We demonstrated a novel strategy for specific and persistent inhibition of antibody (Ab) production against blood group A or B carbohydrate determinants necessary for successful ABO-incompatible transplantation. Similar to human blood group O or B individuals, mice have naturally occurring Abs against human blood group A carbohydrates in their sera. B cells with receptors for A carbohydrates in mice belonging to the CD5+CD11b+B-1a subset have phenotypic properties similar to those of human B cells. These cells could be temporarily eliminated by injecting synthetic A carbohydrates (GalNAcα1–3, Fucα1–2Gal) conjugated to bovine serum albumin (A-BSA) and anti-BSA Abs. In mice that received the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs, the serum levels of anti-A IgM were reduced, but immunization with human A erythrocytes resulted in increased serum levels of anti-A Abs. When combined with cyclosporin A (CsA) treatment, which blocks B-1a cell differentiation, and treatment with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs, the serum levels of anti-A Abs were persistently undetectable in the mice even after the immunization. B cells with receptors for A carbohydrates were markedly reduced in these mice. These results are consistent with the hypotheses that treatment with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs temporarily depletes B cells responding to A determinants, and CsA treatment prevents the replenishment of these cells.

Introduction

The use of ABO-incompatible donor organs is a possible solution for the shortage of donor organs for transplantation; however, naturally occurring Abs against blood group A or B (A/B) carbohydrate determinants in sera are a major impediment to achieving successful transplantation. Transplantation across ABO blood barriers using living donor organs has been performed with some success.1,2 Removing anti-A/B antibodies (Abs) by plasma exchange or plasmapheresis, splenectomy, and use of anti–B-cell immunosuppressants in the recipients are widely adopted strategies to avoid Ab-dependent rejection of ABO-incompatible organ grafts.3,,,,–8 Despite the use of such therapeutic methods, graft survival in ABO-incompatible organ transplantation is generally inferior compared with that in ABO-compatible transplantation because of the reappearance of anti-A/B Abs.1,4,9,,–12 The specific and persistent inhibition of anti-A/B Ab production might be necessary for completely preventing anti-A/B Ab-mediated rejection; however, a method for either elimination or suppression of B-cell clones responding to the A/B carbohydrates has not yet been established.

Using surface staining with fluorescein-labeled synthetic A carbohydrates conjugated to bovine serum albumin (BSA), we previously demonstrated that B cells with surface immunglobulin M (sIgM) receptors for blood group A carbohydrate determinants are found exclusively in a small but nevertheless significant B-cell subpopulation (ie, sIgM+ CD11b+ CD5+ B-1 cells) in blood group O or B human peripheral blood.13 Anti-A–specific human Abs were detected in the sera of nonobese diabetic–severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice that received blood group O human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) containing B cells with anti-A receptors. In contrast, these Abs were not detected in sera from NOD/SCID mice that received blood group A human PBMCs devoid of such B cells. This suggests that the B-1 cells with anti-A receptors comprise cells actively producing anti-A Abs and/or precursors of such cells. CD11b+ CD5+ B-1 cells differ from the more abundant conventional CD11b− CD5− B-2 cells in many aspects that presumably reflect their different roles in the immune system. In addition to their differences in the cell-surface phenotypes, both these cells possess characteristics that suggest that they are antigen (Ag) specific. Previous reports indicated that B-1 cell differentiation occurs through Ig gene rearrangement following stimulation with certain Ags, particularly thymus-independent type 2 (TI-2) Ags.14,,–17 Furthermore, cyclosporin A (CsA), which is widely and satisfactorily used to prevent T-cell–mediated rejection of allografts, is reported to block such differentiation.18 However, anti-A/B Ab levels are known to rapidly increase in the sera of patients receiving an ABO-incompatible organ, even on CsA therapy. This discrepancy may be explained by the possibility that CsA has no effect on cells that are actively producing Abs, or on cells that have already differentiated to B-1 cells. In this case, the specific elimination of both Ab-producing cells and differentiated B-1 cells with anti-A/B specificity as well as subsequent CsA therapy might lead to lasting inhibition of anti-A/B Ab production following ABO-incompatible organ transplantation. Since we previously reported that both Ab (IgM)–producing cells and B-1 cells express sIgM B-cell receptors (BCRs), which can bind specific Ags,19 these cells with anti-A/B receptors may be targeted for specific elimination by using synthetic A/B carbohydrates conjugated with a cytotoxic constituent. The administration of these carbohydrates into the circulation may result in their specific binding to the corresponding BCRs, consequently depleting these B cells via their interaction with the cytotoxic constituent without affecting B-cell clones with other Ab specificities.

The present study has proved that normal mice have B cells with anti-A receptors, which show the sIgM+ CD11b+ CD5+ B-1 phenotype, and naturally occurring Abs against human blood group A carbohydrates are detectable in their sera, resembling human blood group O or B individuals. We therefore used such mice for investigating the effects of a novel approach consisting of treatment with synthetic A carbohydrates and CsA on B cells responding to blood group A Ags.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female Balb/c mice, aged 12 weeks, were purchased from Clea Japan (Osaka, Japan) and housed in the animal facility of Hiroshima University in a specific pathogen–free microisolator environment. The animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hiroshima University and conducted in accord with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985).

In vivo immunization

Fresh human peripheral blood collected from blood group A volunteers was irradiated at 30 Gy to deplete white blood cells (WBCs). Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki from all volunteers. A suspension of 5 × 108 human blood group A red blood cells (A-RBCs) in 1 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected into the peritoneal cavity of each mouse.

Flow cytometry analysis for detecting B cells with receptors for blood group A carbohydrate determinants

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from homogenized spleen (Spl) of mice using erythrocyte-lysing solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 1 mM EDTA-2Na, and PBS [pH 7.4]). Peritoneal cavity (PerC) cells were isolated by peritoneal lavage using cold PBS. To detect B cells with receptors for human blood group A trisaccharide, 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (FLUOS)–conjugated A-BSA (GalNAcα1,3Fucα1,2Galβ-O-(CH2)8CONH(CH2)2NHCO(CH2)5CO)n-NH-BSA (molecular weight of glycoconjugate = 82 563 kDa, average sugar residues per protein molecule = 19; Dextra, Reading, United Kingdom), and control FLUOS-conjugated BSA (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) were used. Fluorescein conjugation of A-BSA and BSA was performed using Fluorescein Protein Labeling kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. 106 Spl or PerC cells per 100 μL were incubated with 0.5 μg/100μL FLUOS-A-BSA or control FLUOS-BSA in a flow cytometry (FCM) medium (PBS containing 0.1% BSA and 0.1% sodium azide) for 1 hour at 4°C. The cells were further stained with biotin-conjugated anti-mouse IgM R6-60.2 (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA), phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti-mouse CD11b M1/70 (BD PharMingen), anti-mouse CD19 1D3 (BD PharMingen), or anti-mouse CD5 53-7.3 (BD PharMingen) mAb to classify B-cell subsets. The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. Four-color FCM was performed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). Nonspecific Fc γreceptor binding of labeled Abs was blocked by anti-mouse CD16/32 2.4G2 (BD PharMingen). An isotype-matched irrelevant mAbs were used as a control. Dead cells were excluded from the analysis based on light scatter and staining with propidium iodide.

ELISA assays

Total mouse Igs and anti-A–specific Abs (including IgG and IgM) levels in sera were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously.13,20 Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 5 μg/mL of goat anti-mouse Ig (IgG+IgM+IgA, heavy chain + light chain; Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL), 5 μg/mL synthetic A-BSA (Dextra) or control BSA (Roche). Diluted serum samples were incubated in the plates, and bound Abs were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG/IgM-specific Abs (KPL, Guilford, United Kingdom). Color development was achieved using 0.1 mg/mL O-phenylenediamine (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in a substrate buffer. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 3 M H2SO4, and absorbance was measured at 492 nm. Anti-A–specific Ab levels were determined by subtracting the absorbance of wells coated with control BSA from the absorbance of wells coated with A-BSA. Purified mouse IgG (Zymed, South San Francisco, CA) and IgM (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Aurora, OH) were used as standard controls.

FCM analysis of anti-human RBC Abs

Indirect immunofluorescence staining of A-RBCs and human blood group O RBCs (O-RBCs) was used to detect anti-RBC Abs. A total of 106 RBCs were incubated with 100 μL of serially diluted mouse serum, washed, and incubated with PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgM mAbs (BD PharMingen). The ratio of the median fluorescence intensity of staining of A-RBCs to that of O-RBCs represents the anti-A–specific Ab level.

ELISPOT for detecting anti-A Ab-producing cells

Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay to detect anti-A Ab-producing cells was performed as described previously.21 Briefly, nitrocellulose membranes of a 96-well filtration plate (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated with 5 μg/mL A-BSA or control BSA for detecting anti-A IgM/IgG-producing cells. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked using 0.4% BSA in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM; Sigma). Serial dilutions of cell suspension in IMDM supplemented with 0.4% BSA, 5 μg/mL insulin (Sigma), 5 μg/mL transferrin (Sigma), 5 ng/mL sodium selenite (Sigma), 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 1 μg/mL gentamicin were added to triplicate wells. After 24 hours of culture at 37°C, bound Abs were detected using horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse IgM/IgG Abs (Southern Biotechnology), followed by color development with 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (Sigma). After the membranes were dried the wells of 96-well filtration plates for ELISPOT assay were observed using a Leica MZ6 microscope (Leica, Wetzler, Germany; magnification 10×/0.63), and the photos of those wells were taken by a Nikon COOL PIX 950 digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). The photo data were visualized using Abode Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

In vitro B-cell proliferation assay

The resting B cells were isolated from splenocytes of untreated Balb/c mice by negative selection using a B-cell isolation kit and auto–magnetic-associated cell sorter (MACS) (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then, the B cells were labeled with 5 μM 5-(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as described previously.22 The CFSE-labeled cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Sanko, Tokyo, Japan), 5 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Katayama, Osaka, Japan), 1% HEPES buffer (GIBCO, Grand Island, NY), and 100 IU/mL penicillin–100 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO). The following stimuli were added at the start of the culture: 10 μg/mL of goat anti-mouse IgM F(ab′)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), 1 μg/mL recombinant mouse CD40L, and 1 μg/mL enhancer (Alexis Cor, Lausen, Switzerland), as well as 0.02 μg/mL recombinant mouse IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). In the CsA inhibition assay, various doses of CsA (6.25-100 ng/mL; which was kindly provided by Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) were added at the start of the culture. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 for 3 days. The cultivated cells were stained with PE-conjugated CD19 1D3 (BD PharMingen) or biotinylated CD5 53-7.3 mAb (BD PharMingen). The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin.

In vitro depletion of anti-A Ab producing cells by using A-BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and complement

Spl cells (10 × 107/mL) from Balb/c mice that had received an intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 A-RBCs (8 days prior to analysis) were cultured in IMDM supplemented with 0.4% BSA in the presence of various concentrations of A-BSA (6.125-200μg/mL) for 30 minutes, then incubated with 50-fold diluted rabbit anti-BSA Abs (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Aurora, Ohio) for 30 minutes, followed by incubation with 25-fold diluted rabbit complement (Cedarlane, Burlington, ON) for 15 minutes. Finally, all cells were subjected to ELISPOT assay to determine the frequency of anti-A IgM-producing cells.

In vivo treatment using A-BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and/or CsA

Balb/c mice received an intraperitoneal injection of A-BSA diluted in PBS at a dose of 200 μg/mouse. After 6 hours, the mice received an intraperitoneal injection of rabbit anti-BSA Abs that had been diluted 20-fold in PBS at a dose of 1 mL/mouse. As indicated, CsA was daily administered intraperitoneally at various doses (5-50 mg/kg/day). Untreated mice and mice receiving injections of either A-BSA or CsA alone were used as controls.

Statistical analysis

The results were statistically analyzed using the unpaired Student t test of means or analysis of variance (ANOVA). A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Normal mice possess B cells with receptors for blood group A determinants, which show sIgMhigh CD11b+ CD5+ B-1 phenotype in the peritoneal cavity, and IgM+ CD11b− CD5− B-2 phenotype in the spleen

