Cysteine-rich 61 (Cyr61, CCN1) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, CCN2) are growth factor–inducible immediate-early gene products found in blood vessel walls and healing cutaneous wounds. We previously reported that the adhesion of endothelial cells, platelets, and fibroblasts to these extracellular matrix–associated proteins is mediated through integrin receptors. In this study, we demonstrated that both Cyr61 and CTGF are expressed in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of apolipoprotein E–deficient mice. Because monocyte adhesion and transmigration are important for atherosclerosis, wound healing, and inflammation, we examined the interaction of THP-1 monocytic cells and isolated peripheral blood monocytes with Cyr61 and CTGF. THP-1 cells and monocytes adhered to Cyr61- or CTGF-coated wells in an activation-dependent manner and this process was mediated primarily through integrin αMβ2. Additionally, expression of αMβ2 on human embryonic kidney 293 cells resulted in enhanced cell adhesion to Cyr61. Consistent with these data, a GST-fusion protein containing the I domain of the integrin αM subunit bound specifically to immobilized Cyr61 or CTGF. We have also investigated the requirement of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) as coreceptors for monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. Pretreatment of monocytes with heparin or heparinase I resulted in partial inhibition of cell adhesion to Cyr61. However, monocytes, but not fibroblasts, were capable of adhering to a Cyr61 mutant deficient in heparin binding activity. Collectively, these results show that activated monocytes adhere to Cyr61 and CTGF through integrin αMβ2 and cell surface HSPGs. However, unlike fibroblast adhesion to Cyr61, cell surface HSPGs are not absolutely required for this adhesion process.

Introduction

Cysteine-rich 61 (Cyr61) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) belong to the Cyr61/CTGF/nephroblastoma-overexpressed (CCN) family of matricellular signaling molecules capable of mediating diverse biologic functions.1,2 Other members in this protein family include Nov, WISP-1, WISP-2, and WISP-3. These proteins are characterized by the presence of an N-terminal secretory signal, followed by 4 conserved structural domains, which include: (1) an insulinlike growth factor–binding protein homology domain, (2) a von Willebrand factor type C domain, (3) a thrombospondin type 1 repeat homology domain, and (4) a C-terminal domain with sequence similarities to growth factor cysteine knots. It has been suggested that the C-terminal domain may mediate protein-protein interaction.3 Moreover, 2 putative heparin-binding motifs are present in the C-terminal domain of Cyr61 and mutations of the basic amino acid residues in these motifs abolish heparin-binding affinity of Cyr61.4 WISP-2 and its human homolog are unique in that they lack the C-terminal domain.5 6

Both Cyr61 and CTGF have been identified as products of immediate-early genes that are transcriptionally induced in fibroblasts in response to serum growth factors.7,8 On synthesis, they are secreted and become associated with the cell surface and the extracellular matrix,9,10 suggesting that these proteins may mediate cell-matrix interaction. In functional studies, both Cyr61 and CTGF have been shown to support cell adhesion, induce cell migration, and augment growth factor–induced cell proliferation in vitro4,10-16 and induce angiogenesis in vivo.13,14 Consistent with the adhesive properties of these proteins, 2 other family members, WISP-2 and Nov, have also been found to promote the adhesion of osteoblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells, respectively.6,17 Recently, we have identified several integrins, namely αvβ3, αvβ5, αIIbβ3, and α6β1, as cellular receptors mediating interaction of different cell types with Cyr61 and CTGF.4,12,15,16 In addition, cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) are also required for α6β1-mediated adhesion of human skin fibroblasts to Cyr61.4 Identification of integrins as signaling receptors for Cyr61 and CTGF accounts for most, if not all, of the cellular and biologic activities of these extracellular matrix–associated proteins.

Immunohistochemical studies have localized both Cyr61 and CTGF in the cardiovascular system of developing mouse embryos and adult mice.10,18 Interestingly, CTGF has been shown to be overexpressed in human advanced atherosclerotic lesions as compared to normal blood vessels.19 High expression of CTGF has also been observed under diverse pathologic conditions, suggesting that it may play an important role in various diseases such as systemic scleroderma,20 renal fibrosis,21 and hepatic fibrosis in biliary atresia.22 During cutaneous wound healing, the expression of Cyr61 and CTGF is up-regulated, and therefore these proteins may function downstream of transforming growth factor-β and fibroblast growth factor, strong inducers of Cyr61and CTGF, in wound repair.18 23Because monocyte adhesion and transendothelial migration play a central role in inflammation, atherosclerosis, and wound healing, we sought to examine the interaction of THP-1 cells and peripheral blood monocytes with Cyr61 and CTGF. In this study, we demonstrated that in addition to CTGF, Cyr61 is expressed in atherosclerotic lesions of apolipoprotein E–deficient (apoE−/−) mice. Moreover, monocytes adhere to both Cyr61 and CTGF, and this process is mediated through integrin αMβ2 and cell surface HSPGs. Thus, these findings identified Cyr61 and CTGF as novel ligands for integrin αMβ2, underscoring the importance of these proteins in the pathophysiologic function of monocytes.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and peptides

The anti-αM monoclonal antibodies 2LPM19c and 44a were obtained from Dako (Carpinteria, CA) and Sigma (St. Louis, MO), respectively. The anti-αvβ3(LM609), anti-αX (CBR-p150/4G1), anti-β1(6S6) and anti-β2 (YFC118.3) function-blocking monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). An antiglutathione S-transferase (anti-GST) polyclonal antibody raised in goats was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, NJ) and a rabbit antigoat IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was from Sigma. Polyclonal anti-Cyr61 and anti-CTGF antibodies were raised in rabbits and affinity purified as described previously.10 An antipeptide antibody (anti-Cyr61367–381), raised in rabbits against a peptide sequence corresponding to the extreme C-terminus of Cyr61 (F367PFYRLFNDIHKFRD381; single-letter amino acid codes), was affinity purified against the peptide. Echistatin, an RGD-containing snake venom peptide,24 was obtained from Sigma. Vitronectin and fibronectin were purchased from Sigma and Gibco BRL (Grand Island, NY), respectively. Heparin (sodium salt; from porcine intestinal mucosa) and heparinase I (EC4.2.2.7) were from Sigma.

Protein purification

Recombinant Cyr61 and CTGF, synthesized in a baculovirus expression system using Sf9 insect cells, were purified from serum-free conditioned media by chromatography on Sepharose S as previously described.10,11 A Cyr61 mutant (Cyr61-DM) with alanine substitutions of the basic amino acid residues within the 2 putative heparin-binding motifs at residues 280-290 and residues 306-312 was constructed by splice-overlap extension mutagenesis as previously described.4

Recombinant I domain of the integrin-αM subunit was expressed as a fusion protein with GST (GST-αMI) and purified as previously described.25 Briefly, the region coding for the human αM I domain sequence D132-A318 was amplified and inserted in the expression vector pGEX-4T-1 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). To express GST-αMI, BL-21 Escherichia coli cells were transformed with the above vector and protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 hours at 37°C. The GST-αMI fusion protein was affinity purified from cell lysates using glutathione-agarose (Sigma).

Isolation of peripheral blood monocytes

Acid-citrate-dextrose anticoagulated human blood was collected from healthy donors and centrifuged at 200g for 20 minutes. After removal of the platelet-rich plasma, the buffy coat and packed red cells were diluted 2-fold with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.35, 0.15 M NaCl) and 25 mL of the cell suspension was layered onto 20 ml Ficoll-Paque (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Mononuclear cells were isolated by centrifugation through Ficoll-Paque at 400g for 60 minutes at 4°C, diluted with an equal volume of PBS containing 2 mM EDTA, and sedimented at 400g for 10 minutes. To remove residual platelets, the mononuclear cells were washed twice with modified Tyrode buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.35, 135 mM NaCl, 2.9 mM KCl, 12 mM NaHCO2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.1% dextrose and 0.2% bovine serum albumin [BSA]) by centrifugation at 130g for 10 minutes. To separate lymphocytes from monocytes, the mononuclear cells were resuspended in modified Tyrode buffer and subjected to discontinuous density gradient centrifugation on Percoll (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Peripheral blood monocytes were isolated between Percoll density of 1.047 and 1.050 g/mL, washed twice with modified Tyrode buffer, and resuspended to a final concentration of 2 to 3 × 106 cells/mL. The purity of the monocyte preparations was more than 80% as measured by anti-CD14 (Sigma) staining in flow cytometry, and cell viability was more than 98% as judged by trypan blue exclusion.

Cell culture and cell adhesion assay

The THP-1 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were maintained in RPMI 1640 media (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mMl-glutamine, 1% nonessential amino acid solution, 100 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1.5 g/L NaHCO2, and antibiotics. Cells were grown to 1 × 106/mL and serum starved for 24 hours prior to cell adhesion experiments. Microtiter wells (Immulon 2 Removawell strips, Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA) were coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61 or CTGF for 2 hours at 37°C and blocked with 1% BSA for 1 hour at 37°C. THP-1 cells, suspended in modified Tyrode buffer containing 0.1% BSA and 1 mM CaCl2, were added to the wells (100 μL/well) and incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing and adherent cells were fixed and stained with 1% methylene blue. Cellular dye was extracted with acid-ethanol and cell adhesion was quantified by A650 as described.26

For the adhesion of peripheral blood monocytes, Cyr61-coated wells were blocked with 0.15% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Sigma) for 30 minutes at 37°C and cell adhesion proceeded as described above. Adherent cells were quantified using the acid phosphatase assay27 by incubation with the substrate solution (0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5, 10 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate, and 0.1% Triton X-100; 100 μL/well) for 2 hours at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 15 μL 1 N NaOH and A450 was measured. In inhibition studies, monocytes were preincubated with antibodies, peptides, or EDTA for 30 minutes at 37°C prior to addition to microtiter wells. The αMβ2-expressing human embryonic kidney 293 cells used in the adhesion assay have been previously described.28 In cell adhesion experiments, microtiter wells were coated with 1 μg/mL Cyr61 and blocked with 0.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone (Sigma). The cells were labeled with NaCrO4 (0.5 mCi/mL [18.5 MBq/mL]), and the adhesion of 51Cr-labeled cells to Cyr61-coated wells was performed as described.28

Binding assay of GST-αMI fusion protein to immobilized Cyr61 and CTGF

Microtiter wells were coated with Cyr61 or CTGF for 24 hours at 4°C and blocked with 0.15% PVA for 30 minutes at 37°C. GST-αMI fusion protein (1 μM), preincubated with or without antibodies for 30 minutes at 37°C, was added to the wells and incubated for 2 hours at 22°C. Unbound GST-αMI was removed by washing with 30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.3, 0.2 M NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% PVA. Bound GST-αMI was detected by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a polyclonal anti-GST antibody followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were detected usingo-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (Sigma) as the substrate. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 25 μL 6 N HCl and A490 was measured.

Immunohistochemistry studies

Retired breeders of apoE−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and killed by cervical dislocation under ether anesthesia. Their hearts with aortas were removed, fixed in 4% formaldehyde, frozen, and sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm on a cryostat. Sectioning began at the juncture of the aorta to the heart and continued toward the aortic arch covering a distance of 400 to 500 μm. The frozen sections were collected onto poly-l-lysine–coated coverslips and advanced atherosclerotic lesions were located by light microscopy. The sections were treated with 0.03% H2O2 to inactivate endogenous peroxidase, blocked with 3% normal goat serum, and incubated with anti-Cyr61 and anti-CTGF antibodies for 1 hour at 22°C. After washing, bound antibodies were detected with a biotinylated goat antirabbit antibody followed by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase labeling system using diaminobenzidine as the substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin.10

Results

Immunohistochemical localization of Cyr61 and CTGF in advanced atherosclerotic lesions in apoE−/− mice

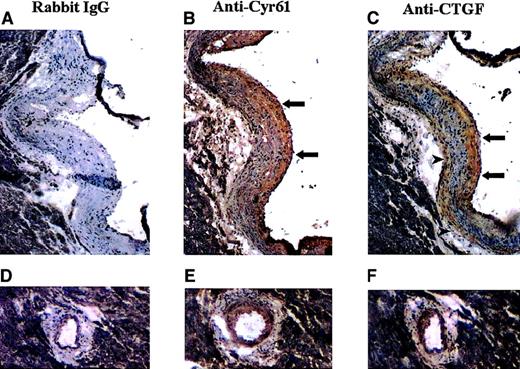

It has been reported that CTGF is overexpressed in advanced atherosclerotic lesions in humans,19 which is likely due to growth factor stimulation of endothelial cells, aortic smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts at the lesion sites. Because Cyr61 is also transcriptionally induced in fibroblasts in response to serum growth factors,7 we examined whether the expression of Cyr61 is up-regulated in advanced atherosclerotic lesions. In these studies, we used the apoE−/− mice, which have been shown to develop advanced atherosclerotic lesions similar to those found in humans.29-32 Frozen sections of the mouse atherosclerotic lesions were taken through the midpoint of the aortic valve with the lesion occupying approximately 95% of the circumference of the aortic wall. As shown in Figure 1, panels A through C, both the subendothelial intimal space and the media were markedly thickened exhibiting characteristics of human atherosclerotic lesions. To examine the expression of Cyr61 and CTGF in the mouse lesions, immunohistochemical staining was performed with anti-Cyr61 and anti-CTGF polyclonal antibodies. These antibodies were raised against recombinant protein fragments corresponding to the central variable regions of these proteins. On immunoblots, anti-Cyr61 and anti-CTGF reacted specifically with Cyr61 and CTGF, respectively, and no cross-reactivity was detected.10 Intense staining for Cyr61 was observed primarily in the subintimal regions of the lesion (Figure 1B, arrows). Similarly, CTGF was stained positively in the subintimal regions (Figure 1C, arrows) and also to a lesser degree just medial to the external elastic membrane (Figure 1C, arrowheads). The coronary artery also developed lesions with eccentric thickening of the intima and media, which were also stained positively with both antibodies (Figure 1E,F). By contrast, control sections incubated with normal rabbit IgG displayed minimal staining (Figure 1A,D).

Immunohistochemical localization of Cyr61 and CTGF in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of ApoE−/− mice.

Frozen serial sections were taken from the heart at the aortic valve where prominent atherosclerotic lesions had formed. Sections were treated with H2O2, blocked with normal goat serum, and incubated with normal rabbit IgG (A,D), anti-Cyr61 (B,E), or anti-CTGF (C,F). Antibody localization was detected with a biotinylated secondary antibody, followed by the avidin-biotin-HRP labeling system using diaminobenzidine as the substrate. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Lesions located at the aortic valve (A-C) and coronary artery (D-F) are shown.

Immunohistochemical localization of Cyr61 and CTGF in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of ApoE−/− mice.

Frozen serial sections were taken from the heart at the aortic valve where prominent atherosclerotic lesions had formed. Sections were treated with H2O2, blocked with normal goat serum, and incubated with normal rabbit IgG (A,D), anti-Cyr61 (B,E), or anti-CTGF (C,F). Antibody localization was detected with a biotinylated secondary antibody, followed by the avidin-biotin-HRP labeling system using diaminobenzidine as the substrate. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin. Lesions located at the aortic valve (A-C) and coronary artery (D-F) are shown.

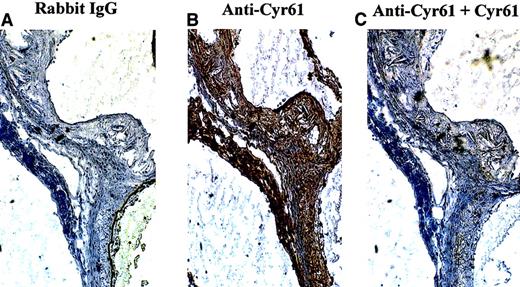

To demonstrate further the specificity of Cyr61 expression in atherosclerotic lesions, immunohistochemistry was performed with an antipeptide antibody (anti-Cyr61367–381) directed against the C-terminus of Cyr61, a region of unique sequence identity in Cyr61. On immunoblots, anti-Cyr61367–381 reacted with as little as 10 ng Cyr61 with no cross-reactivity with as much as 1 μg CTGF (data not shown). As expected, intense staining of the mouse lesions was observed with anti-Cyr61367–381 (Figure2B), and pretreatment of the antipeptide antibody with Cyr61 protein completely abolished this staining (Figure2C). Together, these results indicate that both Cyr61 and CTGF are expressed in atherosclerotic lesions of apoE−/− mice.

Specificity of immunohistochemical staining of Cyr61 in mouse atherosclerotic lesions.

Frozen serial sections, taken from the hearts of ApoE−/−mice, were incubated with rabbit IgG (A) or anti-Cyr61367–381 (B,C). To demonstrate staining specificity in panel C, anti-Cyr61367–381 was preabsorbed with 5 μg/mL recombinant Cyr61 for 16 hours at 4°C prior to its application to the sections. Immunohistochemical staining was performed as described in the legend of Figure 1.

Specificity of immunohistochemical staining of Cyr61 in mouse atherosclerotic lesions.

Frozen serial sections, taken from the hearts of ApoE−/−mice, were incubated with rabbit IgG (A) or anti-Cyr61367–381 (B,C). To demonstrate staining specificity in panel C, anti-Cyr61367–381 was preabsorbed with 5 μg/mL recombinant Cyr61 for 16 hours at 4°C prior to its application to the sections. Immunohistochemical staining was performed as described in the legend of Figure 1.

Activation-dependent adhesion of THP-1 cells and peripheral blood monocytes to Cyr61 and CTGF

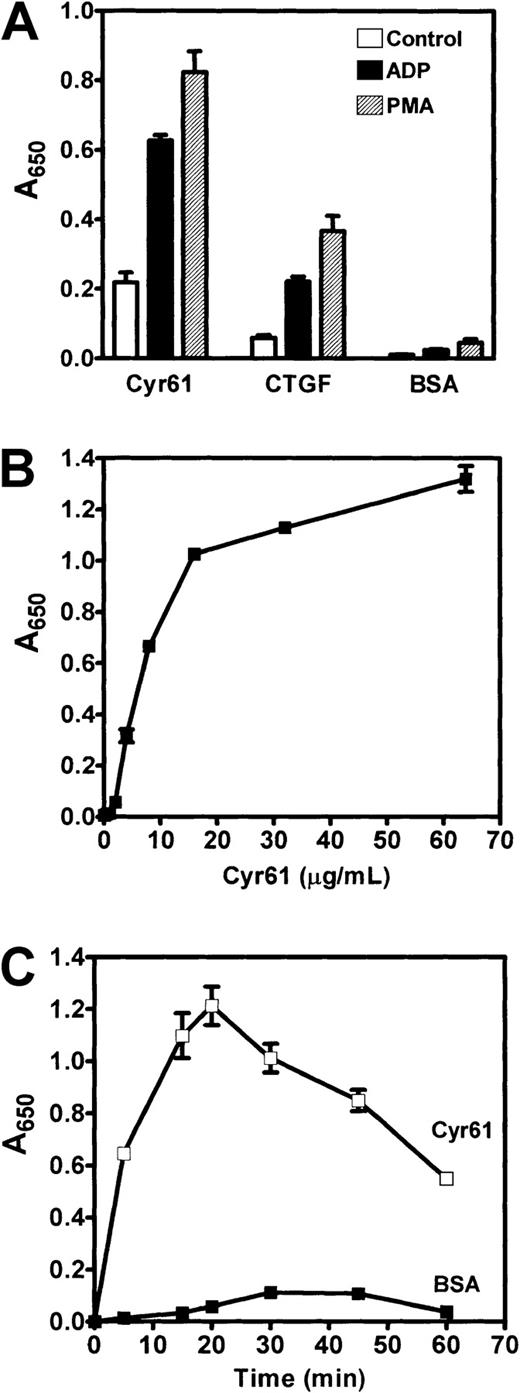

We previously reported that Cyr61 and CTGF induce cell adhesion and migration through interaction with integrin receptors.4 12-16 Because monocyte/macrophage-derived foam cells are present in subintimal regions of atherosclerotic lesions where the expression of Cyr61 and CTGF are prominent, we examined possible interaction of these mononuclear blood cells with Cyr61 and CTGF. In initial studies, cultured THP-1 monocytic cells were used to establish optimal conditions for cell adhesion to these proteins. In these experiments, THP-1 cells were activated with 20 μM adenosine diphosphate (ADP) or 20 nM phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and allowed to adhere to microtiter wells coated with recombinant Cyr61 or CTGF. As controls, cell adhesion to BSA-coated wells was performed. The adherent cells were fixed, stained with methylene blue, and quantified by measuring A650 of the extracted dye. Figure3A shows that THP-1 cells adhered to both Cyr61- and CTGF-coated wells, but not to control wells coated with BSA. Moreover, cellular activation with ADP resulted in an approximate 3-fold enhancement of cell adhesion to both proteins. An approximate 4-fold increase in cell adhesion was also observed with PMA stimulation. In 3 separate experiments, we consistently observed higher adhesion of THP-1 cells to Cyr61- than to CTGF-coated wells. Thus, in later experiments, we used Cyr61 as the prototype substrate to mediate cell adhesion.

Adhesion of THP-1 cells to Cyr61 and CTGF.

(A) Washed THP-1 cells were incubated with vehicle buffer (control), 20 μM ADP, or 20 nM PMA as indicated and added to microtiter wells (1 × 105 cells/well) coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61, CTGF, or BSA. Cell adhesion proceeded for 20 minutes at 37°C. (B) THP-1 cells were stimulated with 20 μM ADP, added to wells coated with the indicated concentrations of Cyr61, and allowed to adhere for 20 minutes at 37°C. (C) ADP-stimulated THP-1 cells were added to wells coated with 15 μg/mL Cyr61 or BSA and incubated for the indicated times. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing. Adherent cells were fixed, stained with methylene blue, and A650 of the extracted dye was measured. Data presented are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figures are representative of 3 experiments.

Adhesion of THP-1 cells to Cyr61 and CTGF.

(A) Washed THP-1 cells were incubated with vehicle buffer (control), 20 μM ADP, or 20 nM PMA as indicated and added to microtiter wells (1 × 105 cells/well) coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61, CTGF, or BSA. Cell adhesion proceeded for 20 minutes at 37°C. (B) THP-1 cells were stimulated with 20 μM ADP, added to wells coated with the indicated concentrations of Cyr61, and allowed to adhere for 20 minutes at 37°C. (C) ADP-stimulated THP-1 cells were added to wells coated with 15 μg/mL Cyr61 or BSA and incubated for the indicated times. Nonadherent cells were removed by washing. Adherent cells were fixed, stained with methylene blue, and A650 of the extracted dye was measured. Data presented are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figures are representative of 3 experiments.

To further characterize the adhesion of THP-1 cells to Cyr61, we examined dose and time dependency of this process. As shown in Figure3B, the adhesion of ADP-stimulated THP-1 cells to Cyr61 was dose dependent with saturable adhesion occurring at a coating concentration of approximately 15 μg/mL. Time-course studies in Figure 3C show that the adhesion process was transient, peaking at 20 minutes and declining thereafter. These results suggest that the adherent cells became detached from immobilized Cyr61 in a time-dependent manner. This transient nature of leukocyte adhesion has also been observed for T-lymphoblastoid Jurkat cell adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule–1 and to the CS-1 peptide of fibronectin.33

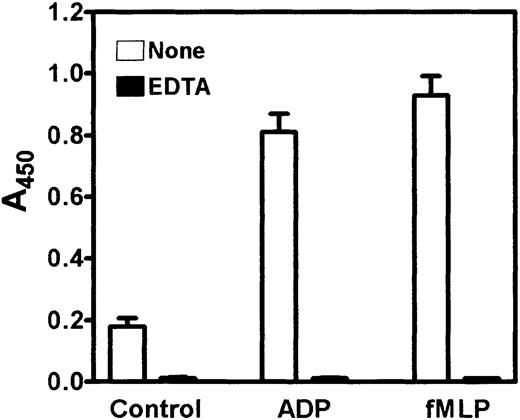

Having established conditions for the adhesion assay, we proceeded to examine the adhesion of human peripheral blood monocytes to Cyr61. Unless otherwise indicated, isolated monocytes were added to microtiter wells coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61 and adhesion proceeded for 20 minutes at 37°C. Because of the limited recovery of peripheral blood monocytes from the isolation procedure, cell adhesion was quantified using a more sensitive method by measuring the acid phosphatase activity of the adherent cells. Figure 4shows that unactivated monocytes adhered poorly to Cyr61-coated wells. However, cellular activation with 20 μM ADP or 1 μM formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP)34 resulted in a dramatic increase in monocyte adhesion to Cyr61-coated wells. Quantitation of acid phosphatase activities of adherent versus added cells indicated that approximately 40% to 50% of input monocytes adhered to Cyr61, and this level of cell adhesion was comparable to those using vitronectin or fibrinogen as the adhesive substrates (Figure5A,C). Preincubation of the cell suspension with 2 mM EDTA completely abolished the adhesion of unactivated and activated monocytes to Cyr61 (Figure 4). These results indicate that the adhesion process is activation and divalent cation dependent, consistent with the involvement of integrin receptors.

Activation-dependent adhesion of peripheral blood monocytes to Cyr61.

Isolated monocytes were preincubated with or without 2 mM EDTA for 30 minutes, and added to microtiter wells (2-3 × 105cells/well) coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61 in the presence of vehicle buffer (control), 20 μM ADP, or 1 μM fMLP. After incubation for 20 minutes at 37°C, nonadherent cells were washed and adherent cells were detected by the acid phosphatase assay. Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figure is representative of 2 experiments.

Activation-dependent adhesion of peripheral blood monocytes to Cyr61.

Isolated monocytes were preincubated with or without 2 mM EDTA for 30 minutes, and added to microtiter wells (2-3 × 105cells/well) coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61 in the presence of vehicle buffer (control), 20 μM ADP, or 1 μM fMLP. After incubation for 20 minutes at 37°C, nonadherent cells were washed and adherent cells were detected by the acid phosphatase assay. Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figure is representative of 2 experiments.

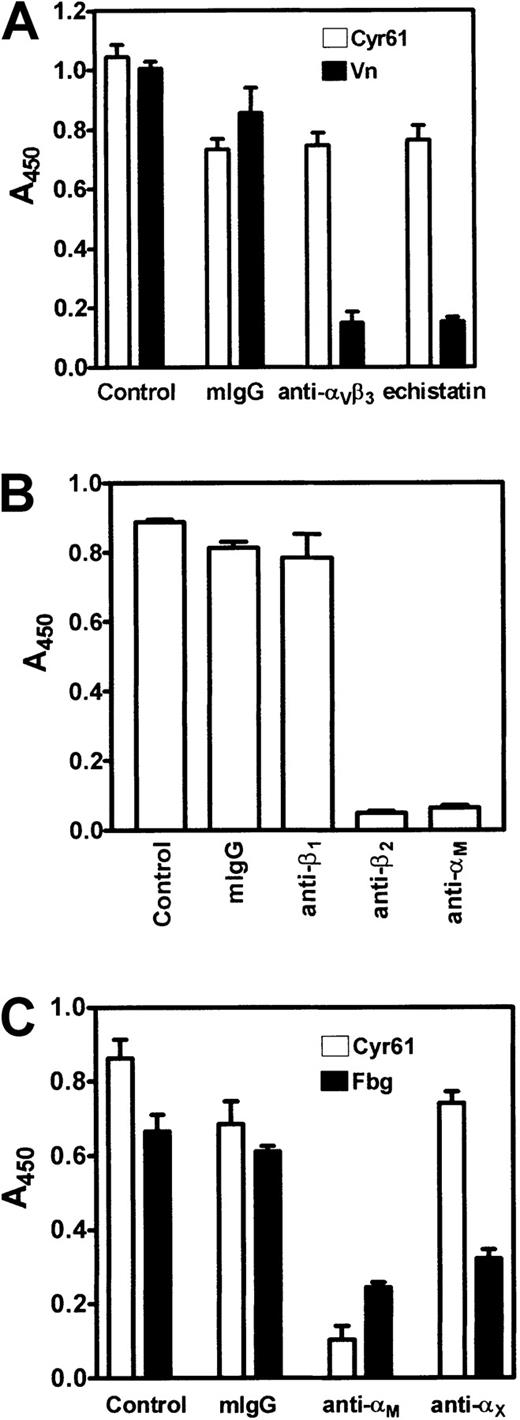

Inhibition of monocyte adhesion to Cyr61.

Isolated monocytes were preincubated with inhibitors for 30 minutes at 37°C, then activated with 20 μM ADP, and allowed to adhere for 20 minutes at 37°C to microtiter wells coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61, 10 μg/mL vitronectin, or 15 μg/mL fibrinogen as indicated. Cell adhesion was measured by the acid phosphatase assay. (A) Monocytes were pretreated with vehicle buffer (control), 200 nM mouse IgG (mIgG), 200 nM LM609 (anti-αvβ3), or 1 μM echistatin. Cell adhesion to Cyr61 (open bars) or vitronectin (closed bars) was performed. (B) Monocytes were pretreated with vehicle buffer (control), 200 nM mouse IgG (mIgG), 6S6 (anti-β1), YFC118.3 (anti-β2), or 2LPM19c (anti-αM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cell adhesion to Cyr61 was performed. (C) Monocytes, pretreated with vehicle buffer (control), 200 nM mouse IgG, 2LPM19c (anti-αM), or CBR-p150/4G1 (anti-αX) for 30 minutes at 37°C, were allowed to adhere to Cyr61 (open bars) or fibrinogen (closed bars). Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs.

Inhibition of monocyte adhesion to Cyr61.

Isolated monocytes were preincubated with inhibitors for 30 minutes at 37°C, then activated with 20 μM ADP, and allowed to adhere for 20 minutes at 37°C to microtiter wells coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61, 10 μg/mL vitronectin, or 15 μg/mL fibrinogen as indicated. Cell adhesion was measured by the acid phosphatase assay. (A) Monocytes were pretreated with vehicle buffer (control), 200 nM mouse IgG (mIgG), 200 nM LM609 (anti-αvβ3), or 1 μM echistatin. Cell adhesion to Cyr61 (open bars) or vitronectin (closed bars) was performed. (B) Monocytes were pretreated with vehicle buffer (control), 200 nM mouse IgG (mIgG), 6S6 (anti-β1), YFC118.3 (anti-β2), or 2LPM19c (anti-αM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cell adhesion to Cyr61 was performed. (C) Monocytes, pretreated with vehicle buffer (control), 200 nM mouse IgG, 2LPM19c (anti-αM), or CBR-p150/4G1 (anti-αX) for 30 minutes at 37°C, were allowed to adhere to Cyr61 (open bars) or fibrinogen (closed bars). Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs.

Identification of αMβ2 as the major integrin mediating monocyte adhesion to Cyr61

In previous studies, we demonstrated that the adhesion of endothelial cells, platelets, and fibroblasts to Cyr61 and CTGF is mediated through interaction with integrins αvβ3, αIIbβ3, and α6β1, respectively.4,12,15It has been reported that human monocytes express a small quantity of functional αvβ3.35 By flow cytometry analyses, we also found that ADP-activated monocytes stained positively with 2 anti-αvβ3 monoclonal antibodies, LM609 and anti-VnR1 (results not shown). Thus, we evaluated the role of this integrin in mediating monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. Figure 5A shows that LM609 (anti-αvβ3) caused little inhibition of the adhesion of ADP-activated monocytes to Cyr61. Likewise, echistatin, a high-affinity RGD-containing snake venom peptide,24 blocked monocyte adhesion to Cyr61 by only 20%. However, in parallel samples, both compounds effectively inhibited monocyte adhesion to vitronectin by more than 85%. These results suggest that integrin αvβ3 is not the major adhesion receptor on monocytes mediating interaction with Cyr61.

To identify which integrin(s) on monocytes may be involved in this adhesion process, we examined the effect of monoclonal antibodies directed against different integrin subunits. As shown in Figure 5B, monocyte adhesion to Cyr61 was completely blocked by an anti-β2 antibody (YFC118.3), but not by mouse IgG or an anti-β1 antibody (6S6). The lack of effect of 6S6 was not due to the inaccessibility of the antibody to β1integrins on monocytes because it inhibited monocyte adhesion to fibronectin by about 60% in control samples (results not shown). In addition to the anti-β2 antibody, 2 monoclonal antibodies directed against the αM subunit, 2LPM19c (Figure 5B) and 44a (results not shown), also caused complete inhibition of monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. These results suggest that integrin αMβ2 serves as an adhesion receptor on monocytes for interaction with Cyr61. Because integrins αMβ2 and αXβ2share some common ligand specificity,36 we examined possible interaction of Cyr61 with αXβ2 on monocytes. As shown in Figure 5C, an anti-αX antibody (CBR-p150/4G1) had no significant effect on monocyte adhesion to Cyr61, whereas an anti-αM antibody (2LPM19c) completely blocked this process. In control samples, both anti-αX and anti-αM antibodies exerted partial inhibition on monocyte adhesion to fibrinogen as expected. Thus, these findings indicate that monocyte adhesion to Cyr61 is mediated specifically by integrin αMβ2.

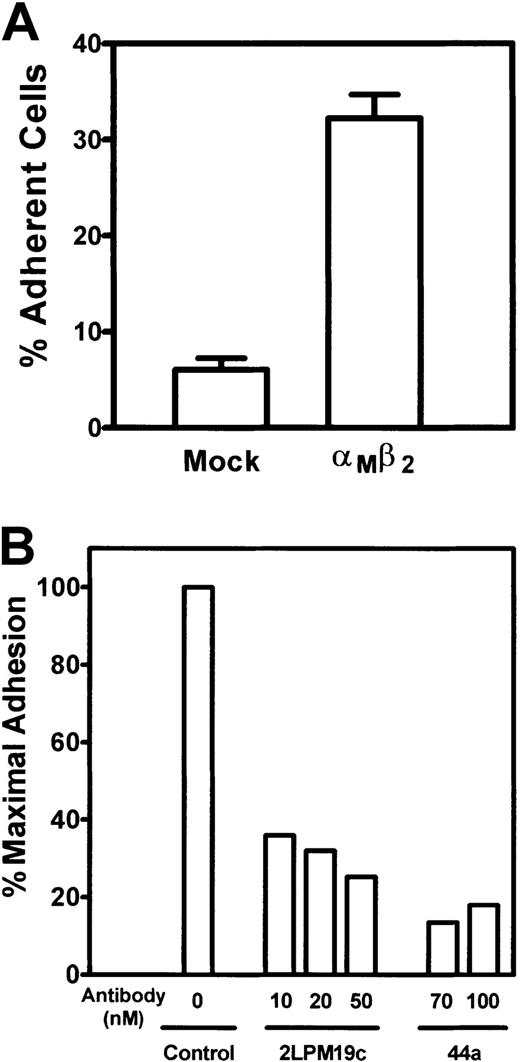

To substantiate the ability of αMβ2 to support cell adhesion, we used human embryonic kidney 293 cells genetically engineered to express the αMβ2integrin. Figure 6A shows that mock-transfected 293 cells adhered poorly to Cyr61; however, the expression of αMβ2 on 293 cells caused an approximate 5-fold enhancement of cell adhesion to Cyr61. The specificity of αMβ2-mediated cell adhesion was further demonstrated by the capacity of 2 anti-αMantibodies, 2LPM19c and 44a, to inhibit the adhesion of αMβ2-expressing 293 cells to Cyr61 (Figure6B).

Adhesion of αMβ2-expressing 293 cells to Cyr61.

(A) 51Cr-labeled αMβ2-expressing or mock-transfected cells were added to microtiter wells coated with 1 μg/mL Cyr61. Cell adhesion proceeded for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by 3 washes to remove nonadherent cells. The adherent cells were solubilized with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 51Cr radioactivity was quantified in a β counter. Data are expressed as a percentage of added cells. (B) 51Cr-labeled αMβ2-expressing 293 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of anti-αM monoclonal antibodies for 15 minutes at 22°C and allowed to adhere to wells coated with 1 μg/mL Cyr61. Data shown are percentages of maximal cell adhesion in a control sample without the antibodies.

Adhesion of αMβ2-expressing 293 cells to Cyr61.

(A) 51Cr-labeled αMβ2-expressing or mock-transfected cells were added to microtiter wells coated with 1 μg/mL Cyr61. Cell adhesion proceeded for 30 minutes at 37°C, followed by 3 washes to remove nonadherent cells. The adherent cells were solubilized with 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 51Cr radioactivity was quantified in a β counter. Data are expressed as a percentage of added cells. (B) 51Cr-labeled αMβ2-expressing 293 cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of anti-αM monoclonal antibodies for 15 minutes at 22°C and allowed to adhere to wells coated with 1 μg/mL Cyr61. Data shown are percentages of maximal cell adhesion in a control sample without the antibodies.

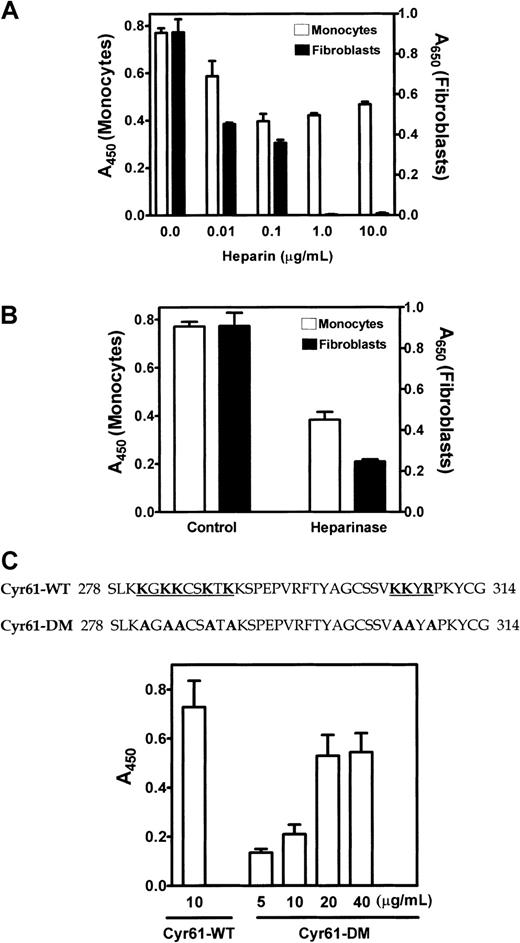

Role of cell surface HSPGs on monocyte adhesion to Cyr61

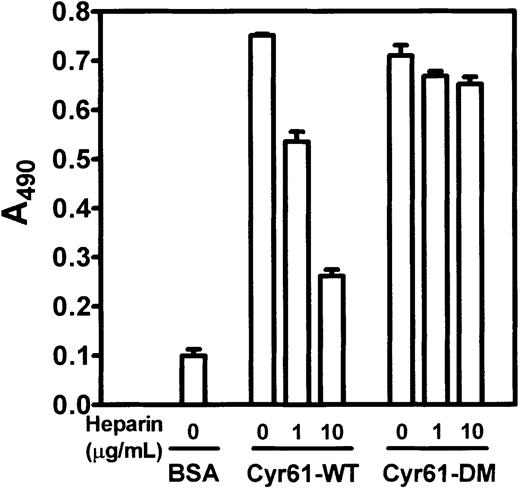

We previously showed that α6β1-mediated fibroblast adhesion to Cyr61 requires cell surface HSPGs to serve as coreceptors.4 In this regard, 2 putative heparin-binding motifs are present in the C-terminal domain of Cyr61 to mediate interaction with cell surface HSPGs. To investigate whether HSPGs on monocytes are also required for cell adhesion to Cyr61, we examined the effect of heparin, which binds Cyr61 with high affinity. As we previously reported,4heparin dose dependently inhibited fibroblast adhesion to Cyr61 and complete inhibition was attained at concentrations of 1 μg/mL or higher (Figure 7A). In parallel samples, we found that heparin also inhibited monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. However, it was much less effective in blocking monocyte adhesion, and only partial inhibition was observed at a heparin concentration as high as 10 μg/mL. When cells were treated with heparinase to remove cell surface HSPGs prior to addition to Cyr61-coated wells, fibroblast adhesion was inhibited by about 75%, whereas monocyte adhesion was reduced by only about 45% (Figure 7B). To further investigate the role of cell surface HSPGs on monocyte adhesion to Cyr61, we examined the ability of monocytes to adhere to Cyr61-DM with alanine substitutions of the basic amino acid residues in both heparin binding motifs of Cyr61 (Figure 7C). Cyr61-DM is deficient in heparin binding and incapable of supporting fibroblast adhesion.4 Figure 7C shows that monocytes adhered to both wild-type Cyr61 and Cyr61-DM, but higher coating concentrations of Cyr61-DM were required for cell adhesion to occur. These results suggest that cell surface HSPGs are also involved in αMβ2-mediated monocyte adhesion to Cyr61; however, the interaction of HSPGs on monocytes with Cyr61 is not absolutely required for this adhesion process.

Role of cell surface HSPGs in monocyte adhesion to Cyr61.

(A) Isolated monocytes (open bars) or 1064SK fibroblasts (closed bars) were preincubated with the indicated concentrations of heparin for 30 minutes at 37°C and added to wells coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61. Cell adhesion proceeded for 20 minutes at 37°C. Adherent monocytes were quantified by measuring A450 in the acid phosphatase assay. Adherent fibroblasts were fixed, stained with 1% methylene blue, and the extracted dye was quantified by measuring A650. (B) Cells were pretreated with or without 2 U/mL heparinase I for 30 minutes at 37°C and allowed to adhere to Cyr61-coated wells for 20 minutes at 37°C. (C) Amino acid sequence of wild-type Cyr61 (Cyr61-WT) at residues 278-314 with the 2 heparin-binding motifs underlined. The Cyr61 mutant protein (Cyr61-DM) contains mutations in both motifs where basic residues were substituted with alanine as shown by the bold letters. ADP-activated monocytes were allowed to adhere to microtiter wells coated with the indicated concentrations of Cyr61-WT or Cyr61-DM. Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figures are representative of 3 experiments.

Role of cell surface HSPGs in monocyte adhesion to Cyr61.

(A) Isolated monocytes (open bars) or 1064SK fibroblasts (closed bars) were preincubated with the indicated concentrations of heparin for 30 minutes at 37°C and added to wells coated with 10 μg/mL Cyr61. Cell adhesion proceeded for 20 minutes at 37°C. Adherent monocytes were quantified by measuring A450 in the acid phosphatase assay. Adherent fibroblasts were fixed, stained with 1% methylene blue, and the extracted dye was quantified by measuring A650. (B) Cells were pretreated with or without 2 U/mL heparinase I for 30 minutes at 37°C and allowed to adhere to Cyr61-coated wells for 20 minutes at 37°C. (C) Amino acid sequence of wild-type Cyr61 (Cyr61-WT) at residues 278-314 with the 2 heparin-binding motifs underlined. The Cyr61 mutant protein (Cyr61-DM) contains mutations in both motifs where basic residues were substituted with alanine as shown by the bold letters. ADP-activated monocytes were allowed to adhere to microtiter wells coated with the indicated concentrations of Cyr61-WT or Cyr61-DM. Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figures are representative of 3 experiments.

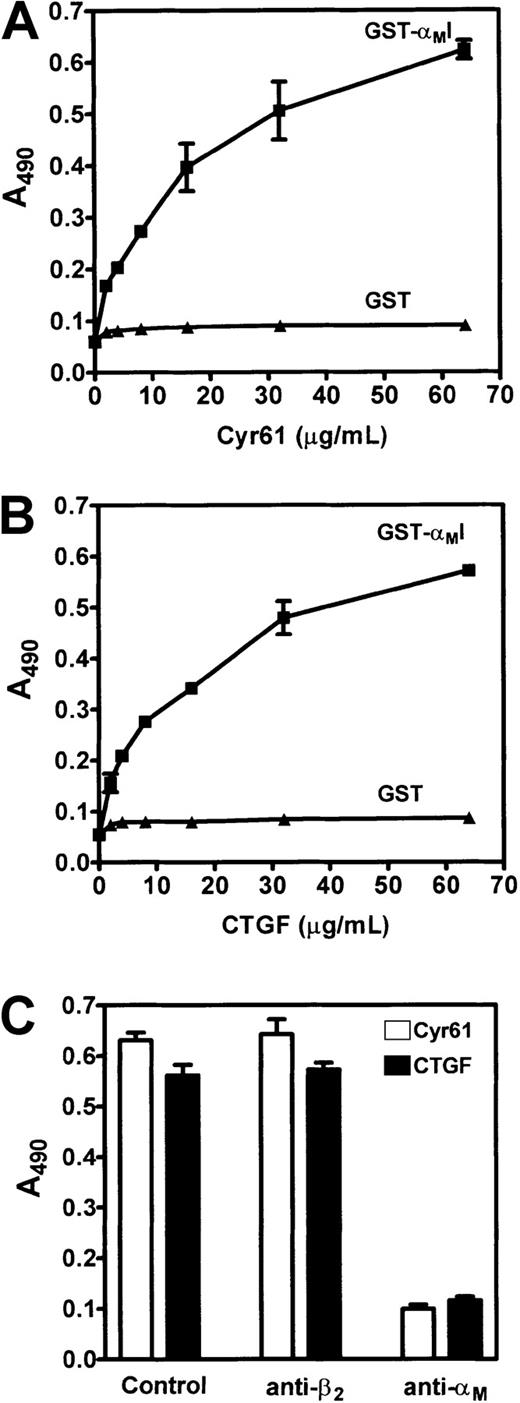

Binding of the I domain of αM to immobilized Cyr61 and CTGF

The cell adhesion data above identify Cyr61 and CTGF as novel adhesive ligands for αMβ2 on monocytes. The integrin αM subunit contains an inserted or I domain that is important for ligand interaction.37 Thus, we examined direct binding of a GST fusion protein containing the I domain of the αM subunit (GST-αMI) to Cyr61 and CTGF in a solid phase binding assay. In these experiments, microtiter wells were coated with Cyr61 or CTGF and the binding of GST-αMI was detected with an anti-GST antibody in an ELISA system. As shown in Figure 8, panels A and B, GST-αMI bound to wells coated with either protein in a dose-dependent and saturable manner. In control samples, GST itself did not bind to either Cyr61- or CTGF-coated wells. To further demonstrate binding specificity, we tested the inhibitory effect of 2LPM19c, a monoclonal antibody directed against the I domain of αM.38 Consistent with the cell adhesion data, preincubation of GST-αMI with 2LPM19c completely inhibited GST-αMI binding to Cyr61- and CTGF-coated wells (Figure 8C). As expected, the anti-β2 antibody (YFC118.3) had no effect on GST-αMI binding even though it blocked monocyte adhesion to both proteins.

Binding of the αMI domain to Cyr61 and CTGF.

Microtiter wells were coated with the indicated concentrations of Cyr61 (A) or CTGF (B), and blocked with 0.15% PVA. GST-αMI fusion protein or GST (1 μM each) was added and allowed to bind for 2 hours at 22°C. After washing, bound GST-αMI or GST was detected using a polyclonal anti-GST antibody followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were detected usingo-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride as the substrate and A490 was measured. (C) GST-αMI was preincubated with vehicle buffer (control), 500 nM YFC118.3 (anti-β2), or 2LPM19c (anti-αM) for 30 minutes at 37°C prior to addition to wells coated with 30 μg/mL Cyr61 (open bars) or CTGF (closed bars). Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs.

Binding of the αMI domain to Cyr61 and CTGF.

Microtiter wells were coated with the indicated concentrations of Cyr61 (A) or CTGF (B), and blocked with 0.15% PVA. GST-αMI fusion protein or GST (1 μM each) was added and allowed to bind for 2 hours at 22°C. After washing, bound GST-αMI or GST was detected using a polyclonal anti-GST antibody followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Bound antibodies were detected usingo-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride as the substrate and A490 was measured. (C) GST-αMI was preincubated with vehicle buffer (control), 500 nM YFC118.3 (anti-β2), or 2LPM19c (anti-αM) for 30 minutes at 37°C prior to addition to wells coated with 30 μg/mL Cyr61 (open bars) or CTGF (closed bars). Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs.

Because heparin caused partial inhibition on monocyte adhesion to Cyr61 (Figure 7A), we examined its inhibitory effect on GST-αMI binding to wild-type Cyr61 and to the heparin binding-deficient Cyr61-DM protein. Figure 9 shows that GST-αMI bound equally well to both wild-type Cyr61 and Cyr61-DM, but not to BSA, indicating that the αMβ2 binding site(s) in Cyr61 is not dependent on the 2 heparin-binding motifs in its C-terminal domain. In the presence of heparin, partial inhibition of GST-αMI binding to wild-type Cyr61, but not to Cyr61-DM, was observed. Thus, heparin binding to wild-type Cyr61 may impose steric hindrance to the αMβ2 binding site(s) in Cyr61. Furthermore, these results eliminate the possibility that heparin exerts its inhibitory effect by binding to the GST-αMI fusion protein.

Binding of GST-αMI to wild-type Cyr61 and Cyr61-DM.

Microtiter wells were coated with 30 μg/mL BSA, Cyr61-WT, or Cyr61-DM, and blocked with 0.15% PVA. GST-αMI (1 μM), preincubated with the indicated concentrations of heparin, was added to the wells and allowed to bind for 2 hours at 22°C. Bound GST-αMI was detected by an ELISA using an anti-GST polyclonal antibody as described in the legend of Figure 8. Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figure is representative of 2 experiments.

Binding of GST-αMI to wild-type Cyr61 and Cyr61-DM.

Microtiter wells were coated with 30 μg/mL BSA, Cyr61-WT, or Cyr61-DM, and blocked with 0.15% PVA. GST-αMI (1 μM), preincubated with the indicated concentrations of heparin, was added to the wells and allowed to bind for 2 hours at 22°C. Bound GST-αMI was detected by an ELISA using an anti-GST polyclonal antibody as described in the legend of Figure 8. Data shown are means of triplicate determinations and error bars represent SEs. Figure is representative of 2 experiments.

Discussion

Cyr61 and CTGF are extracellular matrix–associated signaling molecules that support cell adhesion, promote cell migration, and augment growth factor–induced cell proliferation by interacting with specific integrins on different cell types. In this study, we demonstrated that both Cyr61 and CTGF are expressed in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of apoE−/− mice. Furthermore, we found that THP-1 monocytic cells and peripheral blood monocytes adhere to these proteins in an activation-dependent manner, and identified integrin αMβ2 as the major adhesion receptor mediating monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. In support of these findings, we showed that expression of αMβ2in human embryonic kidney 293 cells resulted in αMβ2-mediated cell adhesion to Cyr61. Additionally, the I domain of αM binds specifically to immobilized Cyr61 and CTGF in a solid phase binding assay. Finally, we found that cell surface HSPGs are also involved in, but not absolutely required for, monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. These observations establish Cyr61 and CTGF as novel adhesive ligands for integrin αMβ2 on activated monocytes and suggest a role for these proteins in the pathophysiologic function of monocytes.

Both Cyr61 and CTGF are expressed in the blood vessels of mice.10,18 Furthermore, in human advanced atherosclerotic lesions, CTGF has been shown to be highly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells as well as in endothelial cells at the luminal sites of the vessels and in the vasa vasorum of the plaque lesions.19 Using the apoE−/− mouse model, we extended these observations and showed that both Cyr61 and CTGF are highly expressed in mouse atherosclerotic lesions. It should be noted that both Cyr61 and CTGF are products of growth factor–inducible immediate-early genes that are rapidly activated on the transcriptional level.7,8 Also, it is well established that the levels of growth factors and cytokines such as platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-β, basic fibroblast growth factor, and interleukin 1β are elevated in atherosclerotic lesions.39 Thus, interaction of these growth regulatory molecules with endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts at the lesion sites would undoubtedly result in the up-regulation of Cyr61 and CTGF expression. Although the functional significance of these proteins in atherosclerosis remains to be determined, their ability to interact with different cell types in the vasculature suggests that they may participate in lesion development as well as the consequences of plaque rupture. In this regard, both Cyr61 and CTGF are angiogenic factors,13,14 and thus they may induce neovascularization in the fibrous plaques. Moreover, we previously demonstrated that activated platelets adhere to Cyr61 and CTGF through integrin αIIbβ3.15 On plaque rupture, the exposure of these proteins in the underlying subendothelial matrix would likely lead to platelet adhesion and the formation of occluding thrombi.

Leukocyte adhesion and migration are essential for their recruitment to atherosclerotic lesions and to areas of extravascular inflammation. These adhesive interactions are mediated primarily by leukocyte-specific β2 integrins.37 Cyr61 and CTGF are expressed in advanced atherosclerotic lesions and in the granulation tissue of the healing cutaneous wounds18,23; therefore, we investigated the interaction of monocytes with these proteins. The results of our studies show that isolated peripheral blood monocytes adhere to Cyr61 following cellular activation with ADP or fMLP. The observation of activation-dependent adhesion, coupled with the divalent cation dependency of this process, suggests the involvement of integrin receptors. Indeed, monoclonal antibodies directed against the αM or β2 subunit specifically blocked monocyte adhesion to Cyr61, indicating that αMβ2 is the major integrin on activated monocytes mediating the adhesion event. Activation of monocytes with fMLP, ADP, and PMA causes a conformational change of αMβ2 through inside-out signaling mechanisms.34,37,40 Our findings that ADP- and fMLP-activated monocytes adhere strongly to Cyr61 as opposed to resting monocytes suggest that activated αMβ2 binds Cyr61 with a higher affinity as compared to the unactivated receptor. An alternative explanation is that activation of monocytes increases cell surface expression of αMβ2, thereby facilitating monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. However, this possibility is unlikely because increased αMβ2 expression is not sufficient to promote αMβ2-dependent cell adhesion to other adhesive ligands such as fibrinogen and intercellular adhesion molecule–1 (ICAM-1).40

All of the α subunits complexed to β2 integrins contain an approximately 200–amino acid insert or I domain in their N-terminal regions.37 Isolated I domains of several α subunits are capable of binding ligands,25,28,41-44 and their atomic resolution structures reveal a unique divalent cation coordination sphere designated the “metal-ion dependent adhesion site.”45 In a solid phase binding assay, we demonstrated that a soluble GST-αMI fusion protein binds specifically to immobilized Cyr61 and CTGF, confirming that these proteins are direct ligands of αMβ2. Unlike the other integrins (ie, αvβ3, αvβ5, αIIbβ3, and α6β1) that have previously been reported to mediate cellular interaction with Cyr61 and CTGF,4,12,15,16 αMβ2 is the first I domain–containing integrin that serves as an adhesion receptor for the CCN family of matrix-associated proteins. At present, the integrin binding site(s) on Cyr61 and CTGF are not known. However, analogous to the findings that αIIbβ3 and αMβ2 binding to different sites on fibrinogen,28,46 47 we speculate that the I domain–containing αMβ2 may bind to a unique site on Cyr61 and CTGF than those recognized by other integrins without the I domain.

Increasing evidence suggests that cell surface HSPGs such as syndecan-4 may act cooperatively with integrins to promote focal adhesion formation.48 Recently, we demonstrated that α6β1-mediated fibroblast adhesion to Cyr61 requires cell surface HSPGs to act as coreceptors for interaction with 2 heparin-binding motifs in the C-terminal domain of Cyr61.4 By contrast, adhesion of endothelial cells to Cyr61 through αvβ3 is independent of the heparin binding activity of Cyr61.4 In the present study, we found that heparin partially blocked monocyte adhesion to Cyr61. Heparin may exert its inhibitory effect by binding to the heparin binding motifs in Cyr61 or by interacting with αMβ2 on monocytes.49 The latter possibility has been excluded by the observation that heparin inhibited the binding of GST-IαM to wild-type Cyr61 but not to the heparin binding-deficient Cyr61-DM protein. Moreover, treatments of monocytes with heparinase I to remove heparan sulfates from the cell surface resulted in partial inhibition of cell adhesion. Together, these findings indicate that HSPGs on monocytes also participate in optimal cell adhesion to Cyr61. Nevertheless, unlike fibroblast adhesion, monocytes are capable of adhering to Cyr61-DM that is deficient of heparin binding activity. Thus, while the binding of cell surface HSPGs to Cyr61 is involved in monocyte adhesion, such interaction is not necessary for this process. The relative affinities of different integrins with Cyr61 may account for the differential requirement of cell surface HSPGs for the adhesion of different cell types to Cyr61.

Although the biologic significance of monocyte interaction with Cyr61 and CTGF remains to be established, the expression of these proteins in plaque lesions and healing wounds suggests that they may play an important role in atherosclerosis and inflammatory responses. In this regard, monocyte adhesion to activated endothelium and their emigration into the extravascular space are important for these processes. It has been reported that CTGF messenger RNA and protein are expressed in endothelial cells at the luminal site of atherosclerotic plaques,19 and therefore, it may act in concert with other adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 to mediate monocyte adhesion through αMβ2. Both Cyr61 and CTGF have been reported to stimulate cell migration through integrins,13,14,16 and it is likely that they would also induce transendothelial migration of monocytes. Once migrated, monocytes differentiate into macrophages; whether Cyr61 and CTGF play a regulatory role in this process is an intriguing possibility. Finally, these proteins are ligands of αMβ2 on monocytes and would likely induce integrin-dependent outside-in signaling as has recently been shown in fibroblasts.50 In monocytes, integrin signaling leads to the expression of proinflammatory and proatherosclerotic substances such as interleukin 1β.51 Based on these considerations, the potential role of CTGF and Cyr61, and perhaps other members of the CCN family, in the pathophysiologic function of monocytes merits further investigation.

Supported by grants HL-41793 (S.C.-T.L.), CA-46565 and CA-80080 (L.F.L.), and HL-63199 (T.P.U.) from the National Institutes of Health. J.M.S. has been supported by the National Institutes of Health HL-07829 training grant and by a predoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliate. Presented in part at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, December 1-5, 2000, San Francisco, CA.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Stephen C.-T. Lam, Department of Pharmacology (M/C 868), University of Illinois at Chicago, 835 S Wolcott Ave, Chicago, IL 60612; e-mail: sclam@uic.edu.