Abstract

The field of malignant hematology has experienced extraordinary advancements with survival rates doubling for many disorders. As a result, many life-threatening conditions have since evolved into chronic medical ailments. Paralleling these advancements have been increasing rates of complex hematologic pain syndromes, present in up to 60% of patients with malignancy who are receiving active treatment and up to 33% of patients during survivorship. Opioids remain the practice cornerstone to managing malignancy-associated pain. Prevention and management of opioid-related complications have received significant national attention over the past decade, and emerging data suggest that patients with cancer are at equal if not higher risk of opioid-related complications when compared with patients without malignancy. Numerous tools and procedural practice guides are available to help facilitate safe prescribing. The recent development of cancer-specific resources directing algorithmic use of validated pain screening tools, prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug screens, opioid use disorder risk screening instruments, and controlled substance agreements have further strengthened the framework for safe prescribing. This article, which integrates federal and organizational guidelines with known risk factors for cancer patients, offers a case-based discussion for reviewing safe opioid prescribing practices in the hematology setting.

Introduction

In 2017, drug overdoses were the leading cause of injury-related deaths in the United States, exceeding cumulative US casualties from the Vietnam and Iraqj wars combined.1 With chronic use of opioids linked to significant risks, including life-threatening respiratory depression and opioid use disorder (OUD [addiction]), many states have passed legislation based on the 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, a comprehensive outline of tools and processes that are useful for safely prescribing opioids in populations without malignancies.2 These guidelines have proven particularly useful in painful benign hematologic conditions such as sickle cell disorder, parvovirus infection, thalassemia, and porphyria.

To date, the risks of opioid use in hematologic malignancies have not received much attention. However, improvements in diagnosis and treatment have necessitated more focused reflection on this topic. Within the United States, cancer-related death rates have been declining by almost 2% per year, and 5-year survival rates for all cancers are nearly 70%.3 In hematology, survival rates for multiple myeloma (52%), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (74%), and chronic myeloid leukemia (66%) have nearly doubled since the 1970s. The result has been the slow evolution of what were once imminently life-threatening conditions into resolved disease states or chronic medical ailments often accompanied by chronic pain. Today, a practicing hematologist can expect chronic pain to be referenced in at least 20% of patient encounters.4 In hematologic malignancies, ongoing pain is observed in 33% of patients during survivorship and 60% of patients who are actively receiving treatment.5 Up to 82% of patients with malignancy describe inadequate pain management (Table 1), and disease progression, invasive procedures, therapy-related neurotoxicity, psychological stressors, poorly coordinated pain treatment plans, and other confounders all contribute.6,7

The successes in cancer survivorship have left many hematologists in the difficult position of managing chronic opioid therapy. Studies show that 10% of opioid-naïve patients with cancer may continue to take opioids over the long term after undergoing curative intent surgery, and up to 33% continue to use them after curative-intent chemoradiation.8,9 Research also suggests that the combination of chronic opioid use with recurrent cancer treatment interventions and comorbid patient characteristics and/or psychological stressors increases long-term risk of chemical dependency to levels as high as if not higher than those of populations without malignancy.8,10-13 Such evidence must be counterbalanced with the knowledge that fear of addiction contributes to symptomatic undertreatment in an estimated 30% of patients with cancer.14 A 2018 survey found that 50% of palliative care patients were fearful of starting opioid therapy because of their misconceptions about risks of drug addiction, undesirable effects, and death.15 Extending beyond the fears about opioid addiction of patients, families, and caregivers, fears about prescribing opioids are increasingly prevalent among clinicians and lawmakers. A recent study by the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network and the Quality of Life Coalition found that 40% to 48% of former or current patients with cancer have had their clinicians indicate that treatment options for pain were limited by insurance coverage, laws, or guidelines.16

Balancing the risks and benefits of chronic opioid use for hematologic conditions remains a challenge. There are several paradoxical considerations at stake, so this article aims to provide an overview of how to safely prescribe opioids for those with hematologic malignancies through 3 case scenarios.

Case 1: considerations before initiating opioid therapy

A 54-year-old male with a history of essential thrombocythemia presents to discuss initiating opioids for his abdominal and diffuse bone pain which has persisted over the past year. With no previous history of thrombosis or bleeding events, he is considered to be at low risk for thrombosis and has a Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Assessment Form (MPN-SAF) score of 15, which suggests a mild disease burden with mild individual scores for abdominal pain and bone pain.17 He has received 6 months of therapy with interferon, and his platelet counts remain under 400/mL. He takes 81 mg of aspirin once per day and has historically avoided acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, fearing that they will increase the risk of bleeding. On abdominal examination, the spleen measures 10 cm below the left costal border, and he is diffusely tender to palpation throughout the abdomen. An abdominal computed tomography scan shows splenomegaly and no evidence of portal or mesenteric vein thrombosis. Examination of the extremities is unrevealing. How should this patient be educated on the nature of his pain and the risks, benefits, and expected outcomes of using opioids?

Comments

Pain is recognized as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.18 Understanding the origins of pain can help predict its natural history and help identify optimal treatments. Two well-recognized categories of pain19 are nociceptive pain, which develops from tissue injury or inflammation and initiates a nervous system response, and neuropathic pain, which results directly from nerve dysfunction or trauma. Chronic pain is defined as lasting >3 months or beyond the time expected for normal tissue healing.2 The pathophysiology driving chronic pain differs mechanistically from acute pain by increasing neuronal excitability, decreasing inhibition, and promoting maladaptive neuronal modifications.20 Screening for pain using a validated tool should be performed routinely throughout the course of treatment. All patients should be educated on the importance of setting realistic goals for symptom management and titrating pain regimens to achieve functionality as opposed to complete pain resolution.

