Fanconi anemia (FA) is a human autosomal recessive cancer susceptibility disorder characterized by cellular sensitivity to mitomycin C and defective cell-cycle progression. Six FA genes (corresponding to subtypes A, C, D2, E, F, and G) have been cloned, and the encoded FA proteins interact in a common pathway. DNA damage activates this pathway, leading to monoubiquitination of the downstream FANCD2 protein and targeting to nuclear foci containing BRCA1. In the current study, we demonstrate that FANCD2 also undergoes monoubiquitination during S phase of the cell cycle. Monoubiquitinated FANCD2 colocalizes with BRCA1 and RAD51 in S-phase–specific nuclear foci. Monoubiquitination of FANCD2 is required for normal cell-cycle progression following cellular exposure to mitomycin C. Our data indicate that the monoubiquitination of FANCD2 is highly regulated, and they suggest that FANCD2/BRCA1 complexes and FANCD2/RAD51 complexes participate in an S-phase–specific cellular process, such as DNA repair by homologous recombination.

Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA) is an autosomal recessive cancer susceptibility syndrome characterized by multiple congenital anomalies and progressive bone marrow failure.1,2 FA cells are sensitive to DNA cross-linking agents, such as mitomycin C (MMC) and, to a lesser extent, ionizing radiation (IR).3,4 Based on somatic cell fusion studies, FA is composed of 8 distinct complementation groups (A, B, C, D1, D2, E, F, and G).5,6 Six of the FA genes—FANCA, FANCC, FANCD2, FANCE, FANCF, and FANCG—have been cloned.6-12

Recent studies have demonstrated that the 6 cloned FA proteins interact in a common cellular pathway.13 The FANCA, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, and FANCG proteins assemble in a multisubunit nuclear complex.14,15 This FA protein complex is required for the monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 protein, suggesting that the complex functions as a multisubunit monoubiquitin ligase or regulates such an activity. When normal (non-FA) cells are exposed to DNA-damaging agents, FANCD2 is monoubiquitinated and targeted to nuclear foci containing BRCA1.13 Disruption of this pathway leads to the characteristic cellular and clinical abnormalities observed in FA.

FA cells have a defect in cell-cycle progression. First, FA cells lack the ability to delay S-phase progression in response to DNA damage from DNA cross-linking agents.16,17 Second, FA cells accumulate in the G2 phase of the cell cycle following cross-linker exposure.18 This G2 delay appears to result from a normal G2/M checkpoint response to excessive DNA damage in the preceding S phase.19 Third, recent studies demonstrate that FA cells arrest in late S phase following cellular exposure to interstrand cross-links (ICLs), suggesting that the FA pathway helps to repair these cross-links in S phase.20 21

The recently demonstrated interaction between FANCD2 and BRCA113 has suggested possible cellular functions of the FA pathway. BRCA1(−/−) cells are phenotypically similar to FA cells, displaying spontaneous chromosome breakage and MMC or IR sensitivity.22 BRCA1(−/−) cells have a defect in an S-phase cell-cycle checkpoint after IR23 and have a defect in homology-directed DNA repair (HDR).22 24 These results suggest that the FA pathway regulates an S-phase checkpoint response, a DNA repair response, or both.

In the current study, we examined the FANCD2 protein during the cell cycle. We found that FANCD2 is monoubiquitinated during the S phase of the cell cycle and that FANCD2/BRCA1 foci and FANCD2/RAD51 foci form during S phase. The monoubiquitination of FANCD2 during S phase is required for normal cell-cycle progression following cellular exposure to MMC.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The simian virus 40 (SV40)–transformed FA fibroblasts GM6914 (FA-A) and PD20 (FA-D2), as well as HeLa cells, were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 15% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). GM6914 cells were functionally complemented with pMMP retroviral vectors containing FANCA cDNA, and functional complementation was confirmed by the MMC assay.25 Stable FA-D2 transfectants (PD20) expressing wild-type FANCD2 or the FANCD2(K561R) mutant were previously described.13

