The human blood group i and I antigens are determined by linear and branched poly-N-acetyllactosamine structures, respectively. In erythrocytes, the fetal i antigen is converted to the adult I antigen by I-branching β-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (IGnT) during development. Dysfunction of the I-branching enzyme may result in the adult i phenotype in erythrocytes. However, the I gene responsible for blood group I antigen has not been fully confirmed. We report here a novel human I-branching enzyme, designatedIGnT3. The genes for IGnT1 (reported in 1993),IGnT2 (also presented in this study), and IGnT3consist of 3 exons and share the second and third exons. Bone marrow cells preferentially expressed IGnT3 transcript. During erythroid differentiation using CD34+ cells,IGnT3 was markedly up-regulated with concomitant decrease in IGnT1/2. Moreover, reticulocytes expressed theIGnT3 transcript, but IGnT1/2 was below detectable levels. By molecular genetic analyses of an adult i pedigree, individuals with the adult i phenotype were revealed to have heterozygous alleles with mutations in exon 2 (1006G>A; Gly336Arg) and exon 3 (1049G>A; Gly350Glu), respectively, of the IGnT3gene. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with each mutatedIGnT3 cDNA failed to express I antigen. These findings indicate that the expression of the blood group I antigen in erythrocytes is determined by a novel IGnT3, not byIGnT1 or IGnT2.

Introduction

The blood group I and i antigens (I/i antigens) were first detected by cold agglutinating autoantibodies, and they display a dramatic change during human development.1-4Fetal and neonatal red blood cells (RBCs) contain i antigen but little I antigen, whereas I antigen expression gradually increases as the i antigen decreases after birth. RBCs from most adults and children 18 months or older exhibit I antigen and contain little i antigen.3,4 Thus, the I/i antigens on RBCs exhibit a reciprocal expression profile during development. The I/i antigens are also present on the cell surface in various tissues and body fluids,5,6 and they are recognized as histo-blood group antigens.7

I/i antigens are defined as carbohydrate structures on glycoproteins8 and glycolipids.9 The i antigen epitope is a linear poly-N-acetyllactosamine chain that has Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3 unit repeats, whereas the I antigen structure contains branched poly-N-acetyllactosaminoglycans (Figure 1).9 10 The other blood group ABH and Lewis antigen determinants are expressed at the termini of carbohydrate chains with the internal I/i antigen structures. The I-branched carbohydrates may play important roles in cell–cell interactions during development, differentiation, and oncogenesis, especially by presenting multivalent terminal sugar chain determinants.

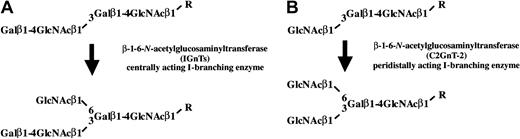

Structures of the I and i antigens and their biosynthetic pathways.

The structure of the i antigen determinant is a linearN-acetyllactosamine unit repeated, and that of the I antigen determinant is a branched poly-N-acetyllactosamine. Conversion of the i structure to the branched I structure is catalyzed by I-branching β1-6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (IGnT). Centrally acting IGnT is illustrated in panel A, whereas peridistally acting IGnT (C2GnT-2) presented in panel B catalyzes the I-branching reaction using an acceptor substrate with the terminal structure GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-R instead of Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-R.

Structures of the I and i antigens and their biosynthetic pathways.

The structure of the i antigen determinant is a linearN-acetyllactosamine unit repeated, and that of the I antigen determinant is a branched poly-N-acetyllactosamine. Conversion of the i structure to the branched I structure is catalyzed by I-branching β1-6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (IGnT). Centrally acting IGnT is illustrated in panel A, whereas peridistally acting IGnT (C2GnT-2) presented in panel B catalyzes the I-branching reaction using an acceptor substrate with the terminal structure GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-R instead of Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-R.

To understand how I-branched poly-N-acetyllactosamines are synthesized, it has been of interest to investigate the I-branching enzyme, β-1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (IGnT1). The cDNA encoding IGnT was first cloned from human embryonal carcinoma cells, PA-1, by the transient expression method,11 and was named IGnT. Another I-branching enzyme was identified and designatedC2GnT-M or C2/4GnT (later renamedC2GnT-2).12,13 It was reported that IGnT has the strong I-branching activity, whereas C2GnT-2 exhibits only weak peridistal I-branching activity.12IGnT is located on chromosome 6p24 and encodes centrally acting IGnT activity that produces a Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3(GlcNAcβ1-6)Galβ1-4GlcNAc structure. On the other hand, C2GnT-2 is located at 15q21-22 and encodes peridistally acting IGnT activity that forms a GlcNAcβ1-3(GlcNAcβ1-6)Galβ1-4GlcNAc structure.

In persons with the adult i phenotype, RBCs express i antigen but little I antigen. The frequency of the adult i phenotype, inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, was first reported to be 5 of 22 000.1 In the i phenotype, it is thought that the lack of I antigen is the result of IGnT enzyme inactivation. Recently, individuals showing the i phenotype for blood group have been reported to have missense mutations in the conventional IGnTgene.14 These mutations were responsible for abolishment of the conventional IGnT activity and resulted in a null phenotype of erythrocyte I antigen, although I antigen expression was not examined in the other tissues. In previous studies, healthy quantities of I antigen have been detected in saliva, milk, and plasma of an individual with the adult i phenotype of erythrocytes.15 16 These findings suggest that there may be additional IGnT genes responsible for histo-blood group I antigen, and the elucidation of the genes should contribute to a better understanding of the blood groupI gene locus.

In this study, we report a novel IGnT gene, designatedIGnT3, and compare its expression with that of the conventional IGnT (IGnT1) and another novel isoform, IGnT2. All 3 isoforms consist of 3 exons and share the second and third exons. IGnT3 transcript expression is demonstrated in bone marrow and is induced markedly during erythroid cell differentiation. Only IGnT3 is detected in reticulocytes. In addition, we describe molecular genetic data onIGnTs of an adult i pedigree, in which missense mutations are found in the common exons 2 and 3. It is demonstrated that the novel IGnT3 may be the most feasible candidate for the blood group I gene and that the mutations found in exons 2 and 3 abolish all 3 I-branching enzymic activity and cause the adult i phenotype in erythrocytes.

Materials and methods

Cloning of novel human IGnT cDNAs

We found 2 IGnT-homologous regions in the genomic sequence database using BLAST. Both existed on chromosome 6 (accession no. NT_007291) near the conventional IGnT gene. One was located as the first exon upstream of the IGnT-first exon, and the other was located as the first exon downstream of theIGnT-first exon. It was expected that these 2 genes andIGnT share second and third exons. Therefore, the conventional IGnT was named IGnT1, and these novel genes were designated IGnT2 and IGnT3. On the basis of the above information, we designed primers for theseIGnTs: forward primer for IGnT1, 5′-tgaggcatgcctttatcaatgcgttacc-3′; forward primer forIGnT2, 5′-tgaatgatgggctcttggaagcactgtc-3′; forward primer for IGnT3, 5′-gtgaaaataatgaacttttggaggtactgctt-3′; reverse primer for the 3 genes, 5′-tgaatagctcaaaaatacctgctgggttgt-3′. PA-1 cell cDNA was used as a template. These 3 genes were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and then PCR products were sequenced using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Kit with an ABI3100 sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). These amplified fragments were also subcloned into the pCRII vector.

Preparation of RNA from lineage-specific differentiated hematopoietic cells and reticulocyte-enriched fraction

Lineage-specific differentiation of hematopoietic cells was conducted from adult bone marrow CD34+ cells, and cDNA from the cells was prepared according to the previous reports17 18—that is, purified CD34+ cells were differentiated into the myeloid, erythroid, or megakaryocytic lineage using an optimal combination of hematopoietic growth factors for each lineage in serum-free liquid medium. Cells were cultured for 6 days in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 1% bovine serum albumin, 10 μg/mL bovine pancreatic insulin, 200 μg/mL human transferrin (BIT 9500; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), 40 μg/mL human low-density lipoproteins (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA), and 10−4 M 2-mercaptoethanol. The following factors were added: stem cell factor (SCF; 50 ng/mL, Sigma) and granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; 10 ng/mL, Genetics Institute) for myeloid differentiation; SCF (50 ng/mL) and erythropoietin (EPO, 3 U/mL; Chemicon International) for erythroid differentiation; and SCF (50 ng/mL), thrombopoietin (TPO; 20 ng/mL), and l-asparagine (2 mg/mL) for megakaryocytic differentiation. The purity and maturation stages of the differentiated cells were examined using Wright-Giemsa staining and flow cytometric surface marker analysis. Approximately 70% cells were differentiated into myeloid lineage by GM-CSF treatment, judging from the morphology and cell surface CD11b (C3bi receptor α) expression. Expression of CD61 (glycoprotein IIIa) and glycophorin A, however, stayed in the small percentage before and after 6-day culture with GM-CSF. On the other hand, CD61 was expressed on 60% of TPO-treated cells, and 70% of the cells exhibited megakaryocytic morphology. However, expression of CD11b and CD61 was less than 3% and 15%, respectively, after TPO treatment. For EPO-induced differentiation, more than 90% of the cells were judged as differentiated erythroid cells by cytologic examination, and approximately 70% of the cells displayed positivity for glycophorin A. CD11b and glycophorin A expression were less than 10% after EPO treatment. Cell surface marker expression clearly indicated the commitment of the treated cells into each cell lineage. Monoclonal antibodies against CD11b, CD61, and glycophorin A were purchased from DAKO Japan (Tokyo).

The reticulocyte-enriched fraction was prepared from human peripheral blood using Optiprep (Nycomed Amersham, Oslo, Norway) according to the manual supplied. Optiprep was provided as a solution of 60% (wt/vol) iodixanol in water and had a density of 1.32 g/mL. OptiPrep stock was made at first from 10 mL OptiPrep and 0.1 mL of 1 M HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N'-2-ethanesulfonic acid)–NaOH (pH 7.4), and the density solutions were prepared by diluting the OptiPrep stock with HEPES-buffered saline. The Optiprep stock was added to whole blood to adjust its density to 1.105 g/mL, and a discontinuous gradient was made with the 4 density solutions (1.100, 1.095, 1.092, 1.077 g/mL) and sample (1.105 g/mL). After centrifugation at 800g for 30 minutes, the gradient was divided into 7 equivolume fractions. The recovered top layer of the gradient consisted of erythrocytes and enriched reticulocytes. Reticulocyte was identified with supravital staining using new methylene blue,19 and the reticulocytes were counted under a microscope. The percentage in the top layer was concentrated up to 12.1% compared with whole blood (1.0%), and no other cell types, including mononuclear cells and granulocytes, were detected. Total RNA of reticulocytes was extracted with Isogen (Nippon Gene) and was used for cDNA synthesis.

Quantitative analysis of IGnT transcripts in human tissues and hematopoietic cells by real-time PCR

The amount of IGnT transcripts in the various tissues and hematopoietic cells was determined by the real-time PCR method, as described in detail.20 21 Marathon Ready cDNAs of various human tissues were purchased from Clontech. The standard curves for theIGnT cDNAs and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA, as an endogenous control, were generated by serial dilution of a pDONR 201 vector DNA containing theIGnT gene encoding the putative catalytic domain and a pCR2.1 (Invitrogen) DNA containing the GAPDH gene. Primer sets and probes for IGnTs were as follows: forward primer for IGnT1, 5′-acaaactaatgatccatgagaagtcttc-3′; reverse primer for IGnT1, 5′-ccattatatatgccaagggaaagtc-3′; probe for IGnT1, 5′-FAM-tgcaaggaatacttgacccagagccact-MGB-3′; forward primer for IGnT2, 5′-gctatgagtacatggttcgaagcc-3′; reverse primer for IGnT2, 5′-gccgaagtctttgtggatggt-3′; probe for IGnT2, 5′-FAM-tgaagaagaggctgggttccctttagcttaca-MGB-3′; forward primer for IGnT3, 5′-aatgccagtctttttgtggga-3′; reverse primer for IGnT3, 5′-atgtagtgattctgggtcaggtaatc-3′; and probe for IGnT3, 5′-FAM-aatatattaccatcacctttgcgaagtgtcccttg-MGB-3′. ForGAPDH, we used Pre-Developed TaqMan Assay Reagents and Endogenous Human GAPDH (Applied Biosystems). Primers, probes, and cDNAs were added to the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) that contained all reagents for PCR. The PCR conditions included 1 cycle at 50°C for 2 minutes, 1 cycle at 95°C for 10 minutes, and 50 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. PCR products were continuously measured with an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The relative amount ofIGnT transcript was normalized to the amount of mRNA, total RNA, or GAPDH transcript in the same cDNA. When usingGAPDH as the endogenous control, absolute transcript expression values lower than 10 amol were thought to be under the detectable level, and the data were eliminated before the normalization.

Volunteer samples

An adult i pedigree, 3 members with the adult i phenotype and 1 member with the common I phenotype, and 4 common I volunteers served as the study subjects. All 3 adult i individuals have congenital cataracts. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with Helsinki protocol. Total RNA and Genomic DNA were prepared from their peripheral blood cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit and the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA sequencing was performed using PCR amplicons of each first exon and the common second and third exons for IGnT1, IGnT2, andIGnT3, respectively. PCR amplifications of the first exons were achieved by using the primer pairs of 5′-taaggtctcatataactcagtggatg-3′ and 5′-gggtgagaactatatatgttccagtt-3′ for IGnT1, 5′-tgtagacacaggttgcagcttagca-3′ and 5′-cttttgtcctgtgaacagagcggtt-3′ for IGnT2, or 5′-ctgggcttagctgagcctttgcaa-3′ and 5′-ctgggcttagctgagcctttgcaa-3′ forIGnT3. Common second and third exons were amplified using the primer pairs 5′-ctgaagtggagaaaccctggctta-3′ and 5′-aaccctggattccacagctacctt-3′, and 5′-agttgtagttagtcggagagtacct-3′ and 5′-tataattacgtagccaggtcctgaa-3′, respectively. Moreover, we examined the cDNA sequence of the IGnT3 transcript that was amplified from the RNA samples using the primers 5′-gctttcactctgctcagcgtggtcat-3′ and 5′-tacccagccatcctgttagtgtatt-3′. Then amplified fragments ofIGnT3 were subcloned into the pCRII-TOPO vector using a TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen). These purified PCR products, obtained using the MinElute PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen), and cloned purified plasmids, obtained using the QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen), were sequenced using the DYEnamic ET terminator cycle sequencing kit with MegaBACE 500 (Amersham Biosciences).

Expression of IGnTs in Chinese hamster ovary cells

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were cultured in α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and used for overexpression experiments on IGnTs. A full open-reading frame was cloned into the pcDNA3.1/Hygromycin(+) vector from the subcloned pCRII-IGnTs, resulting in pcDNA3.1-IGnTs. cDNA from mutated allelesI3i1 with A nucleotide at position 1049 andI3i3 with A nucleotide at position 1006 were ligated to pcDNA3.1/Hygromycin(+) vector. The plasmids were stably transfected into CHO cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and then the transfectants were selected using 0.6 mg/mL hygromycin. Alterations of cell surface I/i antigen expression were examined with human monoclonal antibodies OSK-2822 for i-antigen and OSK-1423 for I-antigen using FACScalibur (Becton Dickinson). OSK-28 and OSK-14 were originally designated 2A-70 and anti-I No. 068, respectively, and were generous gifts from Dr J. Takahashi, Red Cross Blood Center (Osaka, Japan).

Results

Identification of IGnT2 and IGnT3

We found 2 IGnT-homologous regions in the human genomic sequence database using tBLASTn in NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) BLAST. One existed on BAC clone RP11-360O19 (chromosome 6 complete sequence; accession no. AL139039), and the other existed on BAC clone RP11-421M1 (chromosome 6 complete sequence; accession no.AL358777) as shown in Figure 2A. The former homologous region was located upstream of the conventionalIGnT-exon 1 (IGnT1 exon 1) on RP11-360O19, and the latter homologous region was located upstream of the conventionalIGnT-exon 2 and 3 (IGnT1 exons 2 and 3) on RP11-421M1. These sequences of AL139039 and AL358777 were included in an NT-numbered sequence, NT_007291 (Figure 2B). We speculated that the homologous regions are the first exons of novel IGnTs and are designated IGnT2 and IGnT3, as documented in “Materials and methods.” We also speculated that the transcripts for IGnT1 (conventional IGnT), IGnT2, and IGnT3 are derived by alternative splicing, sharing exons 2 and 3. Using primer pairs, as indicated by arrowheads in Figure 2A, which were designed from information on the BAC clone sequence data (RP11-360O19 and RP11-421M1), we could successfully amplify cDNA clones of IGnT2 and IGnT3 in addition toIGnT1. Comparison of the cDNA sequences with NT_007291 revealed that our 3 IGnT cDNA sequences—IGnT1, IGnT2, and IGnT3—are completely identical to the genomic data (Figure 2C). Thus, the connection between the 2 BAC clones, RP11-360O19 and RP11-421M1, could be thought as valid. Sequence analyses revealed that IGnT2 and IGnT3 consisted of 3 exons like IGnT1, and 3 isoforms shared exon 2, which encodes 31 amino acids, and exon 3, which encodes 62 amino acids (Figure 2C). Each exon 1 of the 3 IGnTs was tandemly arranged in the order of IGnT2, IGnT1, andIGnT3 upstream of exon 2. These 3 IGnTs are derived from alternative splicing of a single gene, such as mouseIGnT A and IGnT B.24 The predicted amino acid sequence from IGnT1 exon 1 showed 65% and 66% homology to those of IGnT2 and IGnT3, respectively. Homology in amino acid sequence corresponding to exon 1 between IGnT2 and IGnT3 was 65%. A Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy analysis25 revealed that 3 IGnTs showed the type 2 transmembrane topology typical of most glycosyltransferases. Nine cysteine residues were conserved among 3 IGnTs. IGnT2 was identified as the orthologue of mouse IGnT B,24 but IGnT3 was a novel enzyme that has not been reported in any species.

Genomic organization and multiple amino acid alignments of IGnT and novel IGnT-homologous sequences.

(A) Two BAC clones containing novel IGnT-homologous sequences. 2 BAC clones, RP11-360O19 and RP11-421M1, are illustrated. Boxes represent exons. RP11-360O19 contains IGnT1-exon 1 and a sequence homologous to IGnT1-exon 1 (IGnT2-exon 1), and RP11-421M1 contains exons 2 and 3 of IGnT1 and another sequence homologous to IGnT1-exon 1 (IGnT3). Arrowheads above the exons indicate the positions of PCR primers designed in the present study. (B) Genomic structure of the human IGnT1, IGnT2, and IGnT3. These 3 genes are arranged as 3 exons contained within the sequence of NT_007291 from the chromosome 6 working-draft sequence segment. Nucleotides from 219 000 to 319 000 of NT_007291 are illustrated in this figure. NT numbers are assigned to and are guaranteed as the high-quality genome sequences by NCBI. A scale bar of 2 kb is presented at the right bottom corner. (C) Multiple amino acid sequence analysis of human IGnT1, IGnT2, and IGnT3. Identical residues are indicated by boxes. Putative transmembrane domains are underlined. The positions of conserved cysteines are indicated by asterisks, and the splicing sites are indicated by arrows.

Genomic organization and multiple amino acid alignments of IGnT and novel IGnT-homologous sequences.

(A) Two BAC clones containing novel IGnT-homologous sequences. 2 BAC clones, RP11-360O19 and RP11-421M1, are illustrated. Boxes represent exons. RP11-360O19 contains IGnT1-exon 1 and a sequence homologous to IGnT1-exon 1 (IGnT2-exon 1), and RP11-421M1 contains exons 2 and 3 of IGnT1 and another sequence homologous to IGnT1-exon 1 (IGnT3). Arrowheads above the exons indicate the positions of PCR primers designed in the present study. (B) Genomic structure of the human IGnT1, IGnT2, and IGnT3. These 3 genes are arranged as 3 exons contained within the sequence of NT_007291 from the chromosome 6 working-draft sequence segment. Nucleotides from 219 000 to 319 000 of NT_007291 are illustrated in this figure. NT numbers are assigned to and are guaranteed as the high-quality genome sequences by NCBI. A scale bar of 2 kb is presented at the right bottom corner. (C) Multiple amino acid sequence analysis of human IGnT1, IGnT2, and IGnT3. Identical residues are indicated by boxes. Putative transmembrane domains are underlined. The positions of conserved cysteines are indicated by asterisks, and the splicing sites are indicated by arrows.

Expression of IGnTs in CHO cells

It was reported that CHO cells do not express I-antigen or IGnT activity but do express i-antigen.11 26 After the establishment of IGnT-transfected CHO cells, we analyzed the cell surface expression of I- and i-antigens. Flow cytometric examination revealed an up-regulation of I-antigen and a concomitant down-regulation of i-antigen in IGnT2- andIGnT3-transfected CHO cells and inIGnT1-transfected cells (data not shown).

Distribution of IGnT transcripts in various human tissues and cells

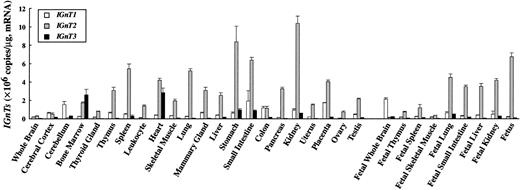

Expression levels of IGnT transcripts in various human tissues were determined by real-time PCR and are summarized in Figure3. IGnT2 transcript was expressed in many adult and fetal tissues ubiquitously and more abundantly than the transcript for IGnT1 orIGnT3. The expression of IGnT2 was strongest in the stomach and kidney, followed by fetus, small intestine, spleen, lung, placenta, heart, fetal lung, and fetal liver. Whole brain, cerebral cortex, fetal brain, cerebellum, and skeletal muscle expressed the IGnT2 transcript at a very low level. The expression pattern of IGnT1 was similar to that of IGnT2. However, the IGnT1 transcript was more abundant in cerebellum and fetal brain than the IGnT2 transcript. In contrast, the expression pattern of IGnT3 transcript was different from that of the IGnT1 or IGnT2transcript. IGnT3 was strongly expressed in bone marrow, heart, stomach, and small intestine, and at insignificantly low or undetectable levels in the other adult tissues and fetal tissues examined. It was noteworthy that IGnT3 was most abundantly expressed in bone marrow. In peripheral leukocytes, in contrast,IGnT2 was highly expressed but IGnT3 was undetectable.

Quantitative analysis of IGnT transcripts in human tissues by real-time PCR.

Standard curve for IGnTs was generated by serial dilution of each plasmid DNA. The expression level of IGnT transcripts was normalized to micrograms of mRNA. Data were obtained from triplicate experiments and are indicated as mean ± SD.

Quantitative analysis of IGnT transcripts in human tissues by real-time PCR.

Standard curve for IGnTs was generated by serial dilution of each plasmid DNA. The expression level of IGnT transcripts was normalized to micrograms of mRNA. Data were obtained from triplicate experiments and are indicated as mean ± SD.

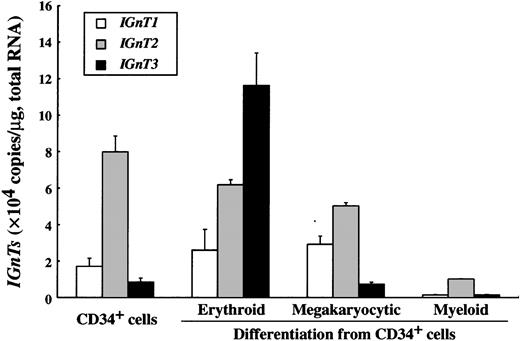

Expression of IGnT transcripts in lineage-specific differentiated hematopoietic cells and reticulocytes

Given that erythroblasts are the major constituent in bone marrow, we examined the change in the expression level of the 3IGnTs during hematopoietic cell differentiation (Figure4). CD34+ progenitor cells expressed the IGnT2 transcript most abundantly, and the expression levels of IGnT1 and IGnT3 were relatively low. It was of interest that the IGnT3 transcript increased dramatically during erythroid differentiation, whereas the expression of IGnT2 was slightly down-regulated. On the other hand, during megakaryocytic differentiation, IGnT3expression did not change at all. IGnT1 was up-regulated, and IGnT2 was down-regulated to some extent. In contrast, the transcription of all IGnTs was down-regulated during myeloid differentiation.

Changes of IGnT transcript expression during hematopoietic cell differentiation from CD34-positive cells.

The expression level of IGnTs was analyzed by real-time PCR. Standard curve for IGnTs was generated by serial dilution of each plasmid DNA. The expression level of IGnT transcripts was normalized to micrograms of total RNA. Data were obtained from triplicate experiments and are indicated as mean ± SD.

Changes of IGnT transcript expression during hematopoietic cell differentiation from CD34-positive cells.

The expression level of IGnTs was analyzed by real-time PCR. Standard curve for IGnTs was generated by serial dilution of each plasmid DNA. The expression level of IGnT transcripts was normalized to micrograms of total RNA. Data were obtained from triplicate experiments and are indicated as mean ± SD.

Up-regulation of IGnT3 transcript expression during erythroid differentiation suggested that the biosynthesis of blood group I determinants in terminally differentiated erythrocytes resulted from the IGnT3 remaining in human erythroid-committed cells and reticulocytes. To test this possibility, the level ofIGnT transcript was quantitated by real-time PCR using the reticulocyte-enriched fraction. As shown in Table1, the IGnT3 transcript clearly remained in reticulocytes, but we could not detect transcripts of IGnT2 and IGnT1.

Quantitative analysis of IGnT1, IGnT2, andIGnT3 transcripts in human reticulocyte

| Gene name . | Expression level perGAPDH . |

|---|---|

| IGnT1 | ND |

| IGnT2 | ND |

| IGnT3 | 0.25 ± 0.08 |

| Gene name . | Expression level perGAPDH . |

|---|---|

| IGnT1 | ND |

| IGnT2 | ND |

| IGnT3 | 0.25 ± 0.08 |

Expression of IGnT transcripts in human reticulocyte-enriched fraction was analyzed by real-time PCR. Standard curves for IGnTs and GAPDH were generated by serial dilution of each plasmid DNA. The expression level ofIGnT transcript was normalized to that of GAPDHtranscript, measured in the same cDNAs. Data were obtained from triplicate experiments and are expressed as mean ± SD.

ND indicates not detected.

Missense mutations identified in IGnT genes of adult i phenotype

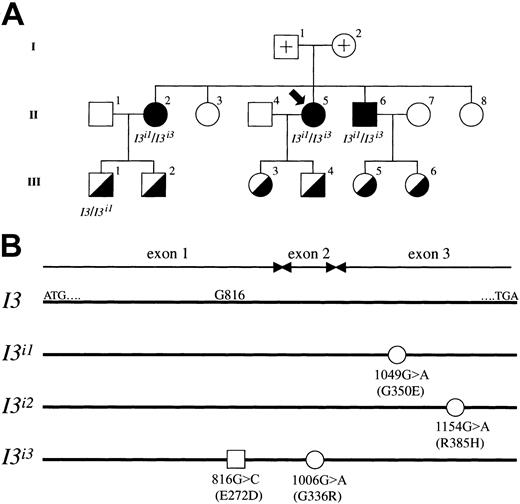

Molecular genetic investigations were carried out using samples from an adult i pedigree, and the results are summarized in Figure5. First, we determined the genomic sequence of the coding regions for IGnT1, IGnT2, andIGnT3 genes using samples from adult i and common I phenotypes. In the first exons of IGnT1 andIGnT2, no mutation or polymorphism was found. Moreover, in the first exon of IGnT3, the nucleotide substitution 816G>C was observed in members of the adult i pedigree. This substitution, however, which predicts the amino acid alteration of Glu272Asp, was detected not only in the adult i phenotype but also in 2 of 4 persons with the common I phenotype who are investigators in our laboratory and volunteered for the examination of IGnT genotype. Each was heterozygous for the 816G>C substitution. The high frequency of the allele, having only the 816G>C substitution, in the population indicates that it is a nonfunctional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP). On the other hand, nucleotide substitutions of 1006G>A and 1049G>A were observed in the common second and third exons, respectively, of IGnT genes from the adult i phenotype. Neither was found in persons with the common I phenotype. Furthermore, we examined the cDNA sequence of the IGnT3 transcript that was subcloned into pCRII-TOPO. In the adult i pedigree, individuals 2, 5, and 6 of generation II with the adult i phenotype were found to be heterozygous withI3i1/I3i3 alleles, and a member with the common I phenotype, individual 1 in generation III, was found to be heterozygous withI3/I3i1. Nucleotide substitutions 1049G>A and 1006G>A in allelesI3i1/I3i3 predict amino acid changes of Gly350Glu and Gly336Arg, respectively. We found that the 816G>C SNP and the 1006G>A mutation coexist in the sameI3i3 allele. In addition, theI3i3 allele containing the 1006G>A mutation was newly found in this study.

Segregation of wild-type I3,I3i1, and I3i3 alleles in an adult i pedigree.

(A) Pedigree drawings I, II, and III represent the first, second, and third generation, respectively, and the propositus is indicated by an arrow. Filled and half-filled symbols for male (square) and female (circle) denote a person with adult i and common I phenotypes, respectively. Open symbols with a cross represent the parents of the propositus; the samples could not be obtained because they had already died. The other open symbols denote persons with common I phenotype, but genotyping was not conducted. The genotype of the half-filled symbols is a heterozygote of wild-type I3 and mutated alleles, though genotypic analysis of individuals 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in III was not conducted. All adult i phenotypes were derived from heterozygotes of mutated I3i1 andI3i3 alleles. (B) Schematic diagrams of mutated alleles found in the adult i pedigree. I3 indicates the coding region of the wild-type IGnT3 presented in this study. ATG and TGA denote the enzyme's translation initiation and termination codons, respectively. Open circles represent nucleotide substitutions 1049G>A in the I3i1 allele, 1154G>A in the I3i2 allele, and 1006G>A in theI3i3 allele, respectively. The alleleI3i3 was found in the present study, whereas alleles I3i1 and I3i2have already been reported by Yu et al.14 These mutations in I3i1, I3i2, andI3i3 predict amino acid alterations of Gly350Glu, Arg385His, and Gly336Arg, respectively. Note that positions 1154 and 385 in allele I3i2 are based on theIGnT3 gene nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences, respectively. The open square represents a possible nonfunctional missense mutation in the allele I3i3 exon 1 ofIGnT3.

Segregation of wild-type I3,I3i1, and I3i3 alleles in an adult i pedigree.

(A) Pedigree drawings I, II, and III represent the first, second, and third generation, respectively, and the propositus is indicated by an arrow. Filled and half-filled symbols for male (square) and female (circle) denote a person with adult i and common I phenotypes, respectively. Open symbols with a cross represent the parents of the propositus; the samples could not be obtained because they had already died. The other open symbols denote persons with common I phenotype, but genotyping was not conducted. The genotype of the half-filled symbols is a heterozygote of wild-type I3 and mutated alleles, though genotypic analysis of individuals 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in III was not conducted. All adult i phenotypes were derived from heterozygotes of mutated I3i1 andI3i3 alleles. (B) Schematic diagrams of mutated alleles found in the adult i pedigree. I3 indicates the coding region of the wild-type IGnT3 presented in this study. ATG and TGA denote the enzyme's translation initiation and termination codons, respectively. Open circles represent nucleotide substitutions 1049G>A in the I3i1 allele, 1154G>A in the I3i2 allele, and 1006G>A in theI3i3 allele, respectively. The alleleI3i3 was found in the present study, whereas alleles I3i1 and I3i2have already been reported by Yu et al.14 These mutations in I3i1, I3i2, andI3i3 predict amino acid alterations of Gly350Glu, Arg385His, and Gly336Arg, respectively. Note that positions 1154 and 385 in allele I3i2 are based on theIGnT3 gene nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences, respectively. The open square represents a possible nonfunctional missense mutation in the allele I3i3 exon 1 ofIGnT3.

IGnT3 with 1049G>A and 1006G>A mutations fails to express I-antigen in CHO cells

As described in the previous section, the 816G>C substitution coexisted with the 1006G>A mutation in the I3i3allele. The frequency of the allele with the 816G>C mutation alone was high in the population. To exclude the possibility thatIGnT3 cDNA containing the 816G>C mutation alone is associated with the adult i phenotype, we have established CHO cells transfected with IGnT3 cDNA containing the 816G>C SNP alone (pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [816G>C]) or the wild-typeIGnT3 (pcDNA3.1-IGnT3). Those cells were examined for I/i antigen expression by flow cytometry. Cells transfected withIGnT3 (816G>C) showed the same I/i expression profile as the wild type (data not shown), indicating that the 816G>C substitution is not the I-inactivating mutation. In addition, we have established CHO cells transfected with IGnT3 cDNA containing the 1049G>A mutation alone (pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [1049G>A]) orIGnT3 cDNA having both mutations of 816G>C and 1006G>A (pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [816G>C/1006G>A]). On flow cytometric analysis, cells transfected with the wild-type IGnT3exhibited a remarkable increase of I-antigen expression and suppression of i-antigen (Figure 6L,K, respectively). Such an alteration of I/i expression was not observed in the CHO cells transfected with IGnT3 (1049G>A) and IGnT3(816G>C/1006G>A) (Figure 6E-F,H-I, respectively). Furthermore, we have analyzed CHO cells transfected with IGnT3 cDNA having the 1006G>A mutation alone (pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [1006G>A]). Cells exhibited the same I/i expression pattern as CHO cells transfected with IGnT3 (816G>C/1006G>A) andIGnT3 (1049G>A) (data not shown). Thus, 1049G>A inI3i1, 1154G>A in I3i2,and 1006G>A in I3i3 were determined to be responsible for the inactivation of IGnT3, whereas 816G>C in I3i3 was not responsible for it. The expression of the wild-type and mutant IGnT3 transcripts in the transfected CHO cells was examined and confirmed by real-time PCR (data not shown).

Flow cytometric analyses of CHO cells transfected withIGnT3 cDNAs containing the 1049G>A mutation or the 1006G>A mutation.

CHO cells transfected with the vector alone (A-C), pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [1049G>A] (D-F), pcDNA3.1-IGnT3[816G>C/1006G>A] (G-I), and wild-type pcDNA3.1-IGnT3(J-L) were analyzed for I/i antigen expression by flow cytometry. Control immunoglobulin M (IgM) (A, D, G, J), anti-i antibody OSK-28 (B, E, H, K), and anti-I antibody OSK-14 (C, F, I, L) were used for the staining.

Flow cytometric analyses of CHO cells transfected withIGnT3 cDNAs containing the 1049G>A mutation or the 1006G>A mutation.

CHO cells transfected with the vector alone (A-C), pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [1049G>A] (D-F), pcDNA3.1-IGnT3[816G>C/1006G>A] (G-I), and wild-type pcDNA3.1-IGnT3(J-L) were analyzed for I/i antigen expression by flow cytometry. Control immunoglobulin M (IgM) (A, D, G, J), anti-i antibody OSK-28 (B, E, H, K), and anti-I antibody OSK-14 (C, F, I, L) were used for the staining.

Discussion

The blood group I antigen determinant is synthesized by the IGnT enzyme after the sequential action of β1-3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (β3Gn-T) and β1-4-galactosyltransferase (β4GalT). Such β3Gn-Ts andβ4GalTs are composed of the respective gene family members.27-30 From this point of view, it has been thought that the conventional IGnT also forms a gene family such asβ3Gn-Ts and β4GalTs. As expected, we cloned and characterized the novel human IGnT2 and IGnT3 in this report.

Missense mutations in IGnT were reported to be responsible for inactivation of the IGnT enzyme and result in a null phenotype of erythrocyte I antigen.14 However, the mutations were examined only in the IGnT1 gene in their study. On the other hand, healthy quantities of I antigen have been detected in saliva, milk, and plasma of persons with the adult i phenotype of erythrocytes.15 16 The discrepancy between blood type i and histo-blood group I antigens might have resulted from novelIGnTs, which have not cloned yet, showing a different profile of tissue distribution from conventional IGnT1.According to our own experiments of the transcript expression and the previous experimental data on the BAC clones, it is considered that 3IGnTs are generated by alternative splicing of a single gene, sharing exons 2 and 3, which was mapped at major blood group I locus on chromosome 6. The first exon of each gene might have been generated by gene duplication. All 3 isoforms of IGnT exhibited centrally acting IGnT activities, and their substrate specificity will be described elsewhere (A.T., unpublished data, 2002).

In terms of tissue distribution, IGnT1 and IGnT2showed similar profiles, with the transcript expression ofIGnT2 greater than that of IGnT1. Brain, especially cerebellum and fetal whole brain, was the only tissue in which the expression level of IGnT1 was higher than that ofIGnT2. IGnT1 may play a major role in synthesizing I antigens in the brain and may contribute to the development and function of the brain. IGnT2 transcripts, already expressed in fetal tissues, may consequently contribute to tissue development.IGnT3 transcripts were not detected in fetal liver, which is a major tissue for fetal hematopoiesis. This is consistent with the i phenotype of fetal erythrocytes. The above data should be considered carefully to analyze IGnT expression in each tissue because the cell type was not identified clearly. MouseIGnT A (mIGnT A) and IGnT B(mIGnT B) have been reported.24mIGnT A and mIGnT B were orthologous to humanIGnT1 and IGnT2, respectively, and their tissue distribution was almost the same in various tissues in mouse. However, the mIGnT A gene is regulated by a promoter that is different from that for the mIGnT B gene, though the regulatory mechanisms of these genes have not been clarified.31

It is of interest that the tissue distribution of IGnT3 is different from that of the others. IGnT3 transcript expression was noted in the stomach, small intestine, bone marrow, and heart, but the expression level was low in the other tissues. The transcript level of IGnT2 was the highest among the 3 in leukocytes, spleen, and myeloblastoid cells derived from CD34+ cells. IGnT1 and IGnT3transcripts were not detected or the expression level was very low in such tissues or cell lineages. This suggests that I antigen in leukocytes is mainly determined by IGnT2. On the other hand, IGnT1 and IGnT2 probably determine I antigen expression in megakaryocytes. By contrast, we found that the IGnT3transcript level was the highest among the 3 in bone marrow cells, erythroblasts derived from CD34+ cells, and reticulocytes. These observations suggest a characteristic involvement of IGnT3 in I-antigen expression in erythrocytes. Moreover, it is suggested that the discrepancy between blood group and histo-blood group I/i antigen expression can be explained by differential gene regulation ofIGnT3 and the other IGnTs andC2GnT-2.11,12,15,16 Although such gene regulation mechanism has not been examined in humans, it is noteworthy that remarkable IGnT3 gene expression is induced during erythroid differentiation of CD34+ cells. The regulatory region of human IGnT3 may be different from those ofIGnT1 and IGnT2 and would be in the downstream of erythropoietin signal transduction.32

We have conducted molecular genetic studies of an adult i pedigree and have revealed that the adult i phenotype resulted from heterozygous mutations in exon 2 (1006G>A) and exon 3 (1049G>A) in theIGnT3 gene. The results predict the changes Gly336Arg and Gly350Glu, respectively, in IGnT3, and the mutated cDNAs failed to express I antigen on the CHO cell surface. Although the 1049G>A and 1154G>A mutations in exon 3 have been examined by Yu et al,14 another missense mutation 1006G>A is a novel one presented in the current study. The genomic organization ofIGnT gene family members reported here provides us with better understanding of the adult i phenotype—that is, the missense mutations in exon 2 or 3 simultaneously abolish the activity of all 3 enzymes, IGnT1, IGnT2, and IGnT3.

From the expression profile analysis, we conclude that the most feasible candidate for the blood group I gene is notIGnT1/2 but IGnT3. It is strongly suggested that the I-antigen phenotype in erythrocytes is determined byIGnT3, whereas I-antigen expression in other tissue fluids, including saliva, milk, and plasma, is regulated by the otherIGnTs and C2GnT-2. Actually, the transcript level of IGnT2 was the highest among the 3 in the mammary gland. IGnT2 may play a major role in synthesizing soluble I-antigens in milk. It is of interest that the water-soluble I blood group substance was detected in white i adults.15,16 In addition, it was reported that the adult i phenotype in Japanese persons is often associated with congenital cataracts.33 The i blood type of individuals in the present study is associated with cataracts, as described in “Materials and methods.” However, it has been reported that the i blood type of white persons has a reduced association with congenital cataracts.34 Given that the frequency of the i phenotype is rare and that mutations in the IGnT gene locus may occur in a sporadic manner, there may be at least 2 different types of adult i mutation. One occurs in Asians, and the other occurs in white persons. Hence, further molecular genetic studies of the adult i phenotype may reveal that mutations develop in exon 1 ofIGnT3, which inactivates only IGnT3, in non-Asian populations. In such persons, IGnT1, IGnT2, and their gene products should be intact, especially in milk, saliva, plasma, and corneal epithelium in which they are expressed. Investigations to examine whether the above hypothesis is true are highly awaited.

We thank Dr Junko Takahashi and Dr Hajime Yamano of the Red Cross Blood Center in Osaka, Japan, for providing anti-i OSK-28 and anti-I OSK-14 monoclonal antibodies. We thank Kumi Ishikawa, Shigemi Sugioka, Kahori Tachibana, and Risa Kawamoto for their technical assistance.

Nucleotide sequences of human IGnT2 and IGnT3reported in this paper have been placed in the DDBJ/GenBank/EBI Data Bank with accession numbers AB078432 and AB078433, respectively.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 5, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2838.

Supported in part by the R&D Project of Industrial Science and Technology Frontier Program (R&D for Establishment and Utilization of a Technical Infrastructure for Japanese Industry) of New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

Hisashi Narimatsu, Glycogene Function Team, Research Center for Glycoscience, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, Central-2 OSL, 1-1-1 Umezono, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-8568, Japan; e-mail:h.narimatsu@aist.go.jp.

![Fig. 6. Flow cytometric analyses of CHO cells transfected withIGnT3 cDNAs containing the 1049G>A mutation or the 1006G>A mutation. / CHO cells transfected with the vector alone (A-C), pcDNA3.1-IGnT3 [1049G>A] (D-F), pcDNA3.1-IGnT3[816G>C/1006G>A] (G-I), and wild-type pcDNA3.1-IGnT3(J-L) were analyzed for I/i antigen expression by flow cytometry. Control immunoglobulin M (IgM) (A, D, G, J), anti-i antibody OSK-28 (B, E, H, K), and anti-I antibody OSK-14 (C, F, I, L) were used for the staining.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/101/7/10.1182_blood-2002-09-2838/3/m_h80734053006.jpeg?Expires=1769234269&Signature=SnVjddXuDmNNSgJHhywdbM5DayM2ojQAlwCECV~yx4Z-4dmOtquAqiJO-ogHtPPhLIBUOeSCL2WFgR41nJgYYiFVRwYiHIRWKX4zw1wylPbsxUjDvr1ctP3uvpUAe1GqJCU~-GINAUinGdEmMCLJxhD2WsVJdMliS1K1DRcN-jD99X3vVMKdYEYrXZPj0kXZG1wqNjk~711btYcaIpUNvaPDOzpzK7h-zf2Z9OaHRGplv7a~5q~m87hJwo8EhtzzT9t8Uh3Uem8uW99~3-J6s3KDw02jBvZ1SXwpiKs7-hvK2fi91uloBWl-nZjVBeCSq5Qd2888SIaQjA~h7QHaGA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal