Comment on Palumbo et al, page 178

Palumbo and colleagues show that platelets and fibrinogen protect metastatic tumor cells from elimination by NK cells, confirming a striking mechanistic link between activation of the blood coagulation system and the spread of tumor metastases.

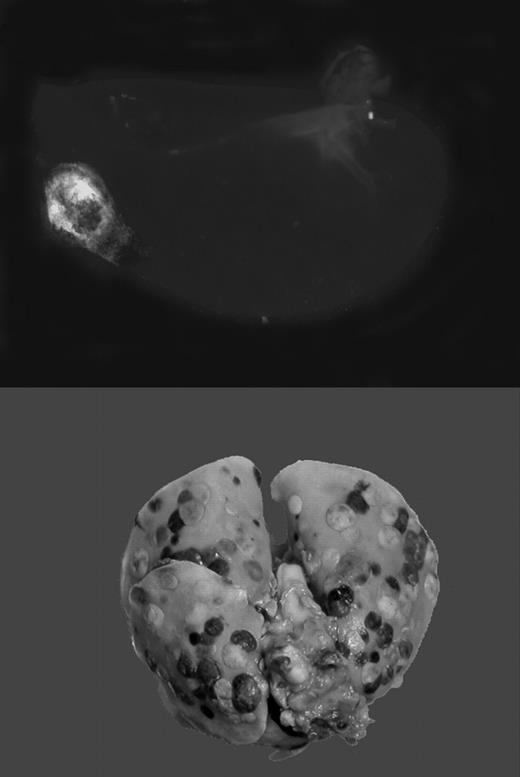

Tumor cells travel through blood or lymphatic vessels to secondary organs, where they exit the vascular compartment to form metastases. This route of tumor dissemination through the bloodstream has been termed hematogenous metastasis. The level of tumor-associated procoagulant activity correlates directly with metastatic potential, and forced expression of the initiator of blood coagulation, tissue factor (TF), is sufficient to confer metastatic potential onto tumor cells.1 In animal models, metastasis can be effectively suppressed by genetic disruption or pharmacologic inhibition of the coagulation system or platelet activity. Using genetically altered mice lacking fibrinogen, Palumbo and colleagues previously demonstrated that absence of fibrinogen markedly reduces the formation of pulmonary and lymph node metastases, without affecting growth of the primary tumor.2 Recent work by Camerer and colleagues3 confirms this finding, and, in addition, showed that platelets are also necessary for successful hematogenous metastasis. Importantly, attenuating platelet responsiveness to thrombin suppressed metastasis to a similar extent as the complete absence of platelets, or the lack of fibrinogen. Together, these studies clearly established that metastasis of circulating tumor cells requires TF-initiated coagulation on the surface of tumor cells, which promotes thrombin generation, fibrin formation, and platelet aggregation. However, it remained obscure how this chain of events translates into an enhancement of metastasis.FIG1

Gαq deficiency dramatically diminishes the metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 178.

Gαq deficiency dramatically diminishes the metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 178.

The current article by Palumbo and colleagues follows an earlier lead suggesting that platelet aggregation around procoagulant tumor cells shields these cells from attack by cytolytic natural killer (NK) cells.4 NK cells eliminate the vast majority of circulating tumor cells, and NK cell elimination or inhibition results in greatly exaggerated metastasis. NK cell–mediated tumor killing requires direct contact with the target cell, possibly via transcellular interleukin 15 presentation.5 The acquisition of a platelet cloak around the tumor cell could in theory prevent such interactions, and allow the tumor cell to escape the surveillance by cells of the innate immune system. Palumbo et al test this hypothesis by employing fibrinogen-deficient mice, mice with aggregation-defective platelets (lacking the signal transducer Gαq), and mice with defective NK cell function. They demonstrate that the metastasis-enhancing effect of fibrinogen and platelets is completely abolished in the absence of NK cells, thus providing an independent and convincing experimental verification of the hypothesis proposed by Nieswandt and colleagues.4 It remains to be shown whether platelets protect tumor cells indeed simply by providing a physical barrier, or whether platelets modulate NK function in some additional way. The current article by Palumbo et al also establishes an experimental paradigm in which NK-independent mechanisms linking tumor metastasis and hemostasis can be addressed. Insight into the role of platelets in the adhesion of tumor cells to endothelium, the effects of thrombin on mobilization of tumor cells, and the role of coagulation, platelets, and receptors in the extravasation/diapedesis of tumor cells is sure to emerge from further analysis of these pathways in NK-deficient mice.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal