Abstract

Constitutively activated nuclear factor (NF)-κB is observed in a variety of neoplastic diseases and is a hallmark of the malignant Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells (H/RS) in Hodgkin lymphoma. Given the distinctive role of constitutive NF-κB for H/RS cell viability, NF-κB–dependent target genes were searched for by using adenoviral expression of the super-repressor IκBΔN. A surprisingly small but characteristic set of genes, including the cell-cycle regulatory protein cyclin D2, the antiapoptotic proteins Bfl-1/A1, c-IAP2, TRAF1, and Bcl-xL, and the cell surface receptors CD86 and CD40 were identified. Thus, constitutive NF-κB activity maintains expression of a network of genes, which are known for frequent, marker-like expression in primary or cultured H/RS cells. Intriguingly, CD40, which is able to activate CD86 or Bcl-xL via NF-κB, is itself transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB through a promoter proximal binding site. NF-κB inhibition resulted in massive spontaneous and p53-independent apoptosis, which could be rescued by ectopic expression of Bcl-xL, underscoring its dominant role in survival of H/RS cells. Hence, NF-κB controls a signaling network in H/RS cells, which promotes tumor cell growth and confers resistance to apoptosis.

Introduction

Nuclear factor (NF)-κB transcription factors regulate the expression of numerous genes that are necessary for proper functioning of the immune system and are key mediators of inflammatory responses to pathogens.1,2 Furthermore, NF-κB activity is associated with cell proliferation, transformation, and tumor development.3-5 One of its most important functions is the activation of an antiapoptotic gene expression program.6-8The NF-κB/Rel family consists of 5 members (p50, p52, p65 [RelA], c-Rel, and RelB), which can form various homodimeric or heterodimeric complexes. NF-κB is activated by the release from cytoplasmic IκB proteins and subsequently translocates into the nucleus.1,2,9 Activation is triggered by signal-induced phosphorylation of IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε at N-terminal serines, which target the inhibitors for rapid degradation by the proteasome.10-12 The IκB kinase (IKK) complex, containing 2 protein kinases, IKKα and IKKβ, is responsible for the inducible phosphorylation of IκBs and is the initial point of convergence for most stimuli that activate NF-κB.11 12

Evidence linking aberrant Rel/NF-κB activity to oncogenesis has emerged in recent years. Chromosomal rearrangements of genes coding for Rel/NF-κB factors have been observed in many human hematopoietic and solid tumors. Several human cancer cell types are characterized by persistent nuclear NF-κB activity, as a result of constitutive activation of upstream signaling kinases or mutations inactivating IκB subunits.5 Consistently, the viral oncoprotein v-Rel has transforming capacity in vitro and in vivo,13 and several oncogenic viruses, such as human T-cell leukemia virus type I and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), activate NF-κB as part of the transformation process.14 15

Recently, we have discovered deregulated NF-κB activation in Hodgkin disease (HD), a lymphoma characterized by a small fraction of mononuclear Hodgkin (H) and multinucleated Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells surrounded by a mixture of granulocytes, plasma cells, and T cells.16 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis suggested that H/RS cells from nodular sclerosis HD, the most common subtype, arise from germinal center B cells or from B cells at later stage of differentiation.17-20 The availability of several H/RS cell lines, mostly derived from pleural effusions, has allowed a detailed molecular analysis. In one case it could be demonstrated that the peripheral blood–derived cell line L1236 is clonally identical with H/RS cells in tissue sections of the patient.21

The molecular basis of constitutive NF-κB in H/RS is not completely understood. In some H/RS cell lines and in biopsy samples from patients with relapsed HD, mutations in the IκBα gene may contribute to constitutive NF-κB activation. These mutations produce nonfunctional or unstable IκBα proteins, missing various portions of the ankyrin domain and the C-terminal region.22-26 However, most HD cell lines and primary neoplastic cells lack mutations in theiκbα gene, and constitutive NF-κB activity could also be observed in cell lines with wild-type IκBα alleles.25 In all cases examined, IKKs were constitutively activated, resulting in rapid degradation of IκBα proteins and indicating ongoing signal transduction.25 Because HD is often associated with EBV, the EBV-encoded latent membrane protein-1 may activate NF-κB in these cases by promoting IκBα turnover.27 However, constitutive IKK activation was also observed in EBV− cell lines.25 Interestingly, H/RS cells strongly express CD30 and CD40, 2 members of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family that both can activate NF-κB.28-33

We previously analyzed the functional consequences of constitutive NF-κB activity by overexpression of the super-repressor IκBΔN in different H/RS cell lines.34 Inhibition of constitutive NF-κB led to decreased proliferation, enhanced apoptotic response upon growth factor withdrawal, and strongly impaired tumor growth in immunodeficient mice.34 These observations suggested an important role for NF-κB in the pathogenesis of HD and raise the question for target genes.

In the present study we performed a loss-of-function analysis to investigate potential NF-κB–dependent pathways in HD. Adenovirus-mediated expression of the super-repressor IκBΔN led to efficient NF-κB inhibition, which caused massive spontaneous apoptosis. A distinct network of new or previously described NF-κB target genes was identified, including the cell-cycle regulatory protein cyclin D2, the antiapoptotic proteins Bfl-1/A1, c-IAP2, TNF receptor–associated factor (TRAF)1, and Bcl-xL and the cell surface receptors CD40 and CD86. Interestingly, the identified target genes are known for highly abundant expression in most of the primary or cultured H/RS cells analyzed. These genes are part of interdependent signaling and survival pathways that allow the malignant cells to suppress apoptosis and to promote cell-cycle progression.

Materials and methods

Virus construction, preparation, and infection

Construction of E1-deleted recombinant adenovirus genomes was performed by homologous recombination in Escherichia coliBJ5183 using standard methods.35 Adenovirus type 5 (Ad5)-IκBΔN contains an N-terminal–deleted IκBα complementary DNA (cDNA) (amino acids 71 to 317 36) flanked by the RSV 3′LTR and the bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal. Ad5-control contains the transcriptional control units of the former virus but no coding sequence. Both virus genomes harbor the E3 deletion of pBHG10.37

Recombinant viruses were generated by transfection of linearized adenovirus genomes onto HEK293 cells.38 After plaque purification and 3 rounds of virus amplification in HEK293 cells, large purified virus stocks were produced as previously described.39 Virus titers were determined by end-point dilution assay, and the integrity of recombinant viruses was verified by restriction analysis of DNA isolated from purified virus stocks. Potential contamination of virus stocks with wild-type Ad5 was checked by a PCR-based method and was less than 10−8 in all virus preparations.

For adenoviral infection, 1 × 106 to 1 × 107 cells were pelleted and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium (supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum [FCS]) at a concentration of 1 × 107/mL. Viruses were added (multiplicity of infection [MOI] 300), and cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. After infection cells were again pelleted and resuspended at a concentration of 3 × 105/mL.

Cell culture

Reh, Nam, L428, L1236, KMH-2, and Jurkat cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. COS-7 and MCF-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate. Transient transfections into COS-7 cells were carried out with Lipofectin Plus Reagent (Gibco) following the manufacturer's protocols. Nam and L428 cells were transfected using electroporation. A total of 2 × 106 cells were pelleted and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium without supplements. Plasmids were added at a total of 30 μg, and probes were incubated for 10 minutes at room temperature. Electroporation was carried out with Gene-Pulser II (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) in a 0.4-cm cuvette with 960 μF and 0.18 kV. Subsequently, probes were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C and finally transferred to 10 mL RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. Namalwa cells were transfected with an IκBΔN expression construct36 or an empty vector, and stable clones were selected with G418 (Gibco).

DNA constructs

The pBluescript SK II+ vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) containing a 3.5-kilobase (kb) genomic clone of CD40 40was kindly donated by J. Watson (Genesis Research and Development Cooperation, Auckland, New Zealand). For generating CD40luc and different deletion mutants, the CD40 5′ flanking region was amplified by PCR and subcloned as a KpnI/HindIII fragment into pGL2 (Promega, Madison, WI). MκB3luc and −458MκBluc containing point mutations in the NF-κB3 site (GGGAAACTCC; mutations are underlined) were generated by Quick Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene). For pcDNAFlag-p65 and pcDNAFlag-p50, double-stranded oligonucleotides containing the Flag epitope sequence were cloned asHindIII/BamHI fragments into pCDNA3 (Invitrogen, Groningen, The Netherlands). Subsequently p50 (amino acids 1-377) and p65 cDNAs were amplified by PCR and cloned asBglII/XhoI (p50) or asBamHI/EcoRI (p65) fragments into pcDNA3Flag; p2κBluc was described previously41; and pCMVBcl-xL was donated by G. Cichon (Humboldt University, Berlin, Germany).

EMSA and Western blotting

Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described previously.42 After washing the cells with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), lysis buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 350 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonident P-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and a cocktail of protease and phosphatase inhibitors) was added, and after 10 minutes of incubation at 4°C the lysate was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 14 000 rpm in a microfuge. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as described previously.43 For Western blotting, 20 to 50 μg of extracted proteins was separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels. Gels were blotted onto nitrocellulose (Amersham) by a semidry method, and immune-detection was performed by chemiluminescence following the manufacturer's instructions (NEN Life Science Products). The primary antibodies used were mouse monoclonal antibodies against cyclin D1 (66271A), cyclin D2 (14821A), cyclin E (14591A), p53 (15791A) (all of BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany), TRAF1 (sc-6253, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against IκBα (C-21, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), CDK4 (H-22, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), c-IAP-2 (R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany), caspase-3 (65906E BD, Pharmingen), Bcl-xL (B22630, Transduction Laboratories, Heidelberg, Germany), and goat polyclonal antibody against Bfl-1/A1 (sc-6020, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antimouse, antirabbit (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), or antigoat antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used for secondary detection.

Northern blotting

Total RNA was prepared using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany); 20 μg aliquots of RNA were fractionated on a 1% agarose/6% formaldehyde gel transferred onto Hybond N membrane (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany) and cross-linked with an ultraviolet cross-linker. Blots were hybridized overnight with random-primed 32P-labeled probe at 65°C in Church buffer (7% SDS, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.5 M NaPO4, pH 7.2). For generation of probes, IMAGE (integrated molecular analysis of genomes and their expression) cDNA clones (Resource Center of the German Human Genome Project at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics) were digested, and isolated fragments were labeled with Megaprime DNA Labeling System (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). For CD40, clone p998L091052 was digested withPstI/HpaI, giving a 796–base pair fragment. For CD86, clone p998E184146 was digested with BstXI, giving a 368–base pair fragment. After hybridization, blots were washed twice in 2 × SSC (0.3 M NaCl, 0.03 M Na3 citrate, 0.1% SDS) for 15 minutes at room temperature and once in 0.2 × SSC–0.1% SDS for 15 minutes at 65°C.

Flow cytometry

Expression of surface antigens was examined by indirect immunofluorescence using flow cytometry (Epics XL-MCL flow cytometer, Coulter, Krefeld, Germany). Cells were washed once with PBS and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with antibodies against CD40 (33071A, BD Pharmingen) or CD86 (33401A, BD Pharmingen). Cells subsequently were washed twice with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC)–conjugated sheep antimouse antibody (515-095-00, Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Finally, cells were washed twice with PBS.

Apoptosis detection

For annexin staining 3 × 105 cells were pelleted, washed once with PBS, and incubated with annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide solution (Bender Med Systems, Vienna, Austria) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Flow cytometric analysis was performed using Epics XL-MCL flow cytometer (Coulter).

Large-scale nucleic acid array

Total RNA was prepared using guanidine isothiocyanate. RNA was analyzed using Atlas cDNA Array I (Clontech Laboratories. Palo Alto, CA). All subsequent steps were performed with Atlas Pure Total RNA Labeling System (Clontech Laboratories). Hybridization of the cDNA was performed according to the manual. Membranes were exposed to a phosphoro-imaging screen. Hybridization signals were quantified with Tina (Raytest Isotopenmessgeraete, Straubenhardt, Germany).

Results

Adenovirus-mediated IκBαΔN expression abrogates NF-κB activity and affects cell growth of L428 cells

Constitutive NF-κB activity has been recognized as a critical hallmark in the transformation process of H/RS cells.17 An important step in understanding the molecular function of NF-κB in these malignant cells is the identification of NF-κB–dependent target genes. For this purpose we have employed adenovirus-mediated expression of the super-repressor IκBΔN to down-modulate constitutive NF-κB activity. Adenoviral infection efficiency was tested in different H/RS cell lines using an adenovirus-expressing β-galactosidase. In L428 cells the infection efficiency was nearly 100%, whereas in other cell lines (L1236, KMH-2) a maximum of 30% to 40% was reached (MOI 300, data not shown).

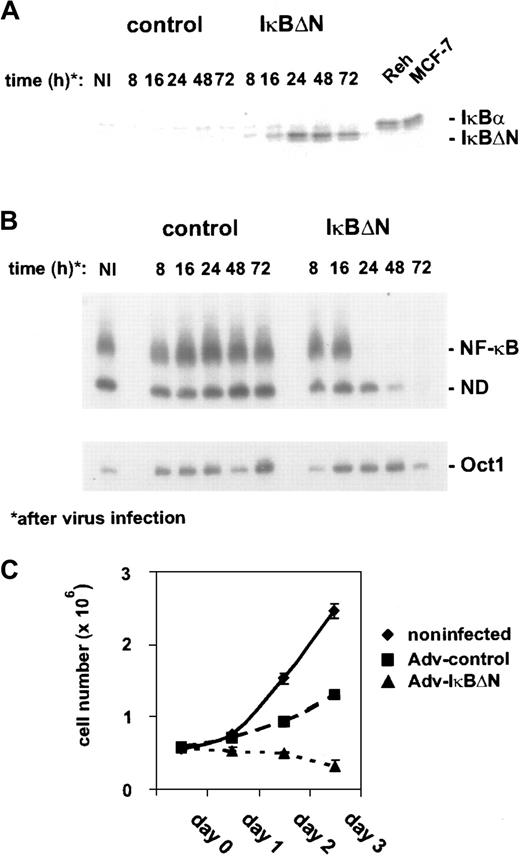

Thus, L428 cells were chosen for transfection with Ad5-IκBΔN or Ad5-control. IκBΔN was expressed 16 hours after infection and reached a maximum 8 hours later (Figure1A). The expression level of IκBΔN in L428 cells was comparable to that of endogenous IκBα in control cells (Figure 1A). However, L428 cells express a C-terminally truncated form of IκBα at a low level that cannot be detected by the antibody used.25 NF-κB DNA binding activity, analyzed by EMSA (Figure 1B), was nearly abolished 24 hours after infection with Ad5-IκBΔN but unchanged in Ad5-control–infected cells. In contrast, Oct1 binding activity, as a control, was not affected (Figure1B, lower panel). Because NF-κB could be very efficiently blocked within 24 hours, adenoviral-mediated expression of IκBΔN in L428 cells is an ideal approach to study NF-κB function.

Adenovirus-mediated IκBΔN expression abrogates NF-κB activity and affects growth of L428 cells.

(A) Expression of IκBΔN in L428 cells. L428 cells were infected with an adenovirus expressing IκBΔN or with a control adenovirus containing an empty expression cassette (Ad5-IκBΔN and Ad5-control; MOI 300). Whole-cell extracts of infected and control cells (MCF-7, Reh) were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-IκBα antibody. Note that L428 cells are defective in wild-type IκBα expression. (B) NF-κB binding activity. Whole-cell extracts of L428 cells infected with Ad5-control and Ad5-IκBΔN were analyzed by EMSA using H2K and H2B binding site probes for NF-κB (upper panel) and Oct-1 (lower panel), respectively. (C) Growth rate. Numbers of noninfected or infected L428 cells (as indicated) were determined for 3 days starting with 5 × 105 cells. Five independent experiments were performed. NI indicates noninfected; ND, not determined.

Adenovirus-mediated IκBΔN expression abrogates NF-κB activity and affects growth of L428 cells.

(A) Expression of IκBΔN in L428 cells. L428 cells were infected with an adenovirus expressing IκBΔN or with a control adenovirus containing an empty expression cassette (Ad5-IκBΔN and Ad5-control; MOI 300). Whole-cell extracts of infected and control cells (MCF-7, Reh) were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-IκBα antibody. Note that L428 cells are defective in wild-type IκBα expression. (B) NF-κB binding activity. Whole-cell extracts of L428 cells infected with Ad5-control and Ad5-IκBΔN were analyzed by EMSA using H2K and H2B binding site probes for NF-κB (upper panel) and Oct-1 (lower panel), respectively. (C) Growth rate. Numbers of noninfected or infected L428 cells (as indicated) were determined for 3 days starting with 5 × 105 cells. Five independent experiments were performed. NI indicates noninfected; ND, not determined.

First, we determined cell growth of noninfected and Ad5-control– or Ad5-IκBΔN–infected L428 cells (Figure 1C). Cells infected with Ad5-control showed an increase in cell number within 3 days after infection. However, compared with noninfected cells the growth rate was reduced, indicating that viral infection affected cell growth. NF-κB inhibition led to a decrease in cell number during the observed time course. However, it is difficult to dissect if this defect is due to inhibited proliferation, increased apoptosis, or both. Cell-cycle analysis revealed a strongly increased sub-G1 peak and decreased S- and G2/M populations (not shown), indicating enhanced apoptosis (see below) but not excluding simultaneously slowed cell-cycle progression.

NF-κB inhibition by adenoviral IκBΔN expression causes massive spontaneous apoptosis

In a previous study we showed that NF-κB inhibition by stable expression of IκBαΔN strongly promoted apoptosis of H/RS cells upon growth factor withdrawal.34 Because that analysis required the selection of stable cell clones with inhibited NF-κB activity, clones with compensatory deregulation of unknown endogenous genes may have been selected. Hence, it is important to analyze the apoptotic response of Ad5-IκBΔN–infected L428 cells. About 48 hours after infection, 66% of the cells were positive for annexin staining (Figure 2A). In contrast, only a few cells infected with Ad5-control were positive. Adv-IκBΔN–induced apoptosis was also observed in a Tunel assay (data not shown). Finally, we analyzed caspase-3, a major effector protein during apoptosis. The inactive proenzyme (32 kd) undergoes processing during apoptosis to produce the active form (18 kd), which subsequently catalyzes proteolysis. In full agreement with the previous data, the active form of caspase-3 was observed 48 hours after infection with Ad5-IκBΔN but not after infection with control virus (Figure 2B). In summary, rapid NF-κB inhibition by Adv-IκBΔN induces massive spontaneous apoptosis in L428 cells.

NF-κB inactivation causes massive spontaneous apoptosis.

(A) Annexin staining was performed with Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells at the indicated time points (see “Materials and methods”). (B) Caspase-3 expression. Whole-cell extracts of noninfected and infected L428 cells were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting. NI indicates noninfected.

NF-κB inactivation causes massive spontaneous apoptosis.

(A) Annexin staining was performed with Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells at the indicated time points (see “Materials and methods”). (B) Caspase-3 expression. Whole-cell extracts of noninfected and infected L428 cells were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting. NI indicates noninfected.

H/RS cells express high levels of cyclin D2 in an NF-κB–dependent manner

Recent data revealed a direct function of NF-κB in cell-cycle progression by promoting cyclin D1 expression.44,45Because constitutive NF-κB activity in H/RS cells (Figure3A) contributes to cell-cycle progression,34 the expression of cyclin D1 and other cell-cycle regulatory proteins was analyzed in different H/RS and control cell lines (Figure 3B and data not shown). However, neither cyclin D1 nor cyclin E was specifically deregulated in H/RS cells compared with other cell types, but we observed a characteristic high-level expression of cyclin D2 in all H/RS cells, correlating with constitutive NF-κB activity (Figure 3A,B). To examine NF-κB dependency, cyclin D2 expression was analyzed in Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected L428 cells. In control cells, cyclin D2 levels were increased 48 and 72 hours after infection (Figure 3C), consistent with ongoing proliferation (Figure 1C). In contrast, NF-κB inhibition was accompanied by loss of cyclin D2 induction (Figure 3C), which might at least in part explain the observed growth defect. However, the strong apoptotic response (Figure 2) after NF-κB inhibition renders further analysis more difficult.

Cyclin D2 expression is NF-κB dependent.

