Because of the rarity of nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL), there are limited data to guide therapy and no single approach to treatment has been agreed upon. In this issue of Blood, Binkley et al present a large, multicenter, retrospective series, which provides important insights on treatment patterns and outcomes in NLPHL.1

Their analysis includes 559 patients with early-stage NLPHL treated from 1995 through 2018 with either radiation therapy (RT) alone (46%), combined modality therapy (CMT) (32.9%), chemotherapy alone (8.4%), observation (6.6%), rituximab followed by RT (3.4%), or rituximab alone (2.7%). As expected with NLPHL, the outcomes for the patients were excellent, with a 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) of 87.1% and overall survival (OS) of 98.3%. Furthermore, prognosis was good regardless of treatment modality. Among the 2 most common therapies (RT and CMT), there was no significant difference in 5-year PFS (91.1% compared with 90.5%). Because of the inherent bias associated with retrospective analyses, we need to be cautious when comparing treatment modalities. In fact, there were slight differences in patient populations among the treatment modalities, with a higher proportion of favorable-risk patients (by German Hodgkin Study Group [GHSG] criteria) in the RT-only group. However, based upon the highly favorable survival rates in both the RT-only and CMT groups, these data suggest that RT alone may be sufficient for the majority of patients presenting with early-stage NLPHL.

Although it is traditionally treated like classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), NLPHL is characterized by a more favorable course; therefore, many have questioned whether it’s necessary to follow the same treatment paradigm used for cHL. This was demonstrated by an analysis from the GHSG that showed improved 50-month survival for patients with NLPHL vs cHL enrolled on prospective GHSG trials.2 On the basis of these observations, the authors concluded that perhaps NLPHL should be treated with less aggressive approaches. A recent update of their series included 251 patients with early-stage NLPHL followed for a median of 8.8 years.3 Patients were treated with stage-adapted therapy with RT, CMT, or chemotherapy, and the long-term outcomes were excellent, with 10-year PFS of 79.7% and OS of 93.3%. Importantly, as Binkley et al also noted in their article, only a minority of deaths were related to lymphoma, whereas most were related to second malignancies or nonmalignant conditions possibly related to therapy, thus providing further support for less intense therapy for NLPHL.

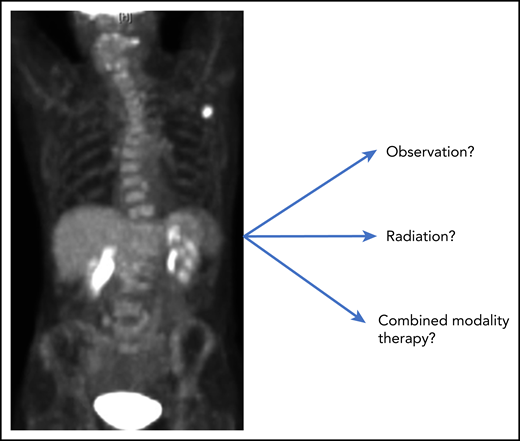

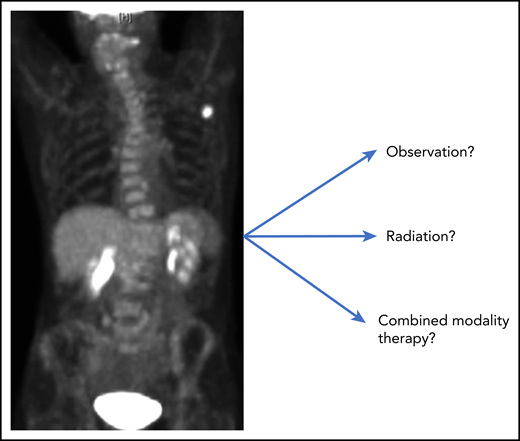

An additional important observation from the Binkley et al study was that risk of progression was ongoing as far out as 15 years after initial diagnosis. This raises the question of whether treating early-stage patients with RT changes the natural history of the disease and perhaps indicates that an initial course of observation may be appropriate (see figure). There are limited data regarding the role of active surveillance for early-stage NLPHL. Among 52 pediatric patients with stage IA disease who were observed after complete excision of the disease, a 5-year event-free survival of 77% was reported.4 In addition, similarly favorable outcomes resulted for the small number of patients in the Binkley et al study who were observed after excision. Borchmann and colleagues5 recently reported on a series of 37 patients from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center who were managed with active surveillance among which there were 23 patients with early-stage disease (without complete resection). The 5-year PFS for the early-stage patients initially managed with active surveillance was 65%; however, OS and time to progression after second-line therapy were identical in the surveillance and treatment groups, indicating that there is potentially no drawback from an initial course of observation.

As Binkley et al state in their discussion, “given the excellent survival for patients with early-stage NLPHL, any risk of late effects with a given treatment must be considered.” Thus, a less-is-more approach is warranted for patients with early-stage NLPHL, and prospective studies that evaluate active surveillance are needed. In the meantime, the data suggest that RT alone may be sufficient for most patients with early-stage NLPHL; however, to reduce the risk of any late effect of treatment, observation should be considered.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.J.M. has received research support from Seattle Genetics, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Incyte and honoraria from Miragen Therapeutics and Seattle Genetics.