The superoxide-forming nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced (NADPH) oxidase of human phagocytes comprises membrane-bound and cytosolic proteins, which, upon cell activation, assemble on the plasma membrane to form the active enzyme. Patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) are defective in one of the phagocyte oxidase (phox) components, p47-phox or p67-phox, which reside in the cytosol of resting phagocytes, or gp91-phox or p22-phox, which constitute the membrane-bound cytochrome b558. In four X-linked CGD patients we have identified novel missense mutations inCYBB, the gene encoding gp91-phox. These mutations were associated with normal amounts of nonfunctional cytochromeb558 in the patients' neutrophils. In phorbol-myristate–stimulated neutrophils and in a cell-free translocation assay with neutrophil membranes and cytosol, the association of p47-phox and p67-phox with the membrane fraction of the cells with Cys369→Arg, Gly408→Glu, and Glu568→ Lys substitutions was strongly disturbed. Only a Thr341→Lys substitution, residing in a region of gp91-phox involved in flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) binding, supported a normal translocation. Thus, the introduction or reversal of charge at residues 369, 408, and 568 in gp91-phox destroys the correct binding of p47-phox and p67-phox to cytochrome b558. Based on mutagenesis studies of structurally related flavin-dependent oxidoreductases, we propose that the Thr341→Lys substitution results in impaired hydride transfer from NADPH to FAD. Because we found no electron transfer in solubilized neutrophil plasma membranes from any of the four patients, we conclude that all four amino acid replacements are critical for electron transfer. Apparently, an intimate relation exists between domains of gp91-phox involved in electron transfer and in p47/p67-phox binding.

Phagocytic leukocytes use reactive oxygen metabolites to kill ingested microorganisms. The first step in the production of these compounds is the generation of superoxide by the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced (NADPH) oxidase enzyme in these cells. For an active NADPH oxidase, at least 5 different proteins are required: the membrane-bound cytochrome b558 (a flavocytochrome consisting of the subunits gp91-phox and p22-phox)1,2 and 3 cytosolic proteins, p47-phox,3 p67-phox,4 and a low-molecular-weight guanosine 5′-triphosphate–binding (GTP-binding) proteinrac.5,6 A fourth cytosolic oxidase component, namely, p40-phox,7,8 has been described. However, this latter protein is not essential for oxidase activity because complete reconstitution of oxidase activity in a cell-free assay is achieved by purified cytochrome b558 with recombinant p47-phox, p67-phox, and racprotein.9

In resting neutrophils, most of the cytochrome b558resides in the membrane of specific granules or secretory vesicles.10,11 Upon cell activation, these organelles fuse with the plasma membrane, which results in expression of cytochromeb558 in the plasma membrane. At the same time, a complex of cytosolic phox proteins translocates to the plasma membrane and forms an enzymatically active complex with cytochromeb558.12-14

Patients suffering from chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) typically lack p47-phox, p67-phox, p22-phox, or gp91-phox (reviewed elsewhere15 16). X-linked CGD patients bear mutations in CYBB, the gene encoding gp91-phox. In some of these patients, normal amounts of nonfunctional gp91-phox are found; such patients are designated X 91+ CGD patients.

Thus far, 6 X91+ CGD patients have been described (reviewed elsewhere17). Two of these patients have mutations leading to substitutions in the N-terminal part of gp91-phox (R54S and A57E), which affect heme binding and/or stable interaction with p22-phox.18,19The remaining 4 X91+ patients bear mutations in the cytosolic C-terminal part of gp91-phox. This region of gp91-phox is important for FAD and NADPH binding and is also involved in recruitment of cytosolic phox proteins. From sequence comparison between the C-terminal half of gp91-phoxand the ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase flavoenzyme family, the putative location of these FAD-binding and NADPH-binding domains within gp91-phox have been deduced.20-22 In 2 X91+ patients, there are substitutions in regions of gp91-phox predicted to be involved in NADPH binding: P415H and a replacement of residues 507-509 by HisIleTrpAla.23,24

The last 2 X91+ patients thus far described carry mutations in the cytosolic part of gp91-phox outside the putative binding regions for FAD or NADPH: a deletion of amino acids 488-497 and a D500G substitution.25,26 These mutations reside in a surface loop exposed to the cytosol as predicted by a structural model of gp91-phox.27 This suggests a role for this region of gp91-phox in the recruitment of cytosolic phox proteins. Indeed, the translocation of p47-phox and p67-phox to the plasma membranes of the neutrophils of the patient with the D500G substitution was abrogated in intact neutrophils as well as in the cell-free system.26The other patient has not been studied in this respect. Residue 500 of gp91-phox is the only residue to date that has been proven to be critical for interaction with the cytosolic oxidase components.

In the present report, we characterize an additional 4 X91+CGD patients. One of these patients has a substitution (T341K) in an FAD-binding region, the other patients have substitutions C369R, G408E, and E568K, which are predicted to be involved in NADPH binding or interaction with the cytosolic proteins p47-phox and p67-phox. We have studied the translocation of cytosolic proteins in these 4 patients. Indeed, the 3 latter patients have a strongly disturbed translocation of cytosolic phox proteins to the plasma membrane. Only the membranes harboring the T341K substitution supported a normal translocation, which indicates another cause of the oxidase defect in this patient, probably decreased FAD binding. With the help of these unique CGD patients we can verify predictions for the different binding regions derived from the structural model of gp91-phox and gain more insight into the complex interactions within the NADPH oxidase.

Patients and methods

Clinical history

All 4 patients suffer from the classical form of CGD, with frequent bacterialand fungal infections of the airways, skin, and lymph nodes. Two patients (MK, DG) presented with clinical manifestations at 8 months of life, the other 2 (JW, CE) at 3 years of age. All patients have been hospitalized at least 3 times. Surgical drainage of lymph nodes was performed in 2 patients (JW, MK). Microorganisms cultured were Salmonella from blood (DG), Staphylococcus aureusfrom blood (DG), Aspergillus fumigatus from the lungs (CE), andMycobacterium bovis from liquor (MK). Granulomatous lesions were found in the colon (CE) and in the cerebrum (MK). Treatment consisted of intravenous antibiotics during infectious episodes and prophylactic treatment with intracellular antibiotics (and itraconazole in MK and DG). Patient MK received granulocyte transfusions and interferon-gamma treatment during acute M bovis infection in the brain. In the family of JW, 2 maternal cousins with CGD have died. DG's mother has signs of lupus erythematosus.

Experimental procedures

Materials.

We used the following materials: guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate (GTP-γ-S) and NADPH (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany); reagents and molecular-weight markers for sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (BioRad Laboratories, Richmond, CA); and nitrocellulose sheets BA84 for Western blotting (Schleicher & Schull, Dassel, Germany). Antibodies used in this study were mAb 449 and 48, directed against p22-phox and gp91-phox, respectively.20 Rabbit antisera specific for either p47-phox or p67-phox were raised against synthetic peptides identical to the last 12 residues of the C-termini. Goat antibody against rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig), conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, was produced within our institute (CLB, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). We also used a chemiluminescence kit with luminol (ECL; Amersham International, Uppsala, Sweden); diagnostic films (X-Omat AR; Kodak, Rochester, NY); and the following lipids (Sigma; product numbers appear in brackets): L-α-phosphatidylcholine type 2-S from soybean, 14% (P5638), and L-α-phosphatidic acid, sodium salt, from egg yolk lecithin, 98% (P9511).

Classification of CGD patients.

Nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) slide tests with PMA were performed on the neutrophils of the 4 patients,29 and respiratory burst activity after stimulation with opsonized yeast particles or PMA was determined by the rate of oxygen consumption30 and chemiluminescence with lucigenin.31 Cytochromeb558 contents were determined by absorption spectroscopy32 and immunodetection on Western blot.28 For immunodetection, 2 μg of protein from a neutrophil membrane fraction were dissolved in SDS sample buffer (125 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8; 20% (w/v) SDS and 10% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol), loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide gel according to Laemmli,33 and then loaded in a gel apparatus (Mini-Protean II, BioRad). Western blotting was performed (Mini Trans-Blot cell, BioRad) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The nitrocellulose was stained for gp91-phoxand p22-phox with mAbs 48 and 449 and subsequently with goat-antimouse-Ig conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Detection was performed by a chemiluminescence kit (ECL, Amersham International).

Preparation of RNA and DNA.

Total RNA was purified from mononuclear leukocytes as described,34 and cDNA was synthesized with reverse transcriptase. The cDNA of the coding region of gp91-phox was amplified with PCR in 3 overlapping fragments as described,35,36 and it was subsequently sequenced (Sequenase Version 2.0 kit; US Biochemical, Cleveland, OH).37 Genomic DNA was isolated from circulating blood leukocytes37 of the 4 CGD patients.

Isolation and fractionation of leukocytes.

Human neutrophils were prepared on 4 different occasions from 20 to 50 mL of citrated blood from the 4 CGD patients after obtaining informed consent. Neutrophils from a healthy donor were isolated in parallel on each occasion as previously described.38 Subsequently, sonicated neutrophils were fractionated over a sucrose gradient as described.26

Translocation of cytosolic proteins in intact neutrophils.

Cells (20 × 106) of a patient and a healthy donor were incubated with PMA (100 ng/mL) or without PMA for 10 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then resuspended and sonicated in 1 mL of ice-cold oxidase buffer containing: sodium chloride (NaCl, 75 mmol/L); 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES, 10 mmol/L); sucrose (170 mmol/L); magnesium dichloride (MgCl2, 1 mmol/L); ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid (EGTA, 0.5 mmol/L); adenosine triphosphate (ATP, 10 μmol/L); and azide (2 mmol/L, pH 7.0) with GTPγS (5 μmol/L) and PMSF (100 μg/mL). After centrifugation (10 minutes, ×800 g), the sonicate was layered on a 15% sucrose gradient, as described previously,26 with MgCl2 (1 mmol/L); NaCl (40 mmol/L); EGTA, (0.5 mmol/L); and GTPγS (5 μmol/L). After centrifugation (45 minutes, ×100 000 g), 500 μL of plasma membranes were harvested. For immunodetection, 25 μL of membrane fraction were dissolved in SDS sample buffer (125 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.8; 20% (w/v) SDS and 10% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol) and were loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, according to Laemmli,33 in a gel apparatus (Mini-Protean II, BioRad). Western blotting was performed (Mini Trans-Blot cell, BioRad) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Detection of proteins was performed as described previously.26 When the blot was stained for 2 sets of proteins, the nitrocellulose was stripped, after the first staining, in 62.5 mmol/L Tris, pH 6.7; 2% SDS; and 100 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol.

Superoxide assay.

NADPH oxidase activity with neutrophil membranes and cytosol was measured as the SOD-sensitive reduction of cytochrome c in a spectrophotometer (Lambda 2, Perkin Elmer, Norwalk, CT). The contents of 6 cuvettes measured in parallel were stirred continuously and were thermostatted at 28°C. Plasma membranes (10 μg of protein) and cytosol (200 μg of protein) were incubated in oxidase buffer (0.8 mL) and cytochrome c (60 μmol/L). After 2 minutes of incubation, oxidase assembly was induced by addition of SDS (100 μmol/L) and GTP-γ-S (10 μmol/L). After 5 minutes, NADPH (250 μmol/L) was added, and the rate of cytochrome c reduction was measured at 550 nm.

Translocation of cytosolic proteins in the cell-free system.

Neutrophil plasma membranes (20 μg protein) were mixed with neutrophil cytosol (400 μg of protein) in oxidase buffer (1 mL). Subsequently, SDS (100 μmol/L) and GTP-γ-S (10 μmol/L) were added. After 10 minutes at room temperature, the mixture was loaded on a discontinuous sucrose gradient as previously described.26,39 40 NADPH oxidase activity of one-fifth part of the reisolated membranes was measured without cytosol, in the presence of SDS (100 μmol/L) and GTP-γ-S (10 μmol/L). After 2 minutes, NADPH (250 μmol/L) was added and the rate of cytochromec reduction was measured at 550 nm. In addition, the supernatant (50 μL) and the remaining four fifths of the reisolated membranes were analyzed by immunoblot for the presence of p47-phox, p67-phox, and cytochromeb558 subunits.

Oxygen consumption in plasma membranes without cytosol according to Koshkin and Pick.

Membrane protein (6 μg in 30 μL) was solubilized with 1-O-Octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (80 mmol/L) and buffer A (10 μL), which comprised: sodium phosphate (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4); EGTA (1 mmol/L); MgCl2 (1 mmol/L); sodium azide (NaN3, 2 mmol/L); dithiothreitol (1 mmol/L); and glycerol (20%).

Subsequently, the membranes were reconstituted with 4 μg each of L-α-phosphatidyl-choline and L-α-phosphatidic acid and diluted 8-fold in assay buffer: potassium (65 mmol/L), sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), MgCl2 (1 mmol/L), EGTA (1 mmol/L), NaN3(2 mmol/L), FAD (1 μmol/L), and SDS (30 μmol/L). The solution was allowed to stand on ice for 30 minutes. Oxygen consumption was measured with an oxygen electrode after the addition of NADPH (250 μmol/L).

Sequence alignment.

A multiple sequence alignment of the structurally known members of the ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR) family was performed by superimposing the structures with the program TOP.42 The sequence incorporation of the cytosolic C-terminal half of gp91-phox into the alignment profile of the FNR family was based on a previous sequence alignment of gp91-phox with FNR.27

Results

Diagnosis of CGD patients

The neutrophils of 4 patients (JW, CE, MK, and DG), stimulated with PMA or opsonized yeast particles, showed no respiratory burst as measured by oxygen consumption and chemiluminescence, which indicates a severe form of CGD. The cells of the mothers and/or sisters of patient JW, MK, and DG showed a mosaic pattern in the NBT slide test. These findings are compatible with an X-linked defect in these families. The cells of the only female patient (CE) showed a very low fraction of positive cells (4%) in the NBT slide test, which indicates an extreme lyonisation causing the CGD phenotype.

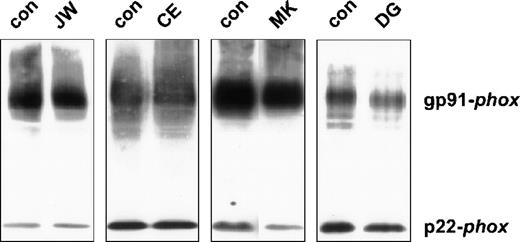

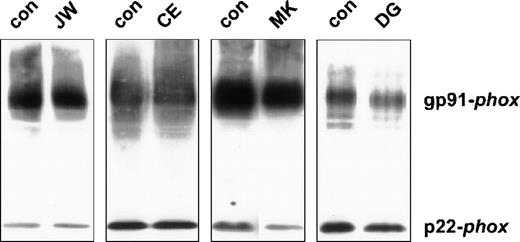

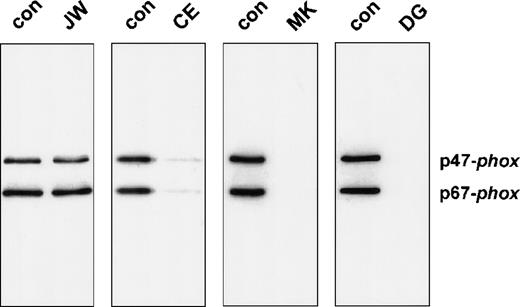

Because cytochrome b558 is typically absent in neutrophils of most patients with X-linked CGD, we measured the cytochrome b558 content in the patients' neutrophils by spectral and Western blot analysis. Interestingly, the optical spectrum of the patients' neutrophils showed an (almost) normal heme content (data not shown). On the immunoblot of the neutrophil membranes, both subunits of cytochromeb558 appeared to be present (see Figure1).

Western blot of neutrophil plasma membranes.

Plasma membranes (2 μg) were run on a 10% polyacrylamide minigel and blotted onto nitrocellulose. The blot was stained for gp91-phoxand p22-phox with mAbs 48 and 449, respectively, as previously described. The patients are indicated above the lanes. For each patient, material of a control donor was processed in parallel.

Western blot of neutrophil plasma membranes.

Plasma membranes (2 μg) were run on a 10% polyacrylamide minigel and blotted onto nitrocellulose. The blot was stained for gp91-phoxand p22-phox with mAbs 48 and 449, respectively, as previously described. The patients are indicated above the lanes. For each patient, material of a control donor was processed in parallel.

Superoxide production in the cell-free assay

To localize the cellular defect in NADPH oxidase activity, membrane and cytosolic fractions were prepared from the patients' neutrophils and studied in a cell-free oxidase assay. As shown in Table1, the membrane fraction of a control donor mixed with cytosol of the patients showed a normal rate of cytochromec reduction, whereas the membrane fractions of the patients mixed with control cytosol showed almost no superoxide production. Only the membranes of patient CE supported a low rate of superoxide production, probably caused by the small amount of unaffected cytochrome b558 present in 4% of the neutrophils in this extremely lyonized patient. This demonstrates that the defect in all patients is localized in a membrane-bound component of the NADPH oxidase, ie, in cytochrome b558.

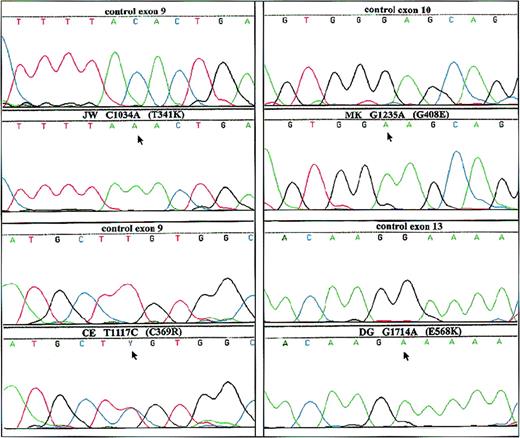

Genetic analysis of CGD patients

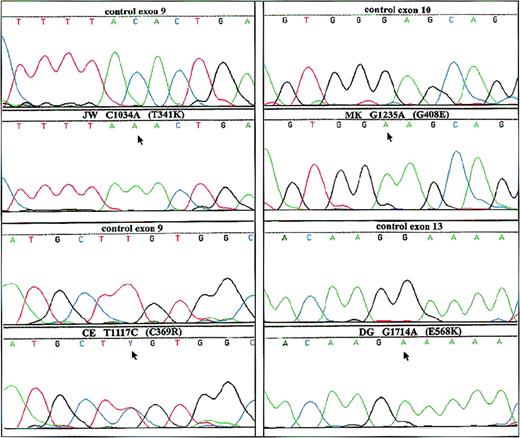

Because the defect in these patients was located in the membranes and was X-linked, we searched for mutations in gp91-phox. For this purpose, we amplified the coding region of the gp91-phox cDNA in 3 overlapping fragments and subsequently sequenced these fragments. We found 4 different point mutations in the 4 patients: JW (C1034A), CE (T1117C), MK (G1235A), and DG (G1714A), predicting amino acid substitutions T341K, C369R, G408E and E568K, respectively. These mutations were confirmed in the patients' genomic DNA after PCR amplification and subsequent sequencing (Figure2).

Analysis of genomic DNA from both the patients and a healthy control.

PCR products from each exon with intron boundaries and from the promoter region of CYBB were generated from genomic DNA obtained from circulating leukocytes and were analyzed by dye primer cycle sequencing. The figure shows the areas in which mutations were found in the patients. Patients are indicated by initials, nucleotide substitutions, and amino acid substitutions. Above each patient sequence, the normal sequence from the control is shown. Arrows indicate mutant sequence.

Analysis of genomic DNA from both the patients and a healthy control.

PCR products from each exon with intron boundaries and from the promoter region of CYBB were generated from genomic DNA obtained from circulating leukocytes and were analyzed by dye primer cycle sequencing. The figure shows the areas in which mutations were found in the patients. Patients are indicated by initials, nucleotide substitutions, and amino acid substitutions. Above each patient sequence, the normal sequence from the control is shown. Arrows indicate mutant sequence.

Translocation of p47-phox and p67-phox in neutrophils of CGD patients

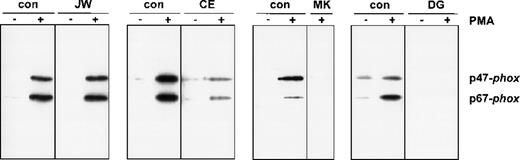

To investigate the functional effect of these substitutions in the cytoplasmic tail of gp91-phox, we studied the association of the cytosolic proteins with the plasma membranes of PMA-activated neutrophils. For this purpose, neutrophils of the patients and those of a healthy donor were incubated in parallel in the absence or presence of PMA, and subcellular fractions were isolated. Figure3 shows the Western blot of the supernatants and the plasma membranes of these neutrophils, stained for p47-phox and p67-phox. The figure clearly shows a strongly reduced translocation of both cytosolic oxidase components to the neutrophil membranes of the patients CE, MK, and DG upon stimulation with PMA. However, the neutrophils of patient JW showed a normal translocation.

Western blot analysis of plasma membranes of activated neutrophils.

Cells (20 × 106) were incubated with PMA (100 ng/mL) or without PMA for 10 minutes at 37°C. Fractionation of the cells was performed as previously described. PAGE (10%) was performed for the plasma membranes with comparable amounts of cytochrome b558. The blot was stained with rabbit antisera against p47-phox and p67-phox. The patients are indicated above the lanes. For each patient, material of a control donor was processed in parallel. The treatment (−PMA or +PMA) is also indicated above the lanes. From patient MK, we did not obtain enough neutrophils to investigate the unstimulated cells; therefore, only the +PMA lane is shown.

Western blot analysis of plasma membranes of activated neutrophils.

Cells (20 × 106) were incubated with PMA (100 ng/mL) or without PMA for 10 minutes at 37°C. Fractionation of the cells was performed as previously described. PAGE (10%) was performed for the plasma membranes with comparable amounts of cytochrome b558. The blot was stained with rabbit antisera against p47-phox and p67-phox. The patients are indicated above the lanes. For each patient, material of a control donor was processed in parallel. The treatment (−PMA or +PMA) is also indicated above the lanes. From patient MK, we did not obtain enough neutrophils to investigate the unstimulated cells; therefore, only the +PMA lane is shown.

Reprobing of the blots with antibodies against p22-phox and gp91-phox showed comparable amounts of these cytochromeb558 subunits between patients and controls (data not shown).

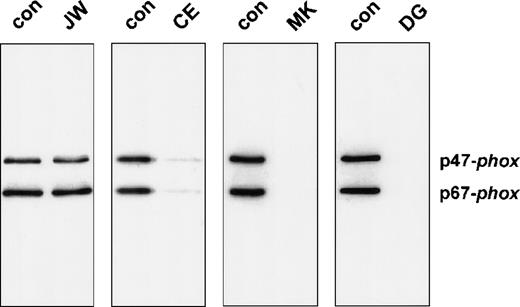

Effect of point mutations on oxide assembly

We also studied the neutrophil membranes of the 4 CGD patients for their ability to bind p47-phox and p67-phox in a cell-free translocation assay. The supernatant of the sucrose gradient and the reisolated membranes were analyzed on an immunoblot to determine the translocation of cytosolic oxidase components. Control membranes and the membranes of patient JW showed a significant association with p47-phox and p67-phox(Figure 4). In contrast, the neutrophil membranes of patients MK and DG did not contain appreciable amounts of cytosolic oxidase proteins. Only patient CE exhibited a very small amount of cytosolic proteins in the reisolated plasma membranes (6.5% of normal p67-phox translocation and 7.7% of normal p47-phox translocation, as determined by densitometry). This can be explained by the 4% of unaffected neutrophils in this extremely lyonized patient. The oxidase activity measured in the reisolated membranes is shown in Table 2. Similar to the cell-free system, only the membranes of patient CE generated a small amount of superoxide.

Western blot analysis of neutrophil membranes reisolated from the cell-free activation system.

The reisolated membranes were prepared as described in the legend of Table 2. Four fifths of these membrane samples were precipitated with 10% (w/v) trichloric acid and resuspended in sample buffer as previously described. After 10% PAGE, the proteins were blotted and stained for p47-phox and p67-phox.

Western blot analysis of neutrophil membranes reisolated from the cell-free activation system.

The reisolated membranes were prepared as described in the legend of Table 2. Four fifths of these membrane samples were precipitated with 10% (w/v) trichloric acid and resuspended in sample buffer as previously described. After 10% PAGE, the proteins were blotted and stained for p47-phox and p67-phox.

Oxygen consumption in neutrophil plasma membranes without cytosol

It has been described that relipidation of solubilized cytochromeb558 can elicit NADPH-dependent superoxide (O2−) production in the absence of cytosolic oxidase proteins,41 which suggests that cytochromeb558 contains the complete electron-transporting apparatus of the NADPH oxidase and that the cytosolic components merely function as activators. Therefore, we tested the neutrophil membranes of the patients for oxygen consumption in the absence of cytosol. For this purpose, membranes obtained from control donors or CGD patients were solubilized and activated with phospholipids in the presence of FAD and NADPH41 (Table 3). The neutrophil membranes of control donors exhibited significant oxygen consumption, whereas the neutrophil membranes of the CGD patients showed very low or no oxygen consumption.

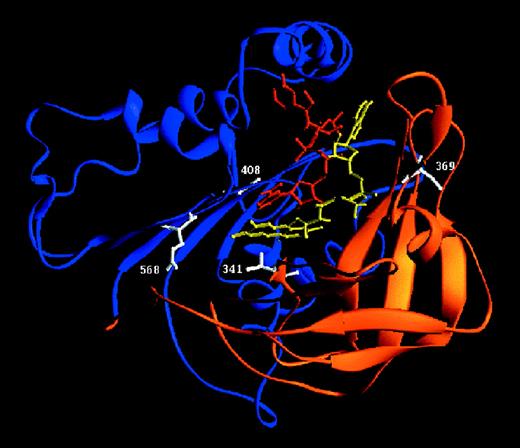

Location of amino acid substitutions in gp91-phox

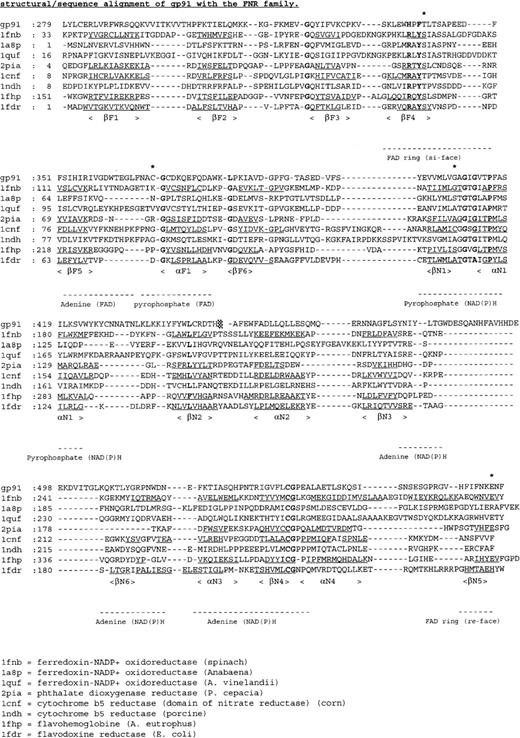

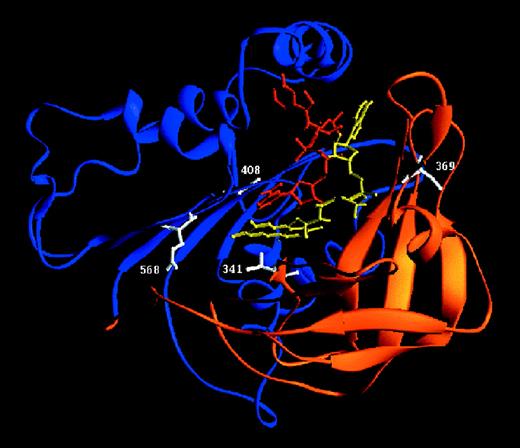

Figure 5 shows a sequence alignment of the cytosolic C-terminal domains of gp91-phox with members of the FNR family. From this alignment and the structural model of the globular portion of gp91-phox27 (Figure6), the putative location of the amino acid substitutions in the X-linked CGD patients can be deduced.

Multiple sequence alignment of the cytosolic C-terminal nucleotide binding domains of gp91-phox with members of the FNR family with known 3-dimensional structure.

The deduced amino acid sequence of gp91-phox is aligned with the amino acid sequences of ferredoxin NADP+ reductase from spinach (1fnb),43,Azotobacter vinelandii(1a8p),59 and Anabaena (1quf);60phthalate dioxygenase reductase from Pseudomonas cepacia(2pia);46 nitrate reductase from corn (1cnf);61 cytochrome b5 reductase from pig liver (1ndh);62 flavohemoglobin fromAlcaligenes eutrophus (1fhp);63 and flavodoxin reductase from Escherichia coli (1fdr).64 Secondary structure elements are underlined, conserved residues shown in bold, and mutated residues indicated by an asterisk.

Multiple sequence alignment of the cytosolic C-terminal nucleotide binding domains of gp91-phox with members of the FNR family with known 3-dimensional structure.

The deduced amino acid sequence of gp91-phox is aligned with the amino acid sequences of ferredoxin NADP+ reductase from spinach (1fnb),43,Azotobacter vinelandii(1a8p),59 and Anabaena (1quf);60phthalate dioxygenase reductase from Pseudomonas cepacia(2pia);46 nitrate reductase from corn (1cnf);61 cytochrome b5 reductase from pig liver (1ndh);62 flavohemoglobin fromAlcaligenes eutrophus (1fhp);63 and flavodoxin reductase from Escherichia coli (1fdr).64 Secondary structure elements are underlined, conserved residues shown in bold, and mutated residues indicated by an asterisk.

Ribbon diagram of the 3-dimensional model of the cytosolic part of gp91-phox.27

The schematic diagram was generated with Ribbons.65 The α-helices are depicted as cylinders and the β-sheets as arrows. The FAD-binding domain is drawn in orange, the NADPH-binding domain in blue, FAD in yellow, NADPH in red, and the mutated residues in white.

Ribbon diagram of the 3-dimensional model of the cytosolic part of gp91-phox.27

The schematic diagram was generated with Ribbons.65 The α-helices are depicted as cylinders and the β-sheets as arrows. The FAD-binding domain is drawn in orange, the NADPH-binding domain in blue, FAD in yellow, NADPH in red, and the mutated residues in white.

The T341K substitution in patient JW is located in the FAD-binding domain at the si-face of the flavin ring. Thr341 is part of a short sequence (HPFT, Figure 5) involved in binding the isoalloxazine moiety of FAD.20 Interestingly, this sequence is conserved in the plasma membrane iron reductase (FRE1) from yeast.43 However, in bacterial flavin reductase FRE proteins, the HPFT sequence is replaced by an RXYS motif,44which is also omnipresent in the FNR family (Figure 5). In FNR, the equivalent serine residue interacts with the N5 atom of the flavin ring45,46 and is directly involved in the reduction of NADP+.47

The C369R substitution in patient CE is also situated in the FAD-binding domain (Figure 6). Cys369 resides in a surface loop and is next to the strictly conserved Gly370 (Figure 5). This glycine is at the beginning of a helix, proposed to be important for interaction with the pyrophosphate moiety of FAD.48

Discussion

Cytochrome b558 of human phagocytes is a membrane-bound heterodimer of p22-phox and gp91-phox. The cytochrome has an NADPH-binding site and bears a flavin group that acts as the initial acceptor of a pair of electrons from NADPH.20-22 Two heme groups embedded in the flavocytochrome mediate the 1-electron transfer from FAD to molecular oxygen, thus generating superoxide (O2-).50Sequence-homology studies between the C-terminal half of gp91-phox and the ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase flavoenzyme family suggest that both FAD and NADPH are bound by specific domains within this part of gp91-phox.20-22

CGD patients with X-linked, cytochromeb558-positive CGD (X91+) can be very helpful in verifying the various binding domains in gp91-phox. In this study we have characterized the defects in 4 X91+CGD patients. We found 4 different point mutations in the gene encoding gp91-phox, leading to amino acid substitutions in the cytosolic C-terminal part of gp91-phox.

Patient JW carries a T341K substitution in the FAD-binding site of gp91-phox. This mutation does not result in a lower amount of cytochrome b558, which points to a proper folding of the gp91-phox polypeptide chain. In PMA-stimulated neutrophils of this patient, the translocation of p47-phox and p67-phox was unaffected (Figure 3). Also in the cell-free system the translocation appeared to be normal. These data, and the fact that the NADPH oxidase is inactive (Table 1 and 2), suggest that the defect in this patient is not due to an impaired regulation of cytochrome b558 activity by the cytosolic oxidase subunits, but is restricted to a subsequent step. Based on mutagenesis studies of FNR47 and flavin reductase,44 it is obvious that introduction of a positive charge at position 341 in gp91-phox impairs the efficient hydride transfer between NADPH and FAD. The T341K substitution probably influences the correct stacking of nicotinamide and isoalloxazine rings and most likely also the redox properties of the flavin. The lack of NADPH oxidase activity in this patient is probably not due to weak binding of the FAD. This may be derived from the fact that proper binding of FAD is essential for normal gp91-phox expression.51

The other 3 X91+ CGD patients studied in this report carry C369R, G408E, and E568K substitutions. In contrast to the first patient, translocation of p47-phox and p67-phox to the plasma membranes upon activation of the neutrophils of these patients was strongly disturbed (Figure 3). Also, in the cell-free system no appreciable amounts of p47-phox and p67-phox were detected in the membrane fractions (Figure 4). Thus far, only 1 other X91+ CGD patient has been described with a disturbed translocation of both cytosolic proteins. This patient is carrying a D500G substitution, situated in an exposed protein loop, as predicted by the structural model of the C-terminal half of gp91-phox. As can be seen from the sequence alignment in Figure 5, this surface loop is absent in other members of the FNR family. The disturbed translocation of cytosolic oxidase components in this patient is indicative for a role of the NADPH-binding domain of gp91-phoxin p47-phox and/or p67-phox recognition. This idea corresponds with the notion of an additional NADPH-binding domain in p67-phox.52

The C369R substitution in patient CE described here also resides in a surface loop (Figure 6). However, this loop is located in the FAD-binding domain, which suggests that this domain is also involved in the translocation process. Based on the structural properties of the FNR family,48 the loop comprising residue 369 is supposed to be flexible. Therefore, defective translocation of cytosolic proteins in patient CE is most simply explained by an electrostatic repulsion mechanism. On the other hand, the C369R substitution is also close to helix F1, which is involved in binding the pyrophosphate moiety of FAD. This might explain the lack of electron transfer in solubilized plasma membranes of this patient.

In patient MK, the G408E substitution is localized between βN1 and αN1, close to the GXGXXP fingerprint sequence (Figure 5) for binding the pyrophosphate moiety of NADPH.20 48 Although Gly408 is predicted to be buried and not likely a binding site for 1 of the cytosolic proteins, introduction of a more bulky acidic residue at this position could perturb normal NADPH binding through electrostatic repulsion of the pyrophosphate group and/or introduce local structural changes in the NADPH-binding domain that are transmitted to the protein surface. Such structural changes might also hamper NADPH binding, leading to impaired oxygen consumption of solubilized plasma membranes, but apparently also disturb the binding sites for p47-phoxand/or p67-phox.

The substitution E568K in patient DG resides in the extreme C-terminal region of gp91-phox, implicated as a contact point for p47-phox.53-55 These published studies were performed with (inhibitory) peptides in the cell-free system. However, recently Dinauer et al56 used a different approach: In a human myeloid leukemia cell-line, the gp91-phox gene was knocked out by targeted disruption. Then site-directed mutagenesis and transfection of gp91-phox was used to probe the role of the C-terminus of gp91-phox in NADPH oxidase activity.49 Despite the expectations, none of the substitutions introduced in the region 560-570 of gp91-phox had a dramatic effect on oxidase activity in intact cells, but several substitutions were associated with reduced expression of gp91-phox.

In patient DG, the E568K substitution was associated with normal amounts of both subunits of cytochrome b558 (Figure1). This contrasts with the in vitro mutagenesis studies,49where C-terminal replacements resulted in poor protein expression. Nonetheless, in patient DG almost no oxidase activity was measured. Also, the translocation of p47-phox and p67-phox in PMA-stimulated neutrophils, as well as in the cell-free system, was abrogated. In addition, electron transfer in the solubilized neutrophil membranes of this patient was also disturbed. These results imply that Glu568 of gp91-phox is indeed required for oxidase activity and for the binding of the cytosolic phox proteins. In relation to this observation, it is interesting to note that in spinach FNR57 and Anabaena FNR,58 the equivalent C-terminal glutamic acid is critical for rapid electron transfer with the iron-sulfur cluster of ferredoxin, without appreciably affecting complex formation.

In conclusion, this paper reports on 4 X91+ CGD patients with unique single amino acid substitutions. These substitutions are localized in different regions of the FAD-binding and NADPH-binding domains of gp91-phox and cause strongly impaired superoxide production without affecting gp91-phox expression. Because 3 of these amino acid substitutions disturb the binding of cytosolic NADPH oxidase components to the membrane-bound gp91-phox, this points at an intimate relation between domains of gp91-phox involved in electron transfer and those involved in p47-phox/p67phox binding.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr U. Ermler for providing us with the coordinates of the flavohemoglobin structure (1fhp) and Dr A.W. Segal for the coordinates of the structural model of the globular portion of gp91-phox.

Supported by grants from The Netherlands Fund for Preventive Medicine (Praeventiefonds) and from the German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft) to C.M..

Reprints:D Roos, Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, Plesmanlaan 125, 1066 CX Amsterdam, The Netherlands; e-mail: d_roos@clb.nl.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.