(A) NF-κB binding activity. Whole-cell extracts of H/RS cells and control cells were analyzed by EMSA using an H2K binding site probe for NF-κB. (B) Expression of cyclins in H/RS and control cells. Steady state levels of cyclin D1, cyclin D2, and cyclin E proteins were determined by Western blotting using specific antibodies, as indicated (see “Materials and methods”). (C) Cyclin D2 expression of Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected L428 cells. Whole-cell extracts of noninfected and infected L428 cells were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting with anticyclin D2 antibody (upper panel). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-CDK4 antibody (lower panel). NI indicates noninfected.

Cyclin D2 expression is NF-κB dependent.

(A) NF-κB binding activity. Whole-cell extracts of H/RS cells and control cells were analyzed by EMSA using an H2K binding site probe for NF-κB. (B) Expression of cyclins in H/RS and control cells. Steady state levels of cyclin D1, cyclin D2, and cyclin E proteins were determined by Western blotting using specific antibodies, as indicated (see “Materials and methods”). (C) Cyclin D2 expression of Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected L428 cells. Whole-cell extracts of noninfected and infected L428 cells were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting with anticyclin D2 antibody (upper panel). The blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-CDK4 antibody (lower panel). NI indicates noninfected.

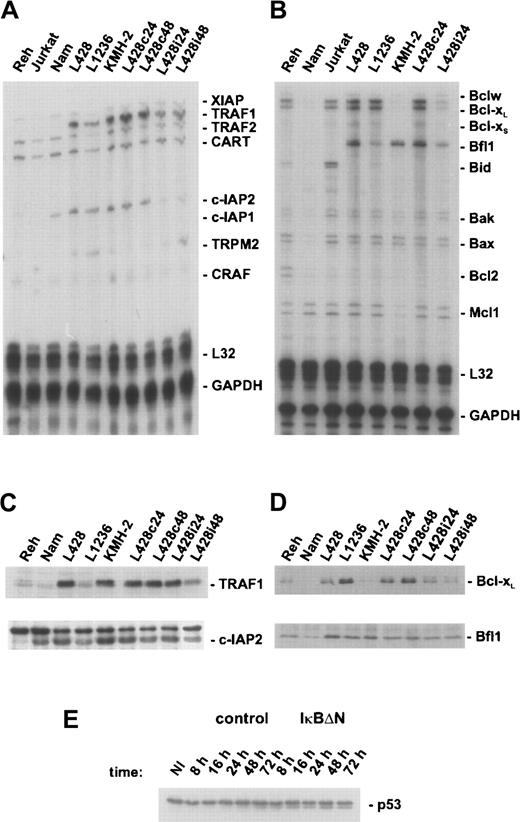

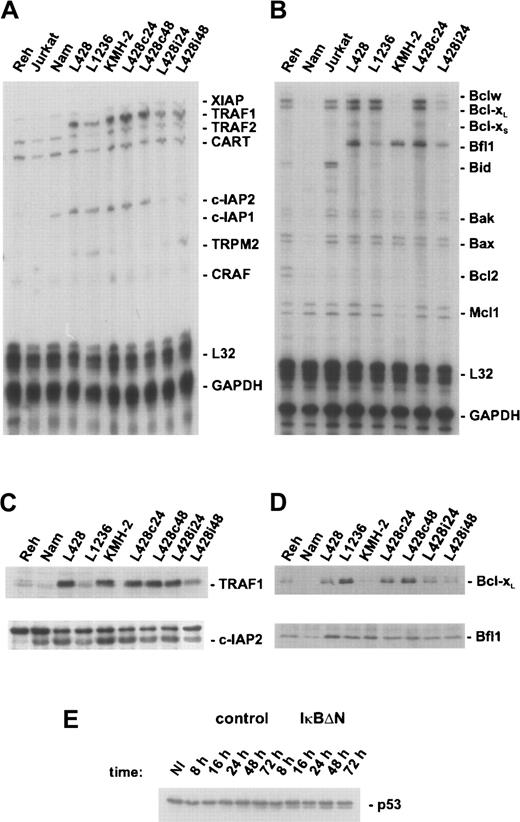

NF-κB controls expression of a distinct set of antiapoptotic genes

Because NF-κB inhibition caused massive spontaneous apoptosis in L428 cells (Figure 2), expression of genes with proapoptotic or antiapoptotic functions was analyzed with ribonuclease protection assays (Figure 4A,B). NF-κB inhibition did not affect expression of proteins that are known to accelerate apoptosis, like Bak or Bax. However, NF-κB inhibition caused a significant decline of expression of several antiapoptotic genes that were found highly expressed in H/RS cells compared with control cells. In particular, TRAF1 overexpression was observed in L428 and KMH-2 cells and to a minor extent in L1236 cells (Figure 4A, upper panel of 4C). Because TRAF1 overexpression in transgenic mice inhibits antigen-induced apoptosis in CD8+ T lymphocytes,47 TRAF1 might be involved in the regulation of apoptosis in reactive lymphoid cells and their neoplastic counterparts.

NF-κB regulates expression of a distinct set of antiapoptotic genes in H/RS cells.

(A) L428 cells were infected with Ad5-control or Ad5-IκBΔN, respectively, and total RNA was prepared 24 hours (L428c24, L428i24) or 48 hours (L428c48, L428i48) after infection. Additionally, RNA was prepared from different control and H/RS cells. The ribonuclease protection assay was performed according to the supplier's instructions (BD Pharmingen). Human apoptosis template set hAPO-5 was labeled with α-32P UTP. A total of 10 μg RNA and 8 × 105 cpm of labeled probes were used for hybridization. (B) Ribonuclease protection assay using human apoptosis template set hAPO-2b was performed as described in panel A. A total of 10 μg RNA and 3 × 106 cpm of labeled probes were used for hybridization. (C) Whole-cell extracts of different control and H/RS cells or infected L428 cells (as indicated) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-TRAF1 (upper panel) or anti–c-IAP2 (lower panel) antibodies. (D) Whole-cell extracts, as in panel C, were analyzed in Western blots for Bcl-xL (upper panel) or Bfl-1/A1 (lower panel). (E) Expression of p53. Whole-cell extracts of noninfected and infected L428 cells were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-p53 antibody. NI indicates noninfected.

NF-κB regulates expression of a distinct set of antiapoptotic genes in H/RS cells.

(A) L428 cells were infected with Ad5-control or Ad5-IκBΔN, respectively, and total RNA was prepared 24 hours (L428c24, L428i24) or 48 hours (L428c48, L428i48) after infection. Additionally, RNA was prepared from different control and H/RS cells. The ribonuclease protection assay was performed according to the supplier's instructions (BD Pharmingen). Human apoptosis template set hAPO-5 was labeled with α-32P UTP. A total of 10 μg RNA and 8 × 105 cpm of labeled probes were used for hybridization. (B) Ribonuclease protection assay using human apoptosis template set hAPO-2b was performed as described in panel A. A total of 10 μg RNA and 3 × 106 cpm of labeled probes were used for hybridization. (C) Whole-cell extracts of different control and H/RS cells or infected L428 cells (as indicated) were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-TRAF1 (upper panel) or anti–c-IAP2 (lower panel) antibodies. (D) Whole-cell extracts, as in panel C, were analyzed in Western blots for Bcl-xL (upper panel) or Bfl-1/A1 (lower panel). (E) Expression of p53. Whole-cell extracts of noninfected and infected L428 cells were prepared at the indicated time points and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-p53 antibody. NI indicates noninfected.

NF-κB inhibition caused a strong reduction of TRAF1 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels 24 hours after infection with Ad5-IκBΔN followed by reduced protein expression 48 hours after infection (Figure 4A, upper panel of 4C). A remarkably high and NF-κB–dependent mRNA expression was detected for both c-IAP2 and Bfl-1/A1 (Figure 4A,B). Consistent with the mRNA levels, H/RS cells exhibited a significantly higher Bfl-1/A1 protein expression than non-H/RS cells (Figure 4D, lower panel). The c-IAP2 protein expression was also elevated in H/RS cells (Figure 4C, lower panel). In L428 cells expressing IκBΔN, protein levels of both Bfl1-1/A1 and c-IAP2 were only slightly reduced, perhaps due to a longer half-life of these proteins. Finally, we found significantly higher Bcl-xL expression in L428 and L1236 cells compared with control cells (Figure 4B, upper panel of 4D). Loss of NF-κB activity in L428 cells had already caused a strong reduction of the protein level 24 hours after infection with Ad5-IκBΔN; 48 hours after infection Bcl-xL expression was nearly eliminated.

Furthermore, we analyzed expression of p53, a central regulator during apoptotic responses (Figure 4E). However, no change in steady state protein levels upon viral infection was observed, indicating p53-independent apoptosis. Taken together, constitutive NF-κB blocks apoptosis in RS cells by activating a distinct set of antiapoptotic genes that affect caspase-3 activation.

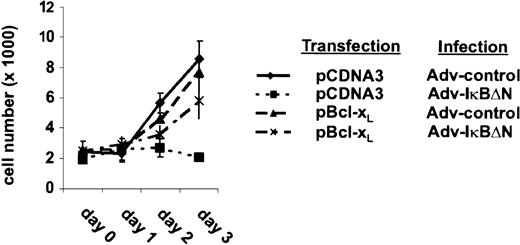

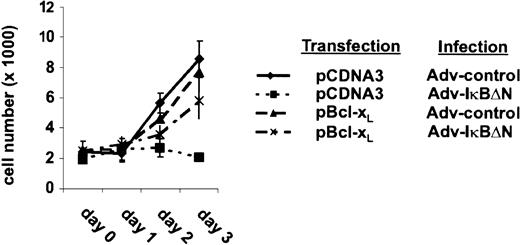

Ectopic expression of Bcl-xL rescues viability in H/RS cells lacking constitutive NF-κB activity

The strong NF-κB dependency of Bcl-xL expression indicates a predominant role of Bcl-xL in the survival of H/RS cells. To assess this hypothesis, L428 cells were transfected with a vector containing a Bcl-xL cDNA or an empty expression cassette. Transfected cells were monitored by cotransfecting a green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression vector. One day after transfection, cells were divided, infected with Ad5-control or Ad5-IκBΔN, and cell growth was determined (Figure5). Cells infected with Ad5-control showed in both cases an increase in cell number during the observed time course. In control-transfected cells, NF-κB inhibition caused a decrease in cell number within 3 days after infection, as observed in prior experiments (Figure 1C). In contrast, ectopic expression of Bcl-xL restored viability in cells lacking NF-κB activity. However, the increase in cell number was reduced compared with control cells. Thus, these observations demonstrate that Bcl-xL is one of the most critical antiapoptotic genes controlled by NF-κB in L428 cells.

Ectopic expression of Bcl-xL rescues survival of Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells.

L428 cells were transfected with 20 μg pCMVBcl-xL or pCDNA3, respectively, and 20 μg pEGFPN3 (Clontech Laboratories). One day after transfection (day 0) cells were divided and infected with Ad5-control or Ad5-IκBΔN. GFP-expressing cells were counted. Three independent experiments were performed.

Ectopic expression of Bcl-xL rescues survival of Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells.

L428 cells were transfected with 20 μg pCMVBcl-xL or pCDNA3, respectively, and 20 μg pEGFPN3 (Clontech Laboratories). One day after transfection (day 0) cells were divided and infected with Ad5-control or Ad5-IκBΔN. GFP-expressing cells were counted. Three independent experiments were performed.

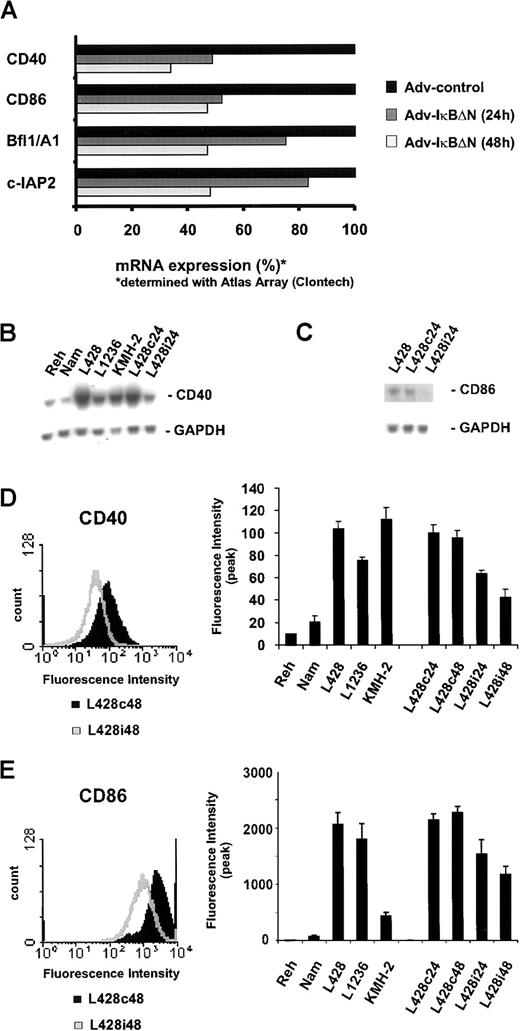

CD40 and CD86 are NF-κB–dependent target genes in H/RS cells

In an attempt to further clarify the function of NF-κB as a survival factor in H/RS cells, we searched for NF-κB–dependent target genes by probing a large-scale nucleic acid array with RNA from Ad5-control– or Ad5-IκBΔN–infected L428 cells. Again, Bfl-1/A1 and c-IAP2 could be identified as NF-κB–dependent target genes (Figure 6A), confirming our previous findings (Figure 4). Furthermore, NF-κB inhibition caused significantly reduced mRNA levels of the cell surface proteins CD40 and CD86 (Figure 6A). Surprisingly, no more candidates could be determined consistently, although the array contains several other genes previously assumed to be under control of NF-κB (eg, TNF-α, interleukin-6, TRAF2, and others; data not shown).

CD40 and CD86 are NF-κB–dependent target genes.

(A) L428 cells were infected with Ad5-control and Ad5-IκBΔN. RNA was analyzed using Atlas cDNA Array I (Clontech Laboratories). The figure shows a graphic representation of mRNA expression ratios between Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells. (B,C) Total RNA was extracted 24 hours after infection from L428 cells, infected with Ad5-control (L428c24) or Ad5-IκBΔN (L428i24), and from different control and H/RS cell lines. Northern blots were probed with32P-labeled CD40 or CD86 cDNA probes. As a control, the stripped blot was reprobed with a 32P-labeled GAPDH cDNA probe. (D,E) Flow cytometric analysis of surface CD40 or CD86 expression on L428 cells 48 hours after infection with Ad5-control (L428c48) and Ad5-IκBΔN (L428i48) (left panels). Flow cytometric analysis of surface CD40 or CD86 expression on control, various H/RS, and infected L428 cells. The graph represents peak fluorescence intensities of the indicated cell lines (right panels).

CD40 and CD86 are NF-κB–dependent target genes.

(A) L428 cells were infected with Ad5-control and Ad5-IκBΔN. RNA was analyzed using Atlas cDNA Array I (Clontech Laboratories). The figure shows a graphic representation of mRNA expression ratios between Ad5-control– and Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells. (B,C) Total RNA was extracted 24 hours after infection from L428 cells, infected with Ad5-control (L428c24) or Ad5-IκBΔN (L428i24), and from different control and H/RS cell lines. Northern blots were probed with32P-labeled CD40 or CD86 cDNA probes. As a control, the stripped blot was reprobed with a 32P-labeled GAPDH cDNA probe. (D,E) Flow cytometric analysis of surface CD40 or CD86 expression on L428 cells 48 hours after infection with Ad5-control (L428c48) and Ad5-IκBΔN (L428i48) (left panels). Flow cytometric analysis of surface CD40 or CD86 expression on control, various H/RS, and infected L428 cells. The graph represents peak fluorescence intensities of the indicated cell lines (right panels).

To confirm these findings, we analyzed CD40 and CD86 mRNA expression in L428 cells infected with Ad5-IκBΔN or Ad5-control and in different control and H/RS cells (Figure 6B,C). In agreement with previous data,30 32 CD40 mRNA was highly overexpressed in all H/RS cells tested, compared with Reh or Namalwa cells. NF-κB inhibition caused a significant reduction of CD40 and CD86 mRNA. Cell surface expression of both proteins was determined using flow cytometry. Specific fluorescence intensity of CD40 and CD86 staining in H/RS cells was strikingly higher than in control cells (Figure 6D,E, right panels). Infection of L428 cells with Ad5-IκBΔN led to a reduction of both CD40 (Figure 6D) and CD86 expression (Figure 6E). Hence, high expression of CD40 and CD86, typical for RS cells, is dependent on constitutive NF-κB.

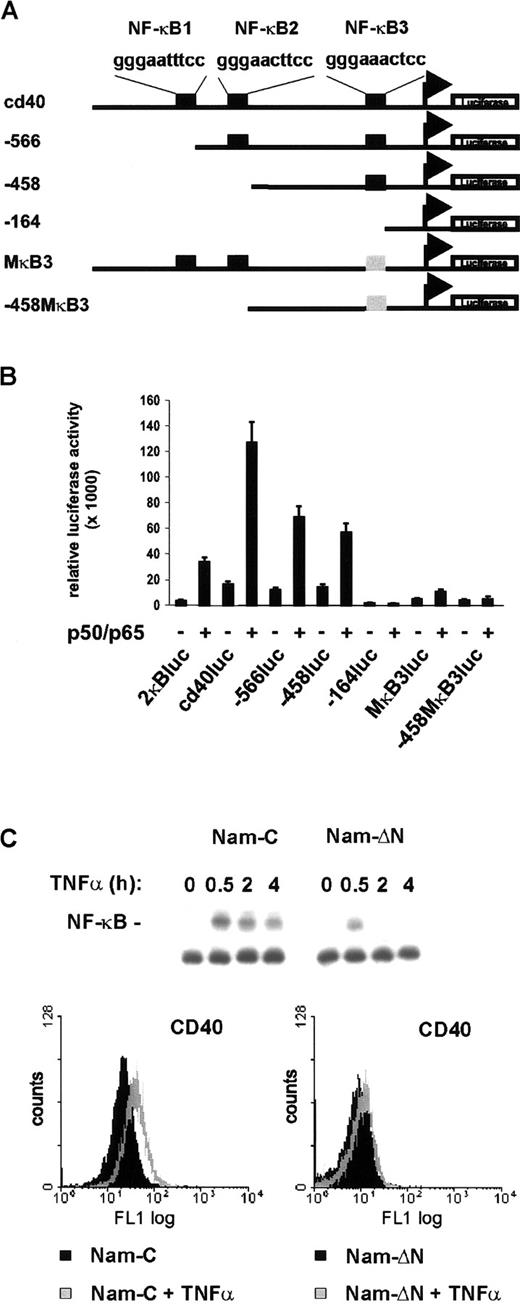

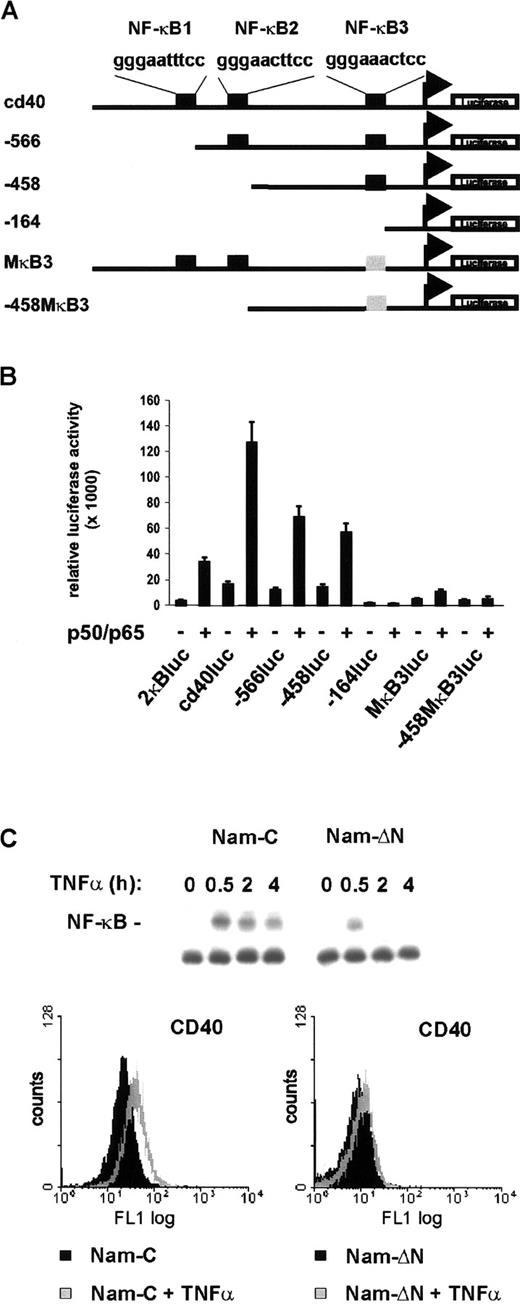

It is an intriguing finding that CD40, known to activate NF-κB as a downstream target, is itself under NF-κB control. To investigate if NF-κB directly activates CD40 transcription, 0.8 kb of the CD40 promoter 5′ flanking region40 was cloned in front of a luciferase reporter gene (Figure 7A). The upstream region contains 3 potential NF-κB binding sites. Coexpression of p50 and p65 in fact led to an 8-fold stimulation of the reporter gene (Figure 7B). The requirement of the NF-κB binding sites was examined with mutant constructs harboring successive 5′ deletions or point mutations (Figure 7A). Deletion of the sites NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 (−566luc, −458luc) interfered only moderately with NF-κB activation. In contrast, deletion or point mutation of NF-κB3 (−164luc, MκB3luc, −458MκB3luc) nearly abrogated NF-κB–dependent reporter gene activation (Figure 7B). Finally, to analyze whether activation of NF-κB also induces CD40 expression in non-Hodgkin cells, mock- and IκBαΔN-transfected Namalwa cells were treated with TNF-α. In control cells TNF-α strongly induced NF-κB DNA binding activity and significantly increased CD40 surface expression (Figure 7C, upper and lower left panels). In contrast, expression of the super-repressor IκBαΔN nearly abrogated both TNF-α–induced NF-κB activation and CD40 expression (Figure 7C, upper and lower right panels). Thus, CD40 is under transcriptional control of NF-κB and is activated primarily through the promoter-proximal binding site, NF-κB3.

Transcriptional regulation of the CD40 gene by NF-κB.

(A) Schematic map of the CD40 promoter and mutant constructs. Consensus NF-κB binding sites are designated NF-κB1, NF-κB2, and NF-κB3. Mutant NF-κB3 is shown in gray. The transcriptional start site is indicated corresponding to the previously published mRNA sequence.46 (B) Reporter gene activation. COS-7 cells were transfected with 200 ng of the different reporter constructs and 200 ng of p50/p65 expression constructs or pCDNA3 to give a total of 400 ng; 100 ng pRL-TK was cotransfected in each reaction. Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). (C) TNF-α stimulates CD40 expression via NF-κB. Control and IκBΔN–transfected Namalwa cells were treated with TNF-α (25 ng/mL). NF-κB DNA binding activity in whole-cell extracts was determined by EMSA (upper panel). Flow cytometric analysis of surface CD40 expression. Cells were either untreated or treated for 20 hours with TNF-α (lower panels).

Transcriptional regulation of the CD40 gene by NF-κB.

(A) Schematic map of the CD40 promoter and mutant constructs. Consensus NF-κB binding sites are designated NF-κB1, NF-κB2, and NF-κB3. Mutant NF-κB3 is shown in gray. The transcriptional start site is indicated corresponding to the previously published mRNA sequence.46 (B) Reporter gene activation. COS-7 cells were transfected with 200 ng of the different reporter constructs and 200 ng of p50/p65 expression constructs or pCDNA3 to give a total of 400 ng; 100 ng pRL-TK was cotransfected in each reaction. Luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). (C) TNF-α stimulates CD40 expression via NF-κB. Control and IκBΔN–transfected Namalwa cells were treated with TNF-α (25 ng/mL). NF-κB DNA binding activity in whole-cell extracts was determined by EMSA (upper panel). Flow cytometric analysis of surface CD40 expression. Cells were either untreated or treated for 20 hours with TNF-α (lower panels).

Discussion

High-level constitutive nuclear NF-κB is a characteristic property of the malignant cells of HD and is found in all established cell lines and in most H/RS cells in lymph node sections.16,17 34 In the H/RS cell line L428, constitutive NF-κB activity could be almost completely abrogated by adenoviral expression of the super-repressor IκBΔN. This approach enabled us to investigate the function of constitutive NF-κB in HD in more detail. The present study provides strong evidence that NF-κB transcriptionally regulates a network of genes that are important for the pathogenesis of HD.

NF-κB inhibition strongly affected growth of L428 cells (Figure 1C). Because NF-κB is known to promote cell-cycle progression in H/RS cells and affects the retinoblastoma protein checkpoint by transcriptional activation of cyclin D1 in fibroblasts,34,44,45 we analyzed expression of several cell-cycle regulatory proteins (Figure 3A and data not shown). In agreement with a recent publication,48 we observed a specific up-regulation of cyclin D2 in H/RS cells (Figure 3B). In contrast, as known for cells of hematopoietic origin, cyclin D1 was not strongly expressed. D-type cyclins are induced as part of the delayed early response to mitogenic stimulation, form active holoenzymes with CDK4 and CDK6, and promote G1-to-S phase transition by phosphorylating the retinoblastoma protein.49,50Overexpression of D-type cyclins reduces the dependency on exogenous growth factors and deregulates restriction point control, which is associated with malignant transformation.51 It is thus tempting to speculate that elevation of cyclin D2 levels in H/RS cells is part of the malignant transformation of these cells. NF-κB inhibition in L428 cells in fact caused a reduction of cyclin D2 protein expression (Figure 3C). Because induction of D-type cyclins is tightly regulated in early to mid G1 phase, a more detailed analysis is necessary to investigate NF-κB–dependent regulation of cyclin D2. The present experimental setting excludes addressing cyclin D2 function, because NF-κB inhibition in L428 cells induced spontaneous apoptosis and disrupted cell-cycle progression (Figure 2 and data not shown). Interestingly, the human cyclin D2 promoter contains 2 NF-κB binding sites.52 Furthermore, infection of resting B cells with EBV led to NF-κB activation and induction of cyclin D2.53 Taken together, these data suggest cyclin D2 as a potential NF-κB–dependent target gene. NF-κB–dependent up-regulation of cyclin D2 in H/RS cells might promote cell growth and tumorigenesis. Further experiments will be necessary to prove this hypothesis.

In diverse cell types, Rel/NF-κB transcription factors have been shown to inhibit apoptosis.8 NF-κB inhibition in H/RS cells by stably transfected IκBΔN caused enhanced apoptosis but only when cells were exposed to stress situations, such as growth factor deprivation.34 We could now demonstrate that adenovirus-mediated expression of the super-repressor IκBΔN caused massive spontaneous apoptosis, not requiring additional proapoptotic conditions (Figure 2A). Several reasons may account for the observed difference: the previous study employed stably transfected cells, and the selection procedure may have resulted in stable clones carrying compensatory deregulation of unknown cellular genes. Furthermore, spontaneous cell death induction may be caused by the viral infection stress, including the expression of viral proteins.54 It is also possible that the almost complete suppression of constitutive NF-κB by virally expressed IκBαΔN results in a much higher sensitivity of the cells. Our study clearly indicates that one or more death pathways are activated in H/RS cells. As a molecular effector of these pathways, activated caspase-3 was detected 48 hours after infection with the IκBαΔN virus (Figure 2 B). Several reports have demonstrated that the tumor suppressor p53 accumulates and directs apoptosis under appropriate physiologic conditions.55However, p53 levels were not changed upon adenoviral infection (Figure4E). Likewise, expression of p53 target genes p21 and Bax was not affected (Figure 4B and data not shown). Thus, apoptosis observed upon NF-κB inhibition was p53 independent. Furthermore, previously described transcriptional regulation of p53 by NF-κB was not observed in H/RS cells.56

During the last few years, a series of NF-κB candidate target genes involved in antiapoptotic responses have been described.8 In H/RS cells 4 antiapoptotic proteins, Bfl-1/A1, c-IAP1, TRAF1, and Bcl-xL were up-regulated by constitutive NF-κB. These findings are in agreement with recent reports that established transcriptional regulation of c-IAP2, Bfl-1/A1, and Bcl-xL by NF-κB.57-60Interestingly, Bcl-xL expression is NF-κB independent in EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cells,61 indicating a more complex regulation of the gene.

In contrast, several other potential NF-κB target genes, like TRAF2, c-IAP1, XIAP, or manganese superoxide dismutase, were not affected by NF-κB down-regulation in H/RS cells either in the large-scale nucleic acid array (data not shown) or in a ribonuclease protection assay (Figure 4A,C). Thus, the high-level constitutive NF-κB activity alone is not sufficient for activation of these genes. Interestingly, all NF-κB–dependent antiapoptotic genes we have identified are highly expressed in cultured H/RS cells (this study has found) or have been found to be expressed at high level and frequency in primary H/RS cells.62-65 Hence, the induction of a distinct set of antiapoptotic proteins that protect H/RS cells from cell death appears to be a central function of constitutive NF-κB activity in HD.

NF-κB–dependent regulation of Bcl-xL, a member of the Bcl-2 family,66 seems to have a predominant role in controlling survival of H/RS cells. Loss of constitutive NF-κB caused a fast and robust reduction of Bcl-xL protein amounts. Importantly, ectopic expression of Bcl-xL alone could restore viability in Ad5-IκBΔN–infected cells. Because Bcl-xL inhibits cytochrome C release from mitochondria,67 our data suggest that NF-κB inhibition leads to activation of the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9/caspase-3 cascade, which finally induces cell death. In agreement with this conclusion, caspase-3 was activated upon NF-κB inactivation. Down-regulation of the other antiapoptotic genes might further accelerate this pathway.

It has been suggested that NF-κB participates in the transcriptional control of more than 150 target genes.68 Although the large-scale nucleic acid array contains cDNA fragments for 30 of these described genes, only a few could be identified as NF-κB–regulated in H/RS cells. Besides the antiapoptotic proteins Bfl-1/A1 and c-IAP2, we detected the cell surface receptors CD86 and CD40 as NF-κB–dependent target genes. Analysis of mRNA and protein levels confirmed NF-κB–dependent expression. Thus, constitutive NF-κB activity does not cause a widely spread perturbation of gene expression in H/RS cells but selectively regulates a distinct subset of genes. The observation that several genes known to be regulated by NF-κB were not affected by blocking NF-κB with the super-repressor indicates a more complex regulation of these genes. At least in some cases, low RNA expression impeded a detailed analysis (data not shown). Of note, we assume that the number of NF-κB target genes in RS cells will still increase when screening of a larger number of genes is completed.

CD86 is a type 1 membrane glycoprotein expressed on antigen-presenting cells. Binding to the T-cell homodimers CD28 and CTLA-4 (CD152) generates costimulatory and inhibitory signals in T cells, respectively.69 NF-κB–dependent transcriptional regulation of the CD86 promoter has been demonstrated previously.70 Consistent with previous reports on CD86 expression on malignant cells in lymph node sections,71 72CD86 was strongly overexpressed in all H/RS cell lines tested.

We identified CD40 as a new NF-κB–regulated gene that is transcriptionally activated primarily through a promoter proximal binding site. CD40, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, is a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on antigen-presenting cells and on a variety of nonimmune cells. Receptor-mediated CD40 signaling is initiated by binding of CD40 ligand to the receptor. Extensive studies indicate that CD40 plays a critical role in activation, proliferation, differentiation, and antiapoptotic responses of B cells.73-78 Engagement of CD40 induces various transcription factors, including NF-κB, AP-1, nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), and signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)-3 and STAT-6.73,79 A variety of genes, including Bcl-xL, Bfl-1/A1, TRAF1, cIAP1, and CD86, are regulated upon CD40 signaling.60,75,80 81 In the present study, all of these genes were identified as NF-κB–dependent targets, demonstrating that NF-κB is the central effector of CD40 signaling for these genes.

The intriguing observation that CD40 itself is an NF-κB–dependent target gene suggests a regulatory loop between NF-κB and CD40, which is defective in HD. Indeed, high CD40 expression was observed in primary and cultured H/RS cells (Figure 6D).30,32 Prior studies indicate that CD40 overexpression may be sufficient to activate NF-κB.82 In H/RS cells, CD40 expression may have reached a critical threshold level that could result in ligand-independent CD40 engagement and ongoing signal transduction. In particular, this could perhaps explain the recently observed aberrant IKK activity in H/RS cells.25 Aberrant IKK activation might cause constitutive NF-κB activity in H/RS cells, which is further increased by mutations in the IκB molecules. In turn, constitutive NF-κB activity maintains a high level of CD40 expression. In patients, both high surface density of CD40 on H/RS cells and engagement by CD40 ligand by surrounding T cells might contribute to the constitutive NF-κB activity seen in H/RS cells in lymph node sections. Further studies will have to prove this hypothesis.

In summary, this study underlines a fundamental importance of NF-κB in HD. NF-κB controls a distinct network of genes that are important for proliferation, tumor development, and survival. Our findings might help to explain how constitutive NF-κB activity results in tumorigenesis and suggest that pharmacologic manipulation of the NF-κB system might have a therapeutic potential in HD.

We thank Vigo Heissmeyer for critical discussion and Erika Scharschmidt, Karin Gansel, and Ulrike Schneeweis for excellent technical assistance.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Claus Scheidereit, Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Robert-Rössle-Str 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: scheidereit@mdc-berlin.de.