We report here on the long-term follow-up on 162 patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (SCT) at a single center from 1989 to 1999. Twenty-five patients with human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched sibling donors underwent T-cell-depleted allogeneic SCT, and 137 patients without HLA-matched sibling donors underwent autologous SCT. The 100-day mortality was 4% for both groups, but later morbidity and mortality were negatively affected on outcome. Progression-free survival was significantly longer following autologous than allogeneic SCT, but there was no difference in overall survival and no difference in the cumulative incidence of disease recurrence or deaths without recurrence between the 2 groups. At a median follow-up of 6.5 years there is no evidence of a plateau of progression-free survival. The majority of patients treated with donor lymphocyte infusions after relapse responded, demonstrating a significant graft-versus-leukemia effect in CLL. From these findings we have altered our approach for patients with high-risk CLL and are currently exploring the role of related and unrelated allogeneic SCT following reduced-intensity conditioning regimens.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is characterized by the presence in the peripheral blood of a clonal population of small B lymphocytes expressing the characteristic morphology and immunophenotype with cells expressing CD19, CD5, and CD23. Although fludarabine has emerged as the treatment of choice in this disease, there is no evidence to date that conventional therapy is curative.1 Despite the high initial response rates reported with conventional chemotherapy, patients invariably relapse and subsequently develop resistance to chemotherapy.

Stem cell transplantation (SCT) has become the treatment of choice for an increasing number of selected patients with hematologic malignancies. However, relatively fewer patients with CLL have been treated with this approach. CLL is largely a disease of the elderly with a median age at presentation of older than 65 years, the majority of whom would not tolerate the toxicity associated with high-dose myeloablative treatment approaches. The disease has a very long natural history, so there is reluctance to subject patients to a treatment approach with a significant morbidity and potential mortality, and by the time of referral to transplantation centers, many of these patients have been very heavily pretreated, with development of chemoresistant disease and decreased stem cell reserve. The majority of patients do not have a suitable allogeneic donor, and the use of autologous bone marrow (BM) or peripheral blood stem cells has been hampered by the extensive leukemic infiltration of the bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement that is invariable with this disease.

There are, nonetheless, reasons why investigators have examined the role of myeloablative treatment regimens in the management of CLL.2-8 Up to 40% of patients with CLL are younger than age 60 and 12% are younger than age 50 years at presentation, and these younger patients almost invariably die of their disease or its complications.9 The disease is characterized by chemosensitivity at least earlier in the disease course, providing a rationale for attempting to overcome subsequent drug resistance by the use of chemotherapy dose escalation. Although many patients with this often indolent disease are clearly not suitable candidates for approaches such as SCT, it is possible to identify patients with CLL who have sufficiently poor prognosis to merit more experimental treatment approaches with curative intent.

A clinical trial was initiated at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 1989 to establish the feasibility of performing high-dose therapy with hematopoietic SCT in CLL, and the early results of the pilot study in previously relapsed patients were reported previously.2 We now report the outcome and long-term follow-up of 162 patients with high-risk CLL who underwent autologous (n = 137) or T-cell-depleted (TCD) allogeneic SCT from an HLA-matched sibling donor (n = 25). The 100-day mortality was 4% in both autologous and allogeneic SCT groups, although later treatment-related mortalities had a major effect on outcome. With a median follow-up of 6.5 years there was no difference in overall survival, and the 6-year overall survival was 58% after autologous SCT and 55% after allogeneic SCT. Progression-free survival was significantly longer following autologous SCT than after TCD allogeneic SCT, but no significant differences were observed in disease recurrence or deaths without recurrence according to type of transplantation.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients

From 1989 to 1994, eligible patients were patients with poor prognosis CLL who had relapsed after prior therapy (protocol 89-064). From 1994, patients with poor prognosis disease were also eligible for this approach in first complete or partial remission (protocol 94-055). The rationale for this change was that by 1994 many patients had received purine analog therapy before consideration for transplantation, and it was becoming increasingly difficult for such patients to achieve a protocol-eligible minimal disease state in response to salvage therapy. The studies are combined for reporting here because 94-055 was a continuation of 89-064. There was no requirement for specific induction or salvage therapy prior to SCT on either protocol.

Patients with HLA-matched siblings underwent an allogeneic SCT, whereas all other patients underwent autologous SCT. The preparative regimen for both autologous and allogeneic patients was cyclophosphamide 60 mg/kg/d for 2 sequential days, followed by total body irradiation (TBI) administered at low-dose rate of 10 cGy per minute in 7 fractionated doses of 200 cGy twice daily over 4 consecutive days to a total of 14 Gy total body irradiation. Within 18 hours of completion of radiotherapy, patients received either autologous BM that had been cryopreserved after purging with a cocktail of anti-B-cell monoclonal antibodies (anti-C20, anti-CD10, and B5) and complement2,10 or BM harvested from an HLA-identical sibling donor that had been treated in vitro with anti-CD6 monoclonal antibody and complement as previously described.2,11 Approval was obtained from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board for these studies. Informed consent was provided from each patient according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Immunoglobulin sequencing and assessment of minimal residual disease

To identify patient leukemia-related immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangements, diagnostic samples were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplified using a series of 6 VH leader or 7 VH family FR1 consensus primers and a JH consensus primer.12 Purified PCR fragments were sequenced on both strands, and VH, DH, and JH segments were identified with a closest matching known human germ line gene using the ImMuno-Gene Tics (IMGT) Database (http://imgt.cines.fr; IMGT; European Bioinformatics Institute, Montepellier, France), the IGBLast search (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/igblast/; National Cancer for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD), or V BASE directory using DNAPLOT (http://vbase.mrc-cpe.cam.ac.uk; Center for Protein Engineering, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Quantitative real-time analysis of IgH rearrangements were performed as previously described.13

Statistical considerations

Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the length of time from the date of SCT to any recurrent or progressive disease or death, whichever occurred first. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the length of time from the date of SCT to death from any cause. PFS and OS percentages, standard errors, and treatment effect comparisons were obtained from the Kaplan-Meier method,14 Greenwood formula,15 and log-rank test,16 respectively. Cumulative incidence of relapse is reported with death in remission as the competing risk.17 Cumulative incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) for the patients who underwent autologous transplantation is reported with death as the competing risk.17 Patients were evaluated in groups classified as having received an autologous transplant or an allogeneic transplant, but it should be stressed that any such comparison of patients who received an autologous transplant with patients who received an allogeneic transplant is not a randomized comparison. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test18 was used for testing differences between continuous variables, and associations between categorical variables were assessed by a Fisher exact test.19 All probability values were obtained from 2-sided tests. The results are reported at a median follow-up of 6.5 years.

Results

Patient characteristics

To be eligible for this approach, patients up to 66 years had to have poor prognosis CLL, defined as patients with progressive symptomatic disease requiring therapy (as defined by National Cancer Institute Working Group guidelines20 ) who had Rai stage III or IV disease (Binet stage C) or patients with Rai stage II (Binet stage B) with poor prognosis factors, including rapid doubling time (< 12 months),21,22 diffuse bone marrow involvement,23 or adverse cytogenetics.24,25 This protocol had completed accrual before fluorescent in situ hybridization techniques became widely adopted to define prognosis in CLL.26 Patients had to achieve a protocol-eligible minimal disease state defined as no nodal masses larger than 2 cm, and bone marrow infiltration less than 30% after therapy. Twenty-seven patients with persistent splenomegaly larger than 15 cm on computerized tomography scanning who had otherwise achieved protocol eligibility underwent splenectomy before transplantation. There were no specific requirements for previous therapy, and patients were eligible for enrollment once they had achieved the protocol-eligible minimal disease state. One hundred sixty-seven patients were registered on the 2 consecutive protocols. From 1989 to 1994, 46 patients who had relapsed after first-line therapy and responded to salvage therapy were enrolled to protocol 89-064. From 1994 patients were also eligible once they completed induction therapy, and 121 patients were enrolled from 1995 to 1999 to protocol 94-055. Three patients were registered but did not undergo SCT because of disease progression, and 2 patients withdrew consent. Reported here are the outcomes of 162 consecutive patients with high-risk CLL who underwent SCT. The characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1.

Patient characteristics according to transplantation

. | Autologous transplantation . | Allogeneic transplantation . | All patients . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases, no. | 137 | 25 | 162 |

| Protocol, no. | |||

| 89-064 | 32 | 12 | 44 |

| 94-055 | 105 | 13 | 118 |

| Median age, y (range) | 51 (19-66) | 47 (28-55) | 49 (19-66) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 101 (74) | 20 (80) | 121 (75) |

| Female | 36 (26) | 5 (20) | 41 (25) |

| Median time from diagnosis to transplantation, mo (range) | 46 (7-212) | 45 (11-145) | 46 (7-212) |

| Prior therapy, no. (%) | |||

| Alkylator only | 8 (6) | 2 (8) | 10 (6) |

| Fludarabine only | 29 (22) | 8 (32) | 37 (23) |

| Sequential alkylator and fludarabine | 59 (43) | 11 (44) | 70 (43) |

| Concomitant alkylator and fludarabine with or without rituximab | 41 (30) | 4 (16) | 45 (27) |

| IgH mutational status, no. (%) | |||

| Mutated, at least 2 | 11 (8) | 4 (16) | 15 (9) |

| Unmutated, less than 2% | 124 (90) | 21 (80) | 145 (90) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

. | Autologous transplantation . | Allogeneic transplantation . | All patients . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total cases, no. | 137 | 25 | 162 |

| Protocol, no. | |||

| 89-064 | 32 | 12 | 44 |

| 94-055 | 105 | 13 | 118 |

| Median age, y (range) | 51 (19-66) | 47 (28-55) | 49 (19-66) |

| Sex, no. (%) | |||

| Male | 101 (74) | 20 (80) | 121 (75) |

| Female | 36 (26) | 5 (20) | 41 (25) |

| Median time from diagnosis to transplantation, mo (range) | 46 (7-212) | 45 (11-145) | 46 (7-212) |

| Prior therapy, no. (%) | |||

| Alkylator only | 8 (6) | 2 (8) | 10 (6) |

| Fludarabine only | 29 (22) | 8 (32) | 37 (23) |

| Sequential alkylator and fludarabine | 59 (43) | 11 (44) | 70 (43) |

| Concomitant alkylator and fludarabine with or without rituximab | 41 (30) | 4 (16) | 45 (27) |

| IgH mutational status, no. (%) | |||

| Mutated, at least 2 | 11 (8) | 4 (16) | 15 (9) |

| Unmutated, less than 2% | 124 (90) | 21 (80) | 145 (90) |

| Unknown | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

One hundred thirty-seven patients without an HLA-matched sibling donor underwent B-cell-purged autologous SCT, and 25 patients with an HLA-matched sibling donor underwent TCD allogeneic SCT. The median age for all patients was 49 years (range, 19-66 years), 97% were white, and 75% were men, in keeping with the male preponderance and the poorer prognosis status of male patients with CLL.27 The median time from diagnosis to transplantation was 46 months for autologous SCT and 45 months for allogeneic SCT. There were no requirements for prior therapy, and 10 patients (6%) received only alkylator agents, 37 patients (20%) received only fludarabine therapy, and all others received both alkylator and fludarabine therapy either sequentially (70 patients) or concomitantly (45 patients). Although at the time these protocols were written the prognostic significance of the IgH mutational status was not appreciated,28,29 sequencing of IgH from diagnostic tissue in these patients using previously described techniques12 demonstrated that the IgH was unmutated in 145 cases (90%) and mutated (> 2% mutated from germ line) in only 15 cases (9%), in keeping with these being patients with poor prognosis. The IgH could not be sequenced from 2 patients.

Effect of prior therapy on engraftment

All patients who underwent allogeneic SCT engrafted with a median time to neutrophil engraftment (neutrophil count > 0.5 × 109/L for 2 sequential days) of 13 days (range, 8-25 days). Previous therapy given had no effect on time to engraftment in the patients who underwent allogeneic SCT, but it did have an effect on time to engraftment among the patients who underwent autologous SCT. Among the 137 patients who underwent autologous SCT, 8 patients received prior alkylator therapy only, 29 patients received fludarabine only, and 59 patients received sequential alkylator agent and fludarabine. The median time to neutrophil engraftment for these patients was 17 days (range, 9-744 days), with one patient who received cyclophosphamide and fludarabine sequentially having very delayed engraftment. An additional 41 patients (30%) were treated to protocol eligibility with combination fludarabine and cyclophosphamide with or without rituximab (FC/R), and one patient relapsed after prior fludarabine in combination with chlorambucil and then received fludarabine alone as salvage therapy. Three of these patients failed to engraft, 2 having received fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) and one having previously received combination of fludarabine and chlorambucil. For the patients who underwent autologous SCT treated with concomitant FC/R, the median time to neutrophil engraftment was 19 days (range, 12-57 days) and was significantly delayed compared with those patients who did not receive this combination (P = .04).

Overall survival after stem cell transplantation

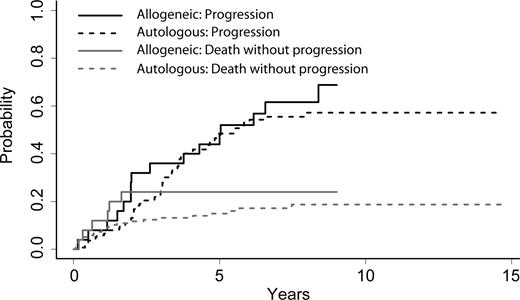

OS was similar after autologous and allogeneic SCTs (Figure 1), with 6-year OS of 58% (± 5%) after autologous SCT compared with 55% (± 10%) after allogeneic SCT (P = .96) with hazard ratio comparing autologous and allogeneic SCTs of 0.98 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53-1.83). There have been 75 (46%) deaths after SCT, 63 (46%) after autologous SCT, and 12 (48%) after allogeneic SCT, whereas 46 patients died with recurrence, 40 (29%) after autologous SCT, and 6 (24%) after allogeneic SCT. No significant differences were observed in the cumulative incidence of disease recurrence and deaths without recurrence according to type of transplantation (Figure 2).

Overall survival after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations.

Deaths without recurrence after stem cell transplantation

Of the 162 patients with CLL, 6 (4%) died within 100 days after transplantation. Five of these patients (4%) underwent autologous SCT. One patient who failed to engraft died of fungal infection, and all others died of interstitial pneumonitis. In addition, a further 18 patients who underwent autologous SCT died without evidence of disease progression after 100 days, all but one of which (death in a road traffic accident) could potentially be related to the procedure, so the overall treatment-related mortality in the patients undergoing autologous SCT could be as high as 17%. One patient (4%) who underwent allogeneic SCT died within 100 days of a rapidly progressive high-grade lymphoma. This lymphoma was negative for expression of Epstein-Barr virus and was not related to her underlying CLL by comparison of the sequence of the IgH rearrangement of the CLL cells compared with her lymphoma cells. Five additional patients also died after day 100 in the patients undergoing allogeneic SCT, all procedure related, so that the overall treatment-related mortality after T-cell-depleted allogeneic SCT was 24%. The causes of death without evidence of disease progression in all patients are shown in Table 2.

Causes of nonrelapse death after stem cell transplantation

Type of transplantation and patient UPN . | Protocol . | Cause of death . |

|---|---|---|

| Autologous | ||

| 1357 | 89-064 | Suicide |

| 1430* | 89-064 | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| 1688 | 89-064 | Multiple organ failure; fungal infection |

| 1701 | 89-064 | Not transplantation related |

| 1744 | 89-064 | Multiple organ failure |

| 1810 | 89-064 | MDS |

| 1970* | 94-055 | Respiratory failure |

| 1977 | 94-055 | MDS, GVHD, ARDS |

| 2072 | 94-055 | Unknown, confirmed no relapse |

| 2078 | 94-055 | Unknown, confirmed no relapse |

| 2447 | 94-055 | Multiorgan failure |

| 2528* | 94-055 | Respiratory failure; multiorgan failure; fungal infection |

| 2638 | 94-055 | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| 2652 | 94-055 | Respiratory failure |

| 2780 | 94-055 | Cardiac |

| 2997* | 94-055 | Respiratory failure; multiorgan failure |

| 3082 | 94-055 | Second malignancy; small cell carcinoma |

| 3166* | 94-055 | Fungal infection |

| 3205 | 94-055 | MDS, respiratory failure; infection |

| 3324 | 94-055 | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| 3433 | 94-055 | Fungal infection |

| 3448 | 94-055 | VOD |

| 3640 | 94-055 | Suicide |

| Allogeneic | ||

| 1401 | 89-064 | Infection |

| 1699 | 89-064 | Infection |

| 1734 | 89-064 | GVHD, infection |

| 1760 | 89-064 | GVHD, fungal infection; multiorgan failure |

| 2021* | 94-055 | Second malignancy, B-cell NHL |

| 3203 | 94-055 | GVHD |

Type of transplantation and patient UPN . | Protocol . | Cause of death . |

|---|---|---|

| Autologous | ||

| 1357 | 89-064 | Suicide |

| 1430* | 89-064 | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| 1688 | 89-064 | Multiple organ failure; fungal infection |

| 1701 | 89-064 | Not transplantation related |

| 1744 | 89-064 | Multiple organ failure |

| 1810 | 89-064 | MDS |

| 1970* | 94-055 | Respiratory failure |

| 1977 | 94-055 | MDS, GVHD, ARDS |

| 2072 | 94-055 | Unknown, confirmed no relapse |

| 2078 | 94-055 | Unknown, confirmed no relapse |

| 2447 | 94-055 | Multiorgan failure |

| 2528* | 94-055 | Respiratory failure; multiorgan failure; fungal infection |

| 2638 | 94-055 | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| 2652 | 94-055 | Respiratory failure |

| 2780 | 94-055 | Cardiac |

| 2997* | 94-055 | Respiratory failure; multiorgan failure |

| 3082 | 94-055 | Second malignancy; small cell carcinoma |

| 3166* | 94-055 | Fungal infection |

| 3205 | 94-055 | MDS, respiratory failure; infection |

| 3324 | 94-055 | Interstitial pneumonitis |

| 3433 | 94-055 | Fungal infection |

| 3448 | 94-055 | VOD |

| 3640 | 94-055 | Suicide |

| Allogeneic | ||

| 1401 | 89-064 | Infection |

| 1699 | 89-064 | Infection |

| 1734 | 89-064 | GVHD, infection |

| 1760 | 89-064 | GVHD, fungal infection; multiorgan failure |

| 2021* | 94-055 | Second malignancy, B-cell NHL |

| 3203 | 94-055 | GVHD |

UPN indicates unique patient number; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; VOD, venoocclusive disease; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Death within 100 days of transplantation

Disease progression after stem cell transplantation

The response criteria for complete remission in CLL include a return of hemoglobin to greater than 11 g/L and platelet count greater than 100 × 109/L, but allow for up to 30% remaining lymphocytes in the BM.30 These are not ideal criteria to apply to patients undergoing SCT in whom we are more interested in whether there are residual detectable CLL cells. Therefore, response criteria for this protocol included absence of lymphadenopathy by clinical examination and computed tomography (CT) scan, and no evidence of CLL cells within the BM by morphology and by standard dual-color flow cytometric analysis. No assessment of minimal residual disease by PCR12 or multicolor flow cytometric analysis31 is included in this present analysis. The response rate after SCT was high, and 93% of evaluable patients were in complete response (CR) by these criteria at 6 months after SCT. Disease progression occurred in 87 (54%) patients, 70 (51%) after autologous SCT and 17 (68%) after the allogeneic SCT. Progression-free survival was significantly longer for patients who underwent autologous SCT compared with those who underwent allogeneic SCT (P = .04) as shown in Figure 3. The 6-year PFS was 30% (± 4%) for patients who underwent autologous SCT patients compared with 24% (± 9%) for the patients who underwent allogeneic SCT, with a hazard ratio comparing autologous with allogeneic SCT of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.39-0.98). Of note, 7 patients who relapsed after allogeneic SCT and who had no evidence of GVHD were treated on a separate protocol with donor lymphocyte infusions prepared as previously reported.32 Patients received a single infusion of 1 × 107 CD4+ cells/kg or 3 × 107 CD4+ cells/kg. No other immune-modulating therapy was given after donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI), and no GVHD prophylaxis was used. The development of GVHD was the most significant complication of DLI, and grade II to IV acute GVHD or extensive chronic GVHD occurred in 50% of patients. Six patients responded to DLI, and response of the disease to DLI in a representative patient is shown in Figure 4. Twelve patients with progressive disease after autologous SCT have now undergone allogeneic SCT from a matched unrelated donor at this center, and 5 other patients have undergone this procedure at other centers. The outcome after these subsequent procedures is not reported here, although follow-up after second transplantation is included in OS analysis.

Cumulative incidence of disease progression and death without disease progression after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations.

Cumulative incidence of disease progression and death without disease progression after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations.

Progression-free survival after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations.

Progression-free survival after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations.

We observed that patients who received a transplant most recently had significantly worse PFS (P = .01) than patients who received a transplant earlier (Figure 5A), although there is at present no difference in overall survival (Figure 5B) (P = .14). Whether this reflects a difference in risk status of these later patients or differences of the effect of prior therapy on outcome after transplantation is not clear at present. A previous study suggested that patients with mutated IgH rearrangements have better outcome after autologous SCT than those with unmutated IgH.33 Although in the present study greater than 90% of the patients have unmutated IgH (Table 1), suggesting that we had indeed selected patients with high-risk CLL for this approach, we observed no difference in progression-free survival (P = .18) or overall survival (P = .47) for those patients who had mutated compared with those with unmutated IgH rearrangements (Figure 6).

Assessment of disease burden after TCD allogeneic SCT and after DLI in a patient with CLL. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of the CLL-specific IgH rearrangement was performed on BM samples obtained serially from this patient at the times shown following allogeneic SCT and following DLI.

Assessment of disease burden after TCD allogeneic SCT and after DLI in a patient with CLL. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis of the CLL-specific IgH rearrangement was performed on BM samples obtained serially from this patient at the times shown following allogeneic SCT and following DLI.

Outcome after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations by time of transplantation (protocol 89-039 from 1989 to 1994; protocol 94-055 from 1995). (A) Progression-free survival. Tx indicates treatment. (B) Overall survival.

Outcome after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantations by time of transplantation (protocol 89-039 from 1989 to 1994; protocol 94-055 from 1995). (A) Progression-free survival. Tx indicates treatment. (B) Overall survival.

Second malignancies after stem cell transplantation

Second (non-CLL) malignancies have developed after SCT in 31 (19%) patients (Table 3). The median time from transplantation to the diagnosis of a hematologic second malignancy was 35 months (range, 1-138 months). Thirteen patients (9%) have developed MDS at a median of 36 months (range, 11-87 months) after autologous SCT. Eight (62%) of the 13 patients diagnosed with MDS developed MDS during remission, whereas 5 patients developed MDS after progression of their CLL. The cumulative incidence of MDS with death as the competing risk for the 137 patients who received an autologous transplant is shown in Figure 7. At 8 years after transplantation the incidence of MDS was 12% (95% CI, 5%-19%). Four patients (10%) treated with FC/R developed MDS and 9 patients (9%) treated with other regimens developed MDS, and the risk of MDS was not associated with the type of prior therapy (P = .99). One patient developed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma at 13 months and another T-cell lymphoma at 138 months after autologous SCT. The B-cell lymphoma was not related to the underlying CLL clone, as assessed by IgH gene rearrangement sequencing from both malignancies. One patient developed a rapidly progressive B-cell lymphoma at one month after allogeneic SCT that was also unrelated to her underlying CLL. Fifteen patients have developed other cancers after SCT at a median time of 41 months (range, 23-114 months) after transplantation. Four of these patients have developed nonmelanomatous skin cancers at 26 to 109 months after transplantation, and one patient developed melanoma at 25 months after autologous SCT. Nine patients have developed carcinomas at a median of 81 months (range, 28-114 months) after autologous SCT (2 colorectal, 2 breast, 3 lung, one head and neck, and one prostate cancer). Only 2 of these patients also had CLL progression. One patient developed bladder cancer at 23 months after allogeneic SCT but died of progressive CLL.

Second cancers occurring after stem cell transplantation

Type of transplantation and patient UPN . | Protocol . | Time to second cancer, mo . | CLL relapse status . | Status at diagnosis of second cancer . | Status . | Survival after second cancer, mo . | Other cancer . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous | |||||||

| 1583 | 89-064 | 55 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 3 | MDS |

| 1708 | 89-064 | 62 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 28 | MDS |

| 1810 | 89-064 | 40 | No | Remission | Dead | 15 | MDS |

| 1896 | 89-064 | 13 | Yes | Remission | Alive | 102 | MDS |

| 1977 | 94-055 | 28 | No | Remission | Dead | 61 | MDS |

| 2039 | 94-055 | 36 | No | Remission | Alive | 58 | MDS |

| 2168 | 94-055 | 87 | No | Remission | Alive | 1 | MDS |

| 2551 | 94-055 | 11 | Yes | Remission | Dead | 58 | MDS |

| 2658 | 94-055 | 23 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 10 | MDS |

| 2738 | 94-055 | 69 | No | Remission | Alive | 0 | MDS |

| 2739 | 94-055 | 34 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 0 | MDS |

| 3198 | 94-055 | 49 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 2 | MDS |

| 3205 | 94-055 | 26 | No | Remission | Dead | 23 | MDS |

| 1621 | 89-064 | 138 | No | Remission | Alive | 0 | T-cell NHL |

| 2033 | 94-055 | 13 | Yes | Remission | Alive | 87 | B-cell NHL |

| 1600 | 89-064 | 114 | No | Remission | Alive | 26 | Colon |

| 1723 | 89-064 | 103 | No | Remission | Alive | 26 | Breast |

| 1807 | 89-064 | 97 | No | Remission | Alive | 7 | Squamous cell lung |

| 1811 | 89-064 | 81 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 4 | Head and neck |

| 1845 | 89-064 | 60 | Yes | Relapse | Alive | 55 | Breast |

| 1975 | 94-055 | 82 | No | Remission | Alive | 25 | Prostate |

| 2072 | 94-055 | 31 | No | Remission | Dead | 37 | Squamous cell lung |

| 2220 | 94-055 | 41 | No | Remission | Alive | 38 | Anal |

| 3082 | 94-055 | 28 | No | Remission | Dead | 1 | Small cell lung |

| 3028 | 94-055 | 25 | Yes | Remission | Alive | 34 | Melanoma |

| 1828 | 89-064 | 109 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 15 | Basal cell |

| 2142 | 94-055 | 35 | Yes | Remission | Dead | 38 | Squamous cell skin |

| 3109 | 94-055 | 26 | No | Remission | Alive | 24 | Basal cell |

| 3287 | 94-055 | 33 | Yes | Relapse | Alive | 13 | Basal cell |

| Allogeneic | |||||||

| 1595 | 89-064 | 23 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 13 | Bladder |

| 2021 | 94-055 | 1 | No | Remission | Dead | 1 | B-cell NHL |

Type of transplantation and patient UPN . | Protocol . | Time to second cancer, mo . | CLL relapse status . | Status at diagnosis of second cancer . | Status . | Survival after second cancer, mo . | Other cancer . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous | |||||||

| 1583 | 89-064 | 55 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 3 | MDS |

| 1708 | 89-064 | 62 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 28 | MDS |

| 1810 | 89-064 | 40 | No | Remission | Dead | 15 | MDS |

| 1896 | 89-064 | 13 | Yes | Remission | Alive | 102 | MDS |

| 1977 | 94-055 | 28 | No | Remission | Dead | 61 | MDS |

| 2039 | 94-055 | 36 | No | Remission | Alive | 58 | MDS |

| 2168 | 94-055 | 87 | No | Remission | Alive | 1 | MDS |

| 2551 | 94-055 | 11 | Yes | Remission | Dead | 58 | MDS |

| 2658 | 94-055 | 23 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 10 | MDS |

| 2738 | 94-055 | 69 | No | Remission | Alive | 0 | MDS |

| 2739 | 94-055 | 34 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 0 | MDS |

| 3198 | 94-055 | 49 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 2 | MDS |

| 3205 | 94-055 | 26 | No | Remission | Dead | 23 | MDS |

| 1621 | 89-064 | 138 | No | Remission | Alive | 0 | T-cell NHL |

| 2033 | 94-055 | 13 | Yes | Remission | Alive | 87 | B-cell NHL |

| 1600 | 89-064 | 114 | No | Remission | Alive | 26 | Colon |

| 1723 | 89-064 | 103 | No | Remission | Alive | 26 | Breast |

| 1807 | 89-064 | 97 | No | Remission | Alive | 7 | Squamous cell lung |

| 1811 | 89-064 | 81 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 4 | Head and neck |

| 1845 | 89-064 | 60 | Yes | Relapse | Alive | 55 | Breast |

| 1975 | 94-055 | 82 | No | Remission | Alive | 25 | Prostate |

| 2072 | 94-055 | 31 | No | Remission | Dead | 37 | Squamous cell lung |

| 2220 | 94-055 | 41 | No | Remission | Alive | 38 | Anal |

| 3082 | 94-055 | 28 | No | Remission | Dead | 1 | Small cell lung |

| 3028 | 94-055 | 25 | Yes | Remission | Alive | 34 | Melanoma |

| 1828 | 89-064 | 109 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 15 | Basal cell |

| 2142 | 94-055 | 35 | Yes | Remission | Dead | 38 | Squamous cell skin |

| 3109 | 94-055 | 26 | No | Remission | Alive | 24 | Basal cell |

| 3287 | 94-055 | 33 | Yes | Relapse | Alive | 13 | Basal cell |

| Allogeneic | |||||||

| 1595 | 89-064 | 23 | Yes | Relapse | Dead | 13 | Bladder |

| 2021 | 94-055 | 1 | No | Remission | Dead | 1 | B-cell NHL |

Discussion

We describe here the outcome of 162 patients with high-risk CLL who have undergone autologous or allogeneic SCT at a single center. Long-term follow-up is important after experimental treatment approaches for patients with malignancies such as CLL that have such long natural history. These myeloablative regimens were associated with a low short-term treatment-related mortality of 4%, but later relapse and nonrelapse mortality negatively affected outcome. Although there is no clear evidence of a plateau for survival or progression-free survival in this study, 21 patients remain alive, 12 of whom remain disease free and in molecular complete remission more than 8 years after transplantation (J.G.G., unpublished observation, October 2004). In the present study, we observed no evidence that patients who received a transplant in first remission had better outcome than those treated after previous relapse and that there was no improvement in outcome after autologous SCT using combined chemotherapy and monoclonal antibody than those treated with older regimens. It is difficult to assess the effect of transplantation on survival of the patients reported here, but the 6-year overall survival after transplantation of 58% appears better than would be expected in these patients with high-risk CLL, particularly when greater than 90% of these patients had unmutated IgH status.33 It must be stressed, however, that this analysis is not performed on an intent-to-treat basis, and patients were enrolled at the time of achieving eligibility and referral to a transplantation center. These findings in CLL appear similar to those observed in multiple myeloma.34 In this disease setting, although autologous SCT does not appear curative, it is still associated with improved outcome compared with conventional therapy.35

Outcome after transplantation by immunoglobulin heavy chain gene mutational status. (A) Progression-free survival. (B) Overall survival.

Outcome after transplantation by immunoglobulin heavy chain gene mutational status. (A) Progression-free survival. (B) Overall survival.

A number of studies have examined the feasibility and outcome of autologous and allogeneic SCTs in CLL.2,3,5-8 Autologous SCT was feasible in 67% of young patients with CLL who were enrolled in a prospective multicenter study,8 and a retrospective matched pair analysis suggested a survival advantage for autologous SCT over conventional therapy.33 Although we observed no difference in outcome between autologous and allogeneic SCTs in the present study, previous studies have suggested an improved outcome for patients with CLL undergoing allogeneic compared with autologous SCT,3 particularly in patients with poor-risk features such as unmutated IgH status,36,37 suggesting a graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect in this disease that is responsible for the low likelihood of late relapses occurring after allogeneic transplantation for low-grade B-cell malignancies. We performed T-cell depletion to attempt to decrease the morbidity and mortality of allogeneic SCT, and it is likely that this also resulted in loss of the beneficial effect on progression-free survival of the GVL and that the increased late relapses seen here reflect the loss of GVL effect mediated by T-cell depletion. The high subsequent response rate to DLI in CLL supports this conclusion. Only 15% of patients in the present study underwent allogeneic SCT. The reason for this relatively low number of patients with suitable donors likely reflects not only the difficulties of identifying suitable sibling donors in an older age group population, but also a referral bias of patients to our center at a time when other centers were offering allogeneic SCT, so that patients with an HLA-matched donor could be referred to those other centers, whereas patients without donors would still be referred to our institution. In keeping with the known familial incidence in CLL,38 7 potentially suitable HLA-matched donors were excluded when they were found to have evidence of B-cell lymphoproliferative diseases.

Cumulative incidence of MDS and death after autologous stem cell transplantation.

Cumulative incidence of MDS and death after autologous stem cell transplantation.

Nonmelanomatous skin cancers are common in older patients, but there is concern regarding the incidence of other secondary malignancies observed in this study. In particular, the risk of secondary MDS/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) has been observed as a consequence of autologous SCT after high-dose therapy, particularly those including the use of TBI.39-41 We had previously observed a high risk of MDS in patients with follicular NHL after TBI,40 but at that time the incidence appeared low in the patients with CLL. It was therefore possible that either the disease itself, or more likely the different front-line therapy delivered to these patients, may have offered some protection against this complication. It now appears that the risk of secondary MDS is similar after TBI in both NHL and CLL, and that long-term follow-up was required to observe this complication. To date 9 other cancers have occurred after autologous SCT. A higher risk of secondary cancers has been reported after CLL,42,43 and these patients are also more elderly than many series of the use of autologous SCT in other malignancies, so it is presently not possible to state definitively the increased risk of the use of high-dose therapy on these types of cancers. However, we caution that patients who have undergone high-dose therapy require close long-term monitoring to screen for the development of these malignancies.

We conclude that, although the short-term complications of stem cell transplantation after myeloablative-conditioning regimens appear feasible and are associated with low toxicity, on long-term follow-up of these patients there is a high cost in terms of late treatment-related complications, including MDS and other cancers, and that disease progression did not appear to plateau in this population with high-risk CLL. From these findings, the accumulating evidence of a powerful GVL effect in CLL44 and the decreased mortality associated with reduced-intensity conditioning regimen,45 our current approach for patients with high-risk CLL is to perform reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic SCT from related and unrelated donors.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 30, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1778.

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (CA81534) (J.G.G.) and (PO1AI29530) (J.R.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank the staff of the Cell Manipulation Facility at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute for processing the bone marrows and the staff of the Stem Cell Transplant Unit at Brigham and Women's Hospital for their care of these patients.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal