Abstract

Although accumulating evidence strongly suggests that aplastic anemia (AA) is a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease, no target antigens have yet been described for AA. In autoimmune diseases, target autoantigens frequently induce not only cellular T-cell responses but also humoral B-cell responses. We hypothesized that the presence of antigen-specific autoantibodies could be used as a “surrogate marker” for the identification of target T-cell autoantigens in AA patients. We screened a human fetal liver library for serologic reactivity against hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell antigens and isolated 32 genes. In 7 of 18 AA patients, an immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody response was detected to one of the genes, kinectin, which is expressed in all hematopoietic cell lineages tested including CD34+ cells. No response to kinectin was detected in healthy volunteers, multiply transfused non-AA patients, or patients with other autoimmune diseases. Epitope mapping of IgG autoantibodies against kinectin revealed that the responses to several of the epitopes were shared by different AA patients. Moreover, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells raised against kinectin-derived peptides suppressed the colony formation of granulocyte macrophage colony-forming units (CFU-GMs) in an HLA class I-restricted fashion. These results suggest that kinectin may be a candidate autoantigen that is involved in the pathophysiology of AA. (Blood. 2003;102:4567-4575)

Introduction

Three decades ago, an immune mechanism was first implicated in the pathogenesis of aplastic anemia (AA).1 Since then, accumulating evidence supports the hypothesis that immune mechanisms contribute to the pathogenesis of AA.2-4 Immunosuppressive therapies incorporating antithymocyte globulin, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and/or cyclophosphamide have been successfully used in the treatment of patients with AA with response rates ranging from 50% to 80%,5-9 suggesting that pancytopenia and bone marrow failure in at least some AA patients are immunologically mediated. Furthermore, in vitro studies have also supplied supportive evidence for an immune-mediated suppression of hematopoiesis in AA. These include inhibitory effects of AA patient lymphocytes on hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) growth,10,11 overproduction of myelosuppressive cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-gamma) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-alpha) by patient bone marrow cells,12-16 and an increased population of activated suppressor T cells.17-19 Taken together, these data suggest that at least some cases of AA involve autoimmune phenomena that target hematopoietic tissue, probably HSPCs.

By establishing T-cell lines or clones from an involved organ and analyzing their specificity, investigators have successfully identified unknown target antigens in organ-specific autoimmune diseases and neoplasms.20,21 Previous studies with T cells from AA patients have identified a pathogenic role for both CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Peripheral blood T cells capable of suppressing in vitro growth of HSPCs belong mainly to the CD8+ fraction.22,23 However, the importance of CD4+ cytotoxic T cells in the pathogenesis of AA has been also described. Several CD4+ T-cell clones that can lyse autologous hematopoietic cells in an HLA class II-restricted fashion have been isolated from AA patients.24

In organ-specific autoimmune diseases, autoreactive T-cell responses against target autoantigens play a major role in the disease pathogenesis. At the same time, these autoantigens can also evoke humoral responses (ie, immunoglobulin G [IgG] autoantibody production in many cases). For example, target autoantigens such as myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis and mitochondrial branched chain keto acid dehydrogenase complexes in primary biliary cirrhosis have been shown to induce both IgG production and CD4+ T-cell responses.20 In fact, even though a role for antibody-mediated tissue destruction may not be confirmed, in some cases investigators have first identified the humoral response to antigens that serve as the targets of pathologic autoreactive T cells.25 This approach is currently being explored in patients with cancer where serologic identification of antigens by recombinant expression cloning (SEREX) has been applied to the identification of tumor-associated antigens, and hundreds of candidate genes have been isolated.26-29 Importantly, some of the antigens like NY-ESO-1 originally identified by antibody reactivity have subsequently been shown to be targets of CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell responses in vivo.30,31

Based on these observations, we hypothesized that the target autoantigens recognized by CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells in patients with AA might also produce humoral response (ie, autoantibody production). The characterization of the autoantibodies to hematopoietic tissue, especially HSPCs, by SEREX technology could serve as a surrogate marker for autoantigen-specific T cells and might yield novel insights into the T cell-mediated pathophysiology of AA. Here, we describe the identification of novel autoantigens expressed by HSPCs in association with AA.

Patients, materials, and methods

Preparation of blood samples

Blood and bone marrow (BM) samples were obtained from 18 patients with AA, 20 multiply transfused patients with thalassemia and sickle cell anemia, 19 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), 24 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 22 patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), and 35 healthy volunteers enrolled in research protocols at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, and were immediately stored in aliquots at -80°C until use. All protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of the above institutions.

Identification of immunoreactive cDNA clones

Screening for candidate antigens was performed using a human fetal liver cDNA expression library (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) as described previously.32 Briefly, XL1-Blue Escherichia coli (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was transfected with recombinant phages, plated on agar plates, and cultured at 42°C. Expression of recombinant proteins was induced by incubating the bacterial lawns with an overlay of isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG)—impregnated nitrocellulose filters (Hybond C-Extra; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Transfer of released proteins was allowed to proceed at 37°C. To increase the solubility of the induced proteins, some of the filters were first treated with 8 M urea and subsequently with serially diluted urea to renature recombinant proteins. Filters were then washed in TBST (10 mM Tris [tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane], 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 8.0) and blocked overnight with blocking buffer (5% wt/vol nonfat dry milk [Nestle, Solon, OH] in TBST). Filters were then incubated with patient serum at 1:500. Specific binding of antibody to recombinant protein was detected by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat antihuman IgG antibody (Promega, Madison, WI) diluted at 1:7500 or goat antihuman Fc gamma antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) at 1:3000. Visualization of the antigen-antibody complex was accomplished by staining with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium (Promega). Complementary DNA inserts from positive clones were subcloned, purified, and in vivo excised to plasmid forms (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA inserts were subsequently sequenced with appropriate sequencing primers.

Phage plate assay

Each clone of interest was screened as described above by mixing the positive clone of interest with nonreactive phages from the cDNA library as an internal negative control at a ratio of approximately 1:10.

Expression and purification of bacterially expressed fusion proteins

Isolated cDNA inserts were subcloned in-frame into the pQE30 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and pGEX-5X3 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) vectors for His-tagged and GST (glutathione S-transferase) fusion protein expression, respectively. His-tagged or GST kinectin was constructed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based subcloning, and the sequence was verified. The induction and affinity purification of fusion proteins were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Appropriate size and specificity of the expressed protein products were confirmed by Western blot analysis using mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody (1:3000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-His monoclonal antibody (1:3000; Sigma, St Louis, MO), or mouse antikinectin monoclonal antibody (1:10 000) (a gift from Dr I. Toyoshima, Akita University School of Medicine).

Western blot analysis

Both purified proteins and bacterial lysates were prepared in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer. Equal amounts of protein were analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA), and incubated with blocking buffer overnight. Immunoblots were performed with 1:500 or indicated dilution of patient serum, mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody, mouse anti-His monoclonal antibody, or mouse antikinectin monoclonal antibody. Immunodetection was performed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antihuman IgG (1:10 000; Promega) or antimouse IgG secondary antibody (1:5000; Promega) as indicated by the host origin of the primary antibody and developed by chemiluminescence (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA).

ELISA assay

Recombinant His-tagged kinectin protein encoding amino acids (aa) 434-1008 was produced and purified as described above. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plates were coated with purified recombinant protein at 1 μg/mL in coating buffer (50 mM carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6) overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed and blocked overnight at 4°C with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST. Patient sera were added to a final dilution of 1:500 to 1:5000 and incubated at room temperature. After wash, the plates were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat antihuman IgG antibody (1:7500; Promega) at room temperature. Finally, the plates were washed and incubated with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) at room temperature, and the optic density (OD) (405 nm) was read (Spectramax 190 Microplate Reader; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A positive reaction was defined as an absorbance value exceeding the mean OD absorbance value of sera from healthy donors by 3 standard deviations.

HLA-A*0201-binding assay

Peptide prediction was performed using publicly available algorithms.33 Transporter associated with antigen-processing (TAP)-deficient T2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were pulsed with 50 μg/mL peptide and 5 μg/mL β2-microglobulin (CalBiochem, San Diego, CA) for 18 hours at 37°C. HLA-A*0201 expression was then measured by flow cytometry using HLA-A2-specific monoclonal antibody (MoAb) BB7.2 (American Type Culture Collection) followed by incubation with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat antimouse Ig (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA).

Establishment of cytotoxic T cells against kinectin-derived peptides

Cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) against kinectin-derived peptides were established according to a protocol described previously.34 Briefly, purified CD8+ T cells from HLA-A2-positive healthy donors were repeatedly stimulated with autologous peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and CD40L-activated B cells, and the standard cytotoxicity assay was performed using peptide-pulsed T2 cells.

Hematopoietic progenitor cell assay

CD34+ cells were purified from HLA-A2-positive BM cells using a CD34+ cell isolation kit (Dynal, Lake Success, NY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Freshly isolated CD34+ cells were mixed with CTLs against kinectin-derived peptides, 645F and 794S, at 50:1 ratio and incubated at 37°C in a 96-well U-bottomed plate; 10 μg/mL of HLA-A2-specific BB7.2 MoAb (mouse IgG2b) was preincubated with CD34+ cells at 37°C for 30 minutes to block cytotoxicity by T cells as indicated. After 16 hours, the cell suspension was added with the methylcellulose medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) supplemented with colony-stimulating factors, and 1 × 103 CD34+ cells were plated on a 35-mm culture dish. After 12 to 14 days, granulocyte macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-GM)-derived colonies and erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E)-derived colonies were counted under an inverted microscope. Similar experiments were performed 3 times in an at least sextuplicated manner.

Results

Serologic identification of autoantigens in AA patient sera

We performed a serologic screen to identify candidate target autoantigens in AA. We screened for HSPC antigens by using a human fetal liver cDNA library, because this organ contains a high proportion of cells derived from HSPCs. Also, we limited our screening to those genes that elicit IgG responses, because our aim was to identify potential autoantigens that are targets of T cells and production of IgG usually requires CD4+ T cell-driven class switching. We screened more than 2 × 106 phage plaques with diluted sera from each of 8 AA patients and identified 32 candidate genes including 10 expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and previously unknown genes (Table 1). Lineage-specific expression was determined by searching several available databases, including the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) UniGene database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/UniGene/), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Hembase database (http://hembase.niddk.nih.gov/), the Kazusa Human cDNA Project HUGE database (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/huge/), and the Blood SAGE database (http://bloodsage.gi.k.utokyo.ac.jp/).35-37 Our search revealed that 17 of the 22 immunoreactive candidate genes are expressed by hematopoietic cells, and their predominant lineage expression is also listed in Table 1. Also, the expression of these genes by CD34+ cells was indicated by searching the UniGene databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/UniGene/library.cgi?ORG=Hs&LID=933/ and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov:80/UniGene/library.cgi?ORG=Hs&LID=1537), the Westbrook Lab at University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) hematopoietic stem cell database (http://westsun.hema.uic.edu/html/expression.html), the rzdp database (http://www.rzpd.de/cgi-bin/services/exp/viewExpressionData.pl.cgi/), and published data by Mao et al.38-41 The remaining 5 genes were expressed by liver and are listed in Table 1 as “Genes not reported to be expressed by hematopoietic cells.” Of the 32 total genes identified, we focused our analysis on the 22 genes previously described. Using the phage plate assay, we confirmed the reactivity of 8 AA patients' sera against these genes (Table 1).

Genes isolated by serologic screening with 8 AA patient's sera

Genes . | Positivity by phage plaque assay . | Lineage distribution . | Expression in CD34+ cells . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genes expressed by hematopoietic cells (UniGene cluster ID) | |||

| Kinectin (Hs.418467) | 4 of 8 | M, E, L | + |

| RhoB (Hs.406064) | 2 of 8 | M, L | − |

| Sorbitol dehydrogenase (Hs.878) | 2 of 8 | E | + |

| Ribosomal protein S3A (Hs.77039) | 2 of 8 | M, E, L | + |

| Tropomyosin 2 (Hs.300772) | 2 of 8 | L | + |

| H-ferritin (Hs.418650) | 1 of 8 | M, E | − |

| PGR 1 (ND) | 1 of 8 | ND | − |

| Hsp90-alpha (Hs.356531) | 1 of 8 | M, L | + |

| S100A9, MRP14 (Hs.112405) | 1 of 8 | M | + |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein (Hs.324746) | 1 of 8 | E | − |

| Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.2 (Hs.733) | 1 of 8 | E | − |

| Globin gamma A (Hs.283108) | 1 of 8 | E | + |

| Globin beta (Hs.155376) | 1 of 8 | E | + |

| RBQ-1 (Hs.91065) | 1 of 8 | L | + |

| Nuclease sensitive element-binding protein I (Hs. 74497) | 1 of 8 | E | + |

| Methionine aminopeptidase 1 (Hs.82007) | 1 of 8 | M, L | + |

| Hook1 (Hs.250752) | 1 of 8 | E | − |

| Genes not reported to be expressed by hematopoietic cells | |||

| Alcohol dehydrogenase alpha subunit | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Aldolase B | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Group-specific component | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Apolipoprotein A-II | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Serum albumin | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| ESTs, unknown genes | ND | NA | NA |

Genes . | Positivity by phage plaque assay . | Lineage distribution . | Expression in CD34+ cells . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genes expressed by hematopoietic cells (UniGene cluster ID) | |||

| Kinectin (Hs.418467) | 4 of 8 | M, E, L | + |

| RhoB (Hs.406064) | 2 of 8 | M, L | − |

| Sorbitol dehydrogenase (Hs.878) | 2 of 8 | E | + |

| Ribosomal protein S3A (Hs.77039) | 2 of 8 | M, E, L | + |

| Tropomyosin 2 (Hs.300772) | 2 of 8 | L | + |

| H-ferritin (Hs.418650) | 1 of 8 | M, E | − |

| PGR 1 (ND) | 1 of 8 | ND | − |

| Hsp90-alpha (Hs.356531) | 1 of 8 | M, L | + |

| S100A9, MRP14 (Hs.112405) | 1 of 8 | M | + |

| Alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein (Hs.324746) | 1 of 8 | E | − |

| Erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.2 (Hs.733) | 1 of 8 | E | − |

| Globin gamma A (Hs.283108) | 1 of 8 | E | + |

| Globin beta (Hs.155376) | 1 of 8 | E | + |

| RBQ-1 (Hs.91065) | 1 of 8 | L | + |

| Nuclease sensitive element-binding protein I (Hs. 74497) | 1 of 8 | E | + |

| Methionine aminopeptidase 1 (Hs.82007) | 1 of 8 | M, L | + |

| Hook1 (Hs.250752) | 1 of 8 | E | − |

| Genes not reported to be expressed by hematopoietic cells | |||

| Alcohol dehydrogenase alpha subunit | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Aldolase B | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Group-specific component | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Apolipoprotein A-II | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| Serum albumin | 1 of 8 | NA | NA |

| ESTs, unknown genes | ND | NA | NA |

M indicates myeloid; E, erythroid; L, lymphoid; ND, not determined; NA, not applicable.

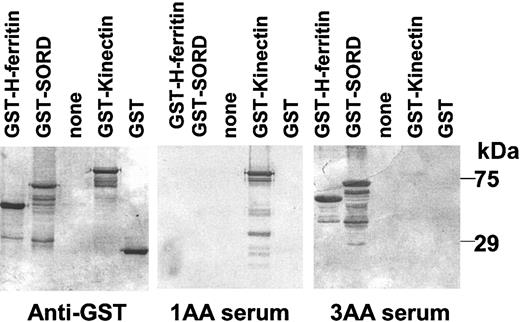

To confirm patient sera reactivity with protein products of candidate AA genes, we produced GST fusion proteins from isolated clones and performed Western blot analysis using AA patient sera. Figure 1 shows representative results of the Western blot analysis. Here, serum from patient 1AA specifically detects kinectin but not GST alone, sorbitol dehydrogenase (SORD), or H-ferritin. On the other hand, the serum from patient 3AA does not detect kinectin or GST alone, although it does detect H-ferritin and SORD.

Representative Western blot analysis of cloned gene protein products using anti-GST monoclonal antibody and sera from 2 AA patients. GST fusion proteins were induced by IPTG, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes. Triplicates of membranes were prepared and probed with mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody, patient 1AA serum, or patient 3AA serum. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse or human IgG secondary antibody.

Representative Western blot analysis of cloned gene protein products using anti-GST monoclonal antibody and sera from 2 AA patients. GST fusion proteins were induced by IPTG, separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes. Triplicates of membranes were prepared and probed with mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody, patient 1AA serum, or patient 3AA serum. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse or human IgG secondary antibody.

Kinectin is expressed by hematopoietic cells at the protein level

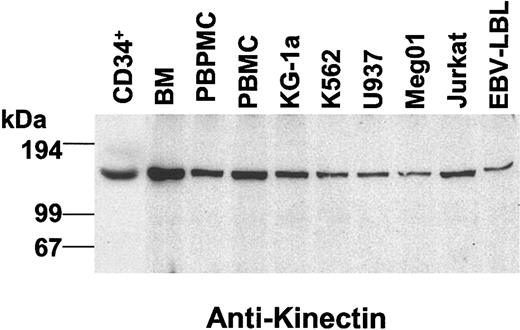

Initial screening using both the phage plate assay and Western blot analysis demonstrated a kinectin-induced IgG antibody response in 4 of 8 AA patients (Table 1). Given this high frequency, we next focused our studies on the association of antikinectin autoantibodies with AA. Kinectin is an intracellular protein of 160 kDa expressed in brain, testis, ovary, fetus, liver, and hematopoietic cells. Little is known about the function of kinectin other than that it is a kinesin-binding protein required for kinesin-based motility.42 Expression of kinectin by hematopoietic cells at the protein level was confirmed by Western blot analysis using a mouse antikinectin antibody (Figure 2). As shown, purified CD34+ cells, BM cells, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), and peripheral blood polymorphonuclear cells (PBPMCs) express kinectin protein. Cell lines derived from myeloid (KG1a), erythroid (K562), monocytoid (U937), megakaryocytoid (Meg01), and lymphoid cells (Jurkat and EBV-LBL) are also all positive for kinectin at the protein level (Figure 2). These results confirmed that kinectin is expressed by hematopoietic cells and suggested that kinectin could serve as an AA-associated antigen.

Expression of human kinectin in hematopoietic cells and cell lines. Equal amounts (25 μg) of total lysates were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF filters, and probed with mouse antikinectin monoclonal antibody. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG secondary antibody.

Expression of human kinectin in hematopoietic cells and cell lines. Equal amounts (25 μg) of total lysates were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF filters, and probed with mouse antikinectin monoclonal antibody. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse IgG secondary antibody.

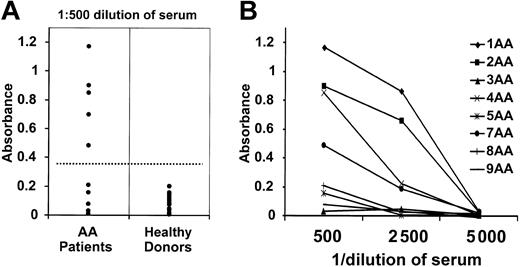

IgG antibody against kinectin can be detected by ELISA and Western blot analysis

To determine the prevalence of IgG antibodies directed against kinectin in AA patients, we performed an ELISA using a recombinant kinectin protein. Our initial serologic screen identified 2 partial kinectin cDNAs encoding different regions of the kinectin protein, aa 434-927 and 535-1008. We therefore expressed and purified a His-tagged partial kinectin cDNA encoding aa 434-1008. Representative ELISA results with sera (1:500 dilution) from 12 AA patients and 16 healthy donors are shown in Figure 3A. A positive reaction is defined as an absorbance value exceeding the mean absorbance value of sera from healthy donors by 3 standard deviations. Five of 12 AA patients showed a higher titer for IgG antibody against kinectin than did healthy volunteers. We also performed serial dilution experiments, and 2 of the 5 positive sera remain positive even at the dilution of 1:2500. In Figure 3B, we show the representative titration curves of serially diluted sera from 8 AA patients.

Representative ELISA results. (A) ELISA reactivities of sera from 12 AA patients and 16 healthy donors against purified His-tagged kinectin were measured at a 1:500 dilution. A positive reaction is defined as an absorbance value exceeding the mean OD absorbance value of sera from healthy donors by 3 SDs. (B) Sera from 8 AA patients were serially diluted, and ELISA reactivities were measured against purified His-tagged kinectin.

Representative ELISA results. (A) ELISA reactivities of sera from 12 AA patients and 16 healthy donors against purified His-tagged kinectin were measured at a 1:500 dilution. A positive reaction is defined as an absorbance value exceeding the mean OD absorbance value of sera from healthy donors by 3 SDs. (B) Sera from 8 AA patients were serially diluted, and ELISA reactivities were measured against purified His-tagged kinectin.

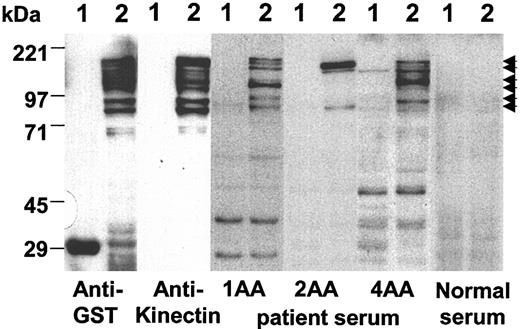

To explore the possibility that antibodies present in sera from AA patients recognize other regions of the kinectin protein, we produced a recombinant full-length kinectin protein fused to GST and then performed Western blot analysis using sera from all AA patients and healthy donors (Figure 4). Lysates expressing GST alone were loaded in each lane marked “1,” while GST-kinectin fusion protein lysates were loaded in each lane marked “2.” Anti-GST monoclonal antibody detected both the 29-kDa GST protein and the 190-kDa GST-kinectin fusion protein. The ladder pattern was probably due to alternative translation, initiation, and premature termination of translation rather than protein degradation, because the ladder pattern was reproducible with different preparations of the fusion proteins (data not shown). Also, we demonstrated that the antikinectin monoclonal antibody recognized the GST-kinectin fusion protein but not the GST moiety. Likewise, ELISA-positive AA sera, but not healthy-donor sera, detected the recombinant kinectin protein, confirming the results obtained by ELISA (Figures 4, 5). The positive pattern indicated by the arrows in Figure 4 differed somewhat between patients, suggesting that the antigenic epitopes recognized by AA patients might differ (Figure 6).

Sera from AA patients show different positive patterns for recombinant GST-full-length kinectin protein on Western blot analysis. Equal amounts of bacterial lysates expressing GST (lane 1) and GST-full-length kinectin fusion protein (lane 2) were separated by 9% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF filters, and probed with mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody, antikinectin monoclonal antibody, AA patient sera, or normal sera. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse or antihuman IgG secondary antibody. Arrows indicate the immunoreactive GST-kinectin fusion proteins.

Sera from AA patients show different positive patterns for recombinant GST-full-length kinectin protein on Western blot analysis. Equal amounts of bacterial lysates expressing GST (lane 1) and GST-full-length kinectin fusion protein (lane 2) were separated by 9% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF filters, and probed with mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody, antikinectin monoclonal antibody, AA patient sera, or normal sera. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antimouse or antihuman IgG secondary antibody. Arrows indicate the immunoreactive GST-kinectin fusion proteins.

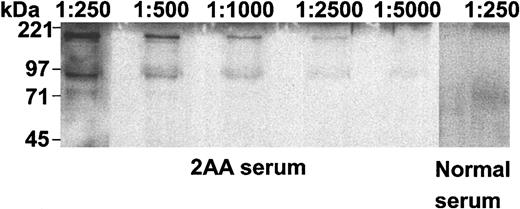

Sensitivity of 2AA patient serum reactivity against GST-kinectin fusion protein. Equal amounts of bacterial lysates containing GST-full-length kinectin fusion proteins were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF filters, and probed with patient 2AA sera (diluted at 1:250 to 1:5000) or normal serum diluted at 1:250. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antihuman secondary antibody.

Sensitivity of 2AA patient serum reactivity against GST-kinectin fusion protein. Equal amounts of bacterial lysates containing GST-full-length kinectin fusion proteins were separated by 7.5% SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF filters, and probed with patient 2AA sera (diluted at 1:250 to 1:5000) or normal serum diluted at 1:250. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antihuman secondary antibody.

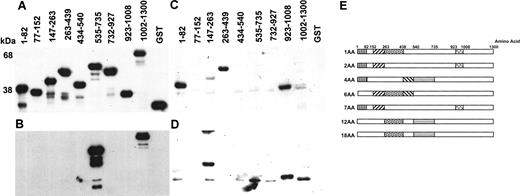

Partial epitope mapping of kinectin IgG autoantibody using GST-kinectin fusion proteins. We made a series of GST-partial kinectin fusion proteins using PCR-based subcloning. Equal amounts of lysates expressing various different fusion proteins were separated by 9% SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed. Blots were probed with mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody (A), antikinectin monoclonal antibody (B), patient 1AA serum (C), or patient 7AA serum (D). Immunoreactive proteins were detected as described in previous figures. (E) Results of partial epitope mapping of kinectin IgG autoantibody in 6 AA patients' sera are shown. Regions of the kinectin sequence shaded with identical patterns represent areas that are immunoreactive with multiple AA patient sera.

Partial epitope mapping of kinectin IgG autoantibody using GST-kinectin fusion proteins. We made a series of GST-partial kinectin fusion proteins using PCR-based subcloning. Equal amounts of lysates expressing various different fusion proteins were separated by 9% SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed. Blots were probed with mouse anti-GST monoclonal antibody (A), antikinectin monoclonal antibody (B), patient 1AA serum (C), or patient 7AA serum (D). Immunoreactive proteins were detected as described in previous figures. (E) Results of partial epitope mapping of kinectin IgG autoantibody in 6 AA patients' sera are shown. Regions of the kinectin sequence shaded with identical patterns represent areas that are immunoreactive with multiple AA patient sera.

Antikinectin autoantibody is frequently detected in AA patients but not in healthy donors, multiply transfused non-AA patients, or patients with other autoimmune diseases

We extended our screening to a total of 18 AA patients and 35 healthy volunteers for antikinectin autoantibody production. We found that 7 of 18 AA patients had IgG antibodies directed against kinectin by ELISA or Western blot analysis, whereas all healthy volunteers were negative (Table 2). Results of ELISA and Western blot analysis were concordant in all cases except one AA patient, in whom the discrepancy may be due to differences in the antigenicity of the recombinant kinectin proteins used in the 2 assays. We also investigated the possibility that antikinectin autoantibody production was a consequence of transfusion-related allogeneic immune responses by testing sera from patients who had received multiple transfusions. We did not detect any antikinectin antibody in any of the 20 multiply transfused patients who had either thalassemia or sickle cell anemia (Table 2). Furthermore, sera from 65 patients with other autoimmune diseases, SLE, RA, and MS, lacked the presence of antikinectin antibody, suggesting the possible specificity of antikinectin autoantibody production in AA patients (Table 2).

Survey of sera from 35 healthy donors and 18 AA, 20 multiply transfused, and 65 non-AA autoimmune disease patients: reactivity with recombinant kinectin protein

. | Western blot analysis . | ELISA . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy donors | 0 of 35* | 0 of 35 |

| AA patients | 7 of 18* | 6 of 18 |

| Multiply transfused patients with thalassemia and sickle cell anemia | 0 of 20 | 0 of 20 |

| Non-AA autoimmune disease patients: 19 SLE, 24 RA, 22 MS | NT | 0 of 65 |

. | Western blot analysis . | ELISA . |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy donors | 0 of 35* | 0 of 35 |

| AA patients | 7 of 18* | 6 of 18 |

| Multiply transfused patients with thalassemia and sickle cell anemia | 0 of 20 | 0 of 20 |

| Non-AA autoimmune disease patients: 19 SLE, 24 RA, 22 MS | NT | 0 of 65 |

NT indicates not tested.

P<.001 compared with AA patients by the χ2 method.

Lack of association of preceding hepatitis or transfusion with antikinectin autoantibody positivity in patients with AA

In Table 3 we provide a summary of the characteristics of AA patients studied for kinectin IgG autoantibodies. The data here do not support that autoantibody production is a result of transfusions or hepatitis. It is well known that, in some cases, AA is preceded by an episode of hepatitis. Potential induction of an antikinectin antibody response to hepatitis is unlikely given the fact that 5 of 6 positive patients did not have a history of preceding hepatitis (Table 3). Furthermore, while most AA patients had been transfused prior to enrollment on this study, 1 antikinectin-positive AA patient did not have a history of transfusion, and another antikinectin-positive patient received the first transfusion immediately prior to blood sampling. Therefore, it is unlikely that either of these patients developed antikinectin antibodies as a result of transfusion. These facts further support the hypothesis that the production of antikinectin autoantibodies in AA patients is not due to preceding hepatitis or an allogeneic reaction to transfused blood products.

Characteristics of AA patients studied

Age, y/sex . | Type of AA . | Preceding hepatitis . | Blood transfusion . | Immunosuppressive therapy before sampling . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antikinectin IgG antibody-positive | ||||

| 18/F | Moderate | − | − | + |

| 48/M | Severe | + | ±* | − |

| 12/M | Severe | − | + | + |

| 18/F | Moderate | − | + | + |

| 9/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| 13/M | Severe | − | + | + |

| 57/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| Antikinectin IgG antibody-negative | ||||

| 3/F | Moderate/severe | − | − | − |

| 15/F | Severe | − | − | − |

| 11/M | Moderate/severe | − | − | + |

| 24/F | Moderate/severe | − | + | − |

| 9/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| 56/F | Moderate | − | + | − |

| 0/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | − |

| 3/F | Moderate | − | + | + |

| 15/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| 33/M | Severe | + | + | − |

| 38/M | Moderate/severe | + | + | + |

Age, y/sex . | Type of AA . | Preceding hepatitis . | Blood transfusion . | Immunosuppressive therapy before sampling . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antikinectin IgG antibody-positive | ||||

| 18/F | Moderate | − | − | + |

| 48/M | Severe | + | ±* | − |

| 12/M | Severe | − | + | + |

| 18/F | Moderate | − | + | + |

| 9/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| 13/M | Severe | − | + | + |

| 57/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| Antikinectin IgG antibody-negative | ||||

| 3/F | Moderate/severe | − | − | − |

| 15/F | Severe | − | − | − |

| 11/M | Moderate/severe | − | − | + |

| 24/F | Moderate/severe | − | + | − |

| 9/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| 56/F | Moderate | − | + | − |

| 0/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | − |

| 3/F | Moderate | − | + | + |

| 15/M | Moderate/severe | − | + | + |

| 33/M | Severe | + | + | − |

| 38/M | Moderate/severe | + | + | + |

This patient received his first blood transfusion immediately prior to blood sampling.

Some of the B-cell epitope regions of kinectin IgG autoantibodies were shared by AA patients

We postulated that kinectin may contain immunogenic “hot spots” that are recognized by multiple patient sera. We believed that such information might help identify potential T-cell epitopes, because IgG autoantibodies sometimes recognize amino acid sequences that are also recognized by T cells in some autoimmune diseases.43,44 To do this, we determined the kinectin epitope sequences recognized by patient sera. We investigated the antigenic epitopes of kinectin IgG antibodies using a GST fusion system. Using a PCR-based subcloning method, we made a series of 8 GST-partial kinectin fusion proteins. Fusion proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and Western blot analysis was performed. A blot with anti-GST antibody (Figure 6A) verified the presence of equal molar amounts of 8 different GST-kinectin fusion proteins. A blot with mouse antikinectin antibody (Figure 6B) indicated that this antibody could recognize 2 regions of the kinectin protein present on aa 535-735 and aa 1002-1300. B lots performed with 2 different AA patient sera show that aa 923-1008 was recognized by both patient 1AA (Figure 6C) and 7AA (Figure 6D) sera, while fusion protein aa 263-439 was recognized by patient 1AA but not patient 7AA serum. Figure 6E summarizes the results of partial IgG epitope mapping of kinectin IgG antibodies in 7 AA patients. The boxes with the same pattern indicate regions that were recognized by more than one patient. As illustrated, several epitopes are shared by multiple patients while others are not.

Kinectin-derived peptides bind HLA-A2 molecules

Because the antibody response against kinectin in AA patients is an IgG response, CD4+ T-cell involvement was strongly suggested. We were also interested in exploring whether a CD8+ T-cell response against kinectin could be generated. First, we attempted to determine if kinectin-derived peptides could be presented by HLA class I molecules. A peptide-motif scoring system (http://bimas.dcrt.nih.gov/molbio/hla_bind/) was used to predict possible kinectin-derived peptides for HLA-A2. Four kinectin-derived peptide sequences recorded high scores for A2 binding compared with the peptides known to bind A2, consistent with the possibility that these predicted peptides might bind HLA-A2 (Table 4). These peptides were pulsed with β2-microglobulin onto the HLA-A*0201-positive T2 hybridoma in a standard functional peptide-binding assay. Based on increased expression of HLA-A*0201 on pulsed T2 cells, 2 of the 4 kinectin-derived peptides were found to bind strongly to HLA-A*0201 (Table 4). A positive control peptide derived from the tumor antigen MAGE-3 also bound strongly, but 2 negative control peptides did not.

Binding of kinectin-derived peptides and controls to HLA-A*0201

Name . | Sequence . | Protein . | Position . | Score* . | Fluorescence index† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 794S | SLVEELKKV | Kinectin | aa 794 | 656 | 2.8 |

| 645F | FLLKAEVQKL | Kinectin | aa 645 | 836 | 1.5 |

| 600V | VLAEELHKV | Kinectin | aa 600 | 1115 | 0.6 |

| 553Q | ALMESEQKV | Kinectin | aa 552 | 1055 | 0.3 |

| F271 | FLWGPRALV (positive control) | MAGE-3 | aa 271 | 2655 | 2.0 |

| A98-Id‡ | AHTKDGFNF (negative control) | Idiotype | aa 98 | 0 | 0.1 |

Name . | Sequence . | Protein . | Position . | Score* . | Fluorescence index† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 794S | SLVEELKKV | Kinectin | aa 794 | 656 | 2.8 |

| 645F | FLLKAEVQKL | Kinectin | aa 645 | 836 | 1.5 |

| 600V | VLAEELHKV | Kinectin | aa 600 | 1115 | 0.6 |

| 553Q | ALMESEQKV | Kinectin | aa 552 | 1055 | 0.3 |

| F271 | FLWGPRALV (positive control) | MAGE-3 | aa 271 | 2655 | 2.0 |

| A98-Id‡ | AHTKDGFNF (negative control) | Idiotype | aa 98 | 0 | 0.1 |

Calculated score in arbitrary units.

(Mean fluorescence with peptide-mean fluorescence without peptide)/(mean fluorescence without peptide).

Peptide sequence obtained from the idiotypic sequence of a patient with plasma cell leukemia and predicted to bind to HLA-B38.

T-cell repertoire against kinectin-derived peptides is preserved in healthy donors

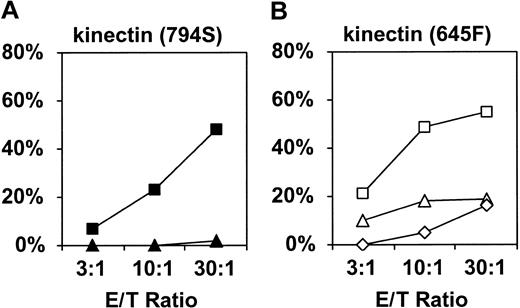

To investigate whether the peripheral blood from healthy donors contains cytotoxic T-cell precursors against kinectin, we established CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) against kinectin-derived peptides from healthy donors. Purified CD8+ T cells from A2-positive healthy donors were repeatedly stimulated with autologous peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and CD40L-acivated B cells, and the standard cytolysis assay was performed using T2 cells. CTLs against kinectin-derived peptides 794S (Figure 7A) and 645F (Figure 7B) specifically killed the target cells pulsed with each of the peptides. We succeeded in raising CTLs against kinectin-derived peptides from the peripheral blood of 2 of 3 HLA-A2-positive healthy donors tested. These results support the assertion that T-cell repertoire against kinectin-derived peptides is present in healthy individuals.

Standard cytotoxicity assay. We raised CTLs against kinectin-derived peptides 794S (A) and 645F (B) from healthy donors. Peptide-pulsed T2 cells were incubated with differing E/T ratios in a 4-hour cytotoxicity assay. (A) CTLs raised against the 794S peptide specifically lyse 794S pulsed (▪) but not T2 cells pulsed with an irrelevant peptide (▴, F271 from MAGE-3). (B) Similarly, CTLs generated against the 945F peptide recognize only T2 cells pulsed with 645F (□) but not control T2 cells (▵, pulsed with F271; ⋄, unpulsed).

Standard cytotoxicity assay. We raised CTLs against kinectin-derived peptides 794S (A) and 645F (B) from healthy donors. Peptide-pulsed T2 cells were incubated with differing E/T ratios in a 4-hour cytotoxicity assay. (A) CTLs raised against the 794S peptide specifically lyse 794S pulsed (▪) but not T2 cells pulsed with an irrelevant peptide (▴, F271 from MAGE-3). (B) Similarly, CTLs generated against the 945F peptide recognize only T2 cells pulsed with 645F (□) but not control T2 cells (▵, pulsed with F271; ⋄, unpulsed).

Inhibition of CFU-GM-but not BFU-E-derived colony formation by CTLs against kinectin-derived peptide 645F

If a CD8+ T-cell response against a candidate autoantigen is involved in the pathogenesis of AA, the autoantigen-derived peptides should be presented by HLA class I molecules on target cells, namely HSPCs in AA. Therefore, we used the cytotoxicity assay to study whether HSPCs can naturally process and present kinectin-derived peptides 645F and 794S via HLA-A2 molecules. HLA-A2-positive CD34+ cells were incubated with CTLs raised against kinectin-derived peptides, 645F and 794S, and were then cultured in methylcellulose medium supplemented with colony-stimulating factors. CTLs against 645F inhibited CFU-GM-derived colony formation in an HLA-A2-specific fashion but not BFU-E-derived colony formation (Table 5). In contrast, CTLs against 794S did not suppress either CFU-GM- or BFU-E-derived colony formation. CTLs were simultaneously and similarly made from the same donor and inhibited CFU-GM colony formation only when raised against 645F but not against 794S. Therefore, these results are peptide/HLA specific and are not due to allogeneic effects. Because these data show that kinectin-derived 645F is naturally processed and presented by CFU-GMs via HLA-A2 molecules, we propose that kinectin-derived peptide may be involved in the suppression of CFU-GM colony formation seen in some AA patients. Notably, 645F, but not 794S, is located in one of the B-cell epitope hot spots identified. Intriguingly, this is analogous to other autoimmune diseases, where IgG autoantibodies recognize amino acid sequences that are also recognized by target T cells.20,43,44

Effect of CTLs against kinectin-derived peptide on colony formation by CD34+ cells

Experiment . | CTLs against kinectin peptide . | Blocking MoAb . | CFU-GM . | BFU-E . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | None | 48 ± 4 | 22 ± 2 |

| 645F | None | 26 ± 2 | 24 ± 4 | |

| 645F | mlgG2b | 25 ± 3 | 26 ± 3 | |

| 645F | BB7.2 | 48 ± 3 | 27 ± 2 | |

| 794S | None | 44 ± 3 | 25 ± 2 | |

| 794S | mlgG2b | 48 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 794S | BB7.2 | 49 ± 4 | 24 ± 3 | |

| 2 | None | None | 64 ± 5 | 22 ± 2 |

| 645F | None | 36 ± 5 | 25 ± 2 | |

| 645F | mlgG2b | 38 ± 2 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 645F | BB7.2 | 68 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 794S | None | 68 ± 3 | 24 ± 5 | |

| 794S | mlgG2b | 69 ± 5 | 24 ± 3 | |

| 794S | BB7.2 | 71 ± 5 | 24 ± 4 |

Experiment . | CTLs against kinectin peptide . | Blocking MoAb . | CFU-GM . | BFU-E . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | None | 48 ± 4 | 22 ± 2 |

| 645F | None | 26 ± 2 | 24 ± 4 | |

| 645F | mlgG2b | 25 ± 3 | 26 ± 3 | |

| 645F | BB7.2 | 48 ± 3 | 27 ± 2 | |

| 794S | None | 44 ± 3 | 25 ± 2 | |

| 794S | mlgG2b | 48 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 794S | BB7.2 | 49 ± 4 | 24 ± 3 | |

| 2 | None | None | 64 ± 5 | 22 ± 2 |

| 645F | None | 36 ± 5 | 25 ± 2 | |

| 645F | mlgG2b | 38 ± 2 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 645F | BB7.2 | 68 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | |

| 794S | None | 68 ± 3 | 24 ± 5 | |

| 794S | mlgG2b | 69 ± 5 | 24 ± 3 | |

| 794S | BB7.2 | 71 ± 5 | 24 ± 4 |

Representative results of 3 similar experiments performed in an at least sextuplicated manner. Data are represented as means ± SD. BB7.2 indicates HLA-A2-specific MoAb; mlgG2b, isotype control.

Discussion

Organ-specific autoantigens in T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases have been shown to be targets of not only pathologic cellular responses but also humoral responses (ie, autoantibody production).20 The initial identification of a humoral immune response to the target antigen sometimes precedes the confirmation of a pathologic T-cell immune response to the same antigen. Because, in some cases, AA is a T cell-mediated autoimmune disease, we reasoned that the pathologic immune response in AA might include both antigen-specific T-cell and autoantibody production. Although this humoral immune response itself may not be directly involved in the pathophysiology of AA, the presence of antigen-specific autoantibodies can be used as a “surrogate marker” to identify T-cell target autoantigens in AA patients. In this study we demonstrated that some AA patients have a robust humoral immune response that recognizes multiple autoantigenic proteins expressed by hematopoietic and/or liver cells.

Serologic screening of a fetal liver library with sera from 8 AA patients revealed more than 30 potential AA-specific candidate autoantigens. The choice of a human fetal liver cDNA library, which is highly enriched for CD34+ cells, compared with peripheral blood or bone marrow, significantly increased the likelihood that we would detect possible HSPC autoantigens. We also reasoned that the selection of fetal liver for our cDNA library might also increase our capacity to detect antigens that could be shared by hepatocytes and HSPCs. This concept was particularly attractive given published evidence that some cases of AA are preceded by hepatitis.2,45,46 Theoretically, AA-associated liver inflammation and tissue destruction might evoke a strong immune response directed against antigens shared by both liver and hematopoietic cells. Further investigation is needed to determine whether any of the identified candidate AA autoantigens are involved in the hepatitis-associated AA.

Of the multiple candidate autoantigens identified, ELISA and Western blot analysis revealed that an IgG antibody response to one of the candidate autoantigens, kinectin, was present in a significant number of AA patients (39%). In contrast, no antibody was detected in 35 healthy volunteers or in 20 patients with thalassemia or sickle cell anemia who had a history of multiple transfusions. Also, antibody was detected in both transfused and transfusion-naive AA patients, suggesting that antikinectin autoantibody development was not simply due to transfusion-related alloreactivity. Moreover, the clinical histories of these patients do not support an association of antikinectin reactivity with AA-associated hepatitis. Negative studies of sera from patients with the autoimmune diseases SLE, RA, and MS further defined the specific association of antikinectin responses with AA. These results support the hypothesis that an immune response to kinectin is restricted to patients with AA and may be involved in the pathophysiology of this disease.

We postulated that at least some of the identified candidate autoantigens are the targets of a cytolytic T-cell response in patients with AA. Because kinectin is a large molecule comprising 1300 aa,42 it is likely that several kinectin-derived peptides are processed and presented in the context of HLA molecules to T cells. It has been shown that other examples of immunologic antigens, such as the H-Y minor histocompatibility antigens, can be processed and presented by multiple HLA class I alleles. One of the H-Y antigens, SMCY, is a large molecule with 1539 aa and has been demonstrated to be processed and presented via both HLA-A2 and B7 molecules.47,48 Another H-Y antigen, known as UTY, is also a large molecule with 1186 aa, and its peptide epitopes can be presented via both HLA-B8 and -B60.49,50 These examples show that large molecules, like kinectin, can be naturally processed and presented via multiple HLA class I alleles and can induce multiple antigen-specific CD8 T-cell responses. In this report, we demonstrated that kinectin is expressed by CD34+ cells and that kinectin-derived 645F peptide can be naturally processed and presented by HLA-A2 molecules on CFU-GMs but not on BFU-Es. Because kinectin is likely to contain multiple peptide epitopes that are processed and presented to T cells, it is possible that epitopes other than 645F or 794S are presented by BFU-Es and are involved in the suppression of BFU-E-specific colony formation in vivo. Attempts to identify such epitopes are currently ongoing. The probability that kinectin-derived peptide epitopes can be processed and presented by multiple HLA alleles provides insight into why kinectin may serve as a target autoantigen in many AA patients of various different HLA types.

In addition to their expression in human hematopoietic cells, kinectin transcripts have also been found in human liver, ovary, testis, and brain.42 If human HSPCs are the target of kinectin-specific autoreactive T cells in AA patients, why then are these other tissues spared from attack by antikinectin-specific autoreactive T cells? For T cells to recognize specific peptides derived from an antigen, that antigen must be expressed at the protein level and then must be processed and presented via HLA molecules. We suggest that kinectin-derived peptides may be processed and presented by HLA complexes present on human HSPCs but not by those expressed in other kinectin-positive tissue. It has been shown that antigen-processing systems in different tissues may differ in what peptides are processed and presented. An example is again provided by the H-Y antigens encoded by the SMCY and UTY genes. Although transcripts of these genes are detected in a wide variety of human tissues, only human hematopoietic cells such as phytohemagglutinin (PHA) blasts and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells serve as targets of T cells directed against H-Y antigens.50 An additional explanation for the protection of other kinectin-positive tissues from damage by autoreactive T cells also might include expression of kinectin by tissues such as testis and brain that are privileged sanctuaries that exclude T-cell migration.

This study confirms that humoral immune responses to hematopoietic antigens can be detected in AA patients. As in other autoimmune diseases, these humoral immune responses may be useful in unraveling the disease pathophysiology of AA. Therefore, we are embarking on a prospective study to help delineate the role of these immune responses in the pathophysiology of AA and to examine whether these findings can translate into improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of AA.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 28, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3409.

Supported by a Translational Research Award by the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (J.L.S.), P50-HL-54785 and P01-AI-41584 (E.C.G.), and P01-CA-66996 and P01-CA-78378 (L.M N.). N.H. was supported by the Sankyo Foundation of Life Science. M.O.B. is supported by K08-CA-87720. M.S.v.B.-B. was supported by the Mildred Scheel Stiftung der Deutschen Krebshilfe e.V. B.M. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. J.L.S. is a recipient of a Special Fellowship of the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. K.C.O. is a National Multiple Sclerosis Society fellow. E.C.G. is a recipient of a Burroughs Wellcome Clinical Scientist Award.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dr Toyoshima for providing us with the mouse antikinectin antibody. We also thank Drs Nagase and Kronke for providing us with full-length cDNAs encoding kinectin.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal