Abstract

After the transplantation of unmodified marrow from human leukocyte antigen-matched unrelated donors receiving cyclosporine (CSP) and methotrexate (MTX), the incidence of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is greater than 75%. Tacrolimus is a macrolide compound that, in previous preclinical and clinical studies, was effective in combination with MTX for the prevention of acute GVHD. Between March 1995 and September 1996, 180 patients were randomized in a phase 3, open-label, multicenter study to determine whether tacrolimus combined with a short course of MTX (n = 90), more than CSP and a short course of MTX (n = 90), would reduce the incidence of acute GVHD after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors. There was a significant trend toward decreased severity of acute GVHD across all grades (P = .005). Based on the Kaplan-Meier estimate, the probability of grade II-IV acute GVHD in the tacrolimus group (56%) was significantly lower than in the CSP group (74%;P = .0002). Use of glucocorticoids for the management of GVHD was significantly lower with tacrolimus than with CSP (65% vs 81%, respectively; P = .019). The number of patients requiring dialysis in the first 100 days was similar (tacrolimus, 9; CSP, 8). Overall and relapse-free survival rates for the tacrolimus and CSP arms at 2 years was 54% versus 50% (P = .46) and 47% versus 42% (P = .58), respectively. The combination of tacrolimus and MTX after unrelated donor marrow transplantation significantly decreased the risk for acute GVHD than did the combination of CSP and MTX, with no significant increase in toxicity, infections, or leukemia relapse.

Introduction

The risks for acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) are significantly increased after marrow transplantation from matched unrelated donors than from family member donors using pharmacologic prophylaxis regimens, most commonly the combination of cyclosporine (CSP) and methotrexate (MTX).1-10 This may result from disparities in major histocompatibility loci unrecognized by current typing methodologies or from a greater degree of disparity in minor histocompatibility loci.2,3,8 The incidence of acute grade II-IV and grade III-IV GVHD after transplantation from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched unrelated donors has been reported as 77% and 35%, respectively, with this regimen.3 New regimens or agents are required that provide more effective GVHD prophylaxis but do not increase infections or toxicity.

The macrolide tacrolimus (FK506) inhibits T-cell activation by forming a complex with FK binding protein-12, which blocks the serine-threonine phosphatase activity of calcineurin.11-15 Tacrolimus is more effective than CSP for both the treatment and the prevention of liver and kidney allograft rejection.16-18 In preclinical studies, tacrolimus prevented GVHD after marrow transplantation in rats and dogs.19,20 In the dog model, tacrolimus in combination with MTX was significantly more effective than tacrolimus alone.20 Phase 2 clinical studies established that tacrolimus was well tolerated and effective for GVHD prophylaxis.21-24 In a phase 3 study of GVHD prophylaxis after marrow transplantation from matched sibling donors, there was a reduced incidence of acute GVHD in a treatment group receiving tacrolimus and MTX than in the control group, which received CSP and MTX.25 Based on these results, a phase 3 study of GVHD prevention was conducted to compare tacrolimus and MTX with CSP and MTX after marrow transplantation from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched unrelated donors.

Patients and methods

Patients

Between March 1995 and September 1996, 180 patients were enrolled in the study at 10 institutions in the United States. Data collection was completed and analyzed at 6 months and at 2 years after transplantation, or at death, for all patients. Between 6 months and 2 years, data collection was limited to the status of chronic GVHD, relapse, and survival. Patients 12 years of age or older were eligible to participate in the study if they were scheduled to receive a bone marrow transplant from an unrelated donor for chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic or accelerated phase, early acute leukemia or malignant lymphoma (first or second remission or in untreated first relapse), aplastic anemia (AA), or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Patients were excluded from the study if the estimated creatinine clearance was less than 60 mL/minute, Karnofsky score was lower than 60%, or serology was positive for human immunodeficiency virus, or if they had uncontrolled infections or had previously undergone hematopoietic stem cell or solid organ transplantation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each center and was explained to each patient in detail, and each patient provided written, informed consent.

