Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the inhibitory effects of human leukocyte elastase (HLE), cathepsin G (Cat G), and proteinase 3 (PR3) on the activation of endothelial cells (ECs) and platelets by thrombin and to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Although preincubation of ECs with HLE or Cat G prevented cytosolic calcium mobilization and prostacyclin synthesis induced by thrombin, these cell responses were not affected when triggered by TRAP42-55, a synthetic peptide corresponding to the sequence of the tethered ligand (Ser42-Phe55) unmasked by thrombin on cleavage of its receptor. Using IIaR-A, a monoclonal antibody directed against the sequence encompassing this cleavage site, flow cytometry analysis showed that the surface expression of this epitope was abolished after incubation of ECs with HLE or Cat G. Further experiments conducted with platelets indicated that not only HLE and Cat G but also PR3 inhibited cell activation induced by thrombin, although they were again ineffective when TRAP42-55 was the agonist. Similar to that for ECs, the epitope for IIaR-A disappeared on treatment of platelets with either proteinase. These results suggested that the neutrophil enzymes proteolyzed the thrombin receptor dowstream of the thrombin cleavage site (Arg41-Ser42) but left intact the TRAP42-55 binding site (Gln83-Ser93) within the extracellular aminoterminal domain. The capacity of these proteinases to cleave five overlapping synthetic peptides mapping the portion of the receptor from Asn35 to Pro85 was then investigated. Mass spectrometry studies showed several distinct cleavage sites, ie, two for HLE (Val72-Ser73 and Ile74-Asn75), three for Cat G (Arg41-Ser42, Phe55-Trp56 and Tyr69-Arg70), and one for PR3 (Val72-Ser73). We conclude that this singular susceptibility of the thrombin receptor to proteolysis accounts for the ability of neutrophil proteinases to inhibit cell responses to thrombin.

THE ENDOTHELIUM is a strategic barrier at the interface between blood and underlying tissues, and modifications of its functions by thrombin are of a major importance in the hemostatic response and in proliferative and inflammatory processes. Thus, the effects of this plasma serine proteinase on endothelial cells (ECs) include prostacyclin (prostaglandin I2 [PGI2]) synthesis, secretion of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, and platelet-derived growth factor synthesis.1,2 Thrombin also induces the formation of platelet-activating factor, and the surface expression of P-selectin, two events that favor polymorphonuclear neutrophil adhesiveness to ECs3 and, subsequently, their degranulation.4 Among the constituents of neutrophils thus released are three serine proteinases, namely, human leukocyte elastase (HLE), cathepsin G (Cat G), and proteinase 3 (PR3),5 that, in turn, are able to affect ECs. In vitro experiments have indeed shown that HLE and Cat G induce detachment6 or even lysis of ECs.7,8 However, when used at low concentrations, these proteinases subtly modify EC functions involved in vasoregulation. From this point of view, Weksler et al9 interestingly showed that HLE and Cat G specifically suppressed the production of PGI2 and the increase of intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) induced by thrombin, an effect hypothesized at that time to result from the cleavage of a putative EC receptor for this agonist. Apart from its effects on ECs, thrombin is mostly known as a potent platelet agonist inducing shape change, internal granule exocytosis, and aggregation,10 thus playing a crucial role in the regulation of thrombosis and hemostasis.11 Among the neutrophil serine proteinases, Cat G has also been shown to bind12 and activate platelets as potently as thrombin.13 Although a specific receptor has not been yet identified for Cat G, it is believed to be different from that of thrombin.14

A functional thrombin receptor expressed by both ECs and platelets has recently been characterized.15,16 This receptor, which is activated by an unusual proteolytic mechanism,15 was the first of the proteinase-activated receptor family to be identified.17,18 It is a 7-transmembrane domain receptor that presents a large extracellular aminoterminal extension containing a cleavage site specific for thrombin, located between residues Arg41 and Ser42. By cleaving this peptide bond, thrombin unmasks a new aminoterminus that functions as a tethered peptide ligand15 that recognizes a sequence located between amino acids Gln83 and Ser93, immediately upstream of the first transmembrane domain,19 and a sequence between amino acids Ile244 and Ala268, in the second extracellular loop.20,21 Recently, Molino et al22 showed that Cat G can suppress activation of ECs and platelets by thrombin through the cleavage of the receptor at the peptide bond between Phe55 and Trp56.

In the present study, we reevaluated the inhibition by Cat G of thrombin-induced cell activation, extended the investigations to the inhibitory activity observed with HLE as well as with PR3, and finally delineated the underlying mechanism of these inhibitions by showing that these proteinases cleave the thrombin receptor at distinct sites within its extracellular aminoterminal domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and reagents.HLE and Cat G were purified from human neutrophils as previously described.23 When required, catalytic sites of HLE and Cat G were blocked by incubating the proteinases with phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF ). PR3 was purified from lysates of leukocyte granules obtained from patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and was a generous gift from Dr J.L. Humes (Merck & Co, Inc, Rahway, NJ). Human thrombin was from Hoffmann-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Histamine, PMSF, PGI2 , EGTA, and the nonimmune monoclonal mouse IgG1 MOPC21 were purchased from Sigma Chemical Corp (St Louis, MO). Fura 2-acetoxymethylester was from Calbiochem Corp (San Diego, CA), and saponin was from Rhône-Poulenc-Rorer (Vitry, France). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from Euromedex (Strasbourg, France). Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and modified Puck's saline A were from GIBCO Life Technology, Ltd (Paisley, UK). Recombinant eglin C was kindly provided by Dr H.P. Schnebli (Ciba-Geigy Research, Basel, Switzerland). D-Phe-L-Pro-L-Arg-CH2Cl was from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp (La Jolla, CA). [125I]-6-keto-PGF1α and anti-6-keto-PGF1α antibodies were from URIA, Institut Pasteur (Paris, France). The murine monoclonal antibody (MoAb) IIaR-A raised against the sequence Lys32-Arg46 of the thrombin receptor was purchased from Valbiotech (Paris, France). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat antibodies to mouse IgG were from Dako A/S (Glostrup, Denmark). The human thrombin receptor-activating peptide, TRAP42-55, was synthesized by Neosystem Laboratoire (Strasbourg, France), as were the four overlapping peptides (purity, ≥95%) corresponding to portions of the aminoterminal domain of the thrombin receptor, ie, TR1 (Asn35-Arg46 ), TR3 (Lys51-Ser64 ), TR4 (Glu60-Asn75 ), and TR5 (Arg70-Pro85 ).

EC cultures.Human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) were isolated and cultured as previously described.8 Monolayers from the first or second subcultures were used in this study.

The immortalized venous human EC (IVEC) line was a gift from Drs P. Vicart and D. Paulin (The Station Centrale de Microscopie Electronique, Institut Pasteur). The line was obtained from HUVECs microinjected with a recombinant DNA fragment composed of a deletion mutant of the human vimentin regulatory region controlling the simian virus-40 early encoding sequence.24 These cells, whose phenotypic markers are conserved when compared with those of primary HUVECs,25 were cultured as previously described.8 Cells between passages 20 to 34 were used in this study.

Preparation of human washed platelets.Platelets were purified by four successive centrifugations of anticoagulated blood obtained from human volunteers. The whole protocol was performed at 37°C as described previously.23 The platelet pellet was eventually resuspended in Tyrode's buffer to obtain a final platelet concentration of 2 × 108 cells/mL.

Determination of PGI2 synthesis.PGI2 was measured from confluent HUVECs washed twice with HBSS supplemented with BSA (0.25%), CaCl2 (1.3 mmol/L), and MgCl2 (1 mmol/L) and was preincubated for 30 minutes at 37°C in the same medium containing increasing concentrations of neutrophil serine proteinases. At the end of this preincubation, the reaction was stopped by addition of eglin C, an inhibitor of neutrophil serine proteinases26,27; the cells were washed, and the stimulation was initiated by addition of various agonists. Thirty minutes later, cell supernatants were collected and centrifuged (300g for 10 minutes), and the aliquots were stored at −20°C until assay. PGI2 synthesis was evaluated as previously described8 by measuring its stable hydrolysis product, ie, 6-keto-PGF1α.

Calcium fluxes measurement.IVECs plated in flasks without gelatin were detached by incubation at 37°C for 30 to 60 minutes with 1.5 mmol/L EDTA. Cells were resuspended in HBSS-BSA and incubated with fura 2-acetoxymethylester (final concentration, 10 μmol/L for 30 minutes at 20°C). After 2 washes, fura 2-loaded IVECs were resuspended in the same medium (106 cells/mL) and kept at 20°C. Immediately before stimulation, IVECs were diluted by half with HBSS-BSA supplemented with CaCl2 and MgCl2. Platelets prepared as described above were incubated with fura 2-acetoxymethylester (final concentration, 3 μmol/L for 45 minutes at 37°C) after the third centrifugation. [Ca2+]i measurements were performed using a spectrofluorimeter (Jobin Yvon JY3D, Paris, France) set at 37°C and under stirring. Calibration for the fura 2 signal was performed by lysing cells with saponin (1 mg/mL) to obtain maximal fluorescence, followed by quenching of the fura 2-associated fluorescence with 30 mmol/L Tris base and 5 mmol/L EGTA to obtain minimal fluorescence. [Ca2+]i was then calculated from the equation given by Grynkiewicz et al,28 using a dissociation constant (kd) of 224 nmol/L.

Flow cytometry analysis.IVECs detached from the flask in the same way as was performed for the determination of calcium fluxes were resuspended (5 × 105 cells/mL) in HBSS-BSA supplemented with CaCl2 and MgCl2 and incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C under stirring in the presence or absence of proteinases. Enzymatic reactions were stopped by addition of eglin C (5 μmol/L), PMSF (1 mmol/L), and ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing BSA (1%) and azide (0.1%). After centrifugation (300g for 10 minutes at 4°C), cells were resuspended at 106 cells/mL, and 100-μL aliquots were incubated (105 cells/incubate) for 30 minutes at 4°C with the MoAb IIaR-A or the control IgG MOPC21 (5 μg/mL). This step was followed by 2 washes with phosphate-buffered saline-BSA-azide and by incubation with an antimouse (30 μg/mL) FITC-conjugated second antibody. After 3 successive washes, cells were fixed with formaldehyde (1% vol/vol) and were analyzed for fluorescence with a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, Mountain View, CA). Washed platelets were incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C in the presence or absence of proteinases in the same manner as was performed for [Ca2+]i measurements but without stirring to avoid aggregation. Enzymatic reactions were stopped, and the labeling of the cells with antibodies was then performed as for ECs at a final platelet count of 2 × 106/incubate. The first incubation with 1 μg/mL of the MoAb IIaR-A or the control IgG was followed by a second incubation with an antimouse (5 μg/mL) FITC-conjugated antibody. Throughout the labeling procedure, platelets were kept in the presence of 1 μmol/L PGI2 , here again to prevent aggregation. Resulting histograms correspond to cell number (y-axis) versus fluorescence intensity (x-axis) plotted on a logarithmic scale.

Peptide cleavage analysis.The site(s) of cleavage by the neutrophil proteinases was searched by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time Of Flight (MALDI-TOF, Bremen, Germany ) mass spectrometry on five overlapping peptides mapping the portion Asn35 to Pro85 of the thrombin receptor, ie, TR1 (Asn35-Arg46 ), TRAP42-55 (Ser42-Phe55 ), TR3 (Lys51-Ser64 ), TR4 (Glu60-Asn75 ), and TR5 (Arg70-Pro85 ). Enzymatic digestion assay was performed at 37°C with HLE, Cat G, or PR3 at the final concentration of 400 nmol/L and with each peptide at 525 μmol/L in 200 mmol/L Tris-acetate (pH, 7.4). After various incubation periods, a 1-μL aliquot was withdrawn from the reaction medium and diluted in 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid, a solution that quenches the enzyme reaction by lowering the pH to ≈3. The stability of the substrates in the absence of proteinases was assessed under the same conditions. The diluted medium was then submitted to MALDI-TOF measurement. Samples were prepared as follows: 1 μL of a saturated 4-α-cyano-4-hydroxy-trans-cinnamic acid solution in acetone was deposited on a stainless-steel probe and allowed to evaporate quickly. Approximately 0.5 μL of the diluted digest solution was then deposited on the matrix surface and allowed to air-dry. At last, the sample was washed according to the method of Vorm and Roepstorff29 with 0.5% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid. Mass spectra were obtained using a Bruker Biflex MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer. The average error on the MALDI-TOF–derived mass is theoritically 0.1%, ie, between 1.4 and 1.8 in our mass range. However, the difference between the experimental mass and the calculated average isotopic mass of our peptides was usually less than 0.5. Therefore, the sequence of the peptide(s) resulting from cleavage by HLE, Cat G, or PR3 could be unambiguously derived from their masses. The instrument was calibrated before each measurement with the monoprotonated molecular ions from a standard mixture of angiotensin II, adrenocorticotropic fragment 18-39 (ACTH 18-39), and bovine insulin. The sequences of the proteolytic fragments were predicted using the MacProMass 1.2 software (Beckman Research Institute, Duarte, CA) on the basis of the known sequence of the initial peptide and the determined molecular masses of the fragment(s).

Statistics.Each data point corresponds to the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments performed in duplicate. Significance was determined by unpaired Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Activation of ECs with thrombin.Intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and PGI2 synthesis induced by increasing concentrations of thrombin were determined from fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension and from HUVEC monolayers, respectively. As shown in Fig 1A, both parameters varied in a concentration-dependent manner and reached a plateau above 1 nmol/L thrombin. This concentration, which raised [Ca2+]i to 371 ± 24 nmol/L (n = 11) and induced synthesis of 11.8 ± 3.6 ng/mL PGI2 (n = 6), was used throughout the next experiments evaluating the inhibitory activities of HLE and Cat G on EC functions.

Activation of ECs by thrombin or TRAP42-55. [Ca2+]i and PGI2 synthesis were measured as detailed in Materials and Methods from fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension and from confluent HUVEC monolayers, respectively, stimulated with increasing concentrations of either thrombin (A) or TRAP42-55 (B). Each point is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.

Activation of ECs by thrombin or TRAP42-55. [Ca2+]i and PGI2 synthesis were measured as detailed in Materials and Methods from fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension and from confluent HUVEC monolayers, respectively, stimulated with increasing concentrations of either thrombin (A) or TRAP42-55 (B). Each point is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.

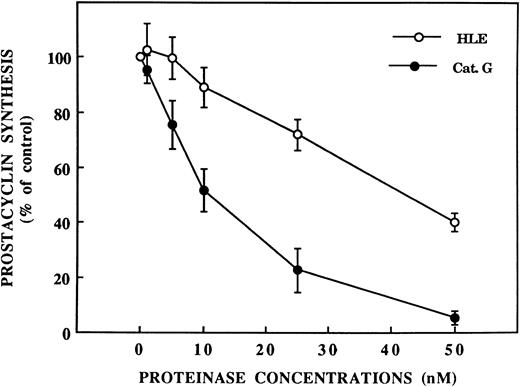

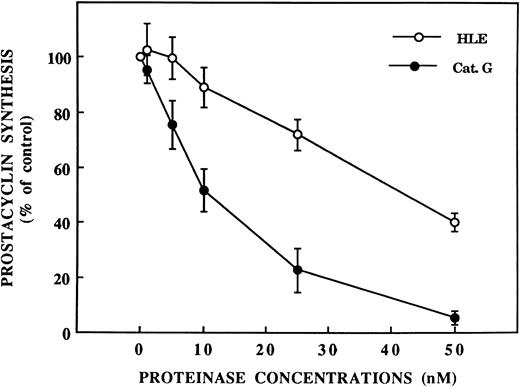

Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of thrombin-induced EC activation.As shown in Fig 2, preincubation of IVECs for 5 minutes with HLE or Cat G resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of the [Ca2+]i increase when cells were subsequently activated with thrombin. Thus, in ECs pretreated with HLE or Cat G at 400 nmol/L, the responses to 1 nmol/L thrombin were inhibited by 86.9% ± 5.9% (n = 4) or 83.5% ± 12.1% (n = 3), respectively. This phenomenon was also dependent on the preincubation time of ECs with the proteinases. Thus, incubation of IVECs with 400 nmol/L HLE or Cat G for 2.5 minutes resulted in a partial inhibition of ≈65%. PGI2 synthesis induced by thombin in HUVECs was also sensitive to the neutrophil proteinases. As shown in Fig 3, preincubation of ECs for 30 minutes with 50 nmol/L HLE or Cat G resulted in a 59.7% ± 3.5% (n = 5) and 94.9% ± 2.4% (n = 5) decrease in PGI2 production, respectively. Higher concentrations of neutrophil proteinases were not tested to avoid cell detachment. The observed inhibitions were related to the enzymatic activity of the proteinases, because PMSF-inactivated HLE and Cat G failed to affect EC responses to thrombin, both in terms of [Ca2+]i increase and PGI2 synthesis (data not shown). It is of note that, by themselves, Cat G and HLE at concentrations to 400 nmol/L did not triggered either [Ca2+]i variations or PGI2 synthesis under our different experimental conditions.

Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of Ca2+ mobilization induced by thrombin in ECs. [Ca2+]i was measured from fura 2-loaded IVECs preincubated for 5 minutes with increasing concentrations of HLE or Cat G before cell stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin. [Ca2+]i are expressed as the percentage of values measured on nontreated cells stimulated by thrombin. Basal [Ca2+]i was 177 ± 12 nmol/L (n = 7), and each histogram is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.

Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of Ca2+ mobilization induced by thrombin in ECs. [Ca2+]i was measured from fura 2-loaded IVECs preincubated for 5 minutes with increasing concentrations of HLE or Cat G before cell stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin. [Ca2+]i are expressed as the percentage of values measured on nontreated cells stimulated by thrombin. Basal [Ca2+]i was 177 ± 12 nmol/L (n = 7), and each histogram is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.

Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of PGI2 synthesis induced by thrombin in ECs. PGI2 synthesis was measured from supernatants of confluent HUVEC monolayers preincubated for 30 minutes with increasing concentrations of HLE or Cat G before stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin. Each data point is expressed as the percentage of PGI2 synthesis measured from control, nonpretreated cells activated by thrombin and corresponds to the mean ± SEM of four to five distinct experiments.

Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of PGI2 synthesis induced by thrombin in ECs. PGI2 synthesis was measured from supernatants of confluent HUVEC monolayers preincubated for 30 minutes with increasing concentrations of HLE or Cat G before stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin. Each data point is expressed as the percentage of PGI2 synthesis measured from control, nonpretreated cells activated by thrombin and corresponds to the mean ± SEM of four to five distinct experiments.

Specificity of the inhibition induced by HLE and Cat G on ECs.Although HLE and Cat G strongly inhibited the activation of ECs induced by thrombin, both proteinases failed to impair cell responses when histamine was the agonist. These experiments were performed with 0.1 mmol/L histamine, ie, a concentration that induced [Ca2+]i increase and PGI2 synthesis with the same magnitude as those obtained with 1 nmol/L thrombin (data not shown). The specificity of the inhibition was further evidenced by the use of the synthetic peptide TRAP42-55, which activated ECs in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig 1B). At the concentration of 12.5 μmol/L, this agonist triggered a [Ca2+]i increase (430 ± 40 nmol/L; n = 4) and PGI2 synthesis (11.9 ± 3.5 ng/mL; n = 6) that were comparable with those induced by 1 nmol/L thrombin. However, preincubation of ECs with HLE or Cat G, under conditions for which thrombin responses were highly reduced, failed to affect [Ca2+]i increase (Fig 4A) and PGI2 synthesis (Fig 4B) induced by 12.5 μmol/L TRAP42-55.

Effect of HLE and Cat G on EC activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. (A) [Ca2+]i was determined in fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension preincubated for 5 minutes with 600 nmol/L Cat G or HLE before stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin () or 12.5 μmol/L TRAP42-55 (▨). (B) PGI2 synthesis was measured from supernatants of confluent HUVEC monolayers preincubated for 30 minutes with 50 nmol/L HLE or Cat G before stimulation with a similar concentration of the same agonists. Data are expressed as the percentage of the control values (no preincubation with HLE or Cat G). Each histogram is the mean ± SEM of three to four distinct experiments.

Effect of HLE and Cat G on EC activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. (A) [Ca2+]i was determined in fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension preincubated for 5 minutes with 600 nmol/L Cat G or HLE before stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin () or 12.5 μmol/L TRAP42-55 (▨). (B) PGI2 synthesis was measured from supernatants of confluent HUVEC monolayers preincubated for 30 minutes with 50 nmol/L HLE or Cat G before stimulation with a similar concentration of the same agonists. Data are expressed as the percentage of the control values (no preincubation with HLE or Cat G). Each histogram is the mean ± SEM of three to four distinct experiments.

