In this issue of Blood, Locke et al describe the safety and efficacy outcomes of axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) across racial and ethnic groups.1 Their study included 1,290 patients in the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research registry who received standard-care axi-cel between 2017 and 2020 for large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) as well as 106 and 169 axi-cel recipients who received axi-cel in the ZUMA-1 and ZUMA-7 clinical trials, respectively.

Although safety and efficacy outcomes were largely consistent among different races and ethnicities, the most striking findings were the efficacy outcomes in non-Hispanic Black (NHB) patients. When comparing NHB patients with non-Hispanic White (NHW) patients, a lower overall response rate (odds ratio 0.37), complete response rate (odds ratio 0.57), and progression-free survival (hazard ratio 1.41) were observed. The cumulative incidence of relapse was higher for NHB patients. Overall survival was comparable among all racial/ethnic groups. These findings are consistent with other similar reports on LBCL.2

In addition, NHB patients were younger (median age 55.5 years) than Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian (NHA), and NHW patients (median age 58.3, 61.8, and 63 years, respectively). Disease characteristics, such as elevated lactate dehydrogenase, histologic transformation, or chemosensitivity, were comparable between groups. However, a higher percentage of NHB patients (75%) received axi-cel ≥12 months from diagnosis to infusion compared with other race/ethnicity groups. NHB patients were less likely to have been eligible for ZUMA-1 criteria based on lines of therapy and were more likely than other groups to have a longer “vein-to-vein” time of ≥28 days.

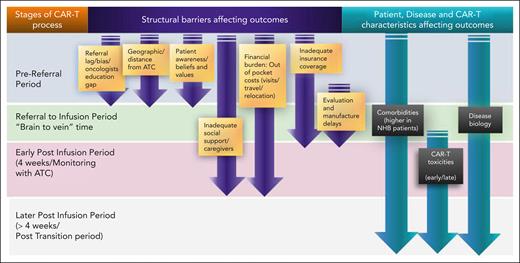

These findings not only raise awareness but also give further insight into the possible underlying factors at play, including elements of patient and disease characteristics, and perhaps the greater element of inequitable access to care. These factors can affect several inflection points during the chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy process (see figure).

Access and outcome factors across stages of the CAR-T therapy process. ATC, authorized treatment center.

Access and outcome factors across stages of the CAR-T therapy process. ATC, authorized treatment center.

First, the differences in patient and disease characteristics for NHB patients deserve further investigation into mechanisms underlying LBCL cancer biology by ancestry.3 Environmental and lifestyle factors such as obesity and tobacco smoking, associated with increased comorbidities, are also important considerations.4 Locke and colleagues highlight the comorbidity burden across racial/ethnic groups. Sixty-one percent of NHB patients had clinically significant comorbidities, as indicated by a hematopoietic cell transplantation–specific comorbidity score ≥2, compared with 40% for Hispanic patients, 41% for NHA patients, and 52% for NHW patients. They also had significantly higher moderate-severe pulmonary comorbidity (NHB vs Hispanic vs NHA vs NHW patients: 41% vs 20% vs 18% vs 29%, respectively). The higher comorbidity burden for NHB patients may account for the lower clinical trial referrals and participation.5 In addition, it may contribute to referral bias and lag in referrals for standard-care axi-cel.

The question of equitable access for NHB communities is an important one. In the study, NHB patients had the lowest representation in real-world and clinical trial populations with axi-cel compared with all other races/ethnicities, similar to trends described in other work.6 The authors point out that the NHB patient representation of around 5% in the real-world and clinical trial settings was lower than expected based on incidence reported in the SEER database, whereas representation of Hispanic, NHW, and NHA patients aligned more closely with predicted incidence. This may be explained by access barriers, particularly those affecting the NHB community.6 CAR-T therapy is a potentially curative approach, but demands a significant up-front investment of patients’ time, money, and caregiver support, often making it inaccessible to many from lower socioeconomic strata. Because race is strongly associated with socioeconomic status, these complexities tend to disproportionately affect NHB populations.6 Moreover, this specialized care is limited by the number of medical centers that can administer CAR-T therapy. This adds the additional burden of travel and/or relocation to specialized centers. Shahzad et al reported that 20 states had no active CAR-T therapy or bispecific antibody trials.7 Only 33% of Black patients lived in a county with a trial, and 7 of 10 states with the highest proportion of Black residents had no or less than 4 trial sites.7

Finally, other barriers include gaps in referring oncologists’ and patients’ education about CAR-T therapy. Although not explored by Locke et al, cultural mistrust of the medical establishment is also an obstacle to the NHB population's ability to benefit from this cutting-edge treatment. Referral bias and misinformation about the therapies may also factor into the lack of or delayed referrals.8

So, how can we translate insights from this report into developing strategies to improve outcomes for NHB patients? The most important step is fostering partnerships with referring oncologists to increase awareness and education about CAR-T therapy. The safety and efficacy findings from the study and similar reports support more tailored and targeted education efforts directed at referring physicians and patients. Exploring innovative strategies to reduce patients' physical and financial barriers should also be pursued, such as defining the optimal duration for caregiver support, relocation, and driving restriction requirements.9 Close partnerships with community practices may facilitate a safe and possibly earlier transition back to the community after infusion. Other strategies include engaging patient advocacy and support groups to educate communities about the indications for and processes of CAR-T therapy. Similarly, innovative approaches to increase clinical trial enrollment must be explored, especially with community physician engagement in satellite clinics and cooperative groups for enrollment and monitoring for postinfusion toxicity. Advocacy for CAR-T therapy and collaborations with industry, payers, regulatory agencies, and government to decrease the financial burden on patients will ultimately help increase access to CAR-T therapy for NHB patients. Many of these efforts are ongoing, and the study by Locke and colleagues serves as a benchmark to gauge the outcomes of current trials and pilot programs to increase access and decrease racial disparities.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: N.A. has served on the advisory board of Bristol Myers Squibb and has received consultancy fees and institutional research support from Kite/Gilead. W.W. declares no competing financial interests.