Abstract

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulates the proliferation and restricted differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors into neutrophils. To clarify the effects of G-CSF on hematopoietic progenitors, we generated transgenic (Tg) mice that had ubiquitous expression of the human G-CSF receptor (hG-CSFR). In clonal cultures of bone marrow and spleen cells obtained from these mice, hG-CSF supported the growth of myelocytic as well as megakaryocytic, mast cell, mixed, and blast cell colonies. Single-cell cultures of lineage-negative (Lin−)c-Kit+Sca-1+ or Sca-1− cells obtained from the Tg mice confirmed the direct effects of hG-CSF on the proliferation and differentiation of various progenitors. hG-CSF also had stimulatory effects on the formation of blast cell colonies in cultures using 5-fluorouracil–resistant hematopoietic progenitors and clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ primitive hematopoietic cells. These colonies contained different progenitors in proportions similar to those obtained when mouse interleukin-3 was used in place of hG-CSF. Administration of hG-CSF to Tg mice led to significant increases in spleen colony-forming and mixed/blast cell colony-forming cells in bone marrow and spleen, but did not alter the proportion of myeloid progenitors in total clonogenic cells. These results show that, when functional G-CSFR is present on the cell surface, hG-CSF stimulates the development of primitive multipotential progenitors both in vitro and in vivo, but does not induce exclusive commitment to the myeloid lineage.

MULTIPOTENTIAL hematopoietic stem cells give rise to committed cells that undergo terminal differentiation in various lineages. Although it is widely accepted that these multistage developmental processes are supported by cytokines,1 the mechanism governing the commitment of multipotential progenitors remains unclear. To date, several investigators have proposed two opposing models for this process. In the deterministic model, the commitment of multipotential progenitors is determined by exogenous stimuli such as cytokine receptor signals.2 In the stochastic model, spontaneous random events result in the commitment of progenitors whose survival is supported by cytokines.1

Hematopoietic progenitors express various cytokine receptors. Cytokines exert their biological effects by binding to specific, high-affinity receptors. If the commitment of hematopoietic cells occurs according to the deterministic model, signal transduction mediated by a lineage-restricted cytokine receptor expressed by a hematopoietic progenitor is a key inductive event. Forced expression of such a receptor by primitive hematopoietic cells would promote differentiation to a particular lineage. To test this model, we generated transgenic (Tg) mice expressing the human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (hGM-CSFR).3 In hGM-CSFR-Tg mice, hGM-CSF stimulated myelopoiesis as well as the development of cells of various other lineages. Similar results were reported by Takagi et al4 in Tg mice expressing the mouse interleukin-5 receptor α subunit (mIL-5Rα). To examine whether the findings obtained in the hGM-CSFR and mIL-5Rα-Tg mice are universally applicable to other cytokines, expression of more specific signal-transducing receptors by mature progenitors is needed. Because the effects of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and expression of its receptor are normally limited to cells of myeloid lineage, we selected the hG-CSFR for expression as a transgene in mice.

hG-CSF is a glycoprotein synthesized by a variety of cell types.5-7 Several in vitro studies have shown that G-CSF is capable of activating mature neutrophils and supporting the proliferation and myeloid differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells in both mice and humans, indicating that the potential of G-CSF is restricted to the myeloid lineage.5,7,8 The effects of G-CSF are mediated by binding to its specific receptor (G-CSFR), which belongs to a superfamily of cytokine/hematopoietic receptors.9 The expression of the G-CSFR by murine hematopoietic progenitors has not been extensively analyzed. However, in binding studies using radiolabeled G-CSF, the G-CSFR was found on murine granulocytic cells from myeloblasts to mature neutrophils, as well as a subset of monocytes, but not on erythroid cells or megakaryocytes.10

hG-CSFR-Tg mice were generated by standard oocyte injection.11 hG-CSF supported the growth of multipotential hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR obtained from these mice both in vitro and in vivo, but did not alter their commitment program. These results are consistent with the stochastic rather than the deterministic model of hematopoietic differentiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hematopoietic growth factors and antibodies.

Recombinant hG-CSF, human erythropoietin (hEPO), recombinant mouse stem cell factor (mSCF), and human thrombopoietin (hTPO) were kindly provided by Kirin Brewery (Tokyo, Japan). Mouse IL-3 (mIL-3) was from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA). Recombinant hIL-6 was kindly provided by Tosoh Co (Kanagawa, Japan). All cytokines were pure recombinant molecules and were used at concentrations that induced an optimal response in methylcellulose culture of murine hematopoietic cells. These concentrations are 20 ng/mL for hG-CSF, 10 ng/mL for mIL-3, 2 U/mL for hEPO, 20 ng/mL for hTPO, 100 ng/mL for hIL-6, and 100 ng/mL for mSCF. Allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti–c-Kit antibody (ACK-2) was kindly provided by Dr Shin-Ichi Nishikawa (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan). Biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) specific for CD45R (B220, RA3-6B2), Gr-1 (Ly-6G, RB6-8C5), CD4 (L3T4, RM4-5), CD8a (Ly-2, 53-6.7), TR119 (erythroid cells, TER119), Mac-1 (CD11b, M1/70), and LMM741 (a mouse anti–hG-CSFR MoAb) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antimouse Sca-1 (Ly-6A/E, E13-161.7), APC-conjugated rat IgG2b, and rat antimouse CD32/CD16 (FcγII/III receptor, 2.4G2) were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated streptavidin, rat IgG2a, Texas red (TR)-conjugated streptavidin, and R-PE-cyanine 5–conjugated streptavidin (RPE-Cy5-SA) were purchased from Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems (San Jose, CA), Cedarlane Laboratories, Ltd (Hornby, Canada), Life Technologies, Inc (Gaithersburg, MD), and DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark), respectively.

