Abstract

Erythropoietin (EPO) allows erythroid precursors to proliferate while protecting them from apoptosis. Treatment of the EPO-dependent HCD57 murine cell line with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate, a tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor, resulted in both increased tyrosine protein phosphorylation and prevention of apoptosis in the absence of EPO without promoting proliferation. Orthovanadate also delayed apoptosis in primary human erythroid progenitors. Thus, we investigated what survival signals were activated by orthovanadate treatment. Expression of Bcl-XL and BAD phosphorylation are critical for the survival of erythroid cells, and orthovanadate in the absence of EPO both maintained expression levels of antiapoptotic Bcl-XLand induced BAD phosphorylation at serine 112. Orthovanadate activated JAK2, STAT1, STAT5, the phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3 kinase) pathway, and other signals such as JNK and p38 without activating the EPO receptor, JAK1, Tyk2, Vav, STAT3, and SHC. Neither JNK nor p38 appeared to have a central role in either apoptosis or survival induced by orthovanadate. Treatment with cells with LY294002, an inhibitor of PI-3 kinase activity, triggered apoptosis in orthovanadate-treated cells, suggesting a critical role of PI-3 kinase in orthovanadate-stimulated survival. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) was poorly activated by orthovanadate, and inhibition of MAPK with PD98059 blocked proliferation without inducing apoptosis. Thus, orthovanadate likely acts to greatly increase JAK/STAT and PI-3 kinase basal activity in untreated cells by blocking tyrosine protein phosphatase activity. Activated JAK2/STAT5 then likely acts upstream of Bcl-XL expression and PI-3 kinase likely promotes BAD phosphorylation to protect from apoptosis. In contrast, MAPK/ERK activity correlates with only EPO-dependent proliferation but is not required for survival of HCD57 cells.

Introduction

Erythropoietin (EPO) is a glycoprotein hormone that allows erythroid precursors to proliferate and mature, while providing protection from apoptosis.1-4 EPO binds to cell surface receptors (EPOR)5 activating a number of transduction molecules, including JAK2,6-9 STAT5,6,10STAT1,10 SHC,11 SHIP,12ERK,13 JNK,14 p38,15phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI-3 kinase),16 and protein kinase B, also known as Akt (PKB/Akt).17 To better understand the complex and intricate signal transduction pathways responsible for the different effects of EPO, we have investigated the hypothesis that the signals that promote proliferation can be separated from the signals that promote protection from apoptosis. We hypothesize that certain molecules may play a role in the protection from apoptosis, whereas others are involved in proliferation. As our model, we have employed the erythroleukemic, EPO-dependent, murine cell line HCD57.18 19 This cell line proliferates in response to EPO. In the absence of EPO, apoptosis occurs.

Curiosity about the effects of a tyrosine protein phosphatase inhibitor, such as orthovanadate, in EPO signal transduction is natural because EPO signaling is controlled by both the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of many transduction molecules.1-4 In the early 1900s, vanadium complexes had a medicinal use in the treatment of anemia.20 The Spivak laboratory reported that a low concentration of orthovanadate (5 μmol/L) acted synergistically with suboptimal EPO concentrations to stimulate DNA synthesis in HCD57 cells.21 Lack of an effect of orthovanadate on tyrosine phosphorylation in erythroid progenitors isolated from patients with polycythemia vera suggested that a tyrosine protein phosphatase deficiency in the diseased cells resulted in increased sensitivity to growth factors.22 We found that 70 μmol/L orthovanadate protected HCD57 cells from apoptosis after EPO withdrawal for at least 96 hours. Cells cultured in these conditions showed no more proliferation than HCD57 cells cultured without EPO. Thus, orthovanadate-treated cells provide a unique system in which sufficient signaling existed after tyrosine phosphatase inhibition to prevent apoptosis but not to stimulate proliferation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and immunoprecipitation

HCD57 cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Life Technologies, Inc, Gaithersburg, MD), 25% fetal calf serum, 10 μg/mL gentamicin, 1 unit EPO/mL at 37°C in a 5% CO2 environment. For each immunoprecipitation sample, 1 × 107 HCD57 cells were washed 3 times in serum-free media and cultured for 24 hours in the absence of EPO with various concentrations of orthovanadate (0, 10, or 70 μmol/L). The cells were then either treated for 5 minutes with 10 units EPO/mL at 37°C or mock treated. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation as described previously10 with anti-EPOR (raised against a 15 amino acid peptide corresponding to the C-terminal of the murine receptor),19 anti–Bcl-XL (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-JAK1 (UBI), anti-JAK2 (UBI), anti-Tyk2 (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY), anti–ERK-1 (Santa Cruz), anti-SHC (Transduction Laboratories), or anti–JNK-1 (Santa Cruz) antibodies. Western blot analysis was conducted using antiphosphotyrosine (UBI), anti-PKB/Akt (New England Biolabs [NEB], Beverly, MA), anti-phosphoPKB/Akt (NEB), anti-phosphoJNK (NEB), anti-p38 (NEB), anti–phospho-p38 (NEB), anti–Bcl-XL (Transduction Laboratories), anti-STAT5A (Santa Cruz), anti-STAT5B (Santa Cruz), or the antibodies listed above. Western blotted proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Ascateway, NJ). For the cell viability studies, cells were washed as described above and cultured with EPO, without EPO, or without EPO but supplemented with 10 to 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. Cell viability was determined by counting cells on a hemocytometer in the presence of 0.2% trypan blue. Human erythroid progenitors were purified as previously described.27 Purity of the cell prep was 90% or greater, based on flow cytometry analysis for glycophorin A positive and CD71 positive populations.

STAT DNA binding studies

Nuclear extracts were prepared as described previously.10 The 10 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with a γ-32P]ATP–labeled DNA fragment corresponding to either the STAT5 binding site in the rat β-casein promoter, the prolactin-inducible element (PIE),28 or the STAT1/STAT3 binding site, the sis-inducible element (SIE),26 and subjected to electrophoresis as described previously.29 30 Supershifts were performed using anti-STAT1 (Transduction Laboratories), anti-STAT3 (Transduction Laboratories), anti-STAT5A (Zymed Laboratories, Inc, San Francisco, CA), and anti-STAT5B (Zymed) antibodies.

In vitro kinase assay

Anti–ERK-1 or anti–JNK-1 immunoprecipitated proteins were concentrated into 75 μL of lysis buffer and subjected to an in vitro kinase assay.31 Myelin basic protein (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) was used as a substrate to measure ERK-1 activity, whereas GST-jun (a generous gift from Paul Dent) was used to measure JNK-1 activity. Briefly, 10 μL of immunoprecipitate was incubated in 20 mmol/L β-glycerophosphate, 0.1 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate, 1 mmol/L NaF, 20 mmol/L KHEPES, pH 7.4, 15 mmol/L magnesium acetate, 1 mmol/L KEGTA, 1 mmol/L dithiothretiol, 1 μg/mL each of chymotrypsin, leupeptin, aprotinin, pepstatin, and soybean trypsin inhibitor, 0.5 μmol/L PKI protein kinase inhibitor peptide (TTYADFIASGRTGRRNAIHD), 0.5 mg/mL of substrate, 50 μmol/L ATP, and 0.18 MBq (5 μCi) of γ-32P]ATP for 15 minutes at 30°C. The substrate was then subjected to polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel was fixed, dried in vacuo, and visualized by exposure to x-ray film.

Apoptosis studies

Cells were cultured for 96 hours with EPO, without EPO, or without EPO but supplemented with 10, 30, 50, or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. To analyze DNA laddering (fragmentation), cells were harvested and genomic DNA was isolated using the Puregene Kit (PGC Scientifics, Frederick, MD). The 10 μg of genomic DNA was resolved on 2.25% agarose, 1X TAE (40 mmol/L Tris Acetate, pH 8.0, 1 mmol/L EDTA), 300 ng EtBr/mL of gel. DNA laddering indicative of apoptosis was visualized with ultraviolet light. Annexin V–FITC staining was performed using the ApoAlert Annexin V Apoptosis Kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and evaluated by FACS (Becton Dickinson, Rutherford, NY).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells cultured in the desired conditions were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed overnight in a solution of 25% PBS, 25% fetal calf serum, and 50% ethanol. The cells were washed and incubated 1 hour in propidium iodide (PI) staining solution (PBS, 0.05 mg/mL RNase A, 0.1 μmol/L EDTA, and 0.05 mg/mL PI) and analyzed by FACS (Becton Dickinson).

Results

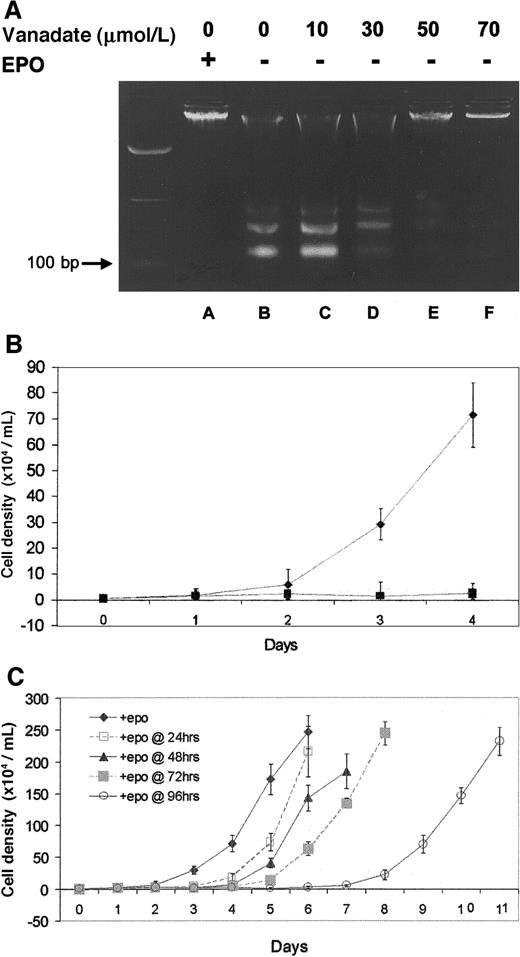

Orthovanadate protected EPO-dependent cells from apoptosis

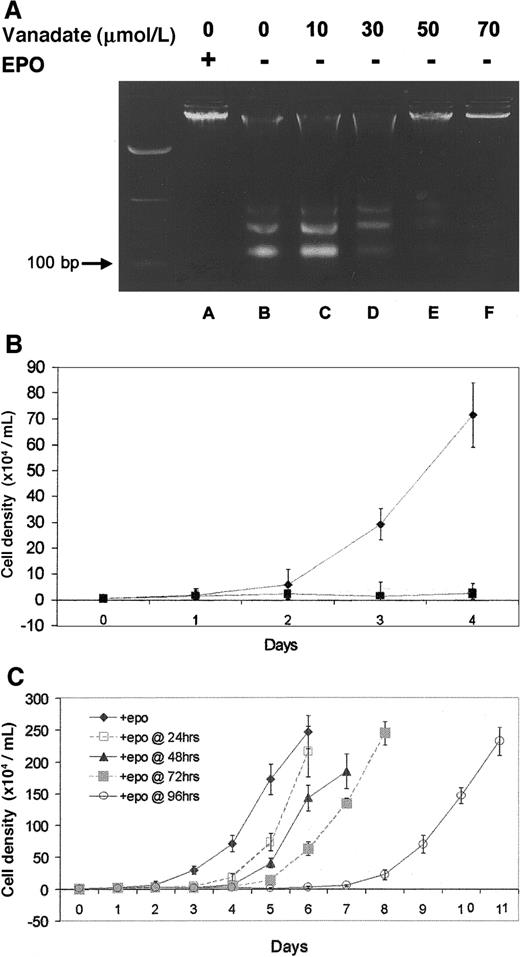

Protection from genomic DNA laddering (fragmentation) was used to determine the ability of orthovanadate to prevent apoptosis in HCD57 cells deprived of EPO. First, HCD57 cells were cultured either with EPO or without EPO but with the 10 to 70 μmol/L concentrations of orthovanadate for 96 hours. Genomic DNA was isolated and analyzed for laddering by electrophoresis on an agarose gel (Figure1A). In cells cultured in the presence of EPO (lane A), genomic DNA was intact, whereas in cells deprived of EPO (lane B), DNA laddering characteristic of apoptosis was evident and intact DNA was virtually absent. The 10 (lane C) and 30 μmol/L (lane D) orthovanadate afforded no protection from apoptosis, 50 μmol/L (lane E) provided moderate protection, and 70 μmol/L (lane F) provided significant protection. Annexin V–FITC staining of apoptotic cells confirmed these findings (data not shown).

Effect of orthovanadate on HCD57 viability and proliferation.

(A) HCD57 cells were cultured for 96 hours in the presence of EPO (lane A), in the absence of EPO (lane B) or in the absence of EPO and supplemented with different concentrations of orthovanadate (lanes C-F) as indicated. For each growth condition, 10 μg of genomic DNA were analyzed by agarose gel. (B) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (♦), in the absence of EPO (○), or in the absence of EPO and supplemented with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate over a period of 96 hours (▪). The number of viable cells was determined each day by trypan blue exclusion. Error bars indicate the standard error of 8 determinations. (C) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (♦) or in the absence of EPO but supplemented with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. At 24 (□), 48 (▴), 72 (░) and 96 (○) hours, aliquots of cells were removed from the minus EPO/plus orthovanadate culture. Each culture was washed free of orthovanadate and placed in fresh EPO containing media. The number of viable cells was determined each day by trypan blue exclusion. Error bars indicate the standard error of 8 determinations.

Effect of orthovanadate on HCD57 viability and proliferation.

(A) HCD57 cells were cultured for 96 hours in the presence of EPO (lane A), in the absence of EPO (lane B) or in the absence of EPO and supplemented with different concentrations of orthovanadate (lanes C-F) as indicated. For each growth condition, 10 μg of genomic DNA were analyzed by agarose gel. (B) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (♦), in the absence of EPO (○), or in the absence of EPO and supplemented with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate over a period of 96 hours (▪). The number of viable cells was determined each day by trypan blue exclusion. Error bars indicate the standard error of 8 determinations. (C) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (♦) or in the absence of EPO but supplemented with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. At 24 (□), 48 (▴), 72 (░) and 96 (○) hours, aliquots of cells were removed from the minus EPO/plus orthovanadate culture. Each culture was washed free of orthovanadate and placed in fresh EPO containing media. The number of viable cells was determined each day by trypan blue exclusion. Error bars indicate the standard error of 8 determinations.

Orthovanadate also delayed apoptosis in EPO-dependent human erythroid progenitor cells in the absence of EPO (Table1). Purified human erythroid progenitors (90% or more pure as determined by flow cytometry for the markers glycophorin A and CD71) were removed from growth factors (EPO, stem cell factor [SCF], and insulin-like growth factor 1) on day 6. The cells were then cultured either with growth factors or without growth factors but with the selected concentrations of orthovanadate for 20 hours. The cells were analyzed for evidence of apoptosis with Annexin V–FITC and PI (Table 1). In the presence of growth factors, very little apoptosis (5.3%) was observed. Without growth factors, a majority of the cells (70%) were apoptotic within 20 hours. The 20 μmol/L orthovanadate only marginally reduced the number of apoptotic cells detected (48.7% apoptotic), whereas treatment with 50 or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate greatly reduced the number of apoptotic cells (a 57.3% and 57.1% reduction, respectively) such that less than 30% of the cells showed any signs of apoptosis.

The 70 μmol/L orthovanadate promoted neither proliferation nor differentiation

Proliferation studies revealed different growth curves for HCD57 cells in the various culture conditions investigated. In the presence of EPO (Figure 1B), HCD57 cells showed a vigorous proliferation. After EPO was withdrawn, proliferation was absent (Figure 1B). Interestingly, the addition of 70 μmol/L orthovanadate did not promote proliferation (Figure 1B). In fact, cells cultured with orthovanadate in the absence of EPO showed no more proliferation than cells cultured without orthovanadate in the absence of EPO. Cell cycle analysis with PI staining showed that 70 μmol/L orthovanadate treatment for 24 hours in the absence of EPO caused no significant change in the cell cycle profile compared with cells cultured in EPO (data not shown). Thus, orthovanadate-treated cells stopped proliferation in all phases of the cell cycle. This condition of low-to-no proliferation with viability in orthovanadate and no EPO was reversible (Figure 1C). Aliquots of HCD57 cells cultured in the presence of 70 μmol/L orthovanadate were washed free of orthovanadate at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours and placed in fresh media containing EPO. At each time point up to 72 hours, the cells resumed a robust rate of cellular proliferation equal to the rate of proliferation before orthovanadate treatment. Between 72 and 96 hours of treatment with orthovanadate, proliferation resumed at approximately one half the rate of proliferation compared with recovery after 72 hours or less of treatment. This suggests cell damage may occur after 4 days of exposure to orthovanadate. Finally, we tested the hypothesis that orthovanadate might stop proliferation by inducing erythroid differentiation; however, we found no induction of alpha hemoglobin RNA, a marker of differentiation, at 24, 48, 72, or 96 hours after orthovanadate addition to the cells (data not shown). This suggests a lack of proliferation signaling in orthovanadate-treated cells that leads to a reversible cell cycle arrest in all phases of the cell cycle.

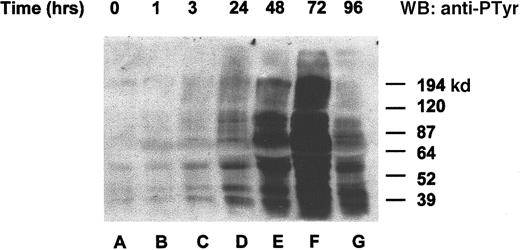

Orthovanadate increased the tyrosine phosphorylation state of many proteins

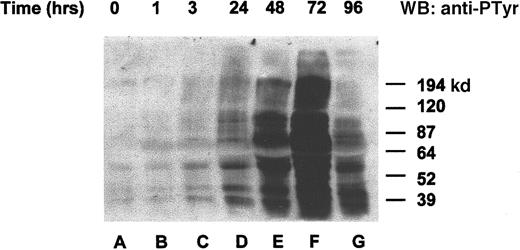

To determine whether the orthovanadate was truly acting as an inhibitor of tyrosine dephosphorylation, we chose to investigate overall changes in tyrosine protein phosphorylation after orthovanadate treatment. HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and treated with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (Figure 2). Whole cell extracts from 0 (lane A), 1 (lane B), 3 (lane C), 24 (lane D), 48 (lane E), 72 (lane F), and 96 (lane G) hours after orthovanadate treatment were analyzed by Western blot with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. Tyrosine phosphorylation of many proteins increased gradually within 24 hours. The phosphorylation continued to rise dramatically up to 72 hours of orthovanadate treatment and then began to fall by between 72 and 96 hours.

Orthovanadate increased tyrosine phosphorylation of many proteins.

HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and treated with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. Whole cell extracts from 0 (lane A), 1 (lane B), 6 (lane C), 24 (lane D), 48 (lane E), 72 (lane F), and 96 (lane G) were analyzed on a Western blot (WB) probed with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody as described in “Materials and methods.”

Orthovanadate increased tyrosine phosphorylation of many proteins.

HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and treated with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. Whole cell extracts from 0 (lane A), 1 (lane B), 6 (lane C), 24 (lane D), 48 (lane E), 72 (lane F), and 96 (lane G) were analyzed on a Western blot (WB) probed with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody as described in “Materials and methods.”

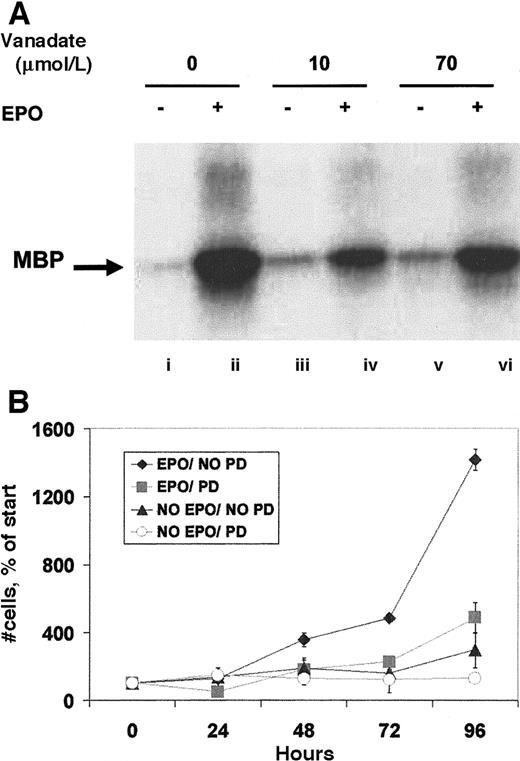

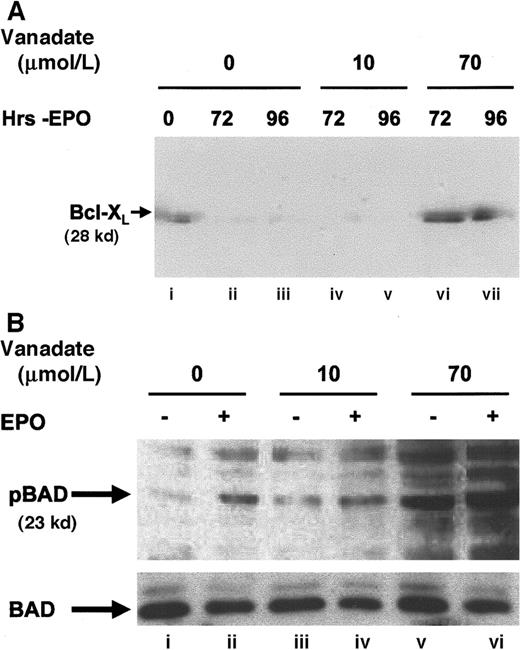

Orthovanadate maintained Bcl-XL levels and BAD phosphorylation

To further establish the nature of the protection from apoptosis provided, the expression of Bcl-XL (Figure3A), a protein known to protect HCD57 erythroid cells from apoptosis,32,33 was determined in cells cultured in 0, 10, or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate without EPO for 72 and 96 hours. Bcl-XL levels fell significantly within 24 to 72 hours when HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO.27 High Bcl-XL levels indicative of protection from apoptosis were maintained in both HCD57 cells in the presence of EPO (lane A) and in HCD57 cells deprived of EPO but cultured with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate for 96 hours (lane G). In contrast, cells deprived of EPO and cultured either without orthovanadate (lanes B and C) or with 10 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes D and E) had no detectable Bcl-XLlevels by 72 hours in culture. This suggests that orthovanadate protects from apoptosis at least in part by maintaining Bcl-Xl expression in the absence of EPO.

Orthovanadate maintains Bcl-XL levels and induces BAD phosphorylation.

(A) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (lane i), in the absence of EPO (lanes ii and iii), or in the absence of EPO and supplemented with 10 (lanes iv and v) or 70 μmol/L (lanes vi and vii) orthovanadate for 72 and 96 hours. Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with anti–Bcl-XL (Santa Cruz) antibody raised in rabbit. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with anti–Bcl-XL (UBI) antibody raised in mouse. (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv), or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells either were stimulated with 10 units EPO/mL (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–anti-phosphoBAD antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-BAD antibody.

Orthovanadate maintains Bcl-XL levels and induces BAD phosphorylation.

(A) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence of EPO (lane i), in the absence of EPO (lanes ii and iii), or in the absence of EPO and supplemented with 10 (lanes iv and v) or 70 μmol/L (lanes vi and vii) orthovanadate for 72 and 96 hours. Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with anti–Bcl-XL (Santa Cruz) antibody raised in rabbit. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with anti–Bcl-XL (UBI) antibody raised in mouse. (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv), or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells either were stimulated with 10 units EPO/mL (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–anti-phosphoBAD antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-BAD antibody.

Another member of the Bcl family of proteins, BAD, is antiapoptotic when phosphorylated. Our unpublished work shows that serine 112 but not the serine 136 residue of BAD is phosphorylated by EPO-induced signaling (Bao and Sawyer, 1999). In contrast, the unphosphorylated form of BAD, that results after growth factor withdrawal, heterodimerizes with Bcl-XL, to inhibit Bcl-XL,function, and therefore is proapoptotic.34 Western blot analysis of whole cell extracts with a phosphospecific antibody that recognizes the serine 112 residue of BAD when phosphorylated (Figure3B) confirmed an increase in BAD phosphorylation after EPO stimulation (lane B) and also showed that BAD was phosphorylated even more strongly after treatment with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lane E). In contrast, BAD was not phosphorylated after treatment with 10 μmol/L orthovanadate, a condition that did not protect cells from apoptosis. These results suggest a role for Bcl-XL and phosphorylation of the Bcl-XL inhibitor, BAD, in the action of 70 μmol/L orthovanadate to prevent apoptosis.

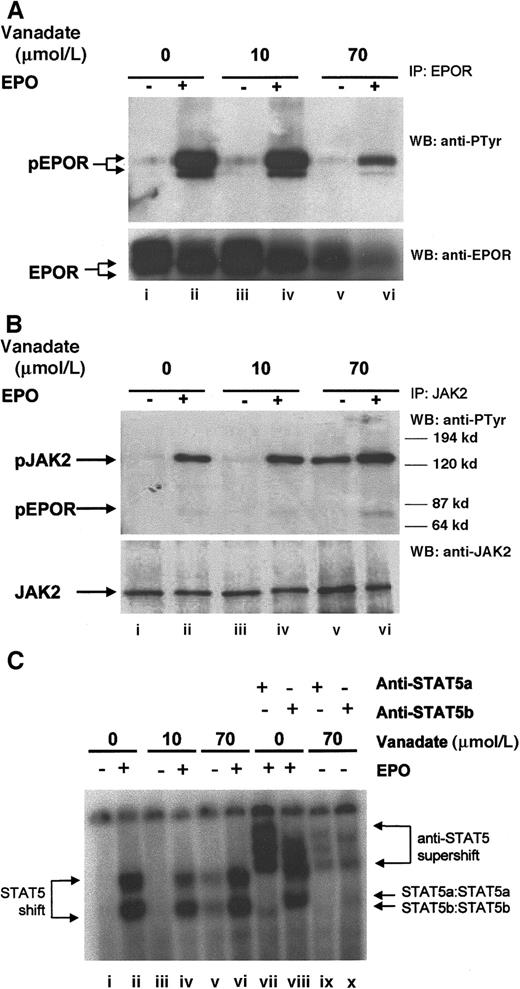

Orthovanadate activated JAK2 without tyrosine phosphorylation of the erythropoietin receptor

Next, we investigated the ability of 70 μmol/L orthovanadate to activate several important signal transduction molecules. As a control, we also investigated activation induced by 10 μmol/L orthovanadate, a concentration that was unable to prevent apoptosis. EPO treatment of erythroid cells leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of the EPOR,5 so we first evaluated the tyrosine phosphorylation state of the EPOR by immunoprecipitation with anti-EPOR antibody, followed by Western blotting with antiphosphotyrosine antibody (Figure4A, upper panel). HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO 24 hours to up-regulate the EPOR and then stimulated for 5 minutes with 10 units EPO per milliliter. Additionally, HCD57 cells deprived of EPO were also treated with either 10 or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate and then stimulated with EPO. Although EPO stimulation induced rapid phosphorylation of the EPOR (lane B), neither 10 μmol/L (lane C) nor 70 μmol/L (lane E) orthovanadate treatment induced phosphorylation. Probing the anti-EPOR immunoprecipitate with anti-EPOR antibody repeatedly and consistently showed that treatment with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate reduced up-regulation of EPOR expression somewhat, although other signaling molecules do not appear to be reduced by the same treatment (Figure 4A, lower panel, lanes E and F). Thus, orthovanadate does not activate the EPOR receptor to protect HCD57 cells from apoptosis.

Orthovanadate activates JAK2 and STAT5 but not EPOR.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv), or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with anti-EPOR antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot (WB) with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-EPOR antibody (lower panel). (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv) or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK2 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-JAK2 antibody (lower panel). (C) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0, 10, or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells then were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter or mock treated for 5 minutes. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with the STAT5 DNA binding sequence (PIE) for STAT5a/b DNA binding activity (lanes i-vi). Supershifts were performed with anti-STAT5a (lanes vii and ix) or anti-STAT5b (lanes viii and x) antibodies.

Orthovanadate activates JAK2 and STAT5 but not EPOR.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv), or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with anti-EPOR antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot (WB) with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-EPOR antibody (lower panel). (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv) or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Cell extracts were then immunoprecipitated with anti-JAK2 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot with antiphosphotyrosine antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-JAK2 antibody (lower panel). (C) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0, 10, or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells then were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter or mock treated for 5 minutes. Nuclear extracts were analyzed by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with the STAT5 DNA binding sequence (PIE) for STAT5a/b DNA binding activity (lanes i-vi). Supershifts were performed with anti-STAT5a (lanes vii and ix) or anti-STAT5b (lanes viii and x) antibodies.

JAK2 is a Janus kinase that associates with the EPOR and is involved in EPO signal transduction.6-9 Immunoprecipitation with anti-JAK2 antibody and subsequent antiphosphotyrosine Western blotting (Figure 4B) revealed that significant JAK2 activation was induced by either 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lane E) or EPO stimulation (lane B), but not by 10 μmol/L orthovanadate (lane C). The degree of JAK2 activation induced by 70 μmol/L orthovanadate was similar to that induced by EPO. Activation was specific to JAK2, as neither JAK1 nor Tyk2, other Janus kinase family members expressed in HCD57 cells, were activated by EPO or orthovanadate treatment (data not shown). Phosphorylated EPOR only coimmunoprecipitated with JAK2 after stimulation with EPO; treatment with orthovanadate did not induce EPOR to coimmunoprecipitate with JAK2. Therefore, orthovanadate-dependent JAK2 activation, independent of the activation of the EPOR, may activate survival signaling.

Orthovanadate induced STAT5 and STAT1 activation but not STAT3

JAK2 is upstream of STAT activation in many cells. EPO activates JAK2 and induces both STAT1 and STAT5 phosphorylation, nuclear localization, and DNA binding in primary murine erythroid cells and HCD57 cells.6 10 Western blotting of HCD57 nuclear extracts with anti-STAT5a and anti-STAT5b antibodies revealed nuclear translocation of both STAT5a and STAT5b after treatment of HCD57 cells with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate in the absence of EPO and after stimulation with EPO (data not shown). No such translocation was observed in the absence of EPO or after treatment with 10 μmol/L orthovanadate. STAT5 DNA binding activity measured by electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with the prolactin inducible element (PIE) (Figure 4C) also indicated that STAT5 was strongly activated by 70 μmol/L orthovanadate. Supershift analysis confirmed that STAT5a/STAT5b was indeed responsible for the DNA binding activity detected. In addition, we investigated STAT1 and STAT3 activation by EMSA using the SIE, to which both can bind (data not shown). Treatment with either EPO or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate, but not 10 μmol/L orthovanadate, induced SIE-DNA binding activity. Additional supershift analysis with anti-STAT1 and anti-STAT3 antibodies revealed this DNA binding activity was due to STAT1 and not STAT3. Thus, 70 μmol/L orthovanadate treatment activates a profile of STAT molecules (STAT1, STAT5A, and STAT5B) that mimics EPO treatment. A time course of STAT5 DNA binding activity (data not shown) revealed detectable activity within 6 hours. Activity peaked by 24 hours and dropped after 72 hours. Thus, STATs may be important in orthovanadate-dependent cell survival, but activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in the absence of other signals is insufficient to trigger proliferation.

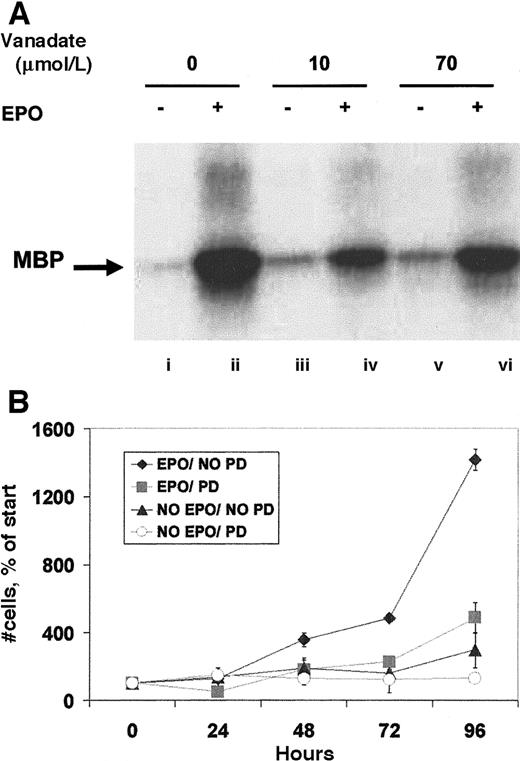

Orthovanadate did not significantly activate ERK or SHC

Other signaling molecules activated by EPO are ERK-1 and -2, members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family.13 After immunoprecipitation with anti-ERK antibody, an in vitro kinase assay to assess ERK activity (Figure5A) revealed that both 10 and 70 μmol/L orthovanadate equally induced only slight increases in activity. This faint activity was considerably lower by an order of magnitude than that induced by EPO. Next, we investigated the activation of SHC, a molecule phosphorylated by EPO and thought to be involved in the activation of ERK.11 Anti-SHC immunoprecipitate analyzed by antiphosphotyrosine Western blot revealed no detectable induction of tyrosine phosphorylation by 10 or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate of either the 47- or 52-kd SHC proteins (data not shown). SHIP, the phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate 5-phosphatase that interacts with SHC,12 was also not tyrosine phosphorylated by orthovanadate treatment. EPO stimulation, however, strongly activated both SHC and SHIP (data not shown). These data suggest a possible proliferative role for the MAPK pathway in erythroid cells that is not required for survival. Thus, we further tested this finding by treating HCD57 cells with the specific inhibitor of the MAPK pathway, PD98059. HCD57 cells were treated with 50 μmol/L PD98059 and the cells were counted after treatment for 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Addition of the MEK inhibitor significantly blocked proliferation of HCD57 cells, even in the presence of EPO (Figure 5B) but did not induce apoptosis (data not shown). This additional finding further supports a role for MAPK in EPO-dependent proliferation but not in protection from apoptosis.

Orthovanadate did not activate ERK-1 activity, and ERK activity is required for proliferation.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv) or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). ERK-1 was immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts; activity was determined by the phosphorylation of myelin basic protein in an in vitro kinase assay. (B) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of EPO and in the presence or absence of 50 μmol/L PD98059, MEK inhibitor to block ERK activity. Cells were counted at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 4 determinations.

Orthovanadate did not activate ERK-1 activity, and ERK activity is required for proliferation.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv) or 70 (lanes v and vi) μmol/L orthovanadate. The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). ERK-1 was immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts; activity was determined by the phosphorylation of myelin basic protein in an in vitro kinase assay. (B) HCD57 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of EPO and in the presence or absence of 50 μmol/L PD98059, MEK inhibitor to block ERK activity. Cells were counted at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours. Viability was determined using trypan blue exclusion. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of 4 determinations.

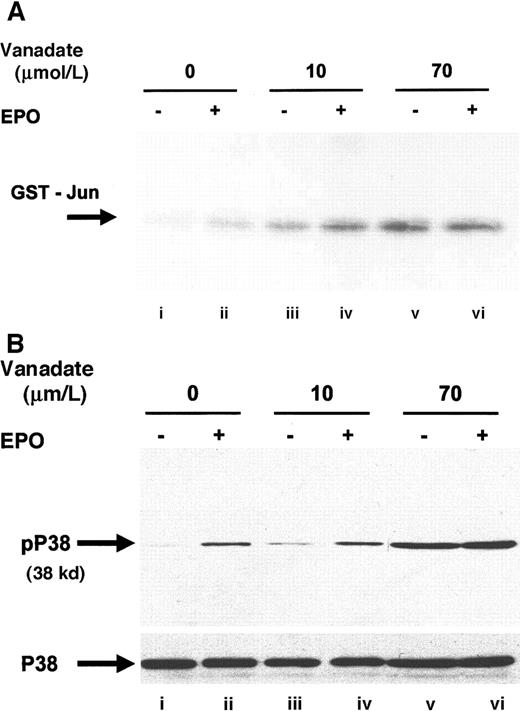

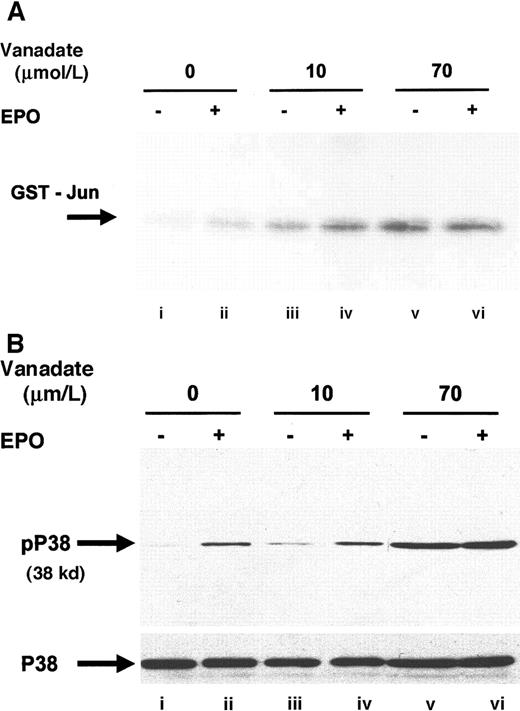

Orthovanadate activated JNK and p38

Next, we investigated JNK-1 activity. JNK is a member of the stress activated protein kinase family (SAPK) and is responsible for the phosphorylation of the amino terminal of the AP-1 transcription factor c-jun.35 EPO stimulation has previously been shown to phosphorylate JNK-1 and -2 and to induce JNK activity in HCD57 cells.27 JNK activity was assessed by immunoprecipitation with anti–JNK-1 antibody, followed by an in vitro kinase assay that detects the ability of JNK to phosphorylate recombinant glutathione-S-transferase (GST)–c-jun (Figure6A). Both 10 (lane C) and 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lane E) significantly stimulated JNK-1 activity; however, treatment with 70 μmol/L induced greater activation than treatment with 10 μmol/L. Activation of JNK by 10 μmol/L orthovanadate suggested that JNK activation is not sufficient for protection from apoptosis, but this finding did not preclude a requirement for JNK in the protection from apoptosis. EPO stimulation also induces activation of another SAPK, p38,15 49 so we chose to investigate whether orthovanadate could also induce p38 activation. Western blot with a phosphospecific p38 antibody showed induction of p38 activation after EPO stimulation (Figure 6B, lane B) and treatment with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lane E). Whereas this suggested a possible role of p38 activity in orthovanadate-dependent cell survival, we tested if inhibition of p38 activity triggered apoptosis. Using the p38 inhibitor, SB203580, we found that inhibition of p38 activity did not induce the HCD57 cells into apoptosis (data not shown). Thus orthovanadate-induced p38 activity alone does not allow cell survival and p38 signals alone cannot promote proliferation.

Orthovanadate activates JNK-1 and p38.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 μmol/L (lanes iii and iv) or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes v and vi). The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). JNK-1 was immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts; activity was determined by the phosphorylation of GST-Jun in an in vitro kinase assay. (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 μmol/L (lanes iii and iv) or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes v and vi). The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–phospho-p38 antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-p38 (lower panel) antibody.

Orthovanadate activates JNK-1 and p38.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 μmol/L (lanes iii and iv) or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes v and vi). The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). JNK-1 was immunoprecipitated from the cell extracts; activity was determined by the phosphorylation of GST-Jun in an in vitro kinase assay. (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 μmol/L (lanes iii and iv) or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes v and vi). The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–phospho-p38 antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-p38 (lower panel) antibody.

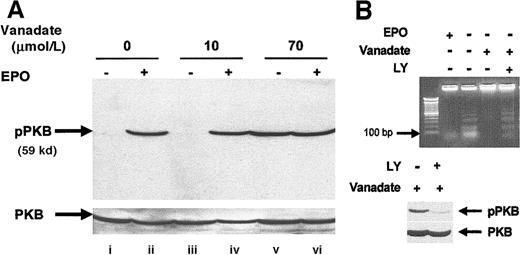

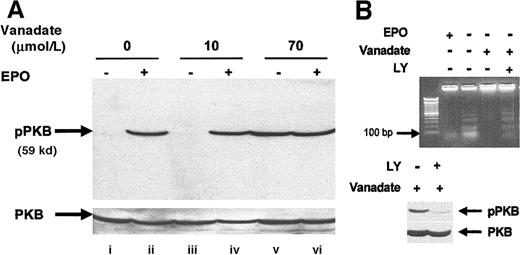

Orthovanadate activated PI-3 kinase/PKB/Akt

We investigated activation of the PI-3 kinase pathway by analyzing activation of PKB/Akt, a molecule that is activated downstream of PI-3 kinase after EPO stimulation of HCD57 cells.36 Analysis of whole cell extracts by Western blot using an activation-specific antibody that recognizes PKB/Akt when phosphorylated at serine 473 (Figure 7A) showed that both EPO (lane B) and 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lane E) induced PKB/Akt phosphorylation but no effect was seen with the nonprotective 10 μmol/L orthovanadate treatment. To determine whether the activation observed was indeed necessary for protection from apoptosis, we treated HCD57 cells deprived of EPO but supplemented with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate for 24 hours with 50 μmol/L LY294002, a PI-3 kinase inhibitor for an additional 24 hours. This inhibitor blocked activation of PKB/Akt by orthovanadate (Figure 7, lower panel). Cells treated with orthovanadate showed intact genomic DNA, whereas cells treated with both orthovanadate and LY294002 showed a significant apoptosis as indicated by laddering of the genomic DNA (lane D) equivalent to the degradation observed in the absence of EPO and orthovanadate (lane B) (Figure 7B, upper panel). Thus, PI-3 kinase activity induced by orthovanadate treatment is apparently required for HCD57 cell survival in the absence of EPO.

Orthovanadate activates the PI-3 kinase/PKB/Akt cascade and PI-3 kinase activity is required for survival in orthovanadate-treated HCD57 cells.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv) or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes v and vi). The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–phospho-PKB/Akt antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-PKB/Akt antibody (lower part of panel) as a loading control. (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and treated with 50 μmol/L orthovanadate for 24 hours. The 50 μmol/L LY294002 was added to one aliquot of these cells for the 24-hour interval. For each aliquot, 10 μg of genomic DNA was analyzed by agarose gel for fragments of DNA characteristic of apoptosis (upper panel). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–phospho-PKB/Akt antibody (lower panel). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-PKB/Akt antibody as a loading control (bottom of lower panel).

Orthovanadate activates the PI-3 kinase/PKB/Akt cascade and PI-3 kinase activity is required for survival in orthovanadate-treated HCD57 cells.

(A) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and cultured 24 hours in 0 (lanes i and ii), 10 (lanes iii and iv) or 70 μmol/L orthovanadate (lanes v and vi). The cells were either stimulated with 10 units EPO per milliliter (lanes ii, iv, and vi) or mock treated for 5 minutes (lanes i, iii, and v). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–phospho-PKB/Akt antibody. The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-PKB/Akt antibody (lower part of panel) as a loading control. (B) HCD57 cells were deprived of EPO and treated with 50 μmol/L orthovanadate for 24 hours. The 50 μmol/L LY294002 was added to one aliquot of these cells for the 24-hour interval. For each aliquot, 10 μg of genomic DNA was analyzed by agarose gel for fragments of DNA characteristic of apoptosis (upper panel). Whole cell extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti–phospho-PKB/Akt antibody (lower panel). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-PKB/Akt antibody as a loading control (bottom of lower panel).

Discussion

We report here that treatment of HCD57 cells with 50 μmol/L to 70 μmol/L orthovanadate in the absence of EPO results in strong and sustained tyrosine protein phosphorylation, due to an inhibition of tyrosine phosphatase activity. This orthovanadate treatment provided protection from apoptosis in the absence of EPO without promotion of proliferation. It is notable that the combination of 70 μmol/L orthovanadate and EPO triggered apoptosis of HCD57 cells (not shown), suggesting that orthovanadate can also trigger apoptosis by altering (perhaps by overstimulating) signal transduction in the presence of EPO. Orthovanadate was also able to delay apoptosis in normal EPO-dependent human erythroid progenitor cells after EPO withdrawal. Thus, the effect of orthovanadate seen in the erythroleukemic HCD57 cells is most likely a general phenomena and not due to a mutation present only in these cells.

Orthovanadate activated several signal transduction molecules in HCD57 cells that are also activated by EPO, including JAK2, STAT5, ERK, JNK, p38, and PKB/Akt. Other molecules, including the EPOR, SHC, and SHIP, that are activated by EPO were not activated by orthovanadate. Table2 summarizes the activation of several signal transduction molecules when HCD57 cells are treated with EPO, different concentrations of orthovanadate, or SCF36,37(unpublished data by Bao and Sawyer, 1999, and unpublished data by Jacobs-Helber and Sawyer, 1999). Examination of this table suggests that a subset of signal transduction molecules could be responsible for protection from apoptosis in HCD57 cells treated with orthovanadate. One strong possibility is the JAK2/STAT5 pathway. Strong evidence currently exists to link JAK2 to protection from apoptosis. For example, a dominant negative JAK2 prevented EPO-dependent protection from apoptosis.9 Additionally, JAK2 signals, even in the absence of many other signals, can prevent gamma-irradiation–induced apoptosis in hematopoietic progenitors.38 Knockout of JAK2 in mice is an embryonic lethal phenotype that also causes a defect in definitive erythropoiesis.39 JAK2 signals were absent in HCD57 cells treated with SCF, a treatment that promotes proliferation but not protection from apoptosis.37

Whereas the potential roles of STAT5 in protection from apoptosis and in promotion of proliferation have been the targets of many careful and extensive investigations, the role of STAT5 remains controversial. Some publications implicate STAT5 as an antiapoptotic protein,40,41 whereas other findings link STAT5 activation instead with proliferation.42,43 SCF, which promotes proliferation in HCD57 cells, did not activate STAT5, indicating that STAT5 was not essential for proliferation in these cells.37 The study of STAT5A/B −/− mice by Teglund et al44 showed a variety of defects, none of which was in erythropoiesis. This suggested a nonessential role of STAT5 in both survival and proliferation of erythroid cells; however, a recent report showed that the STAT5A/B −/− embryos were anemic.45These workers also reported in an abstract that STAT5A/B−/− mice failed to return to a normal hematocrit as quickly as wild-type mice after induction of hemolytic anemia by phenyl hydrazine. Thus, there may be a role of STAT5 in the survival of erythroid cells that is only apparent in mice under stress. Socolovsky et al45 also reported a critical role for STAT5 in the induction of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-XL. Moreover, Silva et al46 recently provided a study that showed STAT5 is involved in Bcl-XL expression in HCD57 cells. The results support the possibility that STAT5 activity induced by orthovanadate acts to maintain Bcl-XL expression, promoting cell survival.

The EPOR was not tyrosine phosphorylated by orthovanadate treatment, even though JAK2 was activated. Orthovanadate likely does not induce EPOR dimerization, which is believed to be important for EPO signal transduction.47 In a previous study, orthovanadate was shown to induce phosphorylation of the immature form of EPOR in the endoplasmic reticulum; however, this study used a toxic concentration of perorthovanadate, 1 mmol/L, in Ba/F3 cells.48

MAPK/ERK was only slightly activated by both 10 and 70 μmol/L orthovanadate to a level an order of magnitude less than EPO, suggesting the MAP kinase cascade is not required for protection from apoptosis induced by orthovanadate. The MEK inhibitor PD98059 that specifically blocks the downstream MAPK pathway decreased proliferation in EPO without induction of apoptosis. The data suggest that the lack of activation of the MAPK cascade by orthovanadate is likely the reason that treatment of HCD57 cells with this phosphatase inhibitor does not stimulate proliferation. Orthovanadate treatment did not block the cell cycle; therefore, it seems most probable that proliferation signals are not appropriately activated by orthovanadate.

JNK and p38 were also activated by treatment with 70 μmol/L orthovanadate in the HCD57 cells. In contrast, JNK was also activated to similar degrees by 10 μmol/L orthovanadate treatment, which did not protect from apoptosis. This finding indicates that activation of JNK is not sufficient for protection from apoptosis. JNK may be involved in proliferation, as JNK was activated in SCF-induced proliferation of HCD57 cells.37,49 p38 was not activated by 10 μmol/L orthovanadate; however, inhibition of p38 activity failed to support a role of p38 in survival. A recent report claimed that both JNK and p38 activities in HCD57 cells correlated with cell death.50 Our data here is in direct contradiction to this hypothesis. We find that orthovanadate treatment induced high levels of JNK and p38 activity without inducing cell death in HCD57 cells. We have recently reexamined the activity of JNK and p38 after EPO withdrawal to induce apoptosis in HCD57 cells. We find both JNK and p38 continuously active in the presence of EPO; when EPO is withdrawn to induce apoptosis, both JNK and p38 activities fall to undetectable levels.49

The activation of the PI-3 kinase pathway by orthovanadate treatment appears to be necessary for the survival of HCD57 cells, because we observed that the PI-3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 triggered apoptosis in the presence of orthovanadate (and absence of EPO) to a similar extent as apoptosis induced by withdrawal of EPO in the absence of orthovanadate. We have previously reported that constitutively active PI-3 kinase is critical for the survival of a subclone of HCD57 (HCD57-SREI) cells that had become EPO independent.36 In contrast, EPO-induced signaling apparently can promote survival of HCD57 in the absence of PI-3 kinase activity, because HCD57 cells undergo little if any apoptosis in high concentrations of LY294002 when EPO is constantly present.36 The role of PKB/Akt downstream of PI-3 kinase in survival is not as clear. We suspect that PKB/Akt is not a central factor in survival because we previously observed the inability of SCF to protect HCD57 from apoptosis yet observed that SCF activated PKB/Akt equally well as either EPO or orthovanadate.36 It is possible that orthovanadate activated PI-3 kinase and a downstream kinase that phosphorylates BAD at serine 112. PKB/Akt is a kinase that recognizes only serine 136 of BAD but other kinases such as PKA, MAPK, and other as yet unknown kinases may phosphorylate BAD at serine 112 in response to survival signals. EPO treatment or orthovanadate treatment of HCD57 cells activates at least one serine 112 BAD kinase (Figure 3B).

In summary, the JAK/STAT signaling cascade appears anti-apoptotic (prosurvival), as it is strongly activated by orthovanadate but not by SCF. Recent papers reporting a role of STAT5 in Bcl-XLexpression suggest that activation of STAT5 by orthovanadate may act to maintain the expression of Bcl-XL that is critical for the cell to survive in the absence of EPO. The MAPK signaling pathway is most likely proliferative, as it is strongly activated by SCF but not by orthovanadate. Treatment with the inhibitor PD98059, an inhibitor of the MAPK pathway, dramatically slowed HCD57 proliferation without inducing apoptosis, further supporting the argument that the MAPK pathway is a proliferative signal. Finally, the PI-3 kinase pathway may be both antiapoptotic and proliferative. Either orthovanadate or SCF treatment activates the PI-3 kinase/PKB/Akt pathway. Treatment with the PI-3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 both slowed proliferation in EPO-treated cells and disrupted orthovanadate's ability to protect from apoptosis. It is likely, however, that the EPO signaling pathway is sufficiently redundant and complex that PI-3 kinase is not a requirement for EPO-dependent survival, but PI-3 kinase signaling can provide a protection against apoptosis when activated by external or internal factors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr John Ryan for his kind assistance with flow cytometry and Dr Paul Dent for his gift of GST-jun. The data in this paper were included in a dissertation by Amy E. Lawson to partially satisfy the requirements of the MD/PhD degree of the Medical College of Virginia Campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01DK39781 (S.T.S).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Stephen T. Sawyer, Box 980613, MCV Station, Department of Pharmacology/Toxicology, Richmond, VA 23298; e-mail:ssawyer@hsc.vcu.edu.