Abstract

In 99 adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) who received highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (including 2 nucleoside analogues and 1 or 2 protease inhibitors) for 1 year, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including memory and naive subsets) increased similarly among patients with sustained plasma viral load decrease, transient decrease, or no decrease. A linear correlation was observed between the decrease in serum β2-microglobulin concentration (an independent surrogate marker of HIV disease) and the increase in peripheral blood T-cells (CD4+ and CD8+) counts. In vitro, HIV protease inhibitors indinavir and saquinavir (but not nucleoside analogues) enhanced the survival of patients' peripheral blood T cells at doses that are at least 30-fold lower than those required for achieving 90% viral inhibition in the same cultures. This enhanced T-cell survival (which is similar for CD4 and CD8 cells) was associated with a restoration of T-cell proliferative response to immune stimuli. However, neither TCR/CD3-ligation– nor Fas-ligation–triggered apoptosis was affected by either of the 2 protease inhibitors. A reduction in apoptosis observed after prolonged culture of patient T cells in the presence of the protease inhibitors could result from restored T-cell proliferation. These findings explain the discrepancies between virologic and immunologic responses that are increasingly reported in patients receiving HAART, and may provide insights into the pathogenesis of HIV infection.

Treatment of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), including at least 1 protease inhibitor (PI) allows dramatic decrease in plasma and tissue HIV RNA load, as well as quantitative and functional recovery of peripheral CD4+ T cells in the majority of patients,1-4 resulting in a significant reduction in AIDS-related morbidity and mortality.5 However, in vivo mechanisms governing CD4+ T-cell improvement under HAART are still controversial.6-9 Although several recent studies have reported the lack of association between increase in CD4 count and decline in viral load under HAART,10-12 a systematic study addressing the recovery of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with regard to different patterns of virologic response under HAART is still lacking.

In this study, we examined the kinetics of T-cell recovery in relation to the patterns of viral load response in patients treated with HAART and the in vitro effects of HIV PIs on the survival, proliferation, and apoptosis of HIV-infected patient's peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to immune stimuli.

Patients and methods

Patients

Ninety-nine HIV-seropositive adults were enrolled in an open-label trial of HAART. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This antiretroviral regimen consisted of 1 PI (indinavir, 2400 mg/d) or 2 PIs (ritonavir, 200 mg/d plus saquinavir, 1200 mg/d) associated with 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) (lamivudine [300 mg/d] and stavudine [60 or 80 mg/d] or zidovudine [500 mg/d]). Patients had never received any HIV PIs, had a CD4 count of less than 500 cells/μL, and had a plasma HIV RNA load of at least 10 000 copies/mL (Quantiplex HIV-1 3.0; Bayer Emeryville, CA). Patients were assessed every 2 months until 12 months. Whole heparinized blood and EDTA-treated plasma samples were taken at enrollment and every 2 months thereafter for immunologic and virologic assessments. Patients who have a sustained plasma viral load decrease (less than 1000 Eq copies/mL) will be defined as virologic responders; patients who have an initial decrease (less than 1000 Eq copies/mL) but have a viral load reincrease (at least 1000 Eq copies/mL) before 1 year will be defined as virologic transient responders; and patients who remain over 1000 Eq copies/mL throughout the 12 months will be defined as virologic nonresponders.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts as well as their naive (CD45RO+ or CD45RA+/CD62L−) or memory (CD45RA+/CD62L+) subsets were assessed on fresh whole blood samples by flow cytometry analysis (FACScan, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). A panel of monoclonal antibodies to the following T-cell surface markers was used: CD3-PerCP, CD4-FITC, CD8-PE, CD45RO-PE, CD45RA-PE, CD62L-FITC, CD4-PerCP, and CD8-PerCP (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont-de-Claix, France).

Plasma human immunodeficiency virus RNA quantitation assay

Plasma HIV RNA concentration was measured in EDTA-treated plasma samples (frozen only once) by a commercial Quantiplex HIV-1 RNA quantitation kit 3.0 (detection threshold of 50 Eq copies/mL) (Bayer) performed according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Serum β2-microglobulin assay

Sera were collected at baseline and at months 6 and 12; serum samples were protected from light and stored at −20°C until use. The β2-microglobulin concentrations were measured by a commercial radioimmunoassay kit (β2-Microglobulin RIA, Immunotech, Marseille, France). Serum β2-microglobulin values in healthy people ranged from 1.10 to 2.40 mg/L.

Human immunodeficiency virus inhibition and cell survival

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) freshly isolated from whole blood of untreated HIV-1–infected patients or healthy donors were resuspended at 106 per milliliter in RPMI 1640 human lymphocyte culture medium (HLCM) containing 20% heat-inactivated human AB serum, nonessential amino acid, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer. Then, 2 × 106 PBMCs were seeded in 24-well tissue culture plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and were stimulated with 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (Becton Dickinson) plus 5 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in the absence or the presence of serial dilutions (0.1-1000 nmol/L) of indinavir (obtained from Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, PA), saquinavir (obtained from Roche Products, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, UK), zalcitabine (Roche), didanosine (obtained from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Fontenay sous Bois, France), or stavudine (Bristol-Myers Squibb). Indinavir and saquinavir powders were initially dissolved in 50:50 ethanol/water (10 mmol/L at 25°C) as indicated by suppliers. Further drug dilutions were performed with water and culture medium, whereas the dissolving agent (50:50 ethanol/water) alone was diluted in parallel and served as the control. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in humidified air at 5% CO2. After 48 hours, stimulated PBMCs were washed and resuspended at 106 per milliliter in HLCM containing the same concentrations of the drugs plus 20 IU/mL interleukin 2 (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) for an additional 14-day culture. The culture mediums were changed every 2 to 3 days keeping the cultures at a viable cell density ≤ 2 × 106 per well in a constant volume of 2 mL per well. At each time point, viable cell counts were determined by trypan blue exclusion and supernatants were harvested for testing HIV-1 p24 antigen by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Organon Teknika, Boxtel, The Netherlands). The percentage viral inhibition was determined by the reduction of p24 production (at peak time point) in patients' PBMC cultures in the presence of different concentrations of each of the drugs compared with patients' PBMC cultures alone. Cell survival was determined by net gain of total expanded viable cells in the presence of different concentrations of each of the drugs compared with PBMC cultures alone.

Proliferation assay

Freshly isolated patients' or donors' PBMCs were resuspended at a cell density of 5 × 105/mL in HLCM and seeded in quadruplicate in 96-well round-bottomed microtitre plates (Nunc) containing 105 PBMCs per well. Cells were stimulated with 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies plus 5 ng/mL PMA in the absence or the presence of serial dilutions (0.1-1000 nmol/L) of indinavir or saquinavir as described above. The microtitre plates were placed in a cell incubator in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 4 days. Cells were pulsed with 0.037 MBq (1 μCi) per well [3H]-thymidine (Amershan, Aylesbury, UK) for the final 16 hours of the 4-day culture. Then, cells were harvested on glass fiber filters by an automated multisample harvester and filters were put in tubes with liquid scintillation fluid and counted on a β-scintillation counter.

Apoptosis assay

To test TCR/CD3-ligation–induced apoptosis, freshly isolated patients' or donors' PBMCs were stimulated overnight with 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 antibodies in the absence or the presence of indinavir or saquinavir, as indicated, concentrations. To measure Fas-ligation–triggered apoptosis, anti-CD3/PMA–stimulated patients' or donors' PBMCs were cultured in the absence or the presence of indinavir or saquinavir for 10 days. Cells were then stimulated overnight with 100 ng/mL anti-Fas monoclonal antibodies (clone 7C11, Immunotech). Apoptosis measurement was also performed in freshly isolated PBMCs and cultured PBMCs stimulated with anti-CD3/PMA (see cell survival section). Apoptosis was measured by propidium iodide and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled annexin V, a phospholipid binding protein that preferentially binds to phosphatidylserine exposed at cell surface in the early phase of apoptosis, using a commercially available kit (Immunotech). Cells that are negative for prodidium iodide and positive for annexin V will be identified as apoptotic cells, whereas those positive for both prodidium iodide and annexin V are secondary necrotic cells.

Statistical analysis

Baseline and follow-up data of patients receiving HAART were compared by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Data between different groups of patients were compared by the Mann-Whitney test.

Results

Study patients

A total of 99 HIV-1 seropositive patients (65 pretreated with nucleoside analogues and 34 naive) were enrolled in this study. Baseline median CD4 and CD8 counts were 167 and 810 cells/μL, respectively, and median plasma HIV RNA concentration was 4.21 log10 equivalent (Eq) copies per milliliter. Twenty patients had a clinical AIDS-defining illness before entry. All patients received HAART for a minimum of 1 year. The initial HAART regimen was made of 2 NRTIs (lamivudine, 300 mg/d and stavudine, 60 or 80 mg/d) and 1 PI (indinavir, 2400 mg/d). Indinavir was replaced by ritonavir (200 mg/d) plus saquinavir (1200 mg/d) in 17 cases and stavudine was replaced by zidovudine (500 mg/d) in 7 cases. No new AIDS event was diagnosed over this 1-year follow-up period. The characteristics of the 99 patients and their CD4 counts and viral load values at baseline and at 1 year under HAART were summarized in Table1.

Plasma viral load suppression and CD4+ T-cell recovery

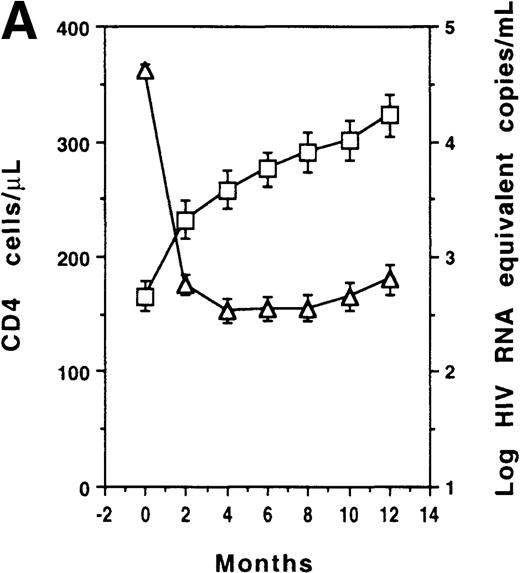

CD4 counts increased and plasma viral load decreased at month 2 (P < .001) in the whole group (Figure1A). However, no significant correlation was found between plasma viral load changes and CD4 count changes at any time point. Three subgroups of patients were identified according to their plasma viral load outcomes: virologic responders (n = 59) who had a sustained plasma viral load decrease (less than 1000 Eq copies/mL); virologic transient responders (n = 23) who had an initial decrease (less than 1000 Eq copies/mL) but had a viral load reincrease (at least 1000 Eq copies/mL) before 1 year; and virologic nonresponders (n = 17) who remained greater than 1000 Eq copies/mL throughout the study period (Figure 1B). CD4 counts increased at month 2 in virologic responders (P < .001); counts increased similarly in transient responders (P = .003) and nonresponders (P = .016) (Figure 1C). In the 59 virologic responders, CD4 counts increased (at least 20%) in 55 cases (93%), remained unchanged (less than 20% and more than −20%) in 3 cases, and decreased (no more than −20%) in 1 case. In the 23 virologic transient responders, CD4 counts increased in 21 cases (91%) and remained unchanged in 2 cases. Among the 17 virologic nonresponders, CD4 counts increased in 15 cases (88%) and remained stable in 2 cases.

T-cell recovery and viral suppression under HAART.

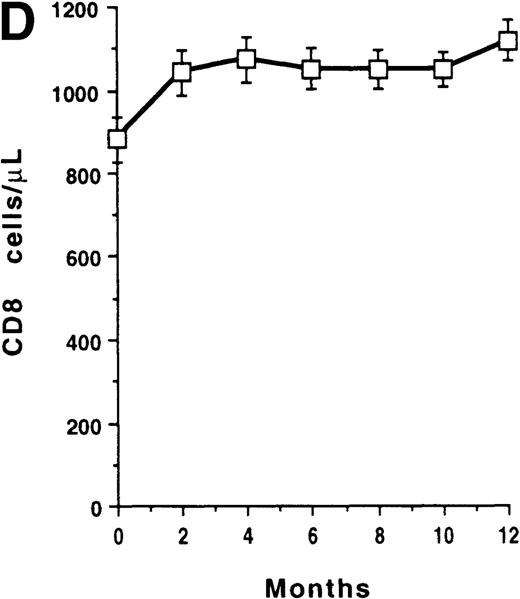

Evolution of CD4 counts (□) and plasma viral loads (▵) in the whole group of patients (A). Evolution of plasma viral loads (B) and CD4 counts (C) in virologic responders (○), transient responders (▴), and nonresponders (▪). Evolution of CD8 counts in the whole group (D). Correlation between CD8 count change and baseline CD8 count (E). Evolution of CD8 counts in patients with a baseline CD8 count less than 1000 cells/μL (○, virologic responders; ▴, transient responders; and •, nonresponders) (F). Data were expressed as the mean ± SE of each group of patients. Threshold for plasma viral load measurement by Quantiplex assay was 50 HIV RNA equivalent (Eq) copies per milliliter. For the purpose of calculation, this value was assigned when the plasma viral load became undetectable.

T-cell recovery and viral suppression under HAART.

Evolution of CD4 counts (□) and plasma viral loads (▵) in the whole group of patients (A). Evolution of plasma viral loads (B) and CD4 counts (C) in virologic responders (○), transient responders (▴), and nonresponders (▪). Evolution of CD8 counts in the whole group (D). Correlation between CD8 count change and baseline CD8 count (E). Evolution of CD8 counts in patients with a baseline CD8 count less than 1000 cells/μL (○, virologic responders; ▴, transient responders; and •, nonresponders) (F). Data were expressed as the mean ± SE of each group of patients. Threshold for plasma viral load measurement by Quantiplex assay was 50 HIV RNA equivalent (Eq) copies per milliliter. For the purpose of calculation, this value was assigned when the plasma viral load became undetectable.

CD8+ T-cell recovery

The mean CD8+ T-cell count of the whole group increased at month 2 (P < .001) and reached a maximum gain of 238 cells/μL at 1 year (Figure 1D). The 1-year change of CD8 count was inversely correlated with baseline level of CD8 count (r = −0.534, P < .001) (Figure 1E), but was independent of both the baseline level and the 1-year change of plasma viral load (data not shown). Among the 71 patients who had an increase in their CD8 cells (consistent gain of at least 20%), 70 had a CD4 count increase and 1 had an unchanged CD4 count. Patients were then partitioned according to their baseline CD8-count levels (less than 1000 cells/μL, n = 62; at least 1000 cells/μL, n = 37). Among patients with a baseline CD8 count of less than 1000 cells/μL, CD8 cells increased at month 2 in the 35 virologic responders (P < .001); it increased similarly in the 14 transient responders (P = .019) and in the 13 nonresponders (P = .002) (Figure 1F). In addition, there was a significant correlation between CD8 count changes and CD4 count changes at 1 year (r = 0.427, P < .001). In contrast, the mean CD8 count of patients with a baseline CD8 count of at least 1000 cells/μL remained unchanged.

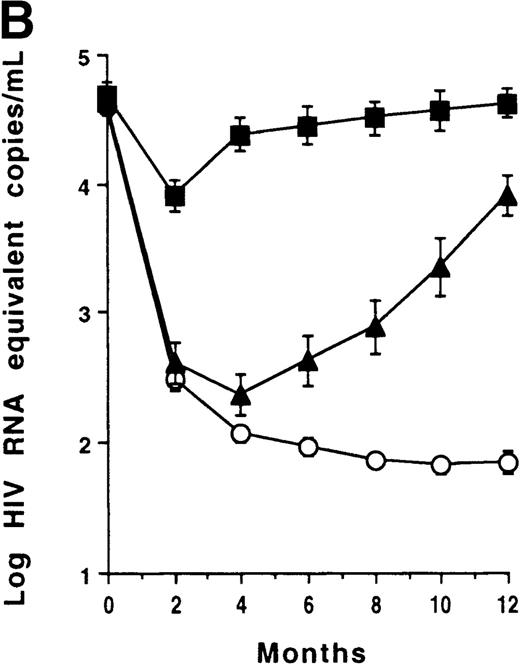

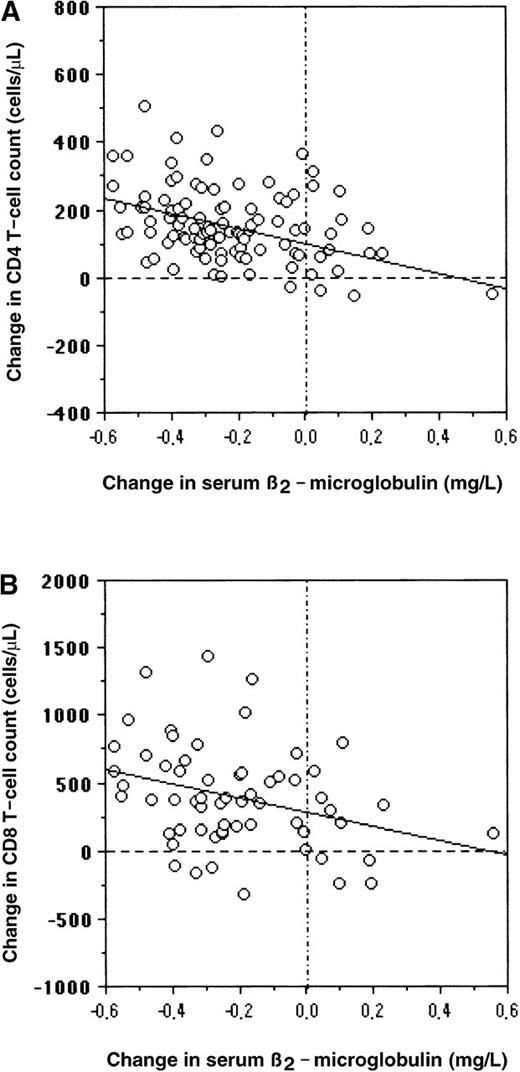

Normalizations of T-cell compartment and serum soluble T-cell activation marker

Memory or naive CD4+ T cells increased at 6 months (P < .01) and 1 year (P < .001) under HAART. Memory or naive CD4 cells had similar expansion in the 3 subgroups of patients with different patterns of plasma viral load response. In the patients with low baseline CD8 counts, a similar increase of memory or naive CD8 cells was also observed at 6 months (P < .05) and 1 year (P < .01) in the 3 subgroups. Serum β2-microglobulin concentrations decreased at 6 months (P < .01) and 1 year (P < .001) in virologic responders, transient responders, and nonresponders. No significant difference among the 3 subgroups was found for baseline levels of memory/naive CD4 and CD8 cells or for baseline levels of serum β2-microglobulin concentrations (Table2). The 1-year change in serum β2-microglobulin concentration was inversely correlated with the 1-year change of CD4 counts (r = −0.418,P < .001) in the overall group (Figure2A), as well as with the 1-year change of CD8 count (r = −0.318,P = .012) in the 62 patients with low baseline CD8 counts (Figure 2B). Serum β2-microglobulin concentrations decreased at month 6 (mean change −0.85 mg/L,P < .001) and at 1 year (−1.04 mg/L,P < .001) in the 91 patients who had a CD4 count increase (persistent gain ≥ 20%) independently of their virologic response. In contrast, there was no modification in the mean serum β2-microglobulin concentration at any time point in the 9 patients whose CD4 counts remained stable or decreased under HAART. Among patients with a baseline CD8 count less than 1000 cells/μL, serum β2-microglobulin concentrations also decreased at month 6 (−0.84 mg/L, P < .001) and at 1 year (−1.09 mg/L, P < .001) in the 53 patients who had a CD8 count increase, whereas no significant modification was observed in the 10 patients who did not increase their CD8 counts during the follow-up period.

Serum β2-microglobulin concentration and CD4 counts.

Correlation between serum β2-microglobulin concentration and change in CD4 counts in the whole group (A) or change in CD8 counts in the 62 patients with baseline CD8 counts less than 1000 cells/μL (B).

Serum β2-microglobulin concentration and CD4 counts.

Correlation between serum β2-microglobulin concentration and change in CD4 counts in the whole group (A) or change in CD8 counts in the 62 patients with baseline CD8 counts less than 1000 cells/μL (B).

Viro-immunologic responses in naive and pretreated patients

At entry, naive patients had a higher plasma viral load and CD4 count levels than pretreated patients (median 4.9 vs 4.4 log HIV-1 RNA Eq copies/mL, P = .013 and mean 212 vs 143 CD4 cells/μL,P = .006), whereas the baseline CD8 count and serum β2-microglobulin concentration did not differ significantly in naive and pretreated patients. Under HAART, plasma viral load decreased more profoundly in naive patients than in pretreated patients (6 months mean −2.7 vs −1.7 log Eq copies/mL, P < .001; 1 year −2.3 vs −1.5 log Eq copies/mL, P = .002); on the other hand, CD4 counts, CD8 counts (of patients with low baseline CD8 counts), and serum β2-microglobulin concentrations decreased equally in naive and pretreated patients from baseline to months 6 and 12.

Effects of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors on T-cell survival and viral inhibition

After isolating PBMCs from fresh blood samples of 10 untreated HIV-1–infected patients with CD4 count between 200 and 300 cells/μL and plasma viral load between 4 and 5 log10 Eq copies/mL, indinavir or saquinavir was added at the same time as 2 × 106 cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 antibodies plus PMA; the drug was then re-added each other day with fresh culture medium until day 16. In PBMCs taken from 10 noninfected donors, 2 × 106 cells at baseline grew up to mean (± SD) 151 (± 32) × 106 cells after 16 days of culture in the absence of PI. Neither the survival nor the phenotype of noninfected donors' PBMCs was affected by either of the 2 PIs (data not shown). PBMCs of the 10 untreated patients increased moderately from 2 × 106 cells at baseline increased to mean 6.2 (± 5.7) × 106 cells at day 16 of culture in the absence of PI. In contrast, under either of the 2 PIs, patients' PBMC survival increased dramatically with a net gain ≥ 50 × 106 viable cells at drug concentrations ranging from 1 to 1000 nmol/L (peak: 10-100 nmol/L), whereas viral replication (measured by p24 production in culture supernatants) was suppressed by ≥ 90% at drug concentrations ranging from 30 to 300 nmol/L to 1000 nmol/L. Data from 3 representative patients (patients A, B, and C, respectively) are shown in Figure3. Phenotype analysis of patients' PBMCs at the end of the culture period revealed that both CD4+and CD8+ T cells were equally expanded under either of the 2 PIs (data not shown).

Effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell survival and HIV-1 inhibition.

Dose-dependent effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell survival (○) and HIV-1 inhibition (▵). Results show the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures of net gain of viable cells or percentage HIV-1 p24 inhibition in 3 representative PBMCs of untreated patients A (A and B), B (C and D), and C (E and F) in the absence or the presence of different concentrations of each of the 2 protease inhibitors.

Effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell survival and HIV-1 inhibition.

Dose-dependent effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell survival (○) and HIV-1 inhibition (▵). Results show the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures of net gain of viable cells or percentage HIV-1 p24 inhibition in 3 representative PBMCs of untreated patients A (A and B), B (C and D), and C (E and F) in the absence or the presence of different concentrations of each of the 2 protease inhibitors.

In 15 HAART-treated patients (5 virologic responders, 5 transient responders, and 5 nonresponders), effective concentrations of PIs enhancing T-cell survival and suppressing viral replication were further evaluated in vitro. In the presence of either of the 2 PIs, survival was increased in all patients' PBMCs tested; this occurred independently of their patterns of virologic response to HAART. The range of effective doses (1-3 log10) was inversely correlated with the CD4 cell count (P = .004). On the other hand, viral replication was detected in 1 of 5 virologic responders, 4 of 5 transient responders, and all 5 nonresponders. Among p24-positive cultures, the effective dose for 90% viral inhibition was high (≥ 214 nmol/L or ≥ 169 nmol/L for indinavir or saquinavir) in 2 of 4 transient responders and 1 of 5 nonresponders, whereas it was low (≤ 64 nmol/L or ≤ 35 nmol/L for indinavir or saquinavir) in all other samples, in which p24 was measured (Table3).

The effects of NRTIs (including didanosine, zalcitabine, and stavudine) on T-cell survival and viral inhibition were also evaluated in vitro as control. Apart from their expected antiviral activities, the cell survival of patients' PBMCs or healthy donors' PBMCs was not modified by didanosine or stavudine and was decreased by zalcitabine (data not shown).

Effects of human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitors on T-cell proliferation and apoptosis

Proliferative response to anti-CD3/PMA stimulation of PBMCs from untreated patients or healthy donors was measured by [3H]-thymidine uptake after 4 days of culture in the absence or the presence of different concentrations of each of the 2 PIs. In the absence of drug, [3H]-thymidine uptake of patients' PBMCs was suppressed by 76% when compared with donors' PBMCs. Under both PIs, [3H]-thymidine uptake of donors' PBMCs remained unchanged, whereas the low proliferative response of patients' PBMCs without PI was restored by effective concentrations 1 to 1000 nmol/L of each of the 2 PIs (Figure4A and B). Apoptosis of patients' or donors' PBMCs upon TCR/CD3 ligation with anti-CD3 antibodies was not affected by any dose of indinavir or saquinavir (Figure 4C and D). Apoptosis of mitogen-stimulated patients' and donors' PBMCs upon Fas receptor (CD95) cross-linking with anti-Fas antibodies was also not affected by any dose of the 2 PIs (Figure 4E and F). Furthermore, apoptosis was not affected by preincubating (4-16 hours) T cells with the 2 PIs before anti-CD3 or anti-Fas stimulation (data not shown). A reduction in apoptosis was observed solely after a 14-day culture of patient PBMCs in the presence of each (100 nmol/L) of the 2 PIs (Table4).

Dose-dependent effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell proliferation and apoptosis.

Results represent the mean ± SD of [3H]-thymidine uptake (A and B) and percentage apoptotic cells upon TCR/CD3 ligation with anti-CD3 antibodies (C and D) or upon Fas ligation with anti-Fas antibodies (E and F) in 10 healthy donor PBMCs (□) and 10 untreated HIV-1 patient PBMCs (▪).

Dose-dependent effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell proliferation and apoptosis.

Results represent the mean ± SD of [3H]-thymidine uptake (A and B) and percentage apoptotic cells upon TCR/CD3 ligation with anti-CD3 antibodies (C and D) or upon Fas ligation with anti-Fas antibodies (E and F) in 10 healthy donor PBMCs (□) and 10 untreated HIV-1 patient PBMCs (▪).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that, under HAART, CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocyte compartments were both involved in immunogic recovery in naive patients, as well as in pretreated ones. However, no quantitative correlation was found between T-cell recovery and virologic response. Among the 99 treated patients, 40 (40%) failed to achieve sustained viral suppression. Paradoxically, as many as 91 (91%) cases had a sustained CD4 cell increase achieved paradoxically, whereas 7 stabilized their CD4 counts and only 1 had a minor decrease in his CD4 count. Interestingly, increases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (including memory and naive subsets) were found to be linearly correlated with the decline in serum β2-microglobulin concentration (a nonspecific marker of immune activation) (Figure 2). In HIV-infected individuals, increased serum β2-microglobulin is the most stable marker of immune stimulation/activation in vivo.13 A high level of serum β2-microglobulin has been reported to correlate with a rapid progression to AIDS and is thus generally accepted as an independent marker of HIV disease prognosis.14-16 It would be conceivable that the decline in serum β2-microglobulin could simply be the result of the decreasing viral load of lymphoid organs (corresponding to a decrease in viral antigen-driven stimulation) under HAART. However, serum β2-microglobulin declined equally in virologic responders, transient responders, and nonresponders (Table 2). This disassociation between immunologic and virologic responses suggests that a direct mechanism might be involved in the overall immune recovery under HAART. In this regard, it is worthy to note that in 44 HIV-1–infected patients treated by prednisolone (a potent immune regulatory drug with antiapoptotic activity17) for 1 year, CD4 count increase and serum β2-microglobulin decrease were both observed in the absence of any modification of plasma viral load.18

Results from this in vitro study demonstrate that PIs (the key component of the HAART regimen), but not NRTIs (the additional components of HAART), enhance the survival of HIV-1–infected patients' T lymphocytes by restoring their responsiveness to immune stimuli with an effective dose at least 30-fold less than that required for achieving 90% viral inhibition in the same culture. This implies that patients experiencing a lack of virologic response to HAART might have a lymphoid tissue PI concentration that is insufficient or not capable to suppress viral replication but is, however, effective for restoring T-cell responsiveness in activation sites. This is in keeping with the observation that most virologic nonresponders (4 of 5 cases) remained sensitive to viral inhibition by PIs in vitro (Table 3). In this setting, it has been shown that virologic failure may occur in the absence of drug-resistance mutations19; it has also been shown that virologic nonresponders had low plasma drug concentrations compared with responders who had higher plasma drug concentrations.20 Although a transient virologic response to HAART could result from the emergence of drug-resistant virus variants,21 22 it remains that, in this study, in vitro viral suppression was preserved in 2 of 4 transient responders (Table3). It is thus plausible that virologic failure in patients under HAART is driven by several factors such as plasma or tissue PI concentrations, sensitivity of evolving viral quasi-species to PIs, and the density and/or compartment of activated target cells. The observation that the effective-dose range of PIs to enhance cell survival was inversely correlated with the CD4 cell count, reflects an improved T-cell survival after normalization of CD4 compartment under HAART, thereby relatively reducing their sensitivity to cell survival enhancement by PIs. Our finding that the effective doses of PI to restore T-cell reactivity were at least 30-fold lower than that for suppressing viral replication, might also have an impact in clinical practice. Whether patients experiencing intolerable toxicity of PIs would benefit (in terms of T-cell recovery) from a reduced drug dose regimen deserves future studies.

In response to antigenic stimuli, antigen-presenting cells first activate resting lymphocytes, then lead to a cytokine-driven proliferation of responding cells near the activation sites, and finally restrain the population of responding cells by programmed cell death and by regenerating resting cell population with antigen-specific reactivity (referred as immune memory). Proliferative responses of peripheral blood T cells to in vitro recall antigen, alloantigen, and mitogen stimulation are lost progressively, along the course of HIV-1 infection23-25; these impaired proliferative responses are correlated with decreased peripheral blood CD4 cells and increased p24 antigenemia.26 Such decreased CD4 cells and increased p24 production (or viral replication) characterizes the pathogenic processes occurring in activated lymphoid organs of HIV-1–seropositive asymptomatic individuals.16,27,28 In this setting, compromised proliferative response of activated T cells in lymphoid organs is a permanent feature limiting the expansion of responding T cells. This “pause” status of activated T cells might intensify the density of productively infected CD4 cells and render activated T cells (both CD4 and CD8) more susceptible to activation-induced cell death (or apoptosis) through a “bystander” mechanism,29,30 thereby contributing to the progressive decline of peripheral blood T-cell (particularly CD4+compartment) pool and to the eventual development of AIDS. In this context, it is plausible that PIs enhance the expansion of responding T cells by restoring proliferative response, which results in the normalization of the resting T-cell population and contributes directly to the immune recovery documented in patients receiving HAART. Obviously, a sustained viral suppression by antiviral drugs will in turn favor the reconstitution of the resting T-cell population by decreasing antigenic stimuli. Taken together, our findings are in agreement with a recent long-term (30 months) follow-up study demonstrating that, although sustained virologic responders have a better clinical outcome than virologic nonresponders, the probability of clinical progression is low even in patients experiencing virologic failure.31

Recent studies have reported that susceptibility of peripheral blood T cells to apoptosis decreased in HIV-1–infected adults and children under HAART.32-34 Whether such a phenomenon reflects the direct down-regulation of T-cell apoptosis by HIV protease inhibitors or is merely the consequence of normalized resting T-cell compartment and function (such as increased proliferation to recall antigens, decreased plasma cytokines, declined serum β2-microglobulin and other soluble activation markers1-4,13) remains unclear. Although it has been recently found that apoptosis of in vitro mitogen-stimulated T cells upon Fas ligation can be down-regulated by ritonavir,32another HIV PI, we could not find any effect of indinavir or saquinavir on Fas-ligation–triggered apoptosis in both healthy donors' and HIV-1–infected patients' T cells. Meanwhile, apoptosis of donors' or patients' T cells upon TCR/CD3 ligation (which has been shown to be Fas independent34) is also unaffected by the drugs (Figure4). Moreover, a reduction in apoptosis observed after a 14-day culture of patients' T cells in the presence of the PIs (Table 4) is most likely the consequence of restored T-cell proliferation. Therefore, it seems unlikely that HIV PIs (at least, indinavir and saquinavir) exercise a direct activity on T-cell apoptosis. The decreased susceptibility of peripheral blood T cells to apoptosis observed in patients under HAART could be explained by the normalized resting T-cell reactivity and/or suppressed viral replication with PI-associated combination therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Arlie, L. Cao, S. Doré, H. Gozard, R. Salerno-Goncalves, L. Ty, J. Yuan, and Y. J. Zhao for technical assistance; M. Sala for measuring β2-microglobulin; W. Lowenstein and M. Stern for following part of the patients; M. Gozard and G. Nasso for secretarial assistance; Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Research Laboratories, and Roche Products for providing HIV protease inhibitors and reverse transcriptase inhibitors used in this study.

Supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche Sur le SIDA (ANRS), the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (SIDACTION), and the Association pour la Recherche, l'Etude et le Traitement des Maladies du Sang (AREMAS).

Reprints:Wei Lu, Laboratoire d'Oncologie et Virologie Moléculaires, Hôpital Laennec, 42 rue de Sèvres, 75007 Paris, France; e-mail: weilu@intercancer.net orcancero.laennec@lnc.ap-hop-paris.fr.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

![Fig. 4. Dose-dependent effects of indinavir or saquinavir on T-cell proliferation and apoptosis. / Results represent the mean ± SD of [3H]-thymidine uptake (A and B) and percentage apoptotic cells upon TCR/CD3 ligation with anti-CD3 antibodies (C and D) or upon Fas ligation with anti-Fas antibodies (E and F) in 10 healthy donor PBMCs (□) and 10 untreated HIV-1 patient PBMCs (▪).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/96/1/10.1182_blood.v96.1.250/4/m_bloo01328004x.jpeg?Expires=1768049869&Signature=KJDihWzR5vaZRQVRmM7cc3BfP6Q59jSUtJ5G8uICw5v14P4HFfVq9HKXTHe2rnsHofKqRRBoaE6g93o31GUHCIglqnSNGcifKQrH2EWZnI4iD33BJB36L1t5QuX210F9PeBSUGIzC4M1D4JAp3eavDGGTNZAD1~B~BmylrdN2hUe1Sjw6aX79AUGJ~-oMg1qII~~vBuEfodwod6oZmChaLvBbmcX3y63n7SqtajLlrlP2rOc1m9ptsjCftM4RzcO4LUUyHNBQcLc8YagnhuT1GooS6MBy2Lpo4YpCioBXCWWwjbaI847ileWMJTewT19qTeXwtBUUJz9y6STOScCcw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)