Abstract

During infection, Toll-like receptor agonists induce natural killer (NK)–cell activation by stimulating dendritic cells (DCs) to produce cytokines and transpresent IL-15 to NK cells. Yet the cellular dynamics underlying NK-cell activation by DCs in secondary lymphoid organs are largely unknown. Here, we have visualized NK-cell activation using mice in which NK cells and DCs express different fluorescent proteins. In response to polyI:C or lipopolysaccharide, NK cells maintained a vigorous migratory behavior, establishing multiple short contacts with maturing DCs. Furthermore, mature antigen-loaded DCs that made long-lived interactions with T cells formed short-lived contacts with NK cells. The different behaviors of T cells and NK cells during activation was correlated with distinct calcium responses upon interaction with DCs. That NK cells become activated while remaining motile may constitute an efficient strategy for sampling local concentrations of cytokines around DCs in secondary lymphoid tissues.

Introduction

NK cells have the ability to recognize and destroy virally infected or transformed cells, a decision based on the integration of signals from activating and inhibitory natural killer (NK)–cell receptors.1 However, NK cells are most competent to exert their functions after an initial step of activation (also referred to as NK-cell priming) that can be provided by innate cytokines2 and interactions with accessory immune cells.3 Dendritic cells (DCs) are thought to play a major role in this process through their ability to secrete various cytokines upon microbial stimuli.4 A seminal study showed that, in mice, mature DCs could trigger NK-cell functions through a process that depended on direct cell–cell interactions.5 Subsequent in vitro experiments in mice and humans have confirmed the requirement for cellular contact, implicating surface receptors6,7 and/or local delivery of cytokines, including IL-12, IL-18, IL-2, IL-15, and type I IFN.8-14 In vivo, NK cells are also activated after various microbial infections or Toll-like receptor (TLR) stimulation, and in many cases this process depends on conventional DCs as shown by inducible DC ablation experiments15-19 or with mice that selectively lack MyD88 on DCs.20 Furthermore, NK-cell activation in response to various TLR agonists was found to rely on the ability of DCs to respond to type I IFN, to express IL-15 and IL-15Rα in a coordinate fashion, and to directly interact with NK cells for IL-15 transpresentation.15,18,21

The ability of DCs to activate NK-cell functions through cell contacts is reminiscent of their role in priming CD4 and CD8 T cells, a process that most often requires establishing hour-long cell interactions.22 In vitro, NK cells and DCs can form stable conjugates,23,24 and the corresponding immunologic synapse was found to be enriched for the presence of adhesion molecules and IL-12,23 IL-15Rα,24 or IL-18.25 How NK cells interact with DCs in vivo during priming has not yet been addressed. Two-photon imaging is currently the technique of choice to decipher cell migration and interaction in intact lymphoid organs.26 Conflicting reports have been provided on the motility of adoptively transferred NK cells in lymph nodes (LNs),27,28 but the discrepancies may be due to NK-cell isolation methods.28 To date, no data have been reported about the behavior of NK cells in situ. To gain insights into the strategy used by NK cells to collect signals during their activation in vivo, we have visualized how endogenous NK cells and DCs interact at steady state and in response to poly I:C, a synthetic analog of viral double-stranded RNA. Using mice in which endogenous NK cells and DCs are labeled with different fluorescent proteins, we found that, unlike T cells, NK cells do not form long-lived interactions with DCs during activation. Likewise, NK cells did not establish stable conjugates with activated transferred DCs. Rather, NK cells remain highly motile, allowing them to repeatedly establish multiple transient contacts with LN DCs. Such mode of action may optimize the NK cells' ability to integrate the concentration of innate cytokines produced in the close vicinity of DCs in secondary lymphoid tissues.

Methods

Mice and injections

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. Rag2−/− Marilyn TCR (T-cell receptor) mice were purchased from CDTA. Ncr1GFP/+,29 CD11c-YFP,30 Actin-CFP, and Rag−/− OT-I TCR transgenic mice were bred in our animal facility. All animal experiments were performed according to Institut Pasteur approval and institutional guidelines. When indicated, mice were injected intravenously with 100 μg poly I:C or 50 μg LPS (Invivogen) resuspended in 200 μL PBS.

Cell preparation and transfer

DCs were isolated from the spleens of mice injected with PBS or poly I:C 4 hours earlier using anti-CD11c–coated beads and an Automacs system (Miltenyi Biotec) as described.31 Purified DCs were pulsed for 10 minutes at 37°C with 10 or 100 nM SIINFEKL peptide or 1 μM Dby (NAGFNSNRANSSRSS) peptide (Neomps) or left unpulsed. In some experiments, DCs (3 × 106 cells) were injected in the footpad of recipient mice in the presence or absence of 12.5 μg poly I:C. CD8 T cells and CD4 T cells were collected from LNs of Rag−/− OT-I TCR Tg mice and Rag2−/− Marilyn TCR mice, respectively, labeled with 5 μM SNARF (Invitrogen) for 10 minutes at 37°C. Recipient mice were adoptively transferred with 6 × 106 T cells. For in vitro experiments, NK cells were purified from LNs and spleen of B6 or Rag2−/− mice using a negatively selecting purification kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and an Automacs system.

Flow cytometry

LNs were harvested and incubated 15 minutes in RPMI 1640 with 1 mg/mL collagenase and 0.05 mg/mL DNAse. Fc receptor blocking was performed using unconjugated anti-CD16/32 (BD Biosciences) for 15 minutes. Cells were stained with a combination of the following mAbs: Alexa Fluor 488–labeled anti-CD3, APC-labeled anti–Granzyme B (Invitrogen), APC-labeled anti-NK1.1 (eBiosciences), PE-labeled anti–NK1-1, Pacific Blue–labeled anti-CD3, PE-labeled anti–IFN-γ, PE-labeled anti-CD69 (BD Biosciences). Intracellular stainings were performed using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit. For detection of cell conjugates and intracellular calcium, T cells or NK cells were first labeled with the SNARF dye at 2 μM, washed, and then labeled with the calcium-sensitive dye Fluo3 AM (Invitrogen) at 5 μM in RPMI containing 0.2% pluronic for 30 minutes at room temperature. T cells or NK cells were then incubated with OVA peptide–loaded DCs purified from poly I:C–treated CFP-expressing mice at 37°C for 30 minutes. Fluo3 fluorescence was analyzed among unconjugated or conjugated T cells (or NK cells).

LN organ cultures

Mice were injected intravenously with PBS or 100 μg poly I:C and killed 5 minutes later. LNs were harvested immediately and placed at the air-liquid interface, in the upper chamber of a transwell positioned in a 24-well plate containing 200 μL culture media/well. When indicated, LNs were dissociated with surgical tweezers, and cells were cultured in 24-well plates containing 1 mL medium/well.

