Abstract

The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor stem cell leukemia gene (Scl) is a master regulator for hematopoiesis essential for hematopoietic specification and proper differentiation of the erythroid and megakaryocyte lineages. However, the critical downstream targets of Scl remain undefined. Here, we identified a novel Scl target gene, transcription factor myocyte enhancer factor 2 C (Mef2C) from Sclfl/fl fetal liver progenitor cell lines. Analysis of Mef2C−/− embryos showed that Mef2C, in contrast to Scl, is not essential for specification into primitive or definitive hematopoietic lineages. However, adult VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice exhibited platelet defects similar to those observed in Scl-deficient mice. The platelet counts were reduced, whereas platelet size was increased and the platelet shape and granularity were altered. Furthermore, megakaryopoiesis was severely impaired in vitro. Chromatin immunoprecipitation microarray hybridization analysis revealed that Mef2C is directly regulated by Scl in megakaryocytic cells, but not in erythroid cells. In addition, an Scl-independent requirement for Mef2C in B-lymphoid homeostasis was observed in Mef2C-deficient mice, characterized as severe age-dependent reduction of specific B-cell progenitor populations reminiscent of premature aging. In summary, this work identifies Mef2C as an integral member of hematopoietic transcription factors with distinct upstream regulatory mechanisms and functional requirements in megakaryocyte and B-lymphoid lineages.

Introduction

Hematopoiesis, the process of blood formation, secures a continuous supply of all blood cell types throughout embryogenesis and adult life.1 During development, hematopoiesis is segregated into distinct anatomic sites, which ensures rapid production of differentiated blood cells for the embryo's immediate needs, and the generation of definitive hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) that are required for life-long hematopoiesis.2 Homeostasis in the bone marrow is dependent on the faithful ability of HSCs to self-renew and to generate progenitor cells that undergo limited proliferation and give rise to terminally differentiated blood cells. These fate decisions are orchestrated by a network of transcription factors that govern stem cell– or lineage-specific gene expression programs required for proper development and function of blood cells.1,3

During embryogenesis, the hematopoietic program is established by the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor Scl/Tal1 (stem cell leukemia gene/T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia gene 1).4 In the absence of Scl, blood-specific genes fail to be activated, resulting in an arrest in blood development at the hemangioblast stage.5,6 As such, Scl knockout embryos die by E9.5.7,8 Surprisingly, despite Scl's pivotal role in the initiation of the hematopoietic program, Scl becomes dispensable for further development and function of HSCs shortly after hematopoietic specification.9,10 Yet, Scl is redeployed during erythroid and megakaryocytic development. In the erythroid lineage, Scl deficiency leads to inefficient erythropoiesis in both the fetal liver and bone marrow, and impaired erythroid differentiation in vitro.9-12 In the megakaryocytic lineage, loss of Scl in adult mice results in thrombocytopenia because of defects in megakaryocyte cytoplasmic maturation and platelet shedding.9,10,12,13 In addition, Scl-deficient progenitor cells are unable to generate megakaryocytes in vitro.9,10 Although the critical transcriptional target genes of Scl remain poorly defined, 2 membrane proteins, Band 4.2 and glycophorin A (GPA), have been nominated as Scl targets in erythroid cells,14,15 whereas NF-E2 and β1-tubulin were shown to be downstream of Scl in megakaryocytes.13 Rescue experiments with a mutated DNA-binding domain in the Scl gene showed that DNA-binding activity of Scl was dispensable for hematopoietic specification but required for proper erythroid and megakaryocyte differentiation.16 These results suggest that Scl uses different mechanisms for regulating at least a subset of target genes during hematopoietic specification vs differentiation to distinct lineages.

To understand how the same transcription factor regulates different developmental fates within the hematopoietic hierarchy, we sought to identify Scl target genes in different lineages. By performing gene expression analysis of progenitor cell lines that we derived from Sclfl/fl fetal livers, we identified Mef2C as a target gene of Scl during megakaryopoiesis. Analysis of conventional knockout (Mef2C−/−) and hematopoietic-specific conditional knockout (VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl) mouse models of Mef2C showed that Mef2C is neither essential for hematopoietic specification nor for establishment and maintenance of multilineage hematopoiesis. However, Mef2C-deficient mice exhibit thrombocytopenia and a defect in B-lymphopoiesis that is reminiscent of premature B-cell aging. Direct binding of Scl to Mef2C-regulatory elements in megakaryocytes and overlapping phenotypes in megakaryocyte/platelet development in both Scl and Mef2C conditional knockout mice imply that the Scl-Mef2C axis is used specifically to sustain proper platelet homeostasis. In contrast, in B cells, where Scl is not expressed, Mef2C is regulated by Scl-independent mechanisms. These results imply that Scl governs distinct transcriptional programs in different lineages and developmental stages.

Methods

Establishment of Hox11-immortalized Sclfl/fl progenitor lines

Sclfl/fl hematopoietic progenitor lines were generated from fetal liver progenitors from E12.5 Sclfl/fl embryos9 by immortalization with Hox11 retrovirus.17 Sclfl/fl progenitor cells were cultured with interleukin-3 (IL-3), and a clonal line containing cells with megakaryocyte morphology and acetylcholinesterase (AchE) activity was selected. The Sclfl/fl cell line was transduced with Cre-GFP retrovirus to generate the SclΔ/Δ line, and the SclΔ/Δ line was transduced with Scl retrovirus to reintroduce Scl expression (SclΔ/Δ+Scl line). Megakaryocyte differentiation was enhanced by adding thrombopoietin (TPO) for 5 days before harvesting the cells. Sections were analyzed on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornbury, NY). Images were captured using a Canon PC1089 (Canon, Lake Success, NY). RNA was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNEasy (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) kits. Differential gene expression between Sclfl/fl, SclΔ/Δ, and SclΔ/Δ + Scl cell lines was analyzed by Affymetrix MOE430_2 microarray (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) in the microarray core facility at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The microarray data have been deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus (Gekas et al, 2009) and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE14478 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc/GSE14478).

Gene expression analysis

Expression profiles were first-quantile normalized. A t test was performed to assess significant changes between the 3 cell lines. The following exclusion criteria were used to filter out nonsignificant genes: probe sets with no rescue—that is, with absolute value of (SclΔ/Δ+Scl-SclΔ/Δ)/ SclΔ/Δ < 0.5—and probes with an absolute t test value less than 1 were filtered out. The ratios between SclΔ/Δ and Sclfl/fl of all remaining probes were ranked in the 2 independent experiments (ratio 1 and ratio 2). Finally, all probes across both experiments were assessed by sorting by the mean rank (ratio 1 + ratio 2). All analyses were performed using Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Transcription binding motif analysis in the promoters of genes was carried out by scanning approximately 800 position weight matrices from the TRANSFAC database18 (http://www.gene-regulation.com/) along the promoters to identify the maximum log odds score for each matrix. Potential targets for each transcription factor were identified using various thresholds (top 10%, top 1%, and top 0.1% of all scores). The overlap between the targets of each transcription factor and the list of Scl target genes from the analysis described in this section was compared, and the significance of the overlap was measured using the hypergeometric distribution.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and microarray hybridization

L8057 cells were induced to differentiate with 50 nM phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 5 days, and mature megakaryocytes were sorted by size on a FACS Aria cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). A Hox11 immortalized proerythroblast cell line was used as control. Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed essentially as described,19 with a few modifications. Lysates corresponding to 200 000 sorted cells were immunoprecipitated with Scl/Tal-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or H3K9Ac antibodies (Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA). DNA was amplified, labeled, and hybridized onto a mouse promoter array (G4490A, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), and arrays were scanned (Agilent DNA Microarray scanner). Data analysis was performed using the Agilent Feature Extraction software (version 9.1.3.1) and ChIP Analytics software (version 1.2). Probe signals were normalized with Lowess normalization, and the datasets were normalized to generate mean values of 0 and variances of 1.

Mouse models

Scl−/− and Mef2C−/− embryos were obtained by timed matings of Scl+/− or Mef2C+/− mice.7,20 To generate VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice, VavCre+ mice (kindly provided by Dr Thomas Graf) were bred with Mef2Cfl/fl mice.21 To generate VavCre+Sclfl/fl mice, VavCre+ mice were bred with Sclfl/fl mice.22 Genotyping primers are: Scl-F AGC GCT GCT CTA TAG CCT TAG C and Scl-R CAC TAC TTT GGG TGT GAG GAC CAT (mutant band; 600 bp), Mef2C-3′arm CTA CTT GTC CCA AGA AAG GAC AGG AAA TGC AAA AAT GAG GCA and Mef2C-KO region GTG ATG ACC CAT ATG GGA TCT AGA AAT CAA GGT CCA GGG TCA G (wt band; 586 bp, flox band; 838 bp) and Mef2C-3′arm (listed in this section) with Mef2C-3′neo GTG GGC TCT ATG GCT TCT GAG GCG GAA AG (mutant band; 253 bp), Sclfl-F TGA AGA TGG CAC GGT CTT CTC Sclfl-R ATG GGA GAA AGG CAA GGC AG (wt band; 180 bp, flox band; 270 bp), Cre-F CGT ATA GCC GAA ATT GCC AG and Cre-R CAA AAC AGG TAG TTA TTC GG (Cre band; 200 bp). All mice were maintained according to the guidelines of the University of California–Los Angeles Animal Research Committee.

Analysis of peripheral blood counts

Blood was harvested from the retro-orbital sinus into Vacutainer tubes (BD Biosciences) and sent to the University of California–Los Angeles Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine laboratory for complete blood cytometry (CBC) analysis.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

Fetal tissues (yolk sac, caudal half, and heart) were harvested from Scl−/− and Scl+/− embryos and immediately homogenized in RLT buffer (RNEasy Mini Kit, QIAGEN) for RNA extraction. cDNA reaction was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol (Quantitect, QIAGEN), and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed by SYBR Green kit (QIAGEN). Primers used for quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR were: Mef2C-F agg tgt tgc tca agt aca ccg agt and Mef2C-R atc tca aag ctg gga ggt gga aca and, GAPDH-F AGT CTA TGA AGC AGT CAC CAA GAA C and GAPDH-R AGT TGA TTG GAG CTC TGT AGG TCT. Gapdh was used for internal normalization in each sample.

Flow cytometry

Rat anti–mouse monoclonal antibodies recognizing the following markers were used for flow cytometric analyses: c-kit, CD41, CD34, Sca1, Mac-1, Gr-1, B220, CD19, CD44, CD25, CD4, CD8, IgM, IgD, CD43, Il7Rα, CD24, CD31, CD9, CD71, Ter119, FcRγ (all from BD Biosciences) and CD45 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Dead cells were excluded with 7-amino-actinomycin D (BD Biosciences PharMingen, San Diego, CA). Cells were assayed on a BD LSRII flow cytometer, and data were analyzed with FlowJo software, version 8.7.1 (TreeStar, Ashland, OR). For the measurement of megakaryocyte DNA content, cells were incubated with DRAQ5 (Biostatus, Shepshed, United Kingdom) at 37°C for 5 minutes and immediately assessed via fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS).

Coculture on OP9 stroma

Fetal organ explants (1 embryo equivalent) were cocultured on OP9 stroma in 24-well plates in 1 mL α-minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 1% penicillin/streptomycin and supplemented with stem cell factor (SCF) (50 ng/mL), IL-3 (5 ng/mL), IL-6 (5 ng/mL), TPO (5 ng/mL), IL-7 (10 ng/mL), and Flt3 ligand (10 ng/mL) for 4 days. Half of the medium was replaced every other day. To assay B-lymphoid potential, half of the explant cultures were replated on fresh OP9 stroma supplemented with B-cell-promoting cytokines: IL-7 (100 ng/mL), SCF (50 ng/mL), and Flt3 ligand (40 ng/mL). All cytokines were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Colony-forming assays

Single-cell suspensions were obtained as previously described23 and plated on methylcellulose (MethoCult M3434) supplemented with TPO (5 ng/mL). Alternatively, tissues were cocultured on OP9 stroma for 4 days, as described under “Coculture on OP9 stroma.” before methylcellulose culture. Colonies were scored and harvested 7 days later. For B-cell differentiation, cells were cocultured on OP9 for 6 to 10 days, plated on B lymphoid–promoting methylcellulose cultures for 14 to 17 days, and analyzed by FACS as previously described.23 For megakaryocytic differentiation, 5 × 104 cells were plated in MethoCult (M3434 supplemented with 50 ng/mL TPO, or M3234 supplemented with IL-3 (10 ng/mL), IL-6 (20 ng/mL), IL-11 (50 ng/mL), and TPO (50 ng/mL) or MegaCult per the manufacturer's instructions. Colonies were scored and harvested for cytospins (3 × 105 cells) after 7 to 12 days. MethoCult and MegaCult were purchased from StemCell Technologies (Vancouver, BC).

AchE staining

Cytospins from fresh and culture-derived cells were stained for AchE activity as previously described.24 Slides were stained for approximately 6 hours, counterstained by Harris hematoxylin, air-dried overnight, and mounted with Vecta-Mount (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Sections were analyzed on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope. Images were captured using a Canon PC1089.

Mef2C rescue by retroviral transduction

Bone marrow c-kit+ progenitors were sorted from VavCreMef2Cfl/fl and VavCreSclfl/fl mice and their respective littermate controls. The progenitors (2 × 104 cells) were prestimulated for 12 hours in α-minimum essential medium (Invitrogen) containing 20% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories), SCF (50 ng/mL), IL-3 (5 ng/mL), IL-6 (5 ng/mL), TPO (50 ng/mL), IL-11 (50 ng/mL), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 8 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were spinoculated with Mef2C retroviral supernatant (MSCV-puro) containing 20% fetal calf serum, cytokines and supplements as described at 500g for 60 minutes at 37°C. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were plated in methylcellulose (MethoCult M3434) supplemented with TPO (50 ng/mL), IL-11 (50 ng/mL), and puromycin (2.5 μg/mL). Mock controls were treated the same with the exception of adding puromycin. After 7 to 10 days, megakaryocyte colonies were scored, harvested, cytospun (300 000 cells/slide), and stained for AchE activity.

Electron microscopy

Washed platelets were isolated as per standard protocol and fixed in 2% gluteraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline overnight. Platelets were processed in EPON resin per standard electron microscopy protocol. Ultrathin sections were cut and viewed in a JEOL 100CX transmission electron microscope (JEOL USA, Peabody, MA). Images were captured on a Gatan UltraScan 2k*2k camera (Gatan, Warrendale, PA), developed and scanned at 1200 dpi. Magnification was at 10 000×.

Results

Mef2C is a target gene of Scl during megakaryopoiesis

To define transcriptional targets of Scl in different cell types, we generated Sclfl/fl hematopoietic progenitor lines from E12.5 Sclfl/fl fetal liver cells by immortalization with the Hox11 retrovirus.17 A clonal line that contained cells with megakaryocyte morphology and AchE activity was selected (Figure 1A). To investigate which genes are downstream of Scl, an SclΔ/Δ cell line was generated by transduction of the parental line with a Cre-GFP retrovirus. To verify that the observed effects on gene expression and phenotype were directly related to loss of Scl, Scl expression in the SclΔ/Δ cell line was rescued with an Scl retrovirus (SclΔ/Δ+Scl cell line; Figure 1A). Deletion of the conditionally targeted Scl alleles resulted in an arrest in megakaryocyte differentiation as demonstrated by loss of AchE+ cells (Figure 1A), whereas rescue by Scl-expressing retrovirus generated AchE+ cells similar to the parental Sclfl/fl line (Figure 1A).

Microarray analysis of Sclfl/fl fetal liver progenitor cell lines identifies candidate target genes for Scl/Tal1. (A) Hematopoietic progenitor cell lines were generated from fetal livers of E12.5 Sclfl/fl embryos by immortalization with Hox11 retrovirus (Sclfl/fl parental cell line). Deletion of Scl gene was achieved by transduction with a Cre-GFP retroviral vector (SclΔ/Δ). Scl-deficienT cells exhibited impaired megakaryocytic maturation demonstrated by the loss of AchE activity. Reintroduction of Scl expression with an Scl retroviral vector rescued the megakaryocytic maturation defect (SclΔ/Δ+Scl). After 5 days of culture with TPO and IL-3, the cell lines were harvested and subjected to Affymetrix gene expression analysis to identify Scl-dependent genes. (Sections were analyzed on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope. Images were captured using a Canon PC1089. Magnification, ×40.) (B) Analysis of the top 50 genes that were down-regulated on loss of Scl reveals genes known to be involved in hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis, as well as unknown ESTs and cDNAs (i). Myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2C) was one of the genes whose expression was down-regulated in the absence of Scl, and rescued on reintroduction of Scl. (ii) The bar graph depicts the average expression of Mef2C across 3 different probes in one experiment.

Microarray analysis of Sclfl/fl fetal liver progenitor cell lines identifies candidate target genes for Scl/Tal1. (A) Hematopoietic progenitor cell lines were generated from fetal livers of E12.5 Sclfl/fl embryos by immortalization with Hox11 retrovirus (Sclfl/fl parental cell line). Deletion of Scl gene was achieved by transduction with a Cre-GFP retroviral vector (SclΔ/Δ). Scl-deficienT cells exhibited impaired megakaryocytic maturation demonstrated by the loss of AchE activity. Reintroduction of Scl expression with an Scl retroviral vector rescued the megakaryocytic maturation defect (SclΔ/Δ+Scl). After 5 days of culture with TPO and IL-3, the cell lines were harvested and subjected to Affymetrix gene expression analysis to identify Scl-dependent genes. (Sections were analyzed on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope. Images were captured using a Canon PC1089. Magnification, ×40.) (B) Analysis of the top 50 genes that were down-regulated on loss of Scl reveals genes known to be involved in hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis, as well as unknown ESTs and cDNAs (i). Myocyte enhancer factor 2C (Mef2C) was one of the genes whose expression was down-regulated in the absence of Scl, and rescued on reintroduction of Scl. (ii) The bar graph depicts the average expression of Mef2C across 3 different probes in one experiment.

To elucidate downstream targets of Scl in the megakaryocytic lineage, the cell lines were cultured in the presence of IL-3 and TPO for 5 days, and differential gene expression between Sclfl/fl, SclΔ/Δ, and SclΔ/Δ + Scl cell lines was analyzed by Affymetrix microarray (Figure 1A). To identify the genes that demonstrated a significant change in expression in 2 independent experiments, several exclusion criteria were enforced (“Gene expression analysis”). These criteria defined 193 genes that were down-regulated and 87 that were up-regulated in the absence of Scl. The top 50 down-regulated genes included transcription factors and other genes known to be expressed in megakaryocytes, erythrocytes, or other hematopoietic/vascular cells, as well as miscellaneous genes and as yet unknown expressed sequence tags (ESTs)/cDNAs not previously linked to blood development (Figure 1Bi). DNA-binding motif analysis of the promoter regions of these genes revealed an enrichment of a bHLH-specific E-Box (CAGGTG), suggesting that bHLH factors may directly regulate many of these genes. One of the top down-regulated genes was the transcription factor Mef2C, which has been widely studied because of its requirement in muscle, heart, and vascular development19,25,26 but has not been associated with megakaryocyte or erythroid development. Mef2C expression was reduced to 22% (an average over 3 probes) in the SclΔ/Δ line and rescued to 156% of the parental line in SclΔ/Δ + Scl line (Figure 1Bii).

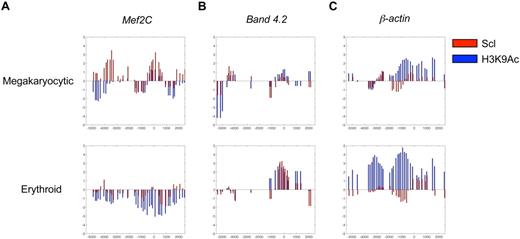

As the Hox11 immortalized progenitor line exhibits characteristics of both megakaryocytic and erythroid cells, Mef2C expression was compared between 2 cell lines that consist exclusively of erythroid (Hox11 immortalized proerythroblast cell line) or megakaryocytic cells (L8057 megakaryoblast cell line). Real-time PCR analysis indicated that Mef2C was expressed only in megakaryocytic, but not in erythroid, cells (data not shown). To define whether Scl regulates Mef2C transcription directly, binding of Scl onto the promoter region of the Mef2C gene was assessed in megakaryocyte and proerythroblast cell lines by chromatin immunoprecipitation microarray hybridization (ChIP-chip). Binding of Scl/Tal-1 was assessed in conjunction with histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation (H3K9Ac), a chromatin modification associated with gene expression. These analyses revealed that Mef2C belongs to the top 1.5% of genes bound by Scl in megakaryocytes. Specifically, Scl binds at the transcriptional start site of the Mef2C promoter (z-score = 3.3; Figure 2A) and to an upstream region (z-score = 3.5, P < 10−60). Furthermore, Scl binding is accompanied by H3K9 acetylation at the transcriptional start site. In contrast, in proerythroblasts where Mef2C is not expressed, the Mef2C promoter was not bound by Scl, and no significant H3K9 acetylation was observed (Figure 2A). However, the proerythroblast cell line exhibited binding of Scl and H3K9 acetylation at the promoter of the erythroid-specific Scl target gene Band 4.2 (Figure 2B), whereas no significant binding of Scl or H3K9Ac was associated with the Band 4.2 promoter in the megakaryocytic cell line (Figure 2B). As expected, H3K9Ac is enriched at the promoter of the housekeeping gene β-actin in both megakaryocytic and erythroid cell lines, whereas Scl was not significantly bound to the β-actin promoter in either cell type (Figure 2C). These data imply that Mef2C is selectively regulated by Scl during megakaryopoiesis.

ChIP-chip analysis defines direct binding of Scl to Mef2C gene in megakaryocytic cells. ChIP-chip analysis was performed to determine direct target genes for Scl in megakaryocytic and erythroid cell lines. (A) Mef2C promoter is bound by Scl (red bars) at the transcriptional start site (0) in the L8057 megakaryoblast cell line, but not in the erythroblast cell line (Hox11 immortalized cell line). Scl binding is accompanied by acetylation on histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9Ac; blue bars) at the transcriptional start site. (B) Band 4.2, a known Scl target gene in erythroid cells, is bound by Scl in the erythroid cell line, whereas no significant signal was observed in the megakaryocytic cell line. (C) The housekeeping gene β-actin is acetylated in both megakaryocytic and erythroid cells, whereas no significant binding of Scl is observed in either of the cell lines.

ChIP-chip analysis defines direct binding of Scl to Mef2C gene in megakaryocytic cells. ChIP-chip analysis was performed to determine direct target genes for Scl in megakaryocytic and erythroid cell lines. (A) Mef2C promoter is bound by Scl (red bars) at the transcriptional start site (0) in the L8057 megakaryoblast cell line, but not in the erythroblast cell line (Hox11 immortalized cell line). Scl binding is accompanied by acetylation on histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9Ac; blue bars) at the transcriptional start site. (B) Band 4.2, a known Scl target gene in erythroid cells, is bound by Scl in the erythroid cell line, whereas no significant signal was observed in the megakaryocytic cell line. (C) The housekeeping gene β-actin is acetylated in both megakaryocytic and erythroid cells, whereas no significant binding of Scl is observed in either of the cell lines.

Specification into primitive and definitive hematopoietic lineages occurs in the absence of Mef2C

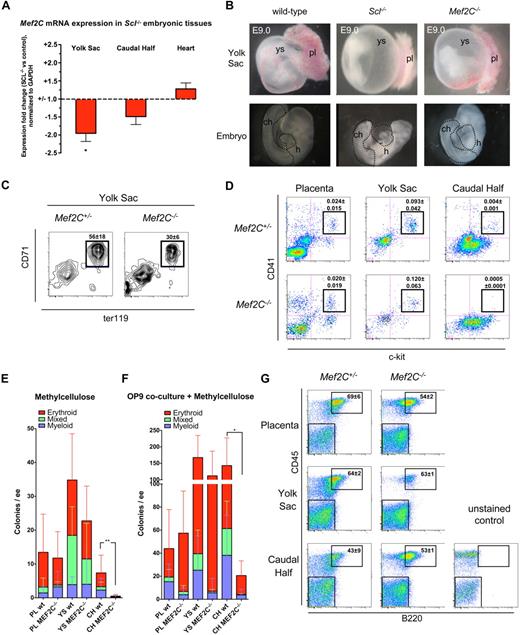

To investigate whether Mef2C is also downstream of Scl during embryonic development in vivo, Mef2C mRNA expression was analyzed in E9.0 Scl−/− tissues by quantitative reverse-transcribed PCR. Expression of Mef2C was reduced approximately 2-fold in Scl−/− yolk sac and approximately 1.5-fold in the caudal half of the embryo, which harbors precursors for both hematopoietic/vascular cells and somites (Figure 3A).27,28 Expression of Mef2C in Scl−/− heart was not significantly altered (Figure 3A). We next asked whether Mef2C−/− embryos recapitulate the profound hematopoietic defects observed in Scl−/− embryos.7,29 Mef2C−/− embryos die by E9.5, at the same time as Scl−/− embryos, with severe cardiac and vascular defects.20,25,26 Gross anatomic analysis of E9.0 embryos showed that both Scl−/− and Mef2C−/− yolk sacs lack the fine, organized vasculature observed in wild-type yolk sacs (Figure 3B).30 However, in contrast to Scl−/− yolk sacs, which were completely devoid of red blood cells, Mef2C−/− yolk sacs harbored pools of blood within the poorly remodeled vasculature (Figure 3B). Overall, Mef2C−/− embryos appeared paler than wild-type embryos, although blood could occasionally be seen in the tail and in the heart (Figure 3B). The hearts of both Scl−/− and Mef2C−/− embryos frequently displayed pericardial effusion indicative of reduced cardiac output.

Analysis of Mef2C−/− embryos documents that specification into primitive and definitive hematopoietic lineages occurs in the absence of Mef2C. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis reveals a reduction of Mef2C expression in hematopoietic tissues of Scl−/− mice, but not in the heart. *P < .05; N = 5. (B) Gross morphologic comparison of E9.0 Scl−/− and Mef2C−/− yolk sac and embryos documents that the complete hematopoietic specification defect in Scl−/− embryos is not recapitulated in Mef2C−/− embryos. Yet the vascular network in Mef2C−/− yolk sacs is poorly developed. pl indicates placenta; ch, caudal half; h, heart. Dotted lines in the embryo proper indicate dissected tissues. (C) FACS analysis of E9.0 yolk sac cells showed that CD71+Ter119+ primitive erythroid cells are generated in the absence of Mef2C, albeit at reduced levels compared with Mef2C+/− controls. Values represent mean frequency plus or minus SD (N = 4). (D) FACS analysis of ckit+CD41+ nascent hematopoietic progenitors demonstrated a striking reduction of progenitors in the caudal half of the embryo proper but not in the placenta or yolk sac. Values represent mean frequency plus or minus SD (Mef2C+/−; N = 4, Mef2C−/−; N = 5). (E) In agreement with the loss of ckit+CD41+ cells shown by FACS, direct plating of dissociated hematopoietic tissues on methylcellulose showed a severe reduction in numbers of clonogenic progenitors per embryo equivalent (ee) in Mef2C−/− caudal half (CH). As expected, colony formation in placenta (PL) and yolk sac (YS) was unaffected. **P < .01 of total colony numbers. (F) Coculture on OP9 stroma before plating on methylcellulose shows that the ability to generate hematopoietic colonies from the Mef2C−/− caudal half was partially rescued. As expected, placenta and yolk sac hematopoietic potential remained comparable with controls. *P < .05 of total colony numbers. (G) FACS analysis of B-lymphoid potential after coculture on OP9 stroma and methylcellulose documents that all hematopoietic tissues in Mef2C−/− embryos possess B-lymphoid potential. Numbers in FACS plots indicate the fraction of B220+ plus or minus SD (n = 3) cells within the CD45 hematopoietic gate.

Analysis of Mef2C−/− embryos documents that specification into primitive and definitive hematopoietic lineages occurs in the absence of Mef2C. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis reveals a reduction of Mef2C expression in hematopoietic tissues of Scl−/− mice, but not in the heart. *P < .05; N = 5. (B) Gross morphologic comparison of E9.0 Scl−/− and Mef2C−/− yolk sac and embryos documents that the complete hematopoietic specification defect in Scl−/− embryos is not recapitulated in Mef2C−/− embryos. Yet the vascular network in Mef2C−/− yolk sacs is poorly developed. pl indicates placenta; ch, caudal half; h, heart. Dotted lines in the embryo proper indicate dissected tissues. (C) FACS analysis of E9.0 yolk sac cells showed that CD71+Ter119+ primitive erythroid cells are generated in the absence of Mef2C, albeit at reduced levels compared with Mef2C+/− controls. Values represent mean frequency plus or minus SD (N = 4). (D) FACS analysis of ckit+CD41+ nascent hematopoietic progenitors demonstrated a striking reduction of progenitors in the caudal half of the embryo proper but not in the placenta or yolk sac. Values represent mean frequency plus or minus SD (Mef2C+/−; N = 4, Mef2C−/−; N = 5). (E) In agreement with the loss of ckit+CD41+ cells shown by FACS, direct plating of dissociated hematopoietic tissues on methylcellulose showed a severe reduction in numbers of clonogenic progenitors per embryo equivalent (ee) in Mef2C−/− caudal half (CH). As expected, colony formation in placenta (PL) and yolk sac (YS) was unaffected. **P < .01 of total colony numbers. (F) Coculture on OP9 stroma before plating on methylcellulose shows that the ability to generate hematopoietic colonies from the Mef2C−/− caudal half was partially rescued. As expected, placenta and yolk sac hematopoietic potential remained comparable with controls. *P < .05 of total colony numbers. (G) FACS analysis of B-lymphoid potential after coculture on OP9 stroma and methylcellulose documents that all hematopoietic tissues in Mef2C−/− embryos possess B-lymphoid potential. Numbers in FACS plots indicate the fraction of B220+ plus or minus SD (n = 3) cells within the CD45 hematopoietic gate.

Analysis of primitive erythropoiesis by FACS confirmed that CD71+Ter119+ erythroblasts were present in Mef2C−/− yolk sac, albeit at reduced levels (Figure 3C). To investigate whether Mef2C is required for the initiation of definitive hematopoiesis, fetal hematopoietic tissues from E8.75 to E9.75 embryos (somite pair range; Mef2C−/−: 13-26; wild-type: 13-30) were studied. First, yolk sac, caudal half of the embryo, and placenta were analyzed by FACS for expression of c-kit and CD41, which are known markers of early definitive hematopoietic progenitors.9,23 Interestingly, although c-kit+CD41+ progenitors were abundant in the placenta and yolk sac of Mef2C−/− embryos (Figure 3D), they were severely reduced in the caudal half of the embryo (Figure 3D). To functionally assess hematopoietic potential in the different sites, cells from each organ were plated on methylcellulose colony assay. In agreement with the FACS analysis, definitive clonogenic progenitors with myeloid, erythroid, or mixed-lineage potential were present at levels comparable with controls in the placenta and yolk sac of Mef2C−/− embryos (Figure 3E), whereas only very rare hematopoietic progenitors were found in the caudal half (Figure 3E).

To assess whether the poor capacity to generate hematopoietic progenitors in Mef2C−/−embryo proper was the result of a cell-intrinsic requirement for Mef2C in hematopoietic cells in this region, cell suspensions were first cocultured on a supportive OP9-stroma for 4 days before being transferred to methylcellulose, as shown earlier.23 Interestingly, the ability to generate definitive hematopoietic progenitors in the caudal half of the Mef2C−/− embryos was partially rescued after OP9 coculture, indicating that there is no absolute cell-intrinsic block in specification into definitive progenitors in the embryo proper. As expected, hematopoietic potential in Mef2C−/− placenta and yolk sac was again comparable with controls (Figure 3F). When cells from the OP9 cocultures were plated in methylcellulose cultures supportive of B-lymphoid differentiation, B220+ B cells were produced from all Mef2C−/− hematopoietic tissues (Figure 3G). Together, these data demonstrate that Mef2C is not essential for generating hematopoietic progenitors with primitive erythroid, multilineage myeloerythroid, or B-lymphoid potential, although loss of Mef2C does affect definitive hematopoiesis specifically in the embryo proper because of yet undefined mechanisms.

Mef2C is required for proper development of megakaryocytes and platelets

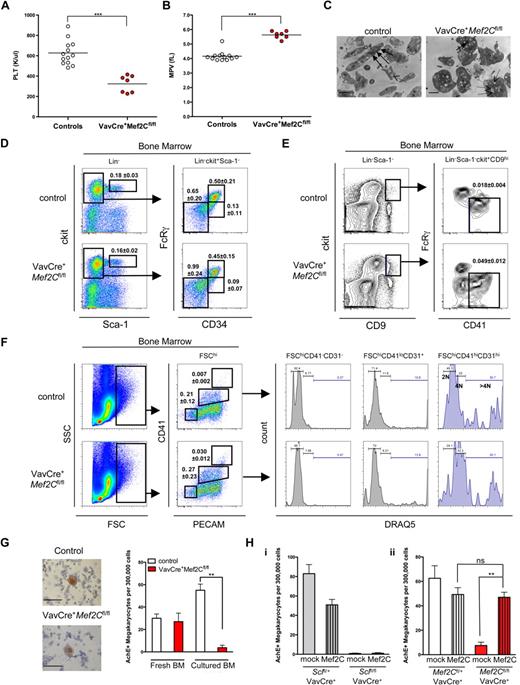

As Mef2C−/− mice die in utero, analysis of a potential role of Mef2C in postnatal hematopoiesis using this model was precluded. To bypass the embryonic lethality, we used a conditionally targeted Mef2Cfl/fl strain21 and crossed it with a hematopoietic cell-specific VavCre strain that deactivates Mef2C shortly after the emergence of HSCs.31 Despite the complete loss of Mef2C in the hematopoietic compartment (as verified by PCR for the floxed and excised alleles, data not shown), VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice survived into adulthood (> 1.5 years), demonstrating that loss of Mef2C during fetal or adult hematopoiesis does not result in profound hematopoietic failure. Concordantly, CBC analysis of adult VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mouse peripheral blood showed that most blood parameters, including red and white blood cell counts and hemoglobin level, were largely unperturbed (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). The only consistent abnormality was observed in the platelet compartment. All VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice analyzed displayed thrombocytopenia, characterized by an average 2-fold reduction in platelet counts (young mice, 1-3 months, 53% of controls; and older mice, 6-12 months, 46% of controls; Figure 4A and data not shown) and an increased mean platelet volume (Figure 4B). To define the defect in VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl platelets at the ultrastructural level, electron microscopy was performed. Strikingly, VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl platelets exhibited loss of elongated forms, remaining more spherical in shape. Furthermore, Mef2C-deficient platelets demonstrated a reduction in α-granules, whereas the number of depleted granules was increased (Figure 4C). These structural defects are very similar to those observed in Scl-deficient mice.13

Deletion of Mef2C in the hematopoietic system reveals a requirement of Mef2C for proper megakaryocyte/platelet development. (A,B) CBC analysis of peripheral blood showed that VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice exhibit marked thrombocytopenia and increased platelet size. Circles indicate analysis of individual mice. PLT indicates platelet count; MPV, mean platelet volume. ***P < .001. (C) Electron microscopy imaging of platelets reveals severe ultrastructural defects of Mef2C-deficient platelets, including enlarged size and loss of elongated form. In addition, Mef2C-deficient platelets demonstrated a loss of α-granules (→) and an increase in depleted granules (dashed arrows). (Images were captured on a Gatan UltraScan 2k*2k camera, developed and scanned at 1200 dpi. Magnification was ×10 000.) Scale bar represents 1 μm. (D) FACS analysis of the HSC/progenitor compartment shows that Mef2C-deficient mice maintain normal phenotypic frequency of HSCs (Lin−Sca-1hickithi), and CMP and granulocyte macrophage (GMP) progenitors. A slight increase in the frequency of myelo-erythroid progenitors (MEP) was observed. (E) FACS analysis documents a slight increase of committed unilineage megakaryocytic progenitors (CFU-Mk) in Mef2C-deficient mice. (F) Analysis of the megakaryocyte compartment revealed comparable frequency of immature megakaryocytes (FSChiCD41loCD31+) and a slight increase in the frequency of mature megakaryocytes (FSChiCD41+CD31+) in Mef2C-deficient mice. Assessment of ploidy using DRAQ5 showed that Mef2C-deficient immature and mature megakaryocytes are capable of endomitosis (> 4N). FSChiCD41−CD31− cells are shown as 2N controls. (G) AchE staining of bone marrow cytospins documents the presence of AchE+ megakaryocytes in the bone marrow of Mef2C-deficient mice. (Sections were analyzed on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope. Images were captured using a Canon PC1089. Magnification, ×20.) However, after in vitro culture, VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl bone marrow (BM) progenitors displayed a significantly impaired ability to generate AchE+ megakaryocytes compared with controls. Bars represent mean plus or minus SD; N = 3. (H) AchE staining of in vitro bone marrow cultures with (Mef2C) or without (mock) transduction with Mef2C retroviral vector shows that Mef2C does not rescue megakaryopoiesis in VavCre+Sclfl/fl bone marrow cultures (i), whereas it does rescue megakaryopoiesis in VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl bone marrow (ii). Bars indicate mean plus or minus SD, n = 4 to 6. **P < .01. ns indicates not significant.

Deletion of Mef2C in the hematopoietic system reveals a requirement of Mef2C for proper megakaryocyte/platelet development. (A,B) CBC analysis of peripheral blood showed that VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice exhibit marked thrombocytopenia and increased platelet size. Circles indicate analysis of individual mice. PLT indicates platelet count; MPV, mean platelet volume. ***P < .001. (C) Electron microscopy imaging of platelets reveals severe ultrastructural defects of Mef2C-deficient platelets, including enlarged size and loss of elongated form. In addition, Mef2C-deficient platelets demonstrated a loss of α-granules (→) and an increase in depleted granules (dashed arrows). (Images were captured on a Gatan UltraScan 2k*2k camera, developed and scanned at 1200 dpi. Magnification was ×10 000.) Scale bar represents 1 μm. (D) FACS analysis of the HSC/progenitor compartment shows that Mef2C-deficient mice maintain normal phenotypic frequency of HSCs (Lin−Sca-1hickithi), and CMP and granulocyte macrophage (GMP) progenitors. A slight increase in the frequency of myelo-erythroid progenitors (MEP) was observed. (E) FACS analysis documents a slight increase of committed unilineage megakaryocytic progenitors (CFU-Mk) in Mef2C-deficient mice. (F) Analysis of the megakaryocyte compartment revealed comparable frequency of immature megakaryocytes (FSChiCD41loCD31+) and a slight increase in the frequency of mature megakaryocytes (FSChiCD41+CD31+) in Mef2C-deficient mice. Assessment of ploidy using DRAQ5 showed that Mef2C-deficient immature and mature megakaryocytes are capable of endomitosis (> 4N). FSChiCD41−CD31− cells are shown as 2N controls. (G) AchE staining of bone marrow cytospins documents the presence of AchE+ megakaryocytes in the bone marrow of Mef2C-deficient mice. (Sections were analyzed on a Zeiss Axiovert 40 CFL microscope. Images were captured using a Canon PC1089. Magnification, ×20.) However, after in vitro culture, VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl bone marrow (BM) progenitors displayed a significantly impaired ability to generate AchE+ megakaryocytes compared with controls. Bars represent mean plus or minus SD; N = 3. (H) AchE staining of in vitro bone marrow cultures with (Mef2C) or without (mock) transduction with Mef2C retroviral vector shows that Mef2C does not rescue megakaryopoiesis in VavCre+Sclfl/fl bone marrow cultures (i), whereas it does rescue megakaryopoiesis in VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl bone marrow (ii). Bars indicate mean plus or minus SD, n = 4 to 6. **P < .01. ns indicates not significant.

To define at which stage Mef2C is required for platelet development, megakaryopoiesis was analyzed in the bone marrow of VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice. Frequencies of phenotypic HSCs (Lin−sca-1hickithi) were unaffected (Figure 4D), consistent with the finding that all major hematopoietic lineages were present. This was also the case for common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; Lin−ckitlosca-1−FcRγloCD34+). The frequency of MEPs (Lin−ckitlosca-1−FcRγloCD34−) and megakaryocyte-specific CFU-Mk progenitors (Lin−sca-1−ckit+CD9+FcRγlo/−CD41+) were slightly increased (Figure 4D,E). Furthermore, there was an increased frequency of phenotypically mature megakaryocytes (FSChiCD41hiCD31hi), whereas immature megakaryocytes (FSChiCD41loCD31+) were present at similar levels compared with controls (Figure 4F). These data indicate that the reduced platelet count in Mef2C-deficient mice cannot be explained by an impaired commitment to the megakaryocyte fate. To assess the maturation status of megakaryocytes, the DNA content was analyzed by FACS through incorporation of DRAQ5 DNA dye. Both FSChiCD41loCD31+ and FSChiCD41hiCD31hi megakaryocytes in VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl bone marrow displayed similar levels of ploidy compared with controls (Figure 4F), indicating that endomitosis, a hallmark of megakaryocyte maturation, is not dependent on Mef2C.

To further define how Mef2C deficiency affects platelet development, we tested the ability of Mef2C-deficient bone marrow to generate megakaryocytes and proplatelets in vitro. Strikingly, in contrast to control bone marrow, where proplatelet formation was frequently observed, no megakaryocyte colonies with characteristic proplatelet formation were observed in Mef2C-deficient bone marrow cultures (data not shown). To further assess megakaryocyte differentiation potential of Mef2C-deficient progenitors, cells from both fresh and cultured bone marrow were stained for AchE activity. Remarkably, in contrast to fresh bone marrow where abundant AchE+ megakaryocytes were observed in both control and VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl, only rare AchE+ cells were generated by the VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl bone marrow (Figure 4G). The discrepancy between the abundance of megakaryocytes in the bone marrow and the inability of Mef2C-deficient megakaryocyte precursors to generate AchE+ megakaryocytes in culture suggests that Mef2C affects a yet unknown pathway required in megakaryopoiesis in vitro, whereas alternative pathways may compensate for this defect in vivo.

Because we had identified Mef2C as a target gene for Scl in megakaryocytes and the megakaryocyte/platelet phenotypes were strikingly similar in Scl and Mef2C-deficient mice, we asked whether induction of Mef2C expression is sufficient to rescue the megakaryocyte/platelet defect observed in Scl conditional knockout mice. However, no rescue in generating AchE+ megakaryocytes from Scl-deficient bone marrow progenitors was observed when transduced with Mef2C retrovirus (Figure 4Hi). As expected, overexpression of Mef2C in Mef2C-deficient bone marrow cells resulted in a rescue of megakaryocyte differentiation in vitro (Figure 4Hii), validating the Mef2C overexpression system. Together, these data indicate that the requirement of Scl in megakaryopoiesis extends beyond induction of Mef2C expression.

Mef2C is required for bone marrow B lymphopoiesis

Although the leukocyte counts appeared grossly normal in VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice, we noted a slight shift in the relative ratios of lymphocytes and neutrophils in older mice (Table S1). We therefore assessed whether Mef2C is required for any specific lineage within the leukocyte compartment by performing FACS analysis of peripheral blood. These analyses confirmed a slight increase of Gr1+Mac1+ neutrophils in 6- to 12-month-old VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice (Figure S1A). Furthermore, although the frequencies of mature T cells were not significantly altered, both young and old Mef2C-deficient mice exhibited a decrease in peripheral blood B220+IgM+ B cells (Figure S1B,C). Interestingly, this defect was not accompanied with a decrease in mature IgM+ B cells in the spleen (Figure S1D).

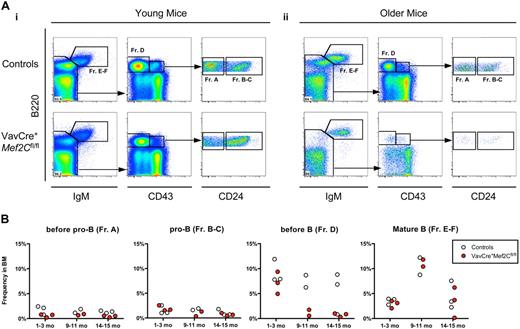

To investigate the defect in B lymphopoiesis further, we performed FACS analysis of bone marrow B-cell progenitors in both young and older mice by analyzing specific stages of B-cell development that have been defined by specific antigenic expression and immunoglobulin rearrangement status.32,33 The CLP compartment was unaffected in the bone marrow of both young and older VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice analyzed (data not shown). However, both young and older Mef2C-deficient mice exhibited a slight reduction in the frequency of pre-pro-B cells (Figure 5A,B, Fr. A). Furthermore, older VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl mice exhibited a severe reduction of the pre–B-cell compartment (Fr. D) already by 9 to 10 months of age, in stark contrast to their age-matched littermate controls (Figure 5Aii,B). Even so, the frequency of mature IgM+ B cells (Fr. E-F) was not altered compared with age-matched controls, regardless of age (Figure 5). These defects are highly similar to those observed during physiologic B-cell aging, which normally starts much later, during the second year of life. Taken together, these data indicate a requirement for Mef2C in maintaining bone marrow B-cell homeostasis, whereas B-cell differentiation and peripheral maintenance are independent of Mef2C.

Loss of Mef2C in hematopoietic cells results in impaired B-cell homeostasis similar to premature B-cell aging. (A) FACS analyses of frequencies of B-cell subsets in bone marrow of VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl and age-matched littermate control mice, for expression of B220, IgM, CD43, and CD24: representative examples of (i) young (1 month) and (ii) older (15 months) mice. Frequency of mature B220+IgM+ B cells (Fr. E-F) was not significantly altered regardless of age. Subgating on IgM− cells visualizes pre-B (Fr. D) and pro-B (Fr. B-C) populations. Strikingly, older, but not young, mice exhibited severe reductions of pre-B cells. Subgating on B220+CD43+ cells visualizes pre-pro-B (Fr. A) and pro-B cells. Of note, a slight reduction in the frequency of pre-pro-B cells was noted in both young and older mice. (B) Summary of all mice analyzed. Circles indicate analysis of individual young (1-2 months) and older (9-10 and 14-15 months) mice, and values represent frequency in whole BM.

Loss of Mef2C in hematopoietic cells results in impaired B-cell homeostasis similar to premature B-cell aging. (A) FACS analyses of frequencies of B-cell subsets in bone marrow of VavCre+Mef2Cfl/fl and age-matched littermate control mice, for expression of B220, IgM, CD43, and CD24: representative examples of (i) young (1 month) and (ii) older (15 months) mice. Frequency of mature B220+IgM+ B cells (Fr. E-F) was not significantly altered regardless of age. Subgating on IgM− cells visualizes pre-B (Fr. D) and pro-B (Fr. B-C) populations. Strikingly, older, but not young, mice exhibited severe reductions of pre-B cells. Subgating on B220+CD43+ cells visualizes pre-pro-B (Fr. A) and pro-B cells. Of note, a slight reduction in the frequency of pre-pro-B cells was noted in both young and older mice. (B) Summary of all mice analyzed. Circles indicate analysis of individual young (1-2 months) and older (9-10 and 14-15 months) mice, and values represent frequency in whole BM.

Discussion

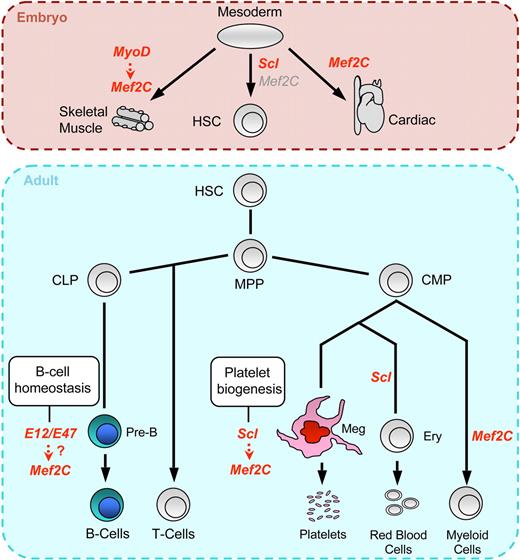

Despite the importance of Scl for hematopoietic specification and megakaryocyte/platelet and red cell development, its critical target genes remain poorly defined. Our results nominate Mef2C as a novel physiologically relevant direct target gene of Scl/Tal1 in megakaryopoiesis and platelet biogenesis (Figure 6). In addition, our data reveal a previously unappreciated role of Mef2C in primary B lymphopoiesis. The redeployment of Mef2C in different blood cell compartments highlights the dynamic expression patterns observed also for other key regulators of hematopoiesis, including Scl, which are used parsimoniously for differentiation and maintenance of distinct hematopoietic lineages.1

Proposed model of Mef2C regulation and function in hematopoiesis. Unlike Scl, which is absolutely required for the specification of mesoderm to blood and emergence of HSCs, Mef2C is not essential for hematopoietic specification, although it remains unclear why definitive hematopoiesis specifically in the embryo proper is impaired. It is plausible that the defects in vascular, muscle, and cardiac differentiation observed in Mef2C−/− embryos may indirectly affect hematopoiesis in the embryo proper. In the adult, we discovered novel requirements for Mef2C in 2 hematopoietic lineages. Our data indicate that, in the megakaryocytic lineage, Mef2C is a direct target gene of Scl and, as Scl, is required for proper megakaryopoiesis and platelet biogenesis. In contrast, although Scl is required for erythroid differentiation, Scl does not activate Mef2C in erythroid cells. In B cells, where Scl is not expressed, Mef2C probably acts downstream of other bHLH factors (eg, E12/E47) to counteract B-lymphocyte aging, especially within the pre–B-cell fraction. Finally, Mef2C was recently shown to be expressed in myeloid cells where it acts to modulate myeloid cell fates.44 Text in red indicates expression and cell-intrinsic functional requirement in the specific lineage, whereas gray text indicates expression in tissues in which cell-intrinsic functional requirement of Mef2C in hematopoietic cells has not been documented. HSC indicates hematopoietic stem cell; MPP, multipotent progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; Meg, megakaryocyte; and Ery, erythroid progenitor.

Proposed model of Mef2C regulation and function in hematopoiesis. Unlike Scl, which is absolutely required for the specification of mesoderm to blood and emergence of HSCs, Mef2C is not essential for hematopoietic specification, although it remains unclear why definitive hematopoiesis specifically in the embryo proper is impaired. It is plausible that the defects in vascular, muscle, and cardiac differentiation observed in Mef2C−/− embryos may indirectly affect hematopoiesis in the embryo proper. In the adult, we discovered novel requirements for Mef2C in 2 hematopoietic lineages. Our data indicate that, in the megakaryocytic lineage, Mef2C is a direct target gene of Scl and, as Scl, is required for proper megakaryopoiesis and platelet biogenesis. In contrast, although Scl is required for erythroid differentiation, Scl does not activate Mef2C in erythroid cells. In B cells, where Scl is not expressed, Mef2C probably acts downstream of other bHLH factors (eg, E12/E47) to counteract B-lymphocyte aging, especially within the pre–B-cell fraction. Finally, Mef2C was recently shown to be expressed in myeloid cells where it acts to modulate myeloid cell fates.44 Text in red indicates expression and cell-intrinsic functional requirement in the specific lineage, whereas gray text indicates expression in tissues in which cell-intrinsic functional requirement of Mef2C in hematopoietic cells has not been documented. HSC indicates hematopoietic stem cell; MPP, multipotent progenitor; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; Meg, megakaryocyte; and Ery, erythroid progenitor.

Although Mef2C−/− and Scl−/− embryos die at the same developmental age, our data show that Mef2C is not required for hematopoietic specification and therefore is not responsible for the defects in embryonic hematopoiesis observed in Scl−/− embryos. However, we noted a defect in the hematopoietic progenitor compartment of the embryo proper that could be partially rescued by in vitro culture on supportive stroma. As Mef2C has well-described roles in endothelial, cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle development, loss of Mef2C in these tissues could negatively impact microenvironment that supports definitive hematopoiesis in the embryo proper.

Our finding that Scl binds to the Mef2C locus in megakaryocytic, but not erythroid, cells implies that Scl uses distinct target genes in different cell types to regulate differentiation. However, further studies are needed to define how Scl preferentially binds one target gene over another in distinct cell types. Epigenetic modifications and unique binding partners in the transcriptional complex probably influence such decisions. Interestingly, the impairment in platelet development in Mef2C-deficient animals is strikingly similar to the defects observed in Scl-deficient mice; both conditional knockout animals display a reduction in platelet counts, an increase in mean platelet volume, a loss in elongated forms, and a reduction in platelet granules.13 In vitro, loss of Mef2C, like Scl, drastically impaired the potential of bone marrow progenitors to differentiate into megakaryocytes.9,10,12,13 Furthermore, a recent gene expression study revealed up-regulation of MEF2C after SCL expression in human CD34+ progenitors undergoing megakaryocytic differentiation.34 These data imply that the Scl-Mef2C axis plays a crucial role in megakaryocyte/platelet development. However, despite the similarity of the megakaryocyte/platelet phenotypes in Scl- and Mef2C-deficient mice, ectopic Mef2C expression could not rescue defective megakaryopoiesis in Scl-deficient bone marrow progenitors. Thus, Scl may be required to activate additional megakaryocyte-specific genes that are crucial at least for generating megakaryocytes in vitro. Alternatively, Scl and Mef2C may act together, as has been previously suggested for myogenic bHLH factors and Mef2C.35,36 Indeed, in skeletal muscle, Mef2C is not only downstream of the bHLH factor MyoD but also cooperates with MyoD to enhance its transcriptional activity.37,38 The regulation of Mef2C in B cells has not been rigorously investigated, although it has been proposed that bHLH factors encoded by the E2A gene, E12 and E47, might regulate Mef2C expression in B cells.39

Interestingly, the B-cell phenotype observed in Mef2C-deficient mice is highly reminiscent of the defects in B lymphopoiesis that accumulate during aging. One hallmark of B-cell aging is a severely reduced pre–B-cell compartment without a concomitant reduction in mature IgM+ cells, occurring during the second year of life, and is most pronounced in mice older than 15 months.40 Importantly, Mef2C-deficient mice exhibited an appreciable reduction of the pre–B-cell compartment already by 9 months of age. Although the mechanisms that underlie B-cell aging remain undefined, aged B-lineage cells have decreased rates of proliferation as well as increased rates of apoptosis41 and have been associated with alterations in the levels of expression of Bcl-xL42,43 and E12 and E47.40 Intriguingly, a recent study in which Mef2C was conditionally deleted by CD19-Cre indicates that Mef2C is required for B-cell survival after IgM-induced activation via a Bcl-xL– and cyclin-dependent mechanism.44 Therefore, Mef2C deletion may exacerbate B-cell aging by negatively impacting cell survival mechanisms in B lymphoid cells.

Of note, we observed a slight expansion of the myeloid compartment in older Mef2C-deficient mice. Although myeloid compensation is commonly associated with the decline in B-lymphopoiesis during aging, a recent study showed that Mef2C can modulate cell-fate decisions between monocyte and granulocyte differentiation.45 Therefore, it remains to be defined whether the increase of myeloid cells observed in older mice is the result of a cell-intrinsic requirement for Mef2C within myeloid cells or an indirect result of B-cell aging (see proposed model in Figure 6).

Furthermore, the role of Scl in hematologic malignancies and the recent implication of Mef2C as a cooperating oncogene in leukemia46-49 raise the hypothesis that Mef2C may be regulated by Scl or other bHLH factors during leukemogenesis. However, the fact that Scl is unable to bind and activate the Mef2C promoter in erythroid cells where Scl is highly expressed suggests that additional prerequisites have to be fulfilled to activate Mef2C expression. Therefore, unraveling the mechanisms by which Mef2C expression is regulated and how Mef2C subsequently controls cell proliferation and survival in different tissues may elucidate not only these physiologic processes but also the pathogenesis of malignant blood diseases.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Suvi Aivio, Mattias Magnusson, and Yanling Wang for excellent technical assistance, the staff at University of California–Los Angeles Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine laboratory for blood analysis, Marianne Cilluffo and Alicia Thompson for their expertise in electron microscopy, the University of California–Los Angeles Flow Cytometry Core for FACS sorting, and Kenneth Dorshkind for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Cancer Research Coordinating Committee (Davis, CA), the Stop Cancer Foundation (Los Angeles, CA), the V Foundation for Cancer Research (Cary, NC) and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (San Francisco, CA; to H.K.A.M.), and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award at University of California–Los Angeles (Bethesda, MD; GM07185, to K.E.R).

Authorship

Contribution: C.G. and K.E.R. performed experiments, analyzed results, made the figures, and wrote the paper; L.M.G. and H.H. performed experiments and analyzed results; R.F. and M.P. analyzed results; S.K.K. and E.M.-R. designed experiments and analyzed results; R.B.-D. and E.O. generated conditional knockout mouse model; A.V.K. and S.A. supplied essential materials and designed experiments; S.H.O. designed experiments; and H.K.A.M. designed and performed experiments, analyzed results, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hanna K. A. Mikkola, University of California–Los Angeles, Department of Molecular, Cell and Developmental Biology, 621 Charles E. Young Dr South, LSB 2204, Los Angeles, CA 90095; e-mail: hmikkola@mcdb.ucla.edu.

References

Author notes

*C.G. and K.E.R. contributed equally to this study.