Clinical observations show that older patients do not tolerate high-dose chemoradiotherapy as well as younger patients. It is unclear whether this is due to age-related differences in their responses to hematopoietic injury or to differential toxicities to other organs. In the present study, 6 young (0.5 years) and 6 elderly (8 years) dogs were challenged with 7 repeated nonlethal doses of 50 or 100 cGy total body irradiation (TBI) each (total 550 cGy), and 21 days of recombinant canine granulocyte–colony stimulating factor (rcG-CSF) after the last TBI dose. Recoveries of absolute neutrophil, platelet, and lymphocyte counts after each TBI dose, responses to rcG-CSF treatment, and telomere lengths in neutrophils were compared before and after the study. No differences were found in recoveries of neutrophils, platelets, or in responses to rcG-CSF among young and old dogs. In contrast, recoveries were suggestively worse in younger dogs. After rcG-CSF, platelet recoveries were poor in both groups compared with previous platelet recoveries (P < .01). Consequently, 2 old and 3 young dogs were euthanized because of persistent thrombocytopenia and bleeding. At the study's completion, marrow cellularities and peripheral blood counts of the remaining young and elderly dogs were equivalent. The telomere lengths in both groups were significantly reduced after the study versus beforehand (P = .03), but the median attritions of telomeres were not different. It was concluded that aging does not appear to affect hematopoietic cell recoveries after repeated low-dose TBI, suggesting that poor tolerance of radiochemotherapy regimens in older patients may be due to nonhematopoietic organ toxicities rather than age-related changes in hematopoietic stem cells reserves.

Introduction

Human and mammalian hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are able to maintain steady-state hematopoiesis throughout the life spans of individual members of each species. It is estimated that the proliferative capacities of HSCs greatly exceed those required during life.1,2 In serial transplantation studies in W/Wv-anemic recipient mice, HSC from healthy C57BL/6 (B6) donors generated normal hematopoiesis for at least 100 months, which is 3 to 4 times the life span of normal mice.3,4 In human recipients of allogeneic marrow grafts studied 20 to 30 years after transplantation, it was found that the hematopoiesis derived from the initial small HSC inoculum could sustain normal peripheral blood counts. Moreover, donor-derived hematopoiesis remained polyclonal, with only modest (0.94 kilobase [kb]) telomere shortening when compared with the hematopoiesis present in the original marrow donors.5 These findings were consistent with the notion that HSCs did not age significantly within the context of a normal life. However, current models of somatic cell replication impose an intrinsic timetable, known as cellular “replicative senescence,” which ultimately limits the number of cell divisions leading to reduced or exhausted ability to replicate.6,7 The “intrinsic timetable” is attributed to the progressive loss of telomere length during cell divisions.8 Telomere length has been correlated with replicative life span in various somatic cells, including HSCs, and has been observed to decrease with age.9,10 In these models, HSCs have a finite number of divisions. Therefore, repeated supra-normal challenges to an HSC pool have the potential to exhaust the system, which might result in marrow failure. These models also imply that HSCs from old donors should have a decreased proliferative potential in comparison with HSCs from young donors. Differences in proliferative potential may be seen under conditions requiring extensive hematopoietic proliferation, but not in steady-state hematopoiesis.11 Indeed, basal hematologic parameters show no change with age12 except for lower lymphocyte (Ly) counts,13 yet a significantly reduced reserve capacity of the bone marrow has been reported in aging mice that were under stress conditions induced by group housing.14

Clinical observations suggested that older patients tolerated high-dose chemoradiotherapy less well than younger patients, although this is far from clear.15-18 Myelosuppression appeared more severe and prolonged in older compared with younger patients treated with chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.17,18 However, it is unclear whether the increased toxicity and poor tolerance of chemotherapy in older patients resulted from the age-related differences in HSC reserve among young and old individuals or differences in functional limitations of nonhematopoietic organs.11 18-20

To address this question, we used an established preclinical canine model and challenged young and elderly dogs with 7 repeated nonlethal doses of total body irradiation (TBI) to a total of 550 cGy over a period close to 1 year and recombinant canine granulocyte–colony stimulating factor (rcG-CSF) following the last dose of TBI. We compared the tempos of hematopoietic recoveries, responses to rcG-CSF treatment, and changes in the telomere restriction fragment (TRF) lengths of neutrophils.

Materials and methods

Laboratory animals

Six young (0.5 year), and 6 elderly (ages 7-10 years; median 8 years) beagles were used in the study. Dogs were either raised at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (Seattle, WA) or purchased from commercial kennels licensed by the US Department of Agriculture. The elderly dogs were in the last third of their life span, which was reported to be 12.5 years in beagles maintained in laboratory kennels.21 However, by 7 or 8 years of age, beagles are already considered to be in senescence due to decline in reproductive capacity and presence of clinical signs of senescence such as gray hair, skin wrinkling, apathy, and lethargy.21 All dogs were immunized for leptospirosis, papillomavirus, distemper, hepatitis, and parvovirus. Research was conducted according to the principles outlined in the Guide for Laboratory Animal Facilities and Care prepared by the National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council. Dogs were housed in kennels certified by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Study design

Seven doses of 100 cGy TBI delivered at 7 cGy/min from 2 opposing 60Co sources22 were scheduled to be given at 6-week intervals. The 6-week intervals between TBI doses were chosen on the basis of previous experiments that showed near-complete recoveries of peripheral blood counts by 6 weeks in dogs subjected to a single dose of 200 cGy TBI.22 In case of incomplete hematopoietic recovery, subsequent TBI doses were to be decreased to 50 cGy. For TBI administration, a randomly assigned elderly dog was paired with a randomly assigned young dog throughout the study. In order to reduce the number of extraneous study variables (eg, subtle changes in supportive care), the last experimental dogs were irradiated within 2 weeks of the first dogs. After the seventh TBI dose, dogs received rcG-CSF (Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) at 5 μg/kg per day for 21 days in order to provide an additional hematopoietic challenge. Subsequently, dogs were observed for at least 2 more months. During the course of the study, dogs were examined at least twice daily. Upon completion of studies or if clinically appropriate, dogs were euthanized and underwent complete necropsies with histologic examinations of skin, lungs, heart, stomach, duodenum, small and large bowel, liver, pancreas, kidneys, bladder, spleen, and bone marrow.

Assessment of hematopoietic recoveries and responses to G-CSF treatment

Peripheral blood samples were collected before the first TBI dose and at weekly intervals after each TBI dose. Blood samples were prospectively evaluated for white blood cell counts, platelet (PLT) counts, and hemoglobin concentrations using an automated counter (Sysmex E 2500, Kobe, Japan). Absolute neutrophil counts (ANCs) and Ly counts were calculated from differential counts. Differential counts were evaluated on May-Grunwald-Giemsa–stained smears using standard techniques. At least 200 cells were counted. Recovery of neutrophils following first 6 TBI doses was defined as the first of 2 consecutive days on which the ANCs exceeded 5000/μL following the postradiation nadir. Similarly, PLT recovery was defined as the first of 2 consecutive days on which the PLT counts exceeded 100 000/μL. Individuals whose counts never fell below 5000/μL for ANCs and 100 000/μL for PLTs were assigned recovery times of zero. If recovery did not occur before the next dose of TBI, recovery was truncated at the maximum, which was the last day of the interval (ie, 42 days). Due to the natural differences in the Ly counts among young and old dogs,23 Ly recoveries were measured differently than ANC and PLT recoveries. Ly recoveries were defined as the average of each individual's Ly counts in the final week (sixth week) of recovery following each TBI dose standardized by the baseline values obtained before the first TBI dose. After the seventh TBI dose, cells recoveries were measured as response to rcG-CSF treatment, which included the times to maximum ANC rise, duration of ANC elevation, change in PLT count, and increase in peripheral blood granulocyte-macrophage colony forming units (CFU-GM) formation on day 9 of rcG-CSF treatment.

DNA extraction and telomere length analysis

Neutrophils and mononuclear cell (MNC) fractions were obtained from peripheral blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient separation immediately before the first TBI dose and at the time of study completion. High-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA was extracted after lysis of cell pellets using the Puregene kit (Gentra System, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Telomere lengths were estimated by terminal restriction fragment (TRF) analyses.24 Five μg DNA from granulocytes were digested overnight with restriction enzymes HinfI and RsaI and thereafter with AluI (all from New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) for 6 hours. Integrity of the DNA before and after digestion was monitored by gel electrophoresis. Electrophoreses of digested pre- and post-study samples from each dog (2.5 μg DNA) were performed on 0.5% agarose gels for 1700 Volt-haws. Gels were dried at 60°C for 45 minutes, denatured, neutralized, and hybridized using a32P-labeled telomere probe (TTAGGG)3 at 37°C overnight and exposed to a phosphoimager plate (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, CA). Signals were quantitated by scanning the gel using the Phosphoimage system (Molecular Dynamics). Mean TRF length was assigned to the distance of peak signal intensity measured from the loading point. 32P-labeled HMW DNA marker (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) was included in each gel to calculate the mean TRF size using the Imagequant (Molecular Dynamics) and Fragment (Molecular Dynamics) software programs. Four to 5 replicate experiments (median = 5) were performed for each dog. To determine what constituted a significant difference in TRF, duplicate aliquots from a single DNA sample were loaded in adjacent lanes on the same gel. The average difference between the duplicate samples was 0.67 kb with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.49 kb. Accordingly, the lower limit of detection of significant telomere length differences using this method was then defined as the average +3 SD or 2.14 kb.

CFU-GM assay

CFU-GM assays were carried out as previously described.25 Briefly, MNCs separated over Ficoll-Hypaque gradient were cultured at 0.5 × 106/plate for 14 days at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator in 35-mm plastic Petri dishes containing 2 mL of Iscoves modified Dulbecco medium (Gibco) supplemented with 25% fetal calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT), 1.2% methylcelluose (Sigma, St Louis, MO), 1.2% bovine serum albumin (HyClone) and 12% beef embryo extract (Gibco). Canine growth factors (stem cell factor, rcG-CSF, and rcGM-CSF; Amgen, CA), each at final concentrations of 100 ng/mL, were added to the cultures along with 3 units of human erythropoietin (Amgen). All cultures were performed in triplicates. Colonies were scored on day 14 of culture.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as medians with ranges. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized to determine statistical significance of differences between medians. For cell recoveries, because of the large number of statistical comparisons being made, P values between .01 and .05 could be viewed as suggestive and P values less than .01 as significant.

Results

Blood cell counts before the study

Before the first TBI dose, ANCs, PLTs, and Ly counts in all dogs were within normal limits.23 Median ANC (8800/μL) and PLT counts (471 000/μL) of elderly dogs were not significantly different from median ANC (9100/μL) and PLT counts (467 000/μL) of young dogs (P = .81 and P = 1.0, respectively). Differences in Ly counts noted between current young (4660/μL) and elderly dogs (1980/μL) (P = .03) were consistent with age-related differences in Ly counts reported for young and adult dogs.23

Recoveries of blood cell counts during the study

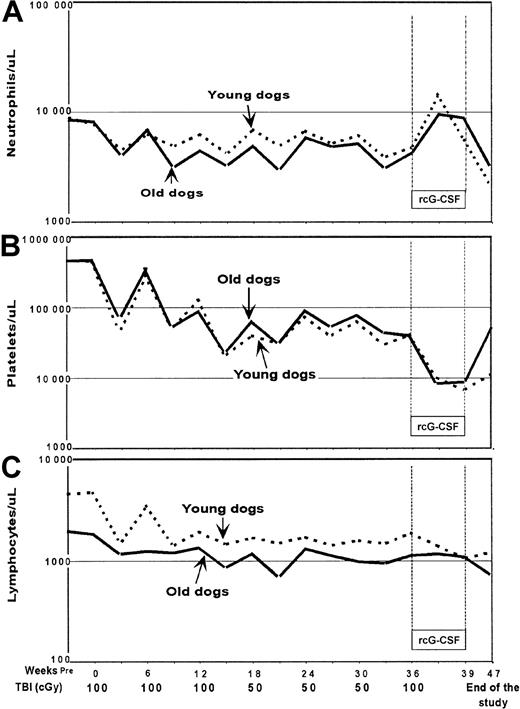

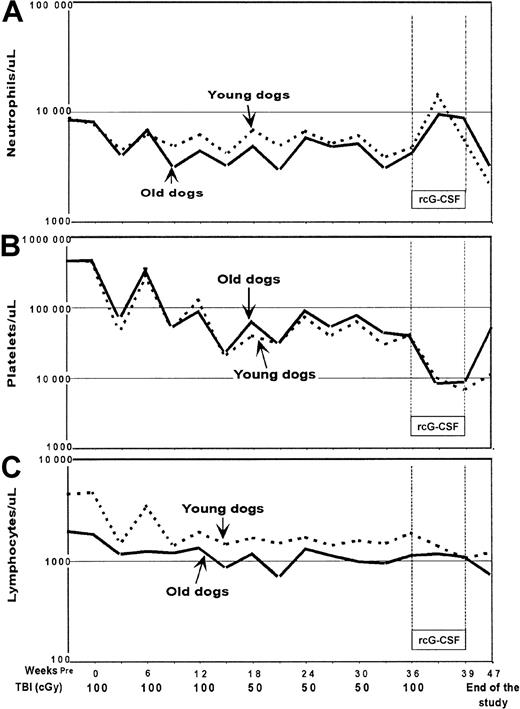

Figure 1 illustrates median ANC (Panel A), PLT (Panel B), and Ly (Panel C) count changes in the 2 groups of dogs. ANC changes were similar in young and elderly dogs and median nadirs remained above 1000/μL throughout the study. PLT counts decreased gradually and comparably in young and elderly dogs throughout the study with the lowest median counts (< 10 000/μL) seen during rcG-CSF treatment. Due to concerns about incomplete PLT recoveries seen after the third TBI dose, the fourth through sixth TBI doses were reduced to 50 cGy. No statistically significant differences in ANC (Table 1) and PLT recoveries (Table2) after each dose of TBI were seen between young and elderly dogs. This included ANC and PLT changes after the seventh TBI dose, which was followed by rcG-CSF treatment (Table3). The increases in ANCs seen during rcG-CSF treatment were contrasted by rapid and prolonged declines in PLT counts that were significantly more pronounced than the declines in PLT counts following the preceding TBI doses without rcG-CSF (P < .01). Absolute Ly counts were slightly higher in young dogs throughout the study. Analyses of Ly counts at TBI dose intervals did not reveal any significant differences in the patterns of recovery over time, although there was some suggestion of worse recovery among younger dogs (Table 4).

Median counts after each dose of total body irradiation in young and old dogs.

Count recoveries for (A) neutrophil, (B) platelet, and (C) lymphocyte were not different among young and old dogs.

Median counts after each dose of total body irradiation in young and old dogs.

Count recoveries for (A) neutrophil, (B) platelet, and (C) lymphocyte were not different among young and old dogs.

Clinical outcomes and changes in marrow morphology

Two of the elderly and 3 of the young dogs were euthanized within 2 to 5 weeks of the last TBI dose because of persistent thrombocytopenia, the development of refractoriness to random PLT transfusions, and consequently, bleeding. The other 7 dogs completed the study. At study completion, one elderly and one young dog had severe pancytopenias and hypocellular marrows, and 2 elderly dogs and one young dog had isolated thrombocytopenias with decreased numbers of megakaryocytes in their marrows whereas their ANCs remained within normal limits. Finally, one elderly and one young dog had normocellular marrows and normal peripheral blood cell counts.

Responses to G-CSF treatment

Table 3 summarizes the responses to rcG-CSF treatment in young and elderly dogs. The times to maximum ANC increase following initiation of rcG-CSF were similar between the 2 groups of dogs, as were the magnitudes of increases in ANC, the duration of ANC elevations, and the increase in peripheral blood CFU-GM on day 9 of rcG-CSF treatment.

Changes in telomere lengths

In both groups of dogs, neutrophil TRF lengths were significantly reduced at completion of the study compared with before study entry (P = .03 for both groups, Table5). The median loss of TRF length in young dogs was 3.8 kb (range 1.6-5.9 kb), a result which was not significantly different from the median loss of 3.2 kb (range 2.4-3.7 kb) observed in elderly dogs. There was no apparent correlation between the TRF loss and clinical outcome.

Nonhematopoietic organ toxicities

There was no clear evidence of regimen-related toxicities in all nonhematopoietic organs studied except from a slight nodular regeneration of the liver in one young dog (E048). One young dog (E047) had an amyloid infiltration of unknown etiology in spleen and lymph nodes. The oldest dog in the study (C269, 10 years old) had evidence of a benign mammary tumor. Three dogs (2 elderly: C269, C398; and one young: E047), which were euthanized before completion of the study due to refractory thrombocytopenia and bleeding, had hemorrhagic changes in the small and large bowels.

Discussion

The number of human beings older than 60 years has been increasing steadily. Because over half of the diagnosed cases of hematologic malignancies occur in this age group, one may expect an increasing number of elderly patients requiring chemotherapy or radiotherapy.16 Thus, studies addressing age-related changes in the response of the hematopoietic system to cytotoxic therapy are needed.

Current experimental data have led to the consensus that age-related deficits in hematopoiesis tended to be subtle, and were seen only under conditions of extreme hematopoietic stress.11,12,26,27Such conditions were created experimentally in mice either by using serial HSC transplantation models,3,27,28 competitive repopulating assays,29-31 or challenges of HSCs through repeated exposures of animals to cytotoxic agents.32,33Serial transplantation studies showed that ages of the initial HSC donors had little effect on the engraftment potential of HSCs.2,27,28 These results, however, might be seriously affected by damage to HSCs through repeated ex vivo handling.32,34 Studies of competitive repopulation assays gave conflicting results perhaps related to strong genetic background influences on underlying HSC pool size and proliferation potential among different mouse strains used.35-37

In the current study, we compared the HSC recovery potential in randomly bred elderly and young dogs which involved administration of repeated nonmyeloablative TBI with 6-week interfraction intervals resulting in partial hematopoietic suppression followed by endogenous regeneration. To our knowledge, this approach has not been used in a large animal model to assess age-related changes in HSC potential. Many clinically used chemotherapy regimens are administered at 6-week intervals. Here, we chose TBI over chemotherapy given the well-known stem cell toxic effects of photon irradiation and the ease of both its dosimetry and administration. Elderly dogs were paired with young ones for the 11-month course of study. We hypothesized that older animals would have delayed hematopoietic recoveries compared with young ones. Within the limitation of the experimental design, our results showed that both neutrophil and platelet recoveries after each dose of TBI and the responses to rcG-CSF treatment after the last dose of TBI were similar in young and elderly animals. Lymphocyte counts in young dogs had more prolonged declines than those in elderly dogs, though the differences were only suggestive given the multiple comparisons made. Whether this observation is reflective of the presence of larger percentages of circulating long-lived memory T lymphocytes thought to be more resistant to radiation38 in elderly dogs and relatively more radiation-sensitive naı̈ve T cells in younger dogs remains conjectural.

At the completion of the study, there were comparable numbers of animals in both groups showing either pancytopenias and hypocellular marrows, or relatively normal marrow cellularities. In some cases, one member of a treatment pair developed pancytopenia whereas the other did not. This points to factors other than TBI dose that may be associated with heterogeneity of hematopoietic responses such as the individual dogs' HSC numbers26 or radiosensitivities.39Our findings are also consistent with recently published data indicating that age is not a biologically adverse parameter for patients with multiple myeloma receiving high-dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell support.40

Serial hematopoietic depletion with cytotoxic agents has been previously established as a method to study the regenerative ability of bone marrow cells. Results obtained were dependent on the doses and types of cytotoxic agents used and whether a given agent was toxic not only to committed hematopoietic progenitor cells but also to HSCs.32,41,42 In this study, several elderly and young dogs showed signs of hematopoietic exhaustion as early as after the third dose of TBI as manifested by incomplete PLT recoveries. This necessitated the reduction of 3 subsequent TBI doses to 50 cGy. Signs of hematopoietic exhaustion were also reported in mice repeatedly challenged with sublethal irradiation.33 Current results were somewhat at variance with those of Valentine et al43who subjected cats to 200 rad (≈150 cGy; dose rate and TBI source not given) delivered at 4-month intervals (total dose ≈750 cGy). Hematopoietic regeneration of cats after the fifth dose of TBI was as prompt and complete as after the first dose. Assuming that the numbers and radiosensitivity of HSCs in dogs are comparable to those in cats, differences in results may be explained by differences in interfraction intervals between the 2 studies (1.5 vs 4 months).

To amplify any putative differences in hematopoietic responses among young and old dogs, we initiated G-CSF treatment following the last dose of TBI. Even so, no differences were observed. These findings were in agreement with studies in otherwise healthy human volunteers, which revealed no significant differences among elderly and young individuals regarding the effect of rhG-CSF on peripheral blood cell counts, marrow neutrophil numbers, and their kinetics, except for a trend for less-effective mobilization of blood cell progenitors to the peripheral blood in older individuals.11 44

Administration of rcG-CSF following the last dose of TBI in the current study led to rapid and prolonged declines in PLT counts. In fact, some of the dogs never recovered or improved their PLT counts even after cessation of G-CSF treatment. G-CSF administration in normal dogs45 and, similarly, healthy human volunteers,44 did not significantly change PLT counts. Therefore, current findings are consistent with the notion that G-CSF administration could be detrimental to PLT recovery when the hematopoietic reserve was impaired. Similar observations were made in human patients after transplantation of low numbers (< 5 × 106/kg) of autologous CD34+ cells, in whom posttransplant administration of G-CSF resulted in highly significant delays in PLT recoveries.46 Whether this was the result of G-CSF–induced damage to the HSC pool and loss of marrow reserve as proposed by van Os47 and others48 was not clear.

The differences in telomere length among young and old dogs observed prior to initiation of the study were expected from previous reports in humans documenting the effect of age on telomere length.8,9 However, during the study the extent of telomere shortenings was equivalent among young and elderly dogs. This indicated that HSCs underwent comparable numbers of divisions in young and elderly dogs in response to stress conditions that were imparted by the study design. The fact that elderly dogs had in vivo responses that were similar to those of young dogs despite their shorter telomeres at commencement of the study is in apparent contrast to findings made in telomerase-deficient mice, which suggested a relationship between telomere length and hypersensitivity to ionizing radiation.49 However, the increased sensitivity to ionizing radiation was only observed in the fifth generation telomerase-deficient mice, with 40% reduction in telomeres, but not in the second generation telomerase-deficient mice, with shortening of telomeres similar to that (≈10-15%) observed among young and old dogs before study entry. This would suggest that other mechanisms affect the radiation sensitivity when telomeres are sufficiently long.

Current results suggest that replicative senescence of HSCs did not play a prominent role in hematopoietic responses to toxic injuries in dogs. This suggests that poor tolerance of radio/chemotherapeutic regimens in older human patients might rather be due to genetic factors relating to cell repair,50 or senescence51and dysfunction of organs other than bone marrow.52-54

The authors are grateful to the technicians of the Shared Canine Resource and the Hematology and Transplantation Biology Laboratories (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center) for their technical assistance. We thank Barbara Johnston, DVM, who provided veterinary support. We are very grateful to Helen Crawford, Bonnie Larson, Lori Ausburn, Sue Carbonneau, and Karen Carbonneau for their outstanding secretarial support. G.M. received a Young Investigator Award presented by the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Alexandria, VA. Cyclosporine (Sangcya, Cyclosporine oral solution) was generously provided by Sangstat, Fremont, CA, and Mycophenolate Mofetil was provided by Roche, Nutley, NJ.

Supported in part by grants CA 78902, HL 36444, DK 42716, and CA 15704 from the National Institutes of Health, DHHS, Bethesda, MD. J.M.Z. is a postdoctoral fellow from the Department of Hematology, University Medical School, Gdańsk, Poland; and is also a recipient of the International Fellowship for Young PhDs, awarded by the Foundation for Polish Science, Warsaw, Poland. M.-T.L. received additional support from a Lady Tata Memorial Trust International Research grant, London, United Kingdom. R.S. also received support from the Laura Landro Salomon Endowment Fund, New York, NY; and through a prize awarded by the Josef Steiner Krebsstiftung, Bern, Switzerland.

Correspondence:Rainer Storb, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Ave North, D1-100, PO Box 19024, Seattle, WA, 98109-1024; e-mail: rstorb@fhcrc.org.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.