Key Points

Chemotherapy-induced mutagenesis may cause drug resistance mutations in ALL, leading to relapse.

Thiopurines in particular likely cause drug resistance mutations in NT5C2, NR3C1, and TP53.

Abstract

To study the mechanisms of relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), we performed whole-genome sequencing of 103 diagnosis-relapse-germline trios and ultra-deep sequencing of 208 serial samples in 16 patients. Relapse-specific somatic alterations were enriched in 12 genes (NR3C1, NR3C2, TP53, NT5C2, FPGS, CREBBP, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, WHSC1, PRPS1, and PRPS2) involved in drug response. Their prevalence was 17% in very early relapse (<9 months from diagnosis), 65% in early relapse (9-36 months), and 32% in late relapse (>36 months) groups. Convergent evolution, in which multiple subclones harbor mutations in the same drug resistance gene, was observed in 6 relapses and confirmed by single-cell sequencing in 1 case. Mathematical modeling and mutational signature analysis indicated that early relapse resistance acquisition was frequently a 2-step process in which a persistent clone survived initial therapy and later acquired bona fide resistance mutations during therapy. In contrast, very early relapses arose from preexisting resistant clone(s). Two novel relapse-specific mutational signatures, one of which was caused by thiopurine treatment based on in vitro drug exposure experiments, were identified in early and late relapses but were absent from 2540 pan-cancer diagnosis samples and 129 non-ALL relapses. The novel signatures were detected in 27% of relapsed ALLs and were responsible for 46% of acquired resistance mutations in NT5C2, PRPS1, NR3C1, and TP53. These results suggest that chemotherapy-induced drug resistance mutations facilitate a subset of pediatric ALL relapses.

Introduction

Although cure rates of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) approach 90% in developed countries,1 relapse rates remain high in developing countries where most ALL cases occur.2 Relapsed ALL has a poor prognosis mainly due to therapy resistance.3 Elucidating the genetic basis of acquired chemoresistance will help identify therapeutic strategies to prevent or eradicate relapsed disease.

Previous studies of relapsed pediatric ALL identified relapse-specific mutations in NR3C1, TP53, NT5C2, PRPS1, CREBBP, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and WHSC1, causing resistance to various drug classes.4-9 Interestingly, relapse-associated mutations in certain genes, including NT5C2 and PRPS1, were generally not detectable at diagnosis even with high-depth sequencing,5,6,9,10 suggesting that these drug resistance mutations were acquired after diagnosis and possibly during treatment, in contrast to other cancer settings in which resistance mutations preexist subclonally.11-14 In addition, high-depth sequencing of serial bone marrow samples taken before remission showed exponential increases of PRPS1-containing clones foreshadowing overt relapse.5

To gain more insight into the genetic basis and the mutational processes of relapsed ALL, we performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of diagnosis, relapse, and germline samples from 103 Chinese pediatric patients with ALL, most of whom were enrolled on the Shanghai Children’s Medical Center ALL-2005 frontline treatment protocol. WGS was used to identify copy alterations, structural variants, and mutational signatures associated with relapse, since previous studies by us and others relied primarily on exome or targeted sequencing,4-9 which has limited ability in these areas. We also performed ultra-deep (median, 3669×; range, 2291-30 535×) sequencing of 208 serial bone marrow samples of 16 patients (7-23 samples per patient) collected during ALL therapy. The resulting data were used to construct the trajectory of temporal evolution, providing unprecedented insight into the comparative dynamics of ALL subclones under the selective pressure of chemotherapy.

Methods

Patient samples

Parent(s) or guardian(s) of patients provided informed consent for research with tissue. Patients were treated at Shanghai Children’s Medical Center, the Second Hospital of Anhui Medical University, or the Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital in Tianjin. Each hospital’s institutional review board approved all analyses.

WGS and somatic variant analysis

WGS was performed at WuXi NextCode by using Illumina HiSeq X-Ten instruments and aligned to GRCh37-lite with BWA.15 Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels were detected with Bambino,16 copy number variation with CONSERTING,17 and structural variation by CREST.18 Details regarding capture validation sequencing can be found in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Functional analysis of NR3C1, FPGS, TP53, and NT5C2 mutations

NR3C1, TP53, and NT5C2 mutant or wild-type complementary DNAs were stably expressed through lentiviral transduction in REH and/or Nalm6 cells. Drug–response assays were performed by using the MTT or CellTiter-Glo Luminescent assays. FPGS enzymatic activity was measured by using purified mutant or wild-type FPGS proteins as reported,19 followed by a methotrexate (MTX) polyglutamation enzymatic assay. Additional details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Tumor growth rate estimation and modeling of time to relapse

Estimation of tumor growth rate was based on the best fit (curve_fit from scipy in Python) of a logistic function to minimal residual disease (MRD) measurements of 19 patients with B-cell ALL (B-ALL) over time as relapse progressed. Given the estimated tumor growth rate, we estimated, based on the model of Diaz et al12 and Durrett and Moseley,20 the upper limit of expected relapse time. Additional details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

SNV mutational signature analysis

SigProfiler21 was used to extract mutational signatures from somatic SNV data, resulting in 2 novel signatures dissimilar from known COSMIC version 2 signatures (cosine similarity <0.9). To determine whether thiopurines were the cause of novel signature B, MCF10A cells were treated for 7 weeks with 10 nM of 6-thioguanine, followed by WGS of single-cell clones, using a procedure similar to that performed by others.22 Additional details are provided in the supplemental Methods.

Results

Landscape of genomic alterations in relapsed ALL

To characterize the genomic profiles of relapsed leukemias, we performed WGS at median 30× coverage (supplemental Figure 1A) on matched diagnosis, relapse, and germline samples of 103 patients with relapsed pediatric ALL (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Table 1A), including 87 patients with B-ALL and 16 with T-cell ALL (T-ALL); this formed a representative cohort of all relapsed ALL patients treated at Shanghai Children’s Medical Center (supplemental Table 1B; supplemental Methods). Somatic alterations acquired at diagnosis or relapse were identified, including SNVs, indels, copy number variations, and structural variations (SVs). Coding variants, including 4606 SNVs, 253 indels, and 1463 SVs, were also validated by capture sequencing at ∼500×; their variant allele fractions (VAFs) were highly concordant between WGS and capture sequencing (supplemental Figure 1B; supplemental Tables 2-4). Importantly, next-generation sequencing–based tumor purity (supplemental Figure 1C) exhibited high concordance with leukemia blast proportions measured by using flow cytometry for ALL samples (r = 0.81; P < 1 × 10−21). Relapsed ALLs generally retained most coding (mean, 79%; range, 14%-100%) and noncoding (mean, 75%; range, 4%-98%) mutations and all subtype-defining genetic lesions present at diagnosis, consistent with their shared genetic lineage.

Relapse-enriched somatic variants in pediatric ALL. (A) ALL subtypes of the patient cohort. The number of cases in each subtype and in B- or T-lineage is labeled in the outer and the inner circles, respectively. Subtypes of singleton cases are binned to B/Other (IGH-MYC and hypodiploid) or T/Other (HOXA). D, diagnosis; R, relapse. (B) Schematic showing sequencing performed and number of patients (n) sequenced with each platform. (C) Pathways mutated among shared variants (diagnosis and relapse [D+R]) compared with relapse-specific variants (R); pathways are defined in supplemental Table 5. Color indicates mutation type identified in a single patient; box indicates pathways enriched at relapse. Slice width represents the proportion of patients with mutation of at least 1 gene in indicated pathway. (D) Heatmap of significantly mutated genes and known driver genes across the cohort, with genes in rows and patients in columns. The 12 genes at top are those enriched specifically among relapse-specific variants (supplemental Methods), and genes in the bottom portion are frequently present at both diagnosis and relapse. At right, a bar plot of the percentage of patients mutated for each gene is shown, along with the pathway to which the gene belongs. Gray indicates that the mutation is shared at diagnosis and relapse (D+R), red indicates relapse-specific (R), and blue indicates diagnosis-specific (D). Subtypes and B- vs T-lineage are indicated at top. CDKN2A mutations occurred in 49% of samples, which is above the axis limit.

Relapse-enriched somatic variants in pediatric ALL. (A) ALL subtypes of the patient cohort. The number of cases in each subtype and in B- or T-lineage is labeled in the outer and the inner circles, respectively. Subtypes of singleton cases are binned to B/Other (IGH-MYC and hypodiploid) or T/Other (HOXA). D, diagnosis; R, relapse. (B) Schematic showing sequencing performed and number of patients (n) sequenced with each platform. (C) Pathways mutated among shared variants (diagnosis and relapse [D+R]) compared with relapse-specific variants (R); pathways are defined in supplemental Table 5. Color indicates mutation type identified in a single patient; box indicates pathways enriched at relapse. Slice width represents the proportion of patients with mutation of at least 1 gene in indicated pathway. (D) Heatmap of significantly mutated genes and known driver genes across the cohort, with genes in rows and patients in columns. The 12 genes at top are those enriched specifically among relapse-specific variants (supplemental Methods), and genes in the bottom portion are frequently present at both diagnosis and relapse. At right, a bar plot of the percentage of patients mutated for each gene is shown, along with the pathway to which the gene belongs. Gray indicates that the mutation is shared at diagnosis and relapse (D+R), red indicates relapse-specific (R), and blue indicates diagnosis-specific (D). Subtypes and B- vs T-lineage are indicated at top. CDKN2A mutations occurred in 49% of samples, which is above the axis limit.

Samples were classified into 15 subtypes (Figure 1A; supplemental Methods) by gene fusion and karyotype analysis; somatic alterations in 22 significantly mutated and other known driver genes are shown in Figure 1D and supplemental Figure 2 (see also https://pecan.stjude.cloud/proteinpaint/study/scmc-relapse; supplemental Table 5; supplemental Methods). Pathway analysis showed enrichment at relapse of mutations in the glucocorticoid receptor, p53, purine and folate metabolism, and mismatch repair pathways (Figure 1C). Specifically, 12 genes were enriched for relapse-specific alterations, including 11 known relapse-related genes: corticosteroid receptors NR3C1 and NR3C2 and epigenetic regulators CREBBP and WHSC1, which affect glucocorticoid response4,9,23 ; nucleotide metabolism enzymes NT5C2, PRPS1, and PRPS2 and DNA mismatch repair genes MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2, which affect thiopurine response5-7,24 ; and the tumor suppressor gene TP53 (Figure 1D). We also discovered a novel relapse-enriched gene, FPGS, a folate metabolism gene linked to MTX resistance in leukemia cell lines25 but which has, to our knowledge, not been hitherto described in patient samples. Fifty-eight of 103 relapsed ALLs harbored at least 1 somatic alteration in these 12 genes, and 22 of the 57 patients harbored mutations in ≥2 of the 12 genes. Seven of the 12 genes had relapse-specific alterations in both B-ALL and T-ALL, whereas PRPS1, MSH2, FPGS, CREBBP, and WHSC1 alterations were exclusively in B-ALL (although not significant; P > .3). Notably, acquisition of TP53 mutations at relapse, which occurred in 9 cases, was accompanied by acquired mutations in mismatch repair, glucocorticoid receptor, or purine or folate metabolism pathways.

Seven of the relapse-specific NR3C1 variants were assessed functionally, and they were found to lack glucocorticoid transcriptional activation activity and to confer resistance to prednisolone (Figure 2A) but not daunorubicin (supplemental Figure 3), indicating specificity for glucocorticoid resistance. FPGS causes polyglutamation of folates and antifolates such as MTX, with consequent intracellular retention and thus increased activity of MTX.26 We studied 7 purified relapse-specific FPGS mutant proteins, all of which had decreased enzymatic MTX polyglutamation (15%-65% of wild-type) (Figure 2B), suggesting that ALL cells with these mutations have low MTX polyglutamates and thus MTX resistance.27 Indeed, loss of FPGS activity is associated with MTX resistance in ALL.28-30 Four FPGS mutations clustered in the C-terminal glutamate ligase domain; two (G417R and P421L) were near the putative glutamate-binding site31 and may disrupt glutamate binding (supplemental Figure 4A). Two other glutamate ligase domain mutations (R369C and G370V) resided near the adenosine triphosphate–binding site and the linker connecting N- and C-terminal lobes, suggesting disruption of adenosine triphosphate–dependent polyglutamation. Four mutations (E115K, K167T, D195H, and R558 > PGES) occurred outside the active site and may not affect catalysis directly. We also observed relapse-specific focal (<5 Mb) FPGS deletions in 4 patients and a promoter deletion in 1 patient (supplemental Figure 4B, E). Three patients had multiple FPGS alterations, including copy plus SNV alterations. Finally, FPGS messenger RNA expression was also significantly reduced at relapse across the cohort (supplemental Figure 4C-D). Thus, multiple genetic and transcriptional mechanisms may contribute to decreased FPGS activity at relapse.

Functional characterization of relapse-specific mutations. (A) Top, relapse-specific NR3C1 mutation locations within the NR3C1 protein, with the x-axis indicating amino acid position. Bottom, their effects on NR3C1 transcriptional activator activity (left) and ALL sensitivity to glucocorticoids (right). Left, mutant, wild-type (WT), and empty vector (EV) transcription activator activity was measured in HEK293T cells by using the reporter gene assay. Mutations are grouped and color-coded according to their locations in protein domains. Right, glucocorticoid sensitivity (ie, dose–response curve) was measured by using cell viability after treatment with prednisolone for 72 hours in ALL cell line REH expressing WT or mutant NR3C1 (color-coded according to protein domain), using the MTT assay. The y-axis represents percent cell viability compared with untreated control. Error bars indicate standard error. (B) Top, FPGS relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, their effects on polyglutamation enzymatic activity using MTX as the substrate. Purified mutant and WT FPGS were tested at 3 different amounts (5 ng, 2.5 ng, or 1.25 ng) in triplicate, and the enzymatic activity was relative to the activity of the WT at 5 ng. The first 2 columns represent controls with no MTX or FPGS. Error bars represent standard error. (C) Top, NT5C2 relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, cell viability of REH or Nalm6 cells treated with 6-thioguanine (6-TG, left) or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP, right) in cells expressing indicated NT5C2 mutations (or WT NT5C2 or uninfected control [-]). Error bars represent standard deviation. (D) Top, TP53 relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, functional validation of TP53 R248Q and R196G. Nalm6 cells underwent TP53 knockout (KO) by CRISPR and were reintroduced with TP53 WT, R196G, or the known hotspot R248Q mutant. Left, cell viability in response to idarubicin and vincristine treatment. Right, fold change in proportion of Annexin V–positive apoptotic cells (top) and in proportion of EdU+ cells in S phase (bottom; values <1.0 indicate G1/S checkpoint arrest induced by functional p53 in response to treatment), compared with untreated controls, after treatment with 1 µM (top) or 0.01 µM (bottom) idarubicin for 24 hours. Error bars represent standard deviation. Dotted line in right panels represents 1.0. Protein domains are as reported on pecan.stjude.cloud (A,D), National Center for Biotechnology Information (B), or Dieck et al32 (C).

Functional characterization of relapse-specific mutations. (A) Top, relapse-specific NR3C1 mutation locations within the NR3C1 protein, with the x-axis indicating amino acid position. Bottom, their effects on NR3C1 transcriptional activator activity (left) and ALL sensitivity to glucocorticoids (right). Left, mutant, wild-type (WT), and empty vector (EV) transcription activator activity was measured in HEK293T cells by using the reporter gene assay. Mutations are grouped and color-coded according to their locations in protein domains. Right, glucocorticoid sensitivity (ie, dose–response curve) was measured by using cell viability after treatment with prednisolone for 72 hours in ALL cell line REH expressing WT or mutant NR3C1 (color-coded according to protein domain), using the MTT assay. The y-axis represents percent cell viability compared with untreated control. Error bars indicate standard error. (B) Top, FPGS relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, their effects on polyglutamation enzymatic activity using MTX as the substrate. Purified mutant and WT FPGS were tested at 3 different amounts (5 ng, 2.5 ng, or 1.25 ng) in triplicate, and the enzymatic activity was relative to the activity of the WT at 5 ng. The first 2 columns represent controls with no MTX or FPGS. Error bars represent standard error. (C) Top, NT5C2 relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, cell viability of REH or Nalm6 cells treated with 6-thioguanine (6-TG, left) or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP, right) in cells expressing indicated NT5C2 mutations (or WT NT5C2 or uninfected control [-]). Error bars represent standard deviation. (D) Top, TP53 relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, functional validation of TP53 R248Q and R196G. Nalm6 cells underwent TP53 knockout (KO) by CRISPR and were reintroduced with TP53 WT, R196G, or the known hotspot R248Q mutant. Left, cell viability in response to idarubicin and vincristine treatment. Right, fold change in proportion of Annexin V–positive apoptotic cells (top) and in proportion of EdU+ cells in S phase (bottom; values <1.0 indicate G1/S checkpoint arrest induced by functional p53 in response to treatment), compared with untreated controls, after treatment with 1 µM (top) or 0.01 µM (bottom) idarubicin for 24 hours. Error bars represent standard deviation. Dotted line in right panels represents 1.0. Protein domains are as reported on pecan.stjude.cloud (A,D), National Center for Biotechnology Information (B), or Dieck et al32 (C).

Most of the 17 NT5C2 mutations we observed were reported previously,32 whereas H352D and R363L (Figure 2C) have not been. NT5C2 H352D and R363L caused resistance to 6-thioguanine and, to a lesser extent, to 6-mercaptopurine, as did the R367Q positive control variant.10,32 We also observed 10 relapse-specific sequence alterations in TP53 (Figure 2D), most frequently at R248Q.33 Replacement of endogenous wild-type TP53 with R248Q or the less common R196G mutation conferred resistance to idarubicin and vincristine, key drug classes used during induction therapy,34 and abrogated p53-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest.

Modeling of resistant clone appearance times

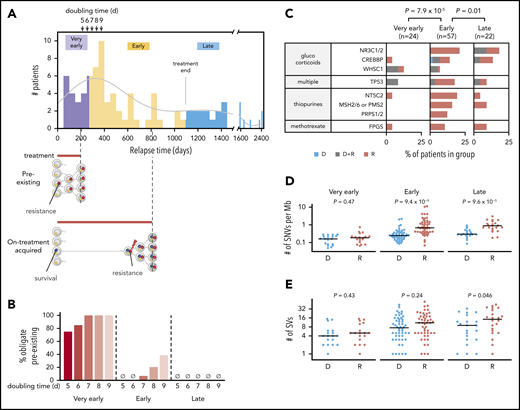

Relapse times may indicate whether resistant subclones preexist at diagnosis or appear later12 (supplemental Figure 5A). Relapses occurred between 2 months and 6.6 years after diagnosis in our cohort. Based on the timeline of ALL treatment, these relapses were categorized into 3 groups: very early relapse (<9 months from diagnosis, before maintenance therapy; 23% of cohort), early relapse (9-36 months, during maintenance; 55%), and late relapse (>36 months, after completion of therapy; 21%). To project the expected relapse time based on the assumption of a single preexisting resistant cell at diagnosis, we first estimated the growth rate of drug-resistant clones12,20,35 using published deep sequencing–derived allele fractions of PRPS1-mutant clones in serial samples of 4 patients with B-ALL collected during progression to relapse5 ; this process yielded an aggregated doubling time of 7.4 days (supplemental Figure 5B). We also analyzed 70 sequential MRD measurements from 19 patients with B-ALL from our cohort during progression toward relapse (supplemental Figure 5C), yielding an aggregated 5.3-day doubling time for resistant clones in B-ALL. These doubling times are comparable to a reported median potential doubling time of 7.4 days for B-ALL based on cell cycle analysis, in which 75% of samples ranged from 5 to 9 days36 (supplemental Figure 5D). We therefore tested doubling times of 5 to 9 days to estimate how many relapses were likely due to preexisting resistant subclones. This modeling applies to B-ALL, representing 84% of our cohort, as insufficient longitudinal MRD data in T-ALL were available to determine the T-ALL doubling time in our cohort.

Assuming the presence of a single resistant cell at diagnosis (day 0) and a 5-day doubling time, we would expect >95% of patients to have relapsed by day 213 given a relapse tumor burden of ∼250 billion37 leukemia cells; for a 9-day doubling time, 95% would have relapsed by day 374 (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 5E; supplemental Methods). This preexisting resistance model fits well with the relapse times of the very early group (“pre-existing”), with 75% to 100% of very early relapses considered preexisting based on doubling times of 5 to 9 days (Figure 3B). Early relapses, by contrast, may have occurred through a 2-step process in which a “persister”38 clone survives treatment yet cannot proliferate until acquiring a bona fide resistance mutation during treatment (“on-treatment acquired”), which is also supported by the mutational signature analysis presented later. Alternatively, early relapses may have occurred through delayed proliferation (>9-day doubling time), perhaps during specific treatment regimens. Late relapses may arise from a persister clone that survives until the treatment protocol ends, without acquiring a bona fide resistance mutation. Such cases may simply resume proliferation upon treatment cessation, leading to relapse.

Evidence of preexisting and later-appearing resistant clones. Panels A and B include B-ALL samples; panels C through E include both B- and T-ALL samples. (A) Histogram (top) indicates the distribution of relapse times across B-ALL samples in the cohort (50-day bins) together with kernel density estimation (gray line). Arrows indicate predicted relapse time of 95% of the B-ALL cohort given a single preexisting resistant cell and a doubling time of 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 days. Purple indicates very early relapses (<9 months from diagnosis), likely relapsing due to a preexisting resistant clone (schematic at bottom). Yellow represents early relapses (9-36 months), which appear at times consistent with postdiagnosis appearance of the resistant clone from a persister clone that survives initial treatment (bottom), or delayed growth (≥9-day doubling time) of a preexisting clone. Blue represents late relapses (>36 months) appearing after the time treatment had ended on all protocols (3 years, “treatment end” bar). These clones may have survived treatment without outright resistance and relapse at times consistent with resumption of proliferation at treatment cessation. “Survival” (blue circles) and “resistance” (red circles) represent mutations conferring these phenotypes. (B) Percentage of very early, early, or late B-ALL relapses consistent only with the preexisting resistant subclone scheme. The percentages are calculated based on projected relapse times when the doubling time of the resistant clone is 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 days (shown in arrows in panel A at top); if a sample relapsed before that projected time, it was considered preexisting. (C) Distribution of relapse-enriched variants in the 3 patient groups with very early (<9 months), early (9-36 months), and late (>36 months) relapse. D indicates diagnosis-specific variants, R indicates relapse-specific, and D+R indicates shared. Also shown are the mutation burden (panel D) and number of SVs (panel E) at diagnosis (D) and relapse (R) in the 3 groups along with P values from the 2-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test for D vs R. Variants at D or R in panels D and E included shared variants.

Evidence of preexisting and later-appearing resistant clones. Panels A and B include B-ALL samples; panels C through E include both B- and T-ALL samples. (A) Histogram (top) indicates the distribution of relapse times across B-ALL samples in the cohort (50-day bins) together with kernel density estimation (gray line). Arrows indicate predicted relapse time of 95% of the B-ALL cohort given a single preexisting resistant cell and a doubling time of 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 days. Purple indicates very early relapses (<9 months from diagnosis), likely relapsing due to a preexisting resistant clone (schematic at bottom). Yellow represents early relapses (9-36 months), which appear at times consistent with postdiagnosis appearance of the resistant clone from a persister clone that survives initial treatment (bottom), or delayed growth (≥9-day doubling time) of a preexisting clone. Blue represents late relapses (>36 months) appearing after the time treatment had ended on all protocols (3 years, “treatment end” bar). These clones may have survived treatment without outright resistance and relapse at times consistent with resumption of proliferation at treatment cessation. “Survival” (blue circles) and “resistance” (red circles) represent mutations conferring these phenotypes. (B) Percentage of very early, early, or late B-ALL relapses consistent only with the preexisting resistant subclone scheme. The percentages are calculated based on projected relapse times when the doubling time of the resistant clone is 5, 6, 7, 8, or 9 days (shown in arrows in panel A at top); if a sample relapsed before that projected time, it was considered preexisting. (C) Distribution of relapse-enriched variants in the 3 patient groups with very early (<9 months), early (9-36 months), and late (>36 months) relapse. D indicates diagnosis-specific variants, R indicates relapse-specific, and D+R indicates shared. Also shown are the mutation burden (panel D) and number of SVs (panel E) at diagnosis (D) and relapse (R) in the 3 groups along with P values from the 2-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test for D vs R. Variants at D or R in panels D and E included shared variants.

To further test whether early relapses are due to on-treatment acquired resistance rather than to a preexisting resistant clone, we compared the prevalence of relapse-specific mutations in the 12 resistance genes (Figure 1D) in the very early, early, and late groups. Indeed, early relapses had a statistically higher number of cases with relapse-specific mutations (65% of patients) in the 12 genes compared with very early (17%; P = 7.9 × 10−5) or late (32%; P = .01) relapses (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the SNV mutational burden increased in early (median, 2.8-fold increase; P = 9.4 × 10−9) and late (3.0-fold; P = 9.6 × 10−5) relapses but not in very early relapses (Figure 3D), consistent with the preexisting resistance model for very early relapses. Notably, the paucity of relapse-specific mutations in the very early group remained significant even after adjusting for the time interval for mutation acquisition (supplemental Figure 6). Interestingly, structural variant mutational burdens increased significantly only in late relapses (Figure 3E).

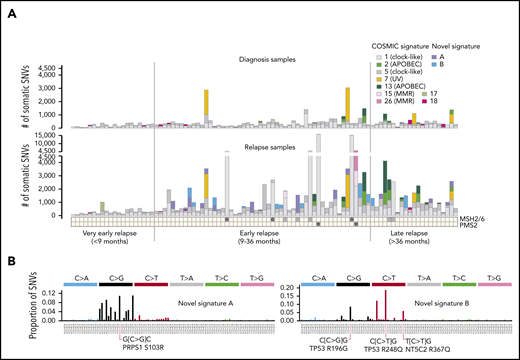

Mutational signature analysis reveals chemotherapy-associated mutagenesis

To examine the mutational processes contributing to the increased mutation burden at relapse (Figure 3D), genome-wide mutational signatures were analyzed based on trinucleotide context39 (supplemental Figure 7). Eleven mutational signatures were identified (supplemental Methods), including 9 known signatures present at both diagnosis and relapse and 2 novel relapse-specific signatures (Figure 4A). The predominant mutational signatures at diagnosis and relapse were COSMIC signatures 1 and 5, which are clock-like signatures associated with 5-methylcytosine deamination and uncertain etiology, respectively.40 All 5 hypermutators at relapse (mutation burden >5000 SNVs) had a dramatic increase in signatures 1, 15, and/or 26 (the latter two being mismatch repair-associated); 4 had acquired bi-allelic loss of mismatch repair genes MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2. APOBEC signatures 2 and 13 were present in 10 ETV6-RUNX1 ALLs and one hyperdiploid ALL, 4 of which acquired >1000 APOBEC-associated SNVs at relapse. Notably, 10 of 11 APOBEC-positive ALLs had an increased proportion of APOBEC-induced mutations among relapse-specific variants (mean proportion, 0.48) compared with shared (present at diagnosis and relapse) variants (mean proportion, 0.29; P = .01 by paired Student t test) (supplemental Figure 8A-B), indicating enrichment of APOBEC in later evolution as in lung41 and breast42 cancers. Consistent with our previous findings,43 the UV-associated signature (UV, signature 7) was present in 4 patients at diagnosis but had significantly decreased contribution to relapse-specific mutations (mean proportion, 0.15) compared with shared mutations (mean proportion, 0.65) in all 4 (paired Student t test, P = .002). Thus, UV-induced mutagenesis is likely an early event.

Evolution of mutational signatures from diagnosis to relapse. (A) Contribution of known COSMIC signatures and 2 novel relapse-specific signatures to somatic SNVs identified in the matched diagnostic (top) or relapse (bottom) samples of patients in the 3 relapse time categories. Samples are sorted according to increasing relapse time from left to right. Relapse-specific mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes (ie, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2) are indicated at bottom; samples with bi-allelic mutations are marked by a star. MMR indicates mismatch repair deficiency-associated signatures. (B) Trinucleotide mutation spectra of novel signatures A and B, with the contexts of selected example relapse-specific gene variants indicated.

Evolution of mutational signatures from diagnosis to relapse. (A) Contribution of known COSMIC signatures and 2 novel relapse-specific signatures to somatic SNVs identified in the matched diagnostic (top) or relapse (bottom) samples of patients in the 3 relapse time categories. Samples are sorted according to increasing relapse time from left to right. Relapse-specific mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes (ie, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2) are indicated at bottom; samples with bi-allelic mutations are marked by a star. MMR indicates mismatch repair deficiency-associated signatures. (B) Trinucleotide mutation spectra of novel signatures A and B, with the contexts of selected example relapse-specific gene variants indicated.

The 2 novel relapse-specific signatures were found only in early and late relapses but not in very early relapses (Figure 4A-B; supplemental Figure 7; supplemental Table 6), suggesting that they may be chemotherapy induced. Novel signature A, detected in 14 relapses (causing a median of 421 SNVs; range, 73-1304) was characterized by most C>G trinucleotide contexts except those flanked 3′ by G. Novel signature B, detected in 13 relapses (median, 352 SNVs; range, 79-1062) was characterized by mutations of C at CpG dinucleotides, with C>T most common, followed by C>G and C>A. The 5′ flanking base was, in order of frequency: C, A, T, or rarely G. Two relapsed ALLs harbored both signatures. Interestingly, novel signature A was enriched in hyperdiploid cases (57% hyperdiploid in signature-positive cases; 14% in signature-negative cases; Fisher’s exact test, P = .001), whereas novel signature B was not subtype-specific. Each novel signature was found in both B- and T-lineage ALL samples, with no significant lineage specificity.

Novel signature B–associated mutations exhibited transcription-induced strand bias, suggesting mutational processes repaired by transcription-coupled repair,22,39 whereas novel signature A had minimal strand bias (supplemental Figure 9). Because strand bias was toward C>T or C>G on the transcribed strand, novel signature B–induced mutagenesis likely originates with guanine, not cytosine, in C-G base pairs.

Most novel signature A– or signature B–positive relapses harbored the novel signature within the dominant relapse-specific clone (13 of 14 patients, or 10 of 13 patients, respectively), as the signatures were present in higher VAF relapse–specific mutations, rather than exclusively in subclonal lower VAF mutations (supplemental Figure 10). This finding suggests that chemotherapy-induced mutagenesis is an early event giving rise to the dominant relapse clone, and together with our modeling, suggests on-treatment acquisition of resistance in a subset of relapses (Figure 3A).

We also analyzed SV signatures by classifying SV breakpoints as blunt breakpoints, breakpoints with flanking microhomology, or breakpoints with nontemplated sequence (NTS) inserted. As reported previously,44 the ETV6-RUNX1 subtype was enriched for NTS SVs (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < .0005) and slightly decreased in NTS SVs at relapse compared with diagnosis (supplemental Figure 8C-D). Interestingly, the mutation burden of novel signature B correlated with relapse-specific SVs with NTS inserted (r = 0.749) and with more CG>NN dinucleotides (r = 0.767) (supplemental Figure 11), suggesting a therapy causing multiple mutation types. The CG>NN dinucleotide pattern matches the SNV profile of novel signature B, which mutates at CpGs (Figure 4B).

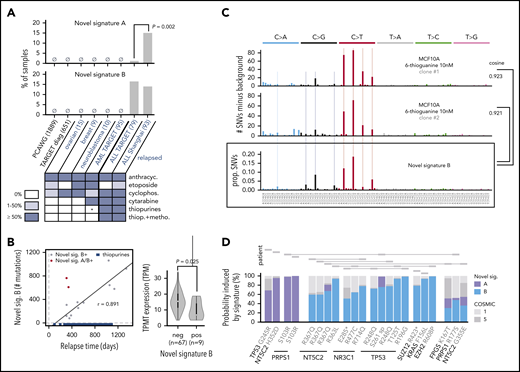

Candidate mutagenic agents causing novel signatures

To identify mutagenic chemotherapies causing the novel signatures, we queried each signature for its presence in WGS data from: (1) 1889 adult tumors at diagnosis from Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes45 spanning 36 cancer types; (2) 651 pediatric cancers at diagnosis (ALL, acute myeloid leukemia [AML], neuroblastoma, Wilms tumors, and osteosarcoma) from National Cancer Institute–TARGET (Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments)43 ; (3) 15 relapsed ovarian cancers46 ; (4) 9 relapsed breast cancers47 ; (5) 10 relapsed neuroblastomas from TARGET; (6) 95 relapsed AMLs from TARGET; and (7) 79 additional relapsed ALLs from TARGET (Figure 5A). None of the diagnosis samples harbored the novel signatures, nor did any relapsed ovarian, breast, neuroblastoma, or AML samples.

Causes and consequences of the 2 novel mutational signatures. (A) Detection of novel signatures in additional cohorts of primarily diagnosis (black text) or relapse (blue text) samples. Number of tumor samples is indicated in parentheses. Heatmap at bottom depicts percentage of patients receiving indicated therapy in the relapsed cohort. anthracyc., anthracyclines; cyclophosph., cyclophosphamide; thiop., thiopurines; metho., methotrexate. P is by Fisher’s exact test. PCAWG, Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes. Shanghai refers to our cohort. Asterisk indicates that a subset of relapsed AMLs from TARGET (14 of 95) received thiopurines but only for ≤2 weeks, an insufficient time to generate the signature as shown in panel B, as part of the CCG-2961 trial. (B) Left, correlation between relapse time and novel signature B strength. Blue indicates approximate time periods of thiopurine treatment in 17 cases for which detailed clinical information was available; treatment end is indicated as 3 years as all patients ended treatment by that time (see supplemental Methods); r is Pearson correlation coefficient excluding novel signature A/B–positive (double-positive) cases (2 red points), which are also excluded from the indicated regression line. Right, TPMT expression based on RNA-Seq of diagnosis samples of novel signature B–negative or signature B–positive patients; P value is by 2-sample Student t test. (C) Mutational spectra of two MCF10A single-cell clones after treatment with 6-thioguanine 10 nM for 7 weeks. The y-axis represents the number of mutations in the treated clone minus the background mutation spectra averaged from 2 untreated single-cell clones. Bottom shows novel signature B; “cosine” indicates cosine similarity for indicated comparisons, and "prop. SNVs" indicates proportion of SNVs. Light vertical lines mark novel signature B–preferred trinucleotide mutation types for comparison. (D) Relapse-specific pathogenic mutations with ≥50% probability to be caused by the novel signatures at relapse. The y-axis represents the probability each variant was caused by a given signature, and each variant represents a relapse-specific mutation detected in a specific patient. Mutations in the same patient are shown as rectangles joined by lines (top). “S261 sp” represents a TP53 variant (chr17:7 577 157, T>G) likely affecting splicing, and the T125T variant also affects splicing.

Causes and consequences of the 2 novel mutational signatures. (A) Detection of novel signatures in additional cohorts of primarily diagnosis (black text) or relapse (blue text) samples. Number of tumor samples is indicated in parentheses. Heatmap at bottom depicts percentage of patients receiving indicated therapy in the relapsed cohort. anthracyc., anthracyclines; cyclophosph., cyclophosphamide; thiop., thiopurines; metho., methotrexate. P is by Fisher’s exact test. PCAWG, Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes. Shanghai refers to our cohort. Asterisk indicates that a subset of relapsed AMLs from TARGET (14 of 95) received thiopurines but only for ≤2 weeks, an insufficient time to generate the signature as shown in panel B, as part of the CCG-2961 trial. (B) Left, correlation between relapse time and novel signature B strength. Blue indicates approximate time periods of thiopurine treatment in 17 cases for which detailed clinical information was available; treatment end is indicated as 3 years as all patients ended treatment by that time (see supplemental Methods); r is Pearson correlation coefficient excluding novel signature A/B–positive (double-positive) cases (2 red points), which are also excluded from the indicated regression line. Right, TPMT expression based on RNA-Seq of diagnosis samples of novel signature B–negative or signature B–positive patients; P value is by 2-sample Student t test. (C) Mutational spectra of two MCF10A single-cell clones after treatment with 6-thioguanine 10 nM for 7 weeks. The y-axis represents the number of mutations in the treated clone minus the background mutation spectra averaged from 2 untreated single-cell clones. Bottom shows novel signature B; “cosine” indicates cosine similarity for indicated comparisons, and "prop. SNVs" indicates proportion of SNVs. Light vertical lines mark novel signature B–preferred trinucleotide mutation types for comparison. (D) Relapse-specific pathogenic mutations with ≥50% probability to be caused by the novel signatures at relapse. The y-axis represents the probability each variant was caused by a given signature, and each variant represents a relapse-specific mutation detected in a specific patient. Mutations in the same patient are shown as rectangles joined by lines (top). “S261 sp” represents a TP53 variant (chr17:7 577 157, T>G) likely affecting splicing, and the T125T variant also affects splicing.

However, novel signature B was also detected in 13 of 79 relapsed ALLs from TARGET, implicating a shared therapy given to both ALL cohorts (Figure 5A). Several ALL drugs are unlikely candidate causes because they do not induce point mutations, including glucocorticoids,48,49 l-asparaginase,48 and vincristine.48,50,51 Among the DNA-damaging therapeutic agents given to both ALL cohorts,34,52 thiopurine treatment (alone or combined with MTX) was a plausible cause of novel signature B, because thiopurines were given primarily to patients with ALL but not those with other cancers. Thiopurines induce C>T mutations,53 consistent with the primarily C>T profile of novel signature B (Figure 4B). More strikingly, the number of novel signature B–induced mutations in novel signature B–positive cases correlated with relapse time from the start (3-4 months after diagnosis) to the end (3 years) of thiopurine treatment (r = 0.891) (Figure 5B), unlike the other mutagenic agents (ie, daunorubicin, cyclophosphamide) that are given primarily during the first 4 to 6 months.34 We note that 2 outlier patients had higher-than-expected novel signature B mutations given their relapse time. Both patients uniquely harbored both novel signatures A and B; they may have been hypersensitive to chemotherapy and were thus excluded from the correlation analysis. Expression of TPMT, encoding thiopurine S-methyltransferase which inactivates thiopurines,54 was lower in novel signature B–positive patients (P = .025), suggesting that these cases poorly inactivate thiopurines.

Novel signature B had an apparent mutation rate of 0.77 mutation per day (Figure 5B), well above ubiquitous processes such as clock-like signatures 1 (0.17 mutation per day) and 5 (0.11 mutation per day) (supplemental Figure 12); this finding suggests that chemotherapy elevates the basal mutation rate in ALL, facilitating clonal evolution. Interestingly, novel signature A did not increase with relapse time, suggesting that the causative therapeutic agent was given up-front but not later.

Novel signature A, in contrast to B, was present in only 1 of 79 patients with relapsed ALL in the TARGET cohort (1% vs 15% in our cohort; P = .002), suggesting that the causative therapeutic agent was given to patients in our cohort but not in the TARGET cohort; etoposide was one possibility (Figure 5A). Alternatively, the causative therapeutic agent was given to both cohorts but in different order, combination, or dosing. The enrichment of novel signature A in hyperdiploid cases may be due to increased sensitivity of hyperdiploid ALL to certain chemotherapies.55

The 2 novel signatures were dissimilar from the 53 recent mutagen signatures, including various chemotherapies, from Kucab et al56 (cosine similarity <0.35). The study did not analyze thiopurines, MTX, cytarabine, or anthracyclines (Figure 5A) but did analyze cyclophosphamide (cosine similarity <0.15 to the novel signatures, thus ruling it out) and etoposide. Etoposide yielded no signature, possibly due to the short-term in vitro exposure used (≤24 hours), which would not have yielded our novel signatures because they have mutation rates of ∼1 mutation per day or less (supplemental Figure 12).

Experimental identification of thiopurines as the cause of novel signature B

To test whether thiopurines are the cause of novel signature B as hypothesized, our initial experiment involved treating the ALL cell line REH with thiopurines (6-mercaptopurine or 6-thioguanine) for 3 months with stepwise increasing doses from 0.6 to 120 μM. This was followed by WGS of 7 thiopurine-resistant single-cell clones and the REH untreated bulk control cells to identify single-cell clone-specific SNVs (supplemental Figure 13). However, mutations in single-cell clones largely arose from selection of preexisting resistant clones, as most of them (75%) were shared among multiple clones rather than private, whereas drug treatment would be expected to cause unique private mutations in each clone. The mutational spectrum in REH-resistant clones was similar to COSMIC signature 26 (cosine similarity >0.93), indicative of mismatch repair deficiency, consistent with reported MLH1 inactivation in REH cells.57 The REH spectrum was dissimilar to novel signature B (cosine similarity <0.3), likely due to the selection of resistant clones that may inactivate thiopurine-induced mutagenesis such as through drug efflux.58

REH cells59 and most other ALL cell lines were derived from relapsed leukemia60-62 and are thus more likely to harbor drug-resistant clones precluding thiopurine-induced mutagenesis, suggesting other experimental models may be preferable for testing whether thiopurines cause novel signature B. We therefore next tested whether thiopurines induce novel signature B using the noncancerous MCF10A cell line, derived from human mammary epithelial cells; this line was successfully used to identify the mutational signature for cisplatin,22 a signature that has been validated in multiple cancer types.22,46,63-65 We also used a lower thiopurine treatment dose (10 nM), which inhibited MCF10A growth ∼20% but allowed continuous proliferation, to avoid selecting resistant clones incapable of drug-induced mutagenesis.22,66 MCF10A cells were treated with 6-thioguanine for 7 weeks, and we isolated 2 single-cell clones for WGS, along with 2 untreated single-cell clones cultured during the same period, to subtract the background mutation rate,56 a cisplatin-treated positive control clone, and the bulk untreated cell line. Unlike the REH experiment, only 3% of mutations found in single-cell clones were shared among multiple clones, and 97% were private, indicating successful mutagenesis rather than selection (supplemental Figure 14A). Furthermore, the mutational spectrum of each MCF10A 6-thioguanine–treated clone closely resembled novel signature B (cosine similarity 0.923 and 0.921 in the 2 clones) after subtracting the background signature (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 14B), whereas none of the COSMIC mutational signatures resembled the MCF10A 6-thioguanine spectra (cosine similarity <0.9). Furthermore, the cisplatin-treated–positive control clone also closely matched the published22 cisplatin signature (cosine similarity, 0.965), indicating the robustness of the experimental system used. Together, these data show that thiopurines are indeed the cause of novel signature B.

Chemotherapy-induced drug resistance mutations

To determine whether the 2 novel signatures caused driver mutations, we used an approach67 that we have used previously65 (supplemental Methods). Two example calculations, using a likely novel signature A– or signature B–induced drug resistance mutation, are shown in supplemental Figure 15. We focused on relapse-specific mutations with >50% probability of induction by the novel signatures.

Four relapse-specific driver mutations had >50% probability of induction by novel signature A (Figure 5D), including two PRPS1 S103R mutations, one NT5C2 H352D mutation, and one TP53 G245R mutation. The two PRPS1 S103R variants occurred at G[C>G]C, a novel signature A hotspot (Figure 4B), with probabilities of 96.6% and 99.9% of induction by novel signature A; one is shown in detail in supplemental Figure 15A. Mutations at PRPS1 S103 confer thiopurine resistance,5 although S103R has not been reported. Interestingly, PRPS1 mutations were enriched in novel signature A–positive patients (67% of PRPS1-mutant patients had novel signature A compared with 13% novel signature A positivity among the remaining patients; Fisher’s exact test, P = .058); TARGET relapses had no PRPS1 mutations and only one novel signature A–positive patient (Figure 5A), suggesting a link between PRPS1 mutations and novel signature A.

Novel signature B likely caused an NT5C2 R363L variant with 93.4% likelihood and also induced three NT5C2 R367Q variants, which cause thiopurine resistance,32 at novel signature B’s hotspot T[C>T]G (Figure 4B), with probabilities of 67.3%, 59.6%, and 59.5% (Figure 5D). (A fourth R367Q patient had a probability of 42.2%.) Four of the 6 patients with R367Q mutations (67%) bore novel signature B, compared with only 10% novel signature B positivity in the remainder of the study cohort (P = .003) (supplemental Figure 16A-B); likewise, 2 of 3 patients with R367Q (67%) mutations in the TARGET cohort bore novel signature B compared with 14% in the rest of the TARGET cohort (P = .069), suggesting that this NT5C2 hotspot mutation7 is frequently thiopurine induced, which is followed by selection by thiopurine treatment. Interestingly, most NT5C2 non-R367Q mutations occurred in novel signature B–negative patients and, unlike R367Q, did not occur at novel signature B–preferred trinucleotides (supplemental Figure 16B-C). This finding indicates that although R367Q is likely treatment induced, most other NT5C2 mutations are caused by other mutational processes. In addition, novel signature B likely caused three NR3C1 mutations (51.0%-78.0% probability) that confer glucocorticoid resistance (Figure 2A) and five loss-of-function68-72 TP53 mutations (72.4%-98.5% probability) (Figure 5D). The TP53 R196G variant, which causes chemotherapy resistance (Figure 2D), was found at the C[C>G]G novel signature B–preferred context (supplemental Figure 15B) and had a 98.5% probability of induction by the signature. Thus, the therapy causing novel signature B (thiopurines) may mutate genes involved in response to diverse drug classes.

Overall, 18 (46%) of 39 relapse-specific sequence mutations in NT5C2, PRPS1, NR3C1, and TP53 had their most likely cause as one of the novel signatures. Furthermore, 34% of relapse-specific SNVs in these 4 genes were C>G mutations, which are enriched in the novel signatures (Figure 4B), whereas only 10% of all coding SNVs were C>G (Fisher’s exact test, P = 2.3 × 10−4). The novel signatures also likely induced mutations affecting the key pathways identified in our study (Figure 1C; supplemental Figure 2), including Polycomb repressive complex 2 tumor-suppressive components73 SUZ12 and EZH2, and an activating KRAS F156L74 variant (Figure 5D).

Clonal evolution patterns cohort-wide

We analyzed clonal evolution patterns across the cohort by two-dimensional VAF analysis of diagnosis vs relapse samples in each patient (supplemental Note 1). This analysis revealed that all patients had diagnosis-specific variants lost at relapse, indicating branched rather than linear evolution.14 Eighty percent of relapses were seeded by a single dominant “sweeping” clone (as evidenced by high-VAF relapse-specific mutations) (supplemental Figure 17A) accompanied by its descendant subclones in 52% of cases. In 60% of all patients, the lineage of the sweeping clone could be traced to a subclone present at diagnosis; in the remaining cases, such a subclone was not detected at diagnosis, which could be due to low cellular fraction of a subclone beyond the detectability afforded by capture sequencing, or a lineage from an ancestral clone containing only the founder mutations. In 19% of cases, relapse was seeded by multiple clones, as in BCR-ABL1+ example case SJALL040464, in which a ZNF532-mutant clone at diagnosis survived to relapse (minor clone) along with a major clone that harbored ABL1 T315I (kinase inhibitor–resistant).13 Finally, a single case had survival of an ancestral clone without acquisition of additional mutations. These latter 2 groups (multiclonal and ancestral relapse) correlated with very early relapse (P = .02) (supplemental Figure 17B).

We next evaluated cohort-wide whether mutations in the 6 genes involved in drug metabolism or binding (NT5C2, PRPS1, PRPS2, FPGS, NR3C1, and NR3C2) evolved in the sweeping clone or its later descendant subclones in 31 relapses acquiring these mutations (supplemental Figure 17C). Thirty (68.2%) of 44 mutations were subclonal at relapse, suggesting that most were acquired after the sweep; in 6 of 31 samples, this involved convergent evolution of NT5C2, PRPS1, or PRPS2 variants in which multiple clones independently mutated the same resistance gene. Because NT5C2 and PRPS1 mutations are activating,5,7,32 a single clone would be unlikely to acquire more than one such variant. Indeed, single-cell sequencing of 14 SNVs from 56 individual cells from SJALL043552 at relapse, which acquired two subclonal PRPS2 variants (A175T and A134T), revealed that the PRPS2 mutations were in different subclones (supplemental Figure 18). PRPS1 and PRPS2 are highly homologous,75 and the PRPS2 A175T variant may function similarly to PRPS1 relapse-specific variants at R177S (this cohort) and G174E (previously reported).5 Interestingly, no patient had subclonal NT5C2-PRPS1 pairs of mutations co-occurring even though NT5C2-NT5C2 and PRPS1-PRPS1 convergent cases occurred, suggesting different mutational causes and/or biological functions of these genes in drug resistance.5,32 Five cases had mutations in multiple genes, with evidence for co-occurrence of multiple mutations conferring resistance to 2 drug classes within the same clone: glucocorticoids and 6-mercaptopurine in 3 cases, and MTX and 6-mercaptopurine in 1 case (supplemental Figure 19). Furthermore, NT5C2, PRPS1, and PRPS2 mutations were never detectable at diagnosis despite up to >50 000× sequencing depth, consistent with previous studies.5,10 Together, these data reinforce the notion that clones with acquired resistance mutations can appear after diagnosis, during treatment (“on-treatment acquired”) (Figure 3A).

Clonal evolution of serial samples

We tracked clonal evolution using targeted ultra-deep sequencing at median 3669× coverage across 208 serial bone marrow samples from 16 patients, with ≥7 samples per patient (Figure 1B); this evaluation is shown in Figure 6 and supplemental Figure 20. The data were analyzed by using a site-specific error model to distinguish low-frequency variation from sequencing artifacts (supplemental Methods). The median time interval of sample collection was 74 days. Clonal evolution schemes were determined with manual analysis and corroboration with automated analysis based on CALDER76 (supplemental Figure 17D). The current discussion focuses on patients with multiple relapses or where bone marrow samples between diagnosis and relapse had detectable mutations, which could inform the timing of resistant clone appearance.

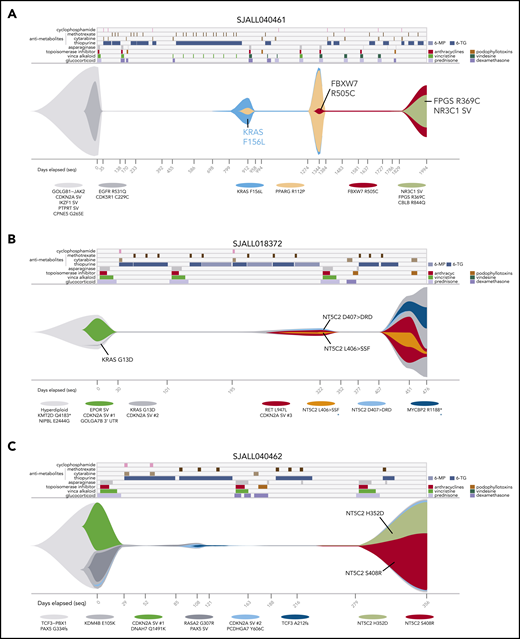

Serial sample analysis reveals dynamics of resistant clone evolution. Graphical representations (“fish plots”) of clonal evolution shaped by chemotherapy based on ultra-deep sequencing in patients SJALL040461 (A), SJALL018372 (B), and SJALL040462 (C). Treatment history is shown at the top, with drug treatment periods indicated by colors. 6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine; 6-TG, 6-thioguanine. MTX was given weekly during maintenance and is only shown at the beginning of a regimen during maintenance. Clonal evolution is shown in the middle with the vertical axis representing proportion of cells; normal cells are represented by white space. ALL clones are indicated in colors by representative mutations listed below. The minimum tumor purity values (thin line) indicate no detectable ALL cells by ultra-deep sequencing, and their clonal compositions at these times are inferred. Days from diagnosis are indicated at the bottom, with tick marks indicating time points at which samples were sequenced. Samples sequenced by WGS are indicated by black text and tick marks on x-axes, whereas samples with targeted deep sequencing only are shown in gray. In panels B and C, multiple independent CDKN2A deletions are indicated by CDKN2A SV #1, SV #2, and so forth. Variants with alternative possible clonal parentage are indicated by blue asterisks (B). In panel B, the VAF of NT5C2 D407 > DRD at day 322 is 0.007%, but it is shown as larger to enable visualization. In panel C, the surviving clones at days 108 and after are descended from the KMD4B (gray) clone; the KDM4B descendant PCDHGA7 (light-blue) clone and its descendants are dominant at day 356.

Serial sample analysis reveals dynamics of resistant clone evolution. Graphical representations (“fish plots”) of clonal evolution shaped by chemotherapy based on ultra-deep sequencing in patients SJALL040461 (A), SJALL018372 (B), and SJALL040462 (C). Treatment history is shown at the top, with drug treatment periods indicated by colors. 6-MP, 6-mercaptopurine; 6-TG, 6-thioguanine. MTX was given weekly during maintenance and is only shown at the beginning of a regimen during maintenance. Clonal evolution is shown in the middle with the vertical axis representing proportion of cells; normal cells are represented by white space. ALL clones are indicated in colors by representative mutations listed below. The minimum tumor purity values (thin line) indicate no detectable ALL cells by ultra-deep sequencing, and their clonal compositions at these times are inferred. Days from diagnosis are indicated at the bottom, with tick marks indicating time points at which samples were sequenced. Samples sequenced by WGS are indicated by black text and tick marks on x-axes, whereas samples with targeted deep sequencing only are shown in gray. In panels B and C, multiple independent CDKN2A deletions are indicated by CDKN2A SV #1, SV #2, and so forth. Variants with alternative possible clonal parentage are indicated by blue asterisks (B). In panel B, the VAF of NT5C2 D407 > DRD at day 322 is 0.007%, but it is shown as larger to enable visualization. In panel C, the surviving clones at days 108 and after are descended from the KMD4B (gray) clone; the KDM4B descendant PCDHGA7 (light-blue) clone and its descendants are dominant at day 356.

Sequential acquisition of multiple drug-resistant mutations was prevalent in cases with multiple relapses as exemplified by patient SJALL040461, who had 23 serial samples, including 3 successive relapses (Figure 6A). KRAS F156L, which was likely induced by novel signature B (Figure 5D), appeared at first relapse (day 912) from a subclone present at 74% cancer cell fraction at diagnosis. The KRAS mutation may have promoted resistance to MTX9,74 or glucocorticoid treatment.77 A second relapse occurred from a PPARG-mutant clone descended from the KRAS clone. At third relapse, the patient acquired co-occurring resistance mutations in FPGS (R369C) and an NR3C1 SV (exon 1-2 one-copy deletion). Throughout disease progression, the mutation burden caused by novel signature B increased from 0 at diagnosis, to 945 at the second relapse, and then 1447 at the third relapse. (The first relapse had only targeted sequencing, but not WGS, and signature analysis could not be performed.) Thus, multiple resistance mutations can be acquired sequentially, possibly through chemotherapy-induced mutagenesis.

This patient also showed that multiple resistance mutations targeting different drug classes can be acquired sequentially through successive relapses; that is, KRAS followed by FPGS and NR3C1 (Figure 6A). Two additional cases with multiple relapses exhibited the same pattern (ie, NR3C1 followed by TP53, and MSH2 followed by TP53) (supplemental Figure 20A). This pattern is consistent with the multistep resistance acquisition model and suggests that multiple resistance mutations are necessary for multidrug-resistant relapse in some patients. Indeed, 17% of patients acquired multiple mutations in the 12 resistance genes at relapse, generally targeting different drug classes (Figure 1D; supplemental Figure 2).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that chemotherapy itself may induce drug resistance mutations, which has been suggested by others based on genomic analysis of cisplatin-treated cell cultures66 and the finding that temozolomide can induce driver (although not necessarily resistance-causing) mutations in glioblastoma.78

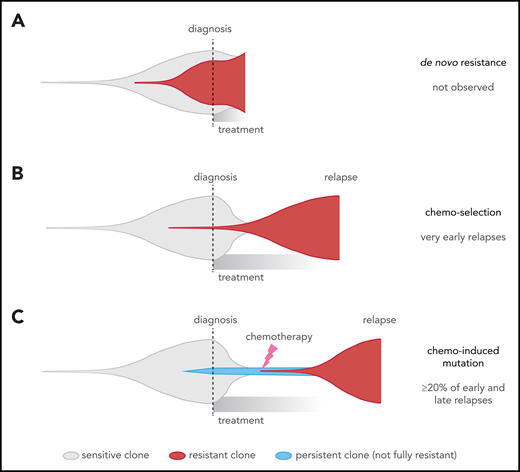

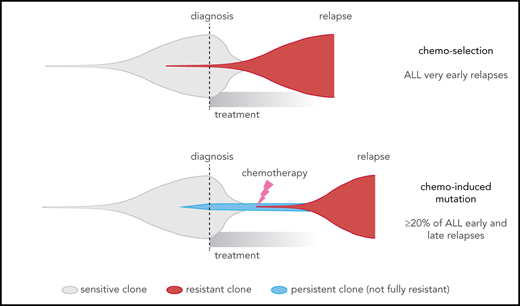

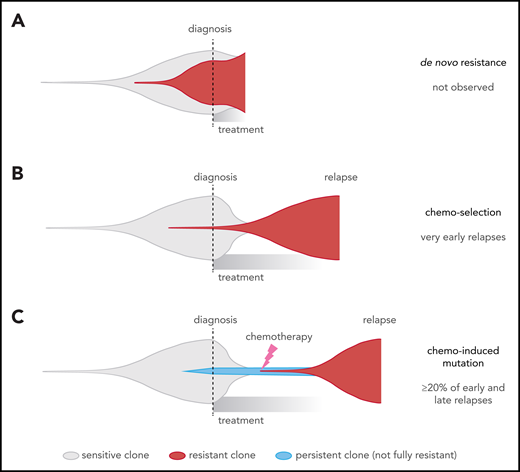

This contrasts with 2 widely recognized forms of cancer drug resistance, namely: (1) de novo resistance, in which most cancer cells are drug resistant up-front14 (Figure 7A), which is rare in ALL79 and was not observed in our cohort (all cases had ≥2 month remission); and (2) acquired resistance from a preexisting drug-resistant clone11,12 (Figure 7B), which may explain very early relapses, which are dominated by MLL (KMT2A)-rearranged and Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, based on our model (Figure 3A-B). By contrast, early and late relapses could be due to either: (1) a preexisting resistant clone growing slower than expected; or (2) on-treatment acquisition of resistant clones, including chemotherapy-induced resistance mutations, as 32% of early and late relapses harbored the novel signatures that were usually found in the dominant relapse clone (Figure 7C; supplemental Figure 10). Enrichment of resistance mutations in these 2 groups, and high-depth sequencing of serial samples, also support the latter scenario in many patients. This may occur through a 2-step selection of a persister38 clone, which survives initial treatment and later gives rise to the true resistant clone. Thus, resistance is not a foregone conclusion and may be preventable through altered up-front treatment strategies.

Comparison of different clonal evolution models leading to relapse. Clones are represented as in the fish plots in Figure 6, and time goes from left to right from time of disease initiation to relapse. Clone sizes are represented in the vertical direction. Chemotherapy-sensitive clones are indicated in gray, chemotherapy-resistant in red, and persistent clones (able to survive but not proliferate during chemotherapy) in blue. The time of diagnosis and treatment commencement are indicated by a dotted line. (A) The de novo resistance scenario, in which most cells are chemoresistant up-front and remission is never achieved; this was not observed in our cohort. (B) The chemo-selection scenario, in which a minor drug-resistant subclone survives chemotherapy and leads to relapse after an initial remission. Our mathematical modeling suggests that very early relapses (<9 months) are likely due to this mechanism. (C) The chemo-induced mutation scenario, in which no fully resistant subclone is present at the time of diagnosis. The drug-resistant subclone is derived from a population of cells that persisted (survived) during chemotherapy treatment but was not fully drug resistant because it could not actively proliferate sufficiently to cause relapse. This is supported by mutational signature and mathematical modeling in later relapse groups (specifically, the early and late relapse groups).

Comparison of different clonal evolution models leading to relapse. Clones are represented as in the fish plots in Figure 6, and time goes from left to right from time of disease initiation to relapse. Clone sizes are represented in the vertical direction. Chemotherapy-sensitive clones are indicated in gray, chemotherapy-resistant in red, and persistent clones (able to survive but not proliferate during chemotherapy) in blue. The time of diagnosis and treatment commencement are indicated by a dotted line. (A) The de novo resistance scenario, in which most cells are chemoresistant up-front and remission is never achieved; this was not observed in our cohort. (B) The chemo-selection scenario, in which a minor drug-resistant subclone survives chemotherapy and leads to relapse after an initial remission. Our mathematical modeling suggests that very early relapses (<9 months) are likely due to this mechanism. (C) The chemo-induced mutation scenario, in which no fully resistant subclone is present at the time of diagnosis. The drug-resistant subclone is derived from a population of cells that persisted (survived) during chemotherapy treatment but was not fully drug resistant because it could not actively proliferate sufficiently to cause relapse. This is supported by mutational signature and mathematical modeling in later relapse groups (specifically, the early and late relapse groups).

Shortcomings of our mathematical modeling include our inability to determine the following: (1) resistant clone doubling times in T-ALL, as only 2 patients with T-ALL had sufficient longitudinal MRD data; (2) how doubling times vary between B-ALL subtypes; and (3) variability in doubling times and cell cycle times in B-ALL.36 To partly mitigate the latter 2 concerns, we analyzed a range of B-ALL potential doubling times (Figure 3B) published previously.36 It would be valuable for future studies to determine cell cycle and doubling times within individual patients and perform modeling on a patient-by-patient basis.

The mechanisms by which thiopurines cause novel signature B are of interest for future studies. The transcription strand bias of novel signature B, indicating mutations originating with guanine (supplemental Figure 9B), is consistent with a thiopurine (6-thioguanine) incorporated into DNA, although the mechanisms causing preference for the CpG context are unclear. Interestingly, the C>T and C>G profiles in novel signature B mirror one another with preference for the same trinucleotides (Figure 4B) in a way similar to APOBEC signatures 2 and 13.80 The C>T mutations may result from DNA replication after thiopurine incorporation into DNA,53 whereas C>G mutations may result from other mechanisms. The positive correlation between novel signature B and structural variants (supplemental Figure 11) is consistent with the known ability of thiopurines to cause structural rearrangements.81,82

The extent of chemotherapy-induced resistance mutations may have been underestimated in the current study, because cases in which the novel signatures induce resistance mutations very quickly would lack detectable novel signature signal, as the resistance mutation could shut off or alter chemotherapy-induced mutagenesis.5,10,58 In support of this theory, 2 patients had relapse-specific mismatch repair gene mutations (PMS2 R294P and MSH2 R711P) at the C>G novel signature B–preferred contexts C[C>G]G and T[C>G]G (Figure 4B), which are rarely mutated by other signatures.39 However, these patients lacked detectable novel signature B, perhaps due to the dramatic number of subsequent mutations related to mismatch repair deficiency (Figure 4A), thereby drowning out novel signature B signal. Thus, it is possible that the novel signatures are only detectable in patients in whom chemotherapy-induced mutagenesis continued for a longer period of time or where other mutational processes did not supersede novel signature signal.

Our findings suggest use of “precision” approaches to improve treatment of relapsed ALL. For example, patients with high-risk ALL could be monitored periodically during remission for early detection of drug resistance mutations, perhaps using high-depth sequencing of DNA from blood or other tissue. The optimal interval for monitoring would be every 20 to 30 days, as we found that ALL-specific mutations can be detected at a median of 42 days before overt relapse by using high-depth sequencing of our serial bone marrow samples (supplemental Figure 21). In addition, CD19/CD22–targeted immunotherapies such as CAR T cells and bispecific antibodies83,84 may be effective in patients with relapsed B-ALL with chemoresistance mutations, and mismatch repair-deficient relapses may be sensitive to other immunotherapies due to their high mutation burden85-87 (Figure 4A).

Parent(s)/guardian(s) of the patients provided informed consent for clinical trial participation, tissue banking, and future research. All analyses were approved by the institutional review boards of Shanghai Children's Medical Center, the Second Hospital of Anhui Medical University, and the Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital in Tianjin.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for Kevin Shannon and Anica Wandler for their valuable feedback. They acknowledge William Evans for helpful discussions on causes of novel signatures, and thank Yung-Li Yang for valuable feedback. The authors also acknowledge Gerard Zambetti for feedback on p53 analysis, the International Cancer Genome Consortium and The Cancer Genome Atlas for access to Pan-Cancer Analysis of Whole Genomes data, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) for use of the TARGET datasets.

This research was supported, in part, by Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA021765 from the NIH/NCI and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. This study was also supported, in part, by Viva China Children’s Cancer Foundation Ltd, Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center (16CR2024A), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31530017, 81421002, 81670174, 81670136, and 81470313), the China National Children’s Medical Center (Shanghai), grants from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2016-I2M-1-002 and 2017-I2M-1-015), and the Science and Technology Commission of Pudong New Area Foundation (PKJ2014-Y02).

Authorship

Contribution: Jinghui Zhang, J.J.Y., J.R.D., C.-H.P., B.L., and S.S. initiated and designed the study; B.L., S.S., L. Ding, T.W., L.Y., Jie Zhao, Jingliao Zhang, Y.Z., J.C., and H.-Y.S. acquired and processed patient specimens and clinical information; B.L., J.J.Y., and Jinghui Zhang supervised the study; B.L., Yongjin Li, S.W.B., X.M., K.S., Yu Liu, N.W., D.A.F., K.X., Yanling Liu, L.T., K.H., M.N.E., M.R., C.C., X. Zhu, X. Zhou, E.S., and J.T. performed the analysis under the supervision of Jinghui Zhang; M.A.M. performed analysis under supervision of B.J.R.; H.Z., T.-N.L., L. Du, L. Dong, H.L., H.L.M., and F.Y. conducted functional experiments under the supervision of J.J.Y., B.-B.S.Z., and J.E.; L.B.A. provided guidance on mutational signature analysis; H.S. and L.S. oversaw genomic sequencing; capture sequencing was designed by H.L.M., Y.S., and J.E; and the manuscript was written by Jinghui Zhang, S.W.B., X.M., B.L., Yongjin Li, Yu Liu, Yanling Liu, K.S., J.J.Y., B.-B.S.Z., and C.-H.P. and was reviewed and edited by all authors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.J.R. is a consultant at and has ownership interest in (including stock and patents) Medley Genomics. H.S. and L.S. are employees of WuXi NextCODE Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jinghui Zhang, Department of Computational Biology, MS 1135, Rm IA6038, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, Memphis, TN 38105-3678; e-mail: jinghui.zhang@stjude.org; Jun J. Yang, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, MS 313, Rm I5104, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, Memphis, TN 38105-3678; e-mail: jun.yang@stjude.org; Ching-Hon Pui, Department of Oncology, MS 260, Rm C6056, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, Memphis, TN 38105-3678; e-mail: ching-hon.pui@stjude.org; and Bin-Bing S. Zhou, Key Laboratory of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, 8th Fl, Comprehensive Medical and Research Bldg, Shanghai Children's Medical Center, 1678 Dongfang Rd, Shanghai, China; e-mail: zhoubinbing@scmc.com.cn.

References

Author notes

B.L., S.W.B., X.M., S.S., Y.Z., and Y. Li contributed equally to this study.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

![Relapse-enriched somatic variants in pediatric ALL. (A) ALL subtypes of the patient cohort. The number of cases in each subtype and in B- or T-lineage is labeled in the outer and the inner circles, respectively. Subtypes of singleton cases are binned to B/Other (IGH-MYC and hypodiploid) or T/Other (HOXA). D, diagnosis; R, relapse. (B) Schematic showing sequencing performed and number of patients (n) sequenced with each platform. (C) Pathways mutated among shared variants (diagnosis and relapse [D+R]) compared with relapse-specific variants (R); pathways are defined in supplemental Table 5. Color indicates mutation type identified in a single patient; box indicates pathways enriched at relapse. Slice width represents the proportion of patients with mutation of at least 1 gene in indicated pathway. (D) Heatmap of significantly mutated genes and known driver genes across the cohort, with genes in rows and patients in columns. The 12 genes at top are those enriched specifically among relapse-specific variants (supplemental Methods), and genes in the bottom portion are frequently present at both diagnosis and relapse. At right, a bar plot of the percentage of patients mutated for each gene is shown, along with the pathway to which the gene belongs. Gray indicates that the mutation is shared at diagnosis and relapse (D+R), red indicates relapse-specific (R), and blue indicates diagnosis-specific (D). Subtypes and B- vs T-lineage are indicated at top. CDKN2A mutations occurred in 49% of samples, which is above the axis limit.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/135/1/10.1182_blood.2019002220/3/m_bloodbld2019002220f1.png?Expires=1769905087&Signature=ldIR2vZ3VTMHrY8V5V~RFojWRN9w0E4arAp0ujEgC2KUso9R7sSSZgkWYRnVsapCK5tOLjnIupxp5BFLuGvUlbPlEPZGV~SqImMppCM8F4dcoExbhQI8pa~-e1Y6rJr7zlO1mZevYyKpJRiiLChnA76Qt5S01L~JriQTy83QfwEtLANpttEfxfiKkCRv2dj3Nwqf6EBaF8mEbtC7Fc3RHrmBcIfE9h8IYU3FYuoDjIwtECQybb-uHxXmRsqIsHyuXGmIHmpfffDrASie19IhkKS5MdVAONhaMMkvm4vjplvMY1OEe~UCAUphNKdsdJxQWmZmaTEz7H7BnRBljmyshA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Functional characterization of relapse-specific mutations. (A) Top, relapse-specific NR3C1 mutation locations within the NR3C1 protein, with the x-axis indicating amino acid position. Bottom, their effects on NR3C1 transcriptional activator activity (left) and ALL sensitivity to glucocorticoids (right). Left, mutant, wild-type (WT), and empty vector (EV) transcription activator activity was measured in HEK293T cells by using the reporter gene assay. Mutations are grouped and color-coded according to their locations in protein domains. Right, glucocorticoid sensitivity (ie, dose–response curve) was measured by using cell viability after treatment with prednisolone for 72 hours in ALL cell line REH expressing WT or mutant NR3C1 (color-coded according to protein domain), using the MTT assay. The y-axis represents percent cell viability compared with untreated control. Error bars indicate standard error. (B) Top, FPGS relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, their effects on polyglutamation enzymatic activity using MTX as the substrate. Purified mutant and WT FPGS were tested at 3 different amounts (5 ng, 2.5 ng, or 1.25 ng) in triplicate, and the enzymatic activity was relative to the activity of the WT at 5 ng. The first 2 columns represent controls with no MTX or FPGS. Error bars represent standard error. (C) Top, NT5C2 relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, cell viability of REH or Nalm6 cells treated with 6-thioguanine (6-TG, left) or 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP, right) in cells expressing indicated NT5C2 mutations (or WT NT5C2 or uninfected control [-]). Error bars represent standard deviation. (D) Top, TP53 relapse-specific mutations. Bottom, functional validation of TP53 R248Q and R196G. Nalm6 cells underwent TP53 knockout (KO) by CRISPR and were reintroduced with TP53 WT, R196G, or the known hotspot R248Q mutant. Left, cell viability in response to idarubicin and vincristine treatment. Right, fold change in proportion of Annexin V–positive apoptotic cells (top) and in proportion of EdU+ cells in S phase (bottom; values <1.0 indicate G1/S checkpoint arrest induced by functional p53 in response to treatment), compared with untreated controls, after treatment with 1 µM (top) or 0.01 µM (bottom) idarubicin for 24 hours. Error bars represent standard deviation. Dotted line in right panels represents 1.0. Protein domains are as reported on pecan.stjude.cloud (A,D), National Center for Biotechnology Information (B), or Dieck et al32 (C).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/135/1/10.1182_blood.2019002220/3/m_bloodbld2019002220f2.png?Expires=1769905087&Signature=k7vA7aKK1feZRB0tgDSeg5swoQM1BRGJxT-kxPtoT49Pp-F4vbMKfN5a5MNGuhTT5uqNFvMTYN4Q1GTOdbAA2ttwg337N8S8yS2xr9YDIkv2Yc2b7QsNwNT5G9TakDnmYC3KrouN-~vYMCRPccZ1lQFdfxlXHkbKyn8r-tfo83HisxiRSRrvkYfOMGRL5tJVjxAhkoXMT35yMlhmC~rl8hx1BHRcluiWSOEalKmelWXhHKpSzNhxEFliOVMYHTx8fsP9CVb1UPiZHMuc17XgzH1W81s46ZJL38yjQdkaaBsnfBlbdthBt4~jtlPojdVNtrKhkD3mCoA2ntRQVmtn8g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Relapse-enriched somatic variants in pediatric ALL. (A) ALL subtypes of the patient cohort. The number of cases in each subtype and in B- or T-lineage is labeled in the outer and the inner circles, respectively. Subtypes of singleton cases are binned to B/Other (IGH-MYC and hypodiploid) or T/Other (HOXA). D, diagnosis; R, relapse. (B) Schematic showing sequencing performed and number of patients (n) sequenced with each platform. (C) Pathways mutated among shared variants (diagnosis and relapse [D+R]) compared with relapse-specific variants (R); pathways are defined in supplemental Table 5. Color indicates mutation type identified in a single patient; box indicates pathways enriched at relapse. Slice width represents the proportion of patients with mutation of at least 1 gene in indicated pathway. (D) Heatmap of significantly mutated genes and known driver genes across the cohort, with genes in rows and patients in columns. The 12 genes at top are those enriched specifically among relapse-specific variants (supplemental Methods), and genes in the bottom portion are frequently present at both diagnosis and relapse. At right, a bar plot of the percentage of patients mutated for each gene is shown, along with the pathway to which the gene belongs. Gray indicates that the mutation is shared at diagnosis and relapse (D+R), red indicates relapse-specific (R), and blue indicates diagnosis-specific (D). Subtypes and B- vs T-lineage are indicated at top. CDKN2A mutations occurred in 49% of samples, which is above the axis limit.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/135/1/10.1182_blood.2019002220/3/m_bloodbld2019002220f1.png?Expires=1769905088&Signature=xxSbYgzD~DOkSgGpQo1zMc7y-aKiy4nJwwrPEZZGV2bJzTGprAOZByllyFWvf4c8oQJtBzlm9mTSsnsrlrTZzG-OxpGC0dRNgSPBltxtMPqL8wipmff5YrmSNQysrrgqU0LFxUb~pI4nUzqTAvpN0c6le56BHzlEKCDr4NA2j-NM6p0-KpJXWSvN1OqODa0DS4YjPzqMI9FcgKHuUri4hEAz-DVzeQrXhoC-mLN-AJj~1rT7sdhlQlBvEUgLzgPPoTKs1VzLeBTTVi~2NnxEFiOiS~HlVHzziuKqu1LK~P3ukJWLY159U7PVcgxF8hYu4skB4AKKMYVlq7Au440iig__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)