Retroviral infection and MMC sensitivity assay

The retroviral expression vectors pMMP-puro,26pMMP-puro FANCD2, and pMMP-puro FANCD2K561R13 were described previously. pMMP-puro-HA-FANCD2(wt) was generated by adding the influenza hemagglutinin (HA) tag (AYPYDVPDYA) at the amino terminus of FANCD2. Production of pMMP retroviral supernatants and infection of fibroblasts were performed as previously described.25After 48 hours, cells were trypsinized and selected in medium containing puromycin (1 μg/mL). Cells were analyzed for MMC sensitivity by the crystal violet assay.25

Cell-cycle synchronization

HeLa cells or the indicated FA fibroblast lines were synchronized by the double-thymidine–block method as previously described, with minor modifications.27 Briefly, cells were treated with 2 mM thymidine for 18 hours, thymidine-free media for 10 hours, and 2 mM thymidine for 18 hours to arrest the cell cycle at the G1/S boundary. Cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then released in DMEM + 15% FCS and analyzed at various time intervals. Alternatively, HeLa cells were treated with 0.5 mM mimosine (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 24 hours for synchronization in late G1 phase,28 washed twice with PBS, and released into DMEM + 15% FCS. For synchronization in M phase, a nocodazole block was used.29Cells were treated with 0.1 μg/mL nocodazole (Sigma) for 15 hours, and the nonadherent cells were washed twice with PBS and replated in DMEM + 15% FCS.

Cell-cycle analysis

Trypsinized cells were resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS and fixed by adding 5 mL ice-cold ethanol. Cells were next washed twice with PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) fraction V (1% BSA/PBS; Sigma) and were resuspended in 0.24 mL of 1% BSA/PBS. After adding 30 μL of 500 μg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma) in 38 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.0) and 30 μL of 10 mg/mL DNase-free RNase A (Sigma), samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. DNA content was measured by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed by the CellQuest and Modfit LT programs (Becton Dickinson).

Determination of the G2 to M cell-cycle transition

PD20 cell lines were synchronized at the G1/S interface as described above, except that 10 mM thymidine treatment was used. Treatment with 500 nM (167 ng/mL) MMC was from 1 to 3 hours following release from the second thymidine block. At the indicated time points, cells were collected by trypsinization, pooled with nonattached cells, and fixed for a minimum of 10 minutes with 90% methanol/PBS at −20°C. Cells were then washed with PBS, incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with a 200-fold dilution of MPM-2 antibody (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) in antibody buffer (PBS containing 3% BSA, 0.05% Tween-20, and 0.04% sodium azide). Cells were washed once with PBS and were incubated with a 500-fold dilution of fluorescein-conjugated antimouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibodies in antibody buffer for 30 minutes at 37°C. Cells were washed once with PBS and then were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C in 4 mM sodium citrate (pH 7.8), 1% triton X-100, 30 U/mL DNase-free RNase A, and 50 mg/mL propidium iodide. Following the addition of NaCl to 138 mM, cells were kept on ice until analyzed with a FACScan system using Cell Quest Software (Becton Dickinson). Cell aggregates were gated out, and 10 000 events were analyzed.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed as previously described.13 Anti-FANCD2 mouse monoclonal antibody FI17 (1:200 dilution) was used as a primary antibody.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes, followed by permeabilization with 0.3% Triton-X-100 in PBS (10 minutes). After blocking in 10% goat serum and 0.1% NP-40 in PBS (blocking buffer), specific antibodies were added at the appropriate dilution in blocking buffer and were incubated for 2 to 4 hours at room temperature. FANCD2 was detected using the affinity-purified E35 polyclonal antibody (1/100).13 For BRCA1 detection, we used a commercial monoclonal antibody (D-9; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) at 2 μg/mL. For HA detection, anti-HA (HA.11; Babco, Richmond, CA) (1:500) antibody was used. Alternatively, the polyclonal anti-RAD51 antibody (Oncogene, Boston, MA; Ab-1, 1:800) was used. Cells were subsequently washed 3 times in PBS + 0.1% NP-40 (10-15 minutes each wash), and species-specific fluorescein or Texas red-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) were diluted in blocking buffer (antimouse 1/700, antirabbit 1/700) and added. After 1 hour at room temperature, 3 more 10- to 15-minute washes containing 1 μg/mL DAPI were applied, and the slides were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were captured on a Nikon microscope and processed using Openlab (Improvision, Lexington, MA) and Adobe Photoshop software. Colocalization of FANCD2 and BRCA1 was performed as previously described.13

Results

FANCD2 is monoubiquitinated during S phase

We initially examined the activation of the FA pathway during normal cell-cycle progression in the absence of DNA-damaging agents (Figure 1). HeLa cells were synchronized at the G1/S boundary by double-thymidine block, released into S phase, and analyzed for the presence of FANCD2 by immunoblotting (Figure 1A). FANCD2-L (monoubiquitinated isoform) was detected specifically at the G1/S boundary and throughout the S phase. S-phase detection of FANCD2-L was confirmed when HeLa cells were synchronized by other methods, such as nocodazole arrest (Figure 1B) or mimosine block (Figure 1C). Cells arrested in mitosis did not display FANCD2-L, suggesting that FANCD2-L is deubiquitinated or degraded before cell division (Figure 1A, 10 hours). These results demonstrate that FANCD2 monoubiquitination is highly regulated during the cell cycle.

S-phase–specific monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 protein.

(A) HeLa cells were synchronized by the double-thymidine–block method. Cells corresponding to the indicated phase of the cell cycle, as determined by flow cytometric analysis of DNA content, were lysed and processed for FANCD2 immunoblotting. FANCD2-L is the monoubiquitinated isoform, and FANCD2-S is an unubiquitinated isoform. Immunoblots of FANCD2 during cell-cycle progression were also analyzed following synchronization by either nocodazole block (B) or mimosine block (C). (D) HeLa cells were blocked in M phase using nocodazole and subsequently released into drug-free medium to allow cell-cycle progression. At the indicated times following release (corresponding to the indicated phase of the cell cycle), cells were fixed, immunostained with anti-FANCD2 antibody, and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. (E) Analysis of FANCD2 immunolocalization in HeLa cells synchronized with mimosine. Original magnification, × 600.

S-phase–specific monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 protein.

(A) HeLa cells were synchronized by the double-thymidine–block method. Cells corresponding to the indicated phase of the cell cycle, as determined by flow cytometric analysis of DNA content, were lysed and processed for FANCD2 immunoblotting. FANCD2-L is the monoubiquitinated isoform, and FANCD2-S is an unubiquitinated isoform. Immunoblots of FANCD2 during cell-cycle progression were also analyzed following synchronization by either nocodazole block (B) or mimosine block (C). (D) HeLa cells were blocked in M phase using nocodazole and subsequently released into drug-free medium to allow cell-cycle progression. At the indicated times following release (corresponding to the indicated phase of the cell cycle), cells were fixed, immunostained with anti-FANCD2 antibody, and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. (E) Analysis of FANCD2 immunolocalization in HeLa cells synchronized with mimosine. Original magnification, × 600.

We next demonstrated that the cell-cycle–dependent monoubiquitination of FANCD2 correlated with the formation of FANCD2 nuclear foci (Figure1D). Nocodazole arrested (mitotic) cells exhibited no FANCD2 foci (Figure 1D, panel ii). During G1 phase (6 hours after release from synchronization with nocodazole), only FANCD2-S was detected by immunoblotting, and this protein was distributed in a diffuse nuclear pattern (Figure 1D, panel iii). When the synchronized cells entered S phase (15 to 18 hours), an increase in FANCD2-L and FANCD2 nuclear foci was observed (Figure 1D, panels vi,vii). A similar result was observed in mimosine-synchronized cells (Figure1E).

We have previously shown that FA cells from complementation groups A, C, F, and G fail to assemble the FA protein complex and fail to monoubiquitinate FANCD2 in response to DNA damage.13 We examined the expression of the FANCD2 isoforms in FA cells and functionally complemented FA cells during the cell cycle (Figure2). FA-A cells showed normal levels of FANCD2-S throughout the cell cycle but failed to display monoubiquitinated FANCD2-L at any point during the cell cycle (Figure2A). Functional complementation of these cells by stable transfection with the FANCA cDNA restored MMC resistance25 and restored the S-phase–specific expression of FANCD2-L. Similar results were obtained when the FA-A and corrected FA-A cells were synchronized with nocodazole (Figure 2B).

Fanconi anemia (subtype A) cells are defective in the monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 protein during S phase.

SV40-transformed fibroblasts from an FA-A patient (GM6914) and GM6914 cells corrected with FANCA cDNA were compared. Cells were synchronized by either the double-thymidine–block method (A) or the nocodazole block method (B). FANCD2 was examined by anti-FANCD2 immunoblotting.

Fanconi anemia (subtype A) cells are defective in the monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 protein during S phase.

SV40-transformed fibroblasts from an FA-A patient (GM6914) and GM6914 cells corrected with FANCA cDNA were compared. Cells were synchronized by either the double-thymidine–block method (A) or the nocodazole block method (B). FANCD2 was examined by anti-FANCD2 immunoblotting.

Monoubiquitination of FANCD2 at K561 during S phase is required for normal cell-cycle progression

We next examined whether the S-phase–dependent expression of FANCD2-L results from monoubiquitination at lysine 561 (Lys561) (Figure3). FA-D2 (PD20) fibroblasts, devoid of FANCD2 protein, were stably transduced with the cDNA encoding either FANCD2 (wt) or FANCD2 (K561R). Expression of wild-type FANCD2, but not FANCD2 (K561R), corrected the MMC sensitivity of the FA-D2 cells, as previously described (data not shown).13 The corrected cells demonstrated S-phase–specific monoubiquitination of FANCD2 (Figure 3A). In contrast, FANCD2 (K561R) was not monoubiquitinated during the cell cycle.

Monoubiquitination of FANCD2 at Lys561 during S phase is required for normal cell-cycle progression.

(A) PD20 (FA-D2) fibroblasts were transduced with pMMP-FANCD2 (wt), pMMP-FANCD2 (K561R), or pMMP (empty vector), and stably transduced cells were selected in puromycin. Indicated cells were synchronized by double-thymidine block, and whole-cell lysates from the indicated cell-cycle stages were immunoblotted with the anti-FANCD2 monoclonal antibody. (B) Indicated transfectants were synchronized at the G1/S boundary by double-thymidine block and synchronously released into S phase. Where indicated, the cells were exposed to MMC (500 nM) for 2 hours, at 1 to 3 hours after release, followed by the removal of MMC and the addition of fresh medium. Progression of the indicated cell lines from G2 to M phase was determined by quantitating the percentage of cells with an elevated FACS signal with the MPM-2 antibody, as previously described.30 31

Monoubiquitination of FANCD2 at Lys561 during S phase is required for normal cell-cycle progression.

(A) PD20 (FA-D2) fibroblasts were transduced with pMMP-FANCD2 (wt), pMMP-FANCD2 (K561R), or pMMP (empty vector), and stably transduced cells were selected in puromycin. Indicated cells were synchronized by double-thymidine block, and whole-cell lysates from the indicated cell-cycle stages were immunoblotted with the anti-FANCD2 monoclonal antibody. (B) Indicated transfectants were synchronized at the G1/S boundary by double-thymidine block and synchronously released into S phase. Where indicated, the cells were exposed to MMC (500 nM) for 2 hours, at 1 to 3 hours after release, followed by the removal of MMC and the addition of fresh medium. Progression of the indicated cell lines from G2 to M phase was determined by quantitating the percentage of cells with an elevated FACS signal with the MPM-2 antibody, as previously described.30 31

We next analyzed cell-cycle progression in the various transfected FA-D2 fibroblast lines (Table 1 and Figure 3B). Double-thymidine–blocked cells were released into S phase, either in the absence or presence of the DNA cross-linking agent MMC, and were analyzed for cell-cycle progression. By 3 hours following release, cells had advanced into S phase to more than 85%, irrespective of MMC exposure. Uncorrected FA-D2 cells (ie, transduced with empty vector or with the cDNA-encoding FANCD2 [K561R]) and corrected FA cells (ie, transduced with the wild-type FANCD2 cDNA) showed no difference in S-phase duration (Table 1). More than 77% of the synchronized cells had traversed S phase and entered G2/M phase after 8 hours. Exposure to MMC had no obvious effect on S-phase duration (8 hours). By 12 hours following release from double-thymidine block, in the absence of MMC, many corrected and uncorrected PD20 cells had completed cell division as determined by the reappearance of a G1 peak. However, MMC-exposed cells retained a 4 N DNA content longer and failed to progress to the G1 phase of the next cell cycle.

Cell-cycle progression of FA-D2 transfectants

| Treatment . | Time after release (h) . | PD20-FANCD2 (wt) . | PD20-FANCD2 (K561R) . | PD20-pMMP . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 . | S . | G2/M . | G1 . | S . | G2/M . | G1 . | S . | G2/M . | ||

| −MMC | 0 | 83.7 | 12.4 | 3.9 | 79.1 | 16.0 | 4.9 | 81.4 | 12.8 | 5.8 |

| 3 | 2.9 | 86.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 94.2 | 5.8 | 9.8 | 87.3 | 2.9 | |

| 8 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 82.0 | 2.6 | 18.3 | 79.1 | 5.1 | 10.1 | 84.8 | |

| 12 | 42.3 | 10.1 | 47.6 | 45.4 | 8.4 | 46.2 | 45.6 | 11.1 | 43.3 | |

| +MMC | 0 | 79.2 | 18.7 | 2.1 | 81.9 | 14.7 | 3.4 | 80.6 | 14.9 | 4.5 |

| 3 | 1.7 | 87.0 | 11.3 | 9.7 | 85.7 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 88.0 | 9.7 | |

| 8 | 2.2 | 16.1 | 81.7 | 2.1 | 20.1 | 77.8 | 2.5 | 20.4 | 77.1 | |

| 12 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 83.2 | 2.9 | 9.1 | 88.1 | 3.8 | 9.0 | 87.2 | |

| Treatment . | Time after release (h) . | PD20-FANCD2 (wt) . | PD20-FANCD2 (K561R) . | PD20-pMMP . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 . | S . | G2/M . | G1 . | S . | G2/M . | G1 . | S . | G2/M . | ||

| −MMC | 0 | 83.7 | 12.4 | 3.9 | 79.1 | 16.0 | 4.9 | 81.4 | 12.8 | 5.8 |

| 3 | 2.9 | 86.0 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 94.2 | 5.8 | 9.8 | 87.3 | 2.9 | |

| 8 | 2.0 | 16.0 | 82.0 | 2.6 | 18.3 | 79.1 | 5.1 | 10.1 | 84.8 | |

| 12 | 42.3 | 10.1 | 47.6 | 45.4 | 8.4 | 46.2 | 45.6 | 11.1 | 43.3 | |

| +MMC | 0 | 79.2 | 18.7 | 2.1 | 81.9 | 14.7 | 3.4 | 80.6 | 14.9 | 4.5 |

| 3 | 1.7 | 87.0 | 11.3 | 9.7 | 85.7 | 4.6 | 2.3 | 88.0 | 9.7 | |

| 8 | 2.2 | 16.1 | 81.7 | 2.1 | 20.1 | 77.8 | 2.5 | 20.4 | 77.1 | |

| 12 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 83.2 | 2.9 | 9.1 | 88.1 | 3.8 | 9.0 | 87.2 | |

Indicated PD20 (FA-D2) fibroblast transfectants were arrested at G1/S using double-thymidine block and were released into S phase.

Cell-cycle progression was analyzed by DNA flow histograms of propidium iodide–stained cells.

To determine whether the 4 N arrest following MMC occurred in G2 versus M phase, we used a biparameter flow cytometric assay with MPM-2 antibody (specific for mitotic-phosphorylated protein) and DNA content (Figure 3B).30 31 Cells with 4 N DNA content and high expression of MPM-2 were scored as mitotic cells. In the absence of MMC-induced DNA damage, there was no significant difference in the progression of corrected or uncorrected FA cells from G2 to M phase. The peak in mitosis occurred at 10 to 12 hours after release from G1/S block. In the presence of MMC-induced DNA damage, entry into mitosis was strongly suppressed in FANCD2 (wt)-corrected FA-D2 cells. Mitotic entry in uncorrected (empty vector-transfected or FANCD2 [K561R]-transfected) cells was strongly suppressed, with the peak of mitosis occurring more than 15 hours after release from G1/S. Taken together, these results demonstrate that uncorrected FA cells have a prolonged G2to M transit time following cross-linker exposure.

BRCA1 colocalizes with FANCD2 during S phase

Because FANCD2 colocalizes with BRCA1 following DNA damage, we next tested whether FANCD2 colocalizes with BRCA1 during S phase in the absence of DNA-damaging agents (Figure4). HeLa cells were synchronized with mimosine, released into S phase, and costained with antisera to FANCD2 and BRCA1. As shown in Figure 4A, during S phase most (70%) FANCD2 foci overlapped with BRCA1 foci.

Colocalization of activated FANCD2 and BRCA1 in discrete nuclear foci during S phase.

(A) HeLa cells were synchronized at G1/S with mimosine and released into S phase. S-phase cells were double-stained with the monoclonal anti-BRCA1 antibody D-9 (green; i,iv) and the rabbit polyclonal anti-FANCD2 antibody (red; ii,v), and stained cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Where green and red signals overlap, a yellow pattern is seen, indicating colocalization of BRCA1 and FANCD2 (iii,vi). (B) Differential effect of DNA damage on BRCA1 foci and FANCD2 foci during S phase. HeLa cells were synchronized with mimosine and released into S phase. Enriched S-phase–synchronized cell populations were analyzed by DNA flow histograms to ensure cell synchrony (data not shown). S-phase cells were untreated or were exposed to IR (5 Gy), MMC (20 ng/mL), or UV (50 J/m2) as indicated. One hour after treatment, cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies to FANCD2 and BRCA1. Original magnification, × 600.

Colocalization of activated FANCD2 and BRCA1 in discrete nuclear foci during S phase.

(A) HeLa cells were synchronized at G1/S with mimosine and released into S phase. S-phase cells were double-stained with the monoclonal anti-BRCA1 antibody D-9 (green; i,iv) and the rabbit polyclonal anti-FANCD2 antibody (red; ii,v), and stained cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Where green and red signals overlap, a yellow pattern is seen, indicating colocalization of BRCA1 and FANCD2 (iii,vi). (B) Differential effect of DNA damage on BRCA1 foci and FANCD2 foci during S phase. HeLa cells were synchronized with mimosine and released into S phase. Enriched S-phase–synchronized cell populations were analyzed by DNA flow histograms to ensure cell synchrony (data not shown). S-phase cells were untreated or were exposed to IR (5 Gy), MMC (20 ng/mL), or UV (50 J/m2) as indicated. One hour after treatment, cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies to FANCD2 and BRCA1. Original magnification, × 600.

We examined the dynamic behavior of FANCD2 and BRCA1 foci in S phase following DNA damage (Figure 4B). Treatment of S-phase–synchronized cells with IR, MMC, or UV resulted in a rapid diffusion of BRCA1 dots, as previously described.32,33 FANCD2 dots did not disperse following DNA damage, suggesting that BRCA1 and FANCD2 proteins transiently dissociate in response to DNA damage. The FANCD2 protein is therefore similar to other BRCA1-associated proteins, such as hCds1/Chk233 and CtIP,34 which transiently dissociate from BRCA1 foci following IR-activated BRCA1 phosphorylation in S phase.

Interaction of FANCD2 and RAD51 during S phase

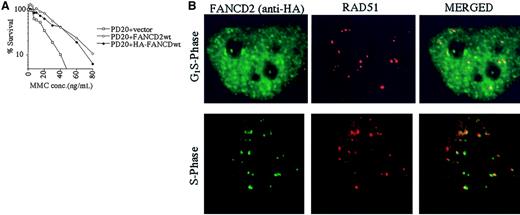

The RecA homologue, RAD51, binds single-stranded DNA and, together with BRCA2, is required for homology-directed DNA repair.35 RAD51 forms nuclear foci during S phase in untreated cells and colocalizes with BRCA1 in ionizing-radiation–inducible foci and in S-phase foci.36We therefore determined whether the activated (monoubiquitinated) FANCD2 protein colocalizes with RAD51 by performing double immunolabeling in complemented FANCD2 cells (Figure5). PD20 (FA-D2) fibroblasts cells were stably transfected and complemented with an amino terminal epitope (HA)-tagged form of FANCD2 (Figure 5A). Immunofluorescence revealed that the HA-FANCD2 colocalizes with endogenous RAD51 during S phase (Figure 5B). The interaction of FANCD2 and RAD51 further supports a model in which FANCD2 functions in homologous recombination repair during S phase.

Interaction of FANCD2 and RAD51 during S phase.

PD20 (FA-D2) cells were stably transfected with the cDNA encoding the amino terminal HA-epitope–tagged version of FANCD2. (A) Cells were examined for MMC sensitivity. (B) Cells were synchronized by the double-thymidine–block method, and synchrony was confirmed by FACS analysis (data not shown). Double-label immunofluorescence (IF) was performed with a murine monoclonal antibody to HA (HA.11; green) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody to RAD51 (Ab-1; red). Where green and red signals overlap, a yellow pattern is seen, indicating colocalization of FANCD2 and RAD51. Original magnification, × 600.

Interaction of FANCD2 and RAD51 during S phase.

PD20 (FA-D2) cells were stably transfected with the cDNA encoding the amino terminal HA-epitope–tagged version of FANCD2. (A) Cells were examined for MMC sensitivity. (B) Cells were synchronized by the double-thymidine–block method, and synchrony was confirmed by FACS analysis (data not shown). Double-label immunofluorescence (IF) was performed with a murine monoclonal antibody to HA (HA.11; green) and a rabbit polyclonal antibody to RAD51 (Ab-1; red). Where green and red signals overlap, a yellow pattern is seen, indicating colocalization of FANCD2 and RAD51. Original magnification, × 600.

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrate that the FA pathway is activated during S phase of the normal cell cycle. Like DNA damage-inducible monoubiquitination, the S-phase–specific monoubiquitination of FANCD2 is dependent on the presence of an intact FA protein complex. FANCD2 monoubiquitination is required for normal cell-cycle progression following DNA damage. FA-D2 cells and corrected FA-D2 cells traverse S phase with similar kinetics. If the cells are exposed to DNA cross-linkers during S phase, however, the mutant (noncorrected) cells fail to progress from G2 to M. The monoubiquitination of FANCD2 during S phase is required for the normal completion of the subsequent phases of the cell cycle.

Regulation of S-phase–specific monoubiquitination

The molecular events that regulate the S-phase–specific monoubiquitination of FANCD2 are unknown, and several models are possible. First, the FA protein complex may become an active monoubiquitin ligase during S phase. For instance, a protein subunit of the complex may become activated by phosphorylation during S phase. Alternatively, the FA complex may assemble or may acquire new active subunits during S phase, resulting in its activation. At least one subunit (FANCG) of the FA protein complex is cyclically phosphorylated in mitosis,37 suggesting a possible mechanism of cell-cycle–dependent modulation of enzyme activity. Second, the FANCD2 protein may become phosphorylated during S phase, rendering it a suitable substrate for monoubiquitination. Consistent with this latter model, the FANCD2 protein is a phosphoprotein, though its specific kinase(s) remain unknown (data not shown).

S-phase–specific monoubiquitination and DNA damage-inducible monoubiquitination of FANCD2 appear to be mechanistically distinct. For instance, DNA damage activates FANCD2 monoubiquitination and FANCD2 foci formation even during the G1 phase of the cell cycle (I.G.-H., unpublished observation, December 2000). Perhaps different upstream kinases activate S-phase– or DNA-damage–inducible monoubiquitination. Like FANCD2, BRCA1 is phosphorylated in S phase or following cellular exposure to DNA damage. Cyclin A/cdk2 activates cell-cycle–dependent phosphorylation of BRCA1,29 and ATM, ATR, and CHK2 activate the DNA damage-inducible phosphorylation of BRCA1.33,38-40 Phosphorylation of BRCA1, resulting from IR induction or S-phase progression, may enhance ubiquitin ligase activity and monoubiquitination of FANCD2. Consistent with this model, recent studies have shown that ATM-dependent phosphorylation of another ubiquitin ligase, MDM2, may regulate its ability to ubiquitinate p53.41

As cells enter G2/M, the monoubiquitinated FANCD2-L isoform is no longer detected, suggesting that it is either deubiquitinated or degraded at this stage of the cell cycle. Deubiquitination is more likely than degradation, because there is no obvious change in the steady state level of FANCD2 protein during cell-cycle progression and the protein half-life of the wild-type and K561R (unubiquitinated) FANCD2 polypeptides are similar (data not shown). Identification of the deubiquitinating enzyme, which converts FANCD2-L to FANCD2-S, may reveal an important level of regulation of the FA pathway.

Possible functional roles of FANCD2/BRCA1 foci and FANCD2/RAD51 foci in S phase

Recent studies have demonstrated that the BRCA1 protein is required for HDR.22,24 One type of HDR (ie, gene conversion by sister chromatids) can occur during S phase of the cell cycle.42,43 Gene conversion occurs during normal DNA replication42 and may function to repair replication intermediates (ie, double-strand breaks) that occur normally during S phase. HDR is an error-free mechanism of DNA repair, requires DNA replication and strand invasion by a sister chromatid, and requires RAD51. Consistent with a direct role in homologous recombination, BRCA1 forms foci with RAD51 during normal S phase.36

Several lines of evidence support the notion that FANCD2 interacts with BRCA1 and RAD51 in an S-phase DNA repair or checkpoint response. First, BRCA1 protein and FANCD2 protein are not expressed in G0 (resting) cells, and levels are induced following cell stimulation with serum (data not shown). Second, BRCA1 is phosphorylated during S phase and forms foci in S phase, consistent with a specific S-phase function.32 Third, recent studies have shown that BRCA1(−/−) cells have an S-phase checkpoint defect.23

Because FANCD2 interacts with BRCA1 and RAD51 during S phase and because cellular deficiency of either FANCD2 or BRCA1 results in severe MMC sensitivity, disruption of the FA pathway may also disrupt HDR activity. We are currently testing this hypothesis. In a normal cell, the FA pathway may function by regulating the magnitude or fidelity of DNA repair by homologous recombination. Finally, an understanding of the precise role of activated FANCD2 in DNA repair may require the identification of other FANCD2-binding proteins or the establishment of in vitro models of repair by homologous recombination.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 28, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0278.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1HL52725-04, RO1DK43889-09, PO1HL54785-04, PO1DK5654 (A.D.D.), and F32-CA88445-01 (R.C.G.) and by a grant from the Naito Foundation (T.T.). I.G.-H. and P.R.A. are Special Fellows of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Alan D. D'Andrea, Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Medical School, 44 Binney St, Boston, MA 02115; e-mail:alan_dandrea@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal