The mechanism underscoring efficacy of APC in the treatment of sepsis is still unresolved.1 The dual nature of APC as a potent antithrombotic and cytoprotective agent complicates the task, but in this issue of Blood, Mosnier and colleagues offer a compelling solution and challenge the molecular underpinnings of APC function.

Ala scanning mutagenesis of the activation peptide singles out E149A, a mutant activated protein C (APC) that exhibits enhanced anticoagulant activity but greatly diminished cytoprotective effects compared with wild-type. Notwithstanding its enhanced antithrombotic activity in vivo, the variant APC is poorly effective in reducing endotoxin-induced murine mortality. Together with recent findings on a different APC variant with greatly reduced anticoagulant activity but normal cytoprotective function,2 this important observation by Mosnier et al demonstrates that the antithrombotic activity of APC is neither necessary nor sufficient to ameliorate the outcome of sepsis.3 It is the cytoprotective function of APC that is likely responsible for clinical efficacy, and the antithrombotic activity would only promote unwanted bleeding.

The groundbreaking discovery of the signaling properties of APC mediated by endothelial protein C receptor (EPCR)–assisted cleavage of PAR14 has revealed that APC is endowed with 2 distinct and physiologically important functions. APC acts as an anticoagulant by inactivating clotting factor Va with the assistance of the cofactor protein S. On the other hand, APC acts as a cytoprotective agent when it cleaves PAR1 on the surface of endothelial cells with the assistance of EPCR. Spatial separation of the underlying epitopes affords dissociation of the 2 functions by protein engineering, as previously documented in thrombin.5 The goal is more than academic. APC variants with exclusive anticoagulant or cytoprotective activity not only provide essential reagents to dissect the functions of the enzyme in vivo, but also offer ways to improve on existing pharmacological intervention. Bleeding complications encountered in the clinical use of APC (Xigris) for the treatment of sepsis1 could be eliminated by a variant APC that has selectively lost its anticoagulant activity.

Protein engineering of APC has already achieved important milestones. Mosnier et al have previously constructed a variant APC with greatly reduced anticoagulant activity but normal cytoprotective function.6 The variant is as effective as wild type in reducing mortality after LPS challenge and enhances the survival of mice subjected to polymicrobial peritoneal sepsis.3 Yang et al have recently identified a variant APC with greatly compromised cytoprotective function but normal anticoagulant activity.7 The E149A mutant now reported by Mosnier et al further improves on the anticoagulant activity of APC in the presence of protein S at the expense of its cytoprotective function. The findings are more than a refinement of existing knowledge due to the peculiar location of E149 in the activation peptide of APC.

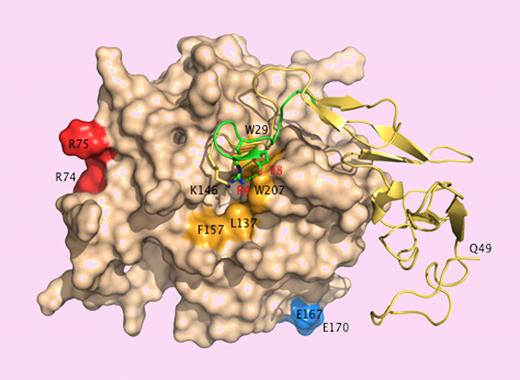

A patch of positively charged residues on the 30- and 70- loops (K37, K38, K39, R74 and R75) in the catalytic domain of APC provides an exosite for factor Va binding.6 Residues E167 and E170 on the short 170-helix are important for PAR1 recognition.7 These epitopes face the front of the enzyme and are easy targets of substrates like factor Va or PAR1 approaching the active site cleft. On the other hand, E149 is located in the back of the molecule and on the opposite side of the catalytic domain relative to the active site cleft. A fragment of the activation peptide encompassing E149 binds directly to factor Va,8 suggesting that the epitope of this substrate extends to the back of the catalytic domain of APC where docking could be promoted in the presence of protein S when E149 is mutated to Ala. That would explain the enhanced anticoagulant activity of the E149A mutant. The reduced cytoprotective activity of the mutant is more difficult to rationalize in view of its unperturbed interaction with EPCR and PAR1. The activation peptide of APC folds like the A chain of thrombin, and K146, the last residue of the activation peptide visible in the crystal structure of APC, occupies the same position as R4 in thrombin.9 The R4A mutant of thrombin has impaired activity toward chromogenic and natural substrates due to long-range perturbation of the active site.10 Sequence alignment puts E149 in the same position as E8 in thrombin,3 which is ion-paired to R4,9 but the E8A mutant is catalytically compromised,10 whereas E149A has normal activity toward chromogenic substrates and PAR1.3

Surface representation of APC15 showing the back of the catalytic domain (wheat) connected to the EGF domains and the activation peptide (yellow ribbon). The A chain of thrombin9 -comprising residues E1c through E8 (green ribbon) is superimposed for comparison. K146 (stick) occupies a position analogous to that of R4 (stick) in thrombin. Residue E149, not resolved in the crystal structure, could engage K146 in an ion-pair interaction as E8 (stick) does with R4 in thrombin. Disruption of the ion-pair with the E149A mutation could expose a hydrophobic patch (orange) for recognition of macromolecular ligands. Residues R74, R75, E167, and E170 (chymotrypsinogen numbering) face the front of the molecule and are only partially visible in this orientation. R74 and R75 are part of the factor Va epitope.6 E167 and E170 are involved in PAR1 recognition.7

Surface representation of APC15 showing the back of the catalytic domain (wheat) connected to the EGF domains and the activation peptide (yellow ribbon). The A chain of thrombin9 -comprising residues E1c through E8 (green ribbon) is superimposed for comparison. K146 (stick) occupies a position analogous to that of R4 (stick) in thrombin. Residue E149, not resolved in the crystal structure, could engage K146 in an ion-pair interaction as E8 (stick) does with R4 in thrombin. Disruption of the ion-pair with the E149A mutation could expose a hydrophobic patch (orange) for recognition of macromolecular ligands. Residues R74, R75, E167, and E170 (chymotrypsinogen numbering) face the front of the molecule and are only partially visible in this orientation. R74 and R75 are part of the factor Va epitope.6 E167 and E170 are involved in PAR1 recognition.7

How do we reconcile the properties of the E149A mutant with our current understanding of APC signaling? The kcat/Km value for the hydrolysis of PAR1 by APC under physiologic conditions is 0.0014 μM−1s−1, or more than 10000-fold lower than that of the thrombin-PAR1 interaction.11 How can such an insignificant rate be relevant in vivo? Colocalization of EPCR and PAR1 on the membrane of endothelial cells has been invoked to solve the conundrum,12 but perhaps a paradigm shift is called for. APC may engage a different receptor to mediate some or most of its cytoprotective effects,13 or APC signaling may be amplified by the release of endogenous proteases, as recently suggested for the amplification of thrombin induced PAR1 signaling in human platelets.14 E149 and its neighbor residues may be involved in the recognition of other players besides EPCR and PAR1. The new findings by Mosnier et al remind us that we still do not know our APC.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

Acknowledgment:

The author is grateful to Austin Vogt for measuring the rate of PAR1 activation by APC. This work was supported by NIH research grants HL49413, HL58141, and HL73813.

National Institutes of Health

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal