Abstract

Mean platelet volume (MPV) and platelet count (PLT) are highly heritable and tightly regulated traits. We performed a genome-wide association study for MPV and identified one SNP, rs342293, as having highly significant and reproducible association with MPV (per-G allele effect 0.016 ± 0.001 log fL; P < 1.08 × 10−24) and PLT (per-G effect −4.55 ± 0.80 109/L; P < 7.19 × 10−8) in 8586 healthy subjects. Whole-genome expression analysis in the 1-MB region showed a significant association with platelet transcript levels for PIK3CG (n = 35; P = .047). The G allele at rs342293 was also associated with decreased binding of annexin V to platelets activated with collagen-related peptide (n = 84; P = .003). The region 7q22.3 identifies the first QTL influencing platelet volume, counts, and function in healthy subjects. Notably, the association signal maps to a chromosome region implicated in myeloid malignancies, indicating this site as an important regulatory site for hematopoiesis. The identification of loci regulating MPV by this and other studies will increase our insight in the processes of megakaryopoiesis and proplatelet formation, and it may aid the identification of genes that are somatically mutated in essential thrombocytosis.

Introduction

Platelets are anucleate blood cell fragments that play a key role in maintaining primary hemostasis and in wound healing. Mean platelet volume (MPV) and platelet count (PLT) are tightly regulated and inversely correlated in the healthy population. Increased MPV represents a strong, independent predictor of postevent outcome in coronary disease and myocardial infarction,1,2 and changes of either parameter outside the normal ranges are routinely used to ascertain and manage a large number of clinical conditions.

Studies in rodents, primates, and twins have confirmed that blood cell quantitative traits, such as MPV and PLT, have high heritability levels.3-5 Genome-wide association studies that used dense genotyping in thousands of subjects have greatly improved the resolution of such complex polygenic traits in humans.6,7 We therefore reasoned that it should be possible to identify novel quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for MPV and PLT by a similar approach. The identification of such loci will provide new insights in the complex cellular processes of megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation. In addition, it may contribute to our understanding of premalignant conditions such as polycythemia vera and particularly essential thrombocytosis (ET), in which somatically acquired mutations in the JAK2 gene explain only a fraction of cases.8

Megakaryocytes (MKs), the platelet precursor cells, originate from pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in a stepwise process of fate determination and proliferation controlled by the cytokine thrombopoietin9 and several extracellular matrix proteins (ECMPs).10-12 After migration of the MK progenitors from the HSC niche to the bone marrow, platelets are formed via the tightly regulated process of proplatelet formation (PPF) from mature polyploid MKs.13 Transendothelial proplatelet ends are exposed to shear, triggering the final step of this process.14 The molecular machineries underlying megakaryopoiesis and PPF have been studied in some detail, but many aspects are ill understood.15 Most information has been obtained from studies on the genetic basis of rare inherited syndromes of abnormal megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation.16,17 Further insight has been gained from gene knockout experiments in mice and RNAi gene silencing in human HSCs and MKs, which have shown the crucial role of the gene MEIS1,18 microRNAs (miR-150 and miR-146a),19,20 and NFE221 in fate determination and PPF.

To date, common genetic variants in humans controlling MPV have not been identified. Here, we report on the first genetic locus on chromosome 7q22.3, associated with MPV and, intriguingly, also with differences in platelet function. Notably, the 65-kilobase (kb) recombination interval harboring the association signal is located in a chromosomal region frequently rearranged in myeloid malignancies.22

Methods

Population samples

The discovery sample consisted of 1221 healthy donors from the UK Blood Services Common Control (UKBS-CC1) genotyped with the Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) 500K Array.23 Four replication samples were also assessed, including 1050 subjects from the TwinsUK adult twin registry (www.TwinsUK.ac.uk), genotyped with the HumanHap300 chip (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and imputed using genotype data from the HapMap project24 ; 1601 subjects from the Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung in der Region Augsburg (KORA) cohort from the region of Augsburg in Germany, genotyped with the same Affymetrix 500K Array25 ; a second panel of 1304 subjects from the UKBS-CC collection (UKBS-CC2); and 3410 subjects from the Cambridge BioResource (CBR). Characteristics of the sample collections and genotyping are given in Document S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Samples and phenotype information were obtained from all study subjects with written and signed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics committee approval was obtained for each of the study cohorts according to the national rules and regulations that are in place in the different member states of the European Union.

Statistical analyses

Associations of blood traits with genotypes were performed with linear regression on natural log-transformed (MPV, red blood cell count [RBC], and white blood cell count [WBC]) or untransformed (MCH, MCHC, PLT, MCV, HB) variables after adjustment for age, sex, and instrument (TwinsUK). Analyses were performed with the software PLINK26 (UKBS-CC1, UKBS-CC2, CBR) or MACH2QTL (KORA27 ). Association analyses in the TwinsUK collection were performed with a score test and variance components to adjust for family structure with the use of the software MERLIN.28 Meta-analysis statistics were obtained with a weighted z statistics method, where weights were proportional to the square root of the number of subjects examined in each sample and selected such as the squared weights sum to be 1.29 Calculations were implemented in the METAL package.27 Calculations of effect sizes for quantitative traits were performed with the inverse variance method and custom scripts in the R environment (www.r-project.org).

Gene expression analysis

For this study, we focused on the 1-MB region centered on rs342293, which contains 6 annotated genes. For platelets, mRNA from 35 subjects spanning the range of platelet reactivities in the Platelet Function Cohort of 500 healthy subjects and with known rs342293 genotype were assessed with the Illumina HumanWG-6 v1 Expression BeadChip arrays (Illumina) as described previously.30 In short, leukocyte-depleted platelet concentrates were obtained by apheresis from the 35 donors, and EDTA (pH 8.0, final concentration 5 mM) was added, and residual leukocytes were removed by centrifugation at 140g for 15 minutes. An aliquot of the resulting platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was used for leukocyte counting by flow cytometry (LeukoCOUNT; Becton Dickinson, Oxford, United Kingdom), and the remaining PRP was centrifuged at 1500g for 10 minutes to pellet the platelets. The supernatant was then removed, and the platelets were lysed in TRIzol (10 mL per 4 × 1010 platelets; Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom), and RNA was isolated following the manufacturers' instructions. RNA quality, purity, and quantity were assessed by nonreducing agarose gel electrophoresis and duplex reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to determine the levels of the pan-leukocyte marker CD45 (PTPRC) as described previously.31 Before microarray analysis, total RNA was further purified with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (QIAGEN, Crawley, United Kingdom).

Erythroblast (EB) and MK transcriptome data were obtained from an earlier study.32 In short, paired samples of both types of precursors were obtained by culturing of CD34+ HSCs purified from cord blood. After approximately 8 days of culture in the presence of specific growth factors, EBs and MKs underwent fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) with monoclonal antibodies against glycophorin A (anti-CD235a) and the integrin αIIb (anti-CD41), respectively. Purified RNA was amplified and labeled with the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Applera, Austin, TX). Biotinylated cRNA was applied to Illumina HumanWG-6 v1 Expression BeadChips and hybridized overnight at 58°C. Chips were washed, detected, and scanned according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The corresponding probes for the 6 genes in the 1-MB interval centered on rs342293 are PBEF1 (GI_5031976-I), FLJ36031 (GI_31343528-S), PIK3CG (GI_21237724-S), PRKAR2B (GI_4506064-S), HBP1 (GI_21361410-S), and COG5 (GI_32481217-A). Array processing was performed under the R/BioConductor environment (www.bioconductor.org) with the “lumi” package.33 Probe intensities were first transformed to stabilize the variance across the intensity range with the VST transform from lumi.33 This transformation makes use of the multiple measurements per probe particular to the Illumina platform. It approaches a log2 transformation at high intensities but performs better at lower signal intensities. Subsequently, the transformed signals were median-normalized. The probe detection level was assessed with the use of Illumina's detection P value, where at least 18 of the 35 samples were required to have a detection of P less than .01. This level roughly corresponds to a normalized signal intensity of 7.7. Tests of association with rs342293 genotype were performed with linear regression and permutation testing (n = 10 000) with the software PLINK.26

Bioinformatics prediction of altered transcription factor binding sites

The search for potentially altered transcription factor binding sites was performed as follows. The 4-bp regions surrounding each allele of rs342293 (20-bp extension in each direction) were searched for transcription factor binding sites present in TRANSFAC 7.0 public (http://www.gene-regulation.com/) with MotifScanner34 with a prior of 0.1 and a background model EPD-3 (third-order Markov chain based on eukaryotic promoter sequences). Motifs that were called for only one of the alleles were selected. This list was further reduced to 2 elements (EVI1 and GATA) by only considering motifs for which the putative transcription factors were detected above background levels in the genome-wide expression profiles of MKs obtained as detailed in the previous paragraph.

Measurement of platelet response

Platelet reactivity was analyzed by whole-blood flow cytometry in a panel of 500 healthy control donors from the Platelet Function Cohort (PFC) as described previously.35 Briefly, healthy regular blood donor subjects were recruited from the NHS Blood and Transplant clinic in Cambridge. Blood was processed within 10 minutes of venesection, and 5 μL citrated whole blood was added to 50 μL HBS containing aspirin (100 μM), hirudin (10 U mL−1), and, for cross-linked collagen-related-peptide (CRP-XL)–stimulated samples, apyrase (4 U mL−1). Samples were coincubated for 20 minutes at room temperature with either ADP (10−8, 10−7, 10−6 M) or CRP-XL (0.01, 0.1, 1 μg mL−1), and with FITC-antifibrinogen, PE–anti-CD62P, or FITC-labeled annexin V. The reaction was stopped by hundred-fold dilution in formyl saline (0.2% formaldehyde in 0.9% NaCl). Negative controls for the P-selectin antibodies were set with an appropriate isotype control and for the antifibrinogen antibody with samples incubated with the antibody in the presence of 6 mM EDTA. Platelets were then washed, incubated with FITC-labeled secondary antibody for 30 minutes, washed again, and resuspended in PBS containing 0.32% trisodium citrate and 0.25% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a Beckman Coulter EPICS Profile XL (Beckman Coulter, High Wycombe, United Kingdom). The percentage of positive cells (annexin V and fibrinogen binding) and median fluorescence intensity (MFI; P-selectin expression) were recorded. Measurements were then adjusted for confounders by logit transformation and by fitting a multiple linear regression model to the response, with sample processing time as a continuous predictor and type of donor as a categorical predictor.

Results

Genome-wide associations with MPV

We performed a genome-wide association analysis for MPV at 361 352 SNPs profiled with the Affymetrix Gene Chip 500K mapping array set36 in 1221 healthy donors from the UKBS-CC1 collection with available phenotype.23 After applying stringent QC criteria, only one genomic region displayed association with P less than 10−5 at multiple SNPs (rs342214, rs342242, rs342275, rs342293; P = 1.32 × 10−6-2.21 × 10−7). Because the 4 SNPs were highly correlated (r2 = 0.94 in the HapMap CEU sample), we selected the SNP with the strongest evidence for association, rs342293, for replication in additional population samples. These included 2 of our population-based cohorts with available genome-wide typing results for MPV, namely (1) 1050 subjects from the TwinsUK adult twin registry, genotyped with the HumanHap300 chip (Illumina) and imputed with genotype data from the HapMap project24 ; (2) 1601 subjects from the KORA cohort from the region of Augsburg in Germany, genotyped with the same Affymetrix 500K array.25 In addition, we genotyped rs342293 in 2 further collections: a second panel of 1304 subjects from the UKBS-CC2 and 3410 subjects from the CBR. The characteristics of the collections are described in the Document S1. The association of rs342293 with MPV was strongly replicated in all the collections tested, with a P value of 1.08 × 10−24 in the combined sample of 8586 subjects (Table 1). All collections displayed associations of similar magnitude, with a total increase of 0.016 log fL (95% CI, 0.013-0.018) per copy of the minor G allele. On average, genetic variation at this locus explains 1.5% (range, 0.78%-2.45%) of total variance in MPV in a model adjusted for sex and age.

Association of rs342293 with mean platelet volume in the 5 studies and meta-analysis summary statistics for the blood traits investigated

| . | Subjects, n . | G allele frequency . | Mean ± SD level of MPV, fL . | Per-G allele effect (SE), log (fL)* . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG . | GC . | CC . | |||||

| Cohort | |||||||

| UKBS-CC1 | 1221 | 0.46 | 9.62 ± 1.02 | 9.50 ± 1.03 | 9.21 ± 0.88 | 0.022 (0.004) | 2.21 × 10−7 |

| TwinsUK | 1050 | 0.46 | 11.29 ± 1.10 | 11.06 ± 1.06 | 10.94 ± 0.93 | 0.014 (0.004) | 3.08 × 10−4 |