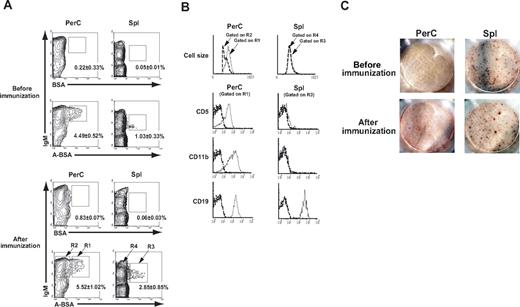

ABO histo-blood group Abs are thought to be developed following trisaccharide-specific immune stimulation by environmental bacteria that express these carbohydrate determinants.23,,–26 Consistent with the accepted belief that the response of the B-cell compartment to microbial products is derived preferentially from the activation of CD5+ B-1 cells,27,–29 we recently demonstrated that B cells with receptors for blood group A carbohydrate determinants were found exclusively in a sIgM+ CD11b+ CD5+ B-1 subpopulation in blood group O or B human peripheral blood.13 Previous experiments by us and other researchers showed significant levels of naturally occurring anti-human blood group A–determinant Abs but undetectable levels of anti-human blood group B–determinant Abs in the sera from several strains of mice.13,23,30,31 The absence of anti-B Abs might be explained by the presence of B-like structures, probably Galα1–3Galβ1–4GlcNAc (Gal) carbohydrate residues, on mouse cells, thereby retaining B-cell tolerance toward B determinants.32 We attempted to identify B cells with sIgM that binds to A carbohydrate determinants in Balb/c mice that were either untreated or immunized with A-RBCs. Cells from the Spl and PerC where B-1 cells are predominantly located were stained with FLUOS-labeled synthetic A-BSA together with anti sIgM mAbs and subjected to FCM analysis. The cells with sIgM that bound to A-BSA (A-BSA–binding B cells) were detected in the Spl and PerC of untreated mice (Figure 1A). In contrast, BSA-binding B cells were not detected Spl or PerC, indicating the specificity of the A-determinant ligand for corresponding sIgM on B cells. After single immunization with A-RBCs, a statistically significant increase was observed in the population of A-BSA–binding B cells in the Spl; however, the increase in the population of these cells in the PerC did not reach a significant level. The frequency of A-BSA–binding B cells in PerC was significantly higher than that in Spl. To further characterize the phenotype of B cells with A-binding sIgM, A-BSA–binding B cells were selected by gating, and were evaluated for the expression of various surface markers by 3-color FCM analysis. A-BSA–binding B cells in the PerC were IgMhigh, CD19+, CD11b+, and CD5+, which is phenotypically consistent with the properties of the B-1a subpopulation. In contrast, A-BSA–binding B cells in the Spl were IgM+, CD19+, CD11b−, and CD5−, which is phenotypically indistinguishable from conventional B-2 cells (Figure 1B).

Phenotypic and functional properties of B cells with receptors for blood group A carbohydrate determinants in mice. PerC and Spl cells were prepared from Balb/c mice that were either untreated or immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs. The assay was performed after 7 days after the immunization. The cells were stained with FLUOS-BSA–synthetic A determinant (GalNAcα1–3Fucα1–2Gal; A-BSA) or control FLUOS-conjugated BSA and biotinylated anti-mouse IgM mAb along with various PE-conjugated mAbs (CD5, CD19, or CD11b). The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. To ensure statistical significance, date on 105 PerC cells and 2 × 105 Spl cells were collected for each sample. (A) Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis show increased A-BSA–binding B cells in the Spl and PerC. Percentages given are of Spl or PerC cells in each region (average values ± SD). (B) Carbohydrate determinant-binding sIgM+ B cells were selected by gating and analyzed for the expression of various B cell markers. Dotted lines represent negative control staining with isotype-matched Abs. The results were consistent in 4 independent experiments. (C) Anti-A IgM-producing cells were detected by the ELISPOT assay. Spl, BM, PerC, cervical lymph node cells, and mesenteric lymph node cells were prepared from Balb/c mice that were either untreated or immunized with A-RBCs. A representative image of wells with 8 × 105 seeded cells is shown. The results are representative of 5 mice in each group. Anti–A carbohydrate determinant IgM-producing cells are localized mainly in the Spl.

Phenotypic and functional properties of B cells with receptors for blood group A carbohydrate determinants in mice. PerC and Spl cells were prepared from Balb/c mice that were either untreated or immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs. The assay was performed after 7 days after the immunization. The cells were stained with FLUOS-BSA–synthetic A determinant (GalNAcα1–3Fucα1–2Gal; A-BSA) or control FLUOS-conjugated BSA and biotinylated anti-mouse IgM mAb along with various PE-conjugated mAbs (CD5, CD19, or CD11b). The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. To ensure statistical significance, date on 105 PerC cells and 2 × 105 Spl cells were collected for each sample. (A) Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis show increased A-BSA–binding B cells in the Spl and PerC. Percentages given are of Spl or PerC cells in each region (average values ± SD). (B) Carbohydrate determinant-binding sIgM+ B cells were selected by gating and analyzed for the expression of various B cell markers. Dotted lines represent negative control staining with isotype-matched Abs. The results were consistent in 4 independent experiments. (C) Anti-A IgM-producing cells were detected by the ELISPOT assay. Spl, BM, PerC, cervical lymph node cells, and mesenteric lymph node cells were prepared from Balb/c mice that were either untreated or immunized with A-RBCs. A representative image of wells with 8 × 105 seeded cells is shown. The results are representative of 5 mice in each group. Anti–A carbohydrate determinant IgM-producing cells are localized mainly in the Spl.

Anti-A Ab-producing cells are localized predominantly in the spleen

Next, we determined the anatomical location of the cells that actively produce anti-A Abs. In mice that were either nonimmunized or immunized with an intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 A-RBCs, the frequency of anti-A Ab-producing cells was quantified 7 days after the immunization by ELISPOT assay of the suspended cells from various tissues including Spl, bone marrow (BM), PerC, cervical lymph nodes, and mesenteric lymph nodes. Anti-A IgM-producing cells were localized mainly in the Spl, and were detectable in the BM, but not in the PerC (Figure 1C), cervical lymph nodes, and mesenteric lymph nodes (data not shown). After immunization with A-RBCs, red spots formed due to Ab production increased both in number and size in the Spl, indicating the enhanced frequency and activity of anti-A IgM-producing cells at this site (Figure 1C). No anti-A IgG-producing cells were detected at any tested sites, even after A-RBC immunization at this time point (data not shown).

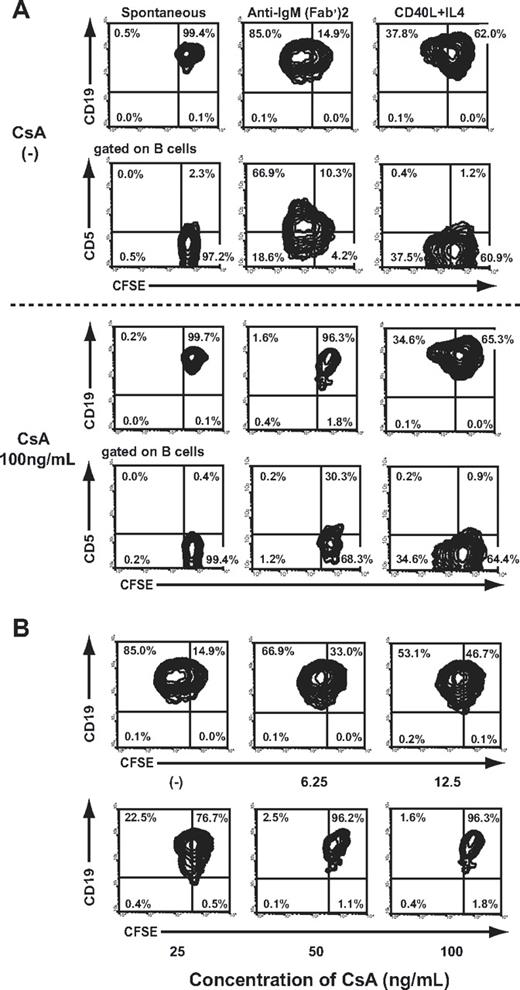

CsA blocked CD5+ B-1 cell differentiation induced by sIgM cross-linking but not B-2 cell differentiation by CD40 ligation

It has been recently demonstrated that PerC B-1 cells are precursors of splenic IgM Ab-producing cells,33 and the PerC B-1 cells are differentiated through Ig gene rearrangement following stimulation with TI-2 Ags.14,,–17 A previous report supports the claim that such B-1 cell differentiation can be blocked by CsA treatment.18 To verify this hypothesis, resting B cells isolated from splenocytes of Balb/c mice were treated with anti-IgM F(ab′)2, an analog of TI-2 Ags, or CD40L and IL-4, which provide thymus-dependent inductive signals in the presence or absence of CsA in vitro. Prior to these treatments, resting B cells were labeled with CFSE, thereby allowing phenotypic analysis of the proliferating cells by multicolor FCM analysis. CD19+ B cells stimulated with anti-IgM F(ab′)2 or with CD40L/IL-4 vigorously proliferated after 3 days in culture; however, only the former developed into CD5+ B cells. Proliferating B cells induced by CD40L/IL-4 lacked CD5 expression. The limited proportion of nonstimulated/nonproliferating spontaneous B cells that express CD5 might be the cells that have already differentiated to B-1 cells prior to the culture. CsA added at the start of culture inhibited B-cell proliferation induced by anti-IgM F(ab′)2; however, it had no effect on CD40L/IL-4 induced B-cell proliferation (Figure 2A). A clinically relevant concentration of CsA (100 ng/mL) completely blocked CD5+ B-cell proliferation (Figure 2B). In the PerC of mice treated with CsA for 2 weeks, the proportion of IgMhigh CD11b+ CD5+ B-1a cells exclusively decreased in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibitory effect of CsA on B-1a cells was obvious even at a clinically relevant dose (5-50 mg/kg/day; Table 1). The total number of PerC B cells obtained from a mouse was constant regardless of CsA doses (ranging from 5 × 106/mouse to 8 × 106/mouse), and the proportion of sIgM+ CD5− CD11b− B-2 cells was conversely elevated. These findings are consistent with the results of the in vitro study demonstrating that CsA blocks the differentiation from B-2 cells to B-1a cells but does not affect B-2 cells per se, although we cannot exclude the possibility that CsA treatment influences the migration of certain subsets of B cells from/to the PerC.

CsA blocked CD5+ B-1 cell differentiation induced by cross-linking sIgM but not B-2 cell differentiation by CD40 ligation. The CFSE-labeled resting B cells from the untreated control mice were cultured in the presence of either soluble F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-IgM as an analog of TI-2 Ags or CD40L and IL-4 that provide thymus-dependent inductive signals for 3 days. CsA was added to the culture medium at various doses. The cultivated cells were stained with PE-conjugated CD19 or biotinylated CD5 mAb. The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. (A) Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis are shown. The percentages of the total number of cultivated cells in each quadrant are shown. (B) The relationship between the concentration of CsA and its inhibitory effect on B-1a cell differentiation induced by anti-IgM F(ab′)2 fragments. The percentages of the total number of cultivated cells in each quadrant are shown.

CsA blocked CD5+ B-1 cell differentiation induced by cross-linking sIgM but not B-2 cell differentiation by CD40 ligation. The CFSE-labeled resting B cells from the untreated control mice were cultured in the presence of either soluble F(ab′)2 fragments of anti-IgM as an analog of TI-2 Ags or CD40L and IL-4 that provide thymus-dependent inductive signals for 3 days. CsA was added to the culture medium at various doses. The cultivated cells were stained with PE-conjugated CD19 or biotinylated CD5 mAb. The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. (A) Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis are shown. The percentages of the total number of cultivated cells in each quadrant are shown. (B) The relationship between the concentration of CsA and its inhibitory effect on B-1a cell differentiation induced by anti-IgM F(ab′)2 fragments. The percentages of the total number of cultivated cells in each quadrant are shown.

PerC B cells in mice that received CsA treatment

| Groups . | No. . | Cells/mouse, × 106 . | Lymphocytes, % total cells . | B cells, % lymphocytes . | B-1a cells, % B cells . | B-1b cells, % B cells . | B-2 cells, % B cells . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5 | 10.8 ± 1.1 | 89.7 ± 1.6 | 83.8 ± 3.7 | 64.0 ± 4.4 | 16.7 ± 2.1 | 15.7 ± 3.4 |

| 5 mg/kg | 3 | 14.5 ± 5.0 | 69.2 ± 0.7 | 61.8 ± 0.8 | 33.7 ± 1.1 | 12.6 ± 0.6 | 47.5 ± 5.9 |

| 10 mg/kg | 5 | 15.7 ± 2.4 | 68.6 ± 2.0 | 66.4 ± 4.3 | 19.6 ± 2.2 | 13.6 ± 2.9 | 66.9 ± 3.8 |

| 50 mg/kg | 5 | 14.3 ± 3.0 | 53.9 ± 9.1 | 57.3 ± 6.9 | 22.3 ± 3.5 | 13.7 ± 1.6 | 61.3 ± 3.9 |

| Groups . | No. . | Cells/mouse, × 106 . | Lymphocytes, % total cells . | B cells, % lymphocytes . | B-1a cells, % B cells . | B-1b cells, % B cells . | B-2 cells, % B cells . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5 | 10.8 ± 1.1 | 89.7 ± 1.6 | 83.8 ± 3.7 | 64.0 ± 4.4 | 16.7 ± 2.1 | 15.7 ± 3.4 |

| 5 mg/kg | 3 | 14.5 ± 5.0 | 69.2 ± 0.7 | 61.8 ± 0.8 | 33.7 ± 1.1 | 12.6 ± 0.6 | 47.5 ± 5.9 |

| 10 mg/kg | 5 | 15.7 ± 2.4 | 68.6 ± 2.0 | 66.4 ± 4.3 | 19.6 ± 2.2 | 13.6 ± 2.9 | 66.9 ± 3.8 |

| 50 mg/kg | 5 | 14.3 ± 3.0 | 53.9 ± 9.1 | 57.3 ± 6.9 | 22.3 ± 3.5 | 13.7 ± 1.6 | 61.3 ± 3.9 |

CD5+ B-1a cells exclusively decreased, but CD5− B-2 increased in the PerC of the mice treated with CsA. After 2 weeks daily intraperitoneal injection of various doses of CsA into Balb/c mice, peritoneal cavity cells were harvested and stained with mAbs against B220 (RA3-6B2), CD11b (M1/70), and CD5 (53-7.3) to determine B-cell subsets (B-1a, B220+CD11b+CD5+, B-1b, B220+CD11b+CD5−, B-2, and B220+CD11b−CD5−. B-1a cells have been well defined as CD19+ B220+ sIgM+ CD11b+ CD5+ cells. Since B220+ CD11b+ CD5+ cells universally expressed both sIgM and CD19, and sIgM+ CD11b+ CD5+ cells universally expressed both CD19 and B220 in our previous studies, we considered both B220+ CD11b+ CD5+ cells and sIgM+ CD11b+ CD5+ cells as B-1a cells. All mAbs were purchased from BD PharMingen). Mean percentages (± SEM) are shown.

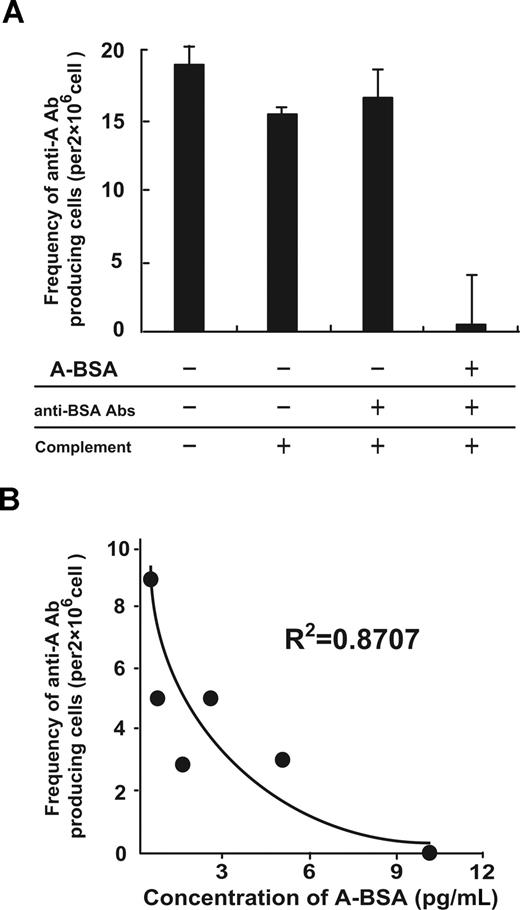

In vitro depletion of anti-A IgM-producing cells by A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs

The ability of A-BSA and rabbit anti-BSA Abs (A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs) to deplete anti-A IgM-producing cells was studied in vitro. Balb/c mice were twice immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs at a 1-week interval. Spl cells prepared from the mice 7 days after the second immunization were incubated with various concentrations of A-BSA, and then incubated with rabbit anti-BSA Abs, followed by incubation with rabbit complement. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to ELISPOT assay for determining the frequency of anti-A IgM-producing cells. Incubation of the Spl cells with 10 μg/mL of A-BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and complement almost completely eliminated anti-A IgM-producing cells, but no significant depletion of these cells was observed when the Spl cells were incubated with rabbit anti-BSA Abs and complement alone (Figure 3A). A linear relationship was observed between the frequency of the remaining anti-A IgM-producing cells after A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs treatment and the logarithmic concentration of the used (Figure 3B). These findings indicate that A-BSA binding to specific anti-A sIgM on the B cells followed by anti-BSA binding leads to complement activation, resulting in specific toxicity against these B cells.

In vitro depletion of anti–A carbohydrate determinant IgM-producing cells by A-BSA and anti-BSA Abs. (A) Balb/c mice were immunized twice with an intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 A-RBCs at a 1-week interval. At 8 days after the second immunization, the Spl cells from the immunized mice were incubated with various concentrations of A-BSA, as indicated. These cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-BSA Abs, followed by incubation with rabbit complement, as described in “In vitro depletion of anti-A Ab producing cells by using A-BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and complement.” Subsequently, the cells were subjected to ELISPOT assay to determine the frequency of anti-A IgM-producing cells. Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown. (B) The relationship between the frequency of the remaining anti-A IgM-producing cells and the A-BSA concentrations used is shown (R2 = .871). The frequency of anti-A Ab-producing cells shown was determined by subtracting the number of dots produced by the cells in the wells coated with control BSA from the number of dots produced by the cells in the wells coated with A-BSA.

In vitro depletion of anti–A carbohydrate determinant IgM-producing cells by A-BSA and anti-BSA Abs. (A) Balb/c mice were immunized twice with an intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 A-RBCs at a 1-week interval. At 8 days after the second immunization, the Spl cells from the immunized mice were incubated with various concentrations of A-BSA, as indicated. These cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-BSA Abs, followed by incubation with rabbit complement, as described in “In vitro depletion of anti-A Ab producing cells by using A-BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and complement.” Subsequently, the cells were subjected to ELISPOT assay to determine the frequency of anti-A IgM-producing cells. Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown. (B) The relationship between the frequency of the remaining anti-A IgM-producing cells and the A-BSA concentrations used is shown (R2 = .871). The frequency of anti-A Ab-producing cells shown was determined by subtracting the number of dots produced by the cells in the wells coated with control BSA from the number of dots produced by the cells in the wells coated with A-BSA.

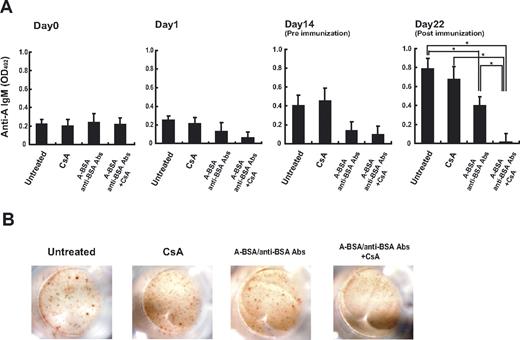

Persistent reduction of anti-A IgM levels in sera from mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA

The ability of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs to deplete anti-A IgM-producing cells was next studied in vivo. Balb/c mice were injected with A-BSA followed by rabbit anti-BSA Abs; however, these mice did not receive exogenous administration of complement because they are competent with regard to complement-mediated cytotoxicity. In mice that received the A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection, the anti-A IgM serum levels were reduced on day 1, and remained low until day 14 (Figure 4), whereas in untreated control mice, these levels gradually increased during the observation period. This is consistent with the age-related increase in mouse naturally occurring Abs as described previously.34 No reduction, but rather a slight increase in the anti-A IgM levels, was observed in mice that had received only the A-BSA injection, eliminating the possibility that the reduction in anti-A Abs observed in the mice treated with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs was merely due to adsorption by the corresponding carbohydrate epitopes of the injected A-BSA. Immunization with an intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 108 A-RBCs facilitated anti-A IgM production in the untreated control mice. A similar immunization at 2 weeks following A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab treatment also increased the anti-A Ab serum levels, although these levels were low compared with those of untreated control mice. This indicated that B cells responding to A-Ags persist in the mice. The presence of these B cells in mice at this time point might be due to replenishment by development of new Ab-producing cells from precursors. This may be because these B cells in mice were temporarily depleted by the A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab treatment, as indicated by the absence of both anti-A Ab-producing cells and B cells with anti-A receptors on the day after the treatment (data not shown). Based on the data presented in Figure 2, CsA might be able to inhibit such replenishment by blocking B-1 cell differentiation. Consistent with this assumption, when CsA treatment and A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab treatments were combined, the anti-A Ab serum levels at 3 weeks after A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection were completely undetectable by ELISA. In addition, anti-A Ab-producing cells were undetectable in the Spl even after immunization with A-RBCs (Figure 4). CsA treatment (10 mg/kg per day) alone neither reduced the anti-A Ab serum levels nor inhibited anti-A Ab production in response to immunization with A-RBCs; this finding suggests that CsA does not affect preexisting Ab-producing cells. The reduction of anti-A Ab levels in the sera of mice treated with a combination of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA was also confirmed by FCM analysis at 10 weeks after A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection. At this time point, the response to group A determinants was significantly reduced, but response to other human RBC antigens was preserved at normal levels in mice treated with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA. This indicates the specificity of our approach to the correspondent blood group antigens (Figure 5). In addition, the total serum IgM and IgG levels were maintained at normal levels in these mice (data not shown).

Persistent reduction in anti-A Ab levels in the sera of mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA. Balb/c mice received an intraperitoneal injection of A-BSA (100 μg/mouse). After 6 hours, rabbit anti-BSA Abs were injected into the mice. Furthermore, the mice received daily injection of CsA at dose of 10 mg/kg/day. Untreated mice and mice that received injections of either A-BSA or CsA alone were used as controls. At 14 days after injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab, the mice were intraperitoneally immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs. (A) The levels of anti-A IgM in the sera of these mice were determined by ELISA assay before and after treatment (0, 1, 14, and 22 days after A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection). Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown. The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 6; mice receiving CsA alone, n = 5; mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone, n = 5; and mice that received a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5. *P < .05. (B) Anti-A Ab-producing cells in the Spl of each mouse were detected by the ELISPOT assay (22 days after the A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection).

Persistent reduction in anti-A Ab levels in the sera of mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA. Balb/c mice received an intraperitoneal injection of A-BSA (100 μg/mouse). After 6 hours, rabbit anti-BSA Abs were injected into the mice. Furthermore, the mice received daily injection of CsA at dose of 10 mg/kg/day. Untreated mice and mice that received injections of either A-BSA or CsA alone were used as controls. At 14 days after injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab, the mice were intraperitoneally immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs. (A) The levels of anti-A IgM in the sera of these mice were determined by ELISA assay before and after treatment (0, 1, 14, and 22 days after A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection). Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown. The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 6; mice receiving CsA alone, n = 5; mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone, n = 5; and mice that received a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5. *P < .05. (B) Anti-A Ab-producing cells in the Spl of each mouse were detected by the ELISPOT assay (22 days after the A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection).

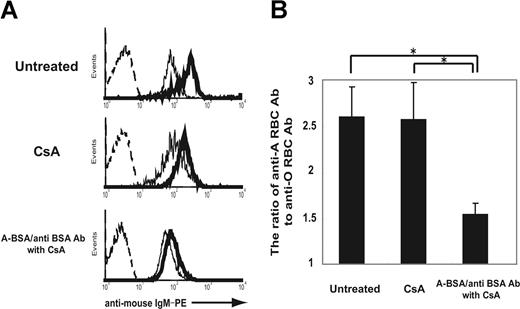

Reduced response to group A determinants and preserved normal response to other human RBC antigens in mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. Mice that were either untreated or treated with CsA alone or A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs along with CsA were intraperitoneally immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs 8 and 9 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs. At 8 days after the last immunization, the levels of anti-human RBC Ab (IgM) in the sera of these mice were determined by FCM analysis for evaluating the indirect immunofluorescence staining of human A-RBCs and O-RBCs (10 weeks after A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection). (A) Representative histograms obtained by FCM analysis show a reduced response to group A determinants and a preserved normal response to other human RBC antigens in mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. The dotted lines represent the negative control staining of human A-RBCs with secondary mAb alone (PE-conjugated rat anti–mouse IgM mAbs). Thin and solid lines represent staining of human O-RBCs and A-RBCs, respectively, with 20-fold–diluted mouse serum plus PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgM mAbs. (B) The ratio of the median fluorescence intensity of staining of A-RBCs to that of O-RBCs represents the anti-A determinant Ab level. Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown. The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 5; mice receiving CsA alone, n = 4; mice receiving a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5. *P < .05.

Reduced response to group A determinants and preserved normal response to other human RBC antigens in mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. Mice that were either untreated or treated with CsA alone or A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs along with CsA were intraperitoneally immunized with 5 × 108 A-RBCs 8 and 9 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs. At 8 days after the last immunization, the levels of anti-human RBC Ab (IgM) in the sera of these mice were determined by FCM analysis for evaluating the indirect immunofluorescence staining of human A-RBCs and O-RBCs (10 weeks after A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab injection). (A) Representative histograms obtained by FCM analysis show a reduced response to group A determinants and a preserved normal response to other human RBC antigens in mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. The dotted lines represent the negative control staining of human A-RBCs with secondary mAb alone (PE-conjugated rat anti–mouse IgM mAbs). Thin and solid lines represent staining of human O-RBCs and A-RBCs, respectively, with 20-fold–diluted mouse serum plus PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgM mAbs. (B) The ratio of the median fluorescence intensity of staining of A-RBCs to that of O-RBCs represents the anti-A determinant Ab level. Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown. The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 5; mice receiving CsA alone, n = 4; mice receiving a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5. *P < .05.

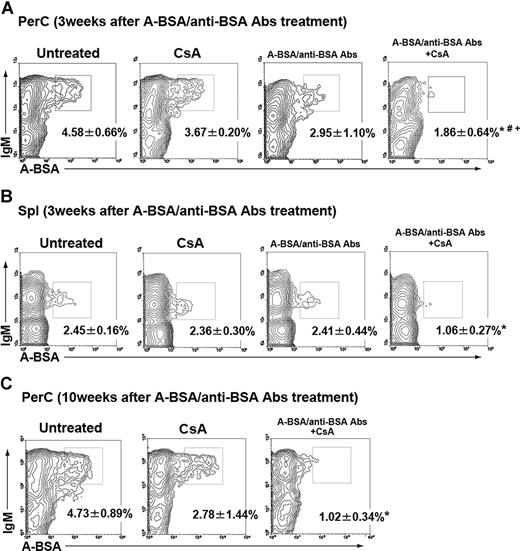

Reduction in B cells with receptors for A carbohydrates in mice that received combined A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment

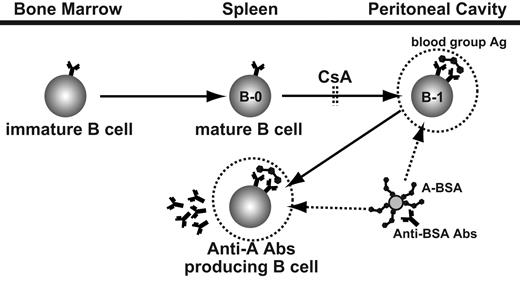

B cells with receptors for A carbohydrates were quantified in mice treated with either A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone, CsA alone, or a combination of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA by surface staining with FLUOS-labeled synthetic A-BSA. To boost putative B-cell populations with anti–A carbohydrate receptors, mice were immunized with a single injection (2 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs) or 2 injections of 5 × 108 A-RBCs (8 and 9 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs). At 8 days after the immunization, Spl and PerC cells from these animals were analyzed for B cells expressing anti-A receptors. A-BSA–binding Spl and PerC B cells were detected in mice treated with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone, although their frequency was somewhat reduced when compared with those in untreated control mice. CsA treatment alone did not influence the frequency of these cells. However, their frequency was markedly reduced in mice treated with both A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA at both time points (Figure 6). These results are consistent with the A-BSA/anti-BSA Ab treatment temporarily depleting B cells responding to A carbohydrate determinant, and CsA treatment prevents the replenishment of these cells by blocking the development of new cells from precursors (Figure 7).

Absence of B cells with receptors for group A carbohydrates in mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. Mice that were either untreated or treated with CsA alone, a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs, or A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs along with CsA were intraperitoneally immunized with a single injection (2 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs) or 2 injections of 5 × 108 A-RBCs (8 and 9 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs). Spl and PerC cells were prepared from these mice 8 days after the last immunization (3 or 10 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs). The cells were stained with FLUOS-conjugated A-BSA or control FLUOS-conjugated BSA along with biotinylated anti-mouse IgM mAb. The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis show an absence of A-BSA-binding B cells in the PerC (A,C) and Spl (B) of mice that received combined A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. To ensure statistical significance, data on 105 PerC cells and 2 × 105 Spl cells were collected for each sample. The frequency of A-BSA–binding B cells was calculated by subtracting the percentage of sIgM+ cells stained with control FLUOS-conjugated BSA from the percentage of sIgM+ cells stained with FLUOS-conjugated A-BSA. Percentages of total sIgM+ B cells are shown. Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown (*P < .01 when compared with the data from the untreated control mice; #P < .01 when compared with the data from mice treated with CsA alone; and +P < .01 when compared with the data from mice treated with mice treated with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone). (A,B) The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 6; mice that received CsA alone, n = 5; mice received only A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone, n = 5; and mice that received a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5. (C) The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 5; mice receiving CsA alone, n = 4; and mice receiving a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5.

Absence of B cells with receptors for group A carbohydrates in mice that received A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. Mice that were either untreated or treated with CsA alone, a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs, or A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs along with CsA were intraperitoneally immunized with a single injection (2 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs) or 2 injections of 5 × 108 A-RBCs (8 and 9 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs). Spl and PerC cells were prepared from these mice 8 days after the last immunization (3 or 10 weeks after the injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs). The cells were stained with FLUOS-conjugated A-BSA or control FLUOS-conjugated BSA along with biotinylated anti-mouse IgM mAb. The biotinylated mAb were visualized using allophycocyanin-streptavidin. Representative contour plots obtained by FCM analysis show an absence of A-BSA-binding B cells in the PerC (A,C) and Spl (B) of mice that received combined A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and CsA treatment. To ensure statistical significance, data on 105 PerC cells and 2 × 105 Spl cells were collected for each sample. The frequency of A-BSA–binding B cells was calculated by subtracting the percentage of sIgM+ cells stained with control FLUOS-conjugated BSA from the percentage of sIgM+ cells stained with FLUOS-conjugated A-BSA. Percentages of total sIgM+ B cells are shown. Average values (± SEM) for the individual groups are shown (*P < .01 when compared with the data from the untreated control mice; #P < .01 when compared with the data from mice treated with CsA alone; and +P < .01 when compared with the data from mice treated with mice treated with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone). (A,B) The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 6; mice that received CsA alone, n = 5; mice received only A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone, n = 5; and mice that received a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5. (C) The number of animals in each group was as follows: untreated control, n = 5; mice receiving CsA alone, n = 4; and mice receiving a single injection of A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs and daily administration of CsA, n = 5.

A schematic view of anti–blood group A Ab-producing cell development and strategy for the persistent elimination of these cells by using synthetic blood group A carbohydrates conjugated with BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and CsA. Synthetic A carbohydrates conjugated with BSA target already differentiated B cells and Ab-producing cells with anti–A carbohydrate specificity. The subsequently administered anti-BSA Abs bind the BSA epitopes of A carbohydrate BSA binding to B cells with anti-A specificity. This Ag-Ab binding leads to specific elimination of anti–A carbohydrate IgM-producing cells and their precursor B-1 cells. Stimulation with group A carbohydrate determinants leads to the differentiation of new B-1 cells with anti-A specificity; however, this differentiation is blocked by CsA.

A schematic view of anti–blood group A Ab-producing cell development and strategy for the persistent elimination of these cells by using synthetic blood group A carbohydrates conjugated with BSA, anti-BSA Abs, and CsA. Synthetic A carbohydrates conjugated with BSA target already differentiated B cells and Ab-producing cells with anti–A carbohydrate specificity. The subsequently administered anti-BSA Abs bind the BSA epitopes of A carbohydrate BSA binding to B cells with anti-A specificity. This Ag-Ab binding leads to specific elimination of anti–A carbohydrate IgM-producing cells and their precursor B-1 cells. Stimulation with group A carbohydrate determinants leads to the differentiation of new B-1 cells with anti-A specificity; however, this differentiation is blocked by CsA.

Discussion

Hyperacute and delayed vascular rejection in ABO-incompatible organ transplantations is triggered by the binding of anti-A/B Abs to A/B carbohydrate epitopes on vascular endothelial cells of the grafted organ. This activates complement, platelet aggregation, and inflammation, leading to intravascular thrombosis and occlusion of blood flow. For inhibiting early rejection, Cooper et al proposed treatment with synthetic A/B trisaccharide that targets A/B terminal carbohydrate epitopes. They demonstrated that the continuous intravenous infusion of this trisaccharide prolonged ABO-incompatible cardiac allograft survival and prevented Ab-mediated rejection in baboons. Neutralization of anti-A/B Ab activity through adsorption with specific synthetic trisaccharide which have high avidity for anti-A/B Abs shows potential for protecting ABO-incompatible organ grafts.

We hypothesized that the synthetic A/B trisaccharide might be capable of not only removing anti-A/B Abs from sera but also targeting B cells that recognize A/B carbohydrate epitopes for specific elimination. We have previously demonstrated that all IgM-producing cells as well as their precursor B-1 cells express high levels of BCRs (sIgM) in mice.19 This was indicated by the finding that all IgM-producing cells were eliminated in vitro from Spl cells when sIgM-expressing cells were depleted by FCM sorting using anti-IgM mAbs. In our preliminary study, similar results were observed in humans (data not shown). The presence of BCRs on IgM-producing cells suggests that cells producing a particular IgM could be targeted for specific elimination by interaction with their BCRs and corresponding antigenic epitopes. Consistent with this assumption, it has been reported that B cells responding to a major xenogenic antigen, Gal, could be targeted for specific elimination by the toxin ricin A coupled to Gal epitopes.35 Instead of using a toxin complex, which per se is an immunogenic substance with dose-limiting toxicities possibly including vascular leak syndrome, thrombocytopenia, and hepatic damage, we used nontoxic A carbohydrates conjugated to BSA. The administration of A carbohydrate–BSA into the circulation results in its specific binding to B cells with anti–A carbohydrate BCRs via the interaction of A carbohydrate epitopes with the BCRs on these B cells. The subsequently administered anti-BSA Abs bind the BSA epitopes of A carbohydrate–BSA to B cells with anti–A carbohydrate BCRs. This Ag-Ab binding induces complement-mediated toxicity and/or Ab-dependent cellular toxicity against these B cells without affecting B-cell clones with other Ab specificities. This strategy eliminated not only the anti–A carbohydrate Ab-secreting cells but also CD11b+ CD5+ B-1a cells with anti–A carbohydrate BCRs that were predominantly located in the peritoneal cavity.

Although A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs treatment eliminated both anti–A carbohydrate IgM-producing cells and their precursor B-1 cells, it could not inhibit anti-A Ab regeneration after immunization with A-RBCs. The reappearance of these Abs might be due to the replenishment of B cells specific for A carbohydrates, because A-BSA–binding Spl and PerC B cells were detected in mice treated with A-BSA/anti-BSA Abs alone after the immunization (Figures 4,Figure 5–6). Based on our recent demonstration that PerC CD11b+ B-1 cells are precursors of splenic IgM-producing cells,33 and those by other researchers that the PerC B-1 cells are differentiated through Ig gene rearrangement following stimulation with TI-2 Ags (the induced differentiation hypothesis),14,,–17 it is conceivable that B-1 cells specific for A carbohydrates, even after their transient depletion, might newly develop from precursor B cells through V(D)J recombination due to stimulation with A carbohydrates. B-cell responses to CsA in vivo and in vitro is reported to block TI-2 stimulation,16,36 Furthermore, B-1 cell differentiation following stimulation with TI-2 Ags can be blocked by CsA treatment.18 Since CsA suppresses the action of the nuclear factor, which is required for V(D)J recombination in precursor B cells,37,38 it might selectively affect precursors of B-1 cells. However, it may not affect well-differentiated B-1 cells or B cells that are actively producing Abs because these cells no longer require V(D)J recombination. This possibility would explain mechanisms underlying our findings that specific elimination of both Ab-producing cells and B-1 cells with anti-A specificity and subsequent CsA therapy lead to lasting inhibition of Ab production specific for A carbohydrates.

Although survival rates of ABO-incompatible organ allografts have consistently improved with the improving B-cell and antibody-directed immunosuppressive therapies currently available, they remain inferior to those of ABO-compatible transplantation. One-year graft survival rates of approximately 50% to 60% following cadaveric ABO-incompatible kidney, liver, or heart transplantation, compared with 70% to 80% for an ABO-compatible organ, have been reported.39 However, ABO-mismatched liver and heart transplantation shows improved results in infants and young children compared with adults.39,–41 Human infants manifest several aspects of immunologic immaturity, notably deficiency of humoral responsiveness to stimulation with carbohydrate TI-2 antigens.42 This includes development of isohemagglutinins or “natural” antibodies to nonself A/B blood group antigens, which remain low during the first months of life.43,44 On a trial of ABO-incompatible heart transplantation in infants, there were no cases of hyperacute or acute humoral rejection, nor clinical problems attributable to blood group incompatibility under the standard immunosuppression without splenectomy.41 Analysis of the peripheral blood B cells from patients who had received ABO-incompatible heart grafts in their infancy showed that these cells were simultaneously incapable of producing antibodies against donor type A or B blood group antigens, yet produced antibodies against nondonor polysaccharides. Moreover, B lymphocytes with BCRs specific for donor-type A and B antigens were absent. These data suggest that anergy does not have a role in this setting, and that antigen-specific B cells are tolerized by deletion or receptor editing.45 A similar tolerant state among A Ag-specific B cells has also been observed following blood group A-to-O pediatric liver transplantation.46 However, it is important to note that in this setting, almost every recipient tolerant to donor type A/B antigens was treated with calcineurin inhibitors to prevent T-cell–mediated rejection of allografts. Consistent with our findings that calcineurin inhibitors block segregation to CD5+ B-1a cells, the proportion of B-1a cells in peripheral blood was significantly reduced in patients persistently taking either CsA or tacrolimus in our preliminary study (data not shown). Since B-1 cells specific for blood group A/B carbohydrates are thought to be developed upon stimulation by gastrointestinal bacteria during maturation,43 cell differentiation might be suppressed under the cover of calcineurin inhibitors. Such an interpretation would be involved in mechanisms for the development of B-cell tolerance to donor blood group A/B antigens after ABO-incompatible heart or liver transplantation during infancy.

In conclusion, B cells with receptors for A carbohydrates, which belong to the CD5+ CD11b+ B-1a subset, were temporarily eliminated by injecting synthetic A carbohydrates conjugated to BSA and anti-BSA Abs. Subsequent treatment with CsA, which blocks the B-1a cell differentiation, completely inhibited the reappearance of these B cells. This strategy thereby persistently prevented anti-A Ab production, while maintaining normal serum Ig levels.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Takashi Onoe for his advice and encouragement.

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for scientific research (B 18390348), and (B 18390349) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science as well as a 2005 Novartis Ciclosporin Pharmaco-Clinical Forum research grant.

Authorship

Contribution: H.O. desighed the research and wrote the paper. T.I. performed the research and analyzed data. W.Z. and Y.T. performed the research. K. Ishiyama and K. Ide analyzed data. T.A. reviewed the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hideki Ohdan, Department of Surgery, Division of Frontier Medical Science, Programs for Biomedical Research, Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, Hiroshima University, 1-2-3 Kasumi, Minami-Ku, Hiroshima, Japan; e-mail:hohdan@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal