Abstract

Perforin (pfp) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) together in C57BL/6 (B6) and BALB/c mouse strains provided optimal protection in 3 separate tumor models controlled by innate immunity. Using experimental (B6, RM-1 prostate carcinoma) and spontaneous (BALB/c, DA3 mammary carcinoma) models of metastatic cancer, mice deficient in both pfp and IFN-γ were significantly less proficient than pfp- or IFN-γ–deficient mice in preventing metastasis of tumor cells to the lung. Pfp and IFN-γ–deficient mice were as susceptible as mice depleted of natural killer (NK) cells in both tumor metastasis models, and IFN-γ appeared to play an early role in protection from metastasis. Previous experiments in a model of fibrosarcoma induced by the chemical carcinogen methylcholanthrene indicated an important role for NK1.1+ T cells. Herein, both pfp and IFN-γ played critical and independent roles in providing the host with protection equivalent to that mediated by NK1.1+ T cells. Further analysis demonstrated that IFN-γ, but not pfp, controlled the growth rate of sarcomas arising in these mice. Thus, this is the first study to demonstrate that host IFN-γ and direct cytotoxicity mediated by cytotoxic lymphocytes expressing pfp independently contribute antitumor effector functions that together control the initiation, growth, and spread of tumors in mice.

Introduction

Considerable attention has been paid to the direct antitumor activities of cytotoxic lymphocytes within innate and acquired components of the cellular immunity.1 However, until recently, little information was available regarding the relative role of direct cytotoxicity in immunity against tumor development. The development of gene-targeted mice deficient in perforin (pfp)2 and the discovery of several members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily with the capacity to induce tumor cell apoptosis3-5 have paved the way to determining which effector molecules are relevant in tumor immune surveillance. Thus far, in mouse experimental tumor systems, pfp has been demonstrated to protect the host against tumor initiation,6 primary tumor growth,6,7 and tumor metastasis.8 Perforin enables the entry of granzymes that play a key role in target cell DNA fragmentation, but these serine esterases are not critical for tumor cell death mediated by effector cells.9,10 Concerning innate cytotoxicity mediated by NK cells, a role for Fas ligand (FasL) and other TNF family members in tumor immune surveillance is less obvious. Notably, in some models involving innate antitumor activity, natural killer (NK) cell-depleted mice were often significantly more susceptible to tumor metastasis than pfp-deficient mice, despite the lack of activity of FasL or TNF against these tumors in vivo.8 These observations suggested that other pfp-independent effector functions may be contributing to tumor protection.

In this light, IFN-γ is a pleiotropic cytokine that plays a central role in innate and adaptive arms of host immune defense.11,12 IFN-γ is secreted by NK cells and thymus-derived T cells under certain conditions of activation.13,14 IFN-γ acts in various ways on host and tumor cells to favor tumor regression, but the relative role that IFN-γ plays in antitumor responses, compared with direct cytotoxicity by effector molecules such as pfp, has not been previously evaluated. Two studies have elegantly demonstrated a role for IFN-γ in tumor immune surveillance15 16; however, neither of these determined how important IFN-γ function was compared with direct cytotoxicity mediated by innate effector cells. Herein, we have undertaken the first study to compare directly the relative role of pfp and IFN-γ in 3 distinct models of tumor immunity. The 3 tumor models used are distinguished by different relative contributions of NK cells and NK1.1+ T (NKT) cells in host protection. Regardless of the relative role of NK and NKT cells, the creation of mice doubly deficient for pfp and IFN-γ has demonstrated that these 2 effector arms can act independently and equally effectively yet together account for all the natural antitumor immunity mediated by NK and NKT cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

Inbred C57BL/6, BALB/c, and BALB/c SCID mice were purchased from The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Melbourne, Australia). BALB/c.B6Cmv1r (NK1.1+) were obtained from the Animal Resources Centre (Perth, Australia). The following gene-targeted mice were bred at the Austin Research Institute Biological Research Laboratories (ARI-BRL): C57BL/6.IFN-γ–deficient (B6.IFN-γ0) (kindly provided by Genentech, San Francisco, CA)17; C57BL/6.perforin-deficient (B6.pfp0) mice2 (from Dr Guna Karupiah, John Curtin School of Medical Research, Canberra, Australia); C57BL/6.IL-12p40–deficient (B6.IL-12p400) mice18 (from Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ); C57BL/6.RAG-1–deficient (B6.RAG-10) mice (from Dr Lynn Corcoran, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research); C57BL/6.T-cell receptor (TCR).Jα281-deficient (B6.Jα2810) mice (from Dr Masaru Taniguchi, Chiba University School of Medicine, Chiba, Japan)19; C57BL/6.gld (FasL mutant); BALB/c.perforin-deficient (BALB/c.pfp0),8 and BALB/c.IFN-γ–deficient (BALB/c.IFN-γ0).17 C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice doubly deficient for perforin and IFN-γ (B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0, BALB/c.pfp0.IFN-γ0) were produced and bred at the ARI-BRL. Mice of 4 to 8 weeks of age were used in all experiments, performed according to animal experimental ethics committee guidelines.

Cell culture and chromium 51Cr release assays

The mouse tumor cell lines and spleen cell cultures used in this study were maintained as previously described.8,19,20Cytotoxicity of freshly isolated mouse spleen cells or IL-2–activated adherent NK cells (greater than 80% NK1.1+TCRβ−) from wild-type or gene-targeted mice were assessed by 4-hour chromium 51Cr release assays against labeled targets as described.7 Each experiment was performed twice with at least 4 different effector–target ratios using duplicate samples.

Subset depletion

The protocols for depletion of NK1.1+ (NK and NKT) cells in B6 mice using anti-NK1.1 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (PK136) were as previously described.8,19 Groups of BALB/c and BALB/c.B6Cmv1r (NK1.1+) mice were depleted of asialo GM1+ cells using the rabbit anti-asialo GM1 antibody (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) as described.8The BALB/c.B6Cmv1r (NK1.1+) mice were used to show that this depletion was effective because DX5 and other markers are not entirely suitable for detecting NKT cells. Anti-asialo GM1 antibody depleted NK1.1+TCRβ− NK cells, but not NK1.1+TCRβ+ NK) T cells (Table1). Assessment of depletion was performed after the preparation of cell suspensions from spleen and liver as described.21 Flow cytometry of cells was performed with allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-αβTCR (clone H57-597) and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-NK1.1, purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Tumor surveillance in vivo

Effector function was examined in 3 different tumor models (RM-1, DA3, and methylcholanthrene [MCA] induction of fibrosarcoma), as described, using gene-targeted mice or mice depleted of lymphocyte subsets.8,19 In the RM-1 model, mice were injected subcutaneously with RM-1 tumor cells (2 × 106), and tumors were established for 9 days. At this time, subcutaneous tumors were surgically resected, and fresh in vitro cultured RM-1 cells were injected through the dorsolateral tail vein. Mice were killed 14 days later, the lungs were removed and fixed in Bouin's solution, and surface lung metastases were counted blinded with the aid of a dissecting microscope. Additionally, in the RM-1 tumor model, groups of B6 mice were treated with rat antimouse IFN-γ mAb (R4-6A2) or control rat IgG1 (R3-34; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) (500 μg each) on days −2, 0 (day of intravenous tumor inoculation), 2, 7, and 10. Some mice received anti–mIFN-γ mAb early (days −2, 0) and others late (days 7, 10). Protocols that have used similar concentrations and conditions have been shown to effectively inhibit mIFN-γ activity in vivo.22 Data were recorded as the mean number of metastases ± SEM. Significance was determined by a Mann-WhitneyU (rank sum) test.

Results

NK and NKT cell number and NK cytotoxic function in gene-targeted mice

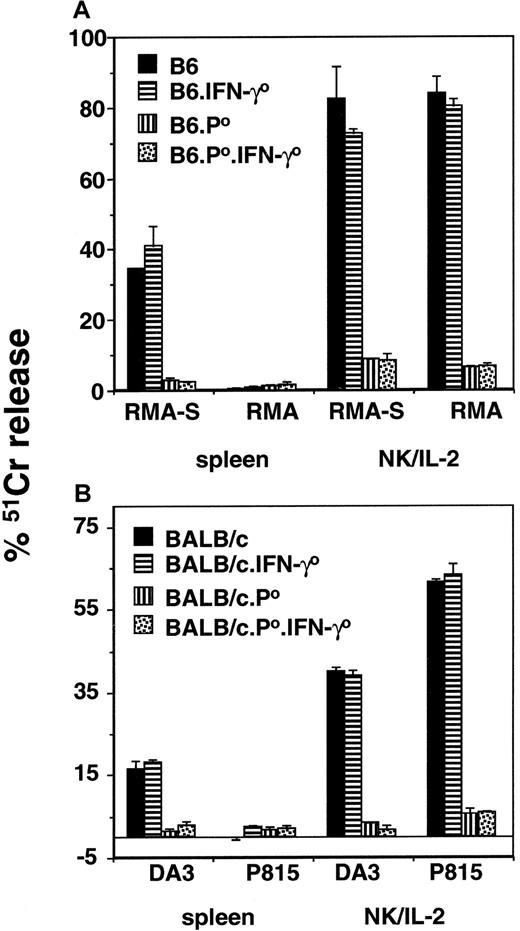

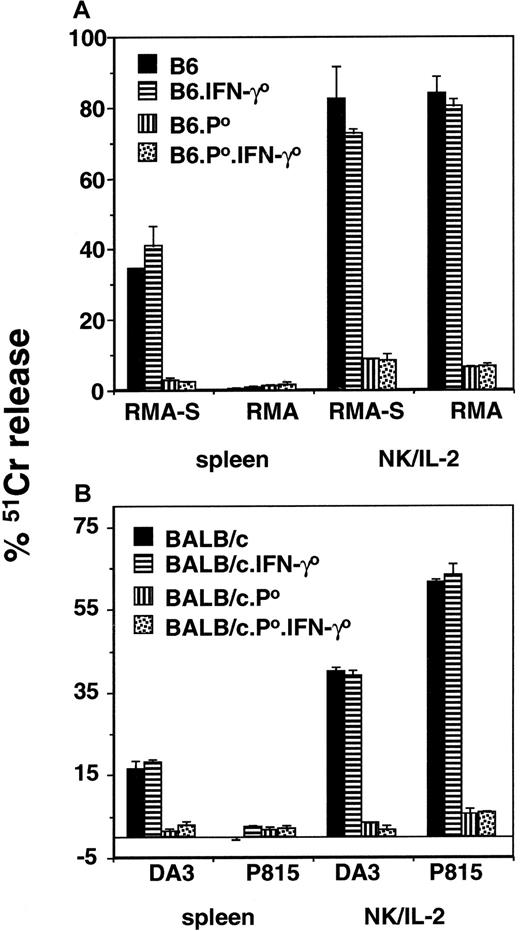

Multiparameter flow cytometry was used to examine the status of NK and NKT cells in the various mouse strains in this study. To use the NK1.1 marker, B6 strains were examined. Cell suspensions were made from thymus, spleen, liver, bone marrow, lymph nodes, and peritoneal exudate cells. As expected, NK1.1+ cells were detected in each organ and included both αβTCR− (NK cells) and αβTCR+ (NKT cells). Both NK and NKT cells were clearly present in the appropriate organs of wild-type, B6.IFN-γ0, B6.pfp0, and B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0 strains (data not shown). Next, the cytotoxic function of NK cells in both B6 and BALB/c gene-targeted mice was examined in a 4-hour 51Cr release assay against class 1–deficient, NK-sensitive targets (RMA-S and DA3) and class 1–expressing targets (RMA and P815) (Figure1A-B). In both strains (B6 and BALB/c), freshly isolated splenocytes or IL-2–activated adherent NK cells (greater than 80%) from the spleen of wild-type or IFN-γ0 mice displayed NK and LAK activity (Figure 1A-B). By contrast, resting or IL-2–activated adherent NK cells from the spleen of pfp0 or pfp0.IFN-γ0mice displayed little or no NK and LAK activity (Figure 1A-B). These data confirmed that pfp, but not IFN-γ, was critical for direct cytotoxicity by NK cells.

NK-cell–mediated cytotoxicity of pfp and IFN-γ gene-targeted mice.

Resting splenocytes and IL-2–activated adherent spleen NK cells were assessed by 4-hour 51Cr release assays using labeled targets as indicated for (A) B6 or (B) BALB/c strains of mice. An effector–target ratio of 100:1 is shown (4 were examined). The spontaneous release of 51Cr was always less than 15% (subtracted from test), and each experiment was performed twice using triplicate samples.

NK-cell–mediated cytotoxicity of pfp and IFN-γ gene-targeted mice.

Resting splenocytes and IL-2–activated adherent spleen NK cells were assessed by 4-hour 51Cr release assays using labeled targets as indicated for (A) B6 or (B) BALB/c strains of mice. An effector–target ratio of 100:1 is shown (4 were examined). The spontaneous release of 51Cr was always less than 15% (subtracted from test), and each experiment was performed twice using triplicate samples.

NK cell–mediated control of spontaneous metastasis by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities

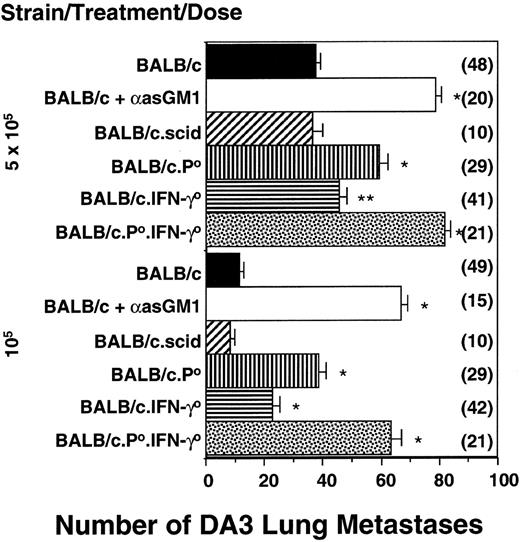

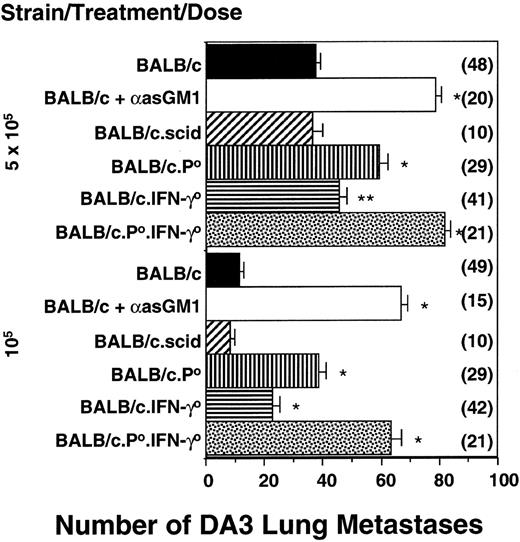

The relative importance of pfp and IFN-γ was next examined in a model of spontaneous metastasis that is strictly controlled by NK cells.8 Two different DA3 tumor doses (105 and 5 × 105) were inoculated subcutaneously, and after 42 days, lung metastases were counted. There were significantly increased numbers of metastases in BALB/c.pfp0 mice or BALB/c.IFN-γ0 mice compared with wild-type BALB/c mice, but fewer than found in NK cell–depleted (anti-asialo GM1-treated) mice (Figure 2). Anti-asialo GM1 antibody depletion was complete and specific for NK cells and did not effectively deplete NKT- or T-cell populations (Table 1). Similar increases in DA3 lung metastasis were observed in BALB/c.B6Cmv1r mice depleted with anti-asialo GM1 antibody (Figure 2 legend). There was no increase in DA3 metastases in T-cell– and NKT-cell–deficient BALB/c.SCID mice (Figure 2). Importantly, BALB/c.pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice were as susceptible to tumor metastasis as NK-cell–depleted mice. In addition, qualitatively equivalent results were obtained in mice simply injected intravenously with DA3 tumor cells (data not shown), suggesting that pfp and IFN-γ were both protecting against tumor cell engraftment in the lung rather than migration from the subcutaneous site of inoculation.

NK-cell–mediated control of spontaneous metastasis by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities.

BALB/c, BALB/c.SCID, BALB/c.IFN-γ0, BALB/c.pfp0, and BALB/c pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice or BALB/c mice treated with anti-asialo GM1 antibody (100 μg/injection) were inoculated subcutaneously with DA3 tumor cells (105 or 5 × 105) as indicated. Mice depleted of subsets in vivo were treated on days −4, 0 (day of subcutaneous tumor inoculation), and weekly thereafter. Forty-two days after tumor inoculation, the lungs of these mice were harvested and fixed, and colonies were counted and recorded as the mean number of colonies ± SE. Asterisks indicate the groups that are significantly different from BALB/c-untreated mice (*P < .0001; **P < .005; Mann-Whitney U test). A significant difference was also detected between the BALB/c.P0 mice or BALB/c.IFN-γ0 mice and BALB/cP0.IFN-γ0 mice (P < .0001). The number of mice per group is shown in parentheses. Note that for groups of 5 mice receiving 105DA3 tumor cells, the numbers of DA3 lung colonies were as follows: BALB/c.B6Cmv1r = 8.0 ± 2.6; BALB/c.B6Cmv1r + anti-asialo GM1 antibody = 62.4 ± 6.6.

NK-cell–mediated control of spontaneous metastasis by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities.

BALB/c, BALB/c.SCID, BALB/c.IFN-γ0, BALB/c.pfp0, and BALB/c pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice or BALB/c mice treated with anti-asialo GM1 antibody (100 μg/injection) were inoculated subcutaneously with DA3 tumor cells (105 or 5 × 105) as indicated. Mice depleted of subsets in vivo were treated on days −4, 0 (day of subcutaneous tumor inoculation), and weekly thereafter. Forty-two days after tumor inoculation, the lungs of these mice were harvested and fixed, and colonies were counted and recorded as the mean number of colonies ± SE. Asterisks indicate the groups that are significantly different from BALB/c-untreated mice (*P < .0001; **P < .005; Mann-Whitney U test). A significant difference was also detected between the BALB/c.P0 mice or BALB/c.IFN-γ0 mice and BALB/cP0.IFN-γ0 mice (P < .0001). The number of mice per group is shown in parentheses. Note that for groups of 5 mice receiving 105DA3 tumor cells, the numbers of DA3 lung colonies were as follows: BALB/c.B6Cmv1r = 8.0 ± 2.6; BALB/c.B6Cmv1r + anti-asialo GM1 antibody = 62.4 ± 6.6.

NK- and NKT-cell–mediated control of experimental tumor metastasis by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities

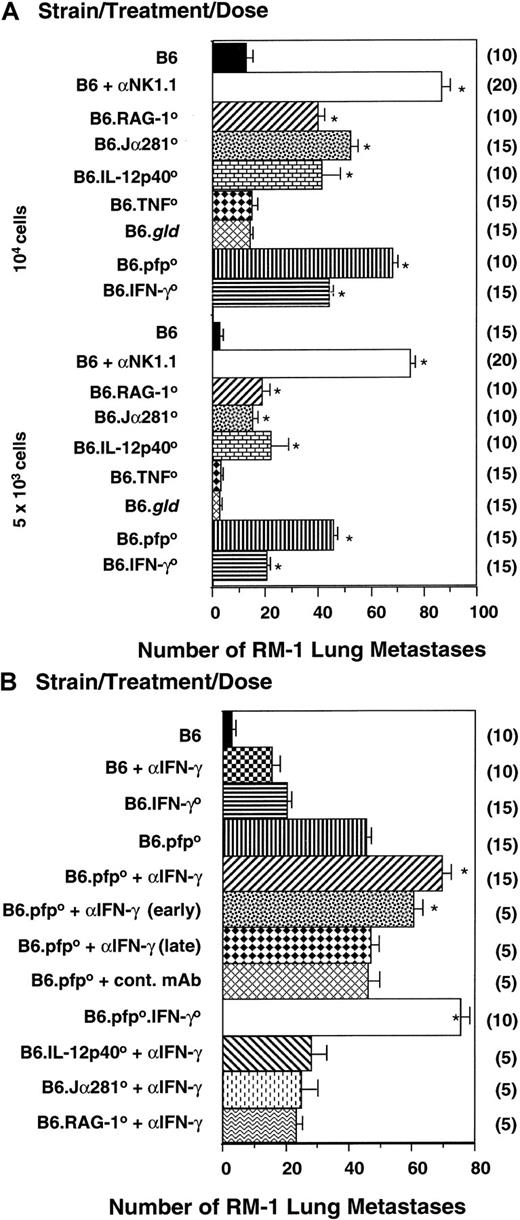

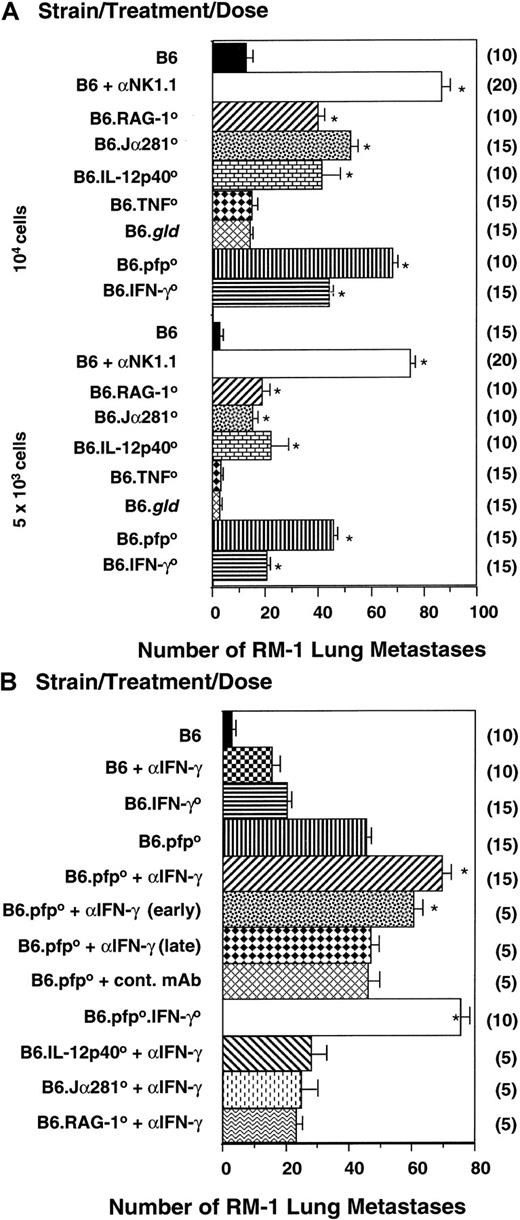

Innate protection from metastasis was then examined in the B6 RM-1 tumor model in which NK and NKT cells have previously been shown to control tumor metastasis.8,19 Confirming previous reports, B6 mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells displayed a significantly higher number of RM-1 lung metastases than B6 mice deficient for T cells and NKT cells (RAG-10) or NKT cells alone (Jα2810) (Figure3A). These data suggested that NK cells were the primary effector population, but clearly NKT cells play some role in RM-1 tumor protection because Jα2810 mice displayed significantly more metastases than untreated B6 mice. The major effector molecules involved in host protection were pfp, IL-12, and IFN-γ, as evidenced by the significant increase in RM-1 lung metastases in mice deficient for each of these molecules (Figure 3A). Nevertheless, B6.pfp0, B6.IL-12p400, and B6.IFN-γ0 mice had significantly fewer RM-1 lung colonies than B6 mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells (Figure 3A). In this model, we have already demonstrated that B6.pfp0 mice or B6.IFN-γ0mice treated with anti-NK1.1 mAb do not develop more metastases than B6 mice treated with anti-NK1.1 mAb; thus, pfp and IFN-γ activities are not independent of NK cell function.23 Although IFN-γ can clearly potentiate the apoptotic activity of TNF superfamily molecules,12 including TNF-related, apoptosis-inducing ligand24 (not assessed herein), no apparent role for FasL or TNF effector molecules was observed in this model of metastases (Figure 3A).

NK- and NKT-cell–mediated control of experimental tumor metastasis by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities.

(A) B6, B6.pfp0, B6.RAG-10, B6.TNF0, B6.IFN-γ0, and B6.gldmice or B6 mice treated with anti-NK1.1 were inoculated subcutaneously between the shoulder blades with RM-1 tumor cells (2 × 106), and tumors were allowed to establish for 9 days. Subcutaneous tumors were then resected and a dose range of RM-1 cells (as indicated) injected through the tail vein. Mice were killed 14 days later, the lungs were removed and fixed, and colonies were counted and recorded as the mean number of colonies ± SE. A group of B6 mice was depleted of NK1.1+ cells in vivo by mAb treatment (100 μg/injection) on days −2, 0 (day of intravenous tumor inoculation), 2, and 9. (B) B6, B6.pfp0, B6.IFN-γ0, and B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0mice or B6 and B6.pfp0 mice treated with anti–mIFN-γ mAb (500 μg/injection) or control mAb (500 μg/injection) were treated as above. Mice received anti–IFN-γ mAb on days −2, 0 (day of intravenous tumor inoculation), 2, 7, and 10, with some groups receiving anti–mIFN-γ mAb early (days −2, 0) or late (days 7, 10). (A) Significant differences from the B6 group were determined by a Mann-Whitney U test (*P < .0001). Additionally, mice treated with anti-NK1.1 had significantly more metastases than any other group, including B6.pfp0 and B6.IFN-γ0 mice (P < .0001). (B) Significant differences from the B6.pfp0 group were determined by a Mann-Whitney U test and denoted (*P < .0001). The number of mice per group is shown in parentheses.

NK- and NKT-cell–mediated control of experimental tumor metastasis by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities.

(A) B6, B6.pfp0, B6.RAG-10, B6.TNF0, B6.IFN-γ0, and B6.gldmice or B6 mice treated with anti-NK1.1 were inoculated subcutaneously between the shoulder blades with RM-1 tumor cells (2 × 106), and tumors were allowed to establish for 9 days. Subcutaneous tumors were then resected and a dose range of RM-1 cells (as indicated) injected through the tail vein. Mice were killed 14 days later, the lungs were removed and fixed, and colonies were counted and recorded as the mean number of colonies ± SE. A group of B6 mice was depleted of NK1.1+ cells in vivo by mAb treatment (100 μg/injection) on days −2, 0 (day of intravenous tumor inoculation), 2, and 9. (B) B6, B6.pfp0, B6.IFN-γ0, and B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0mice or B6 and B6.pfp0 mice treated with anti–mIFN-γ mAb (500 μg/injection) or control mAb (500 μg/injection) were treated as above. Mice received anti–IFN-γ mAb on days −2, 0 (day of intravenous tumor inoculation), 2, 7, and 10, with some groups receiving anti–mIFN-γ mAb early (days −2, 0) or late (days 7, 10). (A) Significant differences from the B6 group were determined by a Mann-Whitney U test (*P < .0001). Additionally, mice treated with anti-NK1.1 had significantly more metastases than any other group, including B6.pfp0 and B6.IFN-γ0 mice (P < .0001). (B) Significant differences from the B6.pfp0 group were determined by a Mann-Whitney U test and denoted (*P < .0001). The number of mice per group is shown in parentheses.

To evaluate whether the effector functions of pfp, IL-12, and IFN-γ were independent or overlapping, B6, B6.Jα2810, B6.IL-12p400, or B6.pfp0 mice were treated with neutralizing antimouse IFN-γ mAb over the course of the challenge with RM-1 tumor cells. Anti–IFN-γ mAb significantly increased the incidence of lung metastasis in both B6 and B6.pfp0 mice, but only minor increases were observed in B6.Jα2810 or B6.IL-12p400 mice (Figure 3B). The effect was most prominent when mAb was administered early, rather than late, after the tumor challenge. The enhanced number of RM-1 lung metastases in B6.pfp0 mice treated with anti–IFN-γ was further supported by the number of metastases in B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice. When directly compared (ie, same experiments), the B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0mice displayed tumor incidence equivalent to B6 mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells (Figure 3B compared with Figure 3A). NKT cells have recently been demonstrated to rapidly activate NK cells by their production of IFN-γ.25 The early protective effect of anti–IFN-γ mAb in the RM-1 tumor model may also support this concept. Nonetheless, the greater defect observed in mice depleted of all NK1.1+ cells suggested that NK cells have protective mechanisms independent of NKT cells. The results in mice deficient for pfp, or pfp and IFN-γ, indicated this independent antimetastatic function of NK cells may involve both the cytolytic activity of pfp and antitumor activity of IFN-γ. Therefore, these data in the RM-1 tumor model supported our previous results in the DA3 tumor model—that innate effector cells protected the host from lung metastases and that pfp and IFN-γ were independent effector mechanisms that contributed to protection.

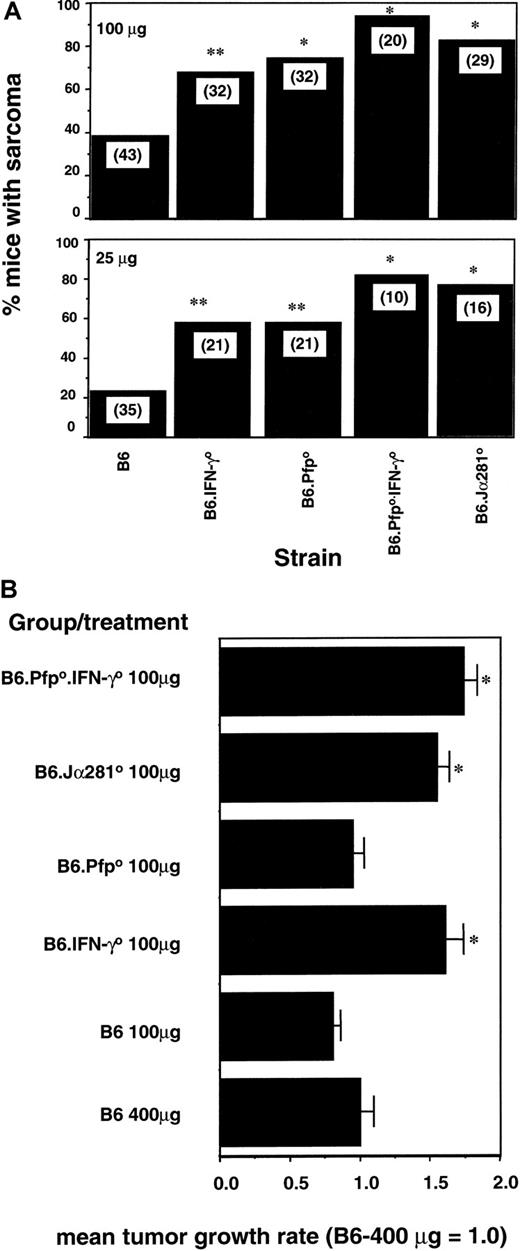

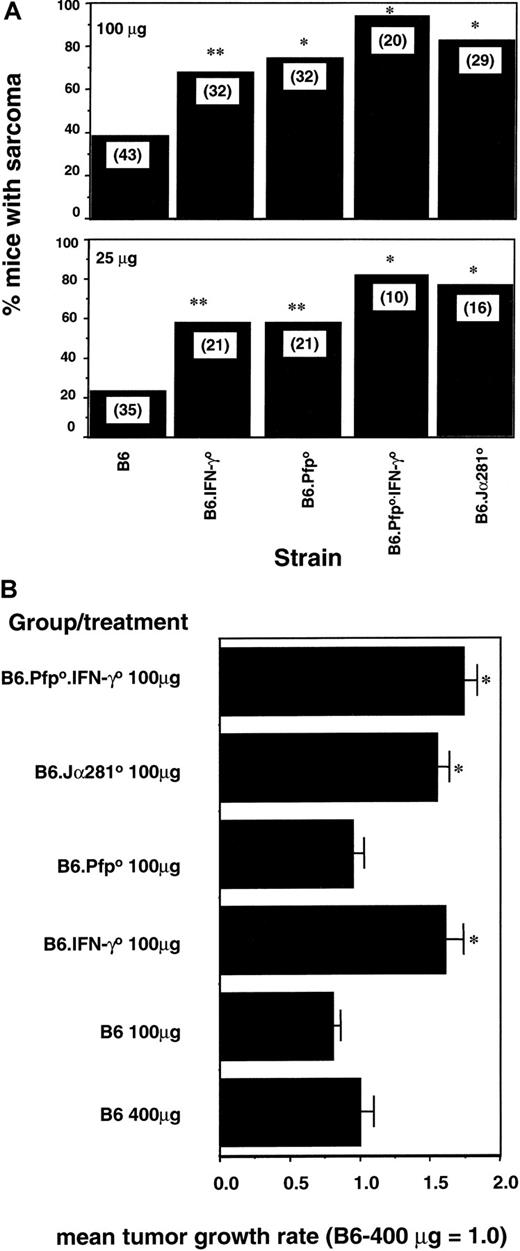

NKT-cell–mediated control of MCA-induced fibrosarcoma by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities

Induction of fibrosarcoma by MCA has previously been demonstrated to be controlled by effector cells in a pfp-dependent and an IFN-γ receptor–dependent manner.2,16,19 By examining the relative deficiencies of B6 mice depleted of NK1.1+ cells and B6 mice specifically deficient in Vα14 TCR NK1.1+ T cells (Jα2810), we have been able to establish that these NKT cells play a major role in protection from MCA-induced sarcoma.19 Herein we created B6 mice doubly deficient for pfp and IFN-γ. Groups of B6 and B6 gene–targeted mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 different doses of MCA, and fibrosarcoma development was monitored for 180 days (Figure4A). At the doses examined, B6.pfp0 mice and B6.IFN-γ0 mice developed tumors significantly more frequently than B6 control mice. These data in B6 mice confirmed a role for pfp6,8 and IFN-γ,16 previously suggested by studies in this strain. In addition, at the 2 doses examined, a greater proportion (90% and 80%) of B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice succumbed to MCA-induced sarcoma than either B6.pfp0 mice or B6.IFN-γ0 mice (Figure 4A). The B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice displayed a similar sarcoma incidence to NKT-cell–deficient B6.Jα2810 mice (Figure 4A). Thus, in a third model involving innate protection from tumor initiation, the combined deficiency of pfp and IFN-γ compromised the host to a greater extent than loss of pfp or IFN-γ alone. A random group of 10 mice was monitored for individual tumor growth in groups receiving 100 μg MCA (Figure 4B) or 25 μg MCA (data not shown). Strikingly, the growth of sarcomas in B6.IFN-γ0, B6.pfp0.IFN-γ0, or B6.Jα2810 mice was significantly greater than that compared with B6 or B6.pfp0 mice. This increase in the growth rate of sarcomas in IFN-γ–deficient mice occurred despite similar rates of incidence between B6.pfp0 and B6.IFN-γ0 mice (Figure 4A). Similar data have been obtained in the same BALB/c strains of mice treated with MCA (data not shown). Therefore, though IFN-γ was important in the control of sarcoma initiation, it appears that IFN-γ and NKT cells were also very important in the control of sarcoma growth.

NKT-cell–mediated control of MCA-induced fibrosarcoma by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities.

(A) Groups of 10 to 43 B6, B6.Jα2810, B6.pfp0, B6.IFN-γ0, or B6 pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice were injected subcutaneously in the hind flank with 100 μg or 25 μg MCA diluted in 0.1 mL corn oil. Mice were observed weekly for tumor development over the course of 50 to 180 days. Tumors larger than 4 mm in diameter and demonstrating progressive growth over 3 weeks were counted as positive. Groups with statistically higher incidence than B6 mice were noted (*P < .01; **P < .05; Fisher exact test). (B) Representative individual fibrosarcomas from groups of 10 mice (above) were compared with a group of B6 mice receiving 400 μg MCA. Tumor size was measured daily with a caliper square as the product of 2 diameters, and results were recorded as the tumor size (cm2). The mean growth rate of tumors was determined from the gradients of individual plots and was normalized against the mean of the B6 (400 μg) group = 1.0. Data are plotted as the mean ± SE, and significant differences to the B6 (400 μg) control were determined by an unpaired t test with Welch correction (*P < .01)

NKT-cell–mediated control of MCA-induced fibrosarcoma by independent pfp and IFN-γ activities.

(A) Groups of 10 to 43 B6, B6.Jα2810, B6.pfp0, B6.IFN-γ0, or B6 pfp0.IFN-γ0 mice were injected subcutaneously in the hind flank with 100 μg or 25 μg MCA diluted in 0.1 mL corn oil. Mice were observed weekly for tumor development over the course of 50 to 180 days. Tumors larger than 4 mm in diameter and demonstrating progressive growth over 3 weeks were counted as positive. Groups with statistically higher incidence than B6 mice were noted (*P < .01; **P < .05; Fisher exact test). (B) Representative individual fibrosarcomas from groups of 10 mice (above) were compared with a group of B6 mice receiving 400 μg MCA. Tumor size was measured daily with a caliper square as the product of 2 diameters, and results were recorded as the tumor size (cm2). The mean growth rate of tumors was determined from the gradients of individual plots and was normalized against the mean of the B6 (400 μg) group = 1.0. Data are plotted as the mean ± SE, and significant differences to the B6 (400 μg) control were determined by an unpaired t test with Welch correction (*P < .01)

Discussion

In 3 distinct models of tumor initiation and metastasis, the sensitivity of mice deficient in pfp and IFN-γ indicated that both effector mechanisms independently contribute to innate tumor immunity mediated by NK1.1+ NK or NK1.1+ T cells. For some time it has been recognized that IFN-γ production and pfp-mediated cytotoxicity may be distinct events that contribute to innate immunity. In particular, in viral infection, IL-12 is required for NK cell IFN-γ production but not cytotoxicity, whereas IFN-α/β production is dominant for enhanced NK lytic activity.26 In T-cell–mediated responses, a critical balance exists between direct cytotoxicity mediated by pfp and IFN-γ secretion that determines the outcome of viral infection and dictates immune homeostasis.27,28 In tumor models, each of pfp and IFN-γ have been demonstrated to contribute to the control of tumor incidence and metastasis,6-8,15,16,19,23,29 30 but no previous studies have directly compared their relative activities in the same model or examined the effect of removing both activities. Herein, in innate antitumor responses that involve relatively different contributions by NK and NKT cells, we have demonstrated for the first time that the killer cell pfp and cytokine IFN-γ constitute independent mechanisms that together control tumor initiation and metastasis.

The critical role of pfp in the direct cytolysis of tumor cells by NK cells is undisputed2; however, the mechanism(s) of IFN-γ action may be more diverse,12,31-36 and exactly which function is most important remains controversial. Although originally defined as an agent with direct antiviral activity,37 IFN-γ regulates several aspects of the immune response, including the stimulation of antigen presentation by up-regulation of major histocompatability complex (MHC) class I and II molecules,12 the orchestration of leukocyte–endothelium interactions,12,31 the effects on cell proliferation32 and sensitivity to apoptosis,33,34 the stimulation of the bactericidal activity of phagocytes,12 and anti-angiogenesis.35,36 A recent study has also indicated that IFN-γ may contribute directly to pfp-mediated apoptosis by altering target cell sensitivity.38 From this and many other studies, it is clear the roles of IFN-γ in host responses to tumor are complex, and it will not be easy to dissect the relative role of these molecules in destroying tumors, activating innate cells, or inhibiting tumor angiogenesis. Much of the reason for the controversies about which IFN-γ function is most important is the great variety of settings in which IFN-γ has been studied. We chose to focus on tumor models involving several different host innate responses, with the knowledge that each tumor may be controlled by a unique combination of NK/NKT cell mechanisms. Although our study has not contributed greatly to our knowledge of how IFN-γ may control tumors, in at least one model (DA3), the enhancement of tumor immunogenicity by IFN-γ up-regulation of MHC class I and II molecules seems unlikely given that T cells played no part in host protection from tumor metastasis.

One outstanding feature of tumor behavior in mice deficient for IFN-γ was the increased growth rate of MCA-induced sarcomas. The fact that NKT-cell–deficient mice, but not pfp-deficient mice, also demonstrated increased sarcoma growth further suggested that IFN-γ may be an important feature of the NKT-cell response. The effect of IFN-γ was distinct from that observed in a study comparing IFN-γ–responsive and –unresponsive mammary carcinomas that enlarged at similar rates.35 However, we (Smyth, unpublished data) and others15,29 have observed that IFN-γ is an important molecule in the control of tumor growth in other models. The mechanism by which IFN-γ controls sarcoma tumor growth remains unknown, but we did note that in vitro stimulation of cell lines derived from MCA-induced tumors with IFN-γ did not reveal any decrease in proliferation (data not shown). Additional combinations of cytokines may be required to determine whether any combination can suppress tumor cell proliferation. The possibility that IFN-γ has anti-angiogenic activity is also being explored; however, previous data using the MCA tumor model suggested that the key targets of the action of IFN-γ were the tumor cells themselves.16 IFN-γ may also have been controlling tumor growth in the RM-1 and DA3 metastasis models. Thus, in the absence of an assay to measure micrometastases for these experimental tumors, it is possible that numbers of surface lung tumor colonies measured at defined points in time may have underestimated tumor burden in wild-type and B6.pfp0 mice.

In summary, we have used the most rigorous and specific means available to distinguish the relative roles of NK and NKT cells in their control of tumor initiation, metastasis, and growth. Regardless of the varying relative roles of NK and NKT cells in each of the models used, host pfp and IFN-γ were consistently demonstrated to contribute independently to tumor control. Future efforts will focus on defining how pfp-independent NK/NKT-cell antitumor functions are orchestrated by IFN-γ.

Acknowledgment

We thank the staff of the ARI-BRL for their maintenance and care of the mice in this project.

Supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia project grant. M.J.S. is supported by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Mark J. Smyth, Cancer Immunology, Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute, Locked Bag 1, A'Beckett Street, Victoria, Australia, 8006; e-mail: m.smyth@pmci.unimelb.edu.au.