In this issue of Blood, Fuchs et al1 have used T-cell biology, coupled with Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and computational leverage of public databases, to open new horizons in the landscape of minor histocompatibility antigens (MiHAs) in hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT).

Lethal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can occur after allogeneic HCT even when patient and donor are siblings completely matched for both parental human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes.2 The enigma behind this apparent contradiction was solved in the 1990s by seminal work from Els Goulmy’s group at the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), who identified MiHAs (ie, peptides with polymorphic amino acids mismatched between patient and donor) as the targets of alloreactive T cells mediating GVHD after HLA-matched HCT3 and characterized the first MiHA at the molecular level.4 Unlike classical HLA molecules, MiHAs do not form readily detectable serological epitopes, precluding their antibody-based discovery. Instead, identification of these peptide antigens required sophisticated T-cell cloning coupled with immunopeptidomics, which at that time was still at its beginnings. The technical hurdles associated with the identification of MiHAs limited their comprehensive characterization for years to come, and very few new MiHAs were identified within the decade that followed their initial discovery. Important progress was made following in the footsteps of the early work at the LUMC by van Bergen and colleagues,5 who leveraged GWAS for higher throughput identification of MiHAs, eventually resulting in the characterization of 78 MiHAs.6

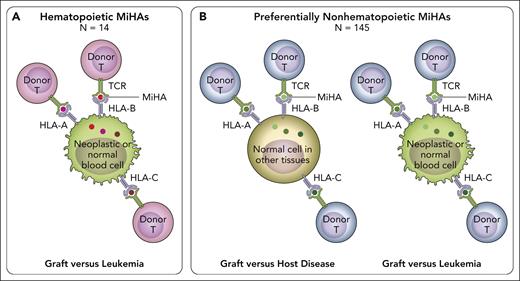

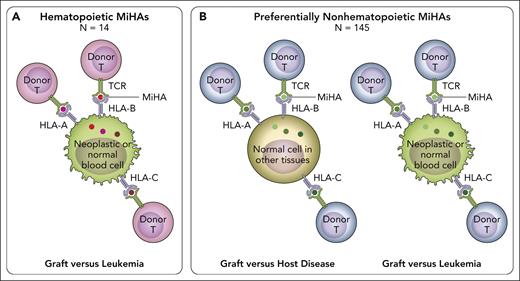

The platform for MiHA discovery has now been elevated to a new level by Fuchs et al, who coupled GWAS-based identification of MiHAs with computational mining of public databases for tissue-specific expression patterns of the genes encoding the underlying polymorphic variants. This is of crucial clinical importance, because of the well-known dichotomy between toxic GVHD and the beneficial graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect (ie, immune control of the underlying hematologic malignancy), which is a hallmark of allogeneic HCT.7 After HLA-identical HCT, both GVL and GVHD are mediated by alloreactive donor T cells recognizing mismatched MiHAs on neoplastic hematopoietic cells and GVHD target organs, respectively. Therefore, reducing the risk of relapse comes at the price of increasing GVHD.8 The holy grail in allogeneic HCT is to identify strategies for separating GVL from GVHD. One approach to reach this ambitious goal is the identification of hematopoietic MiHAs (ie, MiHAs expressed on hematopoietic cells and their neoplastic derivatives but not on nonhematopoietic tissues including GVHD target organs; see figure). T-cell alloreactivity against hematopoietic MiHAs leads to selective GVL. In contrast, recognition of preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs (ie, MiHAs broadly expressed on hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissues) will induce both GVL and GVHD. Until now, only 3 hematopoietic MiHAs were known.6 The elegant study by Fuchs et al has more than tripled this number for a total of 14 such MiHAs. These could be exploited not only for peptide vaccination approaches, but also for novel targeted therapies using immune cells equipped with the relevant T-cell receptors, which can easily be identified from the corresponding T-cell clones.

In HLA-matched HCT, alloreactive donor T cells recognize patient-specific MiHA peptides presented by HLA-A, -B, or -C molecules, via their T-cell receptor (TCR). (A) Hematopoietic MiHAs (red dots) are expressed selectively on hematopoietic tissues including their neoplastic derivatives (green cells), but not or to a much lesser extent on GVHD target tissues. Recognition of patient-specific hematopoietic MiHAs by alloreactive donor T cells after transplantation can lead to GVL (ie, control of the malignant disease) without GVHD (ie, T-cell-mediated damage to healthy tissues). Donor T-cell recognition of patient-specific hematopoietic MiHAs will not be harmful to the donor’s blood system reconstituted after successful HCT, because it carries the donor-specific variant of the relevant MiHA. The work by Fuchs et al added 11 new hematopoietic MiHAs to the 11 previously known ones, for a total number of 14. These hematopoietic MiHAs hold promise for new strategies of targeted leukemia immunotherapy. (B) Preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs (green dots) are broadly expressed on different tissues including GVHD target organs (light brown cells), in addition to varying levels of expression in hematopoietic tissues and their malignant derivatives (green cells). Recognition of patient-specific preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs by alloreactive donor T cells after transplantation can lead to both toxic GVHD and beneficial GVL. The study by Fuchs et al added 70 new preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs to the 75 previously known ones, for a total number of 145. Together, the 14 hematopoietic and 145 preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs cover most of the MiHA repertoire presented by several common HLA allotypes and provide an invaluable benchmark for the assessment of MiHAs as biomarkers for HCT outcome. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

