Abstract

Human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (hGM-CSF ) activates a set of genes such as c-fos, jun, myc, and early growth response gene 1 (egr-1). Studies on BA/F3 cells that express hGM-CSF receptor (hGMR) showed that two different signaling pathways controlled by distinct regions within the β subunit are involved in activation of c-fos/c-jun genes and in c-myc, respectively. However, the region(s) of the β subunit responsible for activation of the egr-1 gene and other regulatory genes has not been identified. We describe here how egr-1 promoter is activated by hGMR through two regions of the β subunit, with these regions being required for activation of the c-fos promoter. Coexpression of dominant negative (dn) Ras (N17ras) or dn JAK2 almost completely suppressed the activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters. Deletion analysis of egr-1 promoter showed two cis-acting regions responsible for activation by hGM-CSF or mouse interleukin-3 (mIL-3), one between nucleotide positions (nt) −56 and −116, and the other between nt −235 and −480, which contains tandem repeats of the serum response element (SRE) sites. Similar experiments with the c-fos promoter showed that cis-acting regions containing the SRE/AP-1 sites is sufficient for activation by hGM-CSF. Based on these observations, we propose that signaling pathways activating egr-1 and c-fos promoters are controlled by SRE elements, either through the same or overlapping pathways that involve JAK2 and Ras.

GRANULOCYTE-MACROPHAGE colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF ) stimulates growth and differentiation of hematopoietic cells.1 Human GM-CSF receptor (hGMR) consists of two subunits, α and common β (βc), and both belong to the cytokine receptor superfamily.2 We and others have reported that reconstituted hGMR in BA/F3 cells, as well as NIH3T3 cells, transduces signals to activate c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc genes and DNA replication.3,4 We further analyzed the signal transduction mechanism of hGMR by expressing various mutants of βc in BA/F35,6 and found that there are at least two distinct signaling pathways activated by the hGMR that use distinct regions of the βc. One pathway for activation of c-myc transcription and cell proliferation requires the region βc, which covers amino acid positions 455 to 489 proximal to the transmembrane domain.7,8 The other pathway for activation of c-fos and c-jun transcriptions requires a region between amino acids 544 to 589, which is located distal to the transmembrane region, in addition to the membrane proximal region.6 Furthermore, the induction of c-fos and c-jun in response to interleukin-3 (IL-3) or GM-CSF is not inhibited by the tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein, whereas c-myc activation and cell proliferation are completely suppressed. This indicates that the signaling pathway that leads to c-myc activation and DNA replication is likely to be independent of the signaling pathway for the induction of c-fos and c-jun mRNAs. We also noted the essential role of JAK2, which interacts in the membrane proximal region in βc for both signaling pathways.9 In contrast to c-fos, less is known of signaling mechanisms responsible for cell proliferation and activation of the c-myc gene. IL-3 or GM-CSF has been shown to activate or phosphorylate signaling molecules such as Ras, Raf, and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases.10-13 It is likely that the MAP kinase cascade that has been shown to activate c-fos in fibroblasts is also involved in c-fos gene activation in BA/F3 cells. Experiments using dominant negative (dn) types of signaling molecules support this hypothesis. To delineate the role of the membrane distal region of the βc on c-fos activation, we prepared several mutants of βc. Substitutions of tyrosine residues of βc with phenylalanine demonstrated that specific tyrosine residues in βc are responsible for c-fos promoter activation.14

In addition to induction of c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc genes and cell proliferation, GM-CSF activates a number of cellular genes, such as early growth response gene 1 (egr-1), Id-1, and cyclin D2, D3.15,16 However, the signals required for activation of these genes are unknown. The egr-1 is a transcription factor that encodes three zinc finger motifs and activates transcription of target genes.17,18 The role of egr-1 has been implicated in differentiation of myeloblast or myeloid cell lines along with macrophage19 or megakaryocyte20 lineages. GM-CSF or IL-3 rapidly and transiently induces egr-1 in differentiating and proliferating myeloid cells.21 22 However, the significance of the activation of egr-1 gene in GM-CSF function is not known.

Sakamoto et al investigated transcriptional regulatory regions involved in activation of egr-1 in response to GM-CSF or IL-3 stimulation in the human leukemia cell line TF-1 using a transient expression of reporter constructs containing sequences of the human egr-1 promoter.23 However, signals of hGMR involved in egr-1 gene induction have not been examined. In the present work, we examined the sequences of human egr-1 promoter responsible for hGM-CSF– or mIL-3–induced gene expression in BA/F3 cells expressing hGMR, and defined the regions within the βc of hGMR necessary for transcriptional activation of egr-1. We further examined signaling events that mediate egr-1 gene induction using dn forms of JAK and Ras.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and cells.Recombinant hGM-CSF and mouse IL-4 (mIL-4) produced in Escherichia coli were provided by Dr R. Kastelein, DNAX Research Institute. mIL-3 produced by silkworm, Bombyx mori, was purified as described.24 α[32P]-dCTP and [3H]-acetyl CoA were from Amersham Japan (Osaka, Japan). Chloramphenicol and genistein were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan), and herbimycin and fetal calf serum (FCS) from GIBCO Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). RPMI 1640 was obtained from Nikken Bio Medical Laboratory (Kyoto, Japan).

A mIL-3–dependent pro-B–cell line, BA/F3, was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 1 ng/mL mIL-3, 5% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Construction.egr480CAT lacking sequences between −56 to −116 (egr480Δ56-116) was constructed as follows: the fragment that contained egr-1 promoter sequences up to −56 and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) coding region were isolated by the Nco I site and Ava II sites of egr56CAT plasmid. The Ava II site was blunt-ended using the Klenow fragment before digestion by Nco I. The fragment that contained the egr-1 promoter between −116 and −480 and the vector portion was isolated by the Nco I site and Apa I site from the egr480CAT plasmid. The Apa I site was blunt-ended using T4 polymerase before digestion by Nco I. Both fragments were ligated using a Takara ligation kit version II (Takara Biomedical, Shiga, Japan). The construction of other plasmids that contained the egr-1 promoter-CAT were as described elsewhere.23

The series of CAT plasmids containing various length of c-fos promoter were gifts from Dr I. Verma and Dr M. Fujii.25,26 The 0.4-kb c-fos promoter fragment fused to luciferase was as described earlier.4

JAK1 cDNA (pBSK-JAK1) and JAK2 cDNA (pBSK-JAK2) were kindly provided by Dr J. Ihle (St Jude Children's Research Hospital). Construction of the plasmid containing wild-type JAK2 or dn JAK2 (ΔJAK2) under the control of the SRα promoter was performed as described elsewhere.9 dn JAK1 (ΔJAK1) was constructed as follows: ΔJak1, which lacks the C-terminus kinase domain, was isolated at the EcoRI and Sac I (2930) sites and the Sac I site was blunt-ended by the T4 polymerase before EcoRI digestion. The fragment was inserted at the blunt-ended Not I site and intact EcoRI site of pME18S.

