with IKZF1 deletion (F), favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (ETV6/RUNX1 or high hyperdiploidy) (G), nonrecurrent cytogenetic abnormalities (H), normal karyotype (I), CD10 negativity or partial negativity (J), and day-29 BM MRD ≥ 0.01% (K).

Then we looked at the available data from conventional chromosome and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies, chromosomal microarray analysis, and flow cytometry (FCM) studies for these cases. Conventional chromosome analysis and FISH studies for B-ALL panel (BCR/ABL1, ETV6/RUNX1, KMT2A, RUNX1, D4Z1, D10Z1, D17Z1) were performed for the majority of the patients as standard patient care. FISH with probes for IKZF1 deletion and/or CRLF2 rearrangement was performed on B-ALL cases diagnosed after January of 2014 (n = 85). Chromosome microarray as standard patient care was also performed on recent B-ALL cases (n = 56). These tests were performed following the manufacturer’s and/or Children’s Mercy Hospital’s corresponding protocols. Minimal residual disease (MRD) at day 29 of induction was evaluated by multiparameter FCM. We noticed that all 5 CLN+ or low-CLN+cases with available IKZF1 test results showed IKZF1 deletion. This finding led us to suspect that there might be an association between CLN and IKZF1 deletion.

To test this hypothesis, we performed IKZF1 FISH on B-Plus–fixed paraffin-embedded BM clot sections from 26 CLN+/low-CLN+ cases diagnosed before 2014. The same FISH analysis was also performed on 5 randomly selected CLN− cases diagnosed before 2014 for control purposes. These 5 CLN− cases and all 64 CLN− cases diagnosed after January of 2014 were combined as the control group for a comparison and correlation study. The association of CLN with IKZF1 deletion, B-ALL with no recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities, normal karyotype, favorable cytogenetic abnormalities, immunophenotype, MRD, male-to-female ratio, and National Cancer Institute risk group was examined using Fisher’s exact test. Patient ages among different groups were compared using the Student t test. White blood cell counts among different groups were compared using the Student t test and the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was defined by P < .05. All P values were 2 sided.

We found that all CLN+ cases and 32% of low-CLN+ cases showed an early B-precursor phenotype (CD34+CD20−CD10− or partially negative; Figure 1B). The incidence of this phenotype in these 2 groups was significantly higher than in the control group (14.4%; P < .001 and .05, respectively; Figure 1J). Strikingly, all CLN+ cases and 69.2% low-CLN+ cases showed monoallelic IKZF1 deletions that were detected by FISH and/or microarray (Figure 1C-E). These frequencies were significantly higher than in the control group (11.6%; P < .001; Figure 1F). Recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities listed in the current World Health Organization book10 were present in only 1 CLN+ case (KMT2A rearranged) and 9 low-CLN+ cases (4 ETV6/RUNX1, 2 hyperdiploid, 1 BCR/ABL1, 1 KMT2A rearranged, 1 iAMP21). The incidence of B-ALL with no recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities in CLN+ (80%) and low-CLN+ (70%) cases was significantly higher than in the control group (26.1%; P < .05 and .001, respectively; Figure 1H). The incidence of normal karyotype in CLN+ (40%) and low-CLN+ (27.6%) cases was higher than in the control group (10.1%), but the difference was only statistically significant when the 2 CLN+ groups were combined (Figure 1I). The incidence of favorable cytogenetic abnormalities (ETV6/RUNX1, hyperdiploidy > 50 chromosomes) in CLN+ (0%) and low-CLN+ (20.7%) cases was significantly lower than in the control group (56.5%; P < .05 and .01, respectively; Figure 1G). There were no significant differences in age, gender, white blood cell count, or National Cancer Institute risk group. Ten cases (5 CLN+, 5 low-CLN+) were tested for FLT3 internal tandem duplication and NPM1 mutations, using polymerase chain reaction–based methods, in B-Plus–fixed paraffin-embedded BM clot samples. Only half of the results were interpretable, and all were negative, which indicate that CLN in B-ALL are probably not associated with FLT3 or NPM1 mutations.

B-ALL is 1 of the most common pediatric cancers. It is cytogenetically, molecularly, and phenotypically heterogeneous. Although current risk-stratified treatment results in a cure rate of ∼ 90% for pediatric B-ALL,11,12 relapse and chemotherapy-related morbidity and mortality remain significant challenges for oncologists. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia remains the leading cause of cancer-related death in children and young adults. Failure to categorize the leukemia into the proper risk group with appropriate intensity of chemotherapy likely contributes to early relapse and worse clinical outcome.

The IKZF1 gene encodes a transcription factor, Ikaros, which is a critical regulator for lymphoid differentiation.13,14 IKZF1 deletions have been found in 70% to 80% of BCR-ABL1+ B-ALL,15,16 40% of BCR-ABL1–like B-ALL,16 35% of Down syndrome–associated B-ALL,17 and 10% to 15% of BCR-ABL1− pediatric B-ALL.15,18-20 Common deletions include entire gene deletions or focal deletions involving exons 4 to 7. All studies have demonstrated IKZF1 deletions as unfavorable cytogenetic changes associated with poor outcome. Most studies16,18,20-22 have identified them as an independent prognostic predictor, although this has been questioned by a few other studies.19,23 As reported recently,24 intensifying the treatment of B-ALL with IKZF1 deletions was shown to reduce the relapse rate and improve overall survival, indicating that IKZF1 deletions can be used as an independent risk-stratifying marker.

It is unlikely that CLN are an independent prognostic marker for B-ALL. Although day-29 BM with MRD ≥ 0.01%, which is a strong predictor for worse prognosis, was present more often in CLN+ (2/5, 40%) and low-CLN+ (7/27, 25.9%) cases than in the control group (35/176, 19.9%), the differences were not statistically significant (P > .05; Figure 1K). Kaplan-Meier analysis (data not shown) found no significant survival difference between CLN+ and CLN− groups. All CLN+ cases that were tested for IKZF1 deletion and showed ≥0.01% MRD were positive for IKZF1 loss. Because IKZF1 deletion is a predictor for poor outcome, the possible worse prognosis of a CLN+ B-ALL case may reflect the higher chance of having IKZF1 deletions.

In conclusion, our data confirm that CLN are uncommon in B-ALL and reveal a novel association between CLN and IKZF1 deletion in pediatric B-ALL. CLN+ cases are more likely to have an early B-precursor phenotype, normal karyotype, or nonrecurrent cytogenetic abnormalities and are less likely to have favorable cytogenetic abnormalities. Although FISH and/or microarray testing may not be readily available, cytomorphologic assessment is available almost everywhere. CLN can be easily recognized by pathologists with this knowledge and limited training.4 Thus, recognizing CLN is clinically useful, especially when cytogenetic results are not available. It can help to predict the presence of a very important prognostic marker, IKZF1 deletion, at a high positive-predictive value (100% with ≥10% CLN or 74.2% with ≥2% CLN).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Brian Lee, Division of Health Services and Outcomes Research, Children’s Mercy Hospital, for help with statistical analysis and are grateful for the technical support from the cytogenetic laboratory, histology laboratory, and flow cytometry laboratory at Children’s Mercy Hospital.

This work was supported by Children’s Mercy Cancer Center Auxiliary Research Fund.

Authorship

Contribution: W.L., L.D.C., and K.J.A. designed the study; W.L. and A.I.R. reviewed BM and/or PB smears and assessed blast morphology; W.L. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; L.D.C. analyzed the data, created Table 1, and revised the manuscript; and K.J.A., A.I.R., L.S., A.A.A., M.S.F., and D.L.Z. analyzed parts of the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and gave valuable comments or suggestions.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Weijie Li, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Children’s Mercy Hospital, 2401 Gillham Rd, Kansas City, MO 64108; e-mail: wli@cmh.edu.