Key Points

Human ETS1 deficiency inhibits expression of several NK cell–linked key transcription factors and inhibits NK cell differentiation.

ETS1 is required for tumor cell–induced NK cell cytotoxicity and interferon-γ production.

Abstract

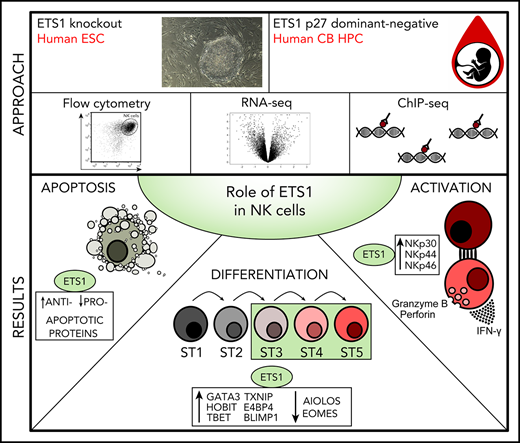

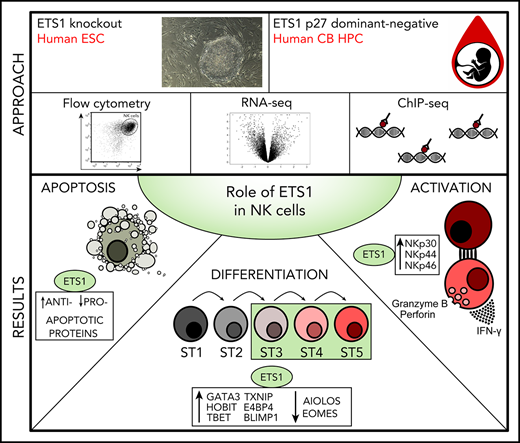

Natural killer (NK) cells are important in the immune defense against tumor cells and pathogens, and they regulate other immune cells by cytokine secretion. Although murine NK cell biology has been extensively studied, knowledge about transcriptional circuitries controlling human NK cell development and maturation is limited. By generating ETS1-deficient human embryonic stem cells and by expressing the dominant-negative ETS1 p27 isoform in cord blood hematopoietic progenitor cells, we show that the transcription factor ETS1 is critically required for human NK cell differentiation. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis determined by RNA-sequencing combined with chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing analysis reveals that human ETS1 directly induces expression of key transcription factors that control NK cell differentiation (ie, E4BP4, TXNIP, TBET, GATA3, HOBIT, BLIMP1). In addition, ETS1 regulates expression of genes involved in apoptosis and NK cell activation. Our study provides important molecular insights into the role of ETS1 as an important regulator of human NK cell development and terminal differentiation.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells play a crucial role in the defense against viral infections and carcinogenesis through lysis of infected or transformed cells. Via secretion of cytokines, they also regulate T and B cells.1 In patients with acute myeloid leukemia, transplanted donor NK cells expressing mismatched inhibitory receptors provide a graft-versus-leukemia effect in the absence of graft-versus-host disease.2 There are several ongoing studies and clinical trials for NK cell immunotherapy as treatment for leukemia and solid cancers.3

Differentiation and lineage specification of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) into myeloid and lymphoid cells is regulated by transcription factors. NK cells are derived from common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs). NK cell progenitors (NKPs) express CD122, become interleukin-15 (IL-15) responsive, and are NK cell restricted. During further differentiation, inhibitory and activating NK cell receptors are expressed, and functional capabilities, such as cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion, are eventually acquired. In contrast to mouse, detailed knowledge of the regulation of human NK cell differentiation is lacking. Due to increased interest in NK cells as therapeutic agents, a more complete understanding of the molecular basis of human NK cell differentiation is desirable. However, because there are important differences between mouse and human NK differentiation, human models remain essential for translational purposes.

The transcription factor ETS1 is predominantly expressed in lymphoid cells. Ets1−/− mice have reduced NK cell numbers that display lower cytolytic activity.4,5 The role of ETS1 in human NK cell biology remains unknown. There are 3 human ETS1 isoforms: ETS1 p51, encoded by exons I to VII; ETS1 p42, lacking the sequences encoded in exon VII; and ETS1 p27, lacking the sequences encoded in exons III to VI.6-8 ETS1 p42 acts as a gain-of-function protein because the autoinhibitory motif that suppresses DNA binding is absent. ETS1 p27 possesses the DNA-binding domain flanked by inhibitory domains but lacks the Pointed and the transactivation domains, which are required for the transactivation of ETS1 target genes. It has been shown that ETS1 p27 binds DNA in the same way as ETS1 p51, but it has a dual-acting dominant-negative effect because it not only acts at the transcriptional level by blocking ETS1 p51–mediated transactivation of target genes but also affects the subcellular localization by inducing the translocation of ETS1 p51 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm.

Here, we reveal the role of ETS1 in human NK cell differentiation and terminal differentiation by performing knockout, loss-of-function, and overexpression experiments. NK cell differentiation is inhibited as a consequence of absent or reduced ETS1 function. Transcriptome and chromatin immunoprecipitation–sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis reveals that ETS1 directly induces expression of 6 key transcription factors that have been previously reported to control NK cell differentiation and/or maturation. Finally, residual NK cells in ETS1 loss-of-function display defective cytotoxicity and cytokine production on tumor cell contact, presumably due to reduced expression of activating NK cell receptors. Our data provide molecular insights into the role of ETS1 as a critical regulator of human NK cell biology.

Methods

ETS1-deficient human embryonic stem cells and hematopoietic differentiation

WA01 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) were kept in an undifferentiated state using the hESC medium (KOSR)/MEF platform/WiCell Feeder Dependent Protocol (https://www.wicell.org/). Single-cell–adapted hESCs were generated as described9 and used to generate ETS1−/− hESCs via CRISPR/Cas9 technology10,11 targeting exon A/1. Detailed information is presented in the supplemental Methods (available on the Blood Web site).

Umbilical cord blood HPC differentiation

CD34+ HPCs were in vitro differentiated into NK cells as described by Cichocki and Miller,12 with modifications (supplemental Methods).

Viral constructs

Complementary DNA encoding human ETS1 p51 or ETS1 p27 was subcloned from the pLEXhETS1p51HAtag (kindly provided by L.A. Garrett-Sinha, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY) and pCDNA3hETS1p27 vector8 into the LZRS–internal ribosome entry site–enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) retroviral vector.13 The empty LZRS–internal ribosome entry site–eGFP vector was used as control. Virus was generated as described.

Flow cytometry

Cultures were evaluated by using an LSRII flow cytometer, and data were analyzed with the FACSDiva Version 6.1.2 (both from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and/or FlowJo_V10 software (Ashland, OR). The antibodies used are listed in the supplemental Methods.

Functional assays

Interferon-γ assays

For intracellular interferon-γ (IFN-γ) flow cytometric detection, cells from day 21 (d21) cocultures were stimulated with K562 cells at a 1:1 ratio for 6 hours or with IL-12/IL-18 (both 10 ng/mL) or IL-12/IL-15 (4 ng/mL)/IL-18 for 24 hours. Brefeldin A (BD GolgiPlug; BD Biosciences) was added during the last 4 hours. NK cell surface marker staining was performed; cells were then fixed and permeabilized (Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit; BD Biosciences) and stained for IFN-γ.

For detection of secreted IFN-γ, eGFP+CD45+CD11a+CD56+CD94+ NK cells were sorted from d21 cultures using an FACSAria III cell sorter (BD Biosciences) and stimulated with IL-12/IL-18 or IL-12/IL-15/IL-18 for 24 hours. Secreted IFN-γ was quantified by using the human IFN-γ enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay PeliKine-Tool set (Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

CD107a detection assay

Cells from d18 to d21 cocultures were stimulated by coculture with K562 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) during 2 hours, as described by Bryceson et al.14

51Chromium release assay

K562 target cells were labeled with Na251CrO4 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). eGFP+CD45+CD11a+CD94+ NK cells were sorted from d18 to d21 cocultures and added at various ratios to 51chromium-labeled K562 cells. After 4 hours, supernatant was harvested and measured in a 1450 LSC&Luminescence Counter (Wallac MicroBeta TriLux; PerkinElmer). The mean percentage of specific lysis of triplicate wells was calculated.

Library preparation, sequencing, quantitative polymerase chain reaction, and identification of putative ETS1-binding sites

Viable d18 eGFP+CD45+CD11a+CD56+CD94+ NK cells were sorted to perform transcriptome analysis. Samples were sequenced with high-throughput NextSeq 500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) flow cell–generating 75 bp single reads. Differential expression analysis was performed by using DESeq2. Details can be found in the supplemental Methods.

For ChIP-seq, sorted viable peripheral blood NK cells were crosslinked in 1% formaldehyde. Protein-DNA complexes were immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal anti-ETS1 antibody (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Immune complexes were isolated with protein A agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Crosslinks were reversed at 65°C. After DNA purification, Illumina sequencing libraries were prepared from the ChIP and input DNAs by the standard consecutive enzymatic steps of end-polishing, dA-addition, and adaptor ligation. After a final polymerase chain reaction amplification step, the resulting DNA libraries were quantified and sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 system. The supplemental Methods provide detailed information. Putative ETS1-binding sites in promotors and enhancers were detected by analysis using MACS2 and HOMER software.15,16

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS version 24 software (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). A P value generated by a Student t test <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

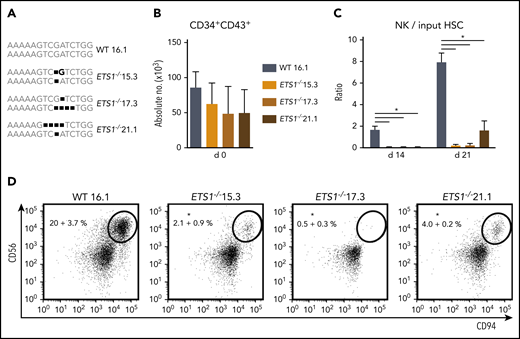

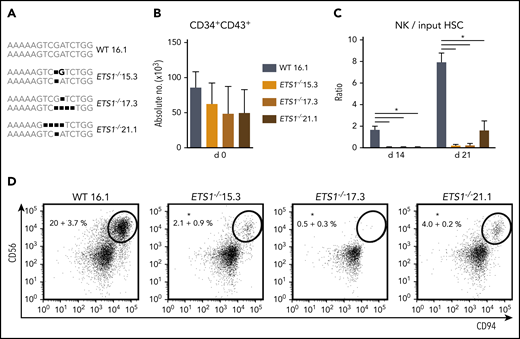

Strongly reduced capacity of ETS1 knockout hESCs to differentiate into NK cells

An ETS1-specific guide RNA was selected that efficiently generated ETS1 knockout clones by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology in Jurkat cells (supplemental Figure 1). Using the same guide RNA in hESCs, we selected 3 hESC ETS1−/− clones (15.3, 17.3, and 21.1) that carried nucleotide deletions resulting in a biallelic frameshift. The wild-type clone (16.1) underwent similar selection processes (Figure 1A). hESC clones were differentiated into HPCs (CD34+CD43+). Homozygous ETS1 deficiency had no significant effect on absolute HPC numbers (Figure 1B). hESC-derived HPCs were cultured in NK differentiation conditions. Wild-type hESCs efficiently generated NK cells, confirming earlier studies17 ; however, significantly fewer NK cells were generated from each ETS1−/− clone (Figure 1C-D). Thus, although ETS1 is not required for differentiation of hESCs into HPCs, it is crucial for NK cell development thereof.

ETS1 deletion in human embryonic stem cells severely impairs NK cell development. (A) Three homozygous ETS1 knockout (ETS1−/−) hESC clones were generated by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology to introduce mutations in exon A/1 by non-homologous end joining. The wild-type (WT) clone underwent the same selection processes. The sequence of the targeted region of exon A/1 is indicated for both alleles, showing biallelic frameshifts in the knockout clones. (B) WT and mutated hESCs were differentiated into hematopoietic CD34+CD43+ progenitor cells. Cell numbers are indicated (mean ± SEM; n = 4-6). (C-D) CD34+CD43+ cells were subsequently cultured in NK cell–differentiating conditions. (C) The ratio of the cell numbers of generated NK cells (gated as CD45+CD56+CD94+) over the input precursor stem cell number was determined (mean ± SEM; n = 4-6) on d14 and d21. (D) Representative dot plots of d21 cultures are shown, with the indicated NK cell percentage in the CD45+ gated population. Significant difference compared with the WT clone, *P < .05 (Student t test).

ETS1 deletion in human embryonic stem cells severely impairs NK cell development. (A) Three homozygous ETS1 knockout (ETS1−/−) hESC clones were generated by using CRISPR/Cas9 technology to introduce mutations in exon A/1 by non-homologous end joining. The wild-type (WT) clone underwent the same selection processes. The sequence of the targeted region of exon A/1 is indicated for both alleles, showing biallelic frameshifts in the knockout clones. (B) WT and mutated hESCs were differentiated into hematopoietic CD34+CD43+ progenitor cells. Cell numbers are indicated (mean ± SEM; n = 4-6). (C-D) CD34+CD43+ cells were subsequently cultured in NK cell–differentiating conditions. (C) The ratio of the cell numbers of generated NK cells (gated as CD45+CD56+CD94+) over the input precursor stem cell number was determined (mean ± SEM; n = 4-6) on d14 and d21. (D) Representative dot plots of d21 cultures are shown, with the indicated NK cell percentage in the CD45+ gated population. Significant difference compared with the WT clone, *P < .05 (Student t test).

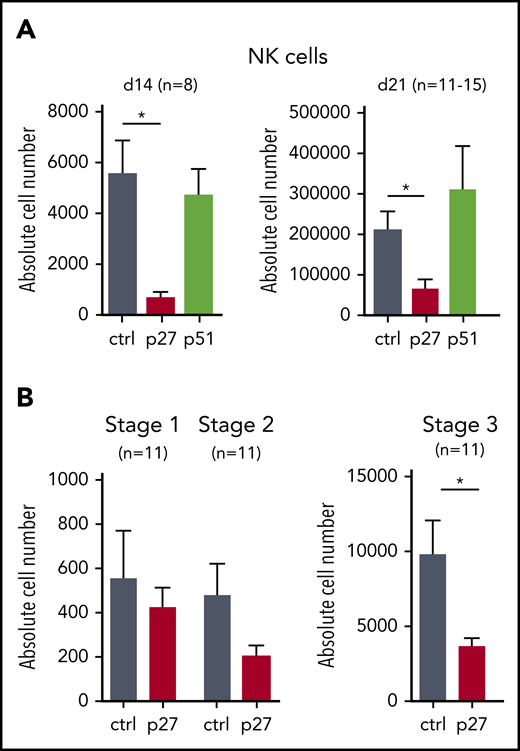

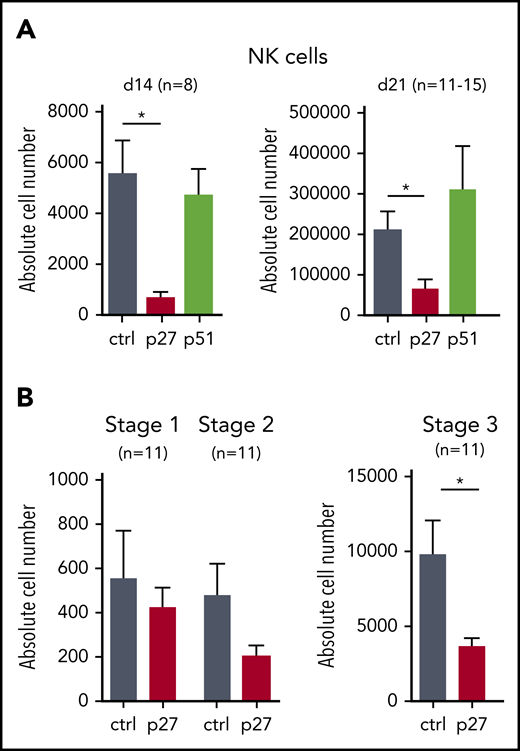

ETS1 expression is essential for human NK cell differentiation from cord blood HPCs

HPCs generated from hESCs resemble yolk sac hematopoietic progenitors with limited stem cell activity.18 We therefore also studied the role of ETS1 in NK differentiation from cord blood (CB) HPCs, which are considered bona fide HPCs. We transduced dominant-negative ETS1 p27 and full-length ETS1 p51 into CB HPCs, next to a vector control, and stable overexpression was observed (supplemental Figure 2A-D). ETS1 p27 transduction resulted in strong reduction of NK cell numbers (gated as shown in supplemental Figure 3A), whereas ETS1 p51 overexpression had no effect (Figure 2A). Because we observed less mature NK cells in ETS1 loss-of-function conditions, we investigated whether ETS1 affects earlier NK developmental stages. Although stage 1 cells (CD34+CD45RA+CD117–) (gating shown in supplemental Figure 3B) were not affected, stage 2 cells (CD34+CD45RA+CD117+) displayed a trend in lower cell numbers in ETS1 p27 cultures, which became significant in stage 3 cells (CD34–CD117+CD94–NKp44–) (Figure 2B). These results show that ETS1 is an essential factor in human NK cell generation from CB HPCs starting at stage 3.

ETS1 loss-of-function in CB HPC inhibits NK cell differentiation. (A) Upon transduction with control (ctrl), ETS1 p27, or ETS1 p51 vectors, sorted CB CD34+Lin–eGFP+ precursor cells were cultured in NK cell–differentiating conditions. Absolute cell numbers of NK cells were determined at the indicated time points. (B) Absolute cell numbers of differentiation stage 1 to stage 3 were determined at d14. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the number of experiments is indicated. Significant difference compared with ctrl, *P < .05 (Student t test).

ETS1 loss-of-function in CB HPC inhibits NK cell differentiation. (A) Upon transduction with control (ctrl), ETS1 p27, or ETS1 p51 vectors, sorted CB CD34+Lin–eGFP+ precursor cells were cultured in NK cell–differentiating conditions. Absolute cell numbers of NK cells were determined at the indicated time points. (B) Absolute cell numbers of differentiation stage 1 to stage 3 were determined at d14. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the number of experiments is indicated. Significant difference compared with ctrl, *P < .05 (Student t test).

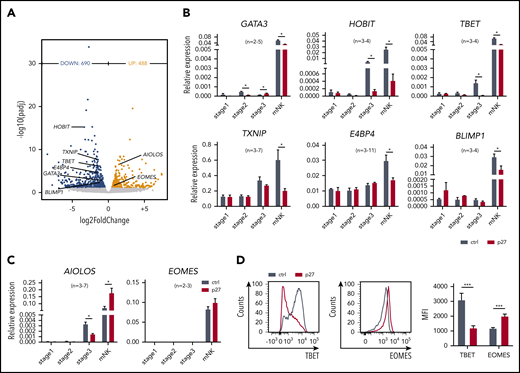

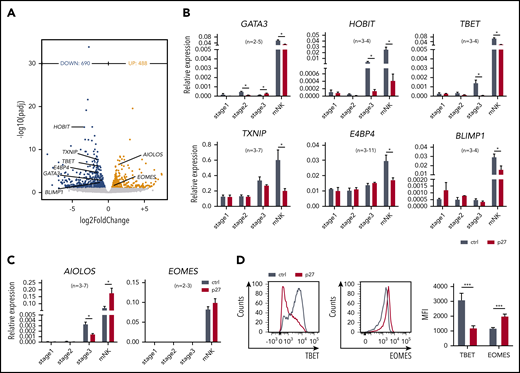

ETS1 regulates expression of key transcription factors linked to NK cell differentiation

To achieve mechanistic insight, the genome-wide transcriptome of sorted ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells was determined by RNA-sequencing. A total of 1178 differentially expressed genes were identified (Figure 3A). ETS1 p27 NK cells displayed downregulated expression of molecules related to lymphocyte differentiation (supplemental Figure 4). Strikingly, several key transcription factors of murine and/or human NK cell differentiation were repressed; that is, GATA3, HOBIT (ZNF683), TBET (TBX21), TXNIP, E4BP4 (NFIL3), and BLIMP1 (PRDM1). Inversely, AIOLOS (IKZF3) and EOMES (EOMESODERMIN) were upregulated. This was confirmed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and/or flow cytometry (Figure 3B-D).

ETS1 directly regulates expression of several key transcription factors linked to NK cell differentiation. (A) NK cells were sorted from d18 control and ETS1 p27 cultures, and RNA-sequencing was performed. Volcano plot showing downregulated (blue) and upregulated (red) genes in NK cells from ETS1 p27 vs control (n = 4). Differentially expressed NK cell–related transcription factors are indicated. (B-C) NK cell–linked transcription factors that were differentially expressed as shown in panel A were evaluated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis in all stages. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the number of experiments is indicated. (D) Representative dot plots of flow cytometry analysis of TBET and EOMES expression in mature NK cells. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SEM (n = 8) is shown. Significant difference compared with control, *P < .05 and ***P < .001 (Student t test). mNK, mature NK cells.

ETS1 directly regulates expression of several key transcription factors linked to NK cell differentiation. (A) NK cells were sorted from d18 control and ETS1 p27 cultures, and RNA-sequencing was performed. Volcano plot showing downregulated (blue) and upregulated (red) genes in NK cells from ETS1 p27 vs control (n = 4). Differentially expressed NK cell–related transcription factors are indicated. (B-C) NK cell–linked transcription factors that were differentially expressed as shown in panel A were evaluated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis in all stages. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the number of experiments is indicated. (D) Representative dot plots of flow cytometry analysis of TBET and EOMES expression in mature NK cells. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SEM (n = 8) is shown. Significant difference compared with control, *P < .05 and ***P < .001 (Student t test). mNK, mature NK cells.

Expression of these 8 transcription factors was also tested in the precursor stages. None was differentially expressed at stage 1. In ETS1 p27 stage 2 cells, GATA3 expression was significantly reduced, whereas it was increased at stage 3. At stage 3, HOBIT, TBET, and AIOLOS expression was reduced in ETS1 p27 cultures (Figure 3B-C).

Thus, ETS1 p27 first affects GATA3 (from stage 2), then HOBIT, TBET, and AIOLOS (from stage 3); at the mature NK cell stage, the expression of all 8 transcription factors is compromised.

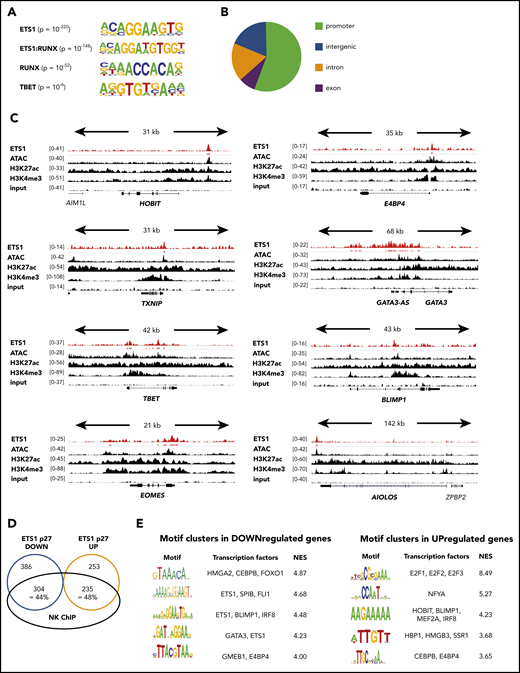

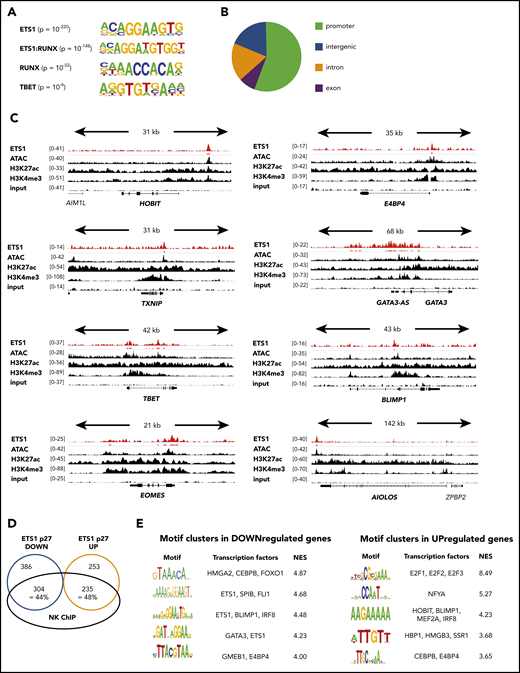

Multiple key NK cell–linked transcription factors are direct ETS1 targets

Although ETS1 ChIP data are available for human non-NK immune subpopulations and cell lines, they were not available for murine or human NK cells. Because it is well known that target genes of transcription factors are cell type specific, we performed ETS1 ChIP-seq on unmanipulated human NK cells and detected 7738 ETS1 peaks. The primary motif identified was ETS1, validating the ChIP-seq experiment, followed by ETS1:RUNX and RUNX motifs (Figure 4A). This is in line with previous findings that ETS1 and RUNX1 bind in a cooperative manner to large cohorts of enhancers controlling T lineage commitment.19 The TBET motif was also enriched, albeit with lower significance. This outcome suggests that these transcription factors share regulatory regions. The ETS1-binding motif was mainly found within promoter regions (Figure 4B), whereas RUNX and TBET motifs were enriched in enhancers (data not shown). This indicates that differential complex formation provides a mechanism by which ETS1 can be directed to other genomic locations.

ETS1 ChIP analysis of human ex vivo peripheral NK cells. (A-D) ETS1 ChIP-seq analysis was performed on sorted human peripheral blood NK cells. (A) Known motifs were identified with the HOMER package, and the 4 most significant motifs are shown. (B) Locations of ETS1 ChIP peaks relative to genomic annotations. (C) Genome browser tracks of NK cell–linked transcription factor genes are shown for human NK cell ETS1 ChIP-seq vs input DNA, vs H3K4me3 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq and ATAC-sequencing. (D) Identification of the proportion of genes that are potentially directly regulated by ETS1. (E) Nonbiased analysis of enriched transcription factor motifs in the downregulated and upregulated genes of ETS1 p27 NK cells by using the computational method iRegulon.

ETS1 ChIP analysis of human ex vivo peripheral NK cells. (A-D) ETS1 ChIP-seq analysis was performed on sorted human peripheral blood NK cells. (A) Known motifs were identified with the HOMER package, and the 4 most significant motifs are shown. (B) Locations of ETS1 ChIP peaks relative to genomic annotations. (C) Genome browser tracks of NK cell–linked transcription factor genes are shown for human NK cell ETS1 ChIP-seq vs input DNA, vs H3K4me3 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq and ATAC-sequencing. (D) Identification of the proportion of genes that are potentially directly regulated by ETS1. (E) Nonbiased analysis of enriched transcription factor motifs in the downregulated and upregulated genes of ETS1 p27 NK cells by using the computational method iRegulon.

Importantly, combined analysis of the ETS1 ChIP-seq data with available ATAC-sequencing, as well as H3K4me3 and H3K27ac ChIP-seq data from human NK cells,20 revealed that ETS1 ChIP peaks were present in promotors or enhancers of the aforementioned ETS1-regulated NK cell–linked key transcription factors (Figure 4C; supplemental Table 1).

There was a 44% and 48% overlap between ETS1 ChIP-seq peaks and ETS1 p27 downregulated and upregulated genes, respectively (Figure 4D). Nonbiased analysis of enriched transcription factor motifs21 in ETS1 p27 downregulated and upregulated genes shows that motifs for BLIMP1, E4BP4, GATA3, and HOBIT were significantly enriched (Figure 4E).

Thus, several transcription factors identified by others to be important in NK cell biology are differentially expressed in ETS1 loss-of-function conditions, and ChIP data indicate that these are direct ETS1 targets. In addition, whereas part of the differentially expressed genes overlap with the ETS1 ChIP peaks, motifs of several of the differentially expressed NK cell–linked transcription factors are also enriched in downregulated and upregulated genes of the ETS1 p27 cultures.

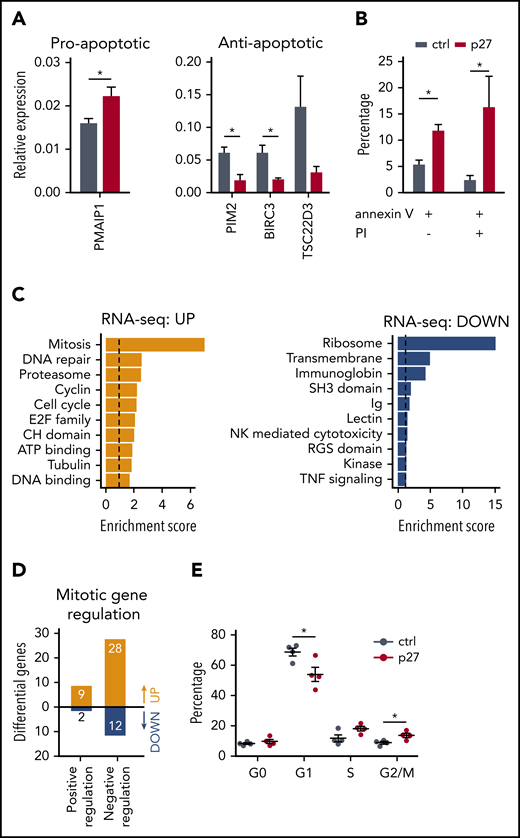

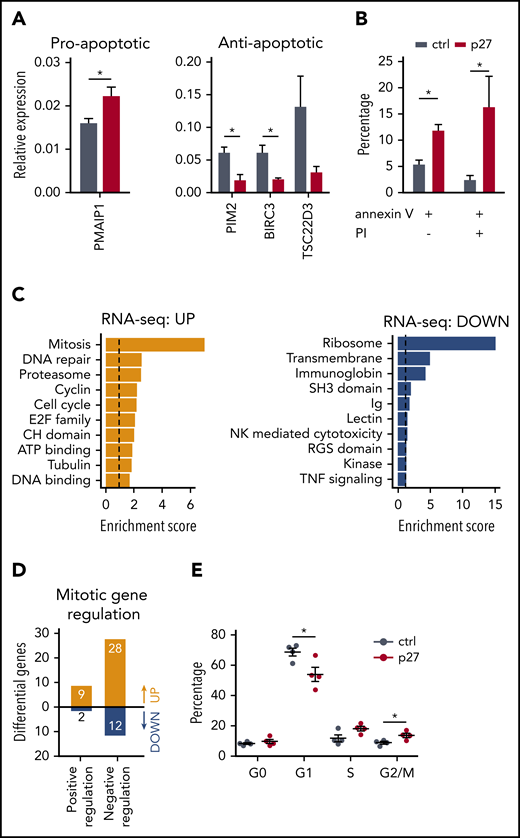

Increased apoptosis in NK cells from ETS1 p27 cultures

We investigated whether the lower NK cell number in the ETS1 p27 cultures (Figure 2) resulted from increased apoptosis and/or decreased proliferation. The programmed cell death pathway was enriched in the upregulated genes of ETS1 p27 NK cells (supplemental Figure 5). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction confirmed higher expression of the proapoptotic gene PMAIP-1 and lower expression of several antiapoptotic genes, including TSC22D3, BIRC3, and PIM2, in ETS1 p27 cultures (Figure 5A). This corresponded to increased apoptosis in ETS1 p27 NK cells (Figure 5B). In addition, ChIP-seq analysis revealed that antiapoptotic genes are direct ETS1 targets (supplemental Table 1).

ETS1 p27 expression increases apoptosis in NK cells. (A) NK cells were sorted from d14 control and ETS1 p27 cultures. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction results are shown for the relative expression of indicated proapoptotic and antiapoptotic genes (mean ± SEM; n = 3-7). (B) NK cells from control and ETS1 p27 cultures were analyzed at d14 for apoptosis using annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining. The percentage annexin V and/or PI-positive cells in the NK cell gate is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3-4). (C) Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes of the RNA-sequencing analysis of ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells. The 10 most significant pathways are shown. (D) The number of upregulated and downregulated genes of ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells in the Gene Ontology positive and negative regulation of the mitotic cell cycle pathways. (E) Cell cycle analysis of d18 NK cells by 7-AAD/Ki67 staining. The percentage of cells at the indicated cell cycle phases is shown (n = 4). Significant difference compared with control, *P < .05 (Student t test). ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ctrl, control.