In HLA-matched HCT, alloreactive donor T cells recognize patient-specific MiHA peptides presented by HLA-A, -B, or -C molecules, via their T-cell receptor (TCR). (A) Hematopoietic MiHAs (red dots) are expressed selectively on hematopoietic tissues including their neoplastic derivatives (green cells), but not or to a much lesser extent on GVHD target tissues. Recognition of patient-specific hematopoietic MiHAs by alloreactive donor T cells after transplantation can lead to GVL (ie, control of the malignant disease) without GVHD (ie, T-cell-mediated damage to healthy tissues). Donor T-cell recognition of patient-specific hematopoietic MiHAs will not be harmful to the donor’s blood system reconstituted after successful HCT, because it carries the donor-specific variant of the relevant MiHA. The work by Fuchs et al added 11 new hematopoietic MiHAs to the 11 previously known ones, for a total number of 14. These hematopoietic MiHAs hold promise for new strategies of targeted leukemia immunotherapy. (B) Preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs (green dots) are broadly expressed on different tissues including GVHD target organs (light brown cells), in addition to varying levels of expression in hematopoietic tissues and their malignant derivatives (green cells). Recognition of patient-specific preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs by alloreactive donor T cells after transplantation can lead to both toxic GVHD and beneficial GVL. The study by Fuchs et al added 70 new preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs to the 75 previously known ones, for a total number of 145. Together, the 14 hematopoietic and 145 preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs cover most of the MiHA repertoire presented by several common HLA allotypes and provide an invaluable benchmark for the assessment of MiHAs as biomarkers for HCT outcome. Professional illustration by Patrick Lane, ScEYEnce Studios.

In addition to these hidden treasures of potentially actionable targets in histocompatibility, Fuchs et al also identified 70 new preferentially nonhematopoietic MiHAs, thereby more than doubling the total number of known MiHAs to a total of 159. The new MiHAs are presented by 7 common HLA class I allotypes with population frequencies >20%. Importantly, the authors show that increasing the number of patients under study did not increase the number of new MiHAs restricted by these common HLA allotypes, suggesting that the dominant repertoire of these frequent MiHAs has been mostly identified. Overall, 137 of 159 (86.1%) of the known MiHAs were mismatched in at least 1 of the 39 patients from this study, but only 108 of 137 (78.8%) of the mismatched MiHAs were actually targeted by T cells in at least 1 patient. From the data presented, it can be extrapolated that each patient carried an average number of mismatched or targeted MiHA of 14.7 (6-24) and 4.6 (1-12), respectively, suggesting that not all mismatched MiHAs are equally immunogenic. Immunogenicity was pinpointed to HLA-B7 and HLA-A2 as restriction elements for 78 of 159 (49%) of the known MiHAs, with an enrichment for polymorphic arginine for MiHAs presented by HLA-B7. Whether these observations can be leveraged for the prediction of immunogenicity in other antigen sources remains to be investigated. Importantly, T cells for 45 of 108 (41.7%) targeted MiHAs were found in more than 1 of the 39 patients, showing that almost half of the MiHA repertoire is recurrent. Moreover, 37 of 159 (23.3%) of the known MiHAs were of cryptic origin (ie, derived from noncanonical open reading frames). This percentage substantially exceeds previous estimates based on reverse proteogenomics, highlighting the potential relevance of the cryptic peptide repertoire as a source of antigens for cancer immunotherapy. Together, these findings further emphasize the role of the HLA immunopeptidome, which has recently been identified as an important driver of alloimmune responses in HLA-mismatched HCT,9,10 as a target of clinically relevant T-cell alloreactivity also in the matched setting. The tempting hypothesis that presentation of immunogenic MiHAs across different but structurally related HLA class I allotypes might contribute to their immunogenicity in HLA-mismatched HCT awaits further investigation.

The study from Fuchs et al represents a milestone that maps much of the territory which surrounded the murky molecular nature of MiHAs presented by common HLA class I allotypes since their discovery. This finally opens the door to investigations likely to provide much needed answers regarding their relevance as biomarkers in HCT, by patient-donor MiHA genotyping and HLA-peptide multimer tracking of MiHA-specific T cells in informative patients. Even more importantly, the findings highlight hematopoietic MiHAs, including those derived from the cryptic peptide repertoire, as potentially actionable targets in histocompatibility, for the design of new strategies to preventing or treating post-HCT relapse. Exploring the repertoire also of HLA class II–restricted MiHAs, which predictably are of no lesser importance than the HLA class I–restricted ones, will be one of the future challenges to lift additional hidden treasures of histocompatibility for the improvement of patient outcomes.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interest.