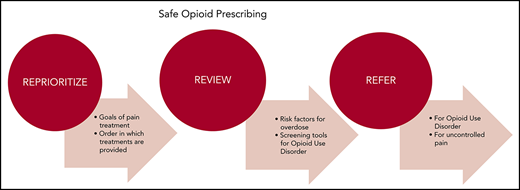

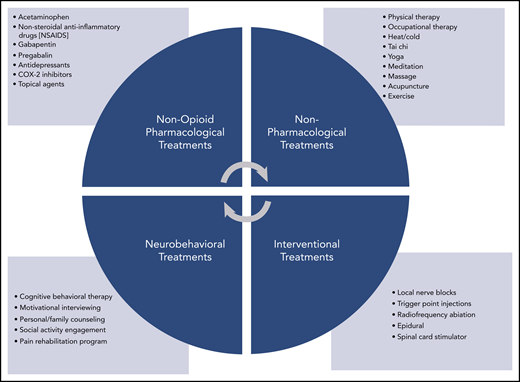

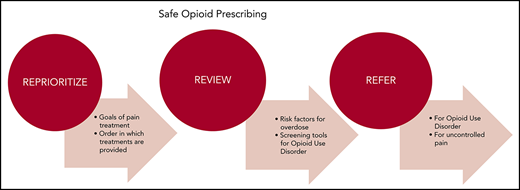

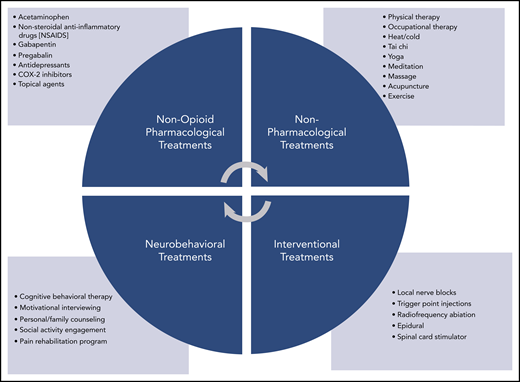

The World Health Organization’s cancer pain ladder offers a useful algorithm for determining the order in which pain treatments should be offered.21 As a dominant principal, non-opioid techniques should be tried before integrating opioids into the treatment plan (Figure 1).2,21 Pharmacologic treatments such as acetaminophen, ibuprofen, gabapentin, pregabalin, antidepressants, COX-2 inhibitors, and topical treatments as well as nonpharmacologic treatments such as physical or occupational therapy, tai chi, yoga, community social activities, and counseling are often used as first-line therapies. This approach is particularly applicable to nonmalignant pain and mild to moderate malignant pain. Exceptions may include patients with recent surgical interventions, severe pain, advanced malignancy, and end-of-life circumstances. If disease-specific therapy is likely to have a positive effect on alleviating symptoms, preference should be given to that approach. Many cases of malignancy-associated pain can be managed by hematologists without further referral. Clinicians specializing in complex pain treatment (palliative care and pain management specialists) should be engaged if adequate symptom control cannot be achieved within the hematology practice.

Pain treatment strategies. Potential non-opioid treatment strategies by category.

Pain treatment strategies. Potential non-opioid treatment strategies by category.

For moderate to severe cancer-related pain, opioids are promoted as first-line therapy and remain the most frequently used treatment strategy.22 Up to 75% of patients with advanced malignancy benefit from these agents, and their pain improves an average of 3 points on a pain rating scale of 0 to 10.23,24 Adequate pain control has been associated with increased patient satisfaction, improved patient engagement, adherence to therapeutic regimens, higher quality-of-life scores, reduced hospitalizations, and improved mood.25-27 However, use of opioids has significantly less evidence in the setting of chronic prescribing. Multiple randomized controlled trials suggest that chronic use of opioids offers minimal to modest pain relief with limited impact on patient functionality and high risk of toxicity.28-30 In addition to the more commonly recognized opioid complications (Table 2), worsening of baseline chronic pain (hyperalgesia), sleep disorders, lethargy, and reduced libido are all well documented.31,32 Dose-related increases in central nervous system depression, complications including fatal overdose (0.65% per year), and nonfatal overdose (up to 45% of patients) have been steadily increasing.33,34 Of concern, data show that prescription opioids account for up to 77% of opioid-related overdose fatalities.35 Opioids also have an impact on central dopamine and serotonin release, resulting in mood changes and stimulatory hedonic or reward benefits that readily propagate substance use disorder (0.1% to 34% of patients).33,34

Recent publications have also addressed a possible link between opioids and cancer progression. Opioids have been shown to suppress immune function via immunomodulation of transcription factors and receptors in lymphoid and myeloid cell lines.36,37 Opioids can also directly stimulate the mu opioid receptor, which results in activation of growth factor signaling pathways (including EGFR) in non–small-cell lung cancer and can lead to proliferation and migration via MAPK/ERK and Akt phosphorylation pathways.38-40 Similarly, murine models of breast cancer have shown mu opioid receptor immunoreactivity in larger tumors with morphine-promoted tumor angiogenesis, peri-tumoral lymphangiogenesis, increased cytokine release, mast cell activation, and substance-P release, all of which result in reduced overall survival.41 The evidence is still preliminary that suggests that opioids may facilitate promotion or progression of cancer, and its relevance to hematologic malignancies is unclear. At present, it is recommended that clinicians avoid using this information in clinical decision making. Nevertheless, it highlights our rudimentary understanding of the breadth of possible complications associated with these drugs.

Back to Case 1

The patient’s pain has been present for more than 3 months and is now deemed to be chronic. By using a validated symptom scoring tool, we find that his pain severity is mild. Although he has a malignancy, his mild pain suggests that he may benefit from a trial of non-opioid therapies. The patient should be educated on the chronic nature of his pain, and treatment goals need to be established as they relate to functionality. To begin with, we would recommend using acetaminophen on an as-needed basis in combination with physical therapy and/or yoga. Close follow-up should be scheduled to reassess functional status and the need for therapy adjustment.

Case 2: initiation and monitoring of patients receiving chronic opioid therapy

A 56 year-old-male with a history of multiple myeloma, asthma, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) presents to discuss pain management for uncontrolled chronic back pain. As a result of his myeloma, the patient has sustained numerous vertebral compression fractures. Previous treatments, including radiation, chemotherapy, and kyphoplasty, failed to offer significant pain relief. He successfully completed an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation 1 year ago and remains in complete clinical remission. Despite this, he continues to struggle with debilitating back pain that interferes with daily activities. His physical examination is unremarkable, and a recent magnetic resonance imaging scan of the spine shows no new pathology. He has tried using acetaminophen and ibuprofen with minimal relief, and for the past 6 months, he has used medical marijuana daily. He endorses trying leftover oxycodone prescriptions from previous hospitalizations and has found these to provide the greatest symptom relief. He would like to discuss using opioids on a regular basis.

Comments

Opioids represent the most common arsenal against refractory pain in both inpatient and outpatient settings. When less aggressive interventions have proven insufficient, the patient has severe malignancy-related pain, or is facing the end of life, it is often appropriate to initiate chronic opioid therapy. In general, chronic opioids are most effective when used in the right patient, for the right indication, at the right dose, and for the right length of treatment. However, applying that principle to an infinitely heterogeneous patient population leads to complex challenges. Therefore, it is recommended that the list of considerations offered in Table 3 be reviewed before prescribing chronic opioid use. Unquestionably, proper patient and drug selection are integral to balancing the benefits of enhanced analgesia with known toxicity profiles. The following steps should be considered before initiating chronic opioid therapy.

First, a patient risk assessment should be performed. Clinicians are encouraged to screen patients for their risk of developing OUD. Risk factors include current or previous substance abuse, age 18 to 45 years, poor socioeconomic status, concurrent psychiatric disorders (depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia), personal history of physical or sexual abuse, family history of substance abuse, chronic pain, and unwillingness to participate in multimodal treatment approaches.34,53-56 Several validated screening tools are available, including the Opioid Risk Tool (ORT),57 the Brief Risk Questionnaire (BRQ),58 and the Pain Medication Questionnaire (PMQ).59 It should be noted that prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) play an important role in identifying which controlled substance prescriptions the patient has recently filled and should be reviewed before opioids are prescribed. Because opioids are known respiratory depressants, all patients should be screened for risk of opioid overdose. Compromised cardiopulmonary function, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, active tobacco abuse, and reduced ejection fraction increase the risk of complications. Patients should also be screened for baseline liver and kidney functionality to ensure proper drug clearance.2,60 Concurrent use of opioids with benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, and other sedatives remains a major risk factor for overdose and contributes to up to 30% of opioid-related deaths.61

For patients identified as moderate risk or high risk for either OUD or overdose, a careful analysis of risks and benefits must be undertaken before prescribing. The review should take into consideration the patients current life expectancy, response to less aggressive interventions, and access to or adherence to adjunctive treatments. Importantly, prescribing patterns play a critical role in risk mitigation because therapy that lasts more than 30 days or doses above 120 morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) have high correlations with the development of OUD. A recent study identified that a 1-day opioid prescription is associated with a 6% risk of opioid use at 1 year.62 When the prescription duration is increased to 30 days, the risk of ongoing opioid use at 1 year is 30%. Opioids with high potency or rapid clearance across the blood-brain barrier result in greater dopamine surges and subsequent cravings. Thus, for milder pain refractory to non-opioid interventions, initial treatment with hydrocodone, codeine, tramadol, or low-dose morphine is preferred over fentanyl, hydromorphone, or oxycodone.

Second, patient and family education should be offered. All patients and families interested in initiating opioid therapy should be well educated on the multifaceted nature of pain and the risks and benefits of opioids.2 Clinicians are encouraged to document this discussion and to consider developing a standardized handout that includes the discussed content. This document may also double as a controlled substance agreement (CSA) if patient co-signature is included. The following topics should be addressed when constructing the handout: the importance of taking opioids only in the manner prescribed; the role of using opioids conjunctively with non-opioid therapies; the adverse effects of taking opioids; potential drug-drug interactions, including with alcohol, benzodiazepines, and drugs of abuse; warning signs of withdrawal; risks of addiction and overdose; safe opioid storage and disposal; and practice requirements for patient follow-ups, refills, CSA adherence, urine drug screens (UDSs), and pill counts.

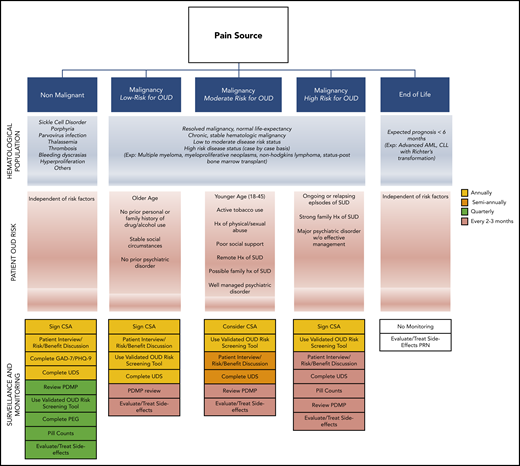

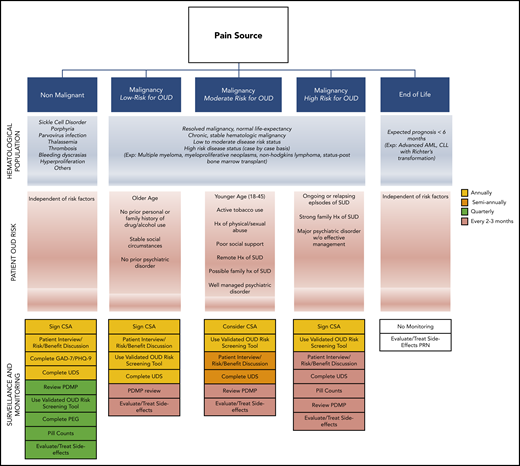

Close monitoring of patients receiving opioids on a chronic basis is essential.2,43,63,64 Elements included during routine monitoring are based on several factors, including state laws and the condition that opioids are being prescribed for. In general, the initial screening should evaluate the patient’s pain history and previous approaches to treatment, baseline characteristics, known risk factors for complications, and current functionality. Subsequent visits should focus on changes in risk factors, patient adherence, and response to therapy. Although practice protocols vary widely, Figure 2 offers a suggested monitoring algorithm based on patient condition.

Opioid monitoring algorithm. Suggested patient screening regimens for OUD during opioid prescribing based on patient condition and OUD risk. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Exp., example; Hx, history; SUD, substance use disorder.

Opioid monitoring algorithm. Suggested patient screening regimens for OUD during opioid prescribing based on patient condition and OUD risk. AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Exp., example; Hx, history; SUD, substance use disorder.

For patients with pain not related to their malignancy, we recommend adherence to the 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain.2 For patients with long life expectancies, we recommend following the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Practice Guidelines.43 For patients receiving end-of-life care, there are no formal monitoring guidelines, so management depends on the patient. Regardless of the patient’s condition, it is recommended that the PDMP be checked regularly to evaluate for drug-drug interactions and patient adherence. Clinicians may also wish to screen for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire 9 [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 [GAD-7]), and functionality (PEG [Pain, Enjoyment, General Activity] Pain Assessment).46-48 It is important to understand the benefits and limitations of standard urine drug screens. Initial screening tests are typically based on immunoassay and have low sensitivity with frequent false-positive results because they detect metabolites. In addition, their list of detectable opioids is often limited. A urine screen with reflex testing remains the preferred method for evaluation.65

Back to Case 2

The patient demonstrates several high-risk features for OUD and overdose, including a history of 2 psychiatric disorders and a primary pulmonary disease. His ongoing use of cannabis places him at further risk for opioid misuse and other mental health disorders.66 These risks must be balanced with fact that he has a known painful condition and that conservative treatments have failed, along with previous interventional approaches. The patient should be referred to a pain management specialist, and if he is not deemed a candidate for other pharmacologic or interventional treatments, a trial of opioid therapy could be considered. Before initiating opioids, it is important to have a discussion of risks and benefits, review his PDMP results, have him complete the GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PEG screens, perform a baseline urine drug screen, and jointly sign a CSA. Treatment should begin with low-dose, immediate-release oxycodone or morphine on a PRN (pro re nata [as needed]) basis with close outpatient monitoring performed quarterly. Each follow-up visit should involve a review of the PDMP and completion of the PEG tool to evaluate for functional improvements.

Case 3: management of opioid use disorders and other complications

A 33-year-old male with a history of chronic myelogenous leukemia complicated by thrombosis that resulted in a left below-the-knee amputation has just transferred into your practice. Outside records show that he has been well managed on dasatinib and remains in remission. Records also reveal that he was ultimately dismissed from his previous hematologist’s practice for behavioral issues, and he intermittently tested positive on UDSs for cocaine and heroin. During today’s visit, he informs you that he continues to have severe chronic phantom limb pain and abdominal pain, which he describes as being poorly managed by his previous hematologist with oxycodone PRN. Today, he asks for a higher dose of oxycodone and becomes hostile and demanding when you offer an alternative referral to pain management specialists and consideration of integrating non-opioid pain regimens. What are the next best steps to managing this patient?

Comments

Referenced interchangeably with addiction, OUD is viewed as a primary chronic disease of the brain resulting from dysfunction in reward, motivation, memory, and related brain circuitry.67 Development of the disorder involves a protracted process of CNS remodeling. With acute opioid use, patients may experience supraphysiological releases of dopamine which consequently result in upregulation of dopamine receptors. The result is corrupt messaging regarding stimulus-response, reward prediction, approach behavior, and learning patterns. Over time, users experience reduced availability of the dopamine receptors and require larger amounts of opioids to experience reward benefits. Patient behaviors slowly transition from initial controlled use motivated by positive reinforcement, to impulsive use, and ultimately compulsive use motivated by negative reinforcement. The final manifestation is pathological pursuit of reward or relief evidenced within biological, social, spiritual, and psychological domains. Early identification of patients who have developed OUD is essential because treatment may prevent death from overdose and other consequences.

Within the general population, between 21% and 29% of patients who have been prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, and up to 34% (average, 8%-12%) of patients without cancer develop OUD after use.33,34,68 Patients with cancer have historically been excluded from state, federal, and societal guidelines that govern opioid use. However, improvements in cancer survival and new studies demonstrating OUD in this population increase the possibility that these restrictions may someday be reconsidered. Ten percent of patients with cancer and no previous use of opioids before curative surgery continued to take the drug for the subsequent 3 to 6 months after surgery.9 Notably, OUD rates in that population seem to be similar to if not higher than those in patients without cancer histories because of co-existing risk factors. In 1 study, 8.9% of patients with cancer had at least 1 risk factor for OUD, and 1 of every 25 patients with cancer demonstrated behaviors strongly suggestive of substance use disorder, including illicit drug use, double doctoring, drug diversion, or significant ethanol use.69 Another study found that 17% of palliative patients screened positive on the CAGE (cut-annoyed-guilty-eye opener) questionnaire for alcohol use disorder, a risk factor for polysubstance use disorder.70 In a retrospective medical records review of 232 oncology patients, clinicians ordered a UDS based on their clinical judgment of a patient’s risk of substance misuse.11 Results showed that 40% of patients ultimately were screened with a UDS, and in 46% of cases, results were positive for non-prescribed opioids, benzodiazepines, or illicit substances. In addition, 39% of patients tested had inappropriately negative UDSs raising concern for nonadherance, diversion, or hoarding.

In another retrospective study of palliative patients who completed the ORT, 43% were identified as medium to high risk for OUD, and abnormal UDS results were found in 45% of patients.10 Specifically, within hematology patients, our myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN) Quality of Life subgroup completed an online survey of 416 MPN patients. The MPN patients currently receiving opioids (17%) were compared with MPN patients not receiving opioids (83%). The study identified that those receiving opioids had significant risk factors for OUD and overdose, including a personal history of substance use or abuse (20.2%), high rates of baseline respiratory illness (33.0%), mental health disorders (60.1%), and moderate-risk to high-risk ORT scores (24.6%). Similar to patients without cancer, up to 8.8% of MPN patients scored mild to moderate for OUD by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), and palliative care and pain management were involved in only 34.3% of cases.

Chemical coping, or the use of opioids to avoid dealing with the psychological distress of cancer, overlaps with OUD and is present in up to 18% of patients with cancer.12 It can be challenging to differentiate OUD from misuse as a result of uncontrolled pain, chemical coping, and patient misunderstanding of instructions. Behaviors such as increasing the frequency of opioid dosing without authorization from the clinician, seeking pain medications from multiple clinicians, obtaining opioids from family members, and emphatic requests for opioid prescriptions may frequently be misinterpreted as drug-seeking behaviors when in fact they actually represent undertreated pain. Features more suggestive of OUD include cravings or a strong desire to use opioids, unwillingness to cut down usage, continued use despite physical or psychological problems associated with opioid use, and spending unusual amounts of time or atypical means to obtain opioids. Importantly, tolerance and withdrawal are expected features of chronic opioid use and are not considered characteristic of OUD in patients taking opioids for legitimate reasons. Ultimately the diagnosis of OUD is made via DSM-5.45 Because many clinicians feel uncomfortable using DSM-5, early referral for additional screening is strongly recommended. Screening may be performed with greater expertise by those in a variety of subspecialty fields such as addiction medicine clinicians, addiction psychiatrists, clinicians with buprenorphine certification, and by substance abuse treatment programs.

Standard-of-care treatment of OUD includes initiation of opioid replacement therapy in the form of agonist (buprenorphine, methadone) or antagonist (naltrexone) treatments in conjunction with neurobehavioral therapies. More than 90% of patients with OUD who discontinued opioids without opioid replacement therapy return to using opioids within 1 year, independent of whether opioids were tapered or abruptly discontinued. Patients may subsequently seek these opioids from illicit sources, which reinforces the importance of avoiding abrupt discontinuation.71 Clinicians are encouraged to have conversations with patients who have OUD, even if they are challenging, that include discussing and documenting evidence that supports the condition, reinforcing OUD as a medical disorder, and encouraging immediate assessment. Opioid tapering is reasonable in patients who have OUD behaviors and who refuse referral assessments. All patients at risk for overdose (ie, those who have OUD, high-risk cardiopulmonary conditions, daily doses of >50 MME) should be offered a prescription for naloxone. Many clinicians prefer intranasal naloxone because it is easy to administer, and several states now allow this drug to be provided as an over-the-counter drug.

Back to Case 3

This patient demonstrates a number of concerning features for OUD, including ongoing reports of pain despite resolution of acute injury, evidence of polysubstance abuse, hostile behavior, and unwillingness to seek alternative treatments. Practice policies regarding documentation and referrals should be used and should include reviewing his PDMP results, discussing concerns for OUD with him, making referrals to OUD treatment specialists, and offering him a prescription for naloxone. To avoid withdrawal symptoms and the risk that he may seek opioids from illicit sources, it may be appropriate to provide a short course of oxycodone for him (or preferably buprenorphine if the clinician carries a DEA-X number [Drug Enforcement Administration number for physicians granted a waiver to prescribe certain types of drugs such as buprenorphine]) as a bridge to his OUD assessment appointment. Concurrent referral to palliative care should also be considered.

Conclusions

Safe opioid prescribing in the hematology practice can involve complicated decisions that require a thorough understanding of pain and opioid-related risks and benefits. Baseline patient characteristics play a critical role in determining candidacy for opioid therapy, and clinicians are encouraged to use national and organizational guidelines to assess and monitor patients during treatment. The future of medicine will likely offer us advanced alternatives to opioids with improved safety profiles and greater impact on chronic pain syndromes. As we await these medical developments, clinicians are encouraged to base their prescribing patterns on available guidelines and adjust practice techniques as knowledge evolves.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robyn Scherber and Craig Reeder for their careful review of this manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: H.L.G., H.G., and R.M. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Holly L. Geyer, Mayo Clinic, 5777 E Mayo Blvd, Phoenix, AZ 85054; e-mail: geyer.holly@mayo.edu