Alterations in the cellular redox potential by homocysteine promote endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction, an early event in the progression of atherothrombotic disease. In this study, we demonstrate that homocysteine causes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and growth arrest in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). To determine if these effects reflect specific changes in gene expression, cDNA microarrays were screened using radiolabeled cDNA probes generated from mRNA derived from HUVEC, cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine. Good correlation was observed between expression profiles determined by this method and by Northern blotting. Consistent with its adverse effects on the ER, homocysteine alters the expression of genes sensitive to ER stress (ie, GADD45, GADD153, ATF-4, YY1). Several other genes observed to be differentially expressed by homocysteine are known to mediate cell growth and differentiation (ie, GADD45, GADD153, Id-1, cyclin D1, FRA-2), a finding that supports the observation that homocysteine causes a dose-dependent decrease in DNA synthesis in HUVEC. Additional gene profiles also show that homocysteine decreases cellular antioxidant potential (glutathione peroxidase, NKEF-B PAG, superoxide dismutase, clusterin), which could potentially enhance the cytotoxic effects of agents or conditions known to cause oxidative damage. These results successfully demonstrate the use of cDNA microarrays in identifying homocysteine-respondent genes and indicate that homocysteine-induced ER stress and growth arrest reflect specific changes in gene expression in human vascular EC.

HYPERHOMOCYST(E)INEMIA (HH) is a significant independent risk factor for premature atherothrombotic disease.1-5 Up to 40% of patients diagnosed with coronary, cerebrovascular, or peripheral atherosclerosis have HH.3-6Although the majority of cases of HH are thought to be caused by an interplay between dietary and genetic factors, the genetic disorders are associated with the highest plasma levels of homocysteine, with cystathionine β-synthase deficiency (CBS)4-6 and 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency7 8being the most common. Regardless of the underlying cause of HH, the relationship between elevated blood homocysteine levels and premature vascular and thrombotic disease persists.

Earlier studies suggest that atherothrombosis associated with HH reflects endothelial cell (EC) injury and/or dysfunction. Homocysteine causes EC injury when administered to baboons9,10 or rats,11 or when added directly to cultured EC.12-15 Furthermore, deGroot et al14 showed that primary cultures of EC obtained from obligate heterozygotes for CBS deficiency are more sensitive to homocysteine-induced damage than control cells. In addition to causing injury, homocysteine has been shown to increase the procoagulant activity of cultured EC by (1) inducing a protease that activates factor V,16 (2) inhibiting protein C activation,17 (3) causing aberrant processing of thrombomodulin (TM),18 (4) inducing tissue factor activity,19 and (5) inhibiting the cellular binding sites for tissue plasminogen activator.20 Homocysteine also reduces nitric oxide production in vitro,21 a finding that could explain why diet-induced HH in monkeys22 and pigs23 causes impaired vasomotor regulatory function.

Currently, the mechanism by which elevated levels of homocysteine cause EC injury and/or dysfunction is relatively unknown. We, and others, have demonstrated in cultured human vascular EC that homocysteine increases the expression and synthesis of GRP78, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident chaperon and member of the 70-Kd heat-shock protein (HSP) family.24-26 In support of these in vitro findings, steady-state mRNA levels of GRP78 were also shown to be elevated in the livers of CBS-deficient mice that had HH.26Given that GRP78 is induced by agents or conditions known to elicit ER stress27 and that homocysteine impairs protein processing and secretion via the ER,18,28 these studies suggest that homocysteine alters the cellular redox state, thereby causing ER stress and leading to growth arrest.29 Whether these effects of homocysteine reflect specific changes in gene expression is not completely known.

To explore this possibility, cDNA microarrays were screened using radiolabeled cDNA probes generated from mRNA transcripts from human vascular EC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine. Herein, we provide a first step in identifying the gene pathways by which homocysteine alters EC function and show that homocysteine-induced ER stress and growth arrest reflect changes in gene expression specific for these effects. Furthermore, additional gene pathways demonstrate that homocysteine decreases the expression of a wide range of antioxidant enzymes that could enhance the adverse effects of agents and/or conditions known to cause oxidative damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and treatment conditions.

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated by collagenase treatment of human umbilical veins30 and cultured in EC medium (M199 medium containing 20% fetal bovine serum, 20 μg/mL EC growth factor, 90 μg/mL porcine intestinal heparin, 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells from passages 2 to 4 were used in these studies. The transformed HUVEC line, ECV304, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, MD) and cultured in EC medium. DL-Homocysteine or dithiothreitol (DTT) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was prepared in EC medium, sterilized by filtration, and added to the cell cultures.

[3H]thymidine incorporation.

HUVEC were grown to 70% confluency in EC medium in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of homocysteine or DTT (0.2 to 5.0 mmol/L) for 18 hours. During the last 4 hours of treatment, cells were labeled with [methyl-3H]thymidine (NEN Life Sciences, Guelph, Canada) at 1 μCi/mL. After labeling, cells were washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed in ice-cold 10% acetic acid, and washed with 95% ethanol. Incorporated [3H]thymidine was extracted in 0.2N NaOH and measured in a scintillation counter. Values were expressed as the mean ± SD from 3 separate experiments.

Metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitation.

HUVEC grown to 70% confluence in EC medium were cultured in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of homocysteine (0.2 to 5.0 mmol/L) for 8 or 18 hours. Cells were then metabolically labeled with 300 μCi/flask of EXPRE35S35S labeling mix (NEN) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) without methionine or cysteine for 1 hour. Cell lysates were prepared in 1 mL of lysis buffer (1% Triton-X100 in 25 mmol/L Tris, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 0.02% bovine serum albumin, 10 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0) that contained protease inhibitors, centrifuged to precipitate insoluble material, and incubated with protein A-Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Mississauga, Canada) to remove any material that binds nonspecifically to protein A. Samples were then incubated with either goat anti–von Willebrand factor (anti-vWF) antibodies (Affinity Biologicals, Hamilton, Canada) or control goat IgG in the presence of protein A-Sepharose overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the beads were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electropheresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, 1% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% bromophenol blue) and proteins separated on 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels under reducing conditions. Radiolabeled proteins were detected by fluorography after incubation with Amplify (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

vWF multimer analysis.

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by denaturation of HUVEC in lysis buffer that contained 1 mg/μL urea and 0.1% SDS. vWF multimers were separated on 1.2% agarose gels in 1X electrophoresis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, 0.384 mol/L glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH 8.3) run at 35 V overnight or until the buffer front was within 1 to 2 cm from the anodal end of the gel. For detection of vWF, proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, immunoblotted with anti-vWF antibodies, and visualized using the Renaissance chemiluminescence reagent (NEN).

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis.

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis was performed as described previously.26 Briefly, after fixation and permeabilization, HUVEC were immunostained with either anti-GRP78 (StressGen, Vancouver, Canada) or anti-vWF antibodies and images captured using Northern Exposure image analysis/archival software (Mississauga, Canada).

Preparation of total RNA.

Total RNA was isolated from cells using the RNeasy total RNA kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) and resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. Quantification and purity of the RNA was assessed by A260/A280 absorption, and RNA samples with ratios greater than 1.6 were stored at −70°C for further analysis.

Analysis of differential gene expression using a human cDNA microarray.

Poly (A)+ RNA was isolated from total RNA using Oligotex resin (Qiagen), as described previously.26 To generate radiolabeled cDNA probes, poly (A)+ RNA was reverse-transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) in the presence of [α-32P]dATP (NEN). The radiolabeled cDNA probes were purified from unincorporated nucleotides by gel filtration in Chroma Spin-200 columns (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and hybridized overnight at 68°C to a human cDNA microarray consisting of 588 known human genes under tight transcriptional control, as described by the manufacturer (Clontech). After a series of high-stringency washes (three 20-minute washes in 2X saline-sodium citrate [SSC], 1% SDS followed by two 20-minute washes in 0.1X SSC, 0.5% SDS) at 68°C, the membranes were exposed to x-ray film (Reflections NEF-496, NEN) and subjected to autoradiography. Changes in gene expression were quantified by densitometric scanning of the membranes using the ImageMaster VDS and Analysis Software (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Northern blot analysis.

Total RNA (10 μg/lane) was fractionated on 2.2 mol/L formaldehyde/1.2% agarose gels and transferred overnight onto Zeta-Probe GT nylon membranes (Bio-Rad, Toronto, Canada) in 10X SSC. The RNA was cross-linked to the membrane using a UV crosslinker (PDI Bioscience, Toronto, Canada) before hybridization. Specific probes were generated by labeling the cDNA fragments with [α-32P]dCTP (NEN) using a random primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Laval, Canada). After overnight hybridization at 43°C, the membranes were washed as described by the manufacturer, exposed to x-ray film, and subjected to autoradiography. Changes in steady-state mRNA levels were quantified by densitometric scanning of the blots as described earlier. To correct for differences in gel loading, integrated optical densities were normalized to human glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). cDNA probes encoding Id-1 (GenBank/EBI accession no. AA582212), natural killer cell–enhancing factor B (NKEF-B) (no. AA100194), proliferation-associated protein (PAG) (no. AA204896), sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP) (no. AA568572), clusterin (no. AA614020), growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible (GADD) genes, GADD153 (no. AA627477) and GADD45 (no. AA147214) were obtained from Genome Systems (St Louis, MO). The cDNA probe encoding GRP78 has been described previously.26

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical differences between the homocysteine-treated and control groups were determined by analysis of variance. If a significant difference between treated and control groups was demonstrated, an unpaired Student’s t-test was performed for each point. For all analyses, P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of homocysteine on HUVEC viability and growth.

To examine the effect of homocysteine on cell viability,51Cr release assays were performed as described previously.14 Exposure of HUVEC to 5 mmol/L homocysteine for up to 18 hours had no significant effect on overall cell viability, compared with control cells (19.3% ± 0.5% v 17.4% ± 0.6% release, respectively, at 6 hours, n = 3; 27.9% ± 2.3%v 28.1% ± 0.7% release, respectively, at 18 hours, n = 3). The time-dependent basal release of 51Cr from HUVEC is consistent with previous studies.14 In contrast to 5 mmol/L homocysteine alone, 5 mmol/L homocysteine in the presence of 4 μmol/L Cu2+, which is known to generate H2O2 and induce EC lysis,12-15caused a significant increase (P > .01) in the release of51Cr at 18 hours (28.1% ± 0.7% v 81.4% ± 1.2% release, respectively, n = 3).

To determine the effect of homocysteine on cell proliferation, HUVEC were cultured in the absence or presence of various concentrations of homocysteine and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured. As shown in Fig 1, HUVEC exposed to homocysteine for 18 hours demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in DNA synthesis and is consistent with earlier studies.29 In addition to homocysteine, the thiol-containing reducing agent DTT also caused a similar dose-dependent decrease in DNA synthesis (data not shown).

Effect of homocysteine on DNA synthesis. Primary HUVEC were incubated in EC medium in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of homocysteine for 18 hours. [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured during the last 4 hours. Values represent the mean ± SD from 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. * P < .05 v untreated HUVEC, **P< .01.

Effect of homocysteine on DNA synthesis. Primary HUVEC were incubated in EC medium in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of homocysteine for 18 hours. [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured during the last 4 hours. Values represent the mean ± SD from 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. * P < .05 v untreated HUVEC, **P< .01.

Homocysteine induces ER stress in HUVEC.

Previous studies have shown that intracellular transport of vWF and TM via the ER is selectively inhibited by homocysteine in HUVEC.18,28 Homocysteine also increases the expression and synthesis of GRP78, a resident ER chaperon induced by agents or conditions known to adversely affect ER function.24-26 To further investigate the effect of homocysteine on ER function, vWF processing and secretion, and its interaction with GRP78 were examined in HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine.

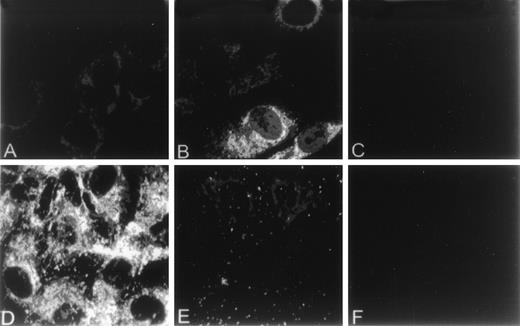

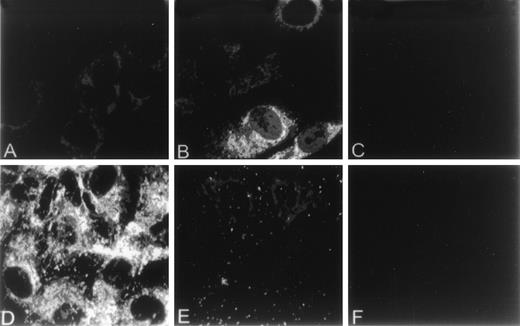

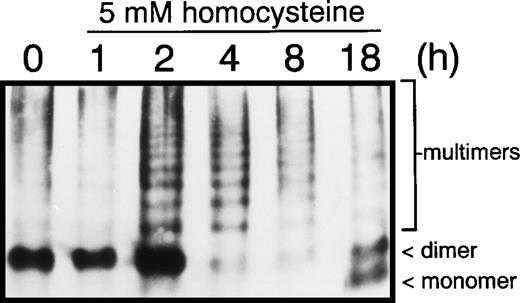

The effect of homocysteine on intracellular levels and distribution of GRP78 and vWF in HUVEC was examined by indirect immunofluorescence using anti-vWF or anti-GRP78 antibodies. In control HUVEC, GRP78 was concentrated in the perinuclear region, consistent with its presence in the ER (Fig 2A). In contrast, both the distribution and intensity of GRP78 immunostaining was markedly enhanced in HUVEC exposed to homocysteine (Fig 2B). Unlike GRP78, vWF immunostaining and localization were dramatically reduced in HUVEC exposed to homocysteine (Fig 2E), compared with control cells (Fig 2D). As controls, no specific staining was observed in untreated HUVEC incubated with either normal mouse (Fig 2C) or rabbit IgG (Fig 2F). Consistent with these findings, intracellular levels of vWF dimers were dramatically decreased after 4 hours in HUVEC exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine (Fig 3).

Effect of homocysteine on the cellular localization of GRP78 and vWF. HUVEC plated on gelatin-coated glass coverslips were cultured in the absence (A,D) or presence (B,E) of 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 18 hours. After treatment, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with antibodies against either GRP78 (A,B) or vWF (D,E). Antibodies were subsequently detected using fluorescein-labeled secondary antibodies. Parallel experiments using normal mouse (C) or rabbit IgG (D) were performed to assess nonspecific immunofluorescence.

Effect of homocysteine on the cellular localization of GRP78 and vWF. HUVEC plated on gelatin-coated glass coverslips were cultured in the absence (A,D) or presence (B,E) of 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 18 hours. After treatment, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with antibodies against either GRP78 (A,B) or vWF (D,E). Antibodies were subsequently detected using fluorescein-labeled secondary antibodies. Parallel experiments using normal mouse (C) or rabbit IgG (D) were performed to assess nonspecific immunofluorescence.

Effect of homocysteine on vWF multimerization. HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 1, 2, 4, 8, or 18 hours were denatured in lysis buffer, the lysates fractionated on 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. vWF monomers, dimers, and multimers were detected by immunoblotting using anti-vWF antibodies.

Effect of homocysteine on vWF multimerization. HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 1, 2, 4, 8, or 18 hours were denatured in lysis buffer, the lysates fractionated on 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. vWF monomers, dimers, and multimers were detected by immunoblotting using anti-vWF antibodies.

Stable association of GRP78 with misfolded, improperly glycosylated, or incompletely assembled proteins in the ER leads to retention and intracellular degradation.31-33 To determine whether GRP78 was capable of stably binding to misfolded vWF within the ER, HUVEC exposed to various concentrations of homocysteine for 8 or 18 hours were metabolically labeled with [35S]cysteine and [35S]methionine, and vWF from cell lysates was immunoprecipitated with anti-vWF antibodies as described in the Methods. Bands that corresponded to mature and pro-vWF were detected in immunoprecipitated eluates from HUVEC treated without or with homocysteine (Fig 4). However, coimmunoprecipitation of vWF with GRP78 was observed only in HUVEC treated with 1 or 5 mmol/L homocysteine for 8 hours or 5 mmol/L homocysteine for 18 hours. Taken together, these findings imply that GRP78 binds to misfolded vWF, prevents its secretion from the ER and likely directs aberrantly folded vWF to the degradative machinery.

Homocysteine increases the stable association between GRP78 and vWF. HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 0.2, 1.0, or 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 8 or 18 hours were metabolically labeled for 1 hour in the presence of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. Radiolabeled proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-vWF antibodies, separated on 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions, and detected by fluorography. Immunoprecipitation of pro and mature vWF coprecipitated GRP78. kD, molecular mass markers.

Homocysteine increases the stable association between GRP78 and vWF. HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 0.2, 1.0, or 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 8 or 18 hours were metabolically labeled for 1 hour in the presence of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. Radiolabeled proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-vWF antibodies, separated on 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions, and detected by fluorography. Immunoprecipitation of pro and mature vWF coprecipitated GRP78. kD, molecular mass markers.

Effect of homocysteine on differential gene expression in HUVEC.

Previous studies have shown that cDNA arrays provide a rapid and effective method in monitoring differential gene expression.34-38 To investigate the possibility that homocysteine-induced ER stress and growth arrest reflect specific changes in gene expression in ECs, a human cDNA microarray that contained 588 known human genes was screened using radiolabeled cDNA generated from total poly (A)+ RNA from primary HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 5 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 or 18 hours. After hybridization, the cDNA array membranes were washed under high stringency and the hybridization patterns analyzed by autoradiography. The level of nonspecific hybridization was low since the negative DNA controls, including M13mp18(+) strand DNA, λDNA, and pUC18, failed to show any hybridization signal. To ensure accurate comparisons in the expression levels of each gene on the cDNA array, hybridization signals were normalized to the signals obtained from housekeeping gene controls (ie, ubiquitin, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, α-tubulin, human leukocyte antigen [HLA] class 1 histocompatibility antigen C-4, β-actin, 23-Kd highly basic protein, ribosomal protein S9) on the same array.

As shown in Fig 5, the hybridization patterns between wild-type and homocysteine-treated HUVEC were similar. However, analysis of the cDNA microarray showed that a total of 16 of 588 (2.7%) of the known human genes were differentially expressed in primary HUVEC exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine for 4 or 18 hours (Table1). Similar changes in gene expression were also observed in the ECV304 cell line cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine (data not shown). The percentage change in gene expression observed in this study is consistent with the recent observation that 2.5% of genes are regulated in HepG2 hepatoma cells exposed to β-mercaptoethanol, another thiol-containing agent known to cause ER stress and growth arrest.39 Of these genes, 9 were shown to be induced by homocysteine, while 7 were downregulated. Among the genes detected with significantly higher expression (>10-fold) was GADD153, a stress-response gene known to be induced by agents or conditions that adversely affect ER function.40 ATF-4, a stress-inducible transcription factor, was also shown to be induced by homocysteine and is consistent with earlier studies using mRNA differential display to identify ATF-4 as a homocysteine-inducible gene.24 Other inducible genes included Id-1, guanine nucleotide-binding protein G-S, SREBP, transcriptional repressor protein YY1, and the transcription factor ETR103. Genes shown to be downregulated by homocysteine included the antioxidant enzymes NKEF-B, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, clusterin, and PAG, as well as FRA-2, adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent DNA helicase, and cyclin D1. The observation that the majority of significant changes in gene expression occurred at 4 hours and declined by 18 hours suggests that homocysteine causes an initial early response in EC gene expression, followed by an adaptive response that likely involves cellular factors that influence the metabolism or elimination of intracellular homocysteine.

cDNA microarray analysis of changes in gene expression in primary HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine. [32P]-labeled cDNA probes generated from poly (A)+ RNA from control HUVEC (A) or HUVEC exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine for either 4 (B) or 18 hours (C) were hybridized to a cDNA microarray containing 588 known human genes. After a series of high-stringency washes, hybridization patterns were analyzed by autoradiography. Upward or downward arrows indicate the location within the array of genes increased or decreased, respectively, by homocysteine at 4 or 18 hours, v untreated cells. The relative expression levels of specific cDNAs was assessed by comparison with a wide range of housekeeping genes. Results are representative of 2 separate hybridization experiments.

cDNA microarray analysis of changes in gene expression in primary HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine. [32P]-labeled cDNA probes generated from poly (A)+ RNA from control HUVEC (A) or HUVEC exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine for either 4 (B) or 18 hours (C) were hybridized to a cDNA microarray containing 588 known human genes. After a series of high-stringency washes, hybridization patterns were analyzed by autoradiography. Upward or downward arrows indicate the location within the array of genes increased or decreased, respectively, by homocysteine at 4 or 18 hours, v untreated cells. The relative expression levels of specific cDNAs was assessed by comparison with a wide range of housekeeping genes. Results are representative of 2 separate hybridization experiments.

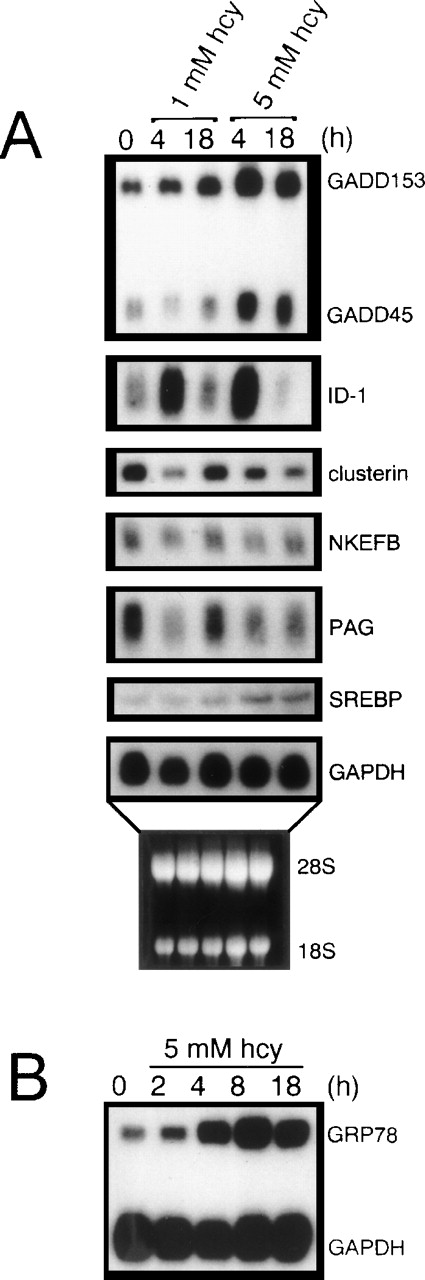

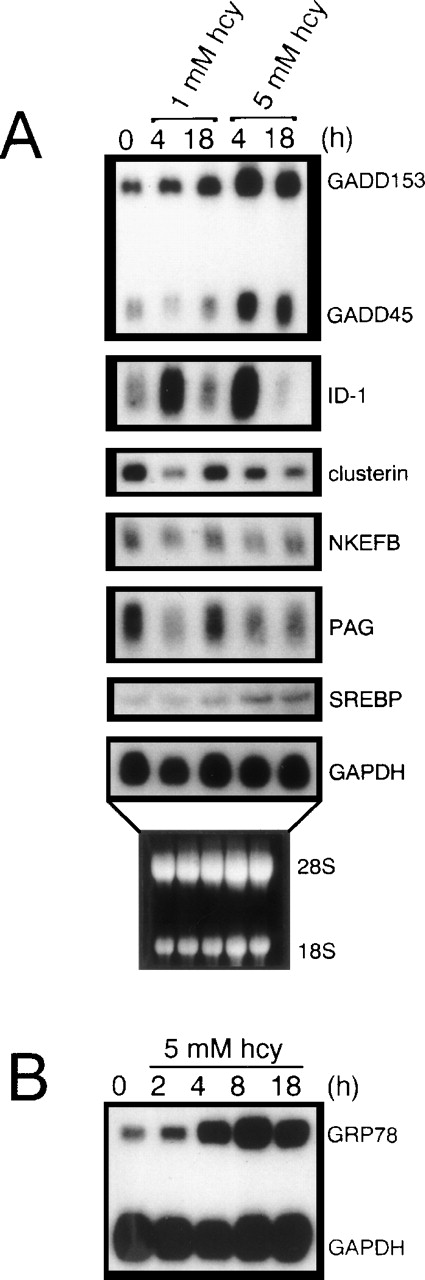

To test the reliability of the cDNA microarrays in identifying differentially expressed genes, we analyzed 7 different homocysteine-responsive genes by Northern blot analysis (Fig6A). In each case, the relative expression levels of these homocysteine-responsive genes observed on Northern blots was consistent with the differential gene expression identified by microarray hybridization (Table 2). As a positive control, homocysteine was shown to induce the expression of GRP78 (Fig 6B), a finding consistent with our earlier studies.26

Northern blot analysis substantiating the consistency of the cDNA microarray results. Total RNA (10 μg/lane) isolated from HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine for the indicated time periods was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization, followed by autoradiography. (A) Effect of homocysteine on Id-1, NKEFB, clusterin, PAG, SREBP, GADD153, and GADD45 mRNA levels. (B) Effect of homocysteine on GRP78 mRNA levels. Hybridization to a human GAPDH probe was used to normalize RNA loading. The results are representative of 2 separate experiments using 2 different samples of RNA.

Northern blot analysis substantiating the consistency of the cDNA microarray results. Total RNA (10 μg/lane) isolated from HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine for the indicated time periods was analyzed by Northern blot hybridization, followed by autoradiography. (A) Effect of homocysteine on Id-1, NKEFB, clusterin, PAG, SREBP, GADD153, and GADD45 mRNA levels. (B) Effect of homocysteine on GRP78 mRNA levels. Hybridization to a human GAPDH probe was used to normalize RNA loading. The results are representative of 2 separate experiments using 2 different samples of RNA.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies using cultured human vascular EC have shown that alterations in the cellular redox potential by homocysteine impair protein processing and secretion via the ER18,28 and increase expression of the ER stress-response gene, GRP78.24-26 In this study, we demonstrate that homocysteine causes ER stress in cultured human vascular EC by (1) decreasing intracellular levels of vWF, (2) inducing the expression and synthesis of GRP78, and (3) increasing the stable association of vWF with GRP78. Furthermore, homocysteine was shown to cause a dose-dependent decrease in DNA synthesis, a result consistent with earlier findings.29 Taken together, these findings both support and extend previous studies using cultured vascular EC18,24-26 28 and suggest that homocysteine acts intracellularly by altering the cellular redox state, thereby leading to ER stress and growth arrest in EC.

To determine if homocysteine-induced ER stress and growth arrest results in specific changes in gene expression in EC, cDNA microarrays were screened. This approach was taken based on previous studies showing that cDNA microarrays provide a powerful approach for studying differential gene expression associated with the pathogenesis of cancer and other diseases.34-38 As a result of this analysis, we demonstrate that the effects of homocysteine on ER function and cell growth reflect specific changes in gene expression. Furthermore, additional gene profiles indicate that homocysteine suppresses the ability of EC to protect themselves from agents or conditions known to elicit oxidative damage.

Although relatively high concentrations of homocysteine (≥1 mmol/L) were used to evaluate changes in gene expression, there was no effect on overall cell viability, a finding consistent with previous studies that indicated EC from normal individuals are relatively resistant to high doses of homocysteine.12-19 This may reflect the fact that only a small percentage of exogenous homocysteine (<1%) added to the culture medium is actually taken up intracellularly.41 Indeed, we have shown that intracellular concentrations of homocysteine are increased only 2-fold and 5-fold in HUVEC exposed to 1 or 5 mmol/L homocysteine, respectively, compared with untreated cells.26 Thus, the high doses required to alter gene expression in vitro likely reflects the need to increase intracellular levels of homocysteine by overcoming the cellular factors that influence the metabolism and/or elimination of homocysteine.

The observation that homocysteine induces the expression of GADD45, GADD153, ATF-4, and YY1 provides genetic evidence that homocysteine causes ER stress. Although GADD45, a downstream effector of p53, and GADD153, a member of the C/EBP gene family of transcription factors,42 have also been shown to be induced by growth arrest, by DNA damage, or by UV irradiation,43-45 recent studies indicate that inducers of GRP78 increase the expression of these genes,46 and that the induction of GADD153 is more responsive to ER stress.40 Based on previous studies demonstrating that DTT, a thiol-containing agent known to cause ER stress, induces the expression of both GRP78 and GADD153,47our findings are not unexpected. Although the physiologic significance of GADD gene induction by homocysteine has not been defined, overexpression of the GADDs causes growth arrest in several cell types.48,49 Furthermore, the importance of GADD153 in cellular growth and differentiation comes from the molecular analysis of human sarcomas wherein the rearrangement of the GADD153 gene gives rise to a naturally occurring altered form of GADD153 incapable of eliciting growth arrest.50 Given our findings, as in other studies,29 that homocysteine inhibits EC growth, the GADDs may play a potential role in linking ER stress to alterations in cell growth and proliferation. This concept is also supported by our observation that DTT, a known inducer of ER stress,27 also decreases EC proliferation. The homocysteine-induced expression of ATF-4, a member of the activating transcription factor/cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-responsive element-binding protein (ATF/CREB) family of transcription factors, is consistent with previous studies.24 ATF-4 is induced by increased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations51 and by anoxia,52 conditions known to alter ER function. YY1, a member of the GLI zinc finger family, has been shown to specifically enhance the transcriptional activation of the GRP78 promoter under a variety of ER stress conditions.53 These include depletion of ER Ca2+ stores, inhibition of glycosylation and formation of misfolded proteins. Thus, the ability homocysteine to increase the expression of YY1 would not only enhance the expression of GRP78, but could potentially mediate stress signals generated from the ER to the nucleus. Given that YY1 affects cell growth54 and acts as a transcriptional repressor,55 the induction of YY1, like the GADD genes, by homocysteine may also play a role in mediating EC growth.

Alterations in the expression of genes known to mediate cell growth and differentiation is consistent with the finding that homocysteine causes a dose-dependent decrease in EC growth. Overexpression of Id-1, a member of the helix-loop-helix transcriptional regulators,56 suppresses cell differentiation in mammary epithelial cells57 and murine erythroleukemia cells.58 The ability of homocysteine to decrease cyclin D1, a positive growth regulator during the early G1phase,27 and FRA-2, a transcription factor known to promote osteoblast differentiation,59 also suggests that homocysteine affects the expression of growth response genes in ECs. Whether a decrease in cell growth plays a role in protecting EC from homocysteine-induced injury and/or dysfunction is currently unknown.

The ability of homocysteine to inhibit the expression of the antioxidant enzymes glutathione peroxidase and NKEF-B are consistent with our previous findings26 and suggest that homocysteine may promote EC dysfunction and/or injury by indirectly enhancing the cytotoxic effect of agents or conditions that cause oxidative stress. This concept is further supported by the recent observation that homocysteine impairs the ability of glutathione peroxidase to detoxify peroxides60 and acts synergistically with H2O2 to enhance mitochondrial damage.61 In addition to these antioxidant enzymes, homocysteine decreased the expression of clusterin and PAG. Clusterin, a multifunctional heterodimeric glycoprotein, has been implicated in a wide range of physiologic functions such as lipid transport, tissue repair and remodelling, membrane protection, and promotion of cell interactions.62 Recent studies have also demonstrated that induction of clusterin during the development of atherosclerosis may represent a protective response to the oxidative stress associated with the development of atherosclerosis.63,64 Furthermore, because clusterin is a novel potent inhibitor of complementation-mediated cytolysis, the ability of homocysteine to decrease clusterin gene expression could potentially enhance complement activation at the site of vessel wall damage, which results in increased EC injury and/or dysfunction. PAG, a novel antioxidative protein family member responsive to oxidative stress,65-67induces cell growth and differentiation by blocking c-Abltyrosine kinase activity. The ability of homocysteine to decrease PAG expression would not only enhance the cytotoxic effects of oxidants but could suppress EC growth and differentiation.

Although we have identified several gene pathways by which homocysteine could potentially influence EC function and growth, a number of relevant issues remain to be explored. Additional studies are needed to determine if these homocysteine-dependent changes in gene expression in cultured vascular EC are observed in vivo. The fact that GRP78 is induced in the livers of CBS-deficient mice,26 and that the activity of several antioxidant enzymes is altered in rabbits fed a high methionine diet68 supports our findings and suggests that our in vitro studies likely reflect the actions of homocysteine in vivo. Furthermore, it is not known if the ability of homocysteine to cause ER stress directly influences EC growth. Based on the observation that agents known to adversely affect ER function cause inhibition of protein synthesis69 and cell growth,70-72 it is likely that elevated levels of intracellular homocysteine act in a similar fashion. As a result of previous studies demonstrating that homocysteine induces smooth muscle cell proliferation and increases the expression of the cyclin genes,29 it will be of interest to determine if the changes in gene expression observed in smooth muscle cells by homocysteine inversely correlate with some of the genes identified in these studies.

In summary, we have shown that homocysteine-induced ER stress and growth arrest in vascular EC involves changes in gene expression specific for these effects. Furthermore, the ability of homocysteine to decrease the expression of several antioxidant enzymes suggests that homocysteine could indirectly enhance the effects of agents or conditions known to cause oxidative stress. We also show the utility of cDNA microarrays as an initial screening approach for the identification of homocysteine-respondent genes in EC. Based on the high yield of information obtained using an array of fewer than 600 known human genes, a more comprehensive survey of gene expression patterns, using a more complete array of human genes, will not only provide additional important information on the mechanism by which homocysteine promotes EC dysfunction but will also increase our understanding of the gene pathways involved in the pathogenesis of HH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr Catherine Hayward for technical assistance in analyzing the vWF multimers.

Supported by Research Grant No. NA-3307 from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario (to R.C.A.). P.A.O. was a recipient of a Douglas C. Russel Memorial Scholarship and an Ontario Graduate Scholarship. R.C.A. is a Research Scholar of the R.K. Fraser Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

Author notes

Address reprint requests to Richard C. Austin, PhD, Hamilton Civic Hospitals Research Centre, 711 Concession St, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, L8V 1C3; e-mail: raustin@thrombosis.hhscr.org.

![Fig. 1. Effect of homocysteine on DNA synthesis. Primary HUVEC were incubated in EC medium in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of homocysteine for 18 hours. [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured during the last 4 hours. Values represent the mean ± SD from 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. * P < .05 v untreated HUVEC, **P< .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.959.415k20_959_967/5/m_blod41520001x.jpeg?Expires=1767729032&Signature=zqDjs7fofKjOuiWzuHn8gKH6izHYzRhCqnqu2YEK1PDGubMOGWUmH41fA7y3UWQWD2OWD6P0UNzhSYaKGRPX6bDQ9b~qWlDQ0gaOLBC2aq5woeJJRJEkXJ3X~PkW-hESVnHB1yHg6s8Z7vTkeieRuwhlPa2VOk~C688G3LNVbwfEPPInwGTg3yZeWrdFMQXkw-0pQQm09psHR8cXqVnSeaUwdHB~LkaFtVXfnZICKZVX-OUOQYlr-IxgKQnb0x0KrUmK9AaU~Bn5VbU33aVWyL4r4htvQnWE9rtTElCs~CUcAxQdzTuW~ZrLj2jw-DC8zugpWQIvyEkE-Bt3sW9xfQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Homocysteine increases the stable association between GRP78 and vWF. HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 0.2, 1.0, or 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 8 or 18 hours were metabolically labeled for 1 hour in the presence of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. Radiolabeled proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-vWF antibodies, separated on 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions, and detected by fluorography. Immunoprecipitation of pro and mature vWF coprecipitated GRP78. kD, molecular mass markers.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.959.415k20_959_967/5/m_blod41520004w.jpeg?Expires=1767729032&Signature=Duvdskkhq2y3JfZi5mmqZxd0iFBzKYJBbiUkGPznZ0RbjDvqkMDq5Ux5o7hsWD-QuH6GcJvTTm0PiIBZlgDC~BM4ZErVwo5B8JnU-~AOqgHkrQxRu7pQlSbGfclSDqGt5mre32RlPQUUwtloltoV5UwKHX-ugXBaLvwRjro6W7QqZ-~QVLhJ0TaZCW9VvHC0kehDFTMustM3LUNLpCGkn8tMNTo1xt5zr2X2I34TSvaSIeSkZMtI8zD8xk2OtKW4~gJWpDPZHJtK-HrFg1uWS-frQ6k92FtK~vYl6PJqqNxS6mnSbdRttO5d8sCOygvP5SSaNh8isu2IrDTqU94Wbw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. cDNA microarray analysis of changes in gene expression in primary HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine. [32P]-labeled cDNA probes generated from poly (A)+ RNA from control HUVEC (A) or HUVEC exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine for either 4 (B) or 18 hours (C) were hybridized to a cDNA microarray containing 588 known human genes. After a series of high-stringency washes, hybridization patterns were analyzed by autoradiography. Upward or downward arrows indicate the location within the array of genes increased or decreased, respectively, by homocysteine at 4 or 18 hours, v untreated cells. The relative expression levels of specific cDNAs was assessed by comparison with a wide range of housekeeping genes. Results are representative of 2 separate hybridization experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.959.415k20_959_967/5/m_blod41520005w.jpeg?Expires=1767729032&Signature=CD0-QqPvqhieQfxeghnsLBaQFJqpoBB7~5GiR~BKO5od65GV3g2SzxOB2ntB~TD4Su8zjW5iy83FEqBXvepf-kccPLslRJ2706QSNlYWTl~mA9gthCn8bj9H3sMgAraehF2P5V9uO4XCcSzvAaDPxgNb9nRcthvbl-kiY4zvB46TCFYax3~f0QS7tuvZgheCacjyI8Xk4mLnwtKTblvbXBHdW89GSTcdrb6VgaFBQ4BF1cEixAF8G7CPU38EqVM~f0p~~0DkwHmDQQD-c7N-AoHojQKR9dcVywGXVcvY4~NjxykQ1Qfw96CXdGUju094QoS1kQ3yZDgxEbeYia6A4A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 1. Effect of homocysteine on DNA synthesis. Primary HUVEC were incubated in EC medium in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of homocysteine for 18 hours. [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured during the last 4 hours. Values represent the mean ± SD from 3 wells from 3 separate experiments. * P < .05 v untreated HUVEC, **P< .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.959.415k20_959_967/5/m_blod41520001x.jpeg?Expires=1767856548&Signature=vXRjmMvhVIWBlkqDY00k3u0idXqL87grNnk29anA45oxKT5lROY4cvUo4Xf0vBeefgp9G-jAbgxjSAJELvFSbWqcQVqXtoAIDkQgsoveNkea6NABDeVntB-YYSrCxsCshCkU4V-zSV6ZLj7Ilz2MgGa4g95I6mCTx0g7wcyYigaH5slx11TueBHBnzqQneW1Tz4abtMeY6U5rvn0v753yYeZ7OPo8VPOzrpn1qRdJFrzN6X1-49tuUC-9JtJ-sgo2H7SynR2b2YiRBsbbNKBka3c58bYeIFaGGVRqe02GGjXmReh2pu2Bvlpz1MvdakGghsCViYpg~ba3B2w8AtazQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 4. Homocysteine increases the stable association between GRP78 and vWF. HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of 0.2, 1.0, or 5.0 mmol/L homocysteine for 8 or 18 hours were metabolically labeled for 1 hour in the presence of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine. Radiolabeled proteins from cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-vWF antibodies, separated on 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel under reducing conditions, and detected by fluorography. Immunoprecipitation of pro and mature vWF coprecipitated GRP78. kD, molecular mass markers.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.959.415k20_959_967/5/m_blod41520004w.jpeg?Expires=1767856548&Signature=XlC7iTVNVFKAKG8wu~NsPBAQXO7-KSdrT-JuZT3Nwko7KH4GngvISSPxjQlUIkAQNPRkVdJjiZN6DbbOS76jGLuvCHQ1LnxOf7uUilYo8I~Pi1AJH3vjqoN~CpMmBJtr2UtdGVWEupdKaTa5nrj8fGpfoYkYgzV9tPW3Iw629fkNAoZIpLklHrZg9GoYABMODARFQAVhyzgUMcic2-peNcMSp5lxIkY91v98I1kw6mPDeAUCC746tng5sD4D4PkC1R~6p9OyedmFF3wQ2rppF6KqpzxeB1XZlGnv2JZ3ntjrSybytetSQBQSqS2fWkF3ndAdKj-bXS~HrKnXdWVrYQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Fig. 5. cDNA microarray analysis of changes in gene expression in primary HUVEC cultured in the absence or presence of homocysteine. [32P]-labeled cDNA probes generated from poly (A)+ RNA from control HUVEC (A) or HUVEC exposed to 5 mmol/L homocysteine for either 4 (B) or 18 hours (C) were hybridized to a cDNA microarray containing 588 known human genes. After a series of high-stringency washes, hybridization patterns were analyzed by autoradiography. Upward or downward arrows indicate the location within the array of genes increased or decreased, respectively, by homocysteine at 4 or 18 hours, v untreated cells. The relative expression levels of specific cDNAs was assessed by comparison with a wide range of housekeeping genes. Results are representative of 2 separate hybridization experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/94/3/10.1182_blood.v94.3.959.415k20_959_967/5/m_blod41520005w.jpeg?Expires=1767856548&Signature=IbEgoH0pB8YtfXOtmPO8RQ~OVrKri41HGM3~LZkGA5BlOraNFdCSykuu1En2DU4qLtlcvodKqf-xvqQZg7zstTih1sMI1WqjuhM7U-74Kw6-FgWVFJ1w56g2-P~pOM0VKlKeqmdz5FQ8QiLESZWVo57wnyRobxqHovLxA8ztiqzqXiQET-X0Q4cIyCp9M7rmM3kDPAT52JHiQg--Ael6OeogxvFlcV48mVzTO-a10X-lDUGCnHC3Wl~WYuq~QAMcD1vZ89IAe0z66llOgEoiVSdPBq74JJjNMuPHU8mEQIF6GgvlZhKGnxkgKqTVS~44hBn~BR5A6Dwt9p7livGpZA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)