Abstract

Types A and B Niemann-Pick disease (NPD) result from the deficient activity of the lysosomal hydrolase, acid sphingomyelinase (ASM). A long-term goal of our research is to evaluate the effects of bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy (HSCGT) on the NPD phenotype. As an initial step toward this goal, we have undertaken a study aimed at optimizing hematopoietic cell engraftment in acid sphingomyelinase “knock-out” (ASMKO) mice. Several parameters were analyzed, including the effects of radiation and donor cell number on survival and engraftment of newborn and adult animals, the number of donor cells detected in the brain posttransplantation, and the levels of ASM activity achieved in the brain. A total of 202 ASMKO and normal animals were transplanted and studied, and the overall conclusions were: (1) newborn ASMKO animals were more susceptible to radiation-induced mortality than normal animals, (2) at low radiation doses, increasing the donor cell number improved engraftment, while this was less evident at the higher radiation doses, (3) engraftment was easier to achieve in normal as compared with ASMKO animals, (4) among newborn transplants, the number of donor cells detected in the brain was directly correlated with engraftment in the blood, (5) more donor cells were detected in the brains of newborn ASMKO animals as opposed to newborn normal animals, and (6) no donor cells were found in the brains of animals transplanted as adults, including those that were highly engrafted in the blood. These results provide important information regarding the design of future BMT and HSCGT studies in ASMKO mice and other mouse models and demonstrate the potential of altering the NPD phenotype by these therapeutic strategies.

THE CURRENT STUDY was designed to use the “knock-out” mouse model of Niemann-Pick disease (NPD)1 to systematically evaluate the effects of radiation, age, donor cell number, and phenotype on survival, engraftment, and cell migration into the brain following bone marrow transplantation (BMT). In man, acid sphingomyelinase (ASM) deficiency leads to two types of NPD. Type A NPD is characterized by a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative course that leads to death by 3 years of age, while patients with Type B NPD have little or no neurologic involvement and may survive into adulthood.2 Although the precise cause of the NPD phenotype is unknown, presumably, the deficiency of ASM activity leads to an accumulation of sphingomyelin and cholesterol in various cell types (eg, macrophages, neurons), impairing normal cell function.2

Mice with NPD (ie, acid sphingomyelinase “knock-out” [ASMKO] mice) develop normally until about 4 months of age, when ataxia first becomes evident.1 They then follow a severe, neurodegenerative course that leads to death between 6 and 8 months of age. Affected animals have no detectable ASM activity in their tissues or fluids, and blood cholesterol levels and sphingomyelin in the liver and brain are markedly elevated. Atrophy of the cerebellum and a dramatic deficiency of Purkinje cells is evident. Microscopic analysis showed “NPD” foam cells in reticuloendothelial organs and characteristic NPD lesions in the brain. Thus, the ASMKO mice are an authentic model of human NPD that is useful for the study of disease pathogenesis and the development of therapeutic strategies.

The ASM gene encodes at least two forms of the enzyme: one is an intracellular form thought to be localized in the lysosomes, and the second is a zinc-activated enzyme that is secreted from a wide range of cell types, including macrophages and microglia.3 If BMT is to be therapeutic for NPD, it is likely that BM-derived cells in the blood and other organs (eg, Kupffer cells in the liver) must release sufficient ASM for uptake by nonhematopoietic cells and lead to metabolic “cross-correction.”

While treatment of the nonneurologic, Type B form of NPD by this therapeutic approach should be feasible, as the primary cellular sites of pathology are the resident macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system,2 BMT in Type A NPD patients will only be successful if BM-derived cells (or ASM itself ) migrate across the blood brain barrier (BBB) and release ASM for uptake and “cross-correction” of neurons. The brain is composed of two general cell types, the glia and the neurons. The glia function as support cells in the central nervous system (CNS) and are subdivided according to their morphology and function into macroglia and microglia.4 Microglia are considered analogous to tissue macrophages and, similar to macrophages, derive from hematopoietic progenitor cells.5-13

In recent years, a large body of BMT studies in normal mice or murine disease models have shown that BM-derived cells can cross the BBB and establish resident cells in the CNS.14-25 BMT studies for several human neurologic disorders have also supported this conclusion.26-28 However, in many of the animal studies, the recipients were subjected to lethal doses of radiation before the transplantation, a treatment that may transiently disrupt the BBB and lead to severe pathologic side effects, particularly in young animals.21 29-31

The results in this report clearly demonstrate that transplanted hematopoietic cells can cross the BBB and enter the CNS of newborn animals when low doses of myeloablative radiation are used. This is in stark contrast to animals transplanted as adults, where no donor-derived cells were detected in the brain, even after exposure to 800 cGy and nearly complete engraftment in the blood. These studies lay the foundation for the development of future hematopoietic stem cell-mediated gene therapy (HSCGT) for NPD and other neurologic diseases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BMT.The ASMKO mouse colony was established from heterozygous breeding pairs obtained by gene targeting of 129/Sv embryonic stem cells and subsequent microinjection into C57BL/6 blastocysts.1 Gender-mismatched BMTs were performed using normal male mice (6 to 12 weeks old) obtained from within the ASMKO colony as donors. Donor animals were killed by cervical dislocation and the BM cells were harvested from the femurs and tibia by flushing the medullary cavities using Hanks' balanced salt solution (GIBCO-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and a 27-gauge needle. The cells were washed twice in Hanks' solution and single cell suspensions were obtained by passage through a cell strainer (40 μm, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). These cells were then counted, diluted to the desired concentration, and immediately injected into the tail vein of adults or, in the case of newborns, divided in half and injected into both the temporal vein and peritoneal cavity. The recipients were either nonirradiated or subjected to a single total body dose of 200, 400, or 800 cGy from a dual137 Cs source (dose rate = 80 cGy/min), and were normal or ASMKO newborns (1 to 4 days old) or adults (6 to 12 weeks old). Age-matched littermates (normal and ASMKO) were used as radiation controls (ie, irradiated, but not transplanted). No antibiotics or other supportive care were given to any of the animals after transplantation.

Tissue harvesting and preparation.Three months post-BMT, animals were anesthetized with Ketamine (Sigma, St Louis, MO; 0.5 g/kg of body weight) and subjected to cardiac perfusion. An incision was made in the right atrium to allow blood to flow out and a cannula was introduced through the left ventricle into the aorta, delivering 50 mL of warm 0.9% NaCl solution. After perfusion, tissues were collected and immediately frozen on dry ice for subsequent sectioning or enzyme analysis (see below).

In Situ Hybridization

Blood.Peripheral blood was obtained by retinal orbit bleeding and white blood cells (WBCs) were isolated after lysis of the red blood cells using a hemolytic buffer (0.1 mol/L NH4Cl, 12 mmol/L NaHCO3 , 10 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0). WBCs were fixed in Carnoy's solution (methanol-acetic acid 3:1) and spotted on microscope slides (Baxter Scientific, McGraw Park, IL). The cells were treated with 0.1 mol/L HCl containing 0.05% Triton X-100 for 7.5 minutes at 37°C, fixed in 1% buffered paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes at 24°C, and then dehydrated in ethanol. Hybridizations were performed by incubating the slides overnight in a humidified chamber at 37°C with a solution (2× SSC, 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.1% Tween 20, 0.5 mg/mL salmon sperm DNA) containing 4 ng/μL of biotinylated Y-chromosome specific probe M34.32 After hybridization, the slides were washed, and development was performed using a fluorescein avidin conjugate (5 μg/mL) (Sigma), followed by amplification with biotinylated antiavidin (2 μg/mL) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Subsequently, a second incubation/amplification with the fluorescein avidin conjugate was performed. The cells were then counterstained with propidium iodide (100 μg/mL) (Sigma) and mounted in antifade medium (0.01 mol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.5 containing 20 mg/mL of DABCO [triethylenediamine-1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane; Sigma, in glycerol). A total of 300 nuclei were scored to determine the percentage of donor-derived cells in the blood of the transplant recipients.

Brain sections.Ten-micron frozen sagittal brain sections were incubated for 10 minutes in 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 mol/L triethanolamine HCl/0.9% NaCl, pH 8.0. The sections were then dehydrated and delipidated in ethanol and chloroform, respectively, treated with Proteinase K (2.5 μg/mL), and incubated for 7.5 minutes in 0.1 mol/L HCl containing 0.05% Triton X-100 at 37°C. They were then fixed in 1% buffered paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 24°C. Probe hybridizations were performed as described above.

To estimate the number of donor-derived cells in the brain, half of each recipient brain was surveyed by collecting every 25th section, counting the number of Y-chromosome positive cells using a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Oberkochen, Germany), and plotting each location according to illustrations from an atlas of the mouse brain.33 The number of donor cells/section was then multiplied by 50 to estimate the total number of cells in the brain. The sections were photographed using a Leica TCS4D confocal microscope (Heidelberg, Germany).

Synthesis of fluorescent sphingomyelin.Sphingomyelin, to which the fluorescent probe BODIPY was linked covalently (BODIPY dodecanoyl sphingosyl phosphocholine; BOD12-SPM), was synthesized essentially as described previously for lissamine rhodamine sphingomyelin,34 except that BODIPY dodecanoic acid (Molecular Probes Inc, Eugene, OR) was condensed with sphingosyl phosphocholine.

Enzyme analysis.ASM activity was detected using fluorescent sphingomyelin derivatives. WBCs or brain tissues were obtained as described above and homogenized in 0.2% Triton X-100 on ice using three 10-second bursts of a Potter-Elvehjem tissue homogenizer (Thomas Scientific, Sweedesboro, NJ). Total protein was determined by the method of Stein et al.35 The standard 40 μL ASM assay mixture consisted of 30 μL of sample (homogenized cells) and 2 nmol of BOD12-SPM suspended in 0.1 mol/L sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.2 containing 0.6% Triton X-100 and 5 mmol/L EDTA (for detection of the lysosomal ASM activity) or 0.1 mmol/L ZnCl2 (for detection of the secreted, zinc stimulated ASM activity).

After incubating the assay mixture at 37°C (up to 3 hours), the samples were loaded on thin layer chromatography plates (TLC LK6 D Silica gel 60, Whatman, Clifton, NJ) and resolved using chloroform/methanol (95:5, vol/vol). After resolution, the band containing the fluorescently labeled ceramide was scraped from the TLC plates, extracted in chloroform/methanol/water (1:2:1, vol/vol) for 15 minutes at 55°C, and quantified in a spectrofluorometer (fluorescence spectrophotometer 204-A, Perkin Elmer). The excitation and emission wavelengths of the instrument were set at 505 and 530 nm, respectively.

Statistical analyses.Analysis of variance was performed using the general linear models (GLM) procedure of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software package (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Data on blood and brain engraftment were available for 38 ASMKO and 95 normal mice, which were divided into several radiation/cell dose groups. This included animals that were transplanted perinatally (n = 91) or as adults (n = 42); all of the transplanted animals were analyzed for engraftment 3 months posttransplant. For these statistical analyses, the complete data set was analyzed to take into account the individual and combined effects of genotype, radiation, bone marrow cell dose, and age at transplant. As described in the Results, newborn ASMKO mice survived only low doses of radiation. Thus, the data set is substantially unbalanced across age, and the two age groups were therefore separated for the statistical evaluations. Significant effects (Type III SS) are provided (see Tables 1 and 3).

RESULTS

Engraftment as a function of radiation dose, recipient age, genotype, and cell dose.To access the effects of various engraftment parameters in BMT recipients, a series of gender-mismatched transplants (male into female) were performed so that in situ hybridization could be used to monitor chimerism with a Y-chromosome specific probe.32 Figure 1 and Table 1 show that in newborn and adult mice, blood engraftment was significantly affected by cell dose, radiation dose, and/or genotype. These data also showed that newborn ASMKO mice engrafted less than normal mice (Fig 1) and had increased mortality at higher radiation doses (ie, above 200 cGy) (Table 2). Among adult animals, similar trends were evident, but less dramatic.

Engraftment as a function of radiation dose, age, genotype, and donor cell number. For the newborn transplants, 18, 25, 16, and 13 female transplant recipients were analyzed for the 0, 200, 400, and 800 cGy groups, respectively. For the adult transplants, 10, 11, 12, and 9 female recipients were analyzed for each group, respectively (▪, normal; ○, ASMKO). Engraftment = the number of male cells detected among 300 nuclei analyzed in the female recipients. A t-test analysis showed that engraftment was signficantly less in the ASMKO mice as compared with normal mice (see Table 1).

Engraftment as a function of radiation dose, age, genotype, and donor cell number. For the newborn transplants, 18, 25, 16, and 13 female transplant recipients were analyzed for the 0, 200, 400, and 800 cGy groups, respectively. For the adult transplants, 10, 11, 12, and 9 female recipients were analyzed for each group, respectively (▪, normal; ○, ASMKO). Engraftment = the number of male cells detected among 300 nuclei analyzed in the female recipients. A t-test analysis showed that engraftment was signficantly less in the ASMKO mice as compared with normal mice (see Table 1).

Among 28 animals that were transplanted without receiving prior radiation (newborn and adult), blood engraftment was < 10% (Fig 1). In contrast, among newborn animals subjected to a single radiation dose of 200 cGy before transplant (n = 25), engraftment ranged from 11% to 98%; notably, none of the 200 cGy animals transplanted as newborns failed to engraft. In general, engraftment in the newborns was proportional with the donor cell number, particularly within the 200 and 400 cGy groups (Fig 1) and continued to increase up to 8 months posttransplant (not shown).

In contrast to the results with newborns, none of the adult animals (n = 11) receiving 200 cGy engrafted more than 10%. However, it should be recognized that although the same number of cells were injected into the newborn and adult recipients, the cell dose (ie, cell number injected/g body weight), was significantly less in the adults than the newborns (Fig 1). To achieve engraftment in the adult animals, radiation doses of 400 cGy or higher were required; indeed, at the 400 cGy dose, nearly all of the adult animals receiving a cell dose greater than or equal to 3 × 105/g engrafted. Increasing the radiation dose from 200 to 400 cGy also led to increased engraftment in the newborn recipients, but was much less critical than in adult animals.

Radiation with a “lethal” dose of 800 cGy led to high engraftment in both newborn and adult recipients, although all of the 1-day-old newborn animals (ASMKO or normal) treated with this radiation dose died within 1 week (Table 2). However, among 4-day-old recipients, ASMKO animals were notably more susceptible to radiation-induced mortality than normal animals. Even at a “sublethal” radiation dose of 400 cGy, the mortality among 1-day-old ASMKO newborns was much higher than among normal newborns. A similar trend was evident among ASMKO and normal adult animals (ranging in age from 6 to 12 weeks), although to a much less degree, and no statistically significant differences in survival and engraftment were seen among these different adult age groups. Importantly, the 200 cGy radiation dose did not lead to increased mortality among any of the animals treated.

As an additional measure of engraftment, WBC ASM activity assays were performed on all of the ASMKO animals surviving transplantation. In successfully engrafted female ASMKO animals, the in vitro ASM activities correlated extremely well with the Y-chromosome in situ results (correlation coefficient = 0.99; data not shown). Based on this result, an additional set of 20 ASMKO 1-day-old animals (10 each male and female) were subjected to 200 cGy and transplanted with normal male cells. ASM assays of the peripheral blood WBCs showed that there was a slight improvement in the gender-matched transplants as opposed to those that were gender-mismatched (Fig 2), although these differences were not statistically significant.

Comparison of engraftment in gender-matched and mismatched transplants. To compare engraftment in the gender-matched (▪) and mismatched (▴) transplants, ASM activities were determined. For this comparison, the transplants were performed on 1-day old ASMKO animals subjected to 200 cGy of radiation before the transplant, and receiving 3 × 107 normal cells/g of body weight. 1 U = the amount of BODIPY-ceramide produced/hour/mL. The mean and standard error of the mean are plotted in the graph. Note that although the mean values are higher for gender-matched transplants as compared with gender-mismatched, the differences are not statistically significant. The t-test values for months 1, 2, and 3 were t = 1.84/P = .079, t = 0.847/P = .415, and t = 1.13/P = .272, respectively.

Comparison of engraftment in gender-matched and mismatched transplants. To compare engraftment in the gender-matched (▪) and mismatched (▴) transplants, ASM activities were determined. For this comparison, the transplants were performed on 1-day old ASMKO animals subjected to 200 cGy of radiation before the transplant, and receiving 3 × 107 normal cells/g of body weight. 1 U = the amount of BODIPY-ceramide produced/hour/mL. The mean and standard error of the mean are plotted in the graph. Note that although the mean values are higher for gender-matched transplants as compared with gender-mismatched, the differences are not statistically significant. The t-test values for months 1, 2, and 3 were t = 1.84/P = .079, t = 0.847/P = .415, and t = 1.13/P = .272, respectively.

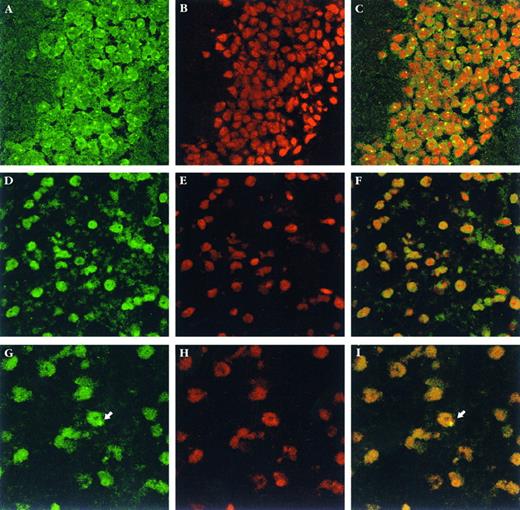

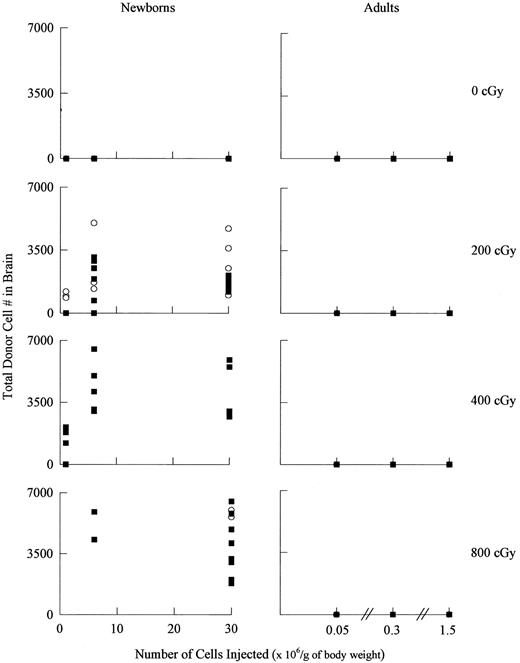

Donor-derived cells and enzyme analysis in the brain.To monitor the presence of donor-derived cells in the brain, Y-chromosome in situ hybridization was performed in brain sections (Fig 3). Donor-derived cells were distributed uniformly throughout the brains of newborn recipients and were evident in the cerebral cortex, thalamus, and other forebrain structures, as well as brain stem and cerebellum. No special association was seen with choroid plexus, ependyma or subependymal zones. Notably, no donor-derived cells were detected in the brains of animals transplanted as adults, irrespective of the radiation dose, number of cells transplanted, or degree of engraftment in the blood (Fig 4). In contrast, among newborns, donor cells were detected in the brains of most engrafted recipients, although the number of donor-derived cells was low and increasing the radiation dose from 200 to 800 cGy did not dramatically improve this result (Fig 4). Figure 5 and Table 3 illustrate that there was a clear correlation between the degree of blood engraftment in the newborn group and donor cell entry into the brain, and that brain engraftment was better in ASMKO newborns than normals.

Y-chromosome in situ hybridization in brain sections. (A through C) male brain sections; (D through F ) female brain sections; (G through I) transplanted female brain sections. The total number of donor cells in the brain was estimated by counting individual male cells in 1 of every 25 sagittal sections from half of the brain and then multiplying this number by 50 (see Materials and Methods for details). The arrows indicate a single male cell found in one representative section from a female transplant recipient. (A, D, and G) Show the fluorescein-labeled hybridization signal; (B, E, and H) show counterstaining with propidium iodide, and (C, F, and I) show combined images. Magnification = 1,000× for (A) through (F ), and 1,200× for (G) through (I).

Y-chromosome in situ hybridization in brain sections. (A through C) male brain sections; (D through F ) female brain sections; (G through I) transplanted female brain sections. The total number of donor cells in the brain was estimated by counting individual male cells in 1 of every 25 sagittal sections from half of the brain and then multiplying this number by 50 (see Materials and Methods for details). The arrows indicate a single male cell found in one representative section from a female transplant recipient. (A, D, and G) Show the fluorescein-labeled hybridization signal; (B, E, and H) show counterstaining with propidium iodide, and (C, F, and I) show combined images. Magnification = 1,000× for (A) through (F ), and 1,200× for (G) through (I).

Donor-derived cells in the brains of transplanted recipients as a function of radiation dose, age, genotype, and donor cell number. For the newborn transplants, 18, 25, 16, and 13 female transplant recipients were analyzed for the 0, 200, 400, and 800 cGy groups, respectively. For the adult transplants, 10, 11, 12, and 9 female recipients were analyzed for each group, respectively (▪) normal; (○) ASMKO. A t-test analysis showed that brain engraftment was significantly higher in the ASMKO mice as compared with normal mice (see Table 3).

Donor-derived cells in the brains of transplanted recipients as a function of radiation dose, age, genotype, and donor cell number. For the newborn transplants, 18, 25, 16, and 13 female transplant recipients were analyzed for the 0, 200, 400, and 800 cGy groups, respectively. For the adult transplants, 10, 11, 12, and 9 female recipients were analyzed for each group, respectively (▪) normal; (○) ASMKO. A t-test analysis showed that brain engraftment was significantly higher in the ASMKO mice as compared with normal mice (see Table 3).

Correlation of engraftment in the brain and blood of normal and ASMKO newborn mice. (▪) Represents normal animals and (○) represents ASMKO animals. The correlation coefficient for normal animals was 0.704 and 0.889 for ASMKO animals.

Correlation of engraftment in the brain and blood of normal and ASMKO newborn mice. (▪) Represents normal animals and (○) represents ASMKO animals. The correlation coefficient for normal animals was 0.704 and 0.889 for ASMKO animals.

In addition to the Y-chromosome analysis, ASM activities also were measured in the brains of the transplanted ASMKO animals. In the absence of zinc, no ASM activities were detected in brain homogenates, while in the presence of 0.1 mmol/L ZnCl2 , a small amount of activity (from 2% to 8% of normal) was found in 10 of 19 animals transplanted as newborns. Overall, the levels of ASM activity were proportional with the number of donor cells detected by the Y-chromosome analysis (not shown).

DISCUSSION

The long-term goal of our studies is to use the ASMKO mouse model of NPD to develop and evaluate BMT and HSCGT for the treatment of this disorder. Analogous approaches have been evaluated for a variety of other lysosomal storage diseases,36 and BMT has been undertaken in three NPD patients.37-39 The results of these latter studies have shown that BMT alone is not sufficient to elicit a complete therapeutic effect in this disorder and suggests that transplantation with genetically modified, overexpressing cells may be required. The work in this report represents the first step towards this goal, which is the development of an optimal transplantation protocol that will facilitate engraftment in NPD individuals without causing high mortality or pathology. Several parameters were evaluated, including radiation dose, cell dose, and the age and phenotype of the recipient animals. Particular attention was paid to engraftment in the brain, as a major pathologic component of Type A NPD resides in the CNS. Although many studies have been performed to evaluate donor cell entry into the brains of transplant recipients,40-44 our study systematically analyzed this phenomenon in a unique neurodegenerative animal model.

Among the notable results, engraftment was achieved in the majority of newborn animals subjected to a low dose of radiation, 200 cGy, while animals that were not irradiated did not engraft. The 200-cGy dose did not cause mortality in the recipients, nor did it lead to any neural or visceral pathology. Unlike newborns, to achieve engraftment in adults, a radiation dose of 400 cGy or higher was required. However, the likely explanation for this finding relates to the fact that although the same total number of cells was injected into the newborn and adult animals, the cell dose (ie, number of cells injected/g body weight) was markedly less in the adults than the newborns.

Notably, blood engraftment was significantly higher in normal animals (newborn or adult) than ASMKO animals. This result is intriguing because we have recently shown that certain NPD cell types (eg, lung epithelia) are resistant to radiation-induced cell death.45 Thus, it is possible that we did not achieve the same degree of radiation-induced myeloablation in the ASMKO recipients as we did in the normal recipients, and less “space” was therefore available for donor cell engraftment. The effects of radiation on NPD hematopoietic cells is currently under investigation in our laboratory to confirm this hypothesis.

Another striking result obtained from these studies was the fact that newborn ASMKO mice were more susceptible to radiation-induced death than normal newborn mice. This result was not due to the negligence of ASMKO mothers, as only nonaffected, heterozygous mothers were used. On the surface, this finding may seem in conflict with the fact that certain cell types in the ASMKO mice are radiation resistant.45 However, it must be noted that the mechanism(s) underlying the increased mortality of the ASMKO mice observed in the present study are unknown, and likely to be complex. Indeed, in the previously published report on radiation resistance,45 only two tissues were analyzed, lung and thymus. Moreover, in that report, the radiation doses and time course were completely different from those used in the present work.

With regards to the CNS, our results confirm the fact that the BBB of newborn animals is more amenable to hematopoietic cell migration than that of adults. Among all of the adult transplant recipient animals analyzed, including those subjected to a high radiation dose of 800 cGy and almost completely engrafted in the blood, no donor-derived cells were found in the brain. In contrast, among newborn recipients, donor-derived cells could be found in the majority of the animals, even those subjected to a low dose of 200 cGy and only partially engrafted in the blood. These donor cells were not due to blood contamination, as cardiac perfusion was performed before harvesting the brain tissue, and only the donor cells found in the brain parenchyma (not in the leptomeninges or blood vessels) were counted.

In general, the degree of brain engraftment in newborns correlated well with the degree of engraftment in the blood, however, significantly more brain engraftment was observed in ASMKO animals as compared with normal animals. It is possible that the neurodegenerative state of the ASMKO brain provides a better engraftment environment than the normal brain because more bone-marrow derived cells may be permitted to migrate into the diseased brain for immunologic surveillance. However, it is important to recognize that although some donor cells were usually found in the brains of animals transplanted as newborns (ASMKO or normal), the total number of donor cells/animal was very low. Despite this finding, up to 8% of normal ASM activity was detected in the newborn ASMKO transplant recipients. Because the detection of this activity was dependent on the addition of zinc, it may be assumed that this represents the secreted form of ASM.3 Indeed, because the animals were perfused before being killed, it is possible that even higher amounts of ASM activity were secreted by the small numbers of donor cells.

Most of the studies cited in this report describe data obtained 3 months posttransplantation. This time point was chosen for a variety of reasons, including an established literature documenting that engraftment in transplanted mice occurs by 1 month46 and the fact that maximal infiltration of microglia precursor cells into the CNS takes place by 3 months.9 However, it is possible that the number of donor-derived cells present in the recipient animals continues to increase beyond the 3-month time point.10 Indeed, in a small group of ASMKO animals (n = 10) that were subjected to 200 cGy and analyzed at 8 months posttransplant (not shown), the number of donor-derived cells found in the brain was increased as compared with those analyzed at 3 months. While the explanation for this finding is unknown, it is possible that donor-derived cells continued to migrate into the CNS of these animals throughout the entire 8-month study period, or, more likely, donor cells that had entered the CNS soon after radiation/transplantation continued to divide and provide more enzyme-expressing cells within the brain.

Thus, these studies provide important data concerning the design of BMT and/or HSCGT trials for NPD. In particular, they show that although both approaches may be considered for NPD patients, important parameters such as preconditioning by radiation and the age of the transplant recipients must be considered in the planning of a clinical protocol. In addition, it must be recognized that the direct extrapolation of these murine results to the treatment of human NPD patients cannot be performed. Current studies are under way to evaluate the complete biochemical, pathological, and clinical effects of BMT and HSCGT in ASMKO mice as a prelude to future human trials.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the expert assistance of Dr Rebecca Hardy and Sunghae Yoon from the Brookdale Center for Molecular Biology, and Dr Deanna L. Benson and Ayreh Cohen from the Arthur M. Fishberg Center for Neurobiology at the Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Supported by Grants No. HD 28607 and HD 32654 from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD), Grant No. 1-2224 from the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation (White Plains, NY), Grant No. RR 0071 from the National Center for Research Resources for the Mount Sinai General Clinical Research Center, and Grant No. 93-00015 from the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation (Jerusalem, Israel).

Address reprint requests to Edward H. Schuchman, PhD, Department of Human Genetics, Box 1497, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, NY 10029.