Construction of hG-CSFR cDNA and generation of Tg mice.

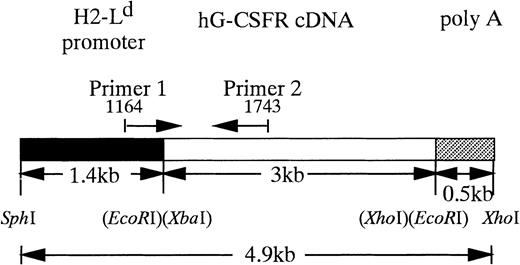

The 3-kb fragment of hG-CSFR cDNA9 was inserted into theEcoRI site of a pLG1 expression vector that has a 1.4-kb mouse major histocompatibility complex (MHC) L-locus gene (H2-Ld) promoter (Fig 1). The 0.5-kb β-globin polyadenylation sequence was placed downstream of these sites. The resulting pLd-hG-CSFR plasmid was 8.5 kb. pLd-hG-CSFR was digested with restriction enzymesSph I and Xho I, and the restriction fragment containing the hG-CSFR insert was separated from the vector by low-melting agarose gel (Sea Plaque; FMC Bio Products, Rockland, ME). DNA fragments, purified using a QIAGEN tip 5 column (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany), were dissolved in 10 mmol Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 0.2 mmol EDTA. Tg mice were produced by standard oocyte injection11 using the C3H/HeN strain. The mice were maintained in an environmentally controlled clean room with 12-hour light-dark cycles under specific pathogen-free conditions in micro-isolator cages. Tg mice were screened for successful integration of hG-CSFR by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Southern blot analysis of tail DNA, using a hG-CSFR cDNA fragment as a probe. Mouse tail-tip DNA was prepared by the removal of 1 cm of tail, which was incubated in 0.7 mL of tail-tip buffer (50 mmol Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.1 mmol EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.02 mg/mL proteinase K) at 55°C for 15 hours. The lysate was extracted with an equal volume of phenol and chloroform. PCR was performed using 1 μg of total genomic DNA, 20 pmol of primers, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin Elmer Cetus, Foster City, CA) for 30 cycles (94°C for 30 seconds, 62°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 2 minutes), followed by 7 minutes at 72°C using a DNA thermocycler (GeneAmp, PCR System 2400; Perkin Elmer). The 5′ primer (P1: 5′GTGCTGGTTATTGTGCTGTC3′) was in the H2-Ldpromoter gene, and the 3′ primer (P2: 5′CGGAGTACTTGGAGTGTTGG3′) was in the hG-CSFR gene (Fig 1). Twenty-five microliters of the amplified solution was run in a 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis in TBE buffer and stained with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. Ten micrograms of mouse genomic DNA was digested withBamHI, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and then transferred to positively charged Nylon Membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) by a capillary system in alkali. The membranes were hybridized with a partial length (900 bp) probe of hG-CSFR cDNA, as described by Sambrook et al.12

Structure of hG-CSFR transgene. Restriction endonuclease cleavage maps of hG-CSFR and pLG1 constructs were used to generate hG-CSFR-Tg mice. Fragments derived from the H2-Ld promoter, the hG-CSFR cDNA, and the poly A addition site of SV40 early gene are shown.

Structure of hG-CSFR transgene. Restriction endonuclease cleavage maps of hG-CSFR and pLG1 constructs were used to generate hG-CSFR-Tg mice. Fragments derived from the H2-Ld promoter, the hG-CSFR cDNA, and the poly A addition site of SV40 early gene are shown.

Reverse transcription-PCR.

The expression of transgene RNA transcripts in different tissues was determined by RT-PCR, using oligonucleotides of hG-CSFR (sense, nucleotide positions 1790 to 1810; antisense, 2159 to 2179) and β-actin (as a positive control; upstream, 5′GTGGGCCGCTCTAGGCACCAA3′; downstream, 5′CTCTTTGATGTCACGCACGATTTC3′) as primers. Total RNA was isolated from bone marrow (BM), peripheral blood (PB), spleen, thymus, liver, heart, intestine, brain, and kidneys of adult (8-week-old) Tg mice by the acid-guanidinium-phenol-chloroform protocol, as described.13 One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed for 1 hour at 37°C using T-Primed First-Strand Kit (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed under the conditions of 35 cycles (94°C for 1 minute, 55°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds), followed by 7 minutes at 72°C using a DNA thermocycler (GeneAmp, PCR System 2400; Perkin Elmer).

Cell preparation.

BM cells from 8-week-old Tg mice and their normal littermates were flushed from femurs and tibiae into minimum essential medium (α-MEM; Flow Laboratories, Rockville, MD) with 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT) using a 26-gauge needle. Spleen cells were obtained by rubbing between two pieces of glasses and repeated pipetting. Cells were then passed through a 70-μm nylon cell strainer (#2350; Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ). PB was collected from an ether-anesthetized mouse by cardiac puncture using a 1-mL syringe and a 21-gauge needle. After collection, PB was quickly mixed with 2 mg EDTA to avoid aggregation. BM mononuclear cells (MNC) were prepared using a density gradient centrifugation method. Cells were diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), layered over Lympholyte-M (Cosmo Bio, Tokyo, Japan), and centrifuged for 30 minutes at 1,500 rpm at room temperature. Interface cells were washed twice with PBS. For experiments involving 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) treatment, 150 mg/kg of 5-FU (5FU; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) was administered by tail vein, and BM cells were harvested 48 hours later. In other experiments, 0.2 mL of PBS, with or without 1,000 μg/kg/d of hG-CSF, was injected intraperitoneally for 7 consecutive days at 9:00 am and 9:00pm. BM and spleen cells were harvested 12 hours after the last injection.

Clonal cell culture.

Clonal cell culture was performed in triplicate as described.14 Briefly, 1 mL of culture mixture containing cells (either 2.5 × 104 BM cells or 2.5 × 105 spleen cells from untreated mice, or 1 × 105 BM cells from 5-FU–treated mice), α-MEM, 1.2% methylcellulose (Shinetsu Chemical, Tokyo, Japan), 30% FBS, 1% deionized fraction V bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemical), 10−4 mol mercaptoethanol (Eastman Organic Chemicals, Rochester, NY), and various combinations of hematopoietic growth factors were plated in each of 35-mm suspension culture dishes (#171099; Nunc, Inc, Naperville, IL) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere flushed with 5% CO2 in air. Except for megakaryocyte colonies, cell aggregates consisting of more than 50 cells were scored as colonies. Colony types were determined on days 7 through 14 of incubation by in situ observation using an inverted microscope, according to the criteria of Nakahata and Ogawa.14,15 Megakaryocyte colonies were scored as such when they had four or more megakaryocytes.16 Abbreviations for the colony types are as follows: GM, granulocyte-macrophage colonies; Mk, megakaryocyte colonies; Mast, mast cell colonies; B, erythroid bursts; Mix, mixed hematopoietic colonies, including GMM (granulocyte-macrophage-megakaryocyte colonies), GEM (granulocyte-erythrocyte-macrophage colonies), and GEMM (granulocyte-erythrocyte-macrophage-megakaryocyte colonies); and Blast, blast cell colonies. To assess the accuracy of in situ identification of colonies, individual colonies were taken with an Eppendorf micropipette under direct microscopic visualization and spread on glass slides using a cytocentrifuge (Cytospin 2; Shandon Inc, Pittsburgh, PA). Slides were then stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa, acetylcholine esterase for megakaryocytes,17 and alcian blue-safranin for mast cells.18

Flow cytometric analysis.

Flow cytometry was performed using a modification of the previously described method.19 Briefly, after depletion of erythrocytes with Lysing Solution (Nichirei Co, Tokyo, Japan), 5 × 105 BM, spleen, and PB cells were suspended with 100 μL of staining buffer (PBS containing 2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide). Cells were incubated with biotin-conjugated LMM741 for 30 minutes on ice, followed by an incubation with RPE-Cy5–conjugated streptavidin for 30 minutes on ice. Antibodies were incubated with cells for 30 minutes on ice for all cases. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).

Clone-sorting and single-cell culture.

Clone-sorting of lineage-negative (Lin−)c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells from BM cells of (C57BL/6 × C3H/HeN) F1 Tg mice and their littermates was performed using a modification of a reported technique.20 Briefly, BMMNC were enriched by negative selection with streptavidin-conjugated beads (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA) using a cocktail of biotin-conjugated MoAbs specific for CD45R/B220, Gr-1, CD4, CD8, TR119, and Mac-1. After incubation with rat antimouse CD32/CD16 to avoid nonspecific antibody binding, the lineage marker-negative cells were stained with PE-conjugated Sca-1 and APC-conjugated anti-c-Kit antibody (ACK-2). The cells were then washed twice and incubated with TR-conjugated streptavidin. The negative controls were cells stained with PE-conjugated rat IgG2a, APC-conjugated rat IgG2b, or only TR-conjugated streptavidin. Based on these controls, individual Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells were sorted into each well of 96-well flat-bottomed plates (#163320; Nunc) with a FACSVantage equipped with an automatic cell deposition unit (ACDU; Becton Dickinson). The clone-sorted cells were cultured in each well containing 200 μL culture medium containing 30% FBS, 1% deionized fraction V BSA, 10−4 mol mercaptoethanol, and 20 ng/mL hG-CSF or 10 ng/mL mIL-3 in α-MEM. The cultures were incubated for 8 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. On days 5 and 8 of culture, colony formation was observed and classified using an inverted microscope. To confirm colony types, each colony was lifted from the medium on day 8, spread on glass slides using a cytocentrifuge (Cytospin 2; Shandon Inc), and stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa.

Replating experiment.

Blast colonies derived from BM cells of 5-FU–treated mice in clonal culture and sorted hematopoietic progenitors in suspension culture were recultured to analyze the hematopoietic capability of the constituent cells.21 On day 7 of culture, blast colonies in clonal culture were individually taken from methylcellulose medium with a 3-μL Eppendorf micropipette under an inverted microscope and suspended in 200 μL of α-MEM. After gentle pipetting, the samples were equally divided into two aliquots: 100 μL was replated in secondary methylcellulose culture supplemented with mIL-3, mSCF, hIL-6, hTPO, and hEPO for hematopoietic progenitor assay, and the remaining 100 μL was used for cytospin preparations stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa to confirm their blastic character. Blast colonies generated in suspension culture of clone-sorted cells were processed similarly. The secondary cultures were incubated under the conditions described above for an additional 8 days, and colonies produced were scored in the same manner as the primary culture.

Assay for spleen colony-forming units.

The assay for spleen colony-forming unit (CFU-S) was performed using a modification of the method of Till et al.22 Cell suspensions derived from hG-CSF– or PBS-treated Tg mice and littermates were injected into C3H/HeN mice exposed to 9.2 Gy of total irradiation from 60Co source at a dose rate of 1.0 Gy/min via tail vein. Eight and 12 days after the injection, the recipients were killed, their spleens were fixed in Bouin’s solution, and macroscopic colonies were counted under a microdissection microscope (day-8 and day-12 CFU-S). Experimental groups were compared with corresponding control groups (irradiation without cell injection). No more than one colony was found in any irradiated control group of mice.

RESULTS

Establishment of hG-CSFR Tg mice.

To express hG-CSFR cDNA in Tg mice, we used the H2-Ld-pLG1 vector consisting of 1.4 kb of the 5′-flanking sequence from the MHC class I H2-Ld gene and 0.5 kb of polyadenylation site from the rabbit β-globin gene. The H2-Ld promoter was chosen to obtain ubiquitous expression of the transgene.23hG-CSFR cDNA was inserted into the EcoRI site of the pLG1 expression vector to generate the pLd-hG-CSFR construct (Fig 1). Expression of the construct was verified by flow cytometry using hG-CSFR–transfected COS7 monkey kidney cells. The results of flow cytometry indicated that expression of protein products was from the pLd-hG-CSFR construct (data not shown). To generate Tg mice, the 4.9-kb Sph I-Xho I DNA fragment containing the hG-CSFR and the H2-Ld promoter was injected into fertilized (C3H/HeN) eggs, which were then transferred into the oviducts of pseudopregnant females. To screen the Tg mice, tail DNA was analyzed by PCR with oligonucleotide primers, P1 and P2 (Fig1). Size and copy numbers of the transgene were then confirmed by Southern blot analysis using the entire hG-CSFR cDNA as a probe (data not shown). Five of 17 founder offspring were found to carry the hG-CSFR transgene.

Expression of hG-CSFR in Tg mice.

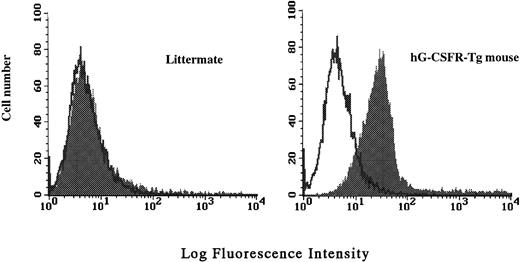

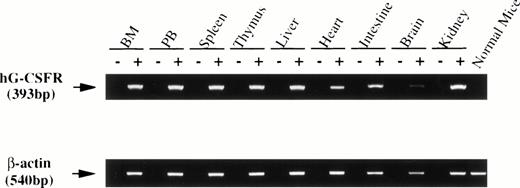

Surface expression of the hG-CSFR transgene product in hematopoietic cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using LMM741. Two of five lines carrying hG-CSFR cDNA, designated lines #70 and #85, expressed hG-CSFR on the surface of BM, spleen, and PB cells. Figure 2 shows the expression of hG-CSFR on BM cells from a Tg mouse of line #70, which was used for subsequent experiments. Normal littermates served as negative controls in all experiments. The H2-Ld-hG-CSFR construct was designed to produce ubiquitous expression of transgene RNA products in the Tg mice. RT-PCR was performed to examine expression of the transgene RNA transcripts in various tissues of Tg mice from line #70. RT-PCR products of 393 bp were obtained from BM, PB, spleen, thymus, liver, heart, intestine, brain, and kidney (Fig 3). Transgene expression was practically at the same level in male and female Tg mice from line #70 (data not shown). No remarkable differences in the number of white blood cells, red blood cells, reticulocytes, platelets, and the levels of hemoglobin were found between Tg mice and littermates from line #70 (data not shown).

Cell surface expression of hG-CSFR on total BM cells analyzed by flow cytometry. BM cells of a hG-CSFR-Tg mouse in line #70 and a littermate used as negative control were stained with biotin-conjugated LMM741 followed by RPE-Cy5–conjugated streptavidin. Fluorescence intensity of staining is plotted against relative cell number.

Cell surface expression of hG-CSFR on total BM cells analyzed by flow cytometry. BM cells of a hG-CSFR-Tg mouse in line #70 and a littermate used as negative control were stained with biotin-conjugated LMM741 followed by RPE-Cy5–conjugated streptavidin. Fluorescence intensity of staining is plotted against relative cell number.

RT-PCR analysis of transgene expression. RNA was prepared from various tissues of hG-CSFR-Tg mice in line #70. cDNA derived from 1 μg total RNA was used for PCR. The lane marked (−) is the PCR product of a mock cDNA (no reverse transcriptase included in the cDNA synthesis reaction). Normal mouse indicates the PCR product of the bone marrow. PCR was performed for 30 cycles. Expression of the hG-CSFR transgene was observed in BM, PB, spleen, thymus, liver, heart, intestine, brain, and kidney.

RT-PCR analysis of transgene expression. RNA was prepared from various tissues of hG-CSFR-Tg mice in line #70. cDNA derived from 1 μg total RNA was used for PCR. The lane marked (−) is the PCR product of a mock cDNA (no reverse transcriptase included in the cDNA synthesis reaction). Normal mouse indicates the PCR product of the bone marrow. PCR was performed for 30 cycles. Expression of the hG-CSFR transgene was observed in BM, PB, spleen, thymus, liver, heart, intestine, brain, and kidney.

Colony formation from BM cells of hG-CSFR Tg mice.

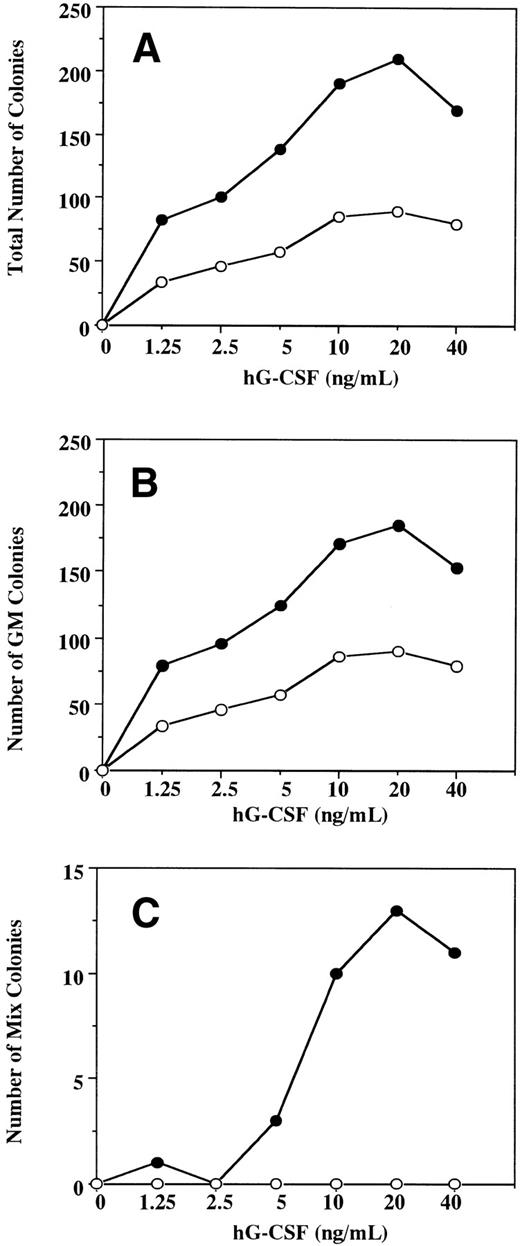

To examine the effect in vitro of hG-CSF on murine hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR, we performed methylcellulose clonal cultures using BM cells obtained from Tg mice and littermates (Table 1). In normal littermates, hG-CSF supported formation of GM but not other types of colonies from BM cells and showed no burst-promoting activity in the presence of EPO. The formation of GM colonies in response to hG-CSF suggests that hG-CSF has cross-species activity with murine BM cells, in accordance with previous studies.24 25 In Tg mice, hG-CSF supported the formation of greater numbers of GM colonies than in normal littermates. hG-CSF also supported the formation of Mk and mast cell colonies and promoted erythroid burst formation. In addition, hG-CSF alone supported the formation of a substantial number of Mix and blast colonies from BM cells. These observations indicate that, when the hG-CSFR is expressed by hematopoietic progenitors, hG-CSF can stimulate the proliferation not only of myelocytic, but also erythroid, megakaryocytic, mast cell, and multipotential hematopoietic progenitors. To confirm the effects of hG-CSF on colony formation from hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR, BM cells from Tg mice and littermates were cultured in the presence of varying concentrations of hG-CSF. In littermates, hG-CSF supported the dose-dependent formation of GM colonies (Fig 4A and B) with a maximal effect at 20 ng/mL. No Mix or blast colony formation was observed at concentrations of up to 500 ng/mL of hG-CSF (Fig 4C and data not shown). In Tg mice, hG-CSF stimulated total colony formation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 4A). The response to hG-CSF in GM colony formation showed a pattern similar to that seen in littermates. However, the total number of GM colonies was higher for any given concentration of hG-CSF (Fig4B). Mix and blast colonies were also formed in a dose-dependent manner, reaching a plateau at 20 ng/mL of hG-CSF (Fig 4C).

A dose-response study for the effect of hG-CSF on the formation of total (A), GM (B), and mix/blast colonies (C) by 1 × 105 BM cells of hG-CSFR-Tg mouse (•) and littermate (○). Representative data from the two separate experiments are shown.

A dose-response study for the effect of hG-CSF on the formation of total (A), GM (B), and mix/blast colonies (C) by 1 × 105 BM cells of hG-CSFR-Tg mouse (•) and littermate (○). Representative data from the two separate experiments are shown.

Colony formation from BM cells of 5-FU–treated mice.

To investigate in detail the effects of hG-CSF on multipotential hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR, we cultured BM cells from 5-FU–treated Tg mice and littermates in the presence of hG-CSF or mIL-3 (Table 2). In littermates, hG-CSF did not induce the formation of any colonies. In contrast, mIL-3 supported the formation of GM, Mix, and blast colonies. In Tg mice, both hG-CSF and mIL-3 induced the formation of GM, Mk, and Mix colonies. Identical numbers of blast colonies were induced by hG-CSF relative to mIL-3.

We next replated blast colonies induced by hG-CSF or mIL-3 and analyzed their hematopoietic capability. Table 3shows representative results of the replating. When recloned in the secondary culture containing SCF, IL-3, IL-6, EPO, and TPO, blast colonies induced by hG-CSF from BM cells of Tg mice gave rise to erythroid bursts, GM, Mk, mast, Mix, and blast colonies. Expression of hG-CSFR transgene RNA transcripts by these colonies was confirmed by RT-PCR (data not shown). Whereas each blast colony gives rise to a heterogeneous mix of secondary colony types, the distribution of various progenitors in hG-CSF–induced blast cell colonies was practically identical to that induced by mIL-3 in BM cells from 5-FU–treated Tg mice or littermates. Thus, hG-CSF appears to stimulate the proliferation and differentiation of primitive multipotential progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR, but does not affect their commitment to each hematopoietic lineage.

Colony formation from clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+/−cells.

In Tg mice, accessory cells expressing the hG-CSFR may respond to hG-CSF by producing various cytokines that induce proliferation or differentiation of primitive hematopoietic progenitors. To explore this possibility, we clone-sorted BM from Tg mice and littermates to obtain Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells, which have been shown to reflect primitive murine hematopoietic progenitors and more mature populations, respectively.26Single-cell cultures were prepared (Table4). Because it has been reported that only a portion of primitive hematopoietic cells express Sca-1 antigen in C3H/HeN,27 we generated hG-CSFR Tg mice and their littermates whose background was (C57BL/6 × C3H/HeN) F1 and used their BM as a source of sorted cells. mIL-3 supported the formation of various types of colonies, including GM, Mk, mast, and Mix colonies from Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ and Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells. Blast colonies were generated from Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ but not Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells in both Tg mice and littermates. In contrast, hG-CSF supported only GM colony formation from Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells. A few GM colonies were derived from the Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ primitive cell population in littermates. In Tg mice, both hG-CSF and mIL-3 supported the formation of GM, Mk, mast, and Mix colonies, with a high cloning efficiency from both fractions. Interestingly, in the presence of hG-CSF, a significant number of blast colonies were generated from Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells obtained from Tg mice. When replated in secondary culture, these blast colonies produced various types of colonies, including erythroid bursts, and GM, Mk, mast, Mix, and blast colonies. Similar types of colonies were induced by mIL-3 from BM cells of Tg mice and littermates (Table 5). These results indicate that hG-CSF acts directly on hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR and that the effects of hG-CSF were not mediated by accessory cells. This finding further supports the concept that hG-CSF stimulates the development of primitive hematopoietic progenitors, but does not induce exclusive commitment to the myeloid lineage.

Effect of hG-CSF administration to Tg mice.

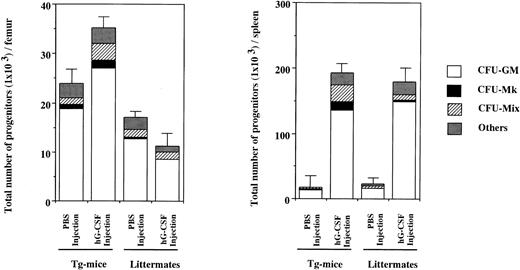

To examine the effect in vivo of hG-CSF on hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR, 1,000 μg/kg of hG-CSF was administered to Tg mice and littermates for 7 days and then CFU-S and clonogenic cells in BM and spleen were evaluated. As shown in Table 6 (experiment no. 1), CFU-S in BM from littermates did not increase with hG-CSF administration, relative to PBS controls. In contrast, 2.9- and 2.2-fold increases were found in day-8 and day-12 CFU-S, respectively, in BM from Tg mice. In the spleen, hG-CSF led to marked increases in CFU-S in Tg mice, with day-8 and day-12 CFU-S increased 18.9- and 20.0-fold, respectively. In littermates, hG-CSF induced a 7.5-fold increase in day-8 CFU-S and a 6.4-fold increase in day-12 CFU-S. Similar results were obtained in experiment no. 2 in Table 6. Figure 5 shows the total numbers of hematopoietic progenitors obtained from the BM and spleen of Tg mice and littermates treated with hG-CSF determined by methylcellulose clonal culture. Whereas the number of hematopoietic progenitors in the BM of littermates was decreased by hG-CSF administration, this treatment increased their numbers in Tg mice. The increased progenitors in Tg mice contained a mix of types, including Mix, blast, Mk, GM colony-forming units (CFU-Mix, CFU-Blast , CFU-Mk, and CFU-GM, respectively), and erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-E). However, the proportion of CFU-GM in total clonogenic cells did not change with hG-CSF administration (78.2% and 77.1% in PBS- and hG-CSF–injected Tg mice, respectively). Hematopoietic progenitors in the spleen increased with hG-CSF administration, with the most significant increase seen in CFU-GM in both Tg mice and littermates. However, the proportion of CFU-GM increased in littermates (71.8% and 83.1% in PBS- and hG-CSF–injected littermates, respectively), but not in Tg mice (74.0% and 70.7% in PBS- and hG-CSF–injected Tg mice, respectively). Similar findings were obtained in another independent experiment. These results indicate that hG-CSF also promotes the development of primitive hematopoietic progenitors in vivo, but does not exclusively induce their differentiation to the myeloid lineage.

Hematopoietic progenitors in BM cells from one femur and one spleen of hG-CSFR-Tg mice and littermates receiving hG-CSF. The numbers of hematopoietic progenitors were assayed by methylcellulose clonal culture. “Others” include erythroid and mast cell progenitors. Representative data from the three separate experiments are shown.

Hematopoietic progenitors in BM cells from one femur and one spleen of hG-CSFR-Tg mice and littermates receiving hG-CSF. The numbers of hematopoietic progenitors were assayed by methylcellulose clonal culture. “Others” include erythroid and mast cell progenitors. Representative data from the three separate experiments are shown.

DISCUSSION

G-CSF is a cytokine that specifically stimulates the differentiation of hematopoietic progenitors to the myeloid lineage through interaction with its receptor on the cells.24 28 In this study, using Tg mice expressing the hG-CSFR, the activity of hG-CSF on multipotential progenitors was extensively analyzed. In vitro stimulatory effects of hG-CSF on multipotential progenitors were confirmed in a dose-response study of hG-CSF, culture of 5-FU–resistant progenitors, and single-cell cultures of clone-sorted hematopoietic progenitors. In particular, a number of Mix and blast colonies were generated from clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells, but not from Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1− cells of Tg mice in the presence of hG-CSF, indicating that the proliferation of primitive multipotential progenitors is directly triggered by hG-CSF and is not mediated by the effects of accessory cells activated by hG-CSF. Furthermore, the effect of hG-CSF on the differentiation of multipotential progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR was examined by recloning experiments of blast colonies supported by hG-CSF from 5-FU–resistant progenitors of Tg mice. The constituent cells of blast colonies contained not only myelocytic progenitors, but also various other types of progenitors, including erythroid, megakaryocytic, mast cell, and multipotential progenitors, with a distribution similar to blast colonies supported by mIL-3. The detection of hG-CSFR transgene RNA transcript in RT-PCR analysis of the secondary colonies suggests that hematopoietic progenitors in the blast colonies were developed upon binding of hG-CSF to the receptor on the cells. These observations indicate that hG-CSF, which normally has activity only in cells of myeloid lineage, as shown in experiments using littermates, does not induce the commitment of multipotential progenitors to myeloid lineage in Tg mice. Rather, hG-CSF supports their differentiation to various lineages.

Similar observations were obtained in previous in vitro studies of murine hematopoietic cells transfected with the mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor29 or EPOR transgene30 and in hGM-CSFR-Tg3 or mIL-5Rα-Tg mice,4 although these studies did not exclude the possibility that their observations might be modified by the effects of accessory cells. In the present study, the noninterference of hG-CSF with the commitment of multipotential progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR was confirmed by the presence of various progenitors in the blast colonies supported by hG-CSF derived from clone-sorted Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells. These results indicate that the differentiation process of multipotential progenitors was not affected by accessory cells. The results obtained in these experiments that use cells artificially expressing cytokine receptors may be artifacts arising from receptor overexpression. However, we have recently shown that, whereas the IL-6R, a ligand-binding subunit of IL-6, is expressed on some human myelocytic progenitors, gp130, a signal-transducing subunit of the IL-6R, is expressed on most human hematopoietic progenitors. Thus, IL-6 acts on only myelocytic progenitors, but the addition of soluble IL-6R to IL-6 activates gp130 resulting in the growth of various progenitors, such as myelocytic, erythroid, megakaryocytic, and multipotential progenitors, in the presence of SCF31,32 or ligand for Flk-2/Flt-3.33 This means that the specificity of IL-6 activity depends on the potential of human hematopoietic progenitors to express the IL-6R. Taken together, these results suggest that cytokines function as proliferation-promoting factors of hematopoietic progenitors expressing their receptors and that cellular differentiation is determined by an intrinsic program, consistent with the stochastic model of lineage commitment.

Indeed, hG-CSF supported only GM colony formation in a dose-dependent manner. No other colony types were formed in littermates with up to 500 ng/mL of hG-CSF. In Tg mice, hG-CSF also supported GM colony formation in a dose-dependent manner similar to that observed in littermates. However, the number of GM colonies supported by hG-CSF in Tg mice in the dose-response study and in single-cell cultures of clone-sorted hematopoietic progenitors was greater than that in littermates. hG-CSF supported GM colony formation from 5-FU–resistant progenitors in Tg mice but not in littermates. In addition, hG-CSF supported the formation of a significant number of GM colonies in Lin−c-Kit+Sca-1+ cells from Tg mice, but only a few GM colonies in littermates. These results suggest that immature myelocytic progenitors may not express the G-CSFR, leading to unresponsiveness to hG-CSF in littermates. In Tg mice, the activity of hG-CSF was not restricted to myeloid lineages. hG-CSF stimulated the proliferation of various types of hematopoietic progenitors, including erythroid, megakaryocytic, mast cell, and multipotential progenitors as well as myelocytic progenitors, in accordance with reported data of hGM-CSFR-Tg mice.3However, unlike the result in hGM-CSFR-Tg mice, we observed no erythroid colony and burst formation without EPO, although hG-CSF did have burst-promoting activity in the presence of EPO. The different effects on erythroid cell maturation may be due to differences in signaling pathways between hG-CSFR and hGM-CSFR.

We also examined the effect of hG-CSF on hematopoiesis in Tg mice in vivo. CFU-S and CFU-Mix/Blast in BM and spleen of Tg mice significantly increased with hG-CSF treatment, demonstrating that hG-CSF stimulates the growth of primitive hematopoietic progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR in vivo. We observed that, although CFU-S and CFU-Mix/Blast decreased in the BM of littermates, they increased in the spleen to a lesser degree than in Tg mice. These increases in the spleen of littermates may be due to migration of progenitors from BM after hG-CSF treatment, in accordance with the report that G-CSF administration to normal mice significantly stimulates mobilization of various hematopoietic progenitors from BM to spleen.34 The observation that the proportion of CFU-GM in total clonogenic cells was not affected by hG-CSF treatment, despite the marked expansion of primitive multipotential progenitors in Tg mice, also indicates that hG-CSF does not induce a shift of differentiation of progenitors expressing the hG-CSFR to the myeloid lineage in vivo.

It is generally held that self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells occurs according to a stochastic rule similar to the differentiation of progenitor cells. Cytokines supporting the development of hematopoietic stem cells have not been found; hence, in vitro culture of transplantable human stem cells has been unsuccessful. On the other hand, whereas expression of cytokine receptors on human hematopoietic stem cells has not been extensively analyzed, we recently found that the hG-CSFR is expressed on myelocytic progenitors, but not primitive hematopoietic stem cells (Ebihara et al, unpublished data). In this context, it is of interest to determine if the activity of hG-CSF observed in the present study is applicable to development of hematopoietic stem cells expressing the hG-CSFR. If it is applicable, hG-CSF could support the development of human stem cells in which the hG-CSFR is artificially expressed, without fear of loss of their stem cell activity. This strategy may possibly open up new molecular approaches to in vitro expansion of transplantable human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank S. Nagata for preparation of hG-CSFR plasmid; I. Nishijima for helpful discussions and technical advice; S. Hanada, I. Hirose, I. Suyama, and K. Sudo for excellent technical assistance; and M. Ohara for comments on the manuscript.

Supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Tatsutoshi Nakahata, MD, PhD, Department of Clinical Oncology, The Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, 4-6-1 Shirokanedai, Minato-ku, Tokyo 108, Japan; e-mail: nakahata@ims.u-tokyo.ac.jp.