Abstract

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) is characterized by widespread involvement of the bone marrow at the time of diagnosis, implying continuous homing of WM cells into the marrow. The mechanisms by which trafficking of the malignant cells into the bone marrow has not been previously elucidated. In this study, we show that WM cells express high levels of chemokine and adhesion receptors, including CXCR4 and VLA-4. We showed that CXCR4 was essential for the migration and trans-endothelial migration of WM cells under static and dynamic shear flow conditions, with significant inhibition of migration using CXCR4 knockdown or the CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100. Similarly, CXCR4 or VLA-4 inhibition led to significant inhibition of adhesion to fibronectin, stromal cells, and endothelial cells. Decreased adhesion of WM cells to stromal cells by AMD3100 led to increased sensitivity of these cells to cytotoxicity by bortezomib. To further investigate the mechanisms of CXCR4-dependent adhesion, we showed that CXCR4 and VLA-4 directly interact in response to SDF-1, we further investigated downstream signaling pathways regulating migration and adhesion in WM. Together, these studies demonstrate that the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis interacts with VLA-4 in regulating migration and adhesion of WM cells in the bone marrow microenvironment.

Introduction

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) is a low-grade lymphoma characterized by the presence of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma cells in the bone marrow and the secretion of a monoclonal IgM protein.1,2 The widespread involvement of the bone marrow (BM) with malignant cells at the time of diagnosis implies continuous entry (homing) and exit (egress) of WM cells in and of the BM.2 In addition, involvement of the lymph nodes and hepatosplenomegaly occurs in approximately 20% of the patients and correlates with poor prognosis in some studies.3 However, the mechanisms by which homing of WM cells into the BM and their adhesion to the microenvironment have not been previously studied

Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines that regulate recruitment and homing of lymphocytes and leucocytes into targeted tissues.4 Chemokines are small (8-11 kDa) chemotactic proteins that are secreted by various cells under the influence of inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and cancer cells.4,5 On release they create a chemical gradient in the microenvironment and attract cells bearing relevant chemokine receptors.4-6 Engagement of chemokine receptors by cells in blood flow mediates their adhesion to endothelium, transendothelial migration, and tissue invasion.7-9 Chemokines are subdivided into 4 classes: CXC or alpha, CC or beta, C or gamma, and CX3C or delta chemokines.4 Migration and adhesion are initiated by site-specific ligands in the BM milieu that induce homing of blood-borne cells from the intravascular space through the endothelial cell layer and into the BM milieu.

Homing is thought to be a coordinated, multistep process, which involves signaling by the chemokine stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1), activation of lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), VLA-4 and VLA-5, and cytoskeleton rearrangement.10,11 There are 4 major families of cell adhesion molecules.12,13 These are the immunoglobulin (Ig) superfamily cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), integrins, cadherins, and selectins.12,13 Integrins are noncovalently linked heterodimers of α and β subunits.14 Members of the β1 integrins (also called VLA proteins) combine with the α subunits to form the different types of VLA proteins. α4β1 integrin (VLA-4) and α5β1 integrin (VLA-5) are highly expressed in malignant plasma cells and mediate adhesion to fibronectin and VCAM.15 Integrin-mediated adhesion of malignant cells to fibronectin confers protection against drug-induced apoptosis.16 SDF-1 has been reported to induce firm adhesion and migration by inducing activation of integrins LFA-1, VLA-4, and VLA-5 on hematopoietic stem cells.10,17-19 Interestingly, adhesion molecules may trigger signals for both enhanced CXCR4 expression and increased function.20 In addition, fibronectin and VCAM sensitize hematopoietic stem cells to migration toward low levels of SDF-1.19 These findings suggest that the interactions between CXCR4 and adhesion molecules are complex and constitute a 2-way pathway. In WM, the role of chemokines and adhesion molecules, specifically the role of SDF-1/CXCR4 axis and VLA-4 protein in the process of homing and adhesion, has not been previously explored.

In this study, we observed that WM cells express high levels of chemokine receptors and adhesion receptors. We then focused our studies on the role of SDF-1/CXCR4 and VLA-4 in the regulation of adhesion and homing of WM cells to BM microenvironment, specifically to endothelial cells and stromal cells present in the BM milieu. We found that that CXCR4 and VLA-4 directly interact in response to SDF-1. We further investigated downstream signaling pathways regulating migration and adhesion in WM and observed that SDF-1/VLA-4 signaling activates the PI3K, ERK, and PKC pathways. In addition, we showed that inhibition of CXCR4 by AMD3100 or CXCR4 knockdown leads to inhibition of migration, transendothelial migration, and adhesion. Together, these studies demonstrate that the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis interacts with VLA-4 in regulating trafficking and adhesion of WM cells to the BM.

Methods

Cells

The WM cell lines (BCWM.1 and WSU-WM) were used in this study. BCWM.1 (kind gift from Dr Treon, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA) is a recently described WM cell line that has been developed from a patient with untreated IgM kappa WM.21 The cells express the typical lymphoplasmacytic phenotype. WSU-WM was a kind gift from Dr Al Katib (Wayne State University, Detroit, MI). All cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 2 mM of l-glutamine, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The umbilical vein endothelial HUVEC cell line (Cambrex, Walkersville, MD) was cultured in EGM-2 MV media (Cambrex) reconstituted according to the manufacturer.

Patient samples were obtained after approval from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Primary WM cells were obtained from BM samples using CD19+ micro-bead selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) with more than 90% purity as confirmed by flow cytometric analysis with monoclonal antibody reactive to human CD20-PE (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA). The negative fraction of the BM cells was cultured until an adherent cell layer developed. These cells were used as stromal cells for the coculture experiments. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from healthy volunteers by Ficoll-Hipaque density sedimentation.

Reagents

CXCR4 antibody was purchased from Affinity Bioreagents (Golden, CO). AMD3100 and pertussis toxin (PTX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The PI3K inhibitor LY294002 was purchased from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) and the MEK/MAPKinase inhibitor PD098059 from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). The inhibitory anti–VLA-4 antibody (CD49d) was purchased from BD Biosciences. SDF-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and bortezomib was provided from Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA).

Lentivirus shRNA vector construction and CXCR4 gene transduction

To further determine the role of CXCR4 in adhesion and regulation of downstream signaling pathways in WM, we established a CXCR4 knockout BCWM.1 cell line using lentivirus system as previously described.22 The sense oligonucleotide sequence for construction of CXCR4 shRNA was as follows: CTGCCTTACTACATTGGGAT (RNA Resortium, Boston, MA). The target sequence of CXCR4 was inserted into pLKO.1 vector. ShCXCR4 construct or pLKO.1 vector was cotransfected with pVSV-G and p8.9 plasmids into 293T packaging cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). BCWM.1 cells were then transduced with the supernatants containing the released virus mixed with equal amount of reconstituted RPMI 10% after 48 hours and 72 hours. Two days after infection, cells were treated with puromycin 250 ng/mL (Invitrogen) for 2 weeks. Stable knockdown was confirmed by immunoblotting and reverse-transcribed polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for CXCR4 expression.

RT-PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocols and treated with DNaseI (QIAGEN) to digest contaminated DNA. cDNA was synthesized using the Superscript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen) with an oligo(dT) primer. The amount of cDNA subjected to PCR was normalized by the intensity of GAPDH bands detected by RT-PCR. PCR products were examined by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose gel. GAPDH primers: sense GACATCAAGGTGGTGAA and antisense TGTCATACCAGGAAATGAGC and CXCR4 primers: sense TTCTACCCCAATGACTTGTG and antisense ATGTAGTAAGGCAGCAACA.

Flow cytometric analyses

We determined chemokine and adhesion receptors or ligands, and CD20 cell surface expression by flow cytometric analysis (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) using CD20-PE, CXCR1, 2, 3, 4, 5-PE, CXCR7-biotin, CCR1-biotin, CCR2, 4, 5, 6, 7-PE, LFA-1, VLA-4, ICAM-VCAM-PE antibodies (BD Biosciences).

SDF-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Quantitative SDF-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems) was used to determine the level of SDF-1 in the peripheral blood serum and BM supernatant of WM patients and normal controls, according to manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, samples were plated into wells precoated with a monoclonal antibody specific for SDF-1 (R&D Systems). An enzyme linked polyclonal antibody specific for SDF-1 was then added. The optical density was measured using a microplate reader set to 450 nm with correction at 540 nm.

Static transwell migration assays

Migration was determined using the transwell migration assay (Corning Life Sciences, Acton, MA) as previously described.22 BCWM.1, CXCR4-knockdown BCWM.1, WM-WSU, and CD19+ BM WM cells (2 × 105) were treated with reagents for 60 minutes and then placed in the migration chambers with 1% fetal calf serum medium in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM. After 4 hours of incubation, cells that migrated to the lower chambers were counted using a Beckman Coulter cell counter. Triplicates of each experiment were performed.

In additional transwell studies to assess migration across an endothelial barrier, 2 × 104 of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were plated on filters and grown in EVM medium for 24 hours on the inner side of transwell inserts (transwell-clear, 4.0-μM pores) before the performance of each assay. The next day, the HUVECs were activated to induce maximal expression of cell adhesion molecules by incubation with TNF-α 250 U/mL for 6 hours. The transwell migration assay was performed as described. The number of WM cells that migrated through the endothelial cell layer and into the lower chambers was counted using a Beckman Coulter cell counter as described. Control wells containing no WM cells demonstrated no migration of endothelial cells into the lower chambers. Triplicate of each experiment were performed.

Real-time transendothelial migration analysis in a transwell flow chamber

This technique was performed as previously described.23 HUVECs (passage 2 or 3) were plated at 50% confluence and then cultured on the underside of fibronectin-coated transwell inserts (transwell-clear, 0.4-μM pores) for an additional 48 hours to allow complete confluence. Confluent HUVECs (verified by microscopy) were stimulated for 12 hours before each experiment with TNF-α (20 ng/mL). HUVEC-coated transwell inserts were then placed into the flow chamber and mounted on the stage of an overhead phase-contrast microscope (Eclipse E-600; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) connected to a digital signaling processing CCD camera (ELMO Manufacturing, Plainview, NY). The insert was then rinsed and filled with transendothelial migration (TEM) medium (HBSS with 1 mM of calcium chloride, 5 mM of N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, and 1 mg/mL of bovine serum albumin) alone or with SDF-1 12 nM, constituting the basal chamber. The HUVEC-coated side was overlaid with SDF-1 (apical presentation at 0, 0.5, or 1 nM for 2 minutes) and was washed extensively before BCWM.1 cell perfusion (3 × 106/trial) at defined shear stress generated by syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Natick, MA). All experiments were performed at 37°C. The perfusion period was recorded in real time (HS-U748; Mitsubishi Digital Electronics America, Irvine, CA). For all experiments, WM cells were perfused in TEM medium into the chamber and allowed to settle under flow at 0.4 dyne/cm2 for 2 minutes over the HUVEC monolayer, allowing proximate apposition of the cells to the endothelium within the dimensions of the flow chamber but of insufficient duration to elicit any adherence. Shear stress was then adjusted to 1.0 dyne/cm2 for 2 minutes to allow WM accumulation on the monolayer and then was increased to 2.0 dyne/cm2, a physiologic level previously found to support TEM. This level of shear stress either was maintained for 11 more minutes. Motion analysis and TEM determination were performed manually by an observer blinded to the experimental conditions used. BCWM.1 untreated or treated with AMD3100 (50 μM for 2 hours) were tested using this technique.

Adhesion assays with fibronectin, stromal cells, and endothelial cells

We used an in vitro adhesion assay (Innocyte ECM Cell Adhesion Assay) consisting of 96-well plates coated with fibronectin, a ligand of VLA-4 (EMD Biosciences). We performed adhesion assay using WM cells (BCWM.1, CXCR4-knockdown BCWM.1, WM-WSU, and CD19+ primary WM cells) in the presence or absence of SDF-1. The cells (2 × 105) were incubated in the 96-well plate of adhesion for 1 hour in 37°C and washed with phosphate-buffered saline to remove all nonadherent cells. Calcein AM was then added for 1 hour, and the degree of fluorescence was measured using a spectrophotometer at excitation wavelength 485 nm and emission wavelength 520 nm. BSA-coated well served as negative control and poly-L-lysine–coated wells served as positive control for unspecific attachment.

Similarly, we examined adhesion to both stromal cells and endothelial cells. For stromal cell adhesion assays, a confluent monolayer of stromal cells was generated by plating (5 × 103) cells in a 96-well plate. After 24 hours of incubation, WM cells (2 × 105) were incubated in the 96-well plates and adhesion assay was performed as described. For endothelial cell assays, HUVECs (5 × 103) were plated in 96-well plates for 24 hours until confluent. The cells were activated using TNF (10 ng/mL for 1 hour). The wells were washed and SDF-1 (30 nM) was added in the treatment wells with phosphate-buffered saline in the control wells. WM cells were added as described and adhesion assay was performed as described.

DNA synthesis

Proliferation was measured by DNA synthesis. WM cells were incubated in the presence of media or AMD3100 with or without bortezomib 0 to 10 nM (Millennium Pharmaceuticals). DNA synthesis was measured by [3H]-thymidine ([3H]-TdR; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA) uptake as previously published.24 Briefly, cells were pulsed with 10 μL of [3H]TdR (0.0185 MBq/well [0.5 μCi/well]) during the last 8 hours of 48-hour cultures. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Immunoblotting

WM cells were harvested and lysed using lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) reconstituted following manufacturer recommendations. Whole-cell lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The antibodies used for immunoblotting included: anti-phospho (p)-Akt (Ser473), anti-Akt, anti–p-ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), anti-ERK1/2, and anti–pan-p-PKC (Cell Signaling Technology) as well as anti–β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Coimmunoprecipitation

BCWM.1 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of SDF-1. Immunoprecipiation was performed as previously described and following the manufacturer recommendations (Cell Signaling Technology). Briefly, following CXCR4 immunoprecipitation, the cells were then suspended and samples were next run on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane and blotted using anti–VLA-4 antibody.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance of mean (± SD) differences observed in drug-treated versus control samples was determined using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The minimal level of significance was a P less than .05.

Results

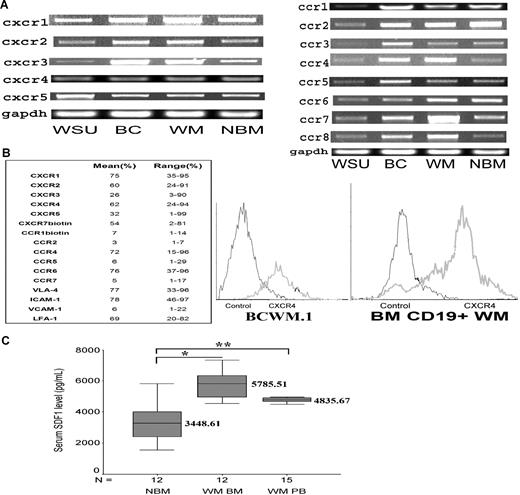

Primary WM cells and BCWM.1 highly express chemokine receptors

We first examined the expression pattern of 13 CXC and CC chemokine receptors (CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, CXCR5, CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, CCR7, and CCR8) in WM cells using RT-PCR and flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 1A, WM cell lines (BCWM.1 and WMWSU), malignant CD19+ WM cells and normal CD19+ lymphocytes obtained from BM of healthy donors demonstrated expression of all CXC and CC chemokine receptors tested. Similarly, as shown in Figure 1B, we determined the expression level of chemokine (CXCR and CCR) receptor expression in 10 CD19+ malignant WM samples and showed a wide variability in the expression level of these receptors as well as the expression of adhesion receptors (VLA-4 and LFA-1) and adhesion ligands (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1). We then specifically focused our studies on the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and its ligand SDF-1, given their well-established role in homing and adhesion in other malignancies and hematopoietic stem cells.25 CXCR4 was highly expressed in all cell lines and CD19+ WM and normal control samples as shown in Figure 1B. CXCR4 was highly expressed on malignant CD19+ WM (N = 10, mean = 62%, range = 24%-94%) cells and BCWM.1 (mean = 72%) cell line. Given that CXCR4 expression did not significantly differ between normal and malignant CD19+ cells, we sought to investigate whether SDF-1 level is up-regulated in the BM of patients with WM compared with normal control. Quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for SDF-1 of BM of normal and WM samples showed that the mean expression of SDF-1 in the BM of WM patients (N = 12, mean = 5785, range = 4529-7343 pg/mL) was significantly higher compared with that of normal controls (N = 12, mean = 3449, range = 1541-6440 pg/mL; P = .001), indicating that SDF-1 level is higher in the BM of WM patients as shown in Figure 1C. Similarly, the level of SDF-1 in the PB patients (N = 15, mean = 4771, range = 4255-5802 pg/mL; P = .004) was significantly higher compared with that of normal controls.

Chemokine receptors expression in WM. (A) CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, CXCR5, CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, CCR7, and CCR8 expression in WM cell lines, including WM-WSU (WSU), BCWM.1 (BC), a representative patient sample (WM) and a representative normal bone marrow CD19+ cells (NBM). A total of 3 patient samples and 3 normal marrow samples were tested. GAPDH was used as control. (B) Chemokine receptors and adhesion molecule expression and CXCR4 expression in 10 patient samples using flow cytometry. The table shows the mean and range of expression of all the CXCR, CCR receptors, and adhesion molecules. The right panel shows BCWM.1 cell line and CD19+ WM cells from a primary patient using flow cytometry and compared with IgG1 control. (C) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for SDF-1 level (pg/mL) demonstrates that the level of SDF-1 is significantly higher in the bone marrow of WM patients (N = 12, *P = .001.) and peripheral blood of WM patients (N = 15, **P = .004) compared with healthy volunteer control BM supernatants (N = 12).

Chemokine receptors expression in WM. (A) CXCR1, CXCR2, CXCR3, CXCR4, CXCR5, CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR4, CCR5, CCR6, CCR7, and CCR8 expression in WM cell lines, including WM-WSU (WSU), BCWM.1 (BC), a representative patient sample (WM) and a representative normal bone marrow CD19+ cells (NBM). A total of 3 patient samples and 3 normal marrow samples were tested. GAPDH was used as control. (B) Chemokine receptors and adhesion molecule expression and CXCR4 expression in 10 patient samples using flow cytometry. The table shows the mean and range of expression of all the CXCR, CCR receptors, and adhesion molecules. The right panel shows BCWM.1 cell line and CD19+ WM cells from a primary patient using flow cytometry and compared with IgG1 control. (C) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for SDF-1 level (pg/mL) demonstrates that the level of SDF-1 is significantly higher in the bone marrow of WM patients (N = 12, *P = .001.) and peripheral blood of WM patients (N = 15, **P = .004) compared with healthy volunteer control BM supernatants (N = 12).

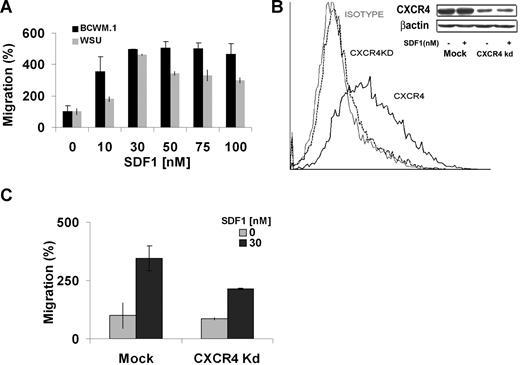

CXCR4 is required for migration in WM

We next examined the functional effect of SDF-1 on WM cells. We first observed that SDF-1 induces dose-dependent migration of WM cell lines, with 30 nM inducing maximum migration of BCWM.1 and WM-WSU cell lines as shown in Figure 2A. Higher doses did not induce significant increase in migration beyond 30 nM. To further investigate the role of CXCR4 in WM, we developed a knockdown CXCR4 cell line. As shown in Figure 2B, CXCR4 expression was significantly decreased in the knockdown cell line compared with the mock control using flow cytometry. Similar results were confirmed using RT-PCR and immunoblotting techniques. To confirm that CXCR4 is essential for migration in response to SDF-1, we performed transwell migration assay using the CXCR4 knockdown cell line. As shown in Figure 2C, the mock cell line migrated in response to SDF-1, whereas the CXCR4 knockdown cell line demonstrated minimal migration, indicating that CXCR4 is essential for SDF-1 dependent migration in WM.

Migration of BCWM.1 and CXCR4 knockdown cell lines. (A) Transwell migration assay using BCWM.1 and WM-WSU (WSU) WM cell lines. SDF-1 0 to 100 nM was placed in the lower chambers, and migration was determined after 4 hours. Maximum migration occurred at approximately 30 nM with no further increase in migration beyond 30 nM. (B) CXCR4 knockdown BCWM.1 cell line (CXCR4Kd) was generated using lentivirus infection. Flow cytometry for CXCR4 expression was performed using IgG1 isotype control, CXCR4 Kd cell line, and mock BCWM.1 showing no CXCR4 expression in the Kd cell line. Similarly, Western blotting demonstrates negligible CXCR4 expression in the Kd cell line compared with mock BCWM.1 (C) Transwell migration assay using CXCR4Kd cell line compared with Mock-infected BCWM.1 cell line showing significant migration with SDF-1 30 nM, whereas the CXCR4 Kd cell line showed minimal migration in response to SDF-1.

Migration of BCWM.1 and CXCR4 knockdown cell lines. (A) Transwell migration assay using BCWM.1 and WM-WSU (WSU) WM cell lines. SDF-1 0 to 100 nM was placed in the lower chambers, and migration was determined after 4 hours. Maximum migration occurred at approximately 30 nM with no further increase in migration beyond 30 nM. (B) CXCR4 knockdown BCWM.1 cell line (CXCR4Kd) was generated using lentivirus infection. Flow cytometry for CXCR4 expression was performed using IgG1 isotype control, CXCR4 Kd cell line, and mock BCWM.1 showing no CXCR4 expression in the Kd cell line. Similarly, Western blotting demonstrates negligible CXCR4 expression in the Kd cell line compared with mock BCWM.1 (C) Transwell migration assay using CXCR4Kd cell line compared with Mock-infected BCWM.1 cell line showing significant migration with SDF-1 30 nM, whereas the CXCR4 Kd cell line showed minimal migration in response to SDF-1.

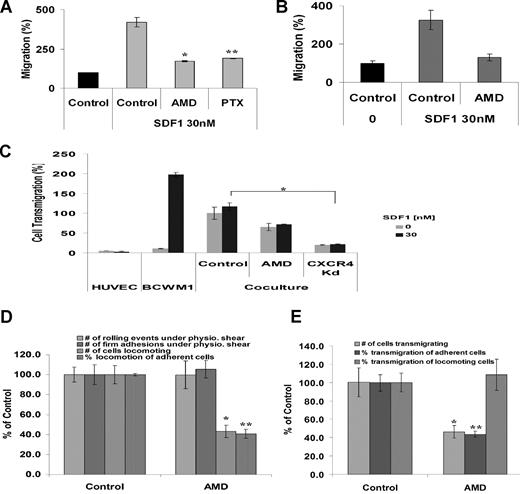

Specific inhibition of CXCR4 abrogates transendothelial migration under static and shear flow conditions

To further characterize the functional role of CXCR4 in WM migration, we investigated the role of a specific inhibitor to CXCR4, AMD3100 on migration in transwell chambers. As shown in Figure 3A, there was significant increase in migration of BCWM.1 in response to 30 nM SDF-1, whereas pretreatment of BCWM.1 with AMD3100 (20 μM for 2 hours, *P < .05) demonstrated significant reduction of migration in response to SDF-1 in static transwell migration assays. Serial concentrations of AMD3100 (0-200 μM) demonstrated significant decrease in migration using 20 μM with no further decrease in migration with higher doses (data not shown). We therefore used 20 μM concentrations in all further studies. CXCR4 is a G-protein coupled receptor, with Gi protein regulating cytokine secretion and chemotaxis in most cell types. Therefore, we sought to determine whether the migratory role of CXCR4 in WM is regulated by PTX-sensitive Gi protein. As shown in Figure 3A, PTX (200 ng/mL, **P < .05) inhibited migration of BCWM.1 to the same degree as AMD3100, indicating that the migratory function of CXCR4 is through the Gi protein. Different concentrations of PTX (0-500 ng/mL), and maximum inhibition of migration occurred at 200 ng/mL, with no further inhibition of migration at higher doses (data not shown). We further confirmed the migratory role of CXCR4 in primary CD19+ WM cells obtained from the BM of patients. As shown in Figure 3B, untreated WM cells migrated in response to SDF-1 30 nM, whereas pretreatment of the cells with AMD3100 (20 μM) significantly inhibited migration.

AMD3100 inhibits migration and transendothelial migration under static and shear flow conditions in BCWM.1. (A) Transwell migration assay was performed using no SDF-1 (▤ for control) or with the presence of SDF-1 30 nM (). BCWM.1 pretreated with AMD3100 20 μM for 2 hours inhibited migration by 50% compared with control in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM. Similarly, pretreatment of BCWM.1 with PTX 200 ng/mL for 2 hours inhibited migration in response to SDF-1 similar to AMD3100. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05, **P < .05). (B) Migration of CD19+ primary WM cells from 3 patients demonstrated significant migration in response to SDF-1 30 nM compared with control (no SDF-1). Pretreatment of the cells with AMD3100 20 μM for 2 hours showed significant reduction of migration compared with untreated cells (C) Transendothelial migration of BCWM.1. HUVECs were grown on the inner wells of the Boyden chamber migration wells until confluent. BCWM.1 untreated or pretreated with AMD3100 20 μM for 2 hours or CXCR4 knockdown BCWM.1 cell line were placed in the upper chambers with or without SDF-1 30 nM in the lower chambers. The number of cells that migrated to the lower chambers was counted after 4 hours. As shown, AMD3100 and CXCR4Kd showed decreased migration compared with control. The presence of SDF-1 did not induce significant increase in migration in the presence of endothelial cells (that secrete SDF-1), indicating that endothelial cells induce transmigration through the SDF-1 axis (*P = .04). (D) Shear flow chamber assay for rolling, firm adhesion to endothelial cells, and locomotion. Pretreatment of BCWM.1 cells with AMD3100 (20 μM for 2 hours) had no effect on rolling and firm adhesion (which are regulated by selectins) but had significant inhibition on the number of locomoting cells and the percentage of locomotion of adherent cells. Bars represent percent of untreated controls. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .001, **P = .001). (E) Shear flow chamber assay for transendothelial migration showing the number of cells transmigrating as well as the percentage of cells transmigrating from the adherent and locomoting cell populations. Pretreatment of BCWM.1 cells with AMD3100 (20 μM for 2 hours) induced significant inhibition on transendothelial migration, specifically on the adherent cell population. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .01, **P = .004).

AMD3100 inhibits migration and transendothelial migration under static and shear flow conditions in BCWM.1. (A) Transwell migration assay was performed using no SDF-1 (▤ for control) or with the presence of SDF-1 30 nM (). BCWM.1 pretreated with AMD3100 20 μM for 2 hours inhibited migration by 50% compared with control in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM. Similarly, pretreatment of BCWM.1 with PTX 200 ng/mL for 2 hours inhibited migration in response to SDF-1 similar to AMD3100. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P < .05, **P < .05). (B) Migration of CD19+ primary WM cells from 3 patients demonstrated significant migration in response to SDF-1 30 nM compared with control (no SDF-1). Pretreatment of the cells with AMD3100 20 μM for 2 hours showed significant reduction of migration compared with untreated cells (C) Transendothelial migration of BCWM.1. HUVECs were grown on the inner wells of the Boyden chamber migration wells until confluent. BCWM.1 untreated or pretreated with AMD3100 20 μM for 2 hours or CXCR4 knockdown BCWM.1 cell line were placed in the upper chambers with or without SDF-1 30 nM in the lower chambers. The number of cells that migrated to the lower chambers was counted after 4 hours. As shown, AMD3100 and CXCR4Kd showed decreased migration compared with control. The presence of SDF-1 did not induce significant increase in migration in the presence of endothelial cells (that secrete SDF-1), indicating that endothelial cells induce transmigration through the SDF-1 axis (*P = .04). (D) Shear flow chamber assay for rolling, firm adhesion to endothelial cells, and locomotion. Pretreatment of BCWM.1 cells with AMD3100 (20 μM for 2 hours) had no effect on rolling and firm adhesion (which are regulated by selectins) but had significant inhibition on the number of locomoting cells and the percentage of locomotion of adherent cells. Bars represent percent of untreated controls. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .001, **P = .001). (E) Shear flow chamber assay for transendothelial migration showing the number of cells transmigrating as well as the percentage of cells transmigrating from the adherent and locomoting cell populations. Pretreatment of BCWM.1 cells with AMD3100 (20 μM for 2 hours) induced significant inhibition on transendothelial migration, specifically on the adherent cell population. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .01, **P = .004).

The process of homing is a multistep process that includes rolling, adhesion to the endothelium, and transendothelial migration into the marrow parenchyma. To investigate this specific process, we first tested the capacity of WM cells to migrate through an endothelial cell barrier using a static transwell assay. As shown in Figure 3C, there was minimal migration of WM cells in the absence of SDF-1 in a transwell migration assay. However, when an endothelial cell layer was allowed to grow in the upper chambers of the transwell migration chambers and BCWM.1 cells were placed in the upper chambers in the absence of SDF-1, WM cells migrated at a higher rate through the endothelial cell layer and into the lower chambers. To further determine whether SDF-1 plays a role in transendothelial migration, we also performed the same experiment using SDF-1 30 nM in the lower chambers. As shown in Figure 3C, the addition of SDF-1 to endothelial cells did not lead to further migration of WM cells, indicating that most of the activity of endothelial cells on transmigration of WM cells is through SDF-1 and that further addition of SDF-1 to the media does not induce further migration. In addition, the addition of AMD3100 or the use of CXCR4 knockdown cell line led to abrogation of transendothelial migration.

Physiologically, all cell migration occurs under conditions of hemodynamic shear flow. We therefore studied the effect of rolling, adhesion to endothelial cells, and transenothelial migration of WM cells under shear flow in the presence of SDF-1 and in the presence or absence of AMD3100. We determined the effect of AMD3100 on rolling, firm adhesion, and locomotion. As shown in Figure 3D, AMD3100 did not affect rolling and firm adhesion under shear flow, which are selectin-dependent processes, indicating that CXCR4 does not regulate these processes. AMD3100 induced significant inhibition of locomotion in BCWM.1 (P = .001). Similarly, AMD3100 significantly inhibited transendothelial migration under shear flow, specifically the transmigration of adherent cells as shown in Figure 3E, confirming the essential role of CXCR4 in transendothelial migration (P = .01).

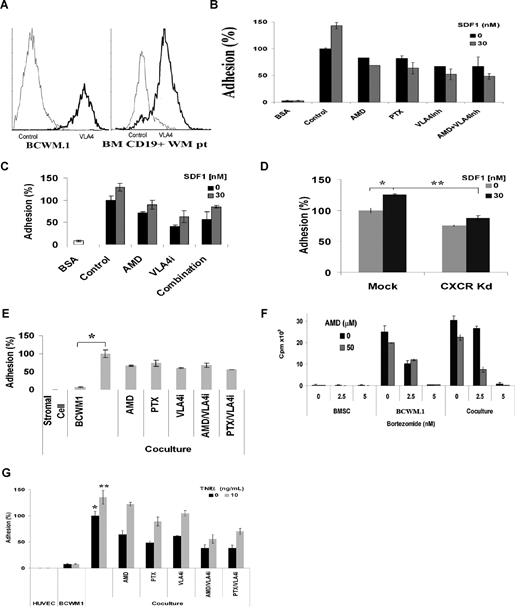

CXCR4 and VLA-4 regulate adhesion to fibronectin, stromal cells, and endothelial cells in WM, and sensitize WM cells to therapeutic agents

Integrin-mediated adhesion of malignant cells to fibronectin confers protection against drug-induced apoptosis.16 SDF-1 has been reported to induce firm adhesion and migration by inducing activation of integrins LFA-1, VLA-4, and VLA-5 on hematopoietic stem cells. To better elucidate the role of SDF-1/CXCR4 on adhesion of WM cells, we studied adhesion of WM cells to fibronectin, stromal cells, and endothelial cells in the presence or absence of CXCR4 or VLA-4 inhibitors or CXCR4 knockdown. We first observed that WM primary cells (N = 10, mean = 77%, range = 33%-96%) and WM (mean = 98%) cell lines expressed high levels of VLA-4 using flow cytometry as shown in Figure 4A. We then found that SDF-1 induced adhesion of WM cells to fibronectin and that AMD3100 (20 μM) and the VLA-4 inhibitory antibody (10 ng/mL) significantly inhibited adhesion to fibronectin. Similarly, we observed that the Gi protein regulates SDF-1 induced adhesion of WM cells to fibronectin as the use of PTX (200 ng/mL) significantly inhibited adhesion to a similar level as AMD3100. The combination of AMD3100 and VLA-4 inhibitor did not further inhibit adhesion of WM cells to fibronectin, indicating that CXCR4 and VLA-4 receptors use the same pathways of adhesion as shown in Figure 4B. Similar studies were performed using primary CD19+ cells obtained from patients as shown in Figure 4C. Similarly, we found that CXCR4 is essential for adhesion in response to fibronectin as the CXCR4 knockdown cell line showed lower adhesion compared with mock-infected BCWM.1 (Figure 4D, P = .01).

CXCR4 and VLA-4 regulate adhesion to fibronectin, stromal cells, and endothelial cells in WM and sensitize WM cells to therapeutic agents. (A) Flow cytometry for VLA-4 expression showing that BCWM.1 and CD19+ primary WM cells (N = 10) have high surface expression of VLA-4. (B) Adhesion assay with fibronectin (VLA-4 ligand). BCWM.1 showed significant increase in adhesion to fibronectin compared with BSA used as control. SDF-1 30 nM induced further increase in adhesion. Pretreatment of BCWM.1 for 2 hours with AMD3100 20 μM, PTX 200 ng/mL, and anti–VLA-4 antibody 10 ng/mL significantly inhibit adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM. (C) Adhesion of primary CD19+ cells (N = 3) alone or with SDF-1, showing increased adhesion in response to SDF-1 30 nM. Pretreatment of the cells with AMD3100 20 μM, anti–VLA-4 antibody 10 ng/mL, or the combination showed inhibition of adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1. (D) CXCR4 knockdown cell line showed lower adhesion compared with mock-infected BCWM.1, even in the presence of 30 nM SDF-1. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .04, **P = .01). (E) Inhibition of adhesion to stromal cells. Coculture of stromal cells with BCWM.1 resulted in increased adhesion (*P = .008). Pretreatment of BCWM.1 with AMD3100, anti–VLA-4 antibody, PTX, or the combination of AMD3100/anti–VLA-4 antibody, or the combination of PTX/anti–VLA-4 antibody resulted in significant inhibition of adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1. The combination of AMD3100 and anti–VLA-4 antibody did not induce further decrease in adhesion, indicating that the 2 receptors use the same pathway to regulate adhesion. (F) Coculture of stromal cells with BCWM.1. Bortezomib 2.5 and 5 nM inhibited proliferation in BCWM.1, but less when the cells were cocultured with stromal cells, indicating that stromal cells confer resistance to WM cells. However, when AMD3100 20 μM was added 2 hours before bortezomib, it increased the sensitivity of cells to bortezomib in the coculture experiments at bortezomib 2.5 nM. (G) Adhesion assay to endothelial cells. HUVECs were cultured for 24 hours. BCWM.1 were labeled with calcein AM and cocultured with HUVEC for 4 hours, with or without SDF-1. BCWM.1 showed increased adhesion to endothelial cells, and AMD3100, anti–VLA-4 inhibitor, PTX, and the combination of AMD3100/anti–VLA-4 antibody or anti–VLA-4 antibody/PTX showed decreased adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1 (*P = .009, **P = .009).

CXCR4 and VLA-4 regulate adhesion to fibronectin, stromal cells, and endothelial cells in WM and sensitize WM cells to therapeutic agents. (A) Flow cytometry for VLA-4 expression showing that BCWM.1 and CD19+ primary WM cells (N = 10) have high surface expression of VLA-4. (B) Adhesion assay with fibronectin (VLA-4 ligand). BCWM.1 showed significant increase in adhesion to fibronectin compared with BSA used as control. SDF-1 30 nM induced further increase in adhesion. Pretreatment of BCWM.1 for 2 hours with AMD3100 20 μM, PTX 200 ng/mL, and anti–VLA-4 antibody 10 ng/mL significantly inhibit adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM. (C) Adhesion of primary CD19+ cells (N = 3) alone or with SDF-1, showing increased adhesion in response to SDF-1 30 nM. Pretreatment of the cells with AMD3100 20 μM, anti–VLA-4 antibody 10 ng/mL, or the combination showed inhibition of adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1. (D) CXCR4 knockdown cell line showed lower adhesion compared with mock-infected BCWM.1, even in the presence of 30 nM SDF-1. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .04, **P = .01). (E) Inhibition of adhesion to stromal cells. Coculture of stromal cells with BCWM.1 resulted in increased adhesion (*P = .008). Pretreatment of BCWM.1 with AMD3100, anti–VLA-4 antibody, PTX, or the combination of AMD3100/anti–VLA-4 antibody, or the combination of PTX/anti–VLA-4 antibody resulted in significant inhibition of adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1. The combination of AMD3100 and anti–VLA-4 antibody did not induce further decrease in adhesion, indicating that the 2 receptors use the same pathway to regulate adhesion. (F) Coculture of stromal cells with BCWM.1. Bortezomib 2.5 and 5 nM inhibited proliferation in BCWM.1, but less when the cells were cocultured with stromal cells, indicating that stromal cells confer resistance to WM cells. However, when AMD3100 20 μM was added 2 hours before bortezomib, it increased the sensitivity of cells to bortezomib in the coculture experiments at bortezomib 2.5 nM. (G) Adhesion assay to endothelial cells. HUVECs were cultured for 24 hours. BCWM.1 were labeled with calcein AM and cocultured with HUVEC for 4 hours, with or without SDF-1. BCWM.1 showed increased adhesion to endothelial cells, and AMD3100, anti–VLA-4 inhibitor, PTX, and the combination of AMD3100/anti–VLA-4 antibody or anti–VLA-4 antibody/PTX showed decreased adhesion, even in the presence of SDF-1 (*P = .009, **P = .009).

To further confirm the role of CXCR4 in adhesion in WM, we performed an adhesion assay of WM cells to BM stromal cells. As shown in Figure 4E, there was a significant increase in adhesion of BCWM.1 to stromal cells (P = .008). This effect was inhibited by AMD3100 (20 μM), indicating a role of CXCR4 in WM-stromal cell adhesion. Similarly, PTX (200 ng/mL) inhibited this adhesion, indicating that it is Gi protein-mediated. The VLA-4 neutralizing antibody (10 ng/mL) inhibited migration to a similar degree. Difference concentrations of anti–VLA-4 antibody (0-100 ng/mL) were tested, and 10 ng/mL showed maximum inhibition of adhesion, with no further inhibition of adhesion at higher concentrations (data not shown). The combination of AMD3100 and anti–VLA-4 did not further decrease adhesion, again showing that adhesion to stromal cells involves both VLA-4 and CXCR4 in the same signaling pathway. Similarly, the combination of PTX and anti–VLA-4 did not further inhibit adhesion.

Previous studies have demonstrated that adhesion of WM cells to marrow stromal cells confers growth and resistance of WM cells. Therefore, we investigated the effect of AMD3100 on sensitizing WM cells to cytotoxicity by low doses of bortezomib. As shown in Figure 4F, the presence of stromal cells in coculture with WM cells induced proliferation of BCWM.1 compared with BCWM.1 alone. AMD3100 20 μM slightly inhibited the growth of BCWM.1, especially in the presence of stromal cells. Bortezomib 2.5 nM induced significant cytotoxicity in BCWM.1. However, in coculture with stromal cells, the effect of bortezomib 2.5 nM was diminished, indicating that adhesion of WM cells to stromal cells induces resistance to low doses of bortezomib. Interestingly, the addition of AMD3100 20 μM restored the sensitivity of BCMW.1 to low doses of bortezomib, even in the presence of stromal cells. Similarly, we showed that the coculture of BCWM.1 with endothelial HUVECs, whether activated with TNF-α or not, induced significant adhesion of WM cells (P = .009). In addition, AMD3100, PTX, anti–VLA-4, and the combination of AMD3100 and anti–VLA-4 antibody, or PTX and anti-VLA-4 inhibited adhesion of WM cells to endothelial cells as shown in Figure 4G.

CXCR4 and VLA-4 cointeract and regulate downstream PI3K and ERK/MAPK pathways

To further investigate the mechanism of interaction of VLA-4 and CXCR4, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assay. As shown in Figure 5A, CXCR4 and VLA-4 coimmunoprecipitated in the presence of SDF-1, indicating a direct interaction of those 2 receptors when activated. We then sought to investigate downstream signaling pathways regulated by SDF-1 in WM. As shown in Figure 5B, SDF-1 30 nM induced a rapid activation of pERK/MAPK at 1 and 3 minutes and activation of pAkt and pPKC at 3 and 5 minutes. In addition, pretreatment of WM cells with AMD3100 (20 μM) led to significant inhibition of pERK, pAkt, and pPKC, even in the presence of SDF-1 as shown in Figure 5C. We further observed that pERK and pAkt (S473) were inhibited in the CXCR4 knockdown cell lines, even in the presence of SDF-1 as shown in Figure 5D. To investigate whether the SDF-1–dependent migration and adhesion in WM are regulated by the PI3K/Akt and pERK/MAPK pathways, we performed immunoblotting using the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (25 μM for 15 minutes) or the MEK inhibitor PD098059 (20 μM for 20 minutes) and found that PD inhibits pERK, even in the presence of SDF-1, and LY29002 inhibits pAkt, even in the presence of SDF-1 (30 nM) as shown in Figure 5E. To assess whether these pathways are essential for migration induced by SDF-1 in WM, we performed a transwell migration assay using LY294002 (25 μM for 15 minutes, P < .05) and PD098059 (20 μM for 20 minutes, P = .01) and demonstrated significant inhibition of migration in response to SDF-1, indicating that these pathways are downstream of CXCR4 and regulate SDF-1– dependent migration as shown in Figure 5F.

CXCR4 and VLA-4 cointeract and regulate downstream P13K and ERK/MAPK pathways. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation using anti–VLA-4 antibody and blotting for CXCR4 antibody, showing that SDF-1 30 nm for 3 minutes induces coimmunoprecipitation of CXCR4 with VLA-4 indicating direct interaction of these 2 receptors. (B) Immunoblotting of BCWM.1 stimulated with SDF-1 30 nM for 1, 2, 3, and 5 minutes. SDF-1 induced activation of pERK and pAkt within 1 and 3 minutes, whereas PKC activation occurred at 3 to 5 minutes. Anti–β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) Immunoblotting of BCWM.1 with SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes and in the presence of AMD3100 20 μM (pretreated for 2 hours followed by SDF-1 activation at the last 3 minutes). AMD3100 inhibited pERK, pAkt, and pPKC activation, even in the presence of SDF-1. (D) Immunoblotting for pERK and pAkt using the mock-infected or CXCR4-knockdown BCWM.1 cell line showing that SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes does not significantly activate pERK and pAkt in the CXCR4-knockdown cell line. (E) Immunoblotting with BCWM.1 showing activation of pERK and pAkt by SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes, whereas the MEK inhibitor PD098059 20 μM (for 20 minutes) inhibited pERK activation but not pAkt, and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (for 15 minutes) 25 μM inhibited pAkt and pERK activation, in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes. (F) Migration assay of BCWM.1 in response to 30 nM SDF-1 using PD098059 20 μM for 20-minute pretreatment, or LY294002 25 μM for 15-minute pretreatment, showing that PD098059 and LY294002 inhibit migration of BCWM.1 in response to SDF-1. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .01, **P = .05).

CXCR4 and VLA-4 cointeract and regulate downstream P13K and ERK/MAPK pathways. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation using anti–VLA-4 antibody and blotting for CXCR4 antibody, showing that SDF-1 30 nm for 3 minutes induces coimmunoprecipitation of CXCR4 with VLA-4 indicating direct interaction of these 2 receptors. (B) Immunoblotting of BCWM.1 stimulated with SDF-1 30 nM for 1, 2, 3, and 5 minutes. SDF-1 induced activation of pERK and pAkt within 1 and 3 minutes, whereas PKC activation occurred at 3 to 5 minutes. Anti–β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) Immunoblotting of BCWM.1 with SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes and in the presence of AMD3100 20 μM (pretreated for 2 hours followed by SDF-1 activation at the last 3 minutes). AMD3100 inhibited pERK, pAkt, and pPKC activation, even in the presence of SDF-1. (D) Immunoblotting for pERK and pAkt using the mock-infected or CXCR4-knockdown BCWM.1 cell line showing that SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes does not significantly activate pERK and pAkt in the CXCR4-knockdown cell line. (E) Immunoblotting with BCWM.1 showing activation of pERK and pAkt by SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes, whereas the MEK inhibitor PD098059 20 μM (for 20 minutes) inhibited pERK activation but not pAkt, and the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (for 15 minutes) 25 μM inhibited pAkt and pERK activation, in the presence of SDF-1 30 nM for 3 minutes. (F) Migration assay of BCWM.1 in response to 30 nM SDF-1 using PD098059 20 μM for 20-minute pretreatment, or LY294002 25 μM for 15-minute pretreatment, showing that PD098059 and LY294002 inhibit migration of BCWM.1 in response to SDF-1. Data show an average of 3 independent experiments (*P = .01, **P = .05).

Discussion

WM is characterized by widespread involvement of the BM in all patients, indicating homing and adhesion of the malignant cells to specific niches in the BM, which provide a protective environment for the survival and proliferation of these cells.2 However, little is known about the mechanisms by which malignant WM cells home and adhere to BM niches. Chemokines and adhesion molecules regulate the specific trafficking of lymphocytes and leukocytes to target tissues.26 In this study, we first identified the expression of 13 CXCR and CCR chemokine receptors in primary WM cells and cell lines compared with normal B lymphocytes from the BM of healthy volunteers. We found high levels of CXCR4 expression and then focused our studies on this receptor and its ligand SDF-1, as this axis is an important regulator of homing of hematopoeitic stem cells and malignant B cells.10 Our data demonstrate that that SDF-1 is highly up-regulated in the BM of WM patients compared with normal controls. Our results also show that CXCR4 is functionally important for the regulation of migration of WM cells and that CXCR4 knockdown leads to significant inhibition of migration of these cells.

We further sought to determine the effect of AMD3100, a specific CXCR4 inhibitor, on the migration and adhesion of WM cells. AMD3100 is a specific CXCR4 inhibitor used in stem cell mobilization in clinical trials.27 Therefore, the use of this inhibitor in WM could lead to a rapid translation of these studies to clinical trials to prevent homing and dissemination of malignant cells in patients with WM. This inhibitor as well as a Gi protein inhibitor (PTX) led to a significant inhibition of migration to SDF-1 in WM cell lines, primary patient samples, and inhibited transendothelial migration of WM cells, even in the shear flow system. We then demonstrated that CXCR4 also regulates adhesion of WM cells to fibronectin, endothelial cells, and stromal cells. Most significantly, we demonstrated that inhibition of adhesion induced by AMD3100 leads to increased sensitivity of WM cells to inhibition of proliferation induced by bortezomib. These results indicate that AMD3100 can be used in future clinical trials to inhibit adhesion of WM cells and induce sensitivity to bortezomib. We then investigated the mechanisms by which CXCR4 regulates adhesion and migration in WM and showed that CXCR4 and VLA-4 directly interact in response to SDF-1, explaining the lack of additive effect of anti–VLA-4 antibody and AMD3100 on adhesion. In addition, we showed that SDF-1 induces Akt, ERK, and PKC activation downstream of CXCR4 and that inhibition of PI3K by LY294002 upstream of Akt and PKC and MEK inhibition by PD98059 leads to significant inhibition of migration. In summary, these studies delineate the role of CXCR4/SDF-1 in the process of migration, rolling, and adhesion in WM, and demonstrate that AMD3100 may be used in future clinical applications in the regulation of trafficking of WM cells and increasing sensitivity to therapeutic agents.

In conclusion, these studies demonstrate that the CXCR4/SDF-1 axis interacts with VLA-4 in regulating trafficking and adhesion of WM cells to the BM. CXCR4 regulates migration and transendothelial migration as well as adhesion to stromal cells and endothelial cells. These studies provide the framework to study inhibitors of CXCR4 or VLA-4 in regulating trafficking and dissemination of malignant cells in WM.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R21CA126119-01, the International Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia Foundation, ASH Scholar Award, and ASCO Young Investigator Award. I.M.G. is a Lymphoma Research Foundation Scholar.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: H.T.N., X.L., J.L., M.M., X.J., and J.R. performed the research; A.-S.M., A.K.A., A.R., F.A., A.S., N.B., and M.F. analyzed the data; H.T.N., X.L., R.S., and I.M.G. designed the studies; H.T.N., X.L., and I.M.G. wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: I.M.G. has received research grants from Keryx Biopharmaceuticals and Millennium Pharmaceuticals and is on the speaker bureaus of Millennium and Celgene. All other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Irene M. Ghobrial, Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney Street, Mayer 548A, Boston, MA, 02115; e-mail: irene_ghobrial@dfci.harvard.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal