Abstract

We reviewed the records and reevaluated 212 patients with aplastic anemia transplanted at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) between 1970 and 1993 who survived ≥2 years and who have been followed for up to 26 years. Parameters analyzed included hematopoietic function, chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), skin disease, cataracts, lung disease, skeletal problems, posttransplant malignancy, depression, pregnancy/fatherhood, and the return to work or school, as well as patient self-assessment of physical and psychosocial health, social interactions, memory and concentration, and overall severity of symptoms. Survival probabilities at 20 years were 89% for patients without (n = 125) and 69% for patients with chronic GVHD (n = 86) (the status was uncertain in 1 surviving patient). All patients had normal hematopoietic parameters. Skin problems occurred in 14%, cataracts in 12%, lung disease in 24%, and bone and joint problems in 18% of patients. Eleven patients (12%) developed a solid tumor malignancy and 19% of patients experienced depression. Chronic GVHD was the dominant risk factor for late complications. Seventeen patients died at 2.5 to 20.4 years posttransplant; 13 of these had chronic GVHD and related complications. At 2 years, 83% of patients had returned to school or work; the proportion increased to 90% by 20 years. At least half of the patients preserved or regained the ability to become pregnant or father children. Patients rated their quality of life as excellent and symptoms as minimal or mild. In conclusion, marrow transplantation in patients with aplastic anemia established long-term normal hematopoiesis. No new hematologic disorders occurred. The major cause of morbidity and mortality was chronic GVHD. However, the majority of patients who survived beyond 2 years returned to a fully functional life.

WITH THE CHARACTERIZATION in the 1960s of the human major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens, termed HLA, marrow transplantation from an HLA-matched donor became a realistic treatment option.1-3 Patients with severe aplastic anemia were thought to present an ideal indication for transplantation: hematopoietic stem cells from a normal donor would replace the nonfunctioning marrow. Failure of sustained engraftment was a major complication in early trials,4,5 but has been infrequent in recent studies.6-8 Improved prophylaxis of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)9,10 has resulted in survival of 90% of patients transplanted from an HLA-matched related donor.11 As more patients have been observed for extended periods of time after transplantation, some delayed complications have been recognized,12,13 but only few studies have analyzed long-term results.14-16 We have established a comprehensive program to offer long-term service to transplant recipients and to conduct investigations into delayed effects after marrow or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The present analysis assessed long-term outcome in patients with aplastic anemia who had survived a minimum of 2 years posttransplant and who have been followed for up to 26 years.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Between 1970 and 1993, 370 patients with aplastic anemia received a first marrow transplant at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC).3,6,10,11,17 18 The present analysis focused on the 212 patients who survived for at least 2 years and who did not experience graft rejection or receive a second transplant. Demographic data are summarized in Table 1: 187 patients (88%) received a transplant from an HLA-identical sibling donor, 17 (8%) from an HLA-nonidentical related donor, 3 (1%) from a monozygotic twin, and 5 (2%) from an unrelated volunteer donor.

Conditioning regimen and posttransplant care.

Conditioning regimens consisted of cyclophosphamide, antithymocyte globulin (ATG), and total body irradiation (TBI) administered alone or in combination. In addition to donor marrow, 66 patients also received infusions of viable donor buffy coat cells as an antirejection measure (Table 1). Among 209 patients transplanted from an allogeneic donor, 86 received GVHD prophylaxis with methotrexate (MTX) plus cyclosporine (CSP), 111 with MTX, 7 with CSP, and 5 with other combinations.3,10,19 Fifty-five patients (26%) developed acute GVHD grades II-IV20 and were treated as described.21 Eighty-six patients developed chronic GVHD and received glucocorticoids, CSP, and less frequently other agents for therapy.22 Other posttransplant supportive care has been described.3,10,11 17-22

Long-term follow-up.

All patients underwent a “departure work-up” 3 months after transplantation21 and all patients returned to the FHCRC at 1 year (and sporadically thereafter) for a “complete” evaluation.23 Follow-up consisted initially of 6-monthly and later of annual contacts with the physician's office and mailing of a questionnaire to the physician to obtain objective data. If no response was received within 2 months, a second letter was mailed.

Patients were contacted once yearly on their transplant anniversary, and, beginning in August 1990, were mailed questionnaires. Last contact with more than 96% of patients was within the past 5 years. Among the 6 patients without contact for 5 years, the minimum follow-up (at last contact) was 9 years. The patients' responses supplemented results obtained from the physicians and provided a self-assessment of performance and well-being using visual analog scales.24

Considered under complications were (1) skin disease that was cosmetically disturbing (scleroderma) or required physical therapy (contractures); (2) cataracts diagnosed incidentally or because of visual impairment; (3) lung disease (chronic obstructive or restrictive disease) as indicated by impaired performance or by pulmonary function tests at a level less than 80% of predicted; (4) musculoskeletal problems causing pain or requiring therapy (osteoporosis; avascular necrosis with or without joint replacement); (5) depression (requiring therapy; suicidal attempts; suicide); (6) malignancy (invasive or in situ) developing after transplantation. We also ascertained whether female patients had become pregnant or whether male patients had fathered children.25

Statistical analysis.

Demographic data are reported using range and median values for continuous variables. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, censoring at the time of last contact. The time scale on the survival figures begins at 2 years posttransplant, as patients had to survive that long to be included in the study. Late complications were estimated with cumulative incidence curves, treating death before the event of interest as a competing risk and censoring at the time of last contact.26 27 The probabilities of continuing chronic GVHD or death with chronic GVHD were calculated using cumulative incidence methods. The impact of various factors on late complications and survival was determined by univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses. Time to each of the following endpoints was used: chronic GVHD, skin disease, cataracts, lung disease, skeletal complications, depression, and pregnancy (or fathered pregnancy). Time was censored at the date of last contact (or death for nonsurvival models). For complications occurring more than once, time to first occurrence was used. For analysis of pregnancy, patients were considered at risk only at age ≥16 years at the time of analysis (but might have been preadolescent at the time of transplantation). Prognostic variables examined for their impact on late complications included age at transplant, gender, prior acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, use of ATG in the conditioning regimen, buffy coat, CSP alone or in combination with other agents, and year of transplant. For multivariable analysis, final models were determined based on step-down regression methods (using P < .10 as inclusion criterion) where year of transplant was forced into all models to account for potential changes over time.

In addition to the objective data, yearly questionnaires addressed self-perceived physical and psychological health, social interactions, memory and concentration, overall severity of symptoms (on visual analog scales), and whether patients had returned to work or school. For each patient, we selected the questionnaire returned closest to the midpoint of each time interval studied and compared responses between groups with and without chronic GVHD and between children (<18 years) and adults for each time interval. Comparisons were made using a Wilcoxon's rank sum test or a χ2 test. Time intervals (midpoints) posttransplant were: 1 to 3 (2), 3 to 7 (5), 8 to 12 (10), 13 to 17 (15), and 18 to 22 (20) years. Because questionnaires were sent beginning only in 1990, each interval contained patients transplanted within different periods of time; it was not possible to separate the impact of time since transplant from that of transplant year.

RESULTS

Survival.

Patients have been followed for 2 to 26 years (median, 12 years) posttransplant and are currently 7 to 58 years old (median, 32 years old). Actuarial 20-year survival among patients without chronic GVHD (n = 125) was 89%, compared with 69% in patients with chronic GVHD (n = 86) (in 1 surviving patient, the GVHD status was uncertain). All 3 syngeneic recipients, 15 of 17 patients receiving HLA-nonidentical related transplants, and all 5 patients receiving unrelated transplants are currently surviving. All patients have normal hematologic parameters.

For patients without chronic GVHD, the minimum, mean, and maximum Karnofsky scores were 30 (a patient with recent surgery), 97, and 100, respectively (75th percentile, 100), compared with 60, 95, and 100 (75th percentile, 90) in patients with chronic GVHD (differences not significant). Scores were comparable for patients receiving HLA-identical or HLA-nonidentical or unrelated transplants, and no significant impact of age (<18 and ≥18 years) was observed. Similarly, no significant differences in Karnofsky scores were noted between patients who were 2 to 5, 6 to 10, 11 to 15, 16 to 20 or more than 20 years after transplant.

Delayed effects.

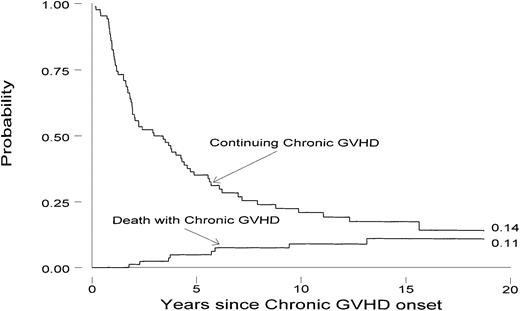

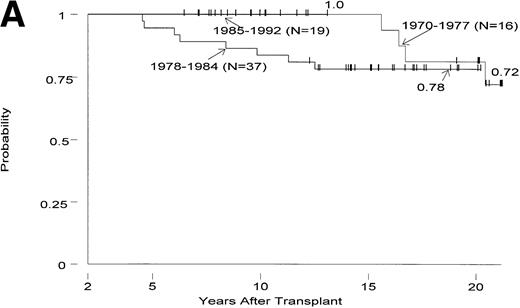

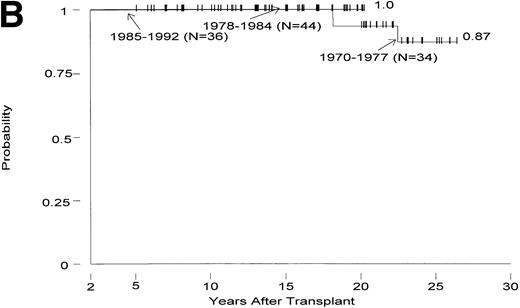

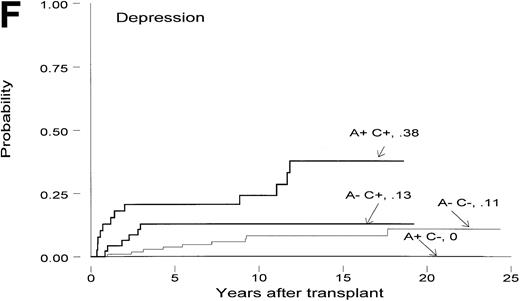

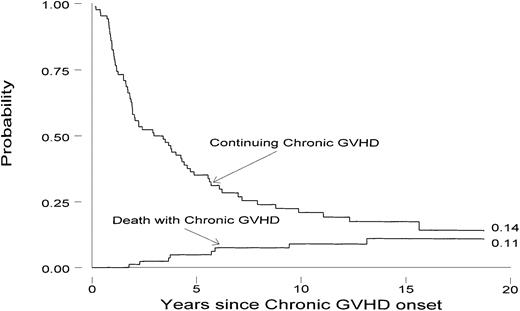

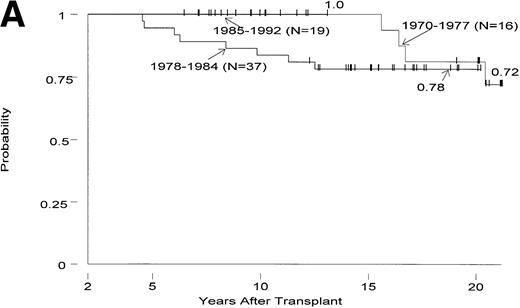

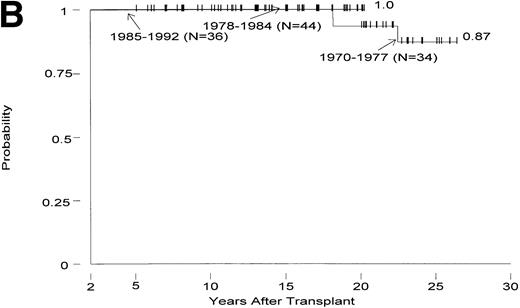

Among the 209 allogeneic recipients, 86 (41%) had chronic GVHD. Risk factors are summarized in Table 2. The incidence was higher after prior acute GVHD, but resolution of chronic GVHD occurred over a similar time period. Five years after chronic GVHD onset, 4% of patients had died with the disease, 64% had recovered, and 32% were on treatment. At 10 years, 8% of patients had died and 10% were still requiring therapy (Fig 1). The effect of chronic GVHD on survival among patients transplanted from an HLA-identical related donor is shown in Fig 2. Among patients without chronic GVHD (Fig 2A), the probabilities of survival were comparable for cohorts transplanted in 1970 to 1977 (87%), 1978 to 1984 (100%), and 1985 to 1992 (100%) (P = .29). Among patients with chronic GVHD, the probabilities of survival for the same time intervals were 72%, 78%, and 100%, respectively (Fig 2B). In univariable analysis, prior acute GVHD (P < .001), viable donor buffy coat infusion posttransplant (P < .001), and patient age (P = .001) significantly increased the risk of chronic GVHD; there was a suggestion that ATG administered as part of the conditioning regimen had a protective effect (P = .09). In multivariable analysis, acute GVHD (P < .001) and donor buffy coat infusion (P < .001) were significant risk factors; year of transplant had a marginally significant effect (lower incidence in recent years; P = .07) on the development of chronic GVHD.

Chronic GVHD. Probability of continuing chronic GVHD and death with GVHD over time after onset of chronic GVHD.

Chronic GVHD. Probability of continuing chronic GVHD and death with GVHD over time after onset of chronic GVHD.

Survival by year of transplant (1970 to 1977; 1978 to 1984; 1985 to 1992) in patients transplanted from a matched related donor. (A) In patients with chronic GVHD. (B) In patients without chronic GVHD.

Survival by year of transplant (1970 to 1977; 1978 to 1984; 1985 to 1992) in patients transplanted from a matched related donor. (A) In patients with chronic GVHD. (B) In patients without chronic GVHD.

Analyses of factors affecting other late events are shown in Table 3. Chronic GVHD and risk factors for chronic GVHD also had an impact on other late complications. Univariable analysis suggested that the use of CSP (GVHD prophylaxis) and ATG (conditioning regimen) were associated with a higher probability of posttransplant pregnancy than patients not exposed to those agents; only year of transplant was significant in multivariable analysis (higher probability in recent years; P = .002).

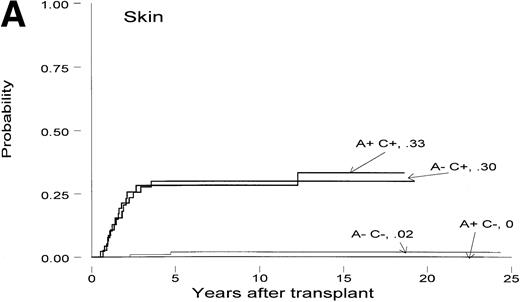

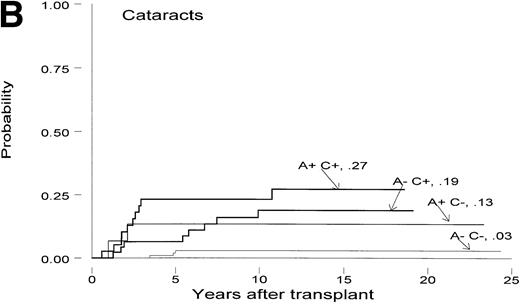

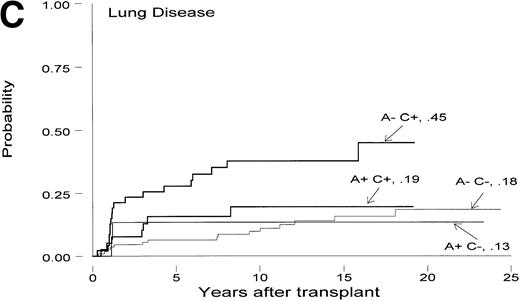

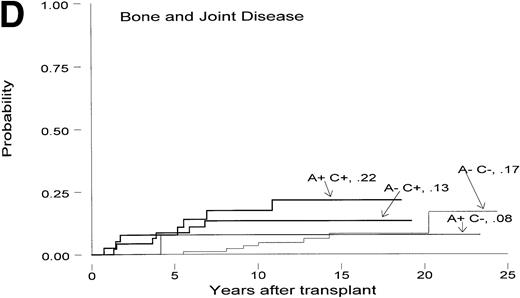

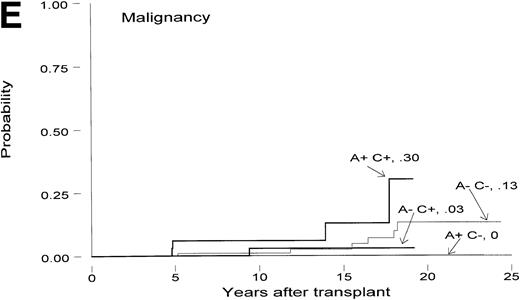

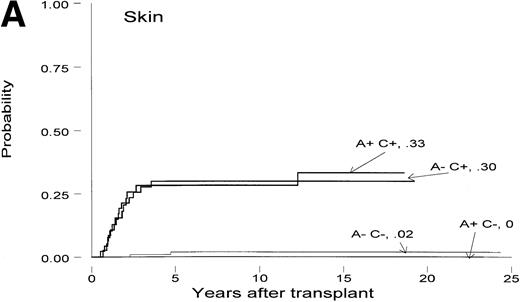

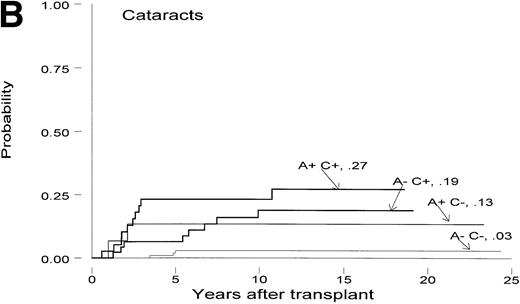

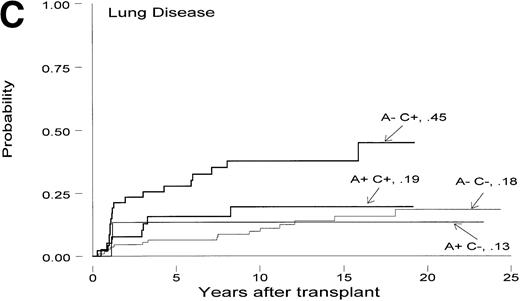

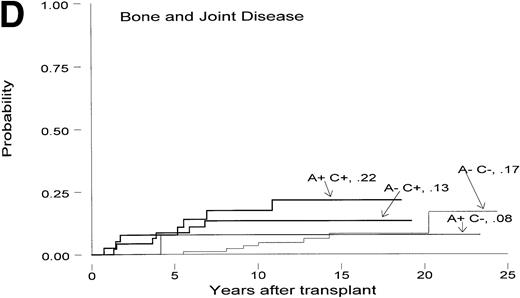

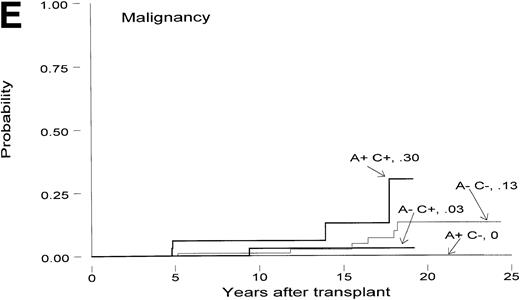

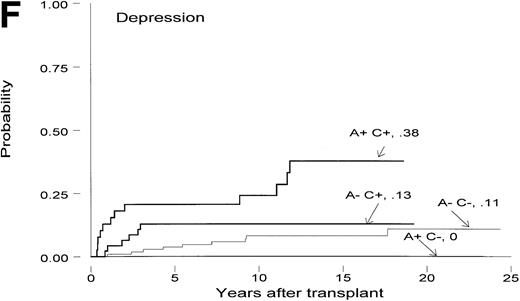

The cumulative incidences of several endpoints are shown in Fig 3A through F. For this analysis, patients were divided into four groups: (1) no acute, no chronic GVHD (A−C−; n = 110); (2) acute, but no chronic GVHD (A+C−; n = 15); (3) no acute, but chronic GVHD (A−C+; n = 47); and (4) both acute and chronic GVHD (A+C+; n = 39). Chronic skin problems, including scleroderma and contractures (Fig3A) occurred in 14% of patients ranging from 0% to 2% in patients without to 30% to 33% in patients with chronic GVHD (with or without preceding acute GVHD). Cataracts (Fig 3B) developed in 12% of patients, ranging from 3% in patients without acute and chronic GVHD to 27% in patients with both acute and chronic GVHD. As shown previously, in patients not exposed to TBI, cataracts occurred exclusively in patients receiving steroids for the treatment of GVHD.28,29 Restrictive or obstructive pulmonary disease (Fig 3C) developed in 24% of patients, ranging from 13% in patients who never had GVHD to 45% in patients with de novo chronic GVHD, ie, in patients who had not received immunosuppressive treatment other than GVHD prophylaxis early posttransplant. The case fatality rate was 17%. One additional patient is surviving 2 years after a lung transplant. Aseptic necrosis (requiring joint replacement in 11 patients) or severe osteoporosis (Fig 3D) occurred in 18% of patients, ranging from 0.1% in patients with acute, but no chronic GVHD, to 22% in patients with both acute and chronic GVHD. Eleven posttransplant solid tumor malignancies were observed (12%) (Fig 3E). The probability was highest (30% at 20 years) in patients with both acute and chronic GVHD and lowest (0%) in patients with prior acute, but without chronic GVHD. Ten neoplasms were squamous cell carcinomas of skin or mucous membranes and one was an adenocarcinoma of the cervix.30 As reported previously,31 carcinomas of the oropharyngeal mucosa occurred exclusively in patients with chronic GVHD. Carcinomas of the skin were seen in patients with or without GVHD. Three patients died of progressive disease and eight are surviving after surgery. Nineteen percent of patients experienced depression requiring therapy, or attempted suicide (one successful) (Fig 3F), with a probability ranging from 0% in patients with acute, but no chronic GVHD, to 38% in patients with both acute and chronic GVHD.

Cumulative incidence of delayed complications dependent on acute and chronic GVHD. (A) Skin disease; (B) cataracts; (C) lung disease; (D) bone and joint disease; (E) posttransplant malignancy; (F) depression. For any patient, only the first event was considered. While only 2-year survivors were included in the analysis, the onset of a given complication could have been before the 2-year mark. A, acute GVHD; C, chronic GVHD; “+”, present; “—”, absent

Cumulative incidence of delayed complications dependent on acute and chronic GVHD. (A) Skin disease; (B) cataracts; (C) lung disease; (D) bone and joint disease; (E) posttransplant malignancy; (F) depression. For any patient, only the first event was considered. While only 2-year survivors were included in the analysis, the onset of a given complication could have been before the 2-year mark. A, acute GVHD; C, chronic GVHD; “+”, present; “—”, absent

Pregnancy.

At 20 years posttransplant, the probability that a female patient would become pregnant was 47% (ranging from 26% in patients with acute and chronic GVHD to 61% in patients with de novo chronic GVHD) and the probability that a male patient had fathered a child was 50% (ranging from 29% in those with acute and chronic GVHD to 62% among patients with neither acute nor chronic GVHD). It was not possible to determine precisely what proportion of patients had attempted to have children. These results have been reported in detail previously.25

School and employment.

At 2 years, 83% of patients had returned to school or work; by 5 to 20 years, this proportion had increased to 86% to 90%. Among patients less than 18 years old at transplant, 95% and 91% without and with chronic GVHD had returned to school/employment, compared with 86% and 77%, respectively, for patients 18 years or older. None of these differences were statistically significant.

Causes of death.

Among patients without chronic GVHD, 4 died of miscellaneous causes (Table 4). Among patients with chronic GVHD, 13 have died (Table 4). Among those transplanted in 1970 to 1977 (n = 16) no late deaths occurred until 13 years after transplantation; subsequent deaths were related to squamous cell carcinoma (n = 2), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (n = 1), and pulmonary failure (n = 1). In patients transplanted in 1978 to 1984 (n = 39), deaths occurred earlier and were generally related to pulmonary failure and infection (n = 8). In the cohort transplanted in 1985 to 1992 (n = 31), 1 patient died of pulmonary failure.

Patient self-assessment.

Beginning in 1990, patients were also mailed questionnaires requesting self-assessment. These questionnaires were sent to all surviving patients regardless of the posttransplant interval. At least one questionnaire was completed by 164 patients, and 77 patients completed two. Compliance was highest for patients transplanted in early years and decreased among patients transplanted more recently (Table 5). As shown in Table5, compliance was not different in patients with and patients without chronic GVHD.

Results of self-assessment of physical, social and mental health, and severity of symptoms are summarized in Table 5. Among these 2-year survivors, no significant differences over time posttransplant were observed for any individual parameter. There was a suggestion that chronic GVHD had a significant effect (P = .07 at ≥10 years) and that age ≥18 years increased the severity of symptoms (P< .001) at the 5-year point, but not subsequently. In other words, patients who had survived at least 2 years posttransplant remained rather stable over more than 2 decades of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

To provide a long-term perspective of treatment results, we evaluated the outcome in patients with aplastic anemia transplanted at the FHCRC and surviving ≥2 years posttransplant. With follow-up reaching to 26 years, these patients have an excellent life expectancy and most are doing well. Chronic GVHD, which had developed in 41% of patients, was the most frequent late event31,32 and had an impact on survival: 89% of patients without chronic GVHD were projected to survive at 20 years, compared with 69% for those with chronic GVHD. Thirteen of 17 patients who died at 2.5 to 20.4 years had chronic GVHD; none of the four late deaths in patients without chronic GVHD was directly transplant-related. Risk factors for chronic GVHD were those recognized in earlier studies, ie, acute GVHD, infusion of viable donor buffy coat cells, and older patient age.33 The omission of buffy coat infusion has significantly reduced the incidence of chronic GVHD.11 ATG as part of the conditioning regimen may be associated with less chronic GVHD,11 an observation similar to that in patients given Campath 1 antibody before transplantation from an unrelated donor.34 Improved supportive care in recent years appears to have increased survival by reducing mortality in the first 2 years posttransplant.31 Interestingly, patients transplanted before 1978 who developed chronic GVHD and survived 2 years were as likely to survive as patients without chronic GVHD, presumably because those with the most severe problems died early, ie, before 2 years.

Chronic GVHD emerged as a risk factor for nearly all long-term complications. Aside from a direct involvement of target organs by GVHD (skin, lungs), treatment of GVHD, especially with steroids, enhanced the likelihood of delayed complications such as cataracts or musculoskeletal disease.21,24,35 In fact, cataracts and aseptic necrosis occurred exclusively in patients who had received glucocorticoids. On the other hand, pulmonary problems were most frequent in patients with de novo chronic GVHD. This observation suggests the possibility that late institution of GVHD therapy in patients who never had clinically apparent acute GVHD allowed for the development of pulmonary pathology.32,36 Posttransplant malignancies developed in 11 patients, five with and six without chronic GVHD. In two patients, the underlying diagnosis was Fanconi anemia. Although no significant risk factor for the development of a posttransplant malignancy was identified in the present analysis, in a recent study of 700 patients with aplastic anemia, treatment of chronic GVHD with azathioprine emerged as a significant risk factor.30

We have shown previously that patients with aplastic anemia conditioned for transplantation with a nonirradiation regimen were likely to preserve their ability to become pregnant or father normal children.25 This finding was confirmed in the present analysis, although it is unknown how many of the patients attempted to have children. It is also not clear why transplantation in more recent years was associated with a higher likelihood of posttransplant pregnancy.

We also attempted to evaluate the patients' current status by means of self-assessment questionnaires.24 In agreement with at least one other report,35 neither time from transplant nor the presence of chronic GVHD had a significant impact on the patients' self-assessment score, although there was a trend for patients with chronic GVHD and for older patients to score lower than patients without GVHD and younger patients. A negative effect of age on posttransplant assessment was observed by Schmidt et al37 and by Baker et al38 and was thought to be related to an increase in chronic GVHD incidence with age. Regardless of GVHD, however, patients generally assessed their quality of life as excellent. By 2 years posttransplant, 83% of patients were employed or had returned to school; this proportion had increased to 86% to 90% by 15 to 20 years. These numbers compare favorably with the 55% to 65% employment reported for allogeneic transplant recipients treated for various malignant diseases39,40 and are similar to those in autologous transplant recipients.41

The present analysis confirms that marrow transplantation offers effective therapy for patients with aplastic anemia. Most patients who survived for at least 2 years posttransplant returned to a productive life. The likelihood was higher in patients without chronic GVHD. The probability of being well and returning to a functionally satisfactory lifestyle was somewhat better than reported for patients transplanted for a malignant disorder.39,40 At last follow-up, all patients had normal hematopoiesis derived from donor cells, providing proof that small numbers of stem cells allow for long-term effective hematopoiesis. In contrast to patients given immunosuppressive therapy,42-45 none of the transplanted patients developed a new hematologic disorder. While some posttransplant malignancies developed, most were treated successfully; only three patients, all of whom had chronic GVHD, died. A large proportion of both female and male patients preserved (or gained) the ability to have children. The overall self-assessment of patients indicated an excellent level of satisfaction and reintegration into societal networks. Efforts must be directed at the prevention and efficient therapy of chronic GVHD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank all patients and their physicians and nurses who have continued to provide us with follow-up information for as long as 26 years. We appreciate the efforts of the staff in the Long-Term Follow-Up Department, in particular Kathy Erne, Muriel Siadak, Judy Campbell, Deborah Monroe, and Marianne Hansen. We thank Bonnie Larson and Harriet Childs for typing the manuscript.

Supported in part by Public Health Service Grants No. HL36444, CA18221, CA15704, and by contract N01 CP51027 awarded by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, MD. H.J.D. is also supported by a grant from the National Marrow Donor Program (Minneapolis/St Paul, MN).

Address reprint requests to H. Joachim Deeg, MD, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue N, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.