| KORA F3 500K | 1601 | 0.45 | 8.81 ± 1.02 | 8.71 ± 0.91 | 8.56 ± 0.90 | 0.014 (0.004) | 1.6 × 10−4 |

| CBR | 3410 | 0.45 | 9.63 ± 0.93 | 9.02 ± 0.91 | 8.93 ± 0.91 | 0.013 (0.002) | 2.03 × 10−7 |

| UKBS-CC2 | 1304 | 0.46 | 9.76 ± 1.09 | 9.39 ± 1.01 | 9.30 ± 1.02 | 0.023 (0.004) | 3.29 × 10−8 |

| Total | 8586 | — | — | — | — | 0.016 (0.001) | 1.08 × 10−24 |

| Meta-analysis of other blood cell indices | |||||||

| Platelet count, ×109/L | — | — | — | — | — | −4.553 (0.802) | 7.19 × 10−8 |

| Hemoglobin concentration, g/dL | — | — | — | — | — | −0.020 (0.013) | .119 |

| RBC count, log 1012/L | — | — | — | — | — | −0.002 (0.001) | .070 |

| WBC count, log 109/L | — | — | — | — | — | −0.001 (0.004) | .730 |

| MCH, pg | — | — | — | — | — | 0.018 (0.025) | .509 |

| MCHC, g/dL | — | — | — | — | — | −0.006 (0.011) | .516 |

| MCV, fL | — | — | — | — | — | 0.087 (0.064) | .163 |

| . | Subjects, n . | G allele frequency . | Mean ± SD level of MPV, fL . | Per-G allele effect (SE), log (fL)* . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG . | GC . | CC . | |||||

| Cohort | |||||||

| UKBS-CC1 | 1221 | 0.46 | 9.62 ± 1.02 | 9.50 ± 1.03 | 9.21 ± 0.88 | 0.022 (0.004) | 2.21 × 10−7 |

| TwinsUK | 1050 | 0.46 | 11.29 ± 1.10 | 11.06 ± 1.06 | 10.94 ± 0.93 | 0.014 (0.004) | 3.08 × 10−4 |

| KORA F3 500K | 1601 | 0.45 | 8.81 ± 1.02 | 8.71 ± 0.91 | 8.56 ± 0.90 | 0.014 (0.004) | 1.6 × 10−4 |

| CBR | 3410 | 0.45 | 9.63 ± 0.93 | 9.02 ± 0.91 | 8.93 ± 0.91 | 0.013 (0.002) | 2.03 × 10−7 |

| UKBS-CC2 | 1304 | 0.46 | 9.76 ± 1.09 | 9.39 ± 1.01 | 9.30 ± 1.02 | 0.023 (0.004) | 3.29 × 10−8 |

| Total | 8586 | — | — | — | — | 0.016 (0.001) | 1.08 × 10−24 |

| Meta-analysis of other blood cell indices | |||||||

| Platelet count, ×109/L | — | — | — | — | — | −4.553 (0.802) | 7.19 × 10−8 |

| Hemoglobin concentration, g/dL | — | — | — | — | — | −0.020 (0.013) | .119 |

| RBC count, log 1012/L | — | — | — | — | — | −0.002 (0.001) | .070 |

| WBC count, log 109/L | — | — | — | — | — | −0.001 (0.004) | .730 |

| MCH, pg | — | — | — | — | — | 0.018 (0.025) | .509 |

| MCHC, g/dL | — | — | — | — | — | −0.006 (0.011) | .516 |

| MCV, fL | — | — | — | — | — | 0.087 (0.064) | .163 |

MPV indicates mean platelet volume; SD, standard deviation; UKBS-CC, UK Blood Services Common Controls; KORA, Kooperative Gesundheitsforschung in der Region Augsburg; CBR, Cambridge BioResource; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; and MCV, mean RBC volume.

After adjustment for age and sex, the proportion of total variation in MPV explained by rs342293 is UKBS-CC1, 2.25%; UKBS-CC2, 2.33%; TwinsUK, 1.27%; CBR, 0.79%; and KORA F3, 0.89%.

PLT and MPV are known to be negatively correlated, and this was replicated in all the sample collections investigated (average correlation coefficient r = −0.39). When tested, we found that the minor (G) allele at rs342293 was also significantly associated with reduced PLT (P = 7.19 × 10−8; per G-allele effect, −4.55 109/L; 95% CI: −6.12 to −2.98; Table S2A). The corresponding platelet count levels (mean ± SD) for the 3 genotypes in the CBR sample were GG = 242.8 ± 55.2 109/L, GC = 247 ± 54.0 109/L, CC = 249.3 ± 56.4 109/L. Association of rs342293 with PLT conditioning on MPV, however, was not significant (P = .472; Table S3), indicating that the effect of rs342293 on count is fully explained by its association with volume.

Because MKs and EBs share a common bipotent precursor cell, we investigated whether rs342293 has a similar effect on red cell volume and number. Genotypes at rs342293 were not associated with any of the red blood cell traits tested (Table S2), indicating that the effect of this SNP is unique to regulatory processes in the megakaryocytic lineage.

SNP rs342293 modifies gene expression

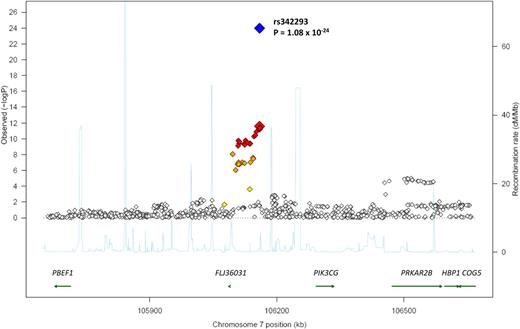

We fine-mapped the region by meta-analysis of 918 genotyped and imputed SNPs from 3 genome-wide scans over a 1-MB interval centered on rs342293 (Figure 1). The strongest association signal was detected at rs342293. The hypothetical gene FLJ36031 was most proximal to the SNP at a distance of 70 889 bp, and 5 additional genes were identified within the 1-MB interval studied (Figure 1). We assayed expression of the 6 genes in stem cell–derived MKs and EBs with whole-genome Illumina HumanWG-6 (v1) Expression BeadChip arrays.30,32 All 6 genes were transcribed in MKs (Figure 2A). Remarkably, PIK3CG was robustly transcribed in MKs but not in EBs.

Results of genome-wide association scan. Regional plot of mean platelet volume association results for the chromosome 7 loci across the 3 GWAS. Meta-analysis log10P values are plotted as a function of genomic position (Build 36). The P value for the lead SNP rs342293 is denoted by large red (GWAS) and blue (combined discovery and replication) diamonds. Proxies are indicated with diamonds of smaller size, with colors assigned based on the pairwise r2 values with the lead SNP in the HapMap CEU sample: red (r2 > 0.8), orange (0.5 < r2 < 0.8), or yellow (0.2 < r2 < 0.5). White indicates either no LD with the lead SNP (r2 < 0.2), or loci in which such information was not available. Recombination rate estimates (HapMap Phase II) are given in light blue, Refseq genes (NCBI) in green.

Results of genome-wide association scan. Regional plot of mean platelet volume association results for the chromosome 7 loci across the 3 GWAS. Meta-analysis log10P values are plotted as a function of genomic position (Build 36). The P value for the lead SNP rs342293 is denoted by large red (GWAS) and blue (combined discovery and replication) diamonds. Proxies are indicated with diamonds of smaller size, with colors assigned based on the pairwise r2 values with the lead SNP in the HapMap CEU sample: red (r2 > 0.8), orange (0.5 < r2 < 0.8), or yellow (0.2 < r2 < 0.5). White indicates either no LD with the lead SNP (r2 < 0.2), or loci in which such information was not available. Recombination rate estimates (HapMap Phase II) are given in light blue, Refseq genes (NCBI) in green.

Association of rs342293 with platelet expression and function. (A) Heatmap of mRNA expression for 6 genes within a 1-MB interval. VST-transformed signal intensities were median-normalized, and values were averaged across biologic replicates in erythroblasts (EB; n = 4), megakaryocytes (MK; n = 4), and platelets (n = 35, whereby expression values were averaged based on rs342293 genotype). Signal intensities obtained with platelets were normalized independently from the MK and EB samples. (B) Boxplots of associations between rs342293 genotype and mRNA levels in 35 platelet samples, shown for the 2 genes with expression above detection level (PIK3CG and PRKAR2B). (C) Association of rs342293 genotypes with measurements of platelet reactivity in the Platelet Function Cohort. (Top) Standardized residuals of logit transformed levels of P-selectin expression (left), and fraction of platelets binding fibrinogen (middle) or annexin V (right) in response to the collagen mimetic CRP-XL. (Bottom) P-selectin expression and fibrinogen binding in response to ADP. Horizontal bars indicate averages and error bars indicate 1 standard deviation.

Association of rs342293 with platelet expression and function. (A) Heatmap of mRNA expression for 6 genes within a 1-MB interval. VST-transformed signal intensities were median-normalized, and values were averaged across biologic replicates in erythroblasts (EB; n = 4), megakaryocytes (MK; n = 4), and platelets (n = 35, whereby expression values were averaged based on rs342293 genotype). Signal intensities obtained with platelets were normalized independently from the MK and EB samples. (B) Boxplots of associations between rs342293 genotype and mRNA levels in 35 platelet samples, shown for the 2 genes with expression above detection level (PIK3CG and PRKAR2B). (C) Association of rs342293 genotypes with measurements of platelet reactivity in the Platelet Function Cohort. (Top) Standardized residuals of logit transformed levels of P-selectin expression (left), and fraction of platelets binding fibrinogen (middle) or annexin V (right) in response to the collagen mimetic CRP-XL. (Bottom) P-selectin expression and fibrinogen binding in response to ADP. Horizontal bars indicate averages and error bars indicate 1 standard deviation.

We tested the effect of rs342293 on gene transcription in platelets from 35 subjects obtained with the same Illumina HumanWG-6 (v1) arrays as detailed in “Methods.”30 Because of RNA decay in platelets, signal intensities for platelet RNAs were on average 2-fold lower than signal intensities in MKs (Figure 2A). In addition, approximately 50% of the transcripts present in MKs could not be detected in platelets. We observed that the transcripts of 2 of the 6 genes, PIK3CG and PRKAR2B, were robustly detected in platelet RNA samples, and that subjects carrying the GG genotype had significantly higher PIK3CG mRNA levels (8.73 ± 0.11) compared with GC (8.44 ± 0.10) and CC (8.33 ± 0.12) genotypes (permutation P = .047; Figure 2B). We did not observe a significant association with PRKAR2B expression (permutation P = .12), although we note that GG homozygotes on average had higher expression (11.99 ± 0.15) compared with CG (11.5 ± 0.14) and CC (11.45 ± 0.28) subjects.

It is possible that the observed effect of rs342293 on PIK3CG transcript levels is the result of trans-acting elements. We therefore predicted the effect of each allele of rs342293 for potentially altered transcription factor binding sites. A region of 41 bases centered on rs342293 was used for a search in the TRANSFAC 7.0 database37 with MotifScanner as described in “Methods.” Motifs that were called for only one of the alleles were selected, leaving 12 potential transcription factor binding sites that were altered by the SNP. We further investigated the expression of all the 12 transcription factors in MKs32 and found that only 2 were robustly expressed in MKs, GATA-1/2 and EVI1. In both cases the C > G change leads to the loss of the putative binding site.

SNP rs342293 modifies the level of annexin V binding to CRP-XL–activated platelets

The regulation of MPV is integrally linked to megakaryopoiesis and PPF, which depends on signals received by MKs from cytokines and ECMPs. The interaction with fibrinogen and collagen is considered central to this process, with the former driving platelet formation through the αIIbβ3 integrin11,12 and the latter having an inhibitory effect mediated via the α2β1 integrin. Further outside-in signals may be emanating from the interaction of collagen with its activatory and inhibitory signaling receptors glycoprotein (GP) VI and LAIR1, respectively.10,38 To determine whether rs342293 genotypes exert an effect on the signaling pathway downstream of the GPVI/Fcγ chain complex, we interrogated the platelet function phenotypes in our PFC of 500 healthy subjects. Two measures of platelet function were tested, namely fibrinogen binding (a measure of αIIbβ3 activation) and P-selectin expression (a measure of α granule release), after activation of platelets with either the GPVI-specific collagen mimetic CRP-XL or ADP.35 We observed that subjects carrying the G allele showed a trend of decreased fibrinogen binding and P-selectin expression after activation of platelets with CRP-XL (P = .05 and .08, respectively; Figure 2C). No effect of genotype was observed when platelets were activated with ADP (P = .32 and .15). We next tested association with annexin V binding to CRP-XL–activated platelets from 84 subjects from the same cohort. Expression of negatively charged phospholipids reported by annexin V binding is a reliable measure of membrane asymmetry and platelet prothrombotic potential.39 We found that homozygotes for the G allele at rs342293, which is associated with higher MPV levels, on average had fewer platelets binding annexin V compared with GC and CC genotypes (P = .003; Figure 2C). This indicates that the level of expression of phosphatidylserine after activation by CRP-XL is modified by this SNP, an observation consistent with the observed trend of reduced fibrinogen binding.

Discussion

We performed a genome-wide association analysis for MPV in 1221 healthy subjects followed by replication in 7365 subjects from 4 sample collections and identified the first common (minor allele frequency [MAF], 0.45-0.46 in Northern Europeans) QTL robustly associated with MPV levels in the general population. The genetic association signal was localized in a relatively small (65 kb) intergenic region that did not contain genes, indicating that regulation of platelet volume and function are probably mediated through cis- or trans-regulatory effects. The observation that rs342293 modifies the response of platelets to CRP-XL and the volume of platelets, but not the volume of red cells, indicates that the effect of the SNP is restricted to the MK lineage.

Our data, however, do not provide conclusive evidence on which genes may underlie variation in MPV and function. All 6 genes within the arbitrarily chosen 1-MB interval centered on rs342293 are transcribed in MKs, a surprising finding given that only approximately 40% of all human genes are transcribed in MKs.32 The transcript level of PIK3CG and PRKAR2B in platelets was robust enough to answer the question whether the implicated SNP exerts an effect on the respective transcript levels. This showed a nominally significant effect for PIK3CG but not for PRKAR2B (Figure 2B). Interestingly, to note that subjects homozygous for the G allele had higher PRKAR2B transcript levels than CG and CC subjects.

Both these genes are biologically plausible candidates for genes affecting platelet volume and function. PICK3CG encodes for the γ chain of pi3/pi4-kinase, which is responsible for the synthesis of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PtdIns[3,4,5]P3, PIP3) by conversion of PtdIns-3,4-biphosphate.40 The formation of PIP3 by PIK3CG in MKs and platelets is a key step in the signal transduction cascades leading to the release of calcium from the intracellular stores and controlling cellular movement, adhesion, and contraction, all 3 essential to megakaryopoiesis and PPF. It is also an essential intermediary in the regulation of phospholipase C (PLCγ2) in MKs and platelets in response to collagen.41 PI3Kγ-deficient mice display impaired aggregation after stimulation with ADP, but not after stimulation with collagen or thrombin, and are protected from death caused by ADP-induced platelet-dependent thromboembolic vascular occlusion.42 The observation that the PIK3CG transcript is absent from EBs (Figure 2A) is compatible with the lineage-restricted effect of rs342293 on cell volume. PRKAR2B encodes the β chain of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, which has an opposing effect to PIK3CG and reduces the release of intracellular calcium by the phosphorylation of ITPR3, the receptor for PIP3.43,44

In our study, the minor G allele at rs342293 was associated with increased MPV (P = 1.08 × 10−24) and also with decreased platelet reactivity measured as the proportion of activated platelets binding annexin V (P = .003) and the level of fibrinogen binding (P = .05). The directionality of association between MPV and the number of annexin V–reactive platelets, measured indirectly through the association with rs342293, thus would appear to support a negative correlation between these 2 variables. This contradicts the positive correlation between platelet volume and thrombogenicity which has been suggested by several groups but remains disputed.2

The differential functional response of platelets of different genotype on activation with CRP-XL indicates that sequence variation in the 7q22.3 region probably most likely exerts its effect on molecular events downstream of the GPVI/Fc receptor γ chain complex. We consider it unlikely that the observed association between sequence variation at rs342293 and the platelet response to CRP-XL is at the level of GPVI membrane expression, because the binding of the anti-GPVI monoclonal antibody HY101 did not differ significantly between the 3 genotype groups from the PFC (data not shown, but see Jones et al35 ). There are several plausible explanations why no effect of rs342293 was observed on platelet activation by ADP.

First, ADP is a weaker agonist, and the range of values for fibrinogen binding in the PFC was less widely distributed than compared with the range observed after activation with CRP-XL.35 Second, ADP is less effective in bringing about the expression of phosphatidylserine and annexin V binding.45 Third, the effect of SNP rs342293 on function may be pathway specific. This is a reasonable assumption that has been validated in our recently completed study of 96 candidate genes encoding proteins in the ADP and CRP-XL pathways, in which we observed that sequence variation in 16 genes was significantly associated with the levels of platelet activation by ADP or CRP-XL (P ≤ .005). For 5 of these genes the effect was restricted to the CRP-XL activation pathway.46

It remains to be established whether the effect of rs342293 CRP-XL induced annexin V binding to platelets is relevant for the regulation of platelet volume during PPF. Previous studies have provided several lines of evidence that apoptosis and platelet formation are integrally linked.47 The molecular events that lead to the expression of phosphatidylserine in CRP-XL–activated platelets are very similar to those observed in the process of apoptosis. We therefore reason that SNP rs342293 may modify the PPF process with the same directionality as observed for platelet function.

Alternatively, it is possible that the 65-kb region identified in this study harbors trans-acting regulatory elements relevant to hematopoiesis and especially megakaryopoiesis. We did obtain computational evidence that the C allele may introduce a binding site for GATA-1/2 and EVI1, a finding that will require experimental validation. Both GATA-1 and EVI1 are key transcription factors for megakaryopoiesis. EVI1 is located on chromosome band 3q26, and rearrangements in this region can lead to its overexpression in hematopoietic cells leading to acute myeloid leukemias, which are frequently associated with dystrophic megakaryopoiesis.48 GATA-1 knockdown mice have severe thrombocytopenia,49 and rare nonsynonymous SNPs in the GATA-1 gene result in X-linked macrothrombocytopenia, confirming the pivotal role of GATA-1 in megakaryopoiesis and platelet formation.50

In conclusion, we have identified the first QTL associated with variation in platelet volume, count, and function in the normal population. The discovery that common sequence variation with a MAF of 0.45 in this region modifies platelet phenotypes warrants further experiments to unravel the genetic mechanisms underlying the observed effects. The observation that chromosomal aberrations in the same region of chromosome 7 have been linked to myeloid malignancies22 lends further support to the hypothesis that this region harbors important regulatory sites of hematopoiesis.

The 7q22.3 locus explains a small fraction (1.5%) of total variance in MPV attributable to genetic factors,5 indicating that many additional QTLs are likely to be soon discovered through further genome-wide studies involving a larger number of subjects. This may become clinically relevant because the manipulation of platelet function and number by drugs is one of the successful pharmacologic interventions in cardiovascular diseases and ET. The identification of additional QTLs for blood cell indices will improve the understanding of the complexity of fate determination in hematopoiesis and the molecular machinery underlying platelet formation and function. This may in the future translate into a new generation of safer drugs.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff members of CBR for donor recruitment and related phenotyping. Detailed acknowledgments are reported in Document S2.

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust (P.D., T.D.S., W.H.O., and N.S.), the European Union FP-5 (QLG2-CT-2002-01254; P.D., H.S., J.E., N.S., and W.H.O.), and the FP-6–funded Bloodomics Integrated Project (LSHM-CT-2004-503485; W.H.O.). Support for the UKBS-CC (W.H.O.) and TwinsUK (T.D.S.) were from The Wellcome Trust. The CBR is a resource of the Cambridge Biomedical Research Center and is funded by grants from the National Institute for Health Research, The Wellcome Trust, and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International. The MONICA/KORA Augsburg studies were funded by the Helmholtz Zentrum München, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and the German National Genome Research Network (NGFN; A.D. and T.I.).

Wellcome Trust

Authorship

Contribution: T.I., T.D.S., W.H.O., J.R.B., H.S., N.J.S., and J.E. contributed DNA samples; P.D., A. Rankin, J.S., T.I., P.B., H.P., N.A.W., S.C.P., and J.J. performed research (genotyping and gene expression); S.F.G., A.D., C.M., S.M., S.L.T., A.H.G., C.I.J., and W.E. performed phenotyping; N.S., A. Rendon, C.G., S.L.B., M.F., and B.K. analyzed the data; and N.S., T.D.S., W.H.O., S.M., C.G., A. Rendon, P.D., and A.H.G. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Willem H. Ouwehand, Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, Long Rd, Cambridge CB2 2PT, United Kingdom; e-mail: who1000@cam.ac.uk; or Nicole Soranzo, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, United Kingdom; e-mail: ns6@sanger.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

*N.S., A. Rendon, and C.G. contributed equally to this study.

†T.D.S., P.D., and W.H.O. contributed equally to this study.