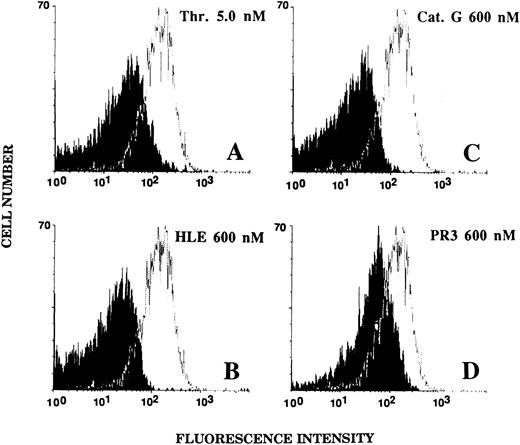

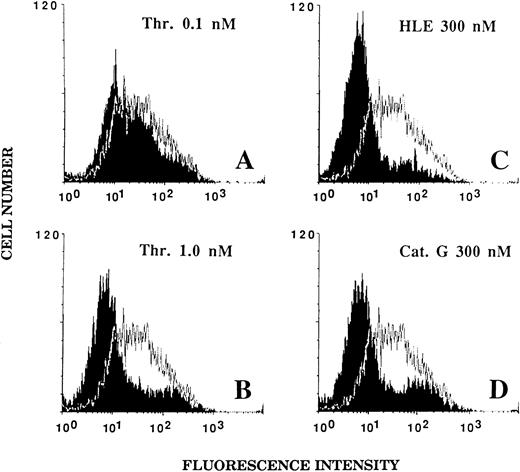

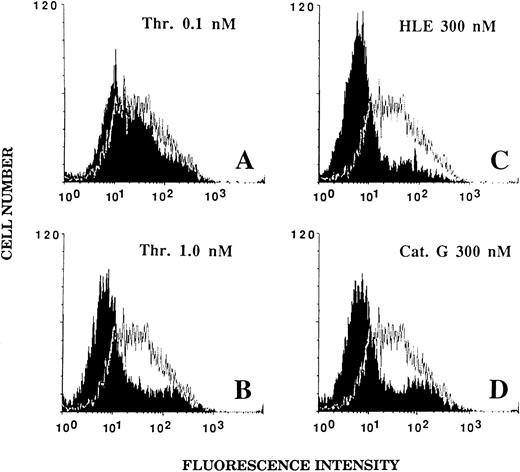

Effect of HLE and Cat G on the expression of the thrombin receptor at the surface of ECs.An alteration of the thrombin receptor by neutrophil serine proteinases suggested by the above data was shown by flow cytometry analysis coupled with the use of an MoAb, IIaR-A, directed at the sequence Lys32-Arg46 encompassing the thrombin cleavage site.15 It was first verified that, when compared with a nonimmune control IgG1 , IIaR-A specifically labeled the thrombin receptor. Indeed, the mean values of median fluorescence intensity (MFI) were 22.2 ± 2.7 for IIaR-A versus 10.7 ± 1.1 for the control IgG (P < .05; n = 3). As shown in Fig 5A, exposure of ECs for 5 minutes to 0.1 nmol/L thrombin, a concentration inducing no significant cell activation (see Fig 1A), only produced a slight left shift of the fluorescence intensity (MFI, 17.5 ± 2.5; n = 3). By contrast, when ECs were exposed to an optimal thrombin concentration (ie, 1 nmol/L), the fluorescence signal given by IIaR-A was reduced to that measured with the control antibody (MFI, 7.3 ± 0.3; n = 3; see Fig 5B). Similarly, when ECs were incubated for 5 minutes with either 300 nmol/L HLE or Cat G (Fig 5C and 5D), the expression of the epitope encompassing the cleavage site for thrombin was no more detectable (MFI, 7.2 ± 0.5 and 7.9 ± 0.6, respectively; n = 3).

Effect of thrombin, HLE, and Cat G on the expression of the thrombin receptor at the surface of ECs. IVECs in suspension were incubated for 5 minutes with thrombin (A and B), HLE (C), or Cat G (D) at the indicated concentrations and were then reacted with the murine antithrombin receptor MoAb IIaR-A, followed by FITC-conjugated antimouse IgG, as detailed in Materials and Methods. For each experimental condition, the observed tracing (in black) is shown for comparison with a typical tracing (superimposed) representative of the control condition (ie, without pretreatment with any of the proteinases). The MFI value for the control irrelevant monoclonal IgG was 10.7 ± 1.1 (n = 3). Tracings are representative of four distinct experiments.

Effect of thrombin, HLE, and Cat G on the expression of the thrombin receptor at the surface of ECs. IVECs in suspension were incubated for 5 minutes with thrombin (A and B), HLE (C), or Cat G (D) at the indicated concentrations and were then reacted with the murine antithrombin receptor MoAb IIaR-A, followed by FITC-conjugated antimouse IgG, as detailed in Materials and Methods. For each experimental condition, the observed tracing (in black) is shown for comparison with a typical tracing (superimposed) representative of the control condition (ie, without pretreatment with any of the proteinases). The MFI value for the control irrelevant monoclonal IgG was 10.7 ± 1.1 (n = 3). Tracings are representative of four distinct experiments.

Effect of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on platelet activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55.The above observations were extended to another cell expressing the same functional 7-transmembrane domain thrombin receptor. Thus, experiments were conducted with human platelets, a typical cell type activated by thrombin (see Fig 6A).10 The [Ca2+]i increase induced by an optimal concentration of this agonist (5 nmol/L) was measured after preincubation of platelets for 5 minutes with 600 nmol/L HLE or Cat G or with the same concentration of PR3 (the latter neutrophil proteinase was tested on platelets rather than on ECs because of its scarcity). As shown in Fig 6B, the [Ca2+]i increase triggered by thrombin was completely suppressed after preincubation with HLE. However, a subsequent addition of 6.25 μmol/L TRAP42-55 resulted in a strong intracellular Ca2+ mobilization. Because Cat G triggers a Ca2+ flux by itself (Fig 6C), thus preventing a further challenge of platelets by thrombin within 5 minutes, the latter was added when the [Ca2+]i had returned to near its basal value. Under these conditions, thrombin was unable to mobilize cytosolic Ca2+ while TRAP42-55 was still effective. Finally, preincubation of platelets with PR3 resulted in an inhibition, although incomplete, of the response to thrombin (Fig 6D). Here again, subsequent addition of TRAP42-55 induced a signal comparable with that observed after preincubation with Cat G. Of note is that TRAP42-55–induced [Ca2+]i increases were less marked in platelets preincubated with Cat G or PR3, most likely because of the first Ca2+ mobilization initiated by Cat G or thrombin, respectively (Fig 6C and 6D). Under these conditions, Ca2+ stores are possibly partially desensitized and/or incompletely replenished at the time of TRAP42-55 addition. Experiments were also conducted with compound U-46619, a prostaglandin endoperoxide analog that is another platelet agonist signaling through a 7-transmembrane domain receptor.30 As opposed to thrombin, compound U-46619, at the suboptimal concentration of 0.1 μmol/L (a concentration less effective than 5 nmol/L thrombin in terms of calcium mobilization), triggered comparable [Ca2+]i increases whether or not platelets were preincubated with HLE (data not shown).

Effect of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on platelet activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. Stirred fura 2-loaded platelets were preincubated with buffer (A) or 600 nmol/L of each of the neutrophil proteinases (B to D). The preincubation time was 5 minutes except for Cat G (C), for which a longer period was required to allow the Ca2+ mobilization induced by this proteinase to return to the basal value. After stimulation of platelets with 5 nmol/L thrombin, platelets were further challenged with 6.25 μmol/L TRAP42-55. Changes in fluorescence intensity reflect changes in [Ca2+]i and are representative of three distinct experiments.

Effect of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on platelet activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. Stirred fura 2-loaded platelets were preincubated with buffer (A) or 600 nmol/L of each of the neutrophil proteinases (B to D). The preincubation time was 5 minutes except for Cat G (C), for which a longer period was required to allow the Ca2+ mobilization induced by this proteinase to return to the basal value. After stimulation of platelets with 5 nmol/L thrombin, platelets were further challenged with 6.25 μmol/L TRAP42-55. Changes in fluorescence intensity reflect changes in [Ca2+]i and are representative of three distinct experiments.

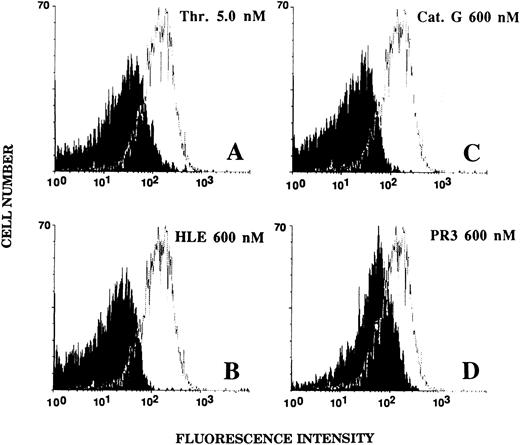

Effect of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on the expression of the thrombin receptor on the surface of platelets.The integrity of the extracellular aminoterminal domain of the thrombin receptor on the surface of platelets was examined by flow cytometry analysis under the conditions described for ECs. Untreated platelets showed a strong labeling with the IIaR-A antibody, as judged from an MFI value of 144.1 ± 37.5 (n = 10) for the IIaR-A antibody as compared with that of 15.2 ± 2.1 (n = 10) for the control MoAb. As shown in Fig 7, platelets exposed for 5 minutes to 600 nmol/L HLE (Fig 7B) or Cat G (Fig 7C) no longer showed expression of the targeted epitope (MFI, 19.8 ± 3.9 and 19.6 ± 3.8, respectively; n = 3). For comparison, platelets were also treated with 5 nmol/L thrombin (Fig 7A), and, as expected, the expression of the epitope recognized by IIaR-A was also suppressed (MFI, 22.1 ± 4.8; n = 6). When platelets were treated with PR3 under the same experimental conditions (Fig 7D), a partial inhibition (≈55%) of the binding of the antibody was shown, with an MFI of 73.4 ± 23.9 (n = 3).

Effects of thrombin, HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on the expression of the thrombin receptor at the surface of platelets. Unstirred platelets were incubated for 5 minutes with thrombin (A) or the neutrophil proteinases (B to D) as described in the legend to Fig 6. Binding of the IIaR-A antibody was measured by flow cytometry as detailed in the legend to Fig 5. For each experimental condition, the observed tracing (in black) is shown for comparison with a typical tracing (superimposed) representative of the control condition (ie, without pretreatment with any of the proteinases). The MFI value for the control irrelevant monoclonal IgG was 15.2 ± 2.1 (n = 10). Tracings are representative of at least three distinct experiments.

Effects of thrombin, HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on the expression of the thrombin receptor at the surface of platelets. Unstirred platelets were incubated for 5 minutes with thrombin (A) or the neutrophil proteinases (B to D) as described in the legend to Fig 6. Binding of the IIaR-A antibody was measured by flow cytometry as detailed in the legend to Fig 5. For each experimental condition, the observed tracing (in black) is shown for comparison with a typical tracing (superimposed) representative of the control condition (ie, without pretreatment with any of the proteinases). The MFI value for the control irrelevant monoclonal IgG was 15.2 ± 2.1 (n = 10). Tracings are representative of at least three distinct experiments.

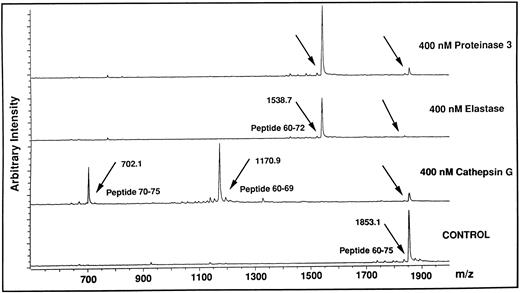

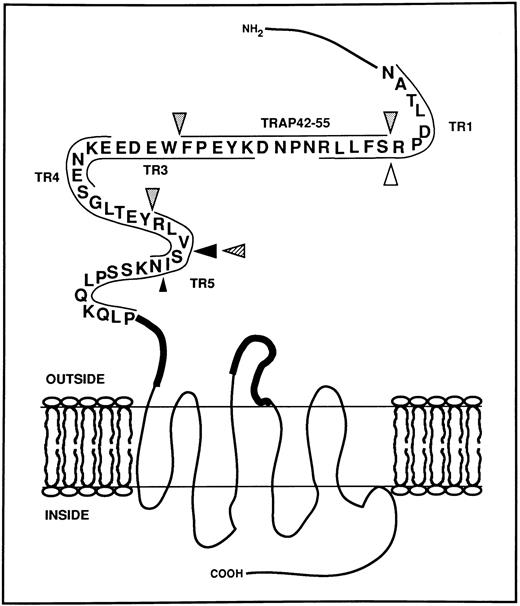

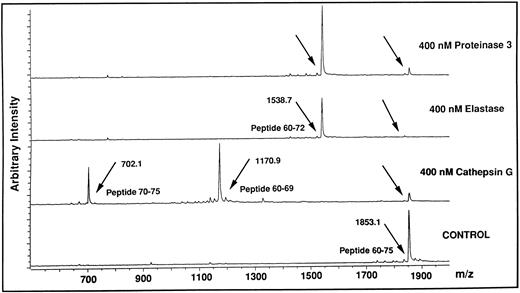

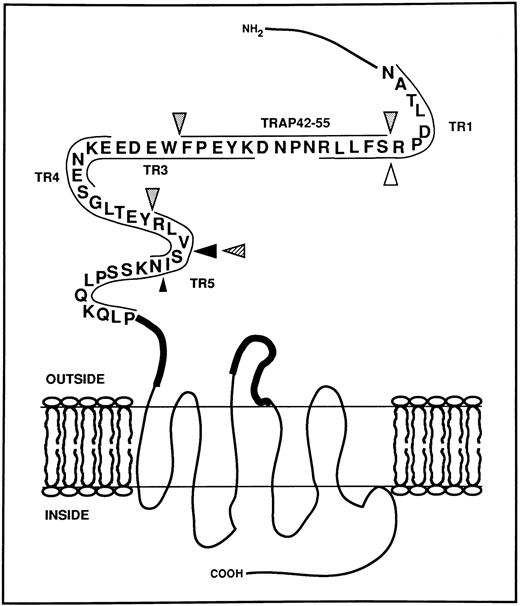

Identification of cleavage sites for HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on the aminoterminal extracellular domain of the thrombin receptor.Based on the findings obtained with thrombin and TRAP42-55 in functional studies compared with those obtained with flow cytometry analysis using the IIaR-A antibody, it can be assumed that the neutrophil proteinases cleave the thrombin receptor within its extracellular aminoterminal domain in a region located downstream of Ser42 and upstream of Gln83. To identify potential cleavage sites within this stretch of amino acids, each of the proteinases were incubated with each of five overlapping peptides encompassing this domain of the thrombin receptor, ie, TR1 (Asn35-Arg46 ), TRAP42-55 (Ser42-Phe55 ), TR3 (Lys51-Ser64 ), TR4 (Glu60-Asn75 ), and TR5 (Arg70-Pro85 ). The reaction mixtures were subjected at different time intervals to MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to identify the generated peptides. For example, Fig 8 shows the reaction of TR4 for 10 minutes with HLE, Cat G, or PR3. In the presence of Cat G, the TR4 peptide with a molecular mass of 1853.1 (Fig 8, lower tracing) produced two peptides with molecular masses of 1170.9 and 702.1. This result allowed us to deduce that Cat G cleaves between Tyr69 and Arg70, a cleavage not previously described. When HLE or PR3 were incubated with the same peptide, a common cleavage site was detected at Val72-Ser73 (Fig 8, the two upper tracings). Under these experimental conditions, the resulting Glu60-Val72 peptide could be shown, but the complementary tripeptide Ser73-Asn75 could not. Of note is that all these cleavages were actually observed within 1 minute of reaction. When incubations were conducted for longer periods of time, up to 30 minutes, no other proteolytic sites were observed on TR4. A second cleavage site was detected for HLE at Ile74-Asn75, but only on TR5 and for incubations above 30 minutes. To summarize the data, treatments of the five peptides with the three proteinases for different times of incubation allowed for the determination of distinct specific cleavage points, ie, Val72-Ser73 and Ile74-Asn75 for HLE, Val72-Ser73 for PR3, and the two sites Arg41-Ser42 and Phe55-Trp56 previously reported for Cat G,22 together with an as yet unidentified one between Tyr69 and Arg70. These different sites are shown on a schematic representation of the aminoterminal domain of the thrombin receptor (Fig 9), with arrows drawn according to the kinetics of each enzymatic reaction (ie, large arrows for cleavages rapidly observed, and a small arrow for the cleavage observed beyond 30 minutes). It is noteworthy that thrombin cleaved TR1 at Arg41-Ser42 and cleaved only this peptide.

Analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of the cleavage of the TR4 peptide by HLE, Cat G, and PR3. The lower tracing (Control) is the mass spectrum of the untreated TR4 peptide corresponding to the Glu60-Asn75 domain of the thrombin receptor (m/z, observed mass charge = 1853.1). The three upper tracings are mass spectra of the peptides obtained after a 10-minute digestion with each of the neutrophil proteinases (arrows). Tracings are representative of two distinct experiments.

Analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of the cleavage of the TR4 peptide by HLE, Cat G, and PR3. The lower tracing (Control) is the mass spectrum of the untreated TR4 peptide corresponding to the Glu60-Asn75 domain of the thrombin receptor (m/z, observed mass charge = 1853.1). The three upper tracings are mass spectra of the peptides obtained after a 10-minute digestion with each of the neutrophil proteinases (arrows). Tracings are representative of two distinct experiments.

Schematic representation of the extracellular aminoterminal domain of the thrombin receptor with the potential cleavage sites generated by HLE, Cat G, and PR3. The sequence of the thrombin receptor located between Asn35 and Pro85 is represented using the single-letter code for amino acids.15 Synthetic peptides used in this study and mapping over this domain are located by thin lines. Bold lines represent the putative sequences Gln83-Ser93 and Ile244-Ala268 involved in the binding of the tethered ligand.19-21 Large arrowheads indicate cleavage sites observed as soon as 1 minute of proteolysis in MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry studies, whereas the small arrowhead shows a cleavage detected after 30 minutes (Cat G, ; HLE, ▴; PR3, ). The white arrowhead (▵) indicates the cleavage site determined for thrombin.15

Schematic representation of the extracellular aminoterminal domain of the thrombin receptor with the potential cleavage sites generated by HLE, Cat G, and PR3. The sequence of the thrombin receptor located between Asn35 and Pro85 is represented using the single-letter code for amino acids.15 Synthetic peptides used in this study and mapping over this domain are located by thin lines. Bold lines represent the putative sequences Gln83-Ser93 and Ile244-Ala268 involved in the binding of the tethered ligand.19-21 Large arrowheads indicate cleavage sites observed as soon as 1 minute of proteolysis in MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry studies, whereas the small arrowhead shows a cleavage detected after 30 minutes (Cat G, ; HLE, ▴; PR3, ). The white arrowhead (▵) indicates the cleavage site determined for thrombin.15

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to assess by which mechanism(s) secretable serine proteinases stored in the azurophilic granules of neutrophils inhibit thrombin-induced cell activation, a phenomenon initially reported by Weksler et al9 for HLE- or Cat G-treated ECs. We now bring new evidence that the 7-transmembrane domain thrombin receptor expressed at the surface of ECs and platelets is specifically proteolyzed by these neutrophil proteinases, including the more recently characterized PR3.

After the determination of the concentration of thrombin necessary to trigger an optimal activation of ECs, as measured by the [Ca2+]i increase in IVECs or PGI2 synthesis in HUVECs, we evaluated the effects of the neutrophil proteinases on this activation. The initial data obtained with HLE were consistent with those previously reported,9 in that 400 nmol/L inhibited by 85% the [Ca2+]i increase induced by 1 nmol/L thrombin. The inhibitory effect was dependent not only on the proteinase concentration, but also on the preincubation time of ECs with HLE. Similar data were obtained with Cat G. Because the neutrophil proteinases were neutralized by addition of eglin C and removed by washings before stimulation with thrombin, a proteolytic alteration of the latter, which can be exerted by HLE31 or Cat G,32 could not be responsible for the inhibitory phenomenon. Nonetheless, a proteolytic mechanism was actually involved in the inhibition of EC activation, because HLE and Cat G failed to modify the cell responses to thrombin when their catalytic sites were blocked. Our data bear some analogies with those reported by Hartman et al33 concerning the specific inhibitory effect of tryptase, a serine proteinase close to HLE and Cat G, on vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated with thrombin.

That neutrophil serine proteinases altered a thrombin-specific, cell surface-restricted process was evidenced by two sets of data. First, when ECs were preincubated with concentrations of HLE or Cat G inhibiting the thrombin response, the cell reactivity to histamine was not modified. Second, EC activation triggered by the synthetic peptide TRAP42-55, which mimics the effects of the thrombin receptor tethered ligand,15 was not modified by HLE or Cat G. These results clearly show that the intracellular signaling pathway involved in thrombin-induced activation is not directly affected by the neutrophil proteinases and favor a proteolytic mechanism directed at the 7-transmembrane domain thrombin receptor. Nonetheless, this inference could have been inappropriate because the synthetic peptide is likely to activate the so-called proteinase-activated receptor-2,34 another 7-transmembrane domain receptor related to the thrombin receptor and known to be expressed at the surface of ECs.35 With the aim to reinforce our assumption, we considered another cell type, ie, platelets, known to bear on their surface the very same thrombin receptor36 and not proteinase-activated receptor-2.34 A similar pattern of data was obtained when measuring [Ca2+]i increases. Thus, preincubation of platelets with HLE or Cat G fully inhibited their response to thrombin, while they remained responsive to TRAP42-55. The third proteinase stored in the azurophilic granules of the neutrophils was also tested under similar conditions. Although less potent than HLE and Cat G, PR3 also was able to reduce the activation of platelets induced by thrombin while not affecting the response to TRAP42-55.

At this stage, we could conclude that the neutrophil enzymes effectively interfered with the thrombin receptor. However, there are emerging data suggesting the presence of a second mechanism for thrombin-induced platelet activation.37 Nonetheless, if the presence of a second putative receptor is quite obvious for murine platelets, this appears not the case for human platelets.37 Indeed, an antibody raised against the whole aminoterminal extracellular domain of the cloned receptor severely inhibited activation of human platelets by thrombin.20 A further series of experiments allowed us to definitely show that the mechanism responsible for the inhibition of thrombin-induced cell activation pertains to a structural modification of the characterized thrombin receptor itself. This conclusion was established from flow cytometry experiments using the MoAb IIaR-A, which recognizes the sequence Lys32-Arg46 of the receptor encompassing the thrombin cleavage site Arg41-Ser42.15 Our results indicated that the binding of this antibody decreased when ECs or platelets were preincubated with one of the three neutrophil proteinases. This effect, which is consistent with recent data obtained with HLE on platelets,38 might result from either the cleavage or the internalization of the receptor, two events likely to occur after its interaction with thrombin.11 In fact, because in our study the pretreatment of ECs and platelets with HLE, Cat G, or PR3 failed to prevent their reactivity to TRAP42-55, which activates cells by notably recognizing a sequence located between Gln83 and Ser93,19 an internalization and/or a desensitization of the receptor induced by these proteinases could be reasonably ruled out. Moreover, as far as platelets are concerned, Norton et al39 have previously shown the absence of internalization of the receptor after its cleavage by thrombin. Data obtained with TRAP42-55 and the antibody IIaR-A, together with the need for neutrophil proteinases to be enzymatically active, led us to search for cleavages within the aminoterminal extension of the receptor located between Ser42 and Gln83. Such cleavages would thus explain both the inhibition of cell responses to thrombin and the unaffected responses to TRAP42-55. To pinpoint which peptide bonds are cleaved by the different proteinases within this extracellular domain, five different overlapping peptides encompassing the stretch of amino acids between Asn35 and Pro85 were synthesized and reacted with each neutrophil proteinase. Sites of cleavage were then located by mass spectrometric analysis of the generated fragments. The rationale for the overlaps and the extension beyond the critical ends (Ser42 and Gln83 ) was that, for a proteinase such as HLE, the substrate binding site extends from 4 amino acids toward the aminoterminus (P1 to P4) to 3 amino acids toward the carboxyterminus (P′1 to P′3).40 This was verified with HLE for the cleavage of the peptide bond Ile74-Asn75, which was apparent with the TR5 peptide (Arg70-Pro85 ), but not with the TR4 peptide (Glu60-Asn75 ). From these experiments, we describe for the first time two cleavage sites for HLE, a very late one (Ile74-Asn75 ) and another shared with PR3, ie, Val72-Ser73. This latter cleavage can alone account for the ability of HLE to inhibit cell responses to thrombin, considering that it appears as early as 1 minute. Similarly, this cleavage can also explain the inhibitory effect of PR3, although, when tested on cells bearing the thrombin receptor, this proteinase is less potent than HLE in terms of disappearance of the thrombin cleavage site and of inhibition of thrombin-induced [Ca2+]i increase. At present, we do not have an explanation for this discrepancy. As for Cat G, we confirm previous findings identifying two proteolytic sites after Arg41 and Phe55.22 Moreover, we also report on an as yet undescribed third cleavage site for Cat G at Tyr69-Arg70. This latter cleavage and that after Phe55 would both participate in the inhibition of thrombin-induced cell activation. Further experiments will be needed to evaluate the occurrence of these cleavages in the thrombin receptor in situ and that of those reported for HLE and PR3. Actually, we attempted to characterize the membrane-bound fragments of the thrombin receptor generated on the surface of platelets exposed to thrombin or each of the three neutrophil proteinases. For this, we immunoblotted proteins from platelet lysates with a series of MoAbs or polyclonal antibodies directed at various epitopes within the extracellular aminoterminal domain of the receptor. Unfortunately, none of these antibodies allowed for a reproducible and unambiguous detection of the intact receptor, and no fragment could be visualized through this procedure (data not shown). Regardless, it must be noticed that the observed proteolysis after Val by HLE and PR3, on the one hand, and after Phe or Trp by Cat G, on the other hand, are in agreement with their primary amino acid residue specificity.41,42 Finally, the high susceptibility of the thrombin receptor to proteolysis by the neutrophil enzymes appears to be unique. Hence, two other unrelated 7-transmembrane domain receptors, one for histamine on ECs43 and one for prostaglandin endoperoxides on platelets,30 were not affected by these proteinases.

In conclusion, the ability of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 to downregulate the activity of the thrombin receptor on ECs and platelets provides a new pathway by which leukocytes can modulate the hemostatic balance and the inflammatory process. This may even be extended to tissue remodeling and wound repair, because thrombin is known as a mitogenic factor inducing proliferation of ECs, vascular smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts.44 In support of this proposal, it has been shown recently that (1) serine proteinases are readily expressed at the surface of neutrophils on their activation by inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-α and, more importantly, (2) these bound proteinases are active and are hardly inhibited by the specific natural antiproteinase screen afforded by plasma.45-47

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr J. L. Humes for his kind gift of purified PR3 and Drs P. Vicart and D. Paulin for the gift of the IVEC line used in this study.

Supported in part by the Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche (action “Cellules des parois vasculaires”). D.P. is supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (France), M.S.-T. by a fellowship from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (Villejuif, France), and M.M. and A.V.D. by BioAvenir (Rhône-Poulenc Santé, France).

Address reprint requests to Michel Chignard, PhD, Unité de Pharmacologie Cellulaire, Unité associée IP/INSERM 285, Institut Pasteur, 25, rue du Dr Roux, 75015 Paris, France.

![Fig. 1. Activation of ECs by thrombin or TRAP42-55. [Ca2+]i and PGI2 synthesis were measured as detailed in Materials and Methods from fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension and from confluent HUVEC monolayers, respectively, stimulated with increasing concentrations of either thrombin (A) or TRAP42-55 (B). Each point is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f1.jpeg?Expires=1769290762&Signature=AXcrkYU9ANSOxCIiRb86MYjdCrJ1trbs851DSIDoM5WPlLazeG8dL8Chg9XMnGEGNTWCg8XO3l6VIsJf-4LJvbqQskqET9d9BUb394X5L899qhvJn8N0HH3ow6sjawK0DUEExfdWhiyYqDRxFXHThq8Sx~-YSLBPbMN-BZ8LPWmldBZaGR1FU6apal0yRyoSy46CHJxiapFyjeMmRbVsMGEwgktHsUS8rvWziTMT0lF9xeOHWuSj7CLqiRDQ-NJJSQbihqjjVPe9eQ7FJRkkt7r32YzOlCJ5WkWqb~2ExcRGBXhlD96jLgfMIdP0W7W-vGcIH7MA2~lkcOjU5IvTJg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of Ca2+ mobilization induced by thrombin in ECs. [Ca2+]i was measured from fura 2-loaded IVECs preincubated for 5 minutes with increasing concentrations of HLE or Cat G before cell stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin. [Ca2+]i are expressed as the percentage of values measured on nontreated cells stimulated by thrombin. Basal [Ca2+]i was 177 ± 12 nmol/L (n = 7), and each histogram is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f2.jpeg?Expires=1769290762&Signature=2mlz2KHw-kqYnItZgRfMgd1-wB7D~7mBkTbNQC-tM7-8zE2xY3A6Nw34-mqpRCeuojKJU~65hmLmF8X1qGvwxgYPNNT8rjihqTGaXb4TP3HI~kcW~CXJsz4NPuttKHaYzWdbjtCtOk-AbyPuidmIGZUhFoHsc8m3l3IIbBqDqzq3tVPXOKAhArtvWb6nTRDlFaGqe9-4-tmHyz69gjjneVXVS9LI7ULJULN5YGH-qWS-ygPgfMjsZAko99g16YFVQQVaykq7mNh-zi05dPyN88TnMYXbyZThjzh5PAWgv4SeGaZ2YTRIxCFwOLcvsE1EkRVSrJIK4D~JcTdwG1BZ7A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Effect of HLE and Cat G on EC activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. (A) [Ca2+]i was determined in fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension preincubated for 5 minutes with 600 nmol/L Cat G or HLE before stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin () or 12.5 μmol/L TRAP42-55 (▨). (B) PGI2 synthesis was measured from supernatants of confluent HUVEC monolayers preincubated for 30 minutes with 50 nmol/L HLE or Cat G before stimulation with a similar concentration of the same agonists. Data are expressed as the percentage of the control values (no preincubation with HLE or Cat G). Each histogram is the mean ± SEM of three to four distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f4.jpeg?Expires=1769290762&Signature=O1KbVZsm-PUDgGMcs2Si154cbjeLbMW8JJq6KLQW4mEGuamn4uNNYuMBV7GKDnUnV3w8OvyXoB-tMwTvqoD-0MZMTeJgXS8~zgAID63BQGDCYw2mutBoPC0f14p95T6U9lsczW-Y36uRbsGih50aluxc2uhvY8k8Kio~zmCiFaIA~EAcMNSNHP3p0-Qs9OEzapb-tt7-uqrlsCp6hGzCskAHjYGHs~zj2zDAxdFarWZA5l~NuegvZLVfVFdqxznIU60siSotW5nkYHKLXDgRQLjCHZ6-HWZmpMGKc2ES43X5pPUMm~8lW53oU79wP11LkJPMP165y5oE7cQdqHRMZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. Effect of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on platelet activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. Stirred fura 2-loaded platelets were preincubated with buffer (A) or 600 nmol/L of each of the neutrophil proteinases (B to D). The preincubation time was 5 minutes except for Cat G (C), for which a longer period was required to allow the Ca2+ mobilization induced by this proteinase to return to the basal value. After stimulation of platelets with 5 nmol/L thrombin, platelets were further challenged with 6.25 μmol/L TRAP42-55. Changes in fluorescence intensity reflect changes in [Ca2+]i and are representative of three distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f6.jpeg?Expires=1769290762&Signature=U55RlNHnYUOuDRQPY1hVMovEqkDbe3eXB1Oy3VdBZp~7KJRC3b7hCGzLt0keGm-dQ-vS3P44Jli9P0xOtBT3KeR3Bty1ET-lzMod0FyEmmtRznr4IwW8R~Q6459jw~7BE~A7ry15CyAatNtMHtEhOb3V1vM2LPv3ySgbDMBsPxi1CAqegP~X1TO-pAOGO05M4BUdW9UVQ8xBU~94~PSW4rkwZocPpfcfS4VuYPhTLUNVWA6jLmFrvDIvuybaN8MdD46U5dF5kTMZejvd-J1LOwD1gFzjH8pE6xZZKZhL0utH~gyaSd786BRh1XZipshWrT0j1CHsAAvwZ3I9dWa~ew__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 1. Activation of ECs by thrombin or TRAP42-55. [Ca2+]i and PGI2 synthesis were measured as detailed in Materials and Methods from fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension and from confluent HUVEC monolayers, respectively, stimulated with increasing concentrations of either thrombin (A) or TRAP42-55 (B). Each point is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f1.jpeg?Expires=1769364233&Signature=kmXsnErwa~8c3ifUThIUas7tbsbgqlmBadZ9IMdTrwesr8UtamAd5qxWiQTag8er~-IKqxcbQoF6iINC-DTD-62C~ilPCvbF326Rv9uxioiS0Tw6sVl8hPbsuJihgi8nGE1~vFpOuPbxGu8Fb29Nv3vQIdnQfdVBbCponQ5xypDKHX0PhC-fniDWrpxRijIGdsKGSIhfaJEfEvszyNh9IHk3Qee2jNF5xD47g5BCi3giweKpAyPYK~TnmYNQkbcBasatdLI6MJmrecQ55NZxBtu9ZbyJk~ZoCAalV14B9qxZtqODkBbsuIXjpOMPYBG5AfhZGrXbROU9kvYv~FCReQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 2. Inhibition by HLE and Cat G of Ca2+ mobilization induced by thrombin in ECs. [Ca2+]i was measured from fura 2-loaded IVECs preincubated for 5 minutes with increasing concentrations of HLE or Cat G before cell stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin. [Ca2+]i are expressed as the percentage of values measured on nontreated cells stimulated by thrombin. Basal [Ca2+]i was 177 ± 12 nmol/L (n = 7), and each histogram is the mean ± SEM of at least three distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f2.jpeg?Expires=1769364233&Signature=DZYcHmc4oYSmnViTqLWmpS~DCtJFelKbUSeTBDqD-eCUYy6TVG-dURaFu7fQKJ-wQpBhUjyxmreQotfyLcL-BCsIM-6j6IJMN~4iu14NxFoV0yK0ItYorbh3VPIRo3dInqvj-X6SUq44nRSGmrLoHpIeY07mSx7raHoZ5TwlFVvRxKJlwkmPJE-guTaEMrpmciedIrK8NqcPPjOw038ifIS47q446cQwDRO1uJ4pHUskYqR3fjqOTmjhLmy90Ac6PMh98omuq-zGtRp3G7xwZXmVhxkOSO23MjtsT9VJ5ay~03m8yPKPYG2ZE9MceUd7guXOPeVBFkQv9oaUNRHt7g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Effect of HLE and Cat G on EC activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. (A) [Ca2+]i was determined in fura 2-loaded IVECs in suspension preincubated for 5 minutes with 600 nmol/L Cat G or HLE before stimulation with 1 nmol/L thrombin () or 12.5 μmol/L TRAP42-55 (▨). (B) PGI2 synthesis was measured from supernatants of confluent HUVEC monolayers preincubated for 30 minutes with 50 nmol/L HLE or Cat G before stimulation with a similar concentration of the same agonists. Data are expressed as the percentage of the control values (no preincubation with HLE or Cat G). Each histogram is the mean ± SEM of three to four distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f4.jpeg?Expires=1769364233&Signature=jYPKtaWnjW9hSYUiWWbKvM0b8RLUAsSKkrbi-WE5lp2Lsp4f7T-s2eMPfSXSQOmyybSU8uwcJecxSR4khfO50xEkL2kzHfl8AnN2NAcfF~-eg30sDjZVXwfT~UeAVkGw513MZSPzHe~RO9wst2VdDirAyeZkXsM9y7RB460f8aqqAwrQrX3Hic1Rj9jcxPyPB~qJ7wIRbHue7r9yanJZXKzwTVLzgeOR5LqLAHaZOFqDun~YiH9~Eg8ok7CYq5VKn0FrN4Woq3EtD-GsHFkQcwyUUE-WGbN0lbuQjpmC3N6CwazpEGL4Bo6qkehiCSkED1THXxijnVo7foLIpefj5A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 6. Effect of HLE, Cat G, and PR3 on platelet activation induced by thrombin or TRAP42-55. Stirred fura 2-loaded platelets were preincubated with buffer (A) or 600 nmol/L of each of the neutrophil proteinases (B to D). The preincubation time was 5 minutes except for Cat G (C), for which a longer period was required to allow the Ca2+ mobilization induced by this proteinase to return to the basal value. After stimulation of platelets with 5 nmol/L thrombin, platelets were further challenged with 6.25 μmol/L TRAP42-55. Changes in fluorescence intensity reflect changes in [Ca2+]i and are representative of three distinct experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/89/6/10.1182_blood.v89.6.1944/3/m_bl_0019f6.jpeg?Expires=1769364233&Signature=YPSon3KsqeJOUfDQga4~U6eoSpbdvvKXPiFVxMEIH0YC8GSKSl4wIZT5nLWUCrv4IywpniTXS6~CV4nP4Oq1ED2u3EDw-QWcl9JVArEn77hrnRypAFmge9nKrjGt9A~yUPRbQf9Nwd2cyHAmDhZ5f~Ct853zHBlDSsyya5L7NEYzykSL7cbas1uY6efxKZDfbMJlAJcK0Sam2bJpPV0RFGZv8AqQqU0eYIzNw7k1LCswh7yFOr5PQM6AfOIQtTheQkqlzf1ZFteL1elA~UQlSN5e9eA5mbKCyMiXQJ9llj1MOP~37sFOuRmA7-gZLQRLmDdJPOkbfcQCO7bT4MsLhg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)