Abstract

ABCG2/BCRP is a member of the adenosine triphosphate–binding cassette (ABC) transporter family and is expressed in intestine, kidney, and liver, where it modulates the absorption and excretion of xenobiotic compounds. ABCG2 is also expressed in hematopoietic stem cells and erythroid cells; however, little is known regarding its role in hematopoiesis. Abcg2 null mice have increased levels of protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) in erythroid cells, yet the mechanism for this remains uncertain. We have found that Abcg2 mRNA expression was up-regulated in differentiating erythroid cells, coinciding with increased expression of other erythroid-specific genes. This expression pattern was associated with significant amounts of ABCG2 protein on the membrane of mature peripheral blood erythrocytes. Erythroid cells engineered to express ABCG2 had significantly lower intracellular levels of PPIX, suggesting the modulation of PPIX level by ABCG2. This modulating activity was abrogated by treatment with a specific ABCG2 inhibitor, Ko143, implying that PPIX may be a direct substrate for the transporter. Taken together, our results demonstrate that ABCG2 plays a role in regulating PPIX levels during erythroid differentiation and suggest a potential role for ABCG2 as a genetic determinant in erythropoietic protoporphyria.

Introduction

ABCG2, also known as BCRP/MXR/ABCP, is a member of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)–binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. Like MDR1, a well-studied member of this family, ABCG2 is highly expressed in hepatic canalicular membranes, renal proximal tubules, and apical membranes of intestinal epithelium.1-4 Overexpression of ABCG2 in cell lines confers resistance to a variety of chemotherapeutic drugs,5-8 suggesting a role for ABCG2 expression in cancer cells as a mechanism of resistance to chemotherapy. We and others have shown expression of ABCG2 mRNA in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and Ter119-positive erythrocytes9,10 ; however, the function of ABCG2 in hematopoietic cells remains undefined.

Abcg2 null mouse models have been generated with no abnormalities in hematopoietic development observed.3,11 Abcg2 expression was required for the side population (SP) phenotype of HSCs and for protecting HSCs against mitoxantrone toxicity,9,11-13 suggesting a potential role for ABCG2 as an HSC marker and as a mechanism for protecting HSCs against naturally occurring toxins. Jonker et al found that Abcg2-/- mice had an elevated protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) level in red blood cells,3 a phenotype similar to the erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) caused by deficiency of ferrochelatase activity, but without clinical manifestations such as photosensitivity. The mechanism and significance for this accumulation of PPIX are unknown, and the expression pattern of ABCG2 during erythroid development has not been defined. In this study, we have examined expression of ABCG2 during erythroid maturation and directly studied whether ABCG2 expression can decrease PPIX levels in several cellular systems. These results suggest a direct role of ABCG2 transporter in PPIX metabolism.

Materials and methods

Mice and cell lines

Abcg2-/- mice were generated in our lab and are on 129/C57BL6 mixed genetic background.11 Murine erythroleukemic (MEL) cells and human erythroleukemic K562 cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). K562 cells overexpressing ABCG2 (K562/ABCG2) were generated by transducing the cells with the HaBCRP retroviral vector pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus-G (VSV-G) envelope and subsequent sorting after staining with anti-ABCG2 antibody 5D3 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA),14 which recognizes an extracellular epitope of ABCG2 using fluorescent-activated cell sorter. No drug selection was applied. These studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Staining of red blood cells with antibodies for flow cytometry

Peripheral blood samples were collected in heparinized tubes from healthy human donors after informed consent, from a 3-year-old rhesus macaque, and from 14-week-old Abcg2-/- mice. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN. For murine and rhesus monkey samples, 5 μL red blood cells were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed/permeabilized with cold acetone for 2 minutes on ice. Cells were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS and labeled with 10 μL anti–mouse Abcg2 antibody Bxp-53 (Monosan, The Netherlands) or 10 μL of the anti–human ABCG2 antibody Bxp-21 (Kamiya Biochemical, Seattle, WA), which cross-reacts with rhesus macaque ABCG2, for 20 minutes at room temperature. After washing, cells were incubated with 5 μL fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti–rat Ig (Camarillo, CA) or phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti–mouse Ig (DAKO, Denmark), washed, and analyzed in flow cytometry. One microliter of human red blood cells were labeled with 1 μg 5D3 for 20 minutes at room temperature, washed, and incubated with PE-conjugated anti–mouse Igs. After washing, cells were analyzed in flow cytometry.

Induction of MEL cells

Murine leukemic cell line MEL was incubated with 2% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 4 days. RNA was extracted and analyzed by Northern blot using a full-length mouse Abcg2 cDNA probe cloned from mouse kidney RNA by reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). A portion of cells were fixed/permeabilized with acetone and stained with Bxp-53 for protein expression analysis or incubated with 2.5 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 60 minutes and analyzed in a flow cytometry for Abcg2 function (LSR, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

PPIX fluorescence assay

For PPIX efflux assays, cells were incubated with 10 μM PPIX (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in DMEM/10% FBS for 30 minutes at 37°C, washed once with medium, and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Ko143 (kindly provided by Balázs Sarkadi) or 2-deoxyglucose, if used, was present during the entire procedure. Cells were spun down, resuspended into medium, and analyzed in a flow cytometry (LSR, Becton Dickinson) for PPIX fluorescence using a 695/40-nm filter after excitation by a 405 nm UV light. ATP depletion was achieved by preincubating the cells in medium containing 50 mM 2-deoxyglucose and 15 mM sodium azide for 20 minutes. Ko143 was used at 1 μM. For endogenous PPIX efflux assays, cells were treated with 1 mM δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (Sigma) for 21 hours, washed once with PBS, and directly analyzed in flow cytometry for PPIX fluorescence.

HPLC measurement of PPIX

K562 or K562/ABCG2 cells were treated with 1 mM δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (Sigma) at 5 × 105 cells/mL for 21 hours. The number of cells increased during the treatment, but no difference was seen between the 2 cell lines. Cells were washed once with PBS, and an aliquot was analyzed in flow cytometry using the same setting as for PPIX fluorescence analysis. 4 × 106 cells were pelleted and resuspended into 50 μL DMEM medium. 20 μL DMSO was added to the cells and vortexed vigorously for 5 minutes. 200 μL 60% methanol/40% 10 mM potassium phosphate monobasic solution was then added and vortexed for 5 minutes. The samples were spun down at 14 000g for 15 minutes. Twenty μL supernatant was injected into high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system to quantitate PPIX. Separation was achieved by a Shimadzu Shim-Pack CLC-ODS 4.6 mm × 150 mm column using a gradient program. Mobile phase A was 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 4.6, and solution B was methanol. Detection was with a fluorescence detector with the absorbance set at 400 nm and emission at 620 nm. This reverse-phase HPLC method is capable of separating 7 porphyrin compounds, including uroporphyrin, hexaporphyrin, heptaporphyrin, pentaporphyrin, coproporphyrin, mesoporphyrin, and protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) (data not shown). A PPIX standard curve over a concentration range of 0.1 μg/mL to 5 μg/mL was constructed for quantitation of PPIX in samples.

K562 or K562/ABCG2 cells also were treated with 1 mM δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) (Sigma) at 3 × 106 cells/mL for 7 hours. Cells were spun down, and 20 μL of supernatants were directly injected into HPLC to quantitate the PPIX in the medium. Cell pellets were washed once with PBS, and 5 × 106 cells were pelleted and processed to quantitate PPIX of the cell pellet. Separation was achieved by a Shimadzu Shim-Pack CLC-ODS 4.6 mm × 150 mm column using an isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/minute. Mobile phase was 90% methanol and 10% 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 4.6. Two standard curves were constructed for quantification of the PPIX, one for the supernatant, which was not extracted but injected directly into the HPLC system (range, 0.25-20.0 μg/mL) and another for the cell pellets, which were extracted using DMSO (range, 0.1-5.0 μg/mL).

Microarray analysis of RNA expression

Day 16 fetal liver cells were obtained from homozygous Abcg2-/- mouse embryos or wild-type mouse embryos. More than 87% of nucleated cells at this stage express the erythroid cell marker Ter119 when analyzed by flow cytometry. Friend virus–infected splenic erythroblasts were isolated as previously described15 and cultured with erythropoietin for 48 hours. RNA was extracted, labeled, and hybridized on Affymetrix Moe430A chip. The data were analyzed with MAS version 5.0 software (Affymetrix). A complete analysis of the microarray data sets will be published elsewhere.

Results

ABCG2 expression is up-regulated during erythroid differentiation

In an earlier study, we found that Abcg2 mRNA was expressed in Ter119+ erythroid cells from murine bone marrow.9 Ter119 expression identifies erythroid cells in developmental stages spanning proerythroblast to mature red blood cells.16 To more precisely study the expression pattern of Abcg2 during erythroid differentiation, we treated murine erythroleukemia (MEL) cells with DMSO for 4 days to induce erythroid differentiation. At the end of induction, more than 45% of cells were hemoglobinized when analyzed by staining with benzidine (data not shown). We then evaluated Abcg2 mRNA levels using Northern blot and protein levels using flow cytometry after staining with the anti-Abcg2 antibody Bxp-53. We found that Abcg2 mRNA was present at a relatively low level in noninduced cells and significantly increased after induction with DMSO (4.6-fold, Figure 1A). This correlated with a significant increase in Abcg2 protein expression (Figure 1B). The Abcg2 protein expressed in induced MEL cells was functional as evidenced by the ability to efflux Hoechst 33342 dye, which is a known substrate for ABCG2 (Figure 1C).

Expression of Abcg2 in MEL cells before and after induction with DMSO and in primary erythroblasts during differentiation. (A) Noninduced MEL cells and MEL cells induced with 2% DMSO for 4 days were analyzed for Abcg2 mRNA by Northern blot, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)probe served as loading control. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of MEL cells after staining with anti-Abcg2 antibody Bxp-53. (C) Hoechst 33342 fluorescence in cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Shaded area in B and C indicates noninduced MEL cells; solid line in B and C, MEL cells induced with DMSO. (D) Murine splenic proerythroblasts were cultured for differentiation; samples were taken at different time points and measured for Abcg2 mRNA using microarray. Baso indicates basophilic erythroblasts; poly, polychromatic erythroblasts; and ortho, orthochromatic erythroblasts.

Expression of Abcg2 in MEL cells before and after induction with DMSO and in primary erythroblasts during differentiation. (A) Noninduced MEL cells and MEL cells induced with 2% DMSO for 4 days were analyzed for Abcg2 mRNA by Northern blot, glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)probe served as loading control. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of MEL cells after staining with anti-Abcg2 antibody Bxp-53. (C) Hoechst 33342 fluorescence in cells analyzed by flow cytometry. Shaded area in B and C indicates noninduced MEL cells; solid line in B and C, MEL cells induced with DMSO. (D) Murine splenic proerythroblasts were cultured for differentiation; samples were taken at different time points and measured for Abcg2 mRNA using microarray. Baso indicates basophilic erythroblasts; poly, polychromatic erythroblasts; and ortho, orthochromatic erythroblasts.

We next examined the expression of Abcg2 mRNA during differentiation in primary erythroblasts. Murine erythroblasts infected with the anemia-inducing strain of Friend virus provide a model of erythroid differentiation. In the presence of erythropoietin, these cells differentiate from proerythroblasts to orthochromatic erythroblasts over 48 hours. Using microarray expression analysis, we determined that Abcg2 mRNA was present at a low level initially, consistent with its low expression in MEL cells. Starting at 4 hours of culture, Abcg2 mRNA increased and reached a peak level, representing a 10-fold increase at the polychromatic erythroblast stage, between 30 and 42 hours (Figure 1D) and then decreased at the orthochromatic erythroblast stage, when enzymes for heme synthesis, such as ALAS2 and ferrochelatase, reached their peak levels (data not shown). These experiments demonstrate that Abcg2 expression increases during erythroid maturation in 2 different murine erythroid cell systems.

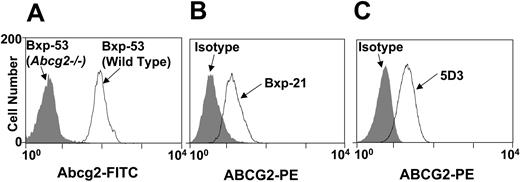

ABCG2 protein is expressed on mature red blood cells from mice, rhesus macaques, and humans

We next tested whether ABCG2 protein was present on the membrane of mature peripheral red blood cells. We collected peripheral blood from mice, rhesus macaques, and humans, and stained the cells with anti-ABCG2 monoclonal antibodies appropriate for each species. We used red blood cells from Abcg2-/- mice as negative controls for murine cells and isotype antibody-labeled cells as controls for rhesus and human samples. We found that ABCG2 was readily detected on mature red blood cells from all 3 species (Figure 2). These results indicate that expression of ABCG2 during erythroid maturation results in significant amounts of ABCG2 protein on the membrane of mature red blood cells.

Expression of ABCG2 protein on peripheral mature red blood cells. Peripheral blood from mice, rhesus macaques, and humans were collected, stained with primary antibodies recognizing respective ABCG2, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Red blood cells from Abcg2-/- mice (shaded area) or wild-type mice (solid line) stained with anti-Abcg2 antibody Bxp-53. (B) Rhesus macaque red blood cells stained with either isotype control antibody (shaded area) or anti-ABCG2 antibody Bxp-21 (solid line). (C) Human red blood cells stained with either isotype control antibody (shaded area) or anti-ABCG2 antibody 5D3 (solid line).

Expression of ABCG2 protein on peripheral mature red blood cells. Peripheral blood from mice, rhesus macaques, and humans were collected, stained with primary antibodies recognizing respective ABCG2, and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Red blood cells from Abcg2-/- mice (shaded area) or wild-type mice (solid line) stained with anti-Abcg2 antibody Bxp-53. (B) Rhesus macaque red blood cells stained with either isotype control antibody (shaded area) or anti-ABCG2 antibody Bxp-21 (solid line). (C) Human red blood cells stained with either isotype control antibody (shaded area) or anti-ABCG2 antibody 5D3 (solid line).

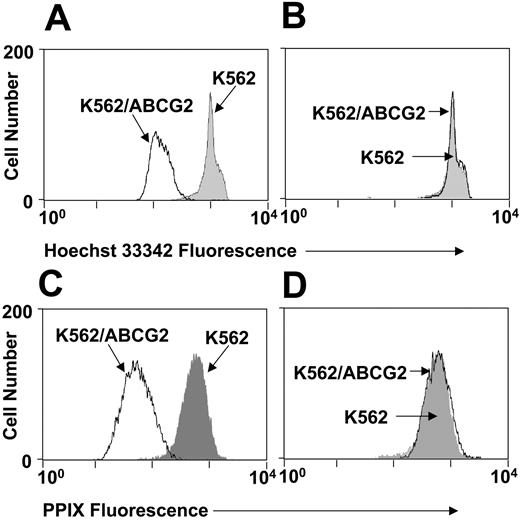

ABCG2 expression decreases exogenous PPIX accumulation in K562 cells

The accumulation of PPIX in red blood cells of Abcg2-/- mice and the marked up-regulation of ABCG2 during erythroid maturation suggests that ABCG2 may function to decrease PPIX cellular levels, perhaps through a direct efflux mechanism. To test this hypothesis, we transduced K562 cells with our HaBCRP retroviral expression vector9 and isolated a polyclonal pool of transduced cells (K562/ABCG2 cells). The expression of ABCG2 in the transduced cells was confirmed by staining with anti–ABCG2 antibody 5D314 (data not shown) and by assaying for Hoechst 33342 efflux activity (Figure 3A). This efflux activity was blocked by treatment with a specific ABCG2 functional inhibitor Ko14317 (Figure 3B).

Efflux of exogenous PPIX by ABCG2. K562 cells or K562 cells engineered to overexpress ABCG2 (K562/ABCG2) are incubated with Hoechst 33342 (A, B) or PPIX (C, D). Cells also were coincubated with the ABCG2 inhibitor Ko143 (B, D). Shaded area indicates K562 cells; solid line, K562/ABCG2 cells.

Efflux of exogenous PPIX by ABCG2. K562 cells or K562 cells engineered to overexpress ABCG2 (K562/ABCG2) are incubated with Hoechst 33342 (A, B) or PPIX (C, D). Cells also were coincubated with the ABCG2 inhibitor Ko143 (B, D). Shaded area indicates K562 cells; solid line, K562/ABCG2 cells.

We then incubated the cells with PPIX and measured fluorescence of PPIX by flow cytometry after excitation with a 405-nm UV light. The ABCG2 overexpressing cells (K562/ABCG2) had significantly lower PPIX fluorescence than parental K562 cells, consistent with PPIX efflux activity conferred by ABCG2 (Figure 3C). This activity was abrogated by treatment with Ko143 (Figure 3D). These results show that PPIX levels are decreased by expression of ABCG2.

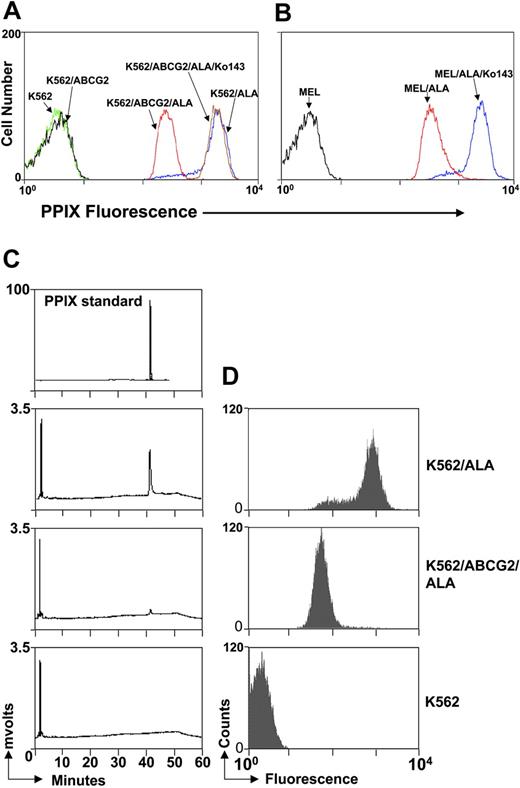

ABCG2 decreases the levels of endogenously produced PPIX in erythroid cells

Although ABCG2 can reduce the accumulation of exogenous PPIX, it is unknown whether endogenous PPIX can be effluxed by ABCG2. PPIX is synthesized by protoporphyrinogen oxidase, which is localized in the inner mitochondrial membrane with its active side oriented toward the intermembrane space.18 To determine whether endogenously synthesized PPIX could be effluxed by ABCG2, we treated K562 cells with δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA),19,20 the second intermediate in the heme biosynthetic pathway, for 21 hours to increase the endogenous PPIX level. After this treatment, there was a 3-log increase of porphyrin fluorescence by flow cytometry (Figure 4A), indicating substantial induction of endogenous porphyrin synthesis. ALA treatment also increased the fluorescence in K562/ABCG2 cells, but to a significantly lesser extent than in parental K562 cells (Figure 4A). This activity on porphyrin fluorescence was specific for ABCG2, because when Ko143 was added, the porphyrin fluorescence of K562/ABCG2 cells became indistinguishable from that of parental K562 cells (Figure 4A). These results show that endogenous porphyrin levels also can be decreased by ABCG2 expression.

Efflux of endogenous PPIX by ABCG2. (A) K562 cells or K562/ABCG2 cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 21 hours to induce endogenous PPIX, with or without 1 μM Ko143, and analyzed for PPIX fluorescence. Blue line indicates K562 + ALA; red line, K562/ABCG2 + ALA; brown line, K562/ABCG2 + ALA + Ko143; green line, nontreated K562 cells; black line, nontreated K562/ABCG2 cells. (B) MEL cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 21 hours with or without 1 μM Ko143 and analyzed in flow cytometry for PPIX fluorescence. Red line indicates MEL + ALA; blue line, MEL + ALA + Ko143; black line, nontreated MEL cells. (C) K562 or K562/ABCG2 cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 21 hours and pelleted. The amount of PPIX in pelleted cells was measured in an HPLC assay. (D) An aliquot of cells also was analyzed in a flow cytometry for fluorescence. PPIX was undetectable in nontreated K562 cells as shown in the bottom panels.

Efflux of endogenous PPIX by ABCG2. (A) K562 cells or K562/ABCG2 cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 21 hours to induce endogenous PPIX, with or without 1 μM Ko143, and analyzed for PPIX fluorescence. Blue line indicates K562 + ALA; red line, K562/ABCG2 + ALA; brown line, K562/ABCG2 + ALA + Ko143; green line, nontreated K562 cells; black line, nontreated K562/ABCG2 cells. (B) MEL cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 21 hours with or without 1 μM Ko143 and analyzed in flow cytometry for PPIX fluorescence. Red line indicates MEL + ALA; blue line, MEL + ALA + Ko143; black line, nontreated MEL cells. (C) K562 or K562/ABCG2 cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 21 hours and pelleted. The amount of PPIX in pelleted cells was measured in an HPLC assay. (D) An aliquot of cells also was analyzed in a flow cytometry for fluorescence. PPIX was undetectable in nontreated K562 cells as shown in the bottom panels.

Similar experiments were conducted using MEL cells, which express low level of Abcg2 even in the uninduced state (Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 4B, uninduced MEL cells treated with ALA showed an increase in PPIX fluorescence, consistent with an induction in endogenous PPIX synthesis with ALA. Treatment of ALA-induced MEL cells with Ko143 increased PPIX fluorescence even further, compared with cells that were treated with ALA alone. This shows that inhibition of endogenously expressed ABCG2 leads to accumulation of endogenously produced PPIX in erythroid cells.

To confirm that the fluorescence in ALA-treated cells comes from PPIX, but not from other porphyrins of heme pathway, we directly measured PPIX level in these cells 21 hours after ALA treatment by HPLC. We found that PPIX was the only porphyrin detectable after ALA treatment. The amount of PPIX was 308.9 ± 20.6 ng per 1 × 106 K562 cells (n = 3) and 28.7 ± 1.8 ng per 1 × 106 K562/ABCG2 cells, a 10.8-fold difference, which parallels the difference of fluorescence intensity measured by flow cytometry in these cells (759.9 ± 8.9 vs 55.7 ± 1.7), a 13.7-fold difference, n = 3. A representative HPLC assay is shown in Figure 4C and flow cytometry assay in Figure 4D. This result demonstrates that endogenous PPIX can be decreased by ABCG2 expression and that fluorescence detection was a reliable measurement for relative PPIX level in these cells.

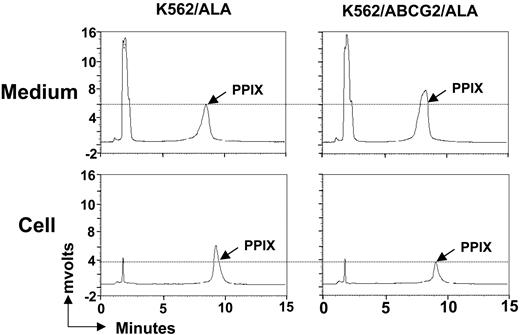

To confirm that ABCG2 can efflux PPIX into medium, we directly measured PPIX levels in both the medium and within cells after 7 hours of ALA treatment by a sensitive and specific chromatographic method (Figure 5). We found that the amount of PPIX in the medium from K562/ABCG2 cell cultures was significantly higher compared to that of K562 cells (2220 ± 160 ng vs 1420 ± 230 ng per 1 × 106 cells, n = 3, P < .001). In contrast, the amount of PPIX in the cell pellet from K562/ABCG2 cells was significantly lower than that of K562 cells (54 ± 6 ng vs 107 ± 7 ng per 1 × 106 cells, n = 3, P < .01). This result demonstrates that endogenous PPIX can be directly effluxed by ABCG2.

ABCG2 effluxes endogenous PPIX into medium. K562 or K562/ABCG2 cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 7 hours, and the PPIX levels in both medium and within cells were measured by HPLC. The peak of PPIX is indicated in each panel. The peak on the left represents a component in the culture medium (not produced by cells) and serves as an internal control.

ABCG2 effluxes endogenous PPIX into medium. K562 or K562/ABCG2 cells were incubated with 1 mM ALA for 7 hours, and the PPIX levels in both medium and within cells were measured by HPLC. The peak of PPIX is indicated in each panel. The peak on the left represents a component in the culture medium (not produced by cells) and serves as an internal control.

Mature red blood cells can efflux PPIX based on plasma membrane expression of ABCG2

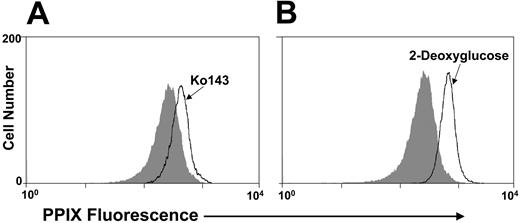

In order to determine if endogenously expressed ABCG2 in mature peripheral red blood cells could decrease intracellular PPIX levels, we incubated murine peripheral red blood cells with PPIX, with or without the Abcg2 inhibitor Ko143. The PPIX fluorescence was significantly higher in the presence of Ko143 (Figure 6A), showing that the ABCG2 function on the plasma membrane was decreasing PPIX levels in primary, mature erythroid cells. This result was confirmed with another experiment in which cells were treated with 2-deoxyglucose to inhibit the synthesis of ATP, which is required for all ABC transporter functions. As shown in Figure 6B, PPIX fluorescence was significantly increased in murine red blood cells treated with 2-deoxyglucose. These experiments confirm that the ABCG2 protein functions in mature red blood cells to decrease intracellular PPIX levels.

Red blood cells efflux PPIX due to expression of ABCG2. (A) Murine peripheral red blood cells were incubated with PPIX, with Ko143 (solid line) or without Ko143 (shaded area) and analyzed for PPIX fluorescence. (B) Murine peripheral red blood cells were incubated with (solid line) or without (shaded area) 2-deoxyglucose and sodium azide and analyzed for PPIX fluorescence.

Red blood cells efflux PPIX due to expression of ABCG2. (A) Murine peripheral red blood cells were incubated with PPIX, with Ko143 (solid line) or without Ko143 (shaded area) and analyzed for PPIX fluorescence. (B) Murine peripheral red blood cells were incubated with (solid line) or without (shaded area) 2-deoxyglucose and sodium azide and analyzed for PPIX fluorescence.

Expression of enzymes in heme biosynthesis pathway in erythroid cells from Abcg2-/- mice

One mechanism by which loss of ABCG2 could lead to increased levels of PPIX would be a secondary alteration in the level of enzymes involved in the heme biosynthesis pathway, especially the rate-limiting enzymes ALA synthase and ferrochelatase. To rule out this possibility, we used microarray analysis to examine expression of these enzymes in erythroid cells from Abcg2-/- mice. We extracted RNA from day 16 fetal liver cells, which are primarily nucleated erythroid cells, and performed microarray analysis on Affymetrix MOE430A chips. Among the 22 626 transcripts represented on the chip, 44% and 41% are expressed from Abcg2-/- and wild-type samples, respectively. Among the transcripts that are expressed in either genotype, 56 showed increased expression (2.1- to 8-fold), and 26 showed decreased expression (2.1- to 10.6-fold) in Abcg2-/- samples.

Among the 8 enzymes directly involved in heme biosynthesis, 7 showed no significant difference between the 2 genotypes. There was a 1.6-fold increase of 1 of the 2 transcripts representing coproporphyrinogen oxidase in Abcg2-/- sample (Table 1), which catalyzes the conversion of coproporphyrinogen to protoporyphyrinogen IX. However, we recognize that the microarray assay measures only relative changes in mRNA levels and cannot rule out differences in protein levels of these enzymes. This is relevant because several of these enzymes may be regulated posttranscriptionally.

Microarray analysis of enzymes involved in heme synthesis

. | Average signal intensity . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heme synthesis enzymes . | Wild-type . | Abcg2 -/- . | P . | |

| ALA synthase 1 | 799 | 675 | .02 | |

| ALA synthase 2 | 38 528 | 33 733 | .16 | |

| Aminolevulinate dehydratase | 7 880 | 6 602 | .38 | |

| Porphobilinogen deaminase | 17 175 | 15 458 | .5 | |

| Uroporphyrinogen III synthase | 4 078 | 4 416 | .37 | |

| Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | 8 216 | 6 404 | .03 | |

| Coproporphyrinogen oxidase | 6 045 | 9 388 | .00002* | |

| Protoporphyrinogen oxidase | 5 138 | 5 062 | .13 | |

| Ferrochelatase | 7 277 | 7 111 | .5 | |

. | Average signal intensity . | . | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heme synthesis enzymes . | Wild-type . | Abcg2 -/- . | P . | |

| ALA synthase 1 | 799 | 675 | .02 | |

| ALA synthase 2 | 38 528 | 33 733 | .16 | |

| Aminolevulinate dehydratase | 7 880 | 6 602 | .38 | |

| Porphobilinogen deaminase | 17 175 | 15 458 | .5 | |

| Uroporphyrinogen III synthase | 4 078 | 4 416 | .37 | |

| Uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | 8 216 | 6 404 | .03 | |

| Coproporphyrinogen oxidase | 6 045 | 9 388 | .00002* | |

| Protoporphyrinogen oxidase | 5 138 | 5 062 | .13 | |

| Ferrochelatase | 7 277 | 7 111 | .5 | |

Difference considered significant

We also compared the expression of ABC transporter members in erythroid cells from wild-type and Abcg2-/- fetal liver cells. Of 51 murine ABC transporters, 37 are represented on MOE430A chip, among them, 19 are expressed in wild-type cells. Abcg2, Abcb10, Abca1, Abcb4, Abcb6, Abce1, Abcc5, Abcb7, and Abcg1 are expressed at relatively high levels, with signal intensities higher than 1000. ABCG2 and ABCB10 are the 2 most highly expressed transporters, ranked as top 6% and 7% of all the transcripts that are expressed in erythroid cells, with signal intensities of 5295 and 4676, respectively. Abcb10 is a mitochondrial transporter that has been shown to be highly expressed in maturing erythroid cells.21 Except for Abcg2, which was knocked out in Abcg2-/- mice, no alteration of expression of any other ABC transporters was noted when comparing wild-type and Abcg2-/- mice.

Discussion

Considering the established role of ABC transporters in human disease,22,23 it is important to ascertain the normal physiologic role of the ABCG2 transporter. Several observations suggest an important function for ABCG2 in hematopoiesis. Abcg2 mRNA is expressed in primitive HSCs and is then down-regulated during myeloid differentiation.9 However, there are no detectable hematopoietic abnormalities in Abcg2 null mice except for an increased level of PPIX in erythrocytes.3,11 Therefore, we sought to better understand the expression pattern of Abcg2 during erythropoiesis and the mechanism by which loss of Abcg2 leads to PPIX accumulation.

In this study, we found that Abcg2 expression was sharply up-regulated during erythroid differentiation and was present on the plasma membrane of mature red blood cells. In fact, Abcg2 was one of the most highly induced genes in Friend virus–infected primary erythroblasts. The induction of Abcg2 mRNA in polychromatic erythroid precursors parallels the active biosynthesis of heme and hemoglobin. These findings are consistent with an important function in erythroid cells, most likely being modulation of products in the heme biosynthetic pathway.

The mechanism by which ABCG2 deletion leads to PPIX accumulation has not been clear; however, the most straightforward explanation is that PPIX could be a direct substrate for the transporter. We now show that K562 cells that have been engineered to express high levels of ABCG2 have significant reduction in PPIX levels after incubation with PPIX in the medium. This effect was directly blocked by Ko143, an ABCG2 transporter inhibitor. Similar reduction also was seen when either K562 or MEL cells were induced with ALA to synthesize endogenous PPIX. Direct measurement of PPIX by HPLC showed that the PPIX level was significantly higher in the medium, but lower within the cells of K562/ABCG2 cell culture, compared to that of K562 cells. Moreover, an increase in intracellular PPIX was seen in primary mature red blood cells that were incubated with exogenous PPIX and ABCG2 inhibitors. These results demonstrate that PPIX is a direct substrate for the ABCG2 transporter.

An alternate possibility would be that loss of ABCG2 was resulting in secondary alterations in the levels of enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway. The expression of mRNAs for the majority of these enzymes in fetal liver erythroblasts, including the rate-limiting enzymes ALA synthase and ferrochelatase, showed no secondary alterations. We did find a modest increase in coproporphyrinogen oxidase mRNA associated with loss of Abcg2. While we cannot exclude the possibility that this could increase PPIX levels, it seems unlikely that this alone would cause the 10-fold increase of PPIX seen in red blood cells of Abcg2-/- mice. Moreover, the hematocrit and hemoglobin levels are comparable between wild-type and Abcg2-/- mice,13 suggesting normal activity of heme synthesis enzymes. Another possibility would be that ABCG2 could modulate a factor that causes a secondary accumulation of endogenous PPIX. This putative factor could degrade PPIX or inhibit ferrochelatase; however, no such factors have been identified.

Accumulation of PPIX in mature red blood cells that were incubated with ABCG2 inhibitors suggests that Abcg2 acts at the level of the plasma membrane to increase PPIX extrusion. PPIX is lipid soluble and can diffuse through the plasma membrane; however, our data suggest that active transport mediated by ABCG2 can further decrease intracellular PPIX levels. This mechanism may be necessary to prevent cellular toxicity under pathological conditions in which PPIX accumulates. Increases in PPIX in erythrocytes is characteristic of the human disease of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP), which is characterized by mild to moderate photosensitivity and in some cases, hepatic manifestations but no hematologic manifestations. Most of these cases have been associated with autosomal dominant mutations in the ferrochelatase gene, which catalyzes the insertion of iron into PPIX. While the EPP-like phenotype in Abcg2-/- mice lacks the photosensitivity seen in EPP mouse models or the clinical manifestations seen in humans with ferrochelatase deficiency,24-26 it is possible that ABCG2 modulates the phenotype of ferrochelatase deficiency. It is important to note that the inheritance pattern of EPP due to ferrochelatase mutations shows highly variable degrees of penetrance27 and that a few cases of EPP with recessive inheritance have been noted.28 Human polymorphisms of the ABCG2 gene recently have been described,29 and it is possible that these may represent mutations affecting PPIX levels in the face of ferrochelatase deficiency or in autosomal recessive cases. Another possible role for ABCG2 would be the control of PPIX levels during exposure to environmental toxins such as lead toxicity, which leads to marked elevation in cellular protoporphyrin levels. Both of the possibilities can now be tested with available mouse models.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 16, 2004 DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1566.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL67366 (B.P.S.) and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank the flow cytometry lab and Hartwell Center for sample analysis, Geoffrey Neale for assistance in analysis of microarray data, and Taihe Lu for help with the Northern blot analysis.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal