Abstract

The chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) immunoglobulin repertoire is biased and characterized by the existence of subsets of cases with closely homologous (“stereotyped”) complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) sequences. In the present series, 201 (21.9%) of 916 patients with CLL expressed IGHV genes that belonged to 1 of 48 different subsets of sequences with stereotyped heavy chain (H) CDR3. Twenty-six subsets comprised 3 or more sequences and were considered “confirmed.” The remaining subsets comprised pairs of sequences and were considered “potential”; public database CLL sequences were found to be members of 9 of 22 “potential” subsets, thereby allowing us to consider them also “confirmed.” The chance of belonging to a subset exceeded 35% for unmutated or selected IGHV genes (eg, IGHV1-69/3-21/4-39). Comparison to non-CLL public database sequences showed that HCDR3 restriction is “CLL-related.” CLL cases with selected stereotyped immunoglobulins (IGs) were also found to share unique biologic and clinical features. In particular, cases expressing stereotyped IGHV4-39/IGKV1-39-1D-39 and IGHV4-34/IGKV2-30 were always IgG-switched. In addition, IGHV4-34/IGKV2-30 patients were younger and followed a strikingly indolent disease, contrasting other patients (eg, those expressing IGHV3-21/IGLV3-21) who experienced an aggressive disease, regardless of IGHV mutations. These findings suggest that a particular antigen-binding site can be critical in determining the clinical features and outcome for at least some CLL patients.

Introduction

Several lines of evidence indicate that the development of various B-cell malignancies might be influenced by antigen recognition or selection (or both) through their B-cell receptor (BCR). A skewed repertoire of immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable (IGHV) genes has been reported for different types of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders.1-9 This suggests that antigens or superantigens or both may be involved in lymphoma development by stimulating proliferation of B cells that express surface immunoglobulins encoded by particular immunoglobulin genes. Many lymphoma subtypes are characterized by somatic mutation patterns in IGHV genes typical of antigen receptors that have undergone selection by antigen10-13 ; furthermore, for some B-cell malignancies there is evidence for ongoing mutational activity after transformation.14-17 Finally, most lymphoma malignant cells do not survive or proliferate autonomously in vitro, indicating that they are still dependent on external stimuli for their expansion. Although the precise nature of these signals is still largely unknown, in some instances it might involve antigenic stimulation.18

Somatic mutations can be present in immunoglobulin genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and define 2 disease subtypes associated with a different clinical course. CLL cases carrying IGHV genes with less than 98% homology to the closest germline gene (“mutated”) generally follow a more indolent course than those with 98% or more homology (“unmutated”).19,20 The expressed IGHV/IGKV/IGLV gene repertoires of CLL are biased and distinct from those of normal B cells.21-26 Certain immunoglobulin genes (eg, IGHV1-69, IGKV1-33/1D-33, IGLV3-21) are preferentially used in unmutated rearrangements, whereas others (eg, IGHV4-34, IGKV2-30, IGLV2-8) are more frequent in mutated rearrangements. This feature is “CLL-biased,” because it does not appear in the normal repertoire.25,26

Several groups have recently reported subsets of CLL cases carrying closely homologous (“stereotyped”) complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) sequences among both mutated and unmutated cases.25-33 The remarkable BCR similarity in unrelated and geographically distant cases implies the recognition of individual, discrete antigens or classes of structurally similar epitopes, likely selecting the leukemic clones. Along these lines, recent immunophenotypic data suggest that all CLL cells resemble antigen-experienced and activated B cells,24,34 regardless of IGHV mutations.

The nature of the antigens cannot be directly deduced from the immunoglobulin gene sequences; nevertheless, some hints can derive from the analysis of the known specificity of similar antibodies. CLL cells frequently express IgM antibodies that show reactivity to self-antigens (eg, IgG, cardiolipin, actin, thyroglobulin, DNA).35-40 Furthermore, “CLL-biased” homologous subsets have been reported for the IGHV1-69 gene,30-33 which is frequently used by antibodies with rheumatoid factor activity.

In addition to biased immunoglobulin gene usage and mutational status, analysis of CDR3 configuration may also provide important biologic and prognostic information in CLL. This was suggested by 2 independent groups for 2 different subsets of CLL cases with stereotyped BCRs (IGHV4-39/IGKV1-39-1D-39, IGHV3-21/IGLV3-21), which exhibited distinctive features with regard to demographics, immunophenotype, and outcome.25,29

In the current study, we report that stereotyped CDR3s are in fact present in a much larger proportion of patients with CLL than expected. We describe 48 different subsets of IGHV-D-J sequences with homologous heavy-chain CDR3 (HCDR3) among 916 patients with CLL of Mediterranean origin. Irrespective of IGHV usage, 201 of 916 cases from our series (21.9%) belonged to a subset of sequences with stereotyped HCDR3. Comparison to a large collection of public database non-CLL sequences strongly indicates that this feature is “CLL-biased.” Finally, we show that CLL cases expressing stereotyped immunoglobulins may also share unique molecular and clinical features, thus further supporting the notion that a particular antigen-binding site can make a difference in terms of clinical presentation and possibly also prognosis.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patient group

A total of 916 patients with CLL from different institutions in France (297 cases), Greece (381 cases), Italy (146 cases), and Spain (92 cases) were studied for IGHV repertoire and mutational status. All cases were immunophenotyped as previously described24 and met the diagnostic criteria of the National Cancer Institute Working Group (NCI-WG).41 Written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki was obtained at study entry from all patients. The study was approved by the local Ethics Review Committee of each institution.

Within this cohort, the following parameters measured at diagnosis or during follow-up were evaluated: CD38 expression (7% cut-off for positivity42,43 ), IGHV mutation status, immunoglobulin isotype-switched status, immunoglobulin light-chain rearrangement, disease stage at diagnosis, need for treatment, and progressive or stable disease as defined by the NCI-WG.41 Comparative analysis of “stereotyped HCDR3” versus “heterogeneous HCDR3” cases was undertaken for subsets with 8 or more cases to allow statistical analysis.

PCR amplification of immunoglobulin rearrangements and sequence analysis

The analysis of IGHV-D-J genes was done on leukemic cells obtained from peripheral-blood samples after isolation on Ficoll gradient. gDNA and total cellular RNA isolation and cDNA preparation were performed as previously described.25,26 Amplification and sequence analysis of IGH/IGK/IGL rearrangements by DNA-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was performed as previously described25,26 or according to BIOMED-2 protocols.44 Although sequence data were analyzed on at least 2 databases (IMGT, IgBlast, V-BASE), results are reported following the IMGT database (http://imgt.cines.fr),45,46 which is the most comprehensive and more regularly updated database. For identification of IGHD genes, HCDR3 sequences were analyzed using the IMGT/Junction Analysis tool, following established IMGT criteria.47 Sequences with a germline homology of 98% or higher were considered as unmutated, and those with a homology less than 98% were considered as mutated.19,20 The repertoire and mutational status of 553 sequences were published previously.25

Identification of cases with homologous HCDR3 and database searches

Various criteria were used to define subsets of similar rearranged IGHV-D-J sequences. First, we followed the criteria proposed by Messmer et al31 : usage of the same IGHV/D/J germline genes, usage of the same IGHD gene reading frame, and HCDR3 amino acid identity 60% or more. At a second stage, sequences were clustered based on particular HCDR3 amino acid motifs to identify cases with homologous HCDR3s (always with ≥ 60% amino acid identity), regardless of the usage of different IGHV genes. Recurrent HCDR3 motifs from the various subsets thus identified were used to search the public databases. Amino acid differences at the same HCDR3 position in cases belonging to a subset were evaluated based on amino acid physicochemical properties (hydropathy, volume, and chemical characteristics).48

CLL sequences from our series were aligned to a comprehensive panel of sequences available from literature or retrieved in August 2005 from the IMGT/LIGM-DB sequence database (http://imgt.cines.fr/cgi-bin/IMGTlect.jv?). Stringent criteria were followed so that redundant, poorly annotated, out-of-frame, incomplete sequences, or sequences from clonally related cells carrying identical HCDR3s were not included in the alignment analysis. Thus, a collection of 6892 unique HCDR3 sequences became available for HCDR3 alignment studies (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Tables link at the top of the online article). Public collection sequences are categorized in Table 1 Specifically, the public data set comprised: (1) 962 sequences from B-cell lymphoproliferations, including: CLL, n = 462; lymphoma, n = 379; other, n = 121; (2) 4066 sequences from normal B cells; (3) 1275 sequences from autoreactive cells; and (4) 589 sequences from “immune dysregulation” conditions (allergy, asthma, various types of immunodeficiency, EBV-infected B cells in angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy).

Categories of 6892 public database (GenBank) sequences used for comparison analysis

| Category . | No. . |

|---|---|

| B-cell lymphoproliferation | 962 |

| CLL | 462 |

| Lymphoma | 379 |

| Multiple myeloma/MGUS | 59/7 |

| EBV-related, after transplantation | 55 |

| Normal B cells | 4066 |

| Peripheral blood | 1179 |

| Peripheral blood/tonsillar, CD5+ | 229/14 |

| Tonsillar/monocytoid/marginal zone | 194/69/49 |

| Thymic | 37 |

| Neonatal/fetal | 884/13 |

| Plasma cells | 705 |

| Various antimicrobial repertoires | 693 |

| Immune dysregulation | 589 |

| Allergy/asthma | 334 |

| Immunodeficiency | 104 |

| EBV-infected B cells in AILD | 151 |

| Autoreactive | 1275 |

| Rheumatoid factors | 673 |

| Anti-DNA antibodies | 76 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 157 |

| Other | 369 |

| Category . | No. . |

|---|---|

| B-cell lymphoproliferation | 962 |

| CLL | 462 |

| Lymphoma | 379 |

| Multiple myeloma/MGUS | 59/7 |

| EBV-related, after transplantation | 55 |

| Normal B cells | 4066 |

| Peripheral blood | 1179 |

| Peripheral blood/tonsillar, CD5+ | 229/14 |

| Tonsillar/monocytoid/marginal zone | 194/69/49 |

| Thymic | 37 |

| Neonatal/fetal | 884/13 |

| Plasma cells | 705 |

| Various antimicrobial repertoires | 693 |

| Immune dysregulation | 589 |

| Allergy/asthma | 334 |

| Immunodeficiency | 104 |

| EBV-infected B cells in AILD | 151 |

| Autoreactive | 1275 |

| Rheumatoid factors | 673 |

| Anti-DNA antibodies | 76 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 157 |

| Other | 369 |

MGUS indicates monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; AILD, angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. See also Table S1 for the GenBank sequences used.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the presentation of data in terms of frequency distributions (discrete variables) and mean, median values (quantitative variables). Overall survival was measured from enrollment to death or last follow-up. Overall survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan-Meier method. Bivariate differences in survival distributions were studied with the use of the log-rank test.

Results

An overview of the IGHV repertoire and HCDR3 features

A total of 927 in-frame IGHV-D-J rearrangements were sequenced in 916 CLL patients; 11 cases carried double in-frame rearrangements (in keeping with a previous report49 ). IGHV, IGHD, and IGHJ subgroup and gene usage was similar to what was previously shown25 and is reported in Tables S2-S4. Using the 98% homology cut-off value,19,20,50 534 (57.6%) of 927 sequences had less than 98% homology and were considered as mutated (365 of 534 with < 95% homology), whereas the remainder (393 of 927; 42.4%) had 98% or greater homology and were considered as unmutated (258 of 393 had 100% homology; Table S2).

IGHD genes were identified in 898 of 927 sequences. A significant overrepresentation of IGHJ4 was observed in mutated rearrangements (P < .001); in contrast, IGHJ6 was overrepresented in unmutated rearrangements (P < .001). HCDR3 median length was 16 amino acids (range, 5-32). Significantly longer HCDR3s were observed in unmutated versus mutated sequences (median lengths, 20 versus 15 amino acids; P < .001) and also in rearrangements using the IGHJ6 versus other IGHJ genes, regardless of IGHV mutation status (median lengths 20 versus 15 amino acids; P < .001).

Subsets of CLL cases with stereotyped HCDR3

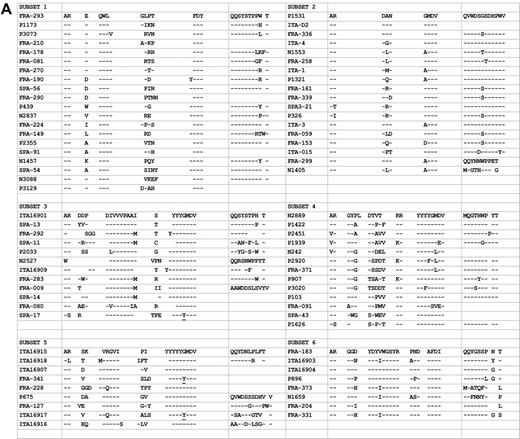

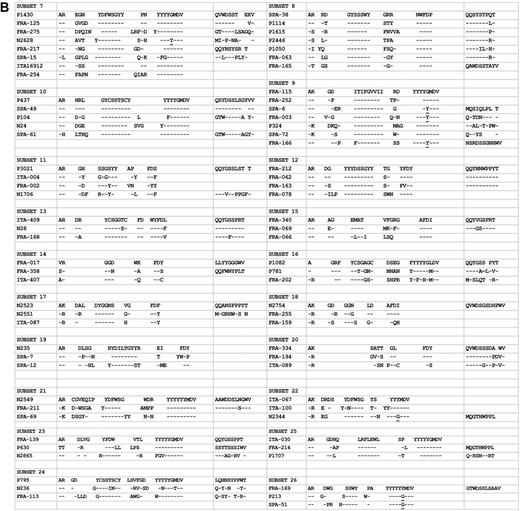

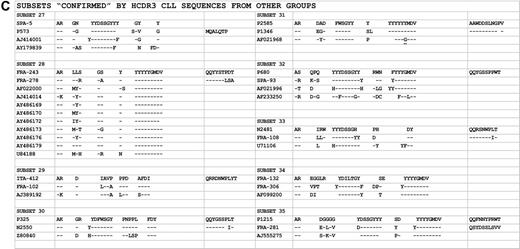

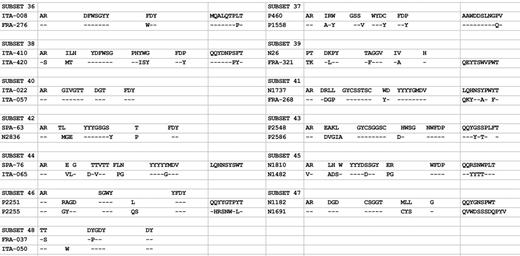

Cluster analysis of sequences from the present series allowed us to identify 201 of 916 cases (21.9%) as belonging to 48 different subsets with stereotyped HCDR3 (Table 2 and S5), of which only 10 have been reported previously.25-33 Within each stereotyped HCDR3 subset, the sequences might show the usage of identical or different IGHV genes (Table 2; Figures 1-2). In the latter case, the IGHV genes most often belonged to the same subgroup or clan51 or carried homologous HCDR1. Each subset included from 2 up to 20 cases (Figures 1-2).

HCDR3 and K/LCDR3 sequences of subsets with 3 or more cases (“confirmed”). Accession numbers are provided for all IGHV-D-J sequences from CLL cases reported by other investigators and available in public databases that “confirmed” subsets 27 to 35 of the present series.

HCDR3 and K/LCDR3 sequences of subsets with 3 or more cases (“confirmed”). Accession numbers are provided for all IGHV-D-J sequences from CLL cases reported by other investigators and available in public databases that “confirmed” subsets 27 to 35 of the present series.

Subsets of CLL cases of the present series with stereotyped HCDR3 sequences. The asterisks denote previously published subsets

| Set . | N . | IGHV gene† . | IGHD gene‡ (reading frame) . | IGHJ gene§ . | Average Intra-subset homology‖ . | IGKV/IGLV gene (no. cases with indicated gene/total no. cases with available data) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed subsets | ||||||

| 1* | 20 | IGHV1-18 (4), IGHV1-2 (4), IGHV1-3 (8), IGHV5-a (3) | IGHD6-19 (3) | IGHJ4 | 71.2 | IGKV1-39/IGKV1D-39 (15/15) |

| 2* | 18 | IGHV3-21 (16), IGHV3-11 (1), IGHV3-48 (1) | ND | IGHJ6 | 85.2 | IGLV3-21 (15/17) |

| 3* | 12 | IGHV1-69 (9), IGHV1-2 (1), IGHV1-8 (1), IGHV4-34 (1) | IGHD2-2 (3) | IGHJ6 | 82.2 | IGKV1-39/IGKV1D-39 (3/9), IGKV3-11 (3/9) |

| 4* | 13 | IGHV4-34 | IGHD5-5 (1)/D4-17 (3) | IGHJ6 | 75.4 | IGKV2-30 (11/11) |

| 5* | 10 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-10 (3) | IGHJ6 | 78.3 | IGKV1-33/IGKV1D-33 (2/7), IGLV3-21 (2/7) |

| 6* | 8 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-16 (2) | IGHJ3 | 92.3 | IGKV3-20 (6/8) |

| 7* | 8 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 64.8 | IGLV3-9 (2/6) |

| 8* | 7 | IGHV4-39 | IGHD6-13 (1) | IGHJ5 | 69.9 | IGKV1-39/IGKV1D-39 (6/7) |

| 9 | 7 | IGHV1-69 (4), IGHV3-21 (1), IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-30 (1) | IGHD3-3 (3) | IGHJ6 | 76.4 | diverse |

| 10 | 5 | IGHV4-39 (4), IGHV2-5 (1) | IGHD2-2 (2) | IGHJ6 | 74.4 | IGLV1-40 (2/5), IGLV1-51 (2/5) |

| 11 | 4 | IGHV4-34 (3), IGHV4-59 (1) | IGHD3-10 (2) | IGHJ4 | 68.3 | IGKV3-20 (2/2) |

| 12 | 4 | IGHV1-2 (3), IGHV1-46 (1) | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ4 | 76.1 | IGKV3-15 (3/3) |

| 13 | 3 | IGHV4-59 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ2 | 90.7 | IGKV3-20 (3/3) |

| 14 | 3 | IGHV4-4 | IGHD2-21 (2) | IGHJ4 | 76.7 | diverse |

| 15 | 3 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD5-24 (1) | IGHJ3 | 74.5 | IGKV3-20 (2/2) |

| 16 | 3 | IGHV4-34 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ6 | 70.8 | diverse |

| 17 | 3 | IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-33 (1), IGHV3-7 (1) | IGHD4-23 (2) | IGHJ4 | 77.1 | diverse |

| 18 | 3 | IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-48(1), IGHV3-11 (1) | IGHD4-23 (2) | IGHJ3 | 84.6 | NA |

| 19 | 3 | IGHV1-69 (2), IGHV3-74 (1) | IGHD3-9 (2) | IGHJ4 | 65.1 | NA |

| 20 | 3 | IGHV3-53 | ND | IGHJ4 | 60.6 | IGLV3-21 (3/3) |

| 21 | 3 | IGHV3-11 (1), IGHV3-23 (2) | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 64.3 | IGLV1-44/47 (2/2) |

| 22 | 3 | IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-21 (1), IGHV3-11 (1) | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 76.2 | NA |

| 23 | 3 | IGHV3-30 (1), IGHV3-15 (1), IGHV3-66 (1) | IGHD3-9 (1) | IGHJ6 | 71.2 | diverse |

| 24 | 3 | IGHV1-2 (2), IGHV4-4 (1) | IGHD2-2 (2) | IGHJ6 | 70.4 | diverse |

| 25 | 3 | IGHV1-8 (1), IGHV3-11 (2) | IGHD3-3 (1) | IGHJ6 | 70.8 | diverse |

| 26 | 3 | IGHV4-b (1), IGHV1-69 (1), IGHV3-66 (1) | IGHD6-13 (1) | IGHJ6 | 80 | NA |

| Subsets confirmed by public database cell sequences from other group¶ | ||||||

| 27 | 2 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ4 | 75 | NA |

| 28* | 2 | IGHV1-2 | IGHD1-26 (1) | IGHJ6 | 88.2 | IGKV4-1 (2/2) |

| 29 | 2 | IGHV4-34 | IGHD6-19 (2) | IGHJ3 | 85.7 | NA |

| 30 | 2 | IGHV3-9 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ4 | 94.7 | IGKV3-20 (2/2) |

| 31 | 2 | IGHV3-48 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 80.9 | IGLV1-44 (2/2) |

| 32 | 2 | IGHV3-48 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ6 | 80 | NA |

| 33 | 2 | IGHV4-39 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ4 | 70.6 | IGKV3-11 (2/2) |

| 34 | 2 | IGHV1-69 (1), IGHV1-18 (1) | IGHD3-9 (2) | IGHJ6 | 69.2 | NA |

| 35 | 2 | IGHV1-69 (1), IGHV3-21 (1) | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ6 | 76 | diverse |

| Potential subsets | ||||||

| 36 | 2 | IGHV3-30 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ4 | 91.7 | IGKV2-28/2D-28 (2/2) |

| 37* | 2 | IGHV4-b | IGHD6-13 (1) | IGHJ4 | 60 | IGLV1-44 (2/2) |

| 38 | 2 | IGHV4-39 (2), IGHV4-59 (1) | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ5 | 61 | IGKV1-33/IGKV1D-33 (2/2) |

| 39 | 2 | IGHV3-1 | IGHD3-16 (3) | IGHJ1 | 64.3 | NA |

| 40 | 2 | IGHV3-33 (1), IGHV3-30 (1) | IGHD1-26 (1) | IGHJ4 | 100 | NA |

| 41 | 2 | IGHV3-21 (1), IGHV3-48 (1) | IGHD2-2 (2) | IGHJ6 | 79.2 | diverse |

| 42 | 2 | IGHV2-70 | IGHD3-10 (2) | IGHJ4 | 68.7 | NA |

| 43 | 2 | IGHV3-33 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ5 | 65.2 | diverse |

| 44 | 2 | IGHV3-48 | IGHD4-23 (3) | IGHJ6 | 65 | NA |

| 45 | 2 | IGHV4-39 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ5 | 63.2 | diverse |

| 46 | 2 | IGHV4-b (1), IGHV3-23 (1) | IGHD6-19 (1) | IGHJ4 | 71.4 | diverse |

| 47 | 2 | IGHV3-66 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ5 | 78.6 | diverse |

| 48 | 2 | IGHV3-74 (1), IGHV3-15 (1) | IGHD4-17 (2) | IGHJ4 | 66.7 | NA |

| Set . | N . | IGHV gene† . | IGHD gene‡ (reading frame) . | IGHJ gene§ . | Average Intra-subset homology‖ . | IGKV/IGLV gene (no. cases with indicated gene/total no. cases with available data) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed subsets | ||||||

| 1* | 20 | IGHV1-18 (4), IGHV1-2 (4), IGHV1-3 (8), IGHV5-a (3) | IGHD6-19 (3) | IGHJ4 | 71.2 | IGKV1-39/IGKV1D-39 (15/15) |

| 2* | 18 | IGHV3-21 (16), IGHV3-11 (1), IGHV3-48 (1) | ND | IGHJ6 | 85.2 | IGLV3-21 (15/17) |

| 3* | 12 | IGHV1-69 (9), IGHV1-2 (1), IGHV1-8 (1), IGHV4-34 (1) | IGHD2-2 (3) | IGHJ6 | 82.2 | IGKV1-39/IGKV1D-39 (3/9), IGKV3-11 (3/9) |

| 4* | 13 | IGHV4-34 | IGHD5-5 (1)/D4-17 (3) | IGHJ6 | 75.4 | IGKV2-30 (11/11) |

| 5* | 10 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-10 (3) | IGHJ6 | 78.3 | IGKV1-33/IGKV1D-33 (2/7), IGLV3-21 (2/7) |

| 6* | 8 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-16 (2) | IGHJ3 | 92.3 | IGKV3-20 (6/8) |

| 7* | 8 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 64.8 | IGLV3-9 (2/6) |

| 8* | 7 | IGHV4-39 | IGHD6-13 (1) | IGHJ5 | 69.9 | IGKV1-39/IGKV1D-39 (6/7) |

| 9 | 7 | IGHV1-69 (4), IGHV3-21 (1), IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-30 (1) | IGHD3-3 (3) | IGHJ6 | 76.4 | diverse |

| 10 | 5 | IGHV4-39 (4), IGHV2-5 (1) | IGHD2-2 (2) | IGHJ6 | 74.4 | IGLV1-40 (2/5), IGLV1-51 (2/5) |

| 11 | 4 | IGHV4-34 (3), IGHV4-59 (1) | IGHD3-10 (2) | IGHJ4 | 68.3 | IGKV3-20 (2/2) |

| 12 | 4 | IGHV1-2 (3), IGHV1-46 (1) | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ4 | 76.1 | IGKV3-15 (3/3) |

| 13 | 3 | IGHV4-59 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ2 | 90.7 | IGKV3-20 (3/3) |

| 14 | 3 | IGHV4-4 | IGHD2-21 (2) | IGHJ4 | 76.7 | diverse |

| 15 | 3 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD5-24 (1) | IGHJ3 | 74.5 | IGKV3-20 (2/2) |

| 16 | 3 | IGHV4-34 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ6 | 70.8 | diverse |

| 17 | 3 | IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-33 (1), IGHV3-7 (1) | IGHD4-23 (2) | IGHJ4 | 77.1 | diverse |

| 18 | 3 | IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-48(1), IGHV3-11 (1) | IGHD4-23 (2) | IGHJ3 | 84.6 | NA |

| 19 | 3 | IGHV1-69 (2), IGHV3-74 (1) | IGHD3-9 (2) | IGHJ4 | 65.1 | NA |

| 20 | 3 | IGHV3-53 | ND | IGHJ4 | 60.6 | IGLV3-21 (3/3) |

| 21 | 3 | IGHV3-11 (1), IGHV3-23 (2) | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 64.3 | IGLV1-44/47 (2/2) |

| 22 | 3 | IGHV3-23 (1), IGHV3-21 (1), IGHV3-11 (1) | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 76.2 | NA |

| 23 | 3 | IGHV3-30 (1), IGHV3-15 (1), IGHV3-66 (1) | IGHD3-9 (1) | IGHJ6 | 71.2 | diverse |

| 24 | 3 | IGHV1-2 (2), IGHV4-4 (1) | IGHD2-2 (2) | IGHJ6 | 70.4 | diverse |

| 25 | 3 | IGHV1-8 (1), IGHV3-11 (2) | IGHD3-3 (1) | IGHJ6 | 70.8 | diverse |

| 26 | 3 | IGHV4-b (1), IGHV1-69 (1), IGHV3-66 (1) | IGHD6-13 (1) | IGHJ6 | 80 | NA |

| Subsets confirmed by public database cell sequences from other group¶ | ||||||

| 27 | 2 | IGHV1-69 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ4 | 75 | NA |

| 28* | 2 | IGHV1-2 | IGHD1-26 (1) | IGHJ6 | 88.2 | IGKV4-1 (2/2) |

| 29 | 2 | IGHV4-34 | IGHD6-19 (2) | IGHJ3 | 85.7 | NA |

| 30 | 2 | IGHV3-9 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ4 | 94.7 | IGKV3-20 (2/2) |

| 31 | 2 | IGHV3-48 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ6 | 80.9 | IGLV1-44 (2/2) |

| 32 | 2 | IGHV3-48 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ6 | 80 | NA |

| 33 | 2 | IGHV4-39 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ4 | 70.6 | IGKV3-11 (2/2) |

| 34 | 2 | IGHV1-69 (1), IGHV1-18 (1) | IGHD3-9 (2) | IGHJ6 | 69.2 | NA |

| 35 | 2 | IGHV1-69 (1), IGHV3-21 (1) | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ6 | 76 | diverse |

| Potential subsets | ||||||

| 36 | 2 | IGHV3-30 | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ4 | 91.7 | IGKV2-28/2D-28 (2/2) |

| 37* | 2 | IGHV4-b | IGHD6-13 (1) | IGHJ4 | 60 | IGLV1-44 (2/2) |

| 38 | 2 | IGHV4-39 (2), IGHV4-59 (1) | IGHD3-3 (2) | IGHJ5 | 61 | IGKV1-33/IGKV1D-33 (2/2) |

| 39 | 2 | IGHV3-1 | IGHD3-16 (3) | IGHJ1 | 64.3 | NA |

| 40 | 2 | IGHV3-33 (1), IGHV3-30 (1) | IGHD1-26 (1) | IGHJ4 | 100 | NA |

| 41 | 2 | IGHV3-21 (1), IGHV3-48 (1) | IGHD2-2 (2) | IGHJ6 | 79.2 | diverse |

| 42 | 2 | IGHV2-70 | IGHD3-10 (2) | IGHJ4 | 68.7 | NA |

| 43 | 2 | IGHV3-33 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ5 | 65.2 | diverse |

| 44 | 2 | IGHV3-48 | IGHD4-23 (3) | IGHJ6 | 65 | NA |

| 45 | 2 | IGHV4-39 | IGHD3-22 (2) | IGHJ5 | 63.2 | diverse |

| 46 | 2 | IGHV4-b (1), IGHV3-23 (1) | IGHD6-19 (1) | IGHJ4 | 71.4 | diverse |

| 47 | 2 | IGHV3-66 | IGHD2-15 (2) | IGHJ5 | 78.6 | diverse |

| 48 | 2 | IGHV3-74 (1), IGHV3-15 (1) | IGHD4-17 (2) | IGHJ4 | 66.7 | NA |

N indicates number of cases; ND, not determined; NA, not available.

Previously published subsets.

The relative frequencies of stereotyped HCDR3s were significantly different among rearrangements using IGHV1 versus IGHV3 versus IGHV4 subgroup genes (34% versus 15% versus 23%; P < .001).

An increased frequency of IGHD6 subgroup genes (P = .05) as well as a decreased frequency of IGHD1 subgroup genes (P < .01) was observed among stereotyped HCDR3 cases.

IGHJ4 was found at a decreased frequency and IGHJ6 at an increased frequency in rearrangements with stereotyped HCDR3s (29% versus 53%, respectively; P < .01).

The percentage of HCDR3 amino acid identity was evaluated pair-wise for all members of a subset and used to calculate the average intra-subset HCDR3 homology. In the case of subset nos. 34 and 40, some pairs of sequences had >55% but <60% amino acid identity; however, different amino acids often shared similar properties. Furthermore, both subsets were characterized by restricted light-chain usage and CDR3.

HCDR3 public-database CLL sequences from other groups that “confirmed” the existence of subsets of the present series with two members only are shown in Figure 1 and in Tables S5-S6.

Twenty-six of 48 subsets comprised 3 cases or more and, as in previous studies,32 may be considered as true subsets and thus are defined as “confirmed” (Figure 1). Light-chain data were available for 22 of 26 “confirmed” subsets and revealed restricted light-chain usage for 15 subsets. In 2 of 7 remaining subsets with diverse IGKV or IGLV genes (nos. 9 and 23), 55% and 50% CDR3 sequence identity was observed among IGK/IGL sequences, respectively.

Twenty-two of all 48 subsets comprised 2 cases each and might be considered “potential,” as the possibility that their similarity may occur for serendipity cannot be a priori excluded. Interestingly, several IGHV-D-J CLL sequences, available in public databases, were found to be members of 9 of 22 “potential” subsets reported in the present article, thereby allowing consideration of them also as “confirmed” (Figure 1). Light-chain data were available for 5 of 9 subsets “confirmed” by public database CLL sequences and revealed restricted light-chain usage in 4 subsets.

Three of 13 actual “potential” subsets (Figure 2) were characterized by restricted light-chain CDR3; 3 other subsets shared junctional residues. The remaining 7 “potential” subsets had limited junctional identity but carried identical IGHV/IGHD/IGHJ or IGHD/IGHJ genes.

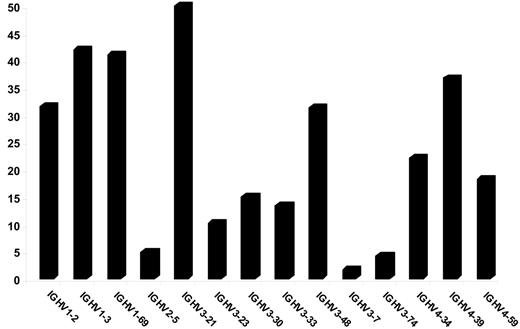

Molecular features of cases with stereotyped HCDR3

Of 393 unmutated sequences from our series, 140 (35.4%) belonged to a subset. Among sequences with 100% IGHV homology, the chance of belonging to a subset with stereotyped HCDR was even higher (106 of 258 cases; 41%); in contrast, only 61 of 534 (11.4%) IGHV-mutated sequences belonged to a subset with stereotyped HCDR3. The difference in the frequency of carrying a stereotyped HCDR3 among unmutated versus mutated sequences was statistically significant (P < .001). The relative frequencies of stereotyped HCDR3s differed significantly among rearrangements using IGHV1 versus IGHV3 versus IGHV4 subgroup genes (34% versus 15% versus 23%; P < .001). In addition, this frequency exceeded 30% in cases using particular IGHV genes (eg, IGHV3-21, IGHV1-69, IGHV1-2, IGHV1-3, IGHV4-39, IGHV3-48); in contrast, it was less than 5% for other IGHV genes (eg, IGHV3-7, IGHV3-74, IGHV2-5) as shown in Figure 3.

Somatic mutation analysis: recurrent, “subset-biased” mutations

Ninety-five (47.2%) of 201 IGHV-D-J sequences belonging to subsets had less than 100% homology to germline; 61 (64.2%) of 95 sequences had less than 98% homology. Somatic mutation status was concordant for heavy and light chains in all except one case with available data (Table S4).

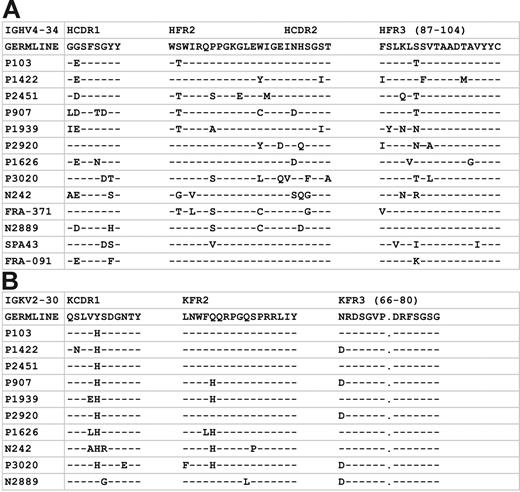

Several “mutated” subsets showed shared replacement mutations (ie, the same amino acid replacement at the same position). Particularly noteworthy in this respect is subset no. 4, which comprises 13 cases expressing stereotyped IGHV4-34/IGKV2-30 BCRs (Figure 4) Comparison to 589 public database IGHV4-34 sequences from CLL, autoreactive cells, normal plasma cells, or marginal zone B cells (Table S1) revealed that subset no. 4 somatic hypermutation patterns were “subset-biased.”

Replacement mutations in IGHV and IGKV sequences of subset no. 4. (A) Shared mutations in rearranged IGHV4-34 genes expressed by subset no. 4 cases. (i) IMGT-CDR1 codon 28: Gly→Asp/Glu, 9 of 13 cases; (ii) IMGT-FR2 codon 40: Ser→Thr, 5 of 13 cases; (iii) IMGT-FR2 codon 45: Pro→Ser, 4 of 13 cases; (iv) IMGT-FR3 codon 92: Ser→Thr, 4 of 13 cases. (B). Shared mutations in rearranged IGKV2-30 genes expressed by subset no. 4 cases. (1) IMGT-CDR1 codon 31: Tyr→His, 9 of 10 cases; (2) IMGT-FR2 codon 43: Gln→His, 5 of 10 cases; (3) IMGT-FR3 codon 66: Asn→Asp, 5 of 10 cases.

Replacement mutations in IGHV and IGKV sequences of subset no. 4. (A) Shared mutations in rearranged IGHV4-34 genes expressed by subset no. 4 cases. (i) IMGT-CDR1 codon 28: Gly→Asp/Glu, 9 of 13 cases; (ii) IMGT-FR2 codon 40: Ser→Thr, 5 of 13 cases; (iii) IMGT-FR2 codon 45: Pro→Ser, 4 of 13 cases; (iv) IMGT-FR3 codon 92: Ser→Thr, 4 of 13 cases. (B). Shared mutations in rearranged IGKV2-30 genes expressed by subset no. 4 cases. (1) IMGT-CDR1 codon 31: Tyr→His, 9 of 10 cases; (2) IMGT-FR2 codon 43: Gln→His, 5 of 10 cases; (3) IMGT-FR3 codon 66: Asn→Asp, 5 of 10 cases.

Stereotyped HCDR3s and clinical-biologic associations

We compared clinical and biologic features of “stereotyped HCDR3” versus “heterogeneous HCDR3” cases. In particular instances, CLL cases with stereotyped HCDR3 sequences were found to share unique phenotypic features and also marked similarities in terms of clinical outcome, ranging from an aggressive disease associated with short survival to a strikingly indolent disease with prolonged survival.

“Mixed IGHV1/5” subset (subset no. 1).

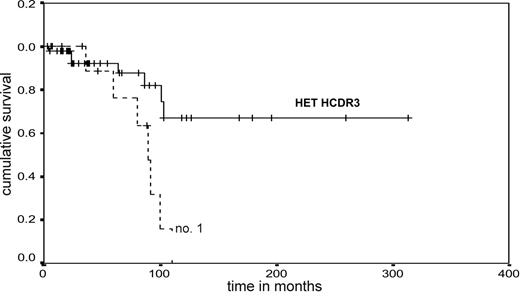

A subset (no. 1) of 20 cases with stereotyped HCDR3s, which used IGHV genes of the same clan (IGHV1-2/IGHV1-3/IGHV1-18 or IGHV5-a), was identified among 79 cases expressing the aforementioned IGHV genes. Stereotyped HCDR3 cases were comparable with heterogeneous HCDR3 cases with regard to age and clinical stage at diagnosis. All patients of subset no. 1 carried unmutated IGHV genes, used IGKV1-39/1D-39 κ light chains with stereotyped KCDRs, and, except for one case, were CD38+. Their prognosis was poor; in particular, 11 of 15 patients with available data had progressive disease and 8 of 15 died of CLL-related causes (median survival, 84 months). In contrast, “non-subset no. 1” cases expressing IGHV1-2/1-3/1-18/5-a were characterized by diverse IGV light-chain gene usage, variable IGHV mutational status (only 29 of 9 IGHV-unmutated cases; P < .001 for comparison to subset no. 1), heterogeneous CD38 expression (15 of 34 CD38+ cases; P = .001), and variable clinical course. As compared to subset no. 1, only 18 of 48 “non-subset no. 1” cases had progressive disease (P = .02), whereas only 7 of 48 patients died of CLL-related causes (median survival, 234 months; log-rank test = 0.0045; Figure 5)

Survival curves. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves comparing CLL cases of subset no. 1, which expressed different genes of the IGHV1 or IGHV5 subgroups (IGHV1-2/IGHV1-3/IGHV1-18 or IGHV5-a), versus CLL cases expressing the aforementioned IGHV with heterogeneous HCDR3 sequences (HET HCDR3) (log-rank test = 0.0048).

Survival curves. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves comparing CLL cases of subset no. 1, which expressed different genes of the IGHV1 or IGHV5 subgroups (IGHV1-2/IGHV1-3/IGHV1-18 or IGHV5-a), versus CLL cases expressing the aforementioned IGHV with heterogeneous HCDR3 sequences (HET HCDR3) (log-rank test = 0.0048).

IGHV1-69 subsets (subset nos. 3, 5-7, 9, 15, 19, 27).

Forty-five of 115 cases expressing IGHV1-69 (38.3%) from our series carried restricted HCDR3s and could be grouped into 8 different subsets (nos. 3, 5-7, 9, 15, 19, 27). All cases belonging to these subsets were unmutated, except those from subset no. 15.

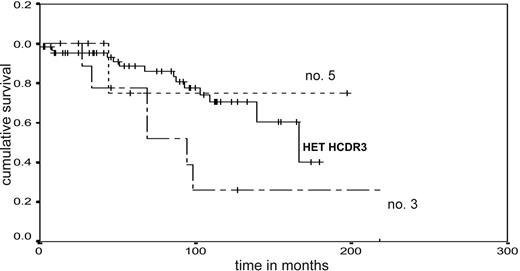

Stereotyped HCDR3 cases were comparable with heterogeneous HCDR3 cases regarding age, clinical stage at diagnosis, CD38 expression, and clinical progression rate. When considering all IGHV1-69expressing cases together, 25 of 81 cases evaluable for outcome (follow-up time > 6 months) died of CLL-related causes (median survival, 110 months). Of note, cases belonging to subset no. 5 (IGHV1-69/IGHD3-10/IGHJ6) seem to be associated with a more indolent disease. In contrast, cases belonging to subset no. 3 (IGHV1-69/IGHD2-2/IGHJ6) seem to be associated with a more aggressive disease. In particular, at the end of the study, 7 of 8 patients in subset no. 5 are alive (median survival not yet reached), compared to only 2 of 9 in subset no. 3 (median survival, 94 months; log-rank test = 0.05), despite a similar mean follow-up time (Figure 6).

Survival curves. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves comparing IGHV1-69–expressing CLL cases of subset no. 3 versus IGHV1-69–expressing CLL cases of subset no. 5 versus IGHV1-69–expressing CLL cases with heterogeneous HCDR3 sequences (HET HCDR3) (log-rank test = 0.045).

Survival curves. Kaplan-Meier overall survival curves comparing IGHV1-69–expressing CLL cases of subset no. 3 versus IGHV1-69–expressing CLL cases of subset no. 5 versus IGHV1-69–expressing CLL cases with heterogeneous HCDR3 sequences (HET HCDR3) (log-rank test = 0.045).

IGHV3-21 subset (subset no. 2).

Sixteen of 32 cases (50%) expressing IGHV3-21 in our series carried stereotyped HCDR3s (subset no. 2). Fourteen cases were associated with homologous IGLV3-21 light chains, as previously described.25,28,52-55 Ten of 12 analyzed cases (71.5%) expressed CD38. In contrast, “heterogeneous HCDR3” IGHV3-21 cases were characterized by diverse IGV light-chain gene usage and heterogeneous CD38 expression.

Stereotyped HCDR3 cases were comparable with heterogeneous HCDR3 cases regarding age and clinical stage at diagnosis. In keeping with our previous observations,25 progressive disease was significantly more frequent among stereotyped IGHV3-21 cases; clinical progression was observed in 14 of 15 stereotyped versus 6 of 13 heterogeneous IGHV3-21 cases, after a median follow-up of 40 and 36 months, respectively (P = .008). At the end of study, 7 of 13 stereotyped versus 1 of 11 heterogeneous patients died of CLL-related causes. Nevertheless, the OS was not statistically different between the 2 groups (median survival, 60 months for stereotyped cases versus not yet reached for heterogeneous cases; log-rank test = 0.24).

IGHV4-34 subsets (subset nos. 4, 11, 16, 29).

Among 95 cases expressing IGHV4-34 in the present series, 4 subsets (nos. 4, 11, 16, 29) of collectively 21 mutated sequences with different, restricted HCDR3s were identified. The main subset (subset no. 4) comprised 13 cases, all associated with stereotyped IGKV2-30 light chains. This association is “subset no. 4-biased,” as the IGKV2-30 gene was expressed by only 1 of 36 “non-subset no. 4” IGHV4-34 cases (P < .001). All cases with available data (n = 10) are IgG-switched (versus only 13 of 60 non-subset no. 4 IGHV4-34 cases; P < .001).

Stereotyped HCDR3 cases were comparable with heterogeneous HCDR3 cases regarding clinical stage at diagnosis. Subset no. 4 comprised young patients with a median age at diagnosis of 43 years; in comparison, “non-subset no. 4” IGHV4-34–expressing cases had a median age of 63 years (P = .003). Subset no. 4 cases followed a strikingly indolent disease compared to heterogeneous IGHV4-34 cases (in line with the fact that they were all CD38− [13 of 13 versus 16 of 52 “non-subset no. 4” IGHV4-34 cases; P = .04]). In particular, progressive disease requiring treatment was observed in only 3 of 13 subset no. 4 cases (23%) versus 29 of 63 “non-subset no. 4” IGHV4-34 cases (46%). Furthermore, at the last follow-up, only 1 of 13 subset no. 4 cases (7.7%) died of CLL-related causes (versus 14 of 63 “non-subset no. 4” cases (22.2%); the median survival was not yet reached for subset no. 4 versus 214 months for “non-subset no. 4” IGHV4-34 cases.

Comparisons of CLL HCDR3 sequences to sequences from public databases

Applying homology criteria described in “Patients and methods,” 193 IGHV-D-J public sequences were identified as similar to 1 of 48 “CLL-biased” subsets reported here (Table S6). This group comprised 148 CLL sequences, of which 80 were available on IMGT/LIGM-DB; therefore, the overall frequency of stereotyped HCDR3 cases among LIGM-DB CLL sequences was 17.3% (80 of 462 sequences).

The 45 non-CLL sequences homologous to 1 of the 48 “CLL-biased” subsets in our series (Table S6) comprised 28 clones from normal B cells (including 3 CD5+ B cells and 16 clones from preterm neonates prematurely exposed to environmental antigens), 9 autoreactive clones, 6 clones from immune dysregulation, and 2 splenic lymphoma clones. Therefore, when we considered all the 6892 sequences retrieved from public databases (Table 1), the chance of belonging to a “CLL-biased” subset was 0.7% overall (45 of 6430 sequences) and, in particular, 0.7% (28 of 4066) for normal sequences, 0.7% (9 of 1275) for autoreactive sequences, 1% (6 of 589) for sequences from “immune dysregulation” conditions, and 0.5% (2 of 500) for sequences from non-CLL malignancies.

Evidence for antigen receptor specificity for selected subsets

Applying homology criteria described in “Patients and methods,” HCDR3 homology to rheumatoid factors was identified in 4 subsets of our series (nos. 5, 7, 12, 13; Table S6). In particular, subset no. 13 comprises 3 mutated IGHV4-59–expressing cases closely homologous to a mutated rheumatoid factor from a healthy donor immunized with mismatched red blood cells (U8523456 ). Interestingly, these HCDR3s are also remarkably similar to the sequence carried by a hepatitis C virus–infected male patient with IGHV4-59–expressing CLL/SLL developing in a setting of type 2 cryoglobulinemia (AF30391757 ). In vitro rheumatoid factor reactivity has been previously evidenced for 2 further cases of our series, belonging to subsets no. 1 (FRA-293/POR) and no. 3 (FRA-009/AIG).58

Subset no. 6 cases are homologous to a CLL case (U84193) with poly-reactivity toward different autoantigens, including IgG.59 Furthermore, subset no. 6 cases demonstrate considerable HCDR3 homology with an anticardiolipin antibody (AF46096560 ).

In all, 64 of 916 CLL cases belonging to 7 different subsets (nos. 1, 3, 5-7, 12, 13) displayed HCDR3 homology with various autoreactive clones or 1 of 3 CLL cases for which reactivity with autoantigens has been reported.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed and compared IGHV genes in 916 CLL patients from France, Greece, Italy, and Spain. Our analysis confirms and extends previous findings on IGHV repertoire in CLL.21,25 Ten genes accounted for 62% of all cases; comparison of CLL sequences of our series to normal or autoreactive clones confirmed the skewed nature of CLL IGHV repertoire (Table S7). Importantly, this larger study confirms our previous report on the low frequency of the IGHV3-21 gene in CLL patients of Mediterranean origin25 ; IGHV3-21 ranked only ninth overall (3.45% of cases) and fifth among unmutated cases. This frequency is at least 3 times lower than the frequency reported in cases from Northern Europe.28,52-55 It would not be unreasonable to speculate that these differences in the frequency of IGHV3-21 in CLL patients of different geographic origins may reflect differences in genetic background, depending on variations in germline composition of the IGHV locus.61 Alternatively, they may be the effect of a potential environmental variable less frequently encountered in different regions.

In addition to IGHV and IGK/LV usage bias,21-26 the CLL immunoglobulin repertoire is characterized by the existence of subsets of cases with “stereotyped” HCDR3.25-33 By analyzing and comparing HCDR3 sequences in our large CLL cohort, we identified 48 different subsets of sequences with stereotyped HCDR3, collectively adding up to 201 cases. Therefore, each CLL patient in our cohort had more than a 1-in-5 chance (201 of 916; 21.9%) of carrying a stereotyped HCDR3. Inter-CLL homology was even more striking in the IGHV-unmutated group, with 35.6% of cases (140 of 393) belonging to a subset. Twenty-six of 48 subsets comprised 3 to 42 cases each and, in keeping with previous studies,32 were defined as “confirmed.” The remainder (22 of 48) comprised only pairs of sequences and, therefore, might be considered as “potential” because the possibility that their similarity may occur for serendipity cannot be a priori excluded, although the probability of sharing stereotyped receptors is extremely low (10−12). Interestingly, public database CLL sequences were found to be members of 9 of 22 “potential” subsets; furthermore, for several pairs with available data, light chains were also homologous. Analyses of an even larger series of CLL IGHV sequences will be necessary to confirm the actual existence of the remaining 13 subsets.

The high frequency (21.9%) of stereotyped HCDR3 in our series is remarkable; of note, we detected a similar frequency (17%) in public database CLL sequences (although one has to keep in mind that the CLL sequence collection on IMGT/LIGM-DB may be biased). This percentage could actually be an underestimation of the extent of HCDR3 homology in CLL; differences in the amino acid sequences often concern amino acids of similar functional properties. Comparison of our CLL sequences to non-CLL public sequences from B cells of diverse sources revealed that HCDR3 restriction is “CLL-biased.” Only 45 of 6430 non-CLL clones (0.7%) were identified with HCDR3s homologous to one of the “CLL-biased” subsets reported here. Although homologous sequences were also identified in the non-CLL data set, they derived from different sources; in such cases, homology could reflect random chance. HCDR3 restriction was recently shown to be infrequent in other B-cell lymphomas; furthermore, most homologous lymphomas expressed HCDR3s that resembled those of normal B cells, suggesting that they may arise randomly out of the pool of cells selected for non–self-antigens.33

The similarities among immunoglobulins from different CLL patients were underscored when we analyzed the association between heavy and light chains. Although there is no evidence in the normal immunoglobulin repertoire for preferential pairings of immunoglobulin heavy/light chain genes,62,63 in our CLL series certain HCDR3/K(L)CDR3 associations were represented at a remarkably high frequency. Specifically, more than 2% of cases (20 of 916) belonged to subset no. 1 (IGHV1-IGHV5 genes/IGHD6-19/IGHJ4 associated with IGKV1-39/1D-39). Other BCRs represented at a frequency more than 1% included IGHV3-21/IGLV3-21 (subset no. 2) and IGHV4-34/IGKV2-30 (subset no. 4). Considering the extremely low probability (10−12) of coexpression of identical BCRs,31 our findings further support the notion that a limited number of antigens are involved in selection of particular BCRs in CLL.22-24

In the present series, the chance of carrying a stereotyped HCDR3 was significantly lower for CLL cases expressing IGHV3 subgroup genes. These genes are characterized by their unique property to bind certain superantigens (eg, staphylococcal protein A) via subgroup-specific residues, most of which reside outside the conventional antigen-binding site.64,65 In this context, the low frequency of stereotyped HCDR3 sequences among CLL cases expressing IGHV3 genes might perhaps be viewed as indicative, at least for some cases, of selection by superantigens through non-HCDR3–based recognition. Alternatively, this observation might be accounted for by the high load of somatic mutations in many IGHV3 genes in CLL, which might make recognition of similarity in the original rearrangements difficult. In this context, 292 (68.4%) of 427 sequences from our series expressing IGHV3 genes had less than 98% homology to germline.

The possibility that malignant cells may recognize individual, discrete antigens or classes of structurally similar epitopes may be hypothesized even in those cases with a stereotyped HCDR3 using different IGHV genes or associating with different light chains. This is supported by at least 2 lines of evidence. (1) Both heavy- and light-chain CDR1/CDR2 loops adopt a small number of main chain conformations.66 Even when these loops have different lengths (as in several “stereotyped HCDR3” cases of our series using different IGHV genes), the extra residues may form a bump that does not affect significantly the overall loop conformation.66 (2) Several studies have suggested that the VH domain often plays a more important role than VL in the recognition mechanism of the immunoglobulin. Heavy-chain dominance in antigen binding by many anti-DNA antibodies has been documented extensively.67,68 Therefore, in the case of subsets of CLL patients with homologous heavy chains but different light chains, one might speculate that the BCRs could bind to the same epitope (recognized solely or mainly by the heavy chain).69-71

HCDR3 homology among CLL cases strongly suggests recognition of a putative common antigen. Although, it is not possible to accurately predict immunoglobulin specificity by sequence analysis alone, useful hints may derive from analysis of the known specificity of similar antibodies. Overall, 64 CLL cases belonging to 7 subsets displayed HCDR3 homology with various autoreactive clones or one of 3 CLL cases with reported reactivity against autoantigens.58,59 In addition, recombinant antibodies from CLL patients similar to the antibodies expressed by cases in subset nos. 1 to 6 of our series were recently shown to be auto(poly)reactive.72

CLL cells differ significantly in the capacity to signal through the BCR, with unmutated cases usually carrying more competent BCRs.73,74 Persistent antigenic stimulation could contribute to CLL survival and growth via surface immunoglobulin-mediated signals. In contrast, the favorable outcome of cases with mutated BCRs could derive from unresponsiveness to signaling due to receptor desensitization following chronic stimulation, perhaps by a ubiquitous self antigen.75,76 Although the nature of antigen involved in mediating the proposed desensitized state is unclear, the biased usage of the IGHV4-34 gene in the mutated subset might point to either a microbial antigen or an autoantigen.74 In this context, a less malignant behavior might be associated with an anergic state, perhaps suggesting that unmutated cases with more competent BCRs are better able to receive signals for survival or proliferation.23,73,74 Along this line of reasoning, cases with mutated stereotyped IGHV4-34/IGKV2-30 BCR (subset no. 4 of the present series) were found to experience an indolent course of the disease. The IGHV4-34 gene encodes antibodies that are intrinsically autoreactive by virtue of universal, and largely light chain-independent, recognition of the N-acetyllactosamine (NAL) antigenic determinant of the I/i blood group antigen; at least a subset of IGHV4-34 antibodies may also bind DNA.77,78 IGHV4-34 antibodies are infrequent in the sera of healthy individuals, although the IGHV4-34 gene is very frequent in the repertoire of peripheral B cells,77,78 suggesting an anergic status of these cells.

The analysis of the HCDR3s of the IGHV4-34–expressing cases of subset no. 4 might provide hints on the nature of the selecting (though anergizing) antigen. These cases carried long, positively charged HCDR3s, enriched in aromatic and positively charged amino acids that are usually associated with anti-DNA reactivity.79-85 Anti-DNA is the most common self-specificity in autoreactivity, perhaps due to the fact that DNA binding may be accomplished merely through surface-active basic amino acids, especially arginine.86 Arginine-arginine (RR) or lysine-arginine (KR) dipeptides were found in all IGHD-J junctions of subset no. 4, leading to creation of a R(K)RYYY motif at the tip of HCDR3. As revealed by alignment to public database sequences, this feature is “CLL-biased.”

The high probability that anti-DNA antibodies arise during the formation of the preimmune repertoire and during clonal selection increases the risk of anti-DNA autoimmunity. Nevertheless, anti-DNA B cells are efficiently regulated, even in anti-DNA transgenic mice.68 In such mice, just a few strategically positioned aspartic acid residues within a subset of κ light chains were found to be adequate for editing most anti-DNAs.68 In this context, it is perhaps relevant that subset no. 4 is characterized by the high frequency of somatically introduced aspartic acid residues both in the VH and the VK regions (Figure 4).

The impact of IGHV mutational status on the clinical behavior of CLL makes this prognostic marker important for therapeutic decisions. However, based on the results presented here, additional molecular features of the BCR expressed by CLL malignant cells should also be considered. For instance, the IGHV3-21/IGLV3-21 subset (no. 2) should be regarded as unfavorable whatever the degree of mutation.25,28,52-55 Conversely, although unmutated, like the majority of IGHV1-69 cases, patients with CLL expressing IGHV1-69/IGHD3-10/IGHJ6 sequences with stereotyped HCDR3 (subset no. 5) seem to follow a strikingly indolent course (Figure 7). Additional subsets with a specific disease evolution profile may be evidenced in the future.

In conclusion, CDR3 restriction is a remarkable feature of the CLL immunoglobulin repertoire. The unique, “CLL-biased” molecular features of stereotyped HCDR3 sequences along with biased somatic hypermutation patterns (for selected BCRs) supports the notion that CLL development and evolution is not a simple stochastic event and indicates a role for antigen in driving the cell of origin for at least a proportion of CLL cases. The striking association between stereotyped BCRs and clinical/phenotypic features or outcome for selected subsets of CLL patients suggests that a particular antigen-binding site can be critical in determining clinical presentation and possibly also prognosis. It would not be unreasonable to speculate that stimulation through the BCR may occur at different time points in the natural history of the disease, depending on the nature of the antigenic elements. Considering the clinical-biologic associations with certain subsets, it is conceivable that future therapeutic decisions should be based not only on mutational status of IGHV genes but also on individual HCDR3 characteristics.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Contribution: P.G. and F.D. contributed equally to this work as last authors in designing the research, interpreting the data, and drafting the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Milano, PRIN-MIUR, the CLL Global Research Foundation, the Fondazione Anna Villa e Felice Rusconi ONLUS, Varese, the French Ministry of Health and Redes Temáticas de investigación cooperativa V-2003-REDC10E-O, V-2003-REDC10P-O, and Redes Temáticas de Cáncer GO3/008. C.M. holds a contract from the Spanish Ministerio de Sanidad (CM-04/00187).

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal