Abstract

Fas, a cell surface receptor, can induce apoptosis after cross-linking with its ligand. Fewer than 3% of human thymocytes strongly express Fas. We report that Fas antigen expression can be upregulated by two signaling pathways in vitro, one mediated by anti-CD3 and the other by interleukin-7 + interferon-γ. The two signaling pathways differed in several respects. (1) Fas expression increased in all thymic subsets after cytokine activation, but only in the CD4 lineage after anti-CD3 activation. (2) Fas upregulation was inhibited by cyclosporin A (a calcineurin inhibitor) in anti-CD3–activated but not in cytokine-activated thymocytes. (3) Cycloheximide (a metabolic inhibitor) inhibited Fas upregulation in cytokine-activated thymocytes but not in anti-CD3–activated thymocytes. (4) Cytokine-activated thymocytes were more susceptible than anti-CD3–activated thymocytes to Fas-induced apoptosis, a difference mainly accounted for by CD4+ cells. The nature of the stimulus might thus influence the susceptibility of human thymocytes to Fas-induced apoptosis.

© 1998 by The American Society of Hematology.

Fas (APO-1; CD95) IS A cell surface receptor that is expressed on a variety of tissues. It shows homology with several members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family.1 Its major function appears to be the induction of apoptosis in cells expressing it. Ligation of Fas by its ligand (FasL) or agonistic anti-Fas antibodies induces apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. In the immune system, the role of the Fas/FasL system is well characterized in T-cell cytotoxicity2 and activation-induced cell death of peripheral lymphocytes.3-5

Most mouse thymocytes express Fas and agonistic anti-Fas antibody can induce mouse thymocyte apoptosis in vitro in the presence of additional signals (metabolic inhibitors6 or T-cell receptor [TCR] stimulation7), in thymic organ culture,8 and in vivo.9 The involvement of Fas in thymic negative selection is controversial. In lpr mice, which develop systemic autoimmune disease related to a Fas gene defect,10 and in Fas-null mice, negative selection in response to endogenous superantigens is normal in the thymus, whereas activation-induced cell death of activated peripheral lymphocytes is impaired.11-13 However, Castro et al14 recently reported that thymocytes from lpr mice have reduced susceptibility to TCR-induced apoptosis and that antigen-specific thymocyte deletion in normal mice can be inhibited in vivo by blocking the Fas-FasL interaction. Finally, Kishimoto and Sprent15reported that TCR-CD28–mediated negative selection of mouse HSAhi CD4+CD8− thymocytes in vitro in the presence of high anti-TCR antibody concentrations requires a Fas-dependent pathway.

Few teams have examined Fas expression and function in the human thymus. The normal thymus contains a thymocyte subpopulation strongly expressing Fas (Fashi) and representing 1% to 4% of total thymocytes.16-18 This thymocyte subpopulation may be a target for negative selection and Fas might be involved in the elimination of autoreactive cells, notably because this transitional population contains a large fraction of dead cells16; in addition, an antagonistic anti-Fas antibody inhibits the complete deletion of staphylococcal enterotoxin B-reactive Vβ3-positive human thymocytes.17 We have previously found that Fashi cells accumulate in the thymus of patients with myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disease characterized in 85% of cases by the presence of anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies and associated with thymic abnormalities.18 Fashithymocytes from myasthenia gravis patients were depleted in vitro by an agonistic anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11) and could be involved in the autoimmune response targeting the acetylcholine receptor.

In humans, Fas is expressed by resting peripheral lymphocytes and its expression is upregulated by various cytokines (interferon-γ [IFN-γ] in a human lymphoma cell line19and interleukin-2 [IL-2] in peripheral blood lymphocytes20). In addition, Fas antigen can be induced in vitro by mitogenic stimulation of naı̈ve T and B cells from neonatal blood.21

There are several molecular mechanisms transducing the apoptotic signal after Fas-FasL interaction of Fas and its ligand, but little is known of how the expression of these molecules is regulated or the physiologic function of Fas in in the human thymus. We therefore examined the regulation of Fas expression in human thymocytes in the presence of various stimuli and described two signaling pathways that can lead to Fas expression upregulation, one antigen-dependent and the other cytokine-dependent. These two pathways involve different intracellular mechanisms and lead to different susceptibility to Fas apoptosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thymocyte isolation and culture.

Normal thymus fragments were obtained from infants (age range, 5 days to 2 years) undergoing heart surgery at Marie-Lannelongue Hospital.Thymocytes were mechanically isolated by gently scraping fresh thymic tissue, filtering the cells through sterile gauze, and washing them once in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS).

Ninety-six–well plates were coated with 10 μg/mL mouse anti-CD3 IgG1 antibody (clone 4B5; Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) or 10 μg/mL mouse IgG1 (Dako, Trappes, France) overnight at 4°C. In some experiments, 10 μg/mL anti-CD3 IgG1 antibody and 10 μg/mL anti-CD28 IgG1 antibody (clone CD28.2; Immunotech, Marseille, France) were immobilized on 96-well plates. Isolated thymic cells were cultured in 96-well plates (0.5 × 106 cells in 200 μL) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 25 mmol/L HEPES, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin.

Human thymocytes were cultured in the presence of 1 μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) or the combination of 5 ng/mL phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; Sigma Chemical Co, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) and 500 ng/mL ionomycin (Sigma). The following recombinant human cytokines were also added to thymocytes: IL-2, IL-7, and IFN-γ were from Genzyme Diagnostics (Cergy, France); IL-12 was from Sigma; and IL-6 was from Innotest (Besançon, France). At various culture times, cells were harvested and labeled for Fas expression. Cell recovery and viability were measured by using the Trypan blue exclusion method. In some experiments, thymocytes were cultured with 10 μg/mL cycloheximide (Sigma) or 0.5 μg/mL actinomycin D (Sigma).

Immunofluorescence studies.

Thymocytes were labeled with monoclonal fluorochrome-coupled anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-CD25 antibodies (Immunotech). Three-color flow cytometry was used to examine the relationship between Fas and other markers. Thymocytes were first incubated with anti-Fas (anti-CD95) monoclonal antibody (clone UB2; Immunotech) for 30 minutes at 4°C, then washed twice in HBSS supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, stained with biotin-coupled goat antimouse IgG antibody, washed twice, and incubated with streptavidin, Quantum Red conjugate (Sigma), and membrane fluorescein (FITC)- or phycoerythrin (PE)-coupled antibodies. We checked that the three-color staining gave the same results as one-color staining (anti-CD25) and two-color staining (anti-CD4 and anti-CD8).

Cell labeling was analyzed on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Grenoble, France) using CellQuest software. Ten thousand to 15,000 events were acquired for each sample. A gate was set on freshly isolated thymocytes displaying homogeneous forward- and side-scatter parameters. In this gate, the proportion of dead cells (those incorporating propidium iodide) was always less than 1% whatever the culture time and conditions. All flow cytometer analyses were performed in this gate.

After culture with anti-CD3 or IgG1 antibody, cells were labeled with 20 μg/mL goat antimouse IgG antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc, West Grove, PA) before staining with anti-Fas antibody and then biotin-coupled goat antimouse antibody. This prevented the possible staining of biotin-coupled goat antimouse on anti-CD3 antibody (which was immobilized on 96-well plates and might be fixed on thymocytes during the culture).

Anti-Fas antibody assay.

Thymic cells (105 cells/well) were cultured in 96-well plates with 2 μg/mL anti-Fas IgM antibody (clone CH-11; Upstate Biotechnology Inc, Lake Placid, NY) or 2 μg/mL mouse IgM (Dako) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 25 mmol/L HEPES, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. When indicated, 10 μg/mL cycloheximide was added to the culture. Preliminary kinetic study showed that Fas-induced apoptosis was maximal after 18 hours of incubation with anti-Fas (clone CH-11). Cells were then harvested and apoptosis was analyzed.

Measurement of FITC-conjugated annexin-V binding.

Apoptosis was analyzed by quantifying phosphatidylserine residues exposed on the cell membrane. One microliter of human recombinant FITC-conjugated annexin-V (Boehringer Mannheim) and 2 μg/mL propidium iodide were added to 100 μL of cell suspension in a binding buffer (10 mmol/L HEPES/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L CaCl2). After 15 minutes of incubation in the dark, a dual-color analysis was performed on a FACScan flow cytometer. Specific anti-Fas–mediated apoptosis was calculated by subtracting the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of control IgM from the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11.

In some experiments, thymocytes were first stained with biotin-conjugated anti-CD4 and PE-conjugated anti-CD8. After two washes, cells were incubated with streptavidin, Quantum Red conjugate. After two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), CD4/CD8 staining was analyzed. Thymocytes were then labeled with FITC-conjugated annexin-V. The proportion of annexin-positive thymocytes was examined in the CD4/CD8 subsets. We checked that CD4/CD8 double staining or annexin-V-FITC labeling were not modified in three-color experiments.

After culture with control IgM or anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11), thymocytes were stained with anti-Fas antibody as previously described but with clone CH-11 (instead of clone UB2). Then thymocytes were labeled with FITC-conjugated annexin-V.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between groups were compared by using the Mann-Whitney or Wilcoxon test (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA). A difference was considered significant if the P value was less than .05.

RESULTS

Regulation of Fas expression in human thymocytes by different activation signals.

Freshly isolated thymocytes from 5 infants’ thymuses (age, 7 days to 2 years) were cultured with the following activation factors: immobilized anti-CD3 (mouse IgG1) antibody (10 μg/mL), PHA (1 μg/mL), and the combination of PMA (5 ng/mL), a protein kinase C activator, and ionomycin, a calcium ionophore (500 ng/mL). Control cultures were performed in the absence of stimuli or with immobilized mouse IgG1 (10 μg/mL). Fashi cells represented 0.45% ± 0.08% of freshly isolated cells (means ± SEM, n = 5). Thymocytes were collected after 4, 16, 24, and 48 hours of culture and Fas, CD4, and CD8 expression was examined by using three-color flow cytometry. CD25 expression was also measured to check the level of cell activation.

The ability of anti-CD3 antibody to induce thymocyte death in vitro and the need for a costimulatory signal during TCR stimulation are both controversial.22 23 Human thymocytes cultured for 24 hours were slightly but not significantly depleted by anti-CD3 antibody: when 106 freshly isolated viable thymocytes were cultured, 0.91 ± 0.10 × 106 and 0.81 ± 0.09 × 106 thymocytes were recovered after 24 hours of incubation with immobilized IgG1 and immobilized anti-CD3, respectively (5 independent determinations). The corresponding numbers of viable thymocytes were 0.96 ± 0.10 × 106 in control conditions, 0.91 ± 0.27 × 106 after PHA activation, and 0.68 ± 0.07 × 106 after PMA/ionomycin activation. The cell depletion induced by PMA/ionomycin was not mediated by the Fas system, because it was not prevented by a blocking anti-FasL antibody (clone NOK-1; data not shown).

Kinetic studies showed that CD25 and Fas expression were maximal after, respectively, 16 and 24 hours of activation. Figure 1 shows the result of a representative experiment. PHA weakly activated human thymocytes (measured by CD25 expression) and had no effect on Fas expression. PMA/ionomycin strongly activated thymocytes: 74.5% ± 1.4% of cells expressed CD25 after 16 hours, compared with 1.9% ± 0.2% of cells in control conditions (5 independent determinations). This activation induced a slight increase in Fas expression: 3.3% ± 0.9% of total cells were Fashi after 24 hours of activation with PMA/ionomycin, compared with 1.0% ± 0.2% in control conditions. By contrast, immobilized anti-CD3 antibody moderately increased CD25 expression after 16 hours of incubation (18.6% ± 4.2% of cells v 2.0% ± 0.2% in the presence of mouse IgG1), but enhanced Fas expression (7.0% ± 2.8% of total cells were Fashi after 24 hours of incubation with anti-CD3 antibody v 1.2% ± 0.2% with mouse IgG1). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Fas labeling was also significantly increased to 43.8 ± 4.2 after 24 hours of incubation with anti-CD3 antibody, compared with 33.3 ± 2.9 with mouse IgG1 (P < .05).

Fas expression is differently regulated by activation signals in human thymocytes. Fas and CD25 expression were analyzed after culture with the following activators: immobilized anti-CD3 (mouse IgG, 10 μg/mL), PHA (1 μg/mL), and the combination of PMA (5 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL). Control cultures were performed in the absence of agents or with immobilized mouse IgG1 (10 μg/mL). Thymocytes were collected after 4, 16, 24, and 48 hours of culture and Fas, CD4, and CD8 expression was examined using three-color flow cytometry. CD25 expresssion was also measured to check the level of cell activation. A representative experiment is shown. (A) Analysis of Fas expression after 24 hours of culture with the different activators. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine and anti-CD25 or anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies; only the last two steps were performed in staining controls. Anti-CD3 antibody-activated thymocytes display the higher increase in the Fashi thymocyte proportion and in the MFI of Fas staining. (B) Kinetic study of Fas and CD25 expression on thymocytes cultured with activation factors. CD25 expression was maximal after 16 hours of activation and Fas expression after 24 hours. By contrast with Fas expression, CD25 expression was strongly increased by PMA + ionomycin but moderately increased by anti-CD3 activation.

Fas expression is differently regulated by activation signals in human thymocytes. Fas and CD25 expression were analyzed after culture with the following activators: immobilized anti-CD3 (mouse IgG, 10 μg/mL), PHA (1 μg/mL), and the combination of PMA (5 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL). Control cultures were performed in the absence of agents or with immobilized mouse IgG1 (10 μg/mL). Thymocytes were collected after 4, 16, 24, and 48 hours of culture and Fas, CD4, and CD8 expression was examined using three-color flow cytometry. CD25 expresssion was also measured to check the level of cell activation. A representative experiment is shown. (A) Analysis of Fas expression after 24 hours of culture with the different activators. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine and anti-CD25 or anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies; only the last two steps were performed in staining controls. Anti-CD3 antibody-activated thymocytes display the higher increase in the Fashi thymocyte proportion and in the MFI of Fas staining. (B) Kinetic study of Fas and CD25 expression on thymocytes cultured with activation factors. CD25 expression was maximal after 16 hours of activation and Fas expression after 24 hours. By contrast with Fas expression, CD25 expression was strongly increased by PMA + ionomycin but moderately increased by anti-CD3 activation.

Because CD28 provides a costimulatory signal for TCR stimulation in T lymphocytes24 and for TCR-induced thymocyte apoptosis,23 we examined whether costimulation with immobilized anti-CD28 antibody modulated the anti-CD3–induced increase in the Fashi thymocyte proportion. The number of human thymocytes cultured with anti-CD28 + anti-CD3 antibodies was similar to the number of thymocytes recovered after anti-CD3 activation (not shown). As shown in Table 1, anti-CD28 antibody did not modify the anti-CD3–induced increase in Fas expression in human thymocytes.

Effect of cytokines on Fas expression.

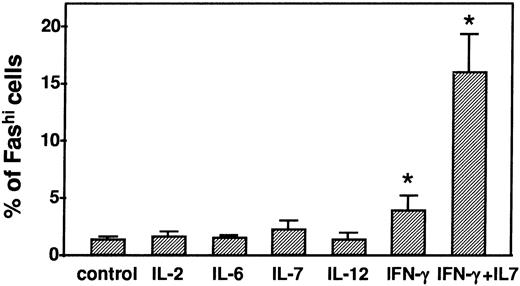

Fas expression in human thymocytes was measured after 24 hours of incubation with IL-2 (200 U/mL), IL-6 (5 pg/mL), IL-7 (10 pg/mL), IL-12 (1 pg/mL), or IFN-γ (500 U/mL). Apart from IFN-γ, none of the cytokines modified Fas expression (Fig 2). IFN-γ slightly but significantly increased the proportion of Fashi thymocytes (4.0% ± 1.2% v1.4% ± 0.1% in control conditions, P < .05). The Fashi cell proportion was strongly increased by the combination of IL-7 and IFN-γ (16.0% ± 3.2% v 1.3% ± 0.2% in control conditions, P < .05). Fas labeling MFI was also significantly increased by IFN-γ and by IL-7 + IFN-γ after 24 hours of incubation (33.0 ± 7.3 and 50.8 ± 8.3, respectively, compared with 24.6 ± 6.5 in control conditions; bothP < .05). The effects of anti-CD3 and IL-7 + IFN-γ on Fas expression were not additive (not shown).

Modulation of the Fashi thymocyte proportion by cytokines. Fas expression in human thymocytes was measured after 24 hours of incubation with IL-2 (200 U/mL), IL-6 (5 pg/mL), IL-7 (10 pg/mL) IL-12 (1 pg/mL), IFN-γ (500 U/mL), or the combination of IL-7 (10 pg/mL) + IFN-γ (500 U/mL). By contrast with the other cytokines, IFN-γ and the combination of IFN-γ + IL-7 significantly increased the Fashi thymocyte proportion. *P < .05 versus control.

Modulation of the Fashi thymocyte proportion by cytokines. Fas expression in human thymocytes was measured after 24 hours of incubation with IL-2 (200 U/mL), IL-6 (5 pg/mL), IL-7 (10 pg/mL) IL-12 (1 pg/mL), IFN-γ (500 U/mL), or the combination of IL-7 (10 pg/mL) + IFN-γ (500 U/mL). By contrast with the other cytokines, IFN-γ and the combination of IFN-γ + IL-7 significantly increased the Fashi thymocyte proportion. *P < .05 versus control.

Activation-induced upregulation of Fas expression in thymic subsets.

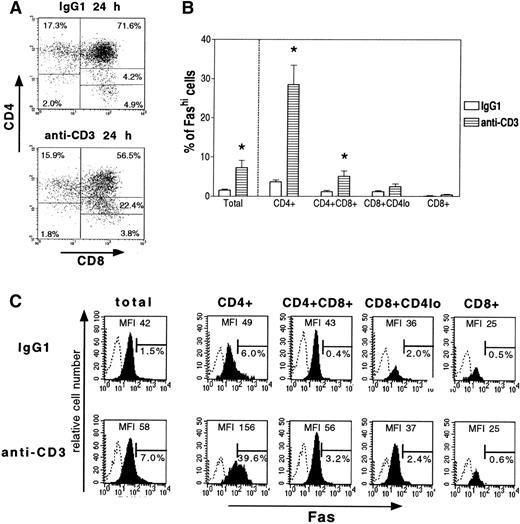

Fas, CD4, and CD8 expression was examined in thymocytes cultured with anti-CD3 antibody or mouse IgG1. After 24 hours of incubation with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody (Fig 3A), there was a significant decrease in the proportion of double-positive CD4+CD8+ thymocytes (47.8% ± 4.5% v 66.9% ± 5.6% in control conditions, P < .05, n = 5) and an increase in the intermediate subset CD8+CD4lo (CD8 with a low expression level of CD4; 28.65 ± 1.9% v 7.2% ± 0.9% in control conditions, P < .05). CD4 modulation by antigenic activation has already been observed in human T-cell clones.25 The proportions of single-positive CD4+ and CD8+cells were not significantly affected (Fig 3A).

Effect of anti-CD3 activation on thymic subsets and their Fas expression. After 24 hours of culture with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody or control IgG1, thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine and anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies; only the last two steps were performed in staining controls. Fas expression was analyzed in total cells and thymic subsets. (A) Representative analysis of CD4 and CD8 expression by thymocytes cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody or IgG1. In comparison with the IgG1 control, anti-CD3 significantly reduced the proportion of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes and increased the intermediate subset CD8+CD4lo. (B) Effect of immobilized anti-CD3 antibody on Fas expression by thymic subsets. Data are means ± SEM of 5 experiments. (C) A representative analysis of total thymocytes and thymic subsets is shown. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. For each stain, the proportion of Fashithymocytes and MFI of Fas staining are indicated. Anti-CD3 significantly increased the Fashi thymocyte proportion among CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ cells but not among CD8+CD4lo or CD8+cells.

Effect of anti-CD3 activation on thymic subsets and their Fas expression. After 24 hours of culture with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody or control IgG1, thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine and anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies; only the last two steps were performed in staining controls. Fas expression was analyzed in total cells and thymic subsets. (A) Representative analysis of CD4 and CD8 expression by thymocytes cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody or IgG1. In comparison with the IgG1 control, anti-CD3 significantly reduced the proportion of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes and increased the intermediate subset CD8+CD4lo. (B) Effect of immobilized anti-CD3 antibody on Fas expression by thymic subsets. Data are means ± SEM of 5 experiments. (C) A representative analysis of total thymocytes and thymic subsets is shown. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. For each stain, the proportion of Fashithymocytes and MFI of Fas staining are indicated. Anti-CD3 significantly increased the Fashi thymocyte proportion among CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ cells but not among CD8+CD4lo or CD8+cells.

We then measured the proportion of Fashi cells in the different subsets (Fig 3B). A representative analysis is shown in Fig3C. The Fashi cell proportion was significantly enhanced by anti-CD3 antibody (7.3% ± 1.8% of total cells v 1.6% ± 0.2% in the presence of IgG1) and especially among CD4+ cells (28.6% ± 4.9% v 3.7% ± 0.5% with IgG1) and CD4+CD8+ (5.1% ± 1.3%v 1.2% ± 0.3% with IgG1). Thus, CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ cells were enriched eightfold and fourfold, respectively, in Fashi cells. The proportion of Fashi cells was very low among CD8+CD4lo and CD8+ cells and was not significantly modified by CD3 activation.

By contrast with antigenic stimulation, stimulation by IL-7 + IFN-γ did not modify the proportion of thymic subsets (not shown) and increased the proportion of Fashi cells in all subsets (Fig 4). A representative analysis is shown in Fig 4B. The proportion of Fashi cells among CD4+, CD4+CD8+, and CD8+ cells increased 8-, 11-, and 11-fold, respectively (Fig 4A).

Effect of IFN-γ + IL-7 on Fas expression in thymic subsets. Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine and anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies; only the last two steps were performed for staining controls. (A) Data are the means ± SEM of 5 experiments. IFN-γ + IL-7 increased the Fashi thymocyte proportion in all the thymic subsets (CD4+, CD4+CD8+, and CD8+ cells). *P < .05 versus control. (□) Medium; (⊟) IL-7 + IFN-γ. (B) Representative analysis of the proportion of Fashi thymocytes and MFI of Fas staining in each culture condition and thymic subset. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles.

Effect of IFN-γ + IL-7 on Fas expression in thymic subsets. Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine and anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies; only the last two steps were performed for staining controls. (A) Data are the means ± SEM of 5 experiments. IFN-γ + IL-7 increased the Fashi thymocyte proportion in all the thymic subsets (CD4+, CD4+CD8+, and CD8+ cells). *P < .05 versus control. (□) Medium; (⊟) IL-7 + IFN-γ. (B) Representative analysis of the proportion of Fashi thymocytes and MFI of Fas staining in each culture condition and thymic subset. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles.

Cyclosporin A inhibits the increase in Fas expression induced by anti-CD3 but not that induced by IL-7 + IFN-γ.

The CD3-induced increase in Fas expression in human thymocytes was examined in the presence of 100 ng/mL cyclosporin A, an immunosuppressive drug known to act on calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin and to inhibit TCR-induced gene expression in T cells.26 After 24 hours of incubation with cyclosporin A, there were no changes in cell viability, the CD4/CD8 subsets, or Fas expression (not shown). The increase in Fas expression induced by anti-CD3 was partially inhibited (∼50%) by cyclosporin A on both CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ cells (Fig 5B). The changes in the proportions of the CD4/CD8 subsets induced by anti-CD3 were also partially inhibited by cyclosporin A (not shown). By contrast, the effect of IL-7 + IFN-γ on the increase in Fas expression was not affected by 100 ng/mL cyclosporin A (Fig 5A).

Effect of cyclosporin A (CsA) on the increase in Fashi cell proportion induced by anti-CD3 antibody or by IFN-γ + IL-7. (A) Representative analysis of Fas expression and Fas staining MFI in human thymocytes activated for 24 hours with anti-CD3 antibody or IFN-γ + IL-7 in the presence of cyclosporin A (100 ng/mL). Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine; only the last two steps were used for staining controls. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. Cyclosporin A partially inhibited the anti-CD3–induced increase in Fas expression but did not modify the increase in Fas expression induced by IFN-γ + IL-7. (B) Effect of cyclosporin A in the different subsets of human thymocytes cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody. Data are the means ± SEM of 3 experiments. Cyclosporin A partially inhibited the increase in the Fashi cell proportion among CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. (□) IgG1; (⊟) anti-CD3; (▪) anti-CD3 + CsA.

Effect of cyclosporin A (CsA) on the increase in Fashi cell proportion induced by anti-CD3 antibody or by IFN-γ + IL-7. (A) Representative analysis of Fas expression and Fas staining MFI in human thymocytes activated for 24 hours with anti-CD3 antibody or IFN-γ + IL-7 in the presence of cyclosporin A (100 ng/mL). Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine; only the last two steps were used for staining controls. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. Cyclosporin A partially inhibited the anti-CD3–induced increase in Fas expression but did not modify the increase in Fas expression induced by IFN-γ + IL-7. (B) Effect of cyclosporin A in the different subsets of human thymocytes cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody. Data are the means ± SEM of 3 experiments. Cyclosporin A partially inhibited the increase in the Fashi cell proportion among CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. (□) IgG1; (⊟) anti-CD3; (▪) anti-CD3 + CsA.

Effect of cycloheximide on the activation-induced increase in Fas expression.

The increase in the Fashi cell proportion induced by anti-CD3 or IL-7 + IFN-γ after 24 hours of incubation was probed with 10 μg/mL cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis (Fig 6). No change in cell viability, Fas expression, or CD4/CD8 subsets was seen after 24 hours of incubation with 10 μg/mL cycloheximide. The effect of IL-7 + IFN-γ on the increase in Fas expression was totally inhibited by cycloheximide (P < .03 compared with thymocytes cultured with cycloheximide alone, n = 5), showing that the increase in Fas expression induced by these cytokines in human thymocytes requires protein synthesis. By contrast, the effect of anti-CD3 was slightly potentiated by cycloheximide. Similar results were obtained with 0.5 μg/mL actinomycin D, an inhibitor of mRNA synthesis (not shown). Thus, the anti-CD3–induced increase in Fas expression was slightly potentiated by mRNA or protein synthesis inhibitors, whereas the cytokine-induced Fas expression increase was completely inhibited.

Effect of cycloheximide on the increase in Fas expression induced by anti-CD3 antibody or IFN-γ + IL-7. Fas expression was analyzed in human thymocytes after 24 hours of culture in control conditions or with anti-CD3 antibody or IFN-γ + IL-7 in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL cycloheximide. (A) A representative analysis is presented. Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine; only the last two steps were used for staining controls. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. (B) The anti-CD3–induced increase in the Fashi cell proportion was not significantly modified by cycloheximide. (C) The cytokine-induced increase was fully inhibited by cycloheximide. Data are the means ± SEM of 5 experiments. (□) Medium; (⊟) IL-7 + IFN-γ.

Effect of cycloheximide on the increase in Fas expression induced by anti-CD3 antibody or IFN-γ + IL-7. Fas expression was analyzed in human thymocytes after 24 hours of culture in control conditions or with anti-CD3 antibody or IFN-γ + IL-7 in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL cycloheximide. (A) A representative analysis is presented. Thymocytes were first labeled with anti-Fas antibody, then with biotin-coupled antimouse antibody, and lastly with Quantum Red-conjugated streptavidine; only the last two steps were used for staining controls. Fas staining is shown as solid profiles and staining controls as open profiles. (B) The anti-CD3–induced increase in the Fashi cell proportion was not significantly modified by cycloheximide. (C) The cytokine-induced increase was fully inhibited by cycloheximide. Data are the means ± SEM of 5 experiments. (□) Medium; (⊟) IL-7 + IFN-γ.

Sensitivity to cell death induced by an agonistic anti-Fas antibody.

One of the plasma membrane alterations occurring in the early stages of apoptosis is the externalization of phosphatidylserine at the cell surface; it triggers specific recognition and removal by phagocytes.27 Annexin-V is a calcium-dependent phospholipid binding protein with high affinity for phosphatidylserine and is used for the detection of apoptotic cells.28 After 18 hours of incubation with 2 μg/mL anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11), cells were examined for FITC-conjugated annexin-V. Because Fas-induced apoptosis is enhanced by metabolic inhibitors,6 7 10 μg/mL cycloheximide was added to thymocytes when indicated. Freshly isolated thymocytes were not sensitive to anti-Fas–induced apoptosis, even in the presence of cycloheximide (not shown).

Thus, we observed the sensitivity to Fas-induced apoptosis of human thymocytes after 24 hours of antigenic stimulation or cytokine activation (Fig 7). We also measured apoptosis in thymocytes previously cultured for 24 hours in control conditions, ie, with IgG1 antibody or medium alone. The results obtained with medium alone were always similar to those obtained with the IgG1 control. The analysis was performed in viable cells using forward- and side-scatter parameters, as previously described in the Materials and Methods; in this gate, the proportion of cells that incorporated propidium iodide was always less than 1%, and we thus report annexin-V-FITC binding only (Fig 7A). In the absence of cycloheximide, less than 10% of cells were sensitive to Fas apoptosis, whatever the stimulus. In the presence of 10 μg/mL cycloheximide, cells cultured with IgG1 or anti-CD3 antibody were weakly susceptible to Fas-induced apoptosis (6.2% ± 1.4% and 8.0% ± 2.5%, respectively, n = 5; Fig 7B). By contrast, 22.5% ± 2.3% of thymocytes cultured for 24 hours with IL-7 + IFN-γ underwent Fas-induced apoptosis (n = 5).

Anti-Fas–induced apoptosis in preactivated thymocytes. (A) Representative analysis of the apoptotic effect of an agonistic anti-Fas antibody on human preactivated thymocytes. After 24 hours of culture with IgG1 antibody, anti-CD3 antibody, or IFN-γ + IL-7, human thymocytes were collected and 105 cells were incubated with agonistic anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11, 2 μg/mL) or IgM antibody (2 μg/mL), with or without 10 μg/mL cycloheximide. Cells were harvested 18 hours later, washed with PBS, and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin-V to quantify apoptosis. Specific anti-Fas–mediated apoptosis was calculated by subtracting the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of control IgM from the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11. In the absence of cycloheximide, less than 10% of thymocytes underwent Fas-specific apoptosis. In the presence of cycloheximide, thymocytes activated by IFN-γ + IL-7 were more susceptible than anti-CD3–activated thymocytes to Fas-specific apoptosis. (B) Data are the means ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. (□) IgG1; (▧) anti-CD3; (▪) IL-7 + IFN-γ.

Anti-Fas–induced apoptosis in preactivated thymocytes. (A) Representative analysis of the apoptotic effect of an agonistic anti-Fas antibody on human preactivated thymocytes. After 24 hours of culture with IgG1 antibody, anti-CD3 antibody, or IFN-γ + IL-7, human thymocytes were collected and 105 cells were incubated with agonistic anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11, 2 μg/mL) or IgM antibody (2 μg/mL), with or without 10 μg/mL cycloheximide. Cells were harvested 18 hours later, washed with PBS, and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin-V to quantify apoptosis. Specific anti-Fas–mediated apoptosis was calculated by subtracting the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of control IgM from the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11. In the absence of cycloheximide, less than 10% of thymocytes underwent Fas-specific apoptosis. In the presence of cycloheximide, thymocytes activated by IFN-γ + IL-7 were more susceptible than anti-CD3–activated thymocytes to Fas-specific apoptosis. (B) Data are the means ± SEM of 5 independent experiments. (□) IgG1; (▧) anti-CD3; (▪) IL-7 + IFN-γ.

Fas-induced apoptosis in thymic subsets.

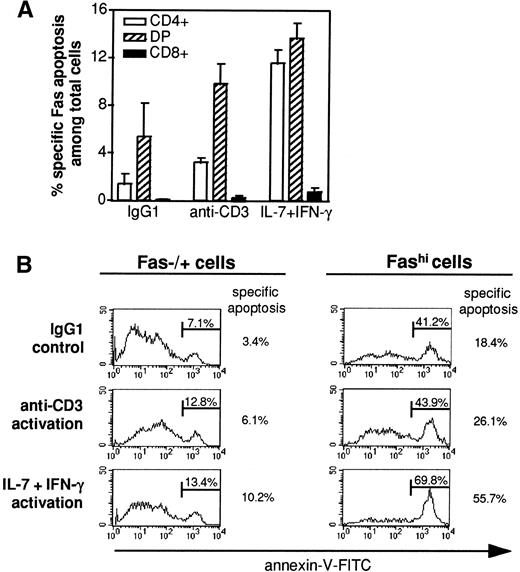

Three-color labeling with anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies and annexin-V was performed on thymocytes cultured with IgM or anti-Fas (clone CH-11) in the presence of cycloheximide. The proportion of annexin-positive cells was analyzed among CD4+, CD4+CD8+ (including CD8+CD4lo), and CD8+ cells, and the proportion of CD4+, CD4+CD8+, and CD8+ cells undergoing Fas-specific apoptosis among the total thymocyte population was calculated (Fig 8A). Whatever the conditions, CD8+ cells undergoing Fas-specific apoptosis represented less than 1% of total cells. In IgG1 and anti-CD3 conditions, CD4+CD8+ cells undergoing Fas-specific apoptosis composed the major subset of apoptotic thymocytes. When cells were preactivated by cytokines, the proportion of apoptotic CD4+ and CD4+CD8+ thymocytes were similar; apoptotic CD4+ cells were about three times more numerous among cytokine-activated cells than among anti-CD3–activated cells (11.6% ± 1.1% and 3.2% ± 0.4% of total cells, respectively, n = 3).

Fas-specific apoptosis in thymic subsets. (A) After 18 hours of incubation with agonistic anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11, 2 μg/mL) or IgM antibody (2 μg/mL) in the presence of 10 μg/mL cycloheximide, double-staining of CD4/CD8 subsets was performed in thymocytes before labeling with annexin-V. The proportion of (□) CD4+, (▧) CD4+CD8+ (DP), and (▪) CD8+cells that underwent Fas-specific apoptosis was calculated. Data are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The proportion of apoptotic CD4+ cells was three times higher in cytokine-activated thymocytes than in anti-CD3–activated thymocytes. (B) Fas staining was performed before annexin-V labeling, and the proportion of cells undergoing Fas-specific apoptosis was examined in Fas+/− and Fashi cells. A representative experiment is shown. Annexin-V stainings in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11 are presented and specific anti-Fas–mediated apoptosis was calculated by subtracting the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of control IgM from the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11. Fashi cells were always enriched in apoptotic cells, but cytokine-activated Fashi cells contained more apoptotic cells than did anti-CD3–activated cells.

Fas-specific apoptosis in thymic subsets. (A) After 18 hours of incubation with agonistic anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11, 2 μg/mL) or IgM antibody (2 μg/mL) in the presence of 10 μg/mL cycloheximide, double-staining of CD4/CD8 subsets was performed in thymocytes before labeling with annexin-V. The proportion of (□) CD4+, (▧) CD4+CD8+ (DP), and (▪) CD8+cells that underwent Fas-specific apoptosis was calculated. Data are the means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. The proportion of apoptotic CD4+ cells was three times higher in cytokine-activated thymocytes than in anti-CD3–activated thymocytes. (B) Fas staining was performed before annexin-V labeling, and the proportion of cells undergoing Fas-specific apoptosis was examined in Fas+/− and Fashi cells. A representative experiment is shown. Annexin-V stainings in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11 are presented and specific anti-Fas–mediated apoptosis was calculated by subtracting the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of control IgM from the proportion of annexin-positive cells in the presence of anti-Fas CH-11. Fashi cells were always enriched in apoptotic cells, but cytokine-activated Fashi cells contained more apoptotic cells than did anti-CD3–activated cells.

To examine if the level of Fas expression determines the sensitivity to Fas-induced apoptosis, we studied Fas-specific apoptosis in the presence of cycloheximide among Fas+/− and Fashi thymocytes (Fig 8B). Whatever the pretreatment, Fashi cells contained more annexin-V–positive cells compared with Fas−/+ cells. However, Fashi cells were twice as susceptible to Fas-specific apoptosis after cytokine-activated thymocytes as after anti-CD3 activation.

DISCUSSION

Fas antigen expression by human thymocytes can thus be upregulated by two signaling pathways, one antigen-dependent and the other cytokine-dependent. We showed that these two activation pathways differ (1) in the thymic subsets affected by the increase in the proportion of Fashi cells, (2) in their sensitivity to cyclosporin A and thus their dependence on calcineurin phosphatase activity, and (3) in their sensitivity to metabolic inhibitors and that (4) cytokine-activated and anti-CD3–activated cells differ in their susceptibility to Fas-induced apoptosis.

Intracellular regulatory mechanisms of Fas expression in human thymocytes.

Antigenic stimulation by an anti-CD3 antibody was effective in enhancing the proportion of Fashi thymocytes, as previously shown by Yonehara et al.17 This effect involved a small proportion of thymic cells, mainly in the CD4 lineage. We had previously shown that Fashi cells that accumulate in the thymus of MG patients, which are mainly CD4+ and CD4+CD8+, are enriched in cells autoreactive against the acetylcholine receptor.18 This finding is thus compatible with the antigen-dependent Fas upregulation in human thymocytes. In the same experiment, we compared CD25 and Fas expression regulation in the presence of various activation signals. We observed that the regulation of CD25 and Fas expression followed different kinetic profiles. Furthermore, PMA/ionomycin activation, which strongly increased CD25 expression in human thymocytes, slightly enhanced Fas expression, suggesting that Fas and CD25 are not regulated by the same intracellular pathways.

We used cyclosporin A, an inhibitor of calcineurin activation to identify intracellular signals underlying the activation-induced increase in Fas expression by human thymocytes. Activation of calcineurin, a calcium- and calmodulin-dependent phosphatase, is known to be an essential event in T-cell activation via the TCR.26 The increase in Fas expression induced by the TCR stimulation was partially inhibited by cyclosporin A, suggesting that calcineurin controlled this increase. This result is compatible with cyclosporin inhibition of Fas upregulation induced by TCR activation in murine T-cell hybridomas29 and by cross-linking of CD4 molecules in human peripheral lymphocytes.30 In contrast, the effect of IL-7 + IFN-γ was not affected by cyclosporin. Thus, antigen-dependent cyclosporin-sensitive and cytokine-dependent cyclosporin-insensitive intracellular pathways can both lead to Fas upregulation in human thymocytes.

The increase in Fas expression was differently sensitive to cycloheximide and actinomycin D when induced by antigenic or cytokine activation. Fas upregulation induced by the combination of IL-7 and IFN-γ requires de novo mRNA and protein synthesis. By contrast, Fas upregulation induced by antigenic activation was not inhibited by the metabolic inhibitors, suggesting that it uses preexisting thymocyte proteins.

Involvement of Fas in thymic apoptosis.

Thymocytes that are not positively selected may die from neglect31 and may compose the bulk of cells that die of apoptosis in the thymus.32 As previously described in mouse thymocytes,7 spontaneous apoptosis of human thymocytes was not modified by an antagonistic anti-Fas antibody (clone ZB4; not shown), suggesting that Fas-mediated apoptosis would not mediate death by neglect in the human thymus.

Fas-mediated apoptosis of freshly isolated mouse thymocytes was shown to require cycloheximide6 or actinomycin D.7 By contrast, even in the presence of cycloheximide, freshly isolated human thymocytes never underwent Fas-specific apoptosis in our experimental conditions. The presence of cycloheximide was required for Fas-induced apoptosis to occur in cytokine-activated thymocytes. Thymocyte resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis in the absence of metabolic inhibitors could be mediated by FAP-1 (Fas-associated phosphatase-1), which can inhibit Fas signaling33 and which is downregulated by actinomycin D.34 In human T cells, Fas-mediated apoptosis is mediated by intracellular glutathione, levels of which are reduced by cycloheximide35; this process could also contribute to thymocyte resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis.

We showed here that cytokine-activated thymocytes were more susceptible than anti-CD3–activated thymocytes to Fas-mediated apoptosis in vitro in the presence of cycloheximide. Soluble FasL has been described as inactive in mouse-activated splenic T cells36 or as inhibitory in human-activated peripheral T cells,37 whereas membrane FasL can induce apoptosis. Thus, resistance to apoptosis induced by the anti-Fas antibody (clone CH-11) in anti-CD3–activated cells could be due to inactivity of agonistic anti-Fas antibody (or soluble FasL) on these cells.

CD8+ cells that underwent Fas-specific apoptosis always formed a very minor subset. Apoptotic CD4+ cells were four times as numerous in cytokine-activated thymocytes as in anti-CD3–activated thymocytes, whereas the number of apoptotic CD4+CD8+ cells was similar in the two conditions. Thus, the difference in susceptibility to Fas apoptosis between cytokine-activated and anti-CD3–activated thymocytes is mainly due to CD4+ thymocytes.

Fashi cells were always enriched in annexin-positive cells relative to Fas+/− thymocytes. Freshly isolated FashiCD3int thymocytes were similarly shown to contain a large fraction of dead cells.16 However, Fas-specific apoptosis was more efficient in cytokine-activated Fashi cells than in anti-CD3–activated Fashicells. Cytokine activation might thus provide an additional signal to induce apoptosis in human thymocytes.

By contrast, Fisher et al7 showed that antigenic stimulation and Fas signal must occur simultaneously to induce Fas apoptosis in mouse thymocytes, a synergistic effect not mediated by Fas upregulation. This difference could be related to the high basal level of Fas antigen expression in mouse thymocytes, with about 80% of adult mouse thymocytes expressing Fas.38 Fas expression and susceptibility to Fas-specific apoptosis are thus clearly different in human and mouse thymocytes.

Fas was suggested to be involved in the negative selection in the human thymus.16,17 Fashi thymocytes are enriched in CD4+ cells in the human thymus.16-18 TCR stimulation increases Fas expression, mainly in cells of the CD4 lineage (CD4+ and CD4+CD8+thymocytes); moreover, Fashi thymocytes express an intermediate level of CD3 antigen16,18 and antigenic activation downregulates CD3 expression.25 Thus, in vivo Fashi thymocytes could have been previously activated by an antigenic stimulation. IL-7/IFN-γ activation seems to provide additional signal rendering thymocytes (particularly CD4+thymocytes) susceptible to Fas-induced apoptosis. In addition, Kishimoto and Sprent15 recently described a semimature subset (CD4+CD8-HSAhi) in the mouse thymus that is susceptible to negative selection in a Fas-dependent way. Taken together, these results suggest that a thymocyte subset in the CD4 lineage could be the target of Fas-mediated negative selection in the thymus. Cells able to produce FasL are poorly characterized in the human thymus, but both epithelial and dendritic cells were shown to express FasL in situ in the mouse thymus.39 Thus, thymic stromal cells could mediate apoptosis of a thymocyte subset through Fas/FasL interaction.

In conclusion, two different signaling pathways can increase Fas expression by human thymocytes in vitro. Antigenic stimulation upregulates Fas antigen expression in vitro, and this effect mainly involves the CD4 lineage. The cytokine pathway upregulates Fas in all thymic subsets and induces susceptibility to Fas-mediated apoptosis, whereas anti-CD3 activation is less efficient in this respect. These findings indicate that Fas has the potential to participate to the apoptosis of a human thymic subset in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Drs F. Lacour-Gayet and A. Serraf for providing thymuses. We are grateful to Dr J. Curnow for critical reading of the manuscript.

Supported by grants from Association Française contre les Myopathies (AFM), Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), and Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie des Travailleurs Salariés (CNAMTS). N.M. received a postdoctoral grant from the Singer-Polignac Foundation.

Address reprints requests to Nathalie Moulian, PhD, Laboratoire d’Immunologie Cellulaire et Moléculaire, CNRS UPRESA, Hôpital Marie-Lannelongue, 133, avenue de la Résistance, 92350 Le Plessis Robinson, France.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" is accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.