Study design

The study was a randomized, open-label, multicenter phase 3 study of the combination of tacrolimus and MTX compared with the combination of CSP and MTX for the prevention of acute GVHD after marrow transplantation from matched unrelated donors. Prerandomization stratification within each center was based on the degree of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR match between the patient and the donor. Patients were stratified according to whether the donor was a complete 6-antigen HLA match or a 1-antigen HLA serologic mismatch in class 1 or a molecular mismatch at DRB1. The sample size was selected to ensure, with a probability of 80%, that the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference in acute GVHD did not exceed 10%.26 The sample size calculation was based on the historical incidence of 75% GVHD in the MTX/CSP control arm.3,7,8 27-29

HLA typing and donor matching

Donor selection was based on typing for HLA-A and HLA-B antigens by serologic methods, including all splits defined by the World Health Organization Nomenclature Committee at the 10th Histocompatibility Workshop in November 1987.30,31 Typing for HLA-DRB1 alleles was by DNA hybridization, with sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes.30-32 One minor or major antigen mismatch at the HLA-A, HLA-B, or HLA-DRB1 locus, as defined by the National Marrow Donor Program, was allowed. At the HLA-A or HLA-B locus, a minor mismatch was defined as different antigens in the same cross-reactive group and a major mismatch as different antigens outside the same cross-reactive group. At the HLA-DRB1 locus, a minor mismatch was defined, by polymerase chain reaction/SSOP typing, as antigens with an identical serologic DR type but different DRB1 alleles. A major DRB1 mismatch was defined as antigens with a different serologic DRB1-18 type.

Transplantation procedure and supportive care

Preparative regimens were assigned according to the treatment protocols at the investigational sites. All patients underwent a preparative regimen that included either total body irradiation or busulfan. Unmodified donor marrow was infused on day 0. Intravenous immunoglobulin was administered either routinely, at a minimum of 100 mg/kg every week until day 100, or to ensure that serum IgG levels were greater than 400 mg/dL. All patients received either prophylactic or preemptive cytomegalovirus therapy and antifungal prophylaxis according to institutional protocols.

Intravenous and oral doses of tacrolimus and CSP were calculated using lean body weight. All patients were given tacrolimus or CSP on the day before transplantation and were scheduled to continue immunosuppression with these drugs as randomized for 6 months after transplantation. Tacrolimus was started at a dose of 0.03 mg/kg and CSP at 3 mg/kg, and both were administered as 24-hour continuous IV infusion. Patients were converted from the IV to the oral formulation of tacrolimus and CSP when it could be tolerated at a ratio of 1:4 in 2 divided doses per day based on the last IV dose. Measurements of whole blood tacrolimus were by IMx assay, and CSP levels were by monoclonal or polyclonal antibody assay or high-pressure liquid chromatography, respectively.33 34 During the first 8 weeks, tacrolimus blood concentrations were maintained between 10 and 30 ng/mL as a steady state during continuous IV infusion or as trough levels during oral treatment, and CSP levels were maintained between 150 and 450 ng/mL, except in those centers using a polyclonal antibody assay; then the levels were maintained between 300 and 900 ng/mL. Dose reductions of tacrolimus and CSP were recommended for increases in serum creatinine of more than 1.5 times baseline or other serious toxicities associated with these agents. In some patients with transplantation-related complications in whom tacrolimus or CSP doses were reduced, corticosteroids were administered as substitute prophylaxis for acute GVHD. In the absence of GVHD, tacrolimus and CSP administration were tapered beginning at week 9. Tacrolimus and CSP were continued beyond 6 months in patients with chronic GVHD. The MTX doses were 15 mg/m2 on day 1 and 10 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11 after marrow transplantation.

Engraftment

Engraftment was defined as occurring on the first of 3 successive days after marrow transplantation, with neutrophil counts 0.5 × 109/L or higher. Platelet recovery was considered to have occurred if there was no requirement for platelet transfusion for a period of at least 30 days. Graft failure was defined as failure to maintain an absolute neutrophil count 0.5 × 109/L or higher for at least 3 consecutive determinations, beginning 30 days after transplantation.

Adverse events

To assess nephrotoxicity, patients were evaluated for a doubling of the baseline serum creatinine concentration or a serum creatinine concentration greater than 2 mg/dL. Severe veno-occlusive disease (VOD) was assessed as previously defined.35 A comparison of treatment required for hypertension and hyperglycemia was performed. Adverse events were assessed and recorded after marrow transplantation for an evaluation of safety. Primary causes of death were categorized according to the National Marrow Donor Program criteria by one of the investigators (R.A.N.).

Assessment and treatment of GVHD

An overall grade of acute GVHD was assigned by the site investigator at each institution according to the clinical assessment using modified Seattle criteria.36,37 Biopsies were obtained when indicated to corroborate the clinical diagnosis of GVHD. In addition, an Endpoint Evaluation Committee (EPEC) was formed to assess independently the acute GVHD end point on all patients participating in the study. The committee was composed of 3 expert clinicians whose institutional sites were not participants in the clinical trial. Committee members retrospectively reviewed abstracts and flow sheets of the clinical data and pertinent supportive documentation, but they were blinded to the study drug assignment and GVHD treatment. Biopsies were available for review if subsequent evaluation of pathologic conditions was necessary to aid in the clinical evaluation. A determination of the stage and grade of acute GVHD was made.37 Committee members assessed the clinical data independently of each other, and agreement was necessary among 2 of the 3 committee members for the overall grade of acute GVHD. For the site investigator and the EPEC assessment, patients were censored for acute GVHD evaluation at the time of recurrent malignancy, second transplantation, or death. Treatment of grade II-IV acute or of chronic GVHD was determined by the investigational site. Patients were continued on the randomized drug assignment as the primary immunosuppressive therapy. A patient was evaluable for chronic GVHD if engraftment occurred and the patient survived without relapse for 75 days after transplantation. Assessments were made according to previously described criteria.38

Statistical analysis

The primary efficacy outcome for this study was the occurrence of grade II to IV acute GVHD within 100 days of transplantation. Secondary efficacy outcomes included severe (grade II-IV) acute GVHD, chronic GVHD, death, or relapse. All analyses were performed on an intent-to-treat basis. The 95% CI for treatment differences were calculated based on Kaplan-Meier estimates using the variance derived from Greenwood's formula.39 Kaplan-Meier estimates for GVHD were censored for death, relapse, or second transplant surgery. Relapse-free survival rates were calculated using death and relapse as events. Statistical comparisons between treatment groups were performed using the Wilcoxon test for Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the χ2 test for proportions. All P values were 2 sided, and a value of greater than .05 was considered statistically significant. All grades of acute GVHD were tested in an ordinal regression model to evaluate a trend in overall severity.

Results

Patient and transplant characteristics

One hundred eighty patients were enrolled in the study, 90 each in the tacrolimus and the CSP groups. Demographics and transplant characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table1. There was an imbalance of the HLA class II antigen mismatches with 11 in the CSP group and 4 in the tacrolimus group (P = .06). Otherwise, pretransplant characteristics were similar for both treatment groups. In 167 patients for whom the data were available, there was no difference in the median marrow cell dose between the 2 treatment groups (P = .76). The median ages were 34 years (range, 13-61 years) and 35 years (range, 12-54 years) for the tacrolimus and CSP groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in the number of doses of MTX received by patients (Table 2).

Engraftment

Engraftment took place in 82 patients (91%) in the tacrolimus group and 77 patients (86%) in the CSP group (Table3). The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 21 days (range, 12-41 days) for patients in the tacrolimus group and 20 days (range, 11-34 days) for patients in the CSP group. By 6 months after transplantation, platelet transfusion independence occurred in 50 patients (56%) in the tacrolimus group and 42 patients (47%) in the CSP group.

Acute GVHD

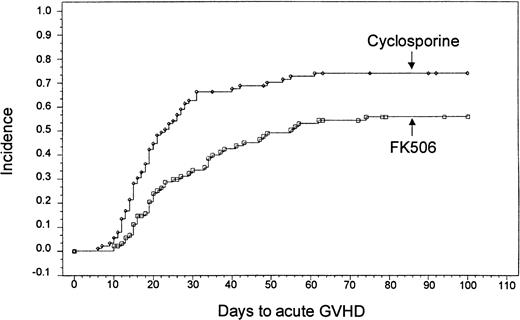

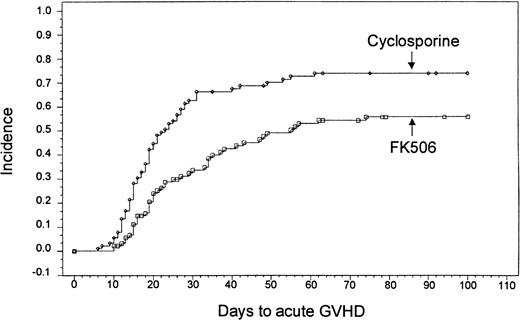

Based on Kaplan-Meier estimates, the incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD, as assessed by the investigator at the study site, was 56% (n = 46) in the tacrolimus-treated group and 74% (n = 63) in the CSP-treated group (P = .0002) (Figure1). The distribution of GVHD grades in both groups is presented in Table 4. A test for trend of the distribution of all grades of acute GVHD revealed an overall decrease in severity (P = .005). There was no treatment by center interaction for the overall incidence of acute GVHD (P = .802, Breslow-Day test). There was also no difference in the incidence of acute GVHD among subgroups of patients classified by age, use of total body irradiation, or HLA match. A stratified analysis confirmed that even with the imbalanced randomization of the HLA class II mismatches, the decreased incidence of acute GVHD in the tacrolimus group remained highly significant (P = .0066) (Table 5).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of acute GVHD based on site investigator assessment (tacrolimus, 56%; CSP, 74%;P = .0002).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of acute GVHD based on site investigator assessment (tacrolimus, 56%; CSP, 74%;P = .0002).

In a separate analysis by the EPEC it was confirmed that there was a lower incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD in the tacrolimus group than in the CSP group (20% vs 32%, respectively; P = .038). All patients identified with acute GVHD by the EPEC had also been determined to have acute GVHD by the site investigator assessment. Of those patients identified with grade II-IV acute GVHD by the EPEC assessment, 69% and 88% of patients in the tacrolimus group and 69% and 96% of patients in the CSP group had grade III or IV GVHD by the site investigator assessments and 2 or 3 system GVHD, respectively. Distributions of organ involvement were similar between the tacrolimus and the CSP groups. All patients with grade II-IV acute GVHD had first-line treatment with systemic corticosteroids, but one patient in the CSP group was treated with antithymocyte globulin. The number of patients who received corticosteroids for substitute prophylaxis or for primary treatment of acute GVHD after marrow transplantation was significantly less in the tacrolimus group (66%) than in the CSP group (81%) (P = .018). The cumulative dose of corticosteroids required by patients at day 105 was significantly lower in the tacrolimus group (P = .016).

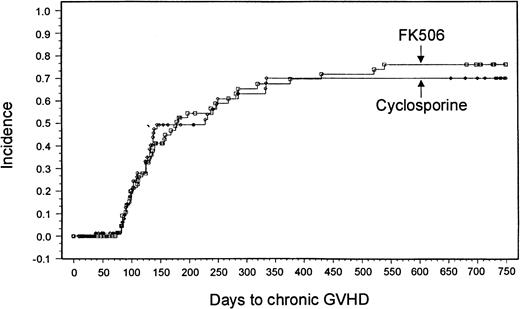

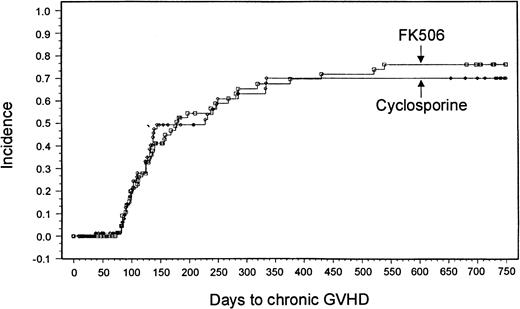

Chronic GVHD

Sixty-nine patients in the tacrolimus group and 63 patients in the CSP group were evaluable for chronic GVHD. A minimum 2-year follow-up after transplantation revealed no significant differences in the overall incidence based on Kaplan-Meier estimates or severity of chronic GVHD between the 2 treatment groups (tacrolimus, 43 patients [76%]; CSP, 38 patients [70%]; P = .8791) (Figure2). Ten patients in the tacrolimus group and 3 in the CSP group had de novo onset of chronic GVHD.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of chronic GVHD (tacrolimus, 76%; CSP, 70%; P = .88).

Adverse events

Nephrotoxicity was one of the most common adverse events observed in both groups within 100 days of transplantation. The incidence of serum creatinine greater than 2 mg/dL was greater in the tacrolimus group (P = .037), but there was no difference in the incidence of doubling serum creatinine over baseline (P = .356) or of severe nephrotoxicity requiring dialysis (P = .799) (Table 6). Mean peak serum creatinine levels were 2.6 (± 1.7 SD) mg/dL and 2.2 (± 1.2 SD) mg/dL in the tacrolimus and the CSP groups, respectively. Mean serum creatinine level at 6 months after transplantation was 1.2 mg/dL in each group. Median peak serum bilirubin concentrations during the first 28 days were 2.2 (range, 0.5-48.6) mg/dL and 2.8 (range, 0.7-54.0) mg/dL for the tacrolimus and the CSP groups, respectively (Table 6). There was no difference in the incidence of VOD, nor was there a difference between the tacrolimus and CSP groups in the incidence of hypertension (21% vs 32%) or hyperglycemia requiring treatment at day 100 (12% vs 14%, respectively). Neurologic side effects were also similar in both arms of the study. Ten patients in each group had convulsions. There was no significant difference in the incidence of hypokalemia or hypomagnesemia. One patient in each group had hemolytic–uremic syndrome/thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Seventy-eight patients in the tacrolimus group and 86 patients in the CSP group had at least one documented infection within 6 months of transplantation (Table 7).

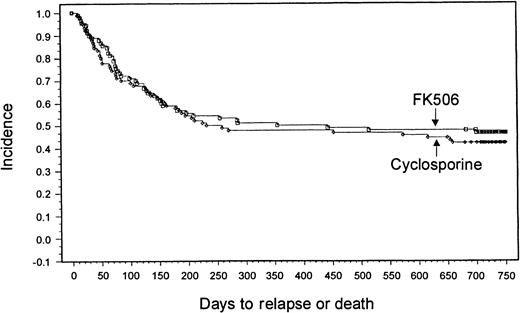

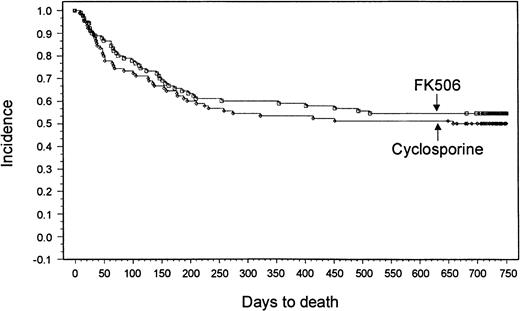

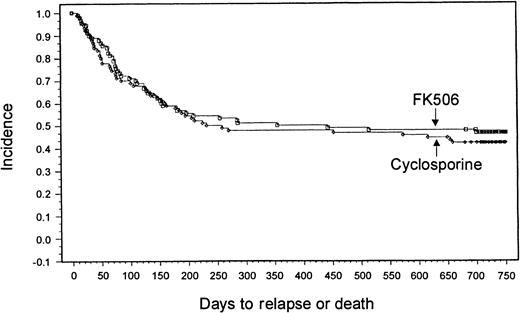

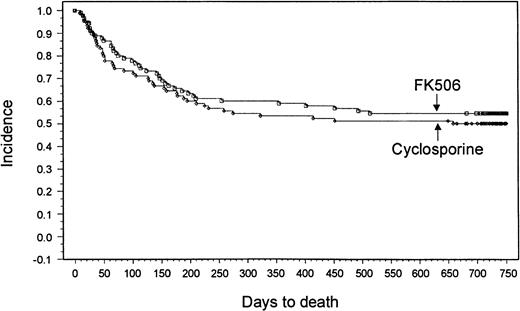

Survival and relapse

With a minimum follow-up of 2 years, it was seen that 18 patients (20%) had relapses in the tacrolimus group and 14 patients (15.6%) had relapses in the CSP group. Median times to relapse were 127 days (range, 53-700 days) and 162 days (range, 75-655 days) from transplantation for the tacrolimus and CSP groups, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of relapse-free survival at 2 years after transplantation was 47% in the tacrolimus group and 42% in the CSP group (P = .57) (Figure 3). Overall survival rates at 2 years were 54% in the tacrolimus group and 50% in the CSP group (P = .464) (Figure4). The imbalance of HLA class II mismatches did not influence overall survival in a stratified analysis (P = .50). Causes of death were similar between the 2 groups (Table 8). Nonrelapse mortality rates were 33% and 42% in the tacrolimus and CSP groups, respectively (P = .24).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of relapse-free survival (tacrolimus, 47%; CSP, 42%; P = .58).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of relapse-free survival (tacrolimus, 47%; CSP, 42%; P = .58).

Kaplan-Meier estimate of survival (tacrolimus, 54%; CSP, 50%; P = .46).

Discussion

Transplantation from HLA-matched unrelated donors results in a high incidence of acute GVHD.1,3-9 The most commonly used pharmacologic regimen for GVHD prophylaxis is the combination of CSP and MTX, which was used for the control arm of this study.2,10 Strategies for ex vivo T-cell depletion are also under investigation, but no large studies have demonstrated an improved outcome.27,40,41 A decrease in the incidence of acute GVHD in this high-risk group could improve results by reducing patient morbidity, simplifying medical management, and reducing transplantation-related deaths. However, because of the beneficial effects of a graft-versus-host reaction that contributes to the promotion of engraftment and the maintenance of remission, measures for the depletion or inhibition of T-cell activity have not improved or have worsened overall outcome in some studies.42 43 In this study, tacrolimus and MTX reduced the incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD without compromising other outcomes, including relapse, based on a follow-up of 2 years in all patients. A reduction in the use of high-dose corticosteroids, which was observed in the tacrolimus arm, may improve management of patients after transplantation by decreasing the risk for other complications, including behavioral and mood changes, myopathy, osteoporosis, and avascular necrosis.

Although acute GVHD was less prevalent in patients receiving tacrolimus, the incidence of chronic GVHD at 2 years after transplantation was similar in both groups. Previous studies of pharmacologic immunosuppression to decrease the incidence of acute GVHD showed that it did not substantially reduce the incidence of chronic GVHD.2,25,44-46 This might have occurred because patients without acute GVHD started the taper of immunosuppressive agents at week 8 after transplantation.47,48 The mean time to onset of chronic GVHD has been reported as 201 days after transplantation, so it is expected that the 2-year follow-up in the current study was sufficient to evaluate the development of this late complication.49

Nephrotoxicity was the most common toxicity related to tacrolimus. The incidence of nephrotoxicity has been greater with tacrolimus-based regimens than CSP-based regimens in previous phase 3 studies of marrow or solid organ transplantation.16,17,25 In the current study, the number of patients with nephrotoxicity was similar in both arms, but there was an increased incidence of peak serum creatinine levels greater than 2 mg/dL in the tacrolimus group. Nephrotoxicity was usually reversible by adjustment of the drug dose. The frequency of severe nephrotoxicity requiring dialysis was similar in both groups. The increased frequency of nephrotoxicity found in previous studies might have resulted from the higher doses of tacrolimus or the higher target ranges for whole blood concentration used in those studies.16,25,34 An analysis from the phase 3 HLA-matched sibling study observed an association between whole blood tacrolimus levels greater than 20 ng/mL and an increased incidence of nephrotoxicity without prevention of acute GVHD.50 51Based on these data, the risk for nephrotoxicity may be reduced without compromising the prevention of acute GVHD by targeting blood levels between 10 and 20 ng/mL. No other differences in adverse effects were noted between the 2 arms of the study. In this study, an effective dosing strategy for tacrolimus was identified in which GVHD prevention was improved but adverse effects were not increased.

To some degree, the grading of GVHD is subjective, and this results in variability of grading among investigators. Patients with advanced hematologic malignancy have an increased incidence of transplantation-related complications that confounds the staging of organ systems for acute GVHD.25,52 In addition, patients with advanced hematologic malignancies are a more heterogeneous group, which leads to difficulties in stratification that may affect other end points.25 53 To avoid some of the difficulties associated with the grading of acute GVHD, patients with advanced hematologic malignancies were excluded from the study. To assess more accurately the outcomes of new regimens for GVHD prevention, future phase 3 studies should exclude patients with advanced hematologic malignancies unless other questions specific to this population are being addressed.

Many previous informative phase 3 studies of GVHD prevention have had an open-label design; however, this is a situation in which expectation bias can influence the results.54 Therefore, a blinded committee (EPEC) of 3 experts in the field independently conducted retrospective grading of acute GVHD. This format of retrospectively grading acute GVHD has been described as effective, with sufficient correlation between 2 of 3 reviewers to allow consensus on any single patient.52 54 Although not completely effective for the identification of all cases of less severe or single-system acute GVHD, results of the EPEC evaluation confirmed that the group of patients who received tacrolimus was clearly determined to have a decreased incidence of acute GVHD. If placebo-controlled, double-blinded studies for GVHD prevention are not feasible, an EPEC should be established to confirm clinical outcomes and to avert expectation bias.

Patients with grade II and grade II-IV acute GVHD experience approximately 0% to 15% and 20% to 50% more transplantation-related deaths, respectively, than patients with grade 0-I acute GVHD.55-57 The number of deaths from GVHD was lower in the tacrolimus group, and there was a significant reduction in the severity of acute GVHD, but the magnitude of these differences did not have a significant effect on overall survival rates. There are many competing causes of death after allogeneic marrow transplantation, including regimen-related toxicity, infection, and relapse. The design of future GVHD prevention studies in recipients of stem cell grafts from unrelated donors will have to account for these smaller differences between control and treatment arms if the impact of new regimens on survival is to be fully assessed.

The combination of tacrolimus and MTX was more effective than CSP and MTX for the prevention of acute GVHD, and it reduced the need for corticosteroid treatment after marrow transplantation without an increase in graft failure, relapse, or toxicity. The use of tacrolimus and MTX for GVHD prevention should improve the quality of life for patients and simplify the medical management of patients after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rochelle Maher and Jay Erdman from Fujisawa Healthcare, Inc, and Paul Martin, John Hansen, and Barry Storer of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center for their assistance with or review of the manuscript. We also thank the members of the Endpoint Evaluation Committee, especially Mary Horowitz, Georgia Vogelsang, and Nelson Chao.

Supported in part by a grant from Fujisawa Healthcare, by National Institutes of Health grant CA18029 (R.A.N., C.A., R.S.), and by the Jock Adams Fund (J.H.A.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Richard A. Nash, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue N, D1-100, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA 98109-1024; e-mail: rnash@fhcrc.org.