The dn ras gene (MMTV promoter-N17 Ras; pMT64AA)27 was kindly provided by Dr G.M. Cooper (Harvard Medical School). Construction of a plasmid containing N17 Ras under the control of the SRα promoter was performed as described elsewhere.9 MMTV promoter-Ras12V was kindly provided by Dr Yokoyama (Tokyo University).

Northern blot analysis.BA/F3 cells or those transfectants that stably expressed hGMR (1 ×107 cells/sample) were factor-starved of mIL-3 for 5 hours and stimulated with hGM-CSF or mIL-3 (5 ng/mL) for the indicated times. Total cellular RNA was prepared by the guanidinium thiocyanate extraction method. RNA (10 μg each) was denatured by incubating at 65°C for 15 minutes, and separated by electrophoresis through a 1.2% agarose gel containing 6% formaldehyde, transferred to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham, UK) by capillary blotting, and immobilized by ultraviolet cross-linking. Mouse egr-1 cDNA was labeled with 32P by random priming and hybridized. Blots were washed and placed on an imaging plate for 12 hours. The plate was visualized using a Fuji image analyzer (model BAS-2000; Fuji, Kanagawa, Japan).

Transfection of cells.BA/F3 cells (1 × 106/sample) were transfected with DNA plasmids by electroporation, as described previously.7 The amounts of plasmids were 2 μg of egr-CAT and 3 μg of c-fos luciferase. Coexpressed plasmids such as JAK2 or Ras are indicated in the figure legends. In cotransfection experiments, the total amount of transfected DNA was adjusted by adding control vector plasmids. Cells were then resuspended in growth factor–free RPMI media (10 mL in 10-cm plates/sample) and cultured in the CO2 incubator for 5 hours. Dexamethasone (final concentration, 2 μmol/L) was added to the media when MMTV-Ras12V was used in experiments. Cells were stimulated with 5 ng/mL hGM-CSF or mIL-3 for 5 hours. In the experiments that used a kinase inhibitor, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of genistein for 15 minutes before stimulation. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 130 μL of 0.25 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Cells were lysed by three cycles of freeze and thawing and centrifuged for 5 minutes using a microfuge. Supernatants were divided into three portions and 100-μL aliquots were used for CAT assays, 10-μL aliquots for luciferase assays, and 20 μL for protein estimation. CAT and luciferase assay were performed as previously described.4,7 28 The amount of protein was estimated using BCA kits (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein estimation was duplicated and average values were used. Luciferase activity was expressed in terms of the luminescence intensity (relative light unit [RLU]) per protein. The results are averages of three samples with the standard deviations being indicated by error bars.

RESULTS

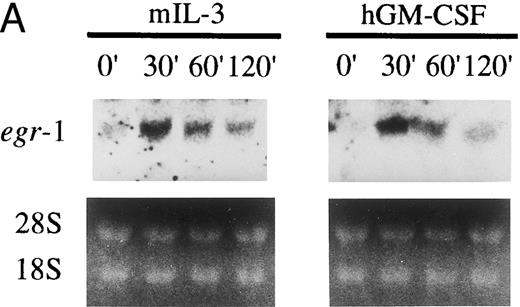

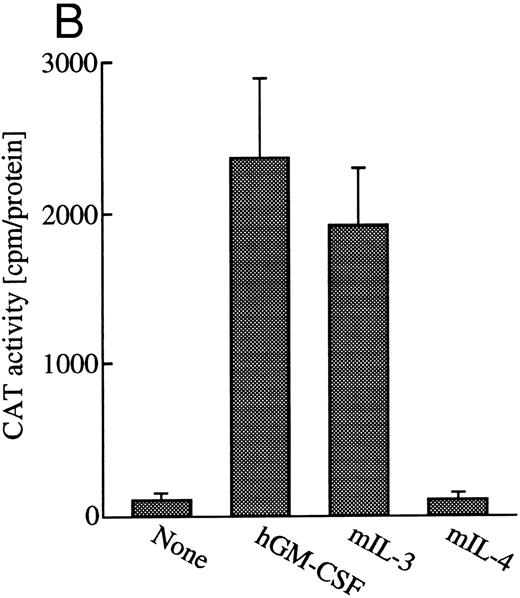

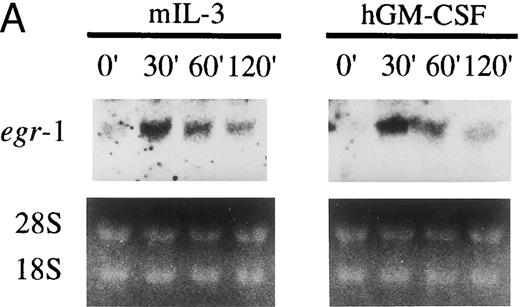

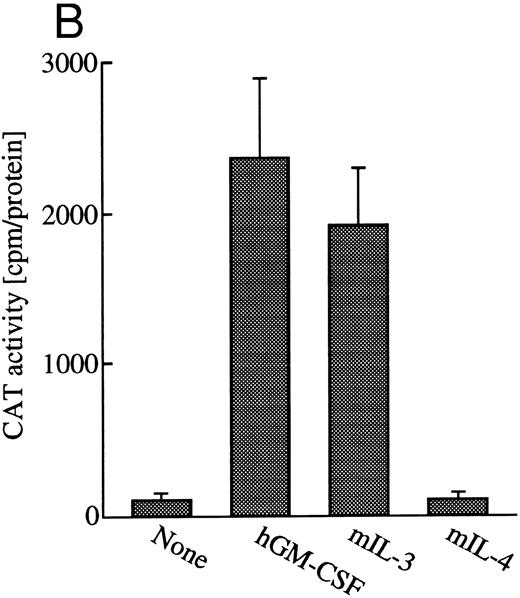

GM-CSF or IL-3 activates human egr-1 promoter in BA/FGMR cells. egr-1 is rapidly and transiently induced by GM-CSF in both proliferating and terminally differentiated myeloid cells.15 We first examined induction of egr-1 mRNA by the endogenous IL-3 receptor (mIL-3R) and transfected hGMR in BA/FGMR cells (BA/F3 cell expressing wild-type hGMR α and β subunits). Cells were stimulated with mIL-3 or hGM-CSF for 0, 30, 60, or 120 minutes after 5 hours of factor starvation, and total RNA was subjected to Northern blot analysis. Kinetics of induction of egr-1 mRNA by hGM-CSF peaked at 30 minutes and decreased afterwards (Fig 1A). mIL-3 stimulation resulted in activation of the egr-1 gene in kinetics similar to that by hGM-CSF. We next examined hGM-CSF/mIL-3–induced egr-1 promoter activity using egr600CAT, which contains nucleotides (nt) −606 to +8 of the human egr-1 promoter.28 To assess its activity in BA/FGMR, cells were transiently transfected with egr600CAT and subjected to CAT assay after stimulation with 5 ng/mL of hGM-CSF, mIL-3, or mIL-4. mIL-3 or hGM-CSF stimulation resulted in a marked increase in CAT activity (Fig 1B). On the other hand, mIL-4 elicited no enhanced ability. Taken together, these results indicate that GM-CSF or IL-3 stimulates the egr-1 promoter in BA/F3 cells.

Induction of transcription of egr-1 by mIL-3 or hGM-CSF in BA/FGMR cells. (A) Induction of egr-1 mRNA was analyzed by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA of BA/FGMR cells stimulated by either mIL-3 or hGM-CSF at the indicated time was subjected to Northern blot analysis using egr-1 cDNA fragment as a probe. (B) Plasmid-containing egr-1 promoter fragment (nts ;k2606 to ;k18) fused to CAT coding region was transfected to BA/FGMR cells, and CAT activities induced by either mIL-3, hGM-CSF, or mIL-4 were analyzed by diffusion analysis, as described in the Materials and Methods.

Induction of transcription of egr-1 by mIL-3 or hGM-CSF in BA/FGMR cells. (A) Induction of egr-1 mRNA was analyzed by Northern blot analysis. Total RNA of BA/FGMR cells stimulated by either mIL-3 or hGM-CSF at the indicated time was subjected to Northern blot analysis using egr-1 cDNA fragment as a probe. (B) Plasmid-containing egr-1 promoter fragment (nts ;k2606 to ;k18) fused to CAT coding region was transfected to BA/FGMR cells, and CAT activities induced by either mIL-3, hGM-CSF, or mIL-4 were analyzed by diffusion analysis, as described in the Materials and Methods.

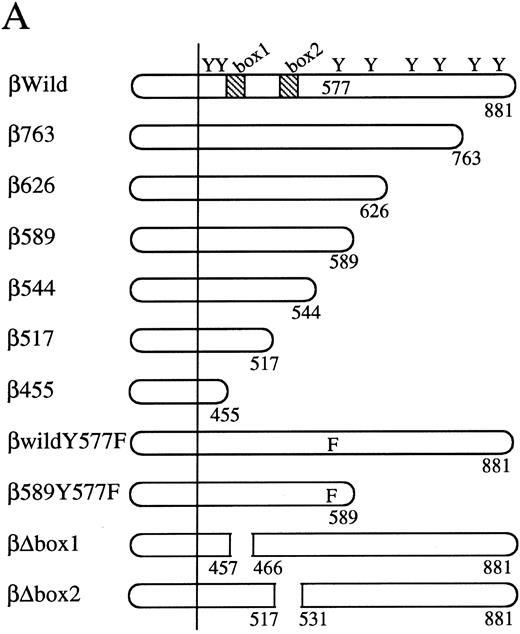

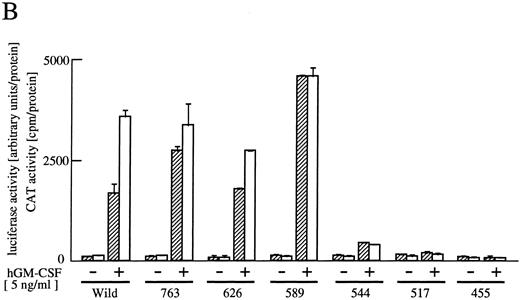

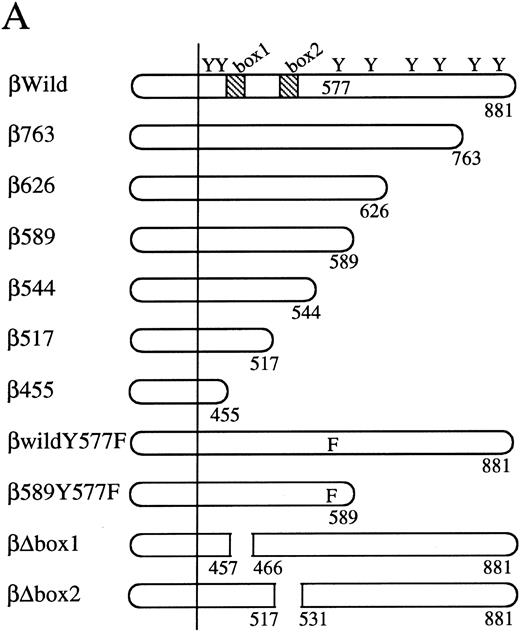

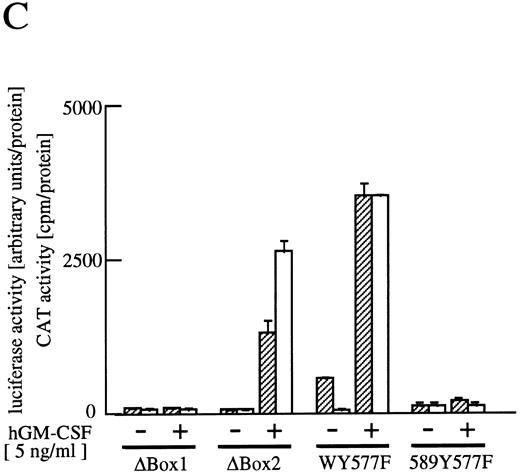

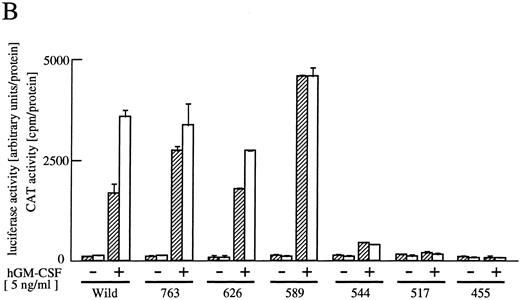

The cytoplasmic region of βc required for activation of egr-1 promoter.To examine signaling events that lead to activation of egr-1 gene by hGM-CSF, we defined regions within the βc that are required for activation of egr-1 promoter, using a series of cytoplasmic deletion mutants of βc (Fig 2A).5,6 To compare the requirement of region(s) within βc for c-fos promoter activation, c-fos promoter-luciferase plasmid4 was cotransfected with the egr600CAT plasmid, the wild-type hGMRα subunit, and wild-type or truncated βc into BA/F3 cells, and luciferase and CAT activities were analyzed (Fig 2B). Mutants of βc used in the experiments are schematically represented in Fig 2A. Deletion of βc from the carboxy terminus up to 589 did not affect GM-CSF–induced egr600CAT activity, but the activity was greatly reduced when βc was truncated up to position 544. Further deletion up to position 517 completely abolished the response to hGM-CSF. The membrane proximal region contains box1 and box2 motifs, which are conserved among several cytokine receptors.29 To examine the role of these motifs in GM-CSF–induced activation of egr-1, we next analyzed activity of the egr-1 promoter induced in cells that expressed mutant βc lacking either box1 or box2 motif 9,14 (Fig 2A and C). An internal deletion of the region covering amino acids 458 to 465, which contains box1, resulted in complete loss of hGM-CSF–induced egr-1 transcriptional activation. On the other hand, deletion of the region that contained box2 (amino acid positions 518 to 530) did not affect GM-CSF–induced egr-1 promoter activity. The C terminal side of βc contains several tyrosine residues. Tyr577 is the only tyrosine residue within the region that contains amino acids 544 to 589, which are required for egr-1 gene activation. We then analyzed the requirement of tyr577 for egr-1 promoter activity, using a mutant in which phenylalanine is substituted for tyr577. As shown in Fig 2C, this substitution of tyr577 of hGMRβ589 resulted in complete loss of egr-1 transcriptional activation. In contrast, the same substitution with wild-type βc did not affect the GM-CSF–induced activation of egr-1. Thus, tyr577 seems to be essential for mutant 589, but other tyrosine residue(s) may substitute for tyr577. It appears that the requirements of receptor regions for egr-1 gene activation are essentially the same as that for c-fos. We next examined the signal transduction pathways that lead to the activation of egr-1 promoter in comparison to c-fos gene activation.

Analysis of activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters through various hGMR mutants in BA/F3 cells. egr600CAT plasmid and c-fos-luciferase plasmid were transfected to BA/F3 cells expressing the wild-type hGMR;ga subunit and mutant ;gbc. Mutants of ;gb subunit are schematically shown in (A). CAT activities (▨) or luciferase activities (;bb) induced by hGM-CSF were analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) The C terminus truncated mutants from amino acid positions 455 to 763, or (C) internal deletions of either box1 or box2 of wild-type ;gbc or phenylalanine substitution of tyr577 of ;gb589 or wild-type ;gbc were used.

Analysis of activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters through various hGMR mutants in BA/F3 cells. egr600CAT plasmid and c-fos-luciferase plasmid were transfected to BA/F3 cells expressing the wild-type hGMR;ga subunit and mutant ;gbc. Mutants of ;gb subunit are schematically shown in (A). CAT activities (▨) or luciferase activities (;bb) induced by hGM-CSF were analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) The C terminus truncated mutants from amino acid positions 455 to 763, or (C) internal deletions of either box1 or box2 of wild-type ;gbc or phenylalanine substitution of tyr577 of ;gb589 or wild-type ;gbc were used.

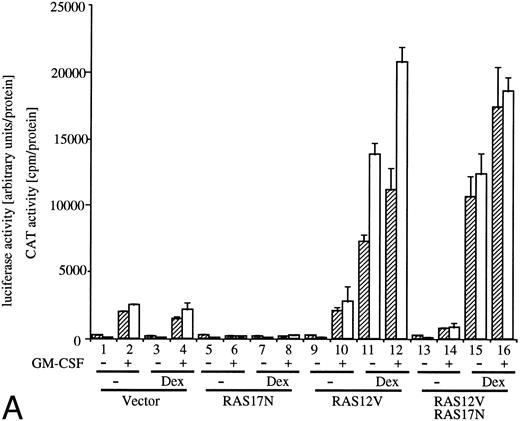

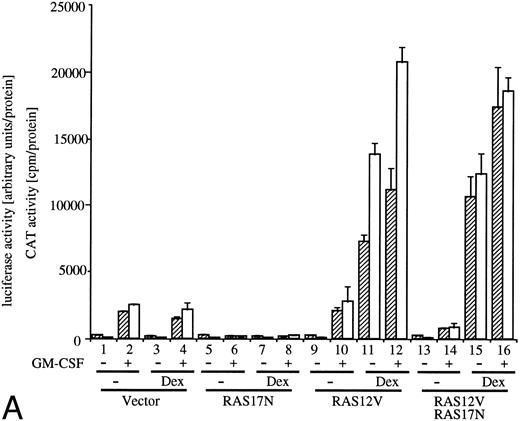

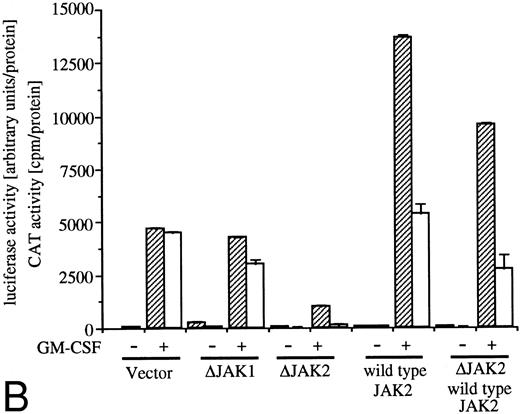

Effects of dn JAK1, JAK2, and Ras.GM-CSF activates signal transduction pathways composed of Ras, Raf-1, and MAP kinase.10-13 Coexpression of a dn mutant of Ras (Ras17N) completely suppressed IL-3– or GM-CSF–induced c-fos promoter activity.9 We then examined the effect of Ras17N expression on egr-1 reporter plasmids. c-fos-luciferase and egr600CAT were transfected with either a vector control or SRαRas17N to BA/FGMR cells (Fig 3A, columns 1, 2, 5, and 6). Expression of the Ras17N almost completely suppressed activation of both egr-1 and c-fos promoters by hGM-CSF. Essentially the same results were obtained with mIL-3 stimulation (data not shown). We next examined whether coexpression of activated Ras (Ras12V) affected egr-1 and c-fos promoter activities. When MMTV-Ras12V was transfected with egr600CAT and c-fos-luciferase, these promoter activities were strongly augmented by addition of dexamethasone, which activates MMTV promoter (Fig 3A, columns 9 through 12). Cotransfection of MMTV-Ras12V plasmids with SRαRas17N resulted in no suppression of egr-1 and c-fos promoter activities by SRαRas17N (Fig 3A, columns 13 through 16).

Analysis of signaling events leading to activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters. (A) Effects of dn Ras on hGM-CSF=ninduced activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters. The egr600CAT (3 ;gmg) and c-fos-luciferase (2 ;gmg) plasmids were transfected to BA/FGMR cells either alone or in combination with 5 ;gmg of SR;ga-Ras17N, MMTV-Ras12V, or vector. Cells were divided to 6 samples and resuspended in mIL-3 free media with or without dexamethasone (final, 2 ;gmmol/L) after transfection. Cells were cultured for 5 hours and then stimulated with 5 ng/mL of hGM-CSF. CAT (▨) and luciferase (;bb) activities were analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Effects of ;gDJAK1 or ;gDJAK2 on activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters by hGM-CSF. Either alone or in combination with ;gDJAK1, ;gDJAK2, or wild-type JAK2, plasmids were transfected with egr600CAT and c-fos-luciferase plasmids. After depletion of mIL-3 for 5 hours, cells were stimulated for 5 hours with hGM-CSF (5 ng/mL) and were harvested. CAT (▨) and luciferase (;bb) activities were analyzed as described.

Analysis of signaling events leading to activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters. (A) Effects of dn Ras on hGM-CSF=ninduced activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters. The egr600CAT (3 ;gmg) and c-fos-luciferase (2 ;gmg) plasmids were transfected to BA/FGMR cells either alone or in combination with 5 ;gmg of SR;ga-Ras17N, MMTV-Ras12V, or vector. Cells were divided to 6 samples and resuspended in mIL-3 free media with or without dexamethasone (final, 2 ;gmmol/L) after transfection. Cells were cultured for 5 hours and then stimulated with 5 ng/mL of hGM-CSF. CAT (▨) and luciferase (;bb) activities were analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Effects of ;gDJAK1 or ;gDJAK2 on activation of egr-1 and c-fos promoters by hGM-CSF. Either alone or in combination with ;gDJAK1, ;gDJAK2, or wild-type JAK2, plasmids were transfected with egr600CAT and c-fos-luciferase plasmids. After depletion of mIL-3 for 5 hours, cells were stimulated for 5 hours with hGM-CSF (5 ng/mL) and were harvested. CAT (▨) and luciferase (;bb) activities were analyzed as described.

JAK family kinases have been shown to play a role in cytokine receptor signaling.30 GM-CSF stimulates phosphorylation of JAK1 and JAK2 in BA/F3 cells and JAK2 plays an essential role in all known GM-CSF signaling events, including c-fos promoter activation.9 To elucidate roles of JAK1 or JAK2 in egr-1 activation in BA/FGMR cells, we examined effects of dn JAK1 (ΔJAK1) or JAK2 (ΔJAK2) on egr-1 promoter activity induced by IL-3 or GM-CSF. Mutant JAK1 lacking the C terminal kinase domain inhibited autophosphorylation of wild-type JAK1 when these genes were coexpressed in COS7 cells (data not shown). The same JAK2 mutant also acts in a dn manner to prevent autophosphorylation of wild-type JAK2.9 Expression of ΔJAK1 slightly reduced GM-CSF–induced egr-1 and c-fos expression, whereas ΔJAK2 completely suppressed egr-1 and c-fos promoter activity (Fig 3B). By addition of SRα–wild-type JAK2, c-fos promoter activity was slightly augmented, whereas egr-1 promoter was greatly augmented under this condition. Cotransfection of wild-type JAK2 with ΔJAK2 recovered both c-fos and egr-1 promoter activities. These results indicate that JAK2 plays an essential role in egr-1 activation in response to GM-CSF.

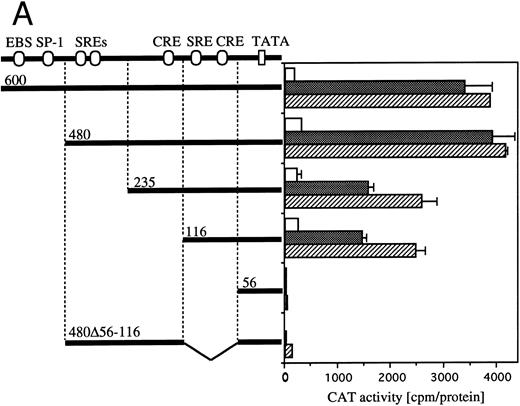

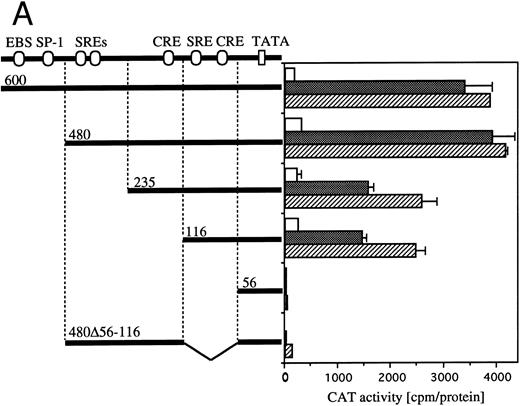

Definition of cis-acting sequence(s) of egr-1 and c-fos promoter responding to hGM-CSF or mIL-3.The human egr-1 promoter contains several putative recognition sites for transcriptional regulatory proteins. We previously identified cis-sequences of egr-1 promoter that respond to hGM-CSF stimulation in TF-1 cells using various 5′ deletion mutants of egr promoter CAT plasmids.23 We next identified the sequences of the egr-1 promoter responding to GM-CSF– or IL-3–activated signals in BA/FGMR cells. We transfected various deletion mutants of egr600CAT into BA/FGMR cells. egr480, 235, 116, and 56 contain 480-, 235-, 116-, and 56-nt length fragments of egr-1 promoter from the transcription start site, respectively28 (Fig 4A). The egr480CAT showed an activity slightly greater than that observed with the egr600CAT in response to hGM-CSF or mIL-3. This response was markedly reduced by deletion of nt down to −235. Further deletion to nt −116 did not affect CAT activity, and an additional 60-nt deletion to nt −56 completely abolished the response. These results suggest sequences that contain SREs distal to the transcriptional starting site and SRE/CRE proximal to the transcriptional starting site are required for hGM-CSF– or mIL-3–induced egr-1 transcriptional activation. To determine whether the region that contains proximal SRE/CRE is essential, we deleted the region including nts 56 to 116 of egr480CAT (egr480Δ56-116). egr480Δ56-116CAT showed no appreciable CAT activity in response to either GM-CSF or IL-3 stimulation. These results suggest that the region covering −56 to −116 is essential for activation of egr-1 promoter in response to IL-3 or GM-CSF in BA/FGMR cells and region nts −235 to −480 have enhancing activity. These results also suggest that sequences that contain the SREs distal to the transcriptional start site and SRE/CRE proximal to the transcriptional starting site are required for hGM-CSF– or mIL-3–induced egr-1 transcriptional activation in BA/FGMR cells. In contrast, requirement of the distal SREs site was not observed by either hGM-CSF or mIL-3 stimulation in TF-1 cells.23

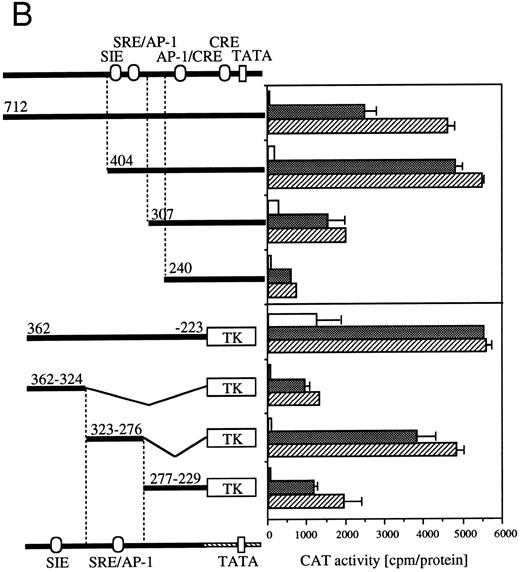

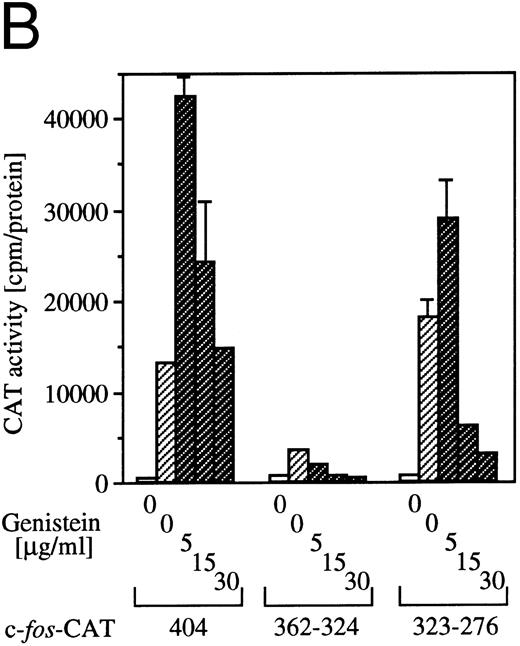

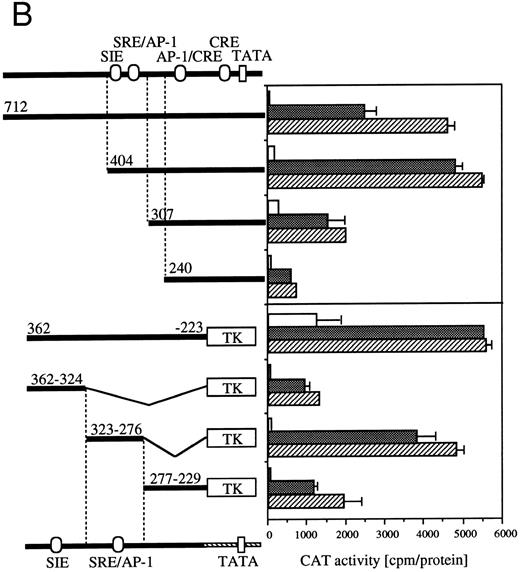

Requirement of cis-sequence of egr-1 and c-fos promoter for IL-3=n or GM-CSF=ninduced transcriptional activation. (A) Various egr-1 promoter CAT constructs were transfected into BA/FGMR cells and cells were stimulated with either mIL-3 or hGM-CSF. (B) Upper panel: plasmids with various lengths of the c-fos promoter fused to the CAT coding region were transfected into BA/FGMR cells. The CAT activities induced by mIL-3 or hGM-CSF were analyzed by diffusion analysis. Lower panel: CAT activities induced by IL-3/GM-CSF in BA/FGMR cell of the c-fos promoter fragments fused to TK-minimal promoter and CAT coding region were analyzed as described. CAT activities induced by mIL-3 () or hGM-CSF (▨) were analyzed by diffusion analysis. (;bb) CAT value of unstimulated cells (A and B).

Requirement of cis-sequence of egr-1 and c-fos promoter for IL-3=n or GM-CSF=ninduced transcriptional activation. (A) Various egr-1 promoter CAT constructs were transfected into BA/FGMR cells and cells were stimulated with either mIL-3 or hGM-CSF. (B) Upper panel: plasmids with various lengths of the c-fos promoter fused to the CAT coding region were transfected into BA/FGMR cells. The CAT activities induced by mIL-3 or hGM-CSF were analyzed by diffusion analysis. Lower panel: CAT activities induced by IL-3/GM-CSF in BA/FGMR cell of the c-fos promoter fragments fused to TK-minimal promoter and CAT coding region were analyzed as described. CAT activities induced by mIL-3 () or hGM-CSF (▨) were analyzed by diffusion analysis. (;bb) CAT value of unstimulated cells (A and B).

Because signaling events that mediate c-fos and egr-1 transcriptional activation are not separable, we next analyzed cis-acting elements of c-fos promoter that respond to IL-3 or GM-CSF stimulation (Fig 4B). The c-fos luciferase construct used in the present work contains the 404-nt fragment from the transcriptional starting site of c-fos promoter region. The plasmid that contains the 712-nt promoter fragment shows almost the same or somewhat reduced CAT activities in response to IL-3 or GM-CSF compared with that observed with the −404 CAT plasmid. Deletion of sequences up to nt −307 reduced significantly IL-3–/GM-CSF–induced luciferase activity. Further deletion up to nt −240 further reduced the activity. We next performed a detailed analysis of required promoter region nucleotides using several plasmids that contained sequences within nt −362 to −223 of c-fos promoter fused to the herpes virus thymidine kinase promoter (TK) and the CAT coding region.26 We first asked if nts −404 to −240 are sufficient for induction by IL-3 or GM-CSF using a −362 to −223 fragment fused to TK-CAT. As shown in Fig 4B, the −362 to −223 plasmid responded to IL-3 or GM-CSF, although higher background activity was observed with unstimulated cells. There are three known transcription factor recognition sites in nts −362 to −223: c-sis–inducible element (SIE), SRE, and AP-1. The SRE and AP-1 sites overlap and are inseparable.31 The fragment containing only the SIE site (nts −362 to −324) showed a relatively low response to IL-3 or GM-CSF. In contrast, the region between nts −323 to −276, which contains SRE/AP-1 sites, responded to IL-3 or GM-CSF. Fragment of nts −277 to −229 responded, but at a relatively low level, to IL-3 or GM-CSF.

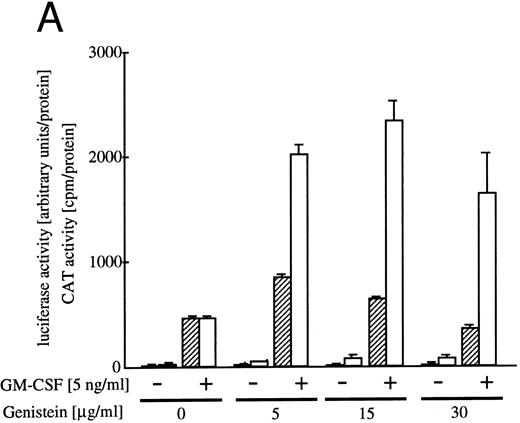

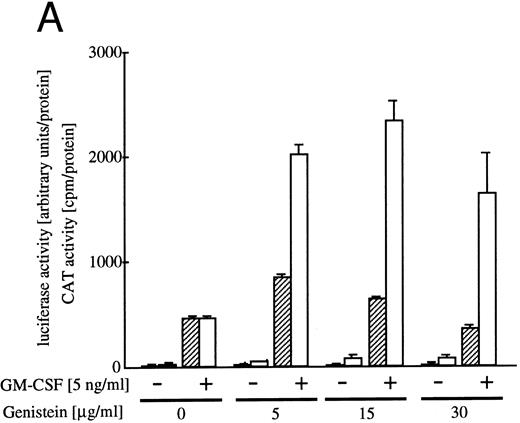

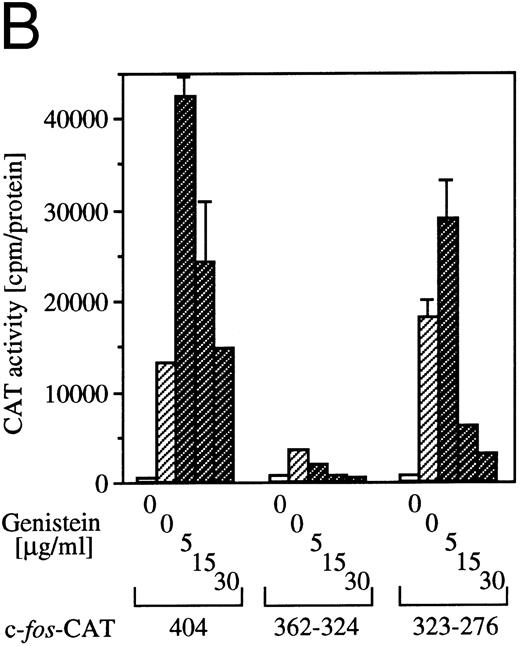

Effect of tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein on egr-1 and c-fos transcriptional activation.Genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, affects tyrosine kinases, including the EGF receptor, pp60-v-src and pp110gag-Fes.32 We reported earlier that genistein superinduced c-fos transcription, but suppressed c-myc gene transcription or proliferation.6 The genistein-induced augmentation of the activation of c-fos promoter is not likely to be due to suppression of the degradation pathway of the mRNA, because genistein enhanced c-fos transcription, as well as c-fos-luciferase reporter activity.6 To examine the effect of genistein on activation of egr-1 promoter, BA/FGMR cells were transfected with c-fos-luciferase and egr600CAT, and the CAT and luciferase activities induced by GM-CSF in the presence of genistein were analyzed (Fig 5A). Genistein did augment c-fos promoter activation by hGM-CSF. GM-CSF–induced activity of the egr-1 promoter was also enhanced by genistein, but appeared weaker than that seen with the c-fos promoter. Essentially the same results were obtained with IL-3 stimulation (data not shown).

Effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein on egr-1 and c-fos promoter activities in BA/FGMR cells. (A) egr600CAT and c-fos-luciferase plasmids were transfected into BA/FGMR cells and the indicated concentrations of genistein were added to cells 30 minutes before stimulation. hGM-CSF=ninduced CAT activities (▨) and luciferase activities (;bb) were analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Effects of genistein on various c-fos-CAT plasmid activities. The c-fos-TK-CAT plasmids were transfected into BA/FGMR cells and the effects of genistein were analyzed. The white bar indicates CAT value of unstimulated cells, and GM-CSF=ninduced CAT activities with () or without (▨) genistein were represented.

Effects of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor genistein on egr-1 and c-fos promoter activities in BA/FGMR cells. (A) egr600CAT and c-fos-luciferase plasmids were transfected into BA/FGMR cells and the indicated concentrations of genistein were added to cells 30 minutes before stimulation. hGM-CSF=ninduced CAT activities (▨) and luciferase activities (;bb) were analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Effects of genistein on various c-fos-CAT plasmid activities. The c-fos-TK-CAT plasmids were transfected into BA/FGMR cells and the effects of genistein were analyzed. The white bar indicates CAT value of unstimulated cells, and GM-CSF=ninduced CAT activities with () or without (▨) genistein were represented.

To further delineate the target of genistein, we analyzed the effects of genistein on plasmids containing the c-fos upstream fragment. As shown in Fig 5B, GM-CSF–induced CAT activities of c-fos promoter fragments fused to CAT plasmids containing SRE/AP-1 sites (nt −404, and −323 to −276) were augmented by low-dose genistein. In contrast, CAT activity of the plasmid containing the fragment with the SIE site (nt −362to −324) was suppressed by genistein. These results suggest that the target of genistein is located within the SRE/AP-1 site rather than the SIE site.

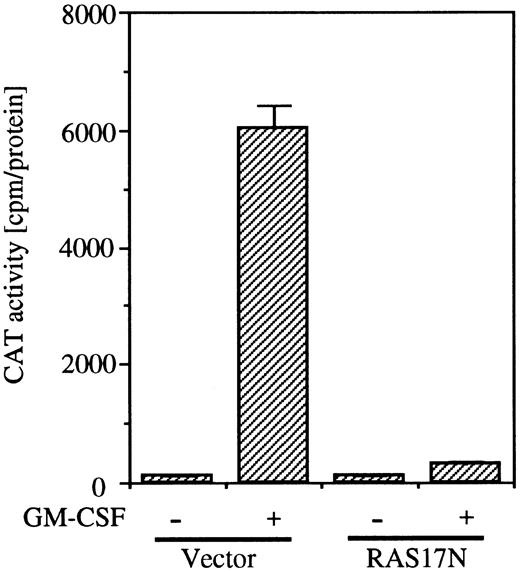

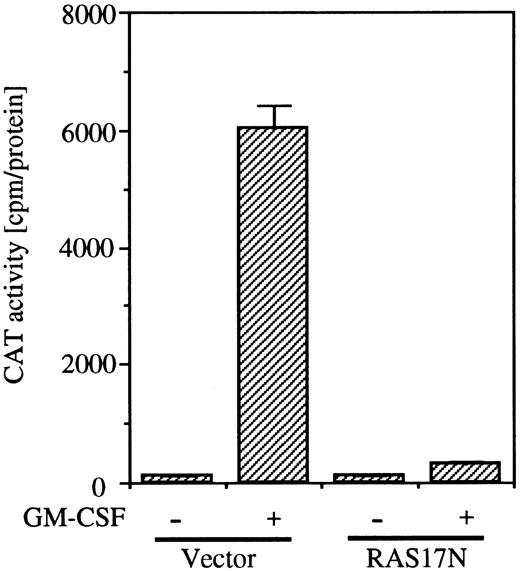

To examine whether the SRE/AP-1 site is in the downstream of the Ras pathway, we next analyzed the effect of coexpression of Ras17N with c-fos promoter fragment (nt −323 to −276) fused to the TK-CAT construct containing the SRE/AP-1 site. As shown in Fig 6, coexpression of Ras17N completely suppressed the c-fos CAT activity induced by GM-CSF.

Effects of dominant negative Ras on SRE/AP-1 activity of c-fos promoter induced by hGM-CSF. The c-fos promoter fragment (nt ;ms 323 to ;ms276) fused to TK-CAT plasmid was transfected to BA/FGMR cells with either SR;ga dn Ras or vector control plasmids. After depletion of mIL-3 for 5 hours, cells were stimulated with hGM-CSF for another 5 hours. CAT activity was analyzed by diffusion assay.

Effects of dominant negative Ras on SRE/AP-1 activity of c-fos promoter induced by hGM-CSF. The c-fos promoter fragment (nt ;ms 323 to ;ms276) fused to TK-CAT plasmid was transfected to BA/FGMR cells with either SR;ga dn Ras or vector control plasmids. After depletion of mIL-3 for 5 hours, cells were stimulated with hGM-CSF for another 5 hours. CAT activity was analyzed by diffusion assay.

DISCUSSION

In our earlier work, we obtained evidence for two distinct signaling pathways with hGMR.6,8 One pathway, which leads to activation of DNA replication and the c-myc gene, requires the transmembrane proximal region of βc. The other, which leads to activation of c-fos and c-jun genes, requires the transmembrane distal region in addition to the proximal region. We then investigated whether signaling pathways for induction of other genes by hGM-CSF could be classified into the two signaling pathways. We found that the transcriptional activation of ID1 and cyclin D2 genes induced by hGM-CSF required the membrane proximal region of βc (manuscript in preparation). In contrast, membrane distal regions, as well as membrane proximal regions, are required for GM-CSF–dependent activation of the egr-1 promoter. This requirement was the same as that for c-fos activation,6 14 which suggests that egr-1 and c-fos gene activation are coregulated by the same signaling pathways. Although mechanisms of c-myc induction and DNA replication are unknown, signaling events involved in c-fos activation are well documented. We took the strategy to investigate the mechanism that leads to activation of egr-1, in comparison to c-fos. We obtained evidence that c-fos and egr-1 promoters are regulated by the same or overlapping mechanism through the JAK and Ras signaling pathway leading to SRE activation by GM-CSF.

The membrane proximal region necessary to activate c-fos and egr-1 genes contains the box1 sequence, which is conserved among members of the cytokine receptor superfamily.29 What is the role of the membrane proximal region of βc to activate transcription of egr-1? Experiments using ΔJAK2 showed that JAK2 is essential to activate both egr-1 and the c-fos gene. We found that the box1 but not the box2 region is required for activation of JAK2, and that JAK2 is responsible for phosphorylation of βc.9 It can be speculated that the egr-1 gene is activated through SH2-containing signaling molecules, which interact with JAK2-dependent phosphorylation of the βc. We have previously examined the requirement of tyrosine residues for activation of c-fos gene and signal-transducing molecules,14 and obtained results demonstrating that tyr577 is essential for activation of Shc, whereas activation of Shc is not essential for c-fos activation. Because the domains within the βc required for activation of egr-1, c-fos promoters, and PTP1D appeared to be the same, and dn Ras almost completely suppressed the transcriptional activation of egr-1, as well as c-fos, through the hGMR, we speculate that PTP1D and Ras are involved in egr-1 activation. However, activation of Shc is not essential for egr-1 gene activation. Taken together, the two regions required for egr-1 gene induction can be explained by a model that JAK2 interacts with box1 leading to phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in more membrane distal regions. This results in SH2-containing proteins transducing signals to activate c-fos and egr-1 genes through ras/MAPK cascade.

Because the signaling events that lead to c-fos and egr-1 activation are indistinguishable, it is tempting to speculate that mechanisms for activation of these two genes are also similar or perhaps even the same. Deletion analysis of the human egr-1 promoter showed that the sequences responsible for transcriptional activation of egr-1 by hGMR were localized between −56 and −116 and −235 and −480 nt relative to the transcription start site in BA/F3 cells, a mouse pro–B-cell line. On the other hand, in the human erythroleukemic cell line, TF-1,23 hGM-CSF, or human IL-3 appear to stimulate the egr-1 promoter through a sequence located between nt −56 and −116 of egr-1 promoter. However, no enhancing effect was detected between nt −235 and −480 in TF-1 cells. Furthermore, the egr-1 autoregulatory binding site (EBS) located between nt −589 and −597 was found to be a GM-CSF–specific enhancer in TF-1 cells, which was not observed in the present study. The reason for this discrepancy is currently unknown, but we could speculate that TF-1 cells lack some factor(s) that is functional in BA/F3 and necessary for the function of the enhancer elements located between −235 and −480, or this enhancer element is constitutively activated in TF-1 cells.

Other investigators characterized mouse egr-1 promoter elements responding to various stimulations. v-Raf activation was attributed to the cluster of SRE located between −250 and −425.33 The sequences between nts 235 to 480 of the human egr-1 promoter are responsive to GM-CSF stimulation. Likewise, the same region is stimulated by v-Src,34 v-Fps,35 and ionizing radiation.36 Because src family tyrosine kinases, raf, or Fps are reported to be activated by IL-3 or GM-CSF stimulation,13,37 38 it may be that egr-1 was activated through these signaling molecules in response to GM-CSF stimulation.

CAT analysis suggests that the SRE/AP-1 site in the c-fos promoter is also essential for c-fos activation by hGM-CSF. We reported that IL-3 or GM-CSF induced binding of proteins to the AP-1 site in BA/F3 cells when the AP-1 site of the c-jun promoter was used as a probe.6 When we performed gel-shift analysis using oligonucleotide that contained the SRE/AP-1 site of the c-fos promoter, constitutive binding and no difference of binding features before and after stimulation with IL-3 or GM-CSF were observed in BA/F3 cells (data not shown). Neither binding of AP-1 nor c-jun transcriptional activation was sensitive to genistein (data not shown). These observations support the notion that AP-1 may not have a role in the c-fos promoter.

A canonical STAT binding site, SIE, did not appear to be necessary. Binding of STAT1 and STAT3 to the sites has been previously reported.39 We performed gel-mobility shift assays using the SIE site of the c-fos promoter, and no differences in the pattern of binding proteins were observed before and after stimulation by IL-3 or GM-CSF in BA/F3 cells (data not shown). Furthermore, although IL-3 or GM-CSF activates phosphorylation of STAT5 and its binding to the MGF binding site,40 we observed no phosphorylation of either STAT1 or STAT3 in response to IL-3 or GM-CSF in BA/F3 cells (data not shown). These results suggest that the SIE site of the c-fos promoter does not contribute to GM-CSF inducibility of c-fos promoter, even though this site may play a role in basal activity, because constitutive binding of proteins to the site was observed in the gel-mobility shift analysis (data not shown). The finding of a minor role for the SIE in c-fos promoter induction is in agreement with reports that demonstrated EGF-dependent c-fos activation in Hela cells41 or PDGF in 3T3 cells.42

How does GM-CSF activate egr-1 and c-fos promoters through the SRE sites? Because dn Ras completely suppressed GM-CSF–induced c-fos-promoter TK-CAT activity, which contains the SRE/AP-1 sites, involvement of Ras pathway in c-fos promoter activation by GM-CSF is suggested. Activation of SRE-binding proteins of the c-fos promoter by activated ras has been reported.43 It has been well documented that SRF binds to the SRE constitutively and forms ternary complexes with other proteins, including TCF, Elk-1, or SAP-1.44,45 Phosphorylation of Elk-1 by MAPK has also been reported.44 The mechanism of activation of c-fos and egr-1 may involve phosphorylation of the ternary complex of SRF. Further experiments to define each of the complexes binding to each SRE site in the c-fos and egr-1 promoters are required. Taken together, we conclude that the signals leading to the activation of egr-1 and c-fos share the same pathway that induces activation of Ras pathway and consequent SRE activation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr S.D. Nimer for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript, E. Akagawa for technical support, and M. Ohara for comments.

Supported in part by a grant-in-aid for scientific research on priority areas from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan.

Address reprint requests to Sumiko Watanabe, PhD, Department of Molecular and Developmental Biology, Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108, Japan.