ETS1 p27 expression increases apoptosis in NK cells. (A) NK cells were sorted from d14 control and ETS1 p27 cultures. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction results are shown for the relative expression of indicated proapoptotic and antiapoptotic genes (mean ± SEM; n = 3-7). (B) NK cells from control and ETS1 p27 cultures were analyzed at d14 for apoptosis using annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining. The percentage annexin V and/or PI-positive cells in the NK cell gate is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 3-4). (C) Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes of the RNA-sequencing analysis of ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells. The 10 most significant pathways are shown. (D) The number of upregulated and downregulated genes of ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells in the Gene Ontology positive and negative regulation of the mitotic cell cycle pathways. (E) Cell cycle analysis of d18 NK cells by 7-AAD/Ki67 staining. The percentage of cells at the indicated cell cycle phases is shown (n = 4). Significant difference compared with control, *P < .05 (Student t test). ATP, adenosine triphosphate; ctrl, control.

The mitosis pathway was enriched in ETS1 p27 upregulated genes (Figure 5C), suggesting that proliferation would be increased. However, further analysis showed that the majority of these upregulated genes negatively regulate mitosis (Figure 5D; supplemental Table 2). Cell cycle analysis showed that the percentage of nonproliferating (G0) cells was not different in ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells. In proliferating cells, there was a small significant decrease in G1 cells and an increase at the G2/M phase (Figure 5E). We observed similar proliferation rates in cell trace experiments starting at d14 of culture and analyzed after 7 days (data not shown).

Thus, increased apoptosis results in reduced NK cell numbers in ETS1 p27 cultures.

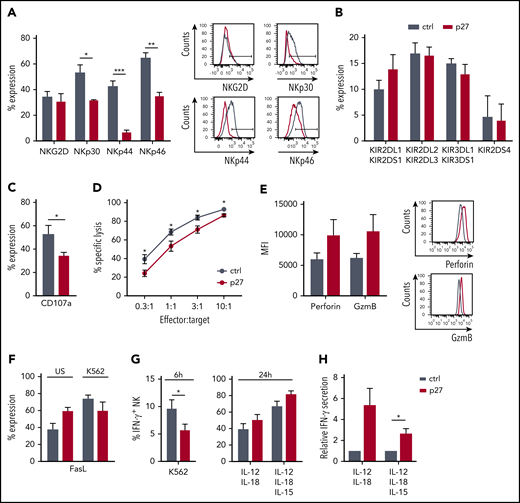

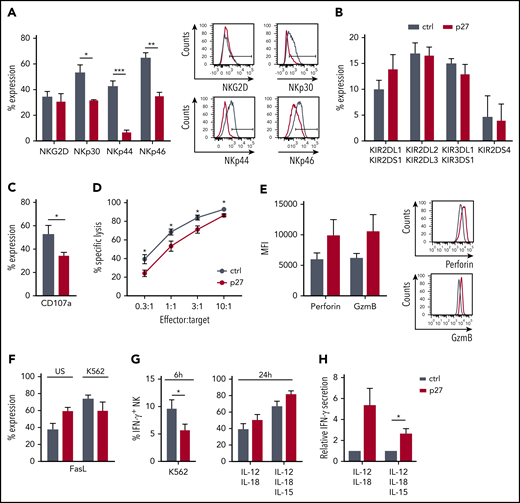

ETS1 is required for NK cell cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production upon tumor cell recognition

NK-mediated cytotoxicity is one of the significant pathways of downregulated genes in ETS1 p27 NK cells (Figure 5C). Because activating receptors trigger NK cell cytotoxicity, we first analyzed NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 expression. Whereas NKG2D expression was unaffected, NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 expression was decreased in ETS1 p27 NK cells (Figure 6A). KIR receptor expression did not differ from that of control NK cells (Figure 6B). Functionally, ETS1 p27 NK cells displayed less effective degranulation upon K562 coculture (Figure 6C), as well as reduced killing (Figure 6D). However, perforin and granzyme B protein levels tended to be higher (Figure 6E). The lower cytotoxicity of ETS1 p27 NK cells is not due to other killing pathways, as Fas ligand expression was not different in control vs ETS1 p27 cultures; this was true for unstimulated and K562 target-stimulated NK cells (Figure 6F). TRAIL expression was undetectable (data not shown).

ETS1 influences NK cell terminal differentiation and function. (A-B) Flow cytometric expression of the indicated receptors on gated NK cells from d21 control (ctrl) and ETS1 p27 cultures (mean ± SEM; n = 5-15). (C) d18 to d21 NK cells were stimulated with an equal number of K562 target cells, and CD107a expression was determined (mean ± SEM; n = 8). (D) The cytotoxic capacity of sorted d18 to d21 NK cells against K562 targets was determined in a 51chromium release assay. Data are expressed as the percent specific lysis as a function of the effector:target ratio (mean ± SEM; n = 6). (E) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of perforin and granzyme B (GzmB) expression in ctrl and ETS1 p27 NK cells (n = 6). (F) Fas ligand expression of NK cells that were unstimulated (US) or stimulated for 2 hours with K562 cells (n = 5). (G) Cells from d21 ctrl and ETS1 p27 cultures were stimulated with K562 cells for 6 hours, or with IL-12/IL-18 or IL-12/IL-15/IL-18 for 24 hours, and IFN-γ production was determined by flow cytometry in gated NK cells (mean ± SEM; n = 4-12). (H) Sorted d21 NK cells were stimulated with IL-12/IL-18 or IL-12/IL-15/IL-18 for 24 hours, and secreted IFN-γ was measured by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The relative IFN-γ production compared with ctrl is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 6-7). Significant difference compared with ctrl, *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 (Student t test).

ETS1 influences NK cell terminal differentiation and function. (A-B) Flow cytometric expression of the indicated receptors on gated NK cells from d21 control (ctrl) and ETS1 p27 cultures (mean ± SEM; n = 5-15). (C) d18 to d21 NK cells were stimulated with an equal number of K562 target cells, and CD107a expression was determined (mean ± SEM; n = 8). (D) The cytotoxic capacity of sorted d18 to d21 NK cells against K562 targets was determined in a 51chromium release assay. Data are expressed as the percent specific lysis as a function of the effector:target ratio (mean ± SEM; n = 6). (E) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of perforin and granzyme B (GzmB) expression in ctrl and ETS1 p27 NK cells (n = 6). (F) Fas ligand expression of NK cells that were unstimulated (US) or stimulated for 2 hours with K562 cells (n = 5). (G) Cells from d21 ctrl and ETS1 p27 cultures were stimulated with K562 cells for 6 hours, or with IL-12/IL-18 or IL-12/IL-15/IL-18 for 24 hours, and IFN-γ production was determined by flow cytometry in gated NK cells (mean ± SEM; n = 4-12). (H) Sorted d21 NK cells were stimulated with IL-12/IL-18 or IL-12/IL-15/IL-18 for 24 hours, and secreted IFN-γ was measured by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The relative IFN-γ production compared with ctrl is shown (mean ± SEM; n = 6-7). Significant difference compared with ctrl, *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 (Student t test).

To analyze the role of ETS1 in IFN-γ production, cells were stimulated with K562 target cells. This process resulted in lower IFN-γ production in ETS1 p27 NK cells compared with the control (Figure 6G). Upon stimulation with IL-12/IL-18 or IL-12/IL-15/IL-18, no significant trend occurred in increased IFN-γ production by ETS1 p27 NK cells, as evidenced by intracellular IFN-γ analysis, and IFN-γ secretion was significantly higher upon IL-12/IL-15/IL-18 stimulation as measured by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Figure 6H).

Thus, ETS1 loss-of-function inhibits expression of several activating NK cell receptors and reduces granule-mediated cytotoxicity and tumor target–induced IFN-γ production. Cytokine-induced IFN-γ production is not affected.

To study whether ETS1 is required to maintain NK cell functionality, mature NK cells were analyzed upon transduction with control vs ETS1 p27 retrovirus. Degranulation and cytotoxicity, as well as IFN-γ production and secretion, were not affected (supplemental Figure 6). This scenario indicates that ETS1 mainly exerts its effects during NK cell differentiation and is not essential to maintain the functionality of mature NK cells.

Discussion

Insight into the regulatory role of transcription factors in human NK biology is still in its infancy. We found that ETS1 regulates expression of several key transcription factors known to act at different levels of NK cell development, including E4BP4, TBET, TXNIP, GATA3, BLIMP1, HOBIT, AIOLOS, and EOMES. These are direct ETS1 targets as determined by using ChIP-seq analysis. We therefore show that ETS1 is an important regulator of human NK cell development and terminal differentiation.

Endogenous ETS1 expression is detectable at stages 1 and 2 of human NK cell differentiation and rises at stage 3 to reach levels equivalent to mature NK cells.22 This scenario is consistent with our findings, which showed that ETS1 deficiency in hESCs does not influence the generation of HPCs; also, ETS1 p27 in CB HPCs does not affect development of stages 1 and 2, whereas stage 3 and mature NK cells are significantly decreased. These results are similar to what has been observed in Ets1−/− mice, in which CLPs are not affected and pre-NKP and refined NK precursor (rNKP) are decreased.5

We found that human ETS1 orchestrates expression of transcription factors that play key roles in NK cell biology. Murine E4bp4 controls NK cell commitment. E4bp4−/− mice display reduced development of CLPs into NK progenitors, having less immature NK cells (NK1.1+DX5–), and mature NK cells (NK1.1+DX5+) are almost absent.23-25 The requirement for E4bp4 in NK cell differentiation is restricted to NKPs, as ablation of E4bp4 in NK cells does not affect NK cell numbers.26 Txnip is a stress–response gene expressed from NK progenitors. NK progenitors, as well as mature NK cell numbers, are reduced in Txnip−/− mice, correlating with decreased CD122 expression.27 Eomes−/− mice have reduced transition from early CD27+CD11b– into intermediate CD27+CD11b+ NK cell stages, whereas T-bet−/− mice have reduced NK cell numbers in the final CD27-CD11b+ stage.28,29 Mice deficient for both T-bet and Eomes have a complete loss of NK cells in all organs.29 T-bet and Eomes thus have both redundant and specific activities.28-34 Murine Ets1 induces T-bet expression,5 whereas Eomes expression depends on E4bp4.24 It is thus remarkable that human EOMES expression is upregulated in response to ETS1 loss-of-function that, in contrast to observations in the mouse, results in E4BP4 downregulation. However, limited numbers of murine Eomes-positive tissue-resident NK cells are still able to develop in the absence of E4bp4, which suggests alternate molecular mechanisms for the induction of Eomes expression.35-37 Also, Eomes and T-bet levels correlate inversely in differentiating murine NK cells, suggesting that negative feedback mechanisms regulate their balance,30,38 which possibly explains enhanced EOMES and decreased TBET expression in human ETS1 p27 NK cells. Murine Gata3−/− NK cells display reduced CD27+CD11b– to CD27+CD11b+ transition and decreased NK cell numbers in peripheral organs.39,40 Gata3 deletion ablates generation of murine IL-7Rα+ thymic NK cells.41 Conventional murine Gata3−/− NK cells have decreased T-bet expression.40

One of the most affected transcription factors in human ETS1 p27 NK cells is HOBIT. In mice, Hobit is highly expressed in liver tissue–resident NK cells, whereas it is virtually absent in liver and spleen conventional NK cells. In line with this, only murine liver tissue–resident NK cells are Hobit dependent.42 In contrast to murine findings, HOBIT is the most upregulated transcription factor during NK cell differentiation from CB HPCs, and HOBIT knockdown results in reduction of NK progenitors and largely abrogates NK cell generation. The remaining NK cells exhibit unaltered degranulation, whereas IFN-γ production is increased.43 Blimp1, a homolog of Hobit, is required for terminal maturation of murine spleen NK cells. Residual NK cells have an unaltered capacity of IFN-γ production and cytotoxicity in vitro, although RMA-S tumor growth in vivo is increased.44 Although most NK-linked transcription factors were repressed in ETS1 p27 NK cells, expression of AIOLOS (IKZF3) and EOMES was significantly increased. Murine Aiolos is constitutively expressed in the NK cell lineage, and Ikzf3−/− mice have a block in terminal differentiation.45 This differentiation block resembles that found in mice lacking T-bet and Blimp1; however, mice lacking either T‐bet, Blimp1, or both proteins have normal Aiolos expression, suggesting that Aiolos functions at a different level in NK cell differentiation.45

Taken together, we have shown a remarkable influence of ETS1 on expression of several transcription factors that have key roles in NK cell development, as shown before by the generation of knockout mice for these individual factors. Whereas the dominant-negative ETS1 p27 isoform significantly reduces expression of each of these 6 key transcription factors in human models, it does not completely abolish expression. The severely compromised human NK cell differentiation in the absence of functional ETS1 is therefore presumably due to the synergistic effect of reduction of expression of these different key NK cell–linked transcription factors. NK cells in Ets1−/− mice also have decreased Tbet expression but, in contrast to ETS1 p27 NK cells, have decreased Eomes and increased E4bp4 and Helios expression. Also in contrast to findings in Ets1−/− mice,5 we detected no difference in the other IKAROS family member, HELIOS (IKZF2), in ETS1 p27 NK cells.

It can be argued that the dominant-negative ETS1 isoform also affects binding and transcriptional regulation by other ETS family proteins, as members of the ETS family are characterized by a well-conserved DNA-binding domain. Approximately one-half of the ETS members are significantly expressed in mature NK cells (supplemental Table 3). However, in this context, it is important that the full-length ETS1 (p51) is autoinhibited for its binding to DNA due to the presence of 2 inhibitory domains surrounding and interacting with its DNA-binding domain.46 To counteract autoinhibition and improve DNA binding, ETS1 interacts with partners, enabling their cooperative binding to adjacent DNA elements.47 This binding autoinhibition brings an additional degree of complexity and specificity in the transcriptional function of ETS1 p51 and enhances the specificity of ETS1 function compared with other ETS proteins that are not autoinhibited. This compelling need for partners is essential for ETS1 function and results in a particular space-time function. Both inhibitory domains surrounding the DNA-binding domain are conserved in ETS1 p27, suggesting that ETS1 p27, as with the full-length ETS1 p51 isoform, is autoinhibited for DNA binding. In this way, Ets-1 p27 may not be a dominant-negative protein for other members of the ETS family.

To study the underlying cause of the lower NK cell number in ETS1 p27 cultures, we tested both apoptosis as well as proliferation. Apoptosis was significantly increased and correlated with decreased expression of antiapoptotic genes that were also direct ETS1 targets as shown by ChIP-seq, including TSC22D3, BIRC3, and PIM2, as well as with increased expression of proapoptotic genes such as PMAIP1. Both proapoptotic and antiapoptotic features have been ascribed to ETS1, depending on the biological context.48-51 Increased apoptosis also accounts for the markedly decreased murine mature thymocyte and peripheral T-cell numbers generated from Ets1−/− precursors.52,53 Transcriptome analysis showed that although the mitosis pathway was enriched in ETS1 p27 upregulated genes, the majority of these genes negatively modulate mitosis. Cell cycle analysis further showed that there was no major difference in ETS1 p27 vs control NK cells. Overall, this indicates that the lower ETS1 p27 NK cell number is due to increased apoptosis rather than to a difference in proliferation.

ETS1 has an important role in human NK cell terminal differentiation and function as ETS1 p27 NK cells exhibit reduced cytotoxicity and target cell–induced IFN-γ production. The activating receptors NKG2D, NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 are important to activate both NK cell cytotoxicity and cytokine production upon tumor target recognition.54,55 Although NKG2D expression was unaffected, expression of NKp30, NKp44, and NKp46 was decreased in ETS1 p27 NK cells. In addition, NK cells in Ets1−/− mice have unaffected expression of NKG2D and decreased expression of NKp46.5 Human ETS1 ChIP peaks were present in promotors or enhancers of NCR1, NCR2, and NCR3, which encode NKp46, NKp44, and NKp30, respectively (supplemental Table 1). This suggests that ETS1 directly regulates expression of these activating NK cell receptors. In addition, the reduced ETS1 p27 NK cell functionality can be enforced by the altered expression of several transcription factors proven to be involved in functional maturation of NK cells (ie, Aiolos, E4BP4, TXNIP, GATA3, T-bet). Murine Aiolos−/− NK cells display a hyperreactive response toward tumor cells in vivo, suggesting a negative regulatory role of Aiolos in NK cell activation.45 The enhanced AIOLOS expression in human ETS1 p27 NK cells might therefore contribute to decreased cytotoxicity. Murine E4bp4−/− and Txnip−/− NK cells show impaired cytotoxicity, and Gata3 and Txnip are required for efficient IFN-γ production.23,27,39 Also, T-bet has been described as essential for functional maturation of murine NK cells.28 Although TBET was repressed in ETS1 p27 NK cells, the decreased cytotoxicity of murine T-bet−/− NK cells has been attributed to the decreased production of perforin and granzyme B,29 whereas both perforin and granzyme B were increased in human ETS1 p27 NK cells. Similarly, NK cells from Ets1−/− mice contain higher amounts of perforin and granzyme B.5

The current study provides mechanistic insight into the role of ETS1 in human NK cell biology by showing that ETS1 loss-of-function results in altered expression of 8 key transcription factors that have been linked to NK cell development and terminal differentiation in mouse and/or human. In addition, ETS1 loss-of-function leads to altered gene expression linked to increased apoptosis and decreased expression of activating NK cell receptors. Finally, cytotoxicity and IFN-γ production are decreased upon tumor cell contact.

The crucial role of ETS1 in development and function of not only B or T cells but also of NK cells suggests that genetic aberrations within the gene give rise to immune-related diseases. Genome-wide association studies have identified single nucleotide polymorphisms in or near the ETS1 gene or in ETS1-specific binding motifs of target genes. Accordingly, ETS1 is regarded as a locus of susceptibility for a wide range of autoimmune and inflammatory disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, ulcerative colitis, type 1 diabetes, and allergy.20,56 However, the causal relationship between ETS1 and these disorders is still a subject of future research.

Contact the corresponding author for original data.

Data are accessible on the Gene Expression Omnibus repository (accession number GSE124104; token: adkxagywplqxhkp).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Imke Velghe for help with hESC maintenance and culture.

This work was supported by grants from the Research Foundation-Flanders (grants G.0444.17N, 12N4515N, 1S45317N, 1S29317N, and 1831317N; G.L., S.T., S.W., L.K., and T.C.C.K., respectively) and Kinderkankerfonds (a nonprofit childhood cancer foundation under Belgian law; P.V.V. and W.V.L.). The computational resources (Stevin Supercomputer Infrastructure) and services used in this work were provided by the VSC (Flemish Supercomputer Center), funded by Ghent University, Research Foundation-Flanders, and the Flemish Government–department EWI.

Authorship

Contribution: S.T., S.W., and G.L. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; S.T., S.W., L.K., E.P., E.V.A., and K.D.M. performed research; W.V.L., J.R., and L.T. performed the bioinformatics analysis; M.A., P.M., F.V.N., T.C.C.K., P.V.V., T.T., and B.V. contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools; and S.T. and S.W. collected data and performed statistical analysis.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for S.T. is Orionis Biosciences, Ghent, Belgium.

The current affiliation for K.D.M. is AZ Sint-Lucas, Ghent, Belgium.

Correspondence: Georges Leclercq, C. Heymanslaan 10, MRB2 entrance 38, 9000 Ghent, Belgium; e-mail: georges.leclercq@ugent.be.

REFERENCES

Author notes

S.T. and S.W. contributed equally to this study.