Confocal and 2-photon imaging

LNs were harvested and fixed in periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde; dehydrated successively in 10%, 20%, and 30% sucrose; and frozen in OCT compound. Sections (8 μm) were stained with APC-labeled anti-B220 mAb (Southern Biotechnology Associates) as described.32 Sections were mounted with the Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed with a confocal microscope. Two-photon imaging was performed with an upright microscope DM 6000B with a SP5 confocal head (Leica Microsystems). Explanted LNs were maintained at 37°C and perfused with media bubbled with a 95% O2/5% CO2 gas mixture. For intravital imaging, a popliteal LN was microsurgically exposed. The mouse was then placed on a custom-designed heated stage, and plaster bandages were used to immobilize the posterior leg. A coverslip was placed on top of the popliteal LN and glued onto the plaster cast. The LN temperature was constantly monitored and maintained at 37°C by a heated metal ring placed onto the coverslip and filled with water to immerge a 20×/0.95 NA dipping objective. Samples were excited with a Chameleon Ultra Ti:Sapphire laser (Coherent) tuned at 900 or 950 nm. Emitted fluorescence was split with a 510-nm dichroic mirror and detected by 2 non–descanned detectors. In most experiments, 8 planes spaced 5 μm apart were imaged every 30 seconds. Videos were further processed to fully separate GFP, YFP, and SNARF signals. To this end, stack of images corresponding to the fluorescence collected in channel 1 (500-510 nm) and channel 2 (510-650 nm) were created with the Image J software. Using the Calculator plus plugin, the following image stacks were produced: GFP stack = Ch1-Ch2; YFP stack = Ch1-GFP; SNARF stack = Ch2-YFP. GFP, YFP, and SNARF image stacks were then merged as a composite RGB image stack using Image J. As a result, GFP, YFP, and SNARF signals are shown in green, red, and blue, respectively. Three-dimensional cell tracking was performed with Imaris 5.7 software (Bitplane) to determine trajectories, mean cell velocities and straightness indexes. The straightness index corresponds to the ratio of the distance from origin to the total distance traveled. Cell interactions were quantified manually by assessing cell–cell juxtaposition while examining individual z-planes.

Results

Visualizing the steady state behavior of endogenous NK cells and DCs in LNs

Two recent studies have analyzed NK-cell motility in LNs after adoptive transfer of either positively or negatively bead-purified NK cells.27,28 Because the purification procedures can alter NK-cell behavior and the adoptive transfer can modify the pattern of NK-cell homing, it was important to characterize the behavior of endogenous, unmanipulated NK cells. To do so, we took advantage of Ncr1GFP/+ knock-in mice, in which GFP is specifically expressed by all NK cells.29 These animals were crossed to CD11c-YFP mice30 to simultaneously identify NK cells and the network of LN DCs.

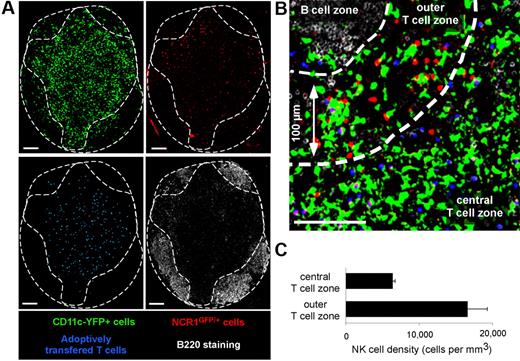

First, we assessed the distribution of NK cells in popliteal LNs of Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice by confocal microscopy (Figure 1). T- and B-cell zones were identified after transfer of dye-labeled T cells and B220 staining of frozen LN sections, respectively. In good agreement with previous studies,27,33 NK cells were particularly enriched in the most peripheral regions of the T-cell zone. NK cell density in these areas (defined as being ≤ 100 μm in distance from B-cell follicles) was 16 600 (± 2600) cells/mm3 versus 6300 (± 300) cells/mm3 in the deep T-cell zone. In addition, GFP-expressing NK cells could be readily distinguished from YFP-expressing DCs after spectral unmixing of GFP and YFP signals (Figure 1).

Visualizing endogenous NK cells and DCs using Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were adoptively transferred with SNARF-labeled CD8 T cells. A day later, popliteal LNs were harvested, and frozen sections were stained with an anti-B220 Ab and imaged by confocal microscopy. Images were then subjected to spectral unmixing. (A) Individual pseudocolored images showing DCs (YFP-positive cells, pseudocolored in green), NK cells (GFP positive, pseudocolored in red), adoptively transferred T cells (blue), and B cells (B220+ cells, white). (B) Representative confocal image showing that LN NK cells (red) are enriched at the T cell–B cell zone interface. (C) The density of NK cells was compared in the most peripheral layer of the T-cell zone (≤ 100 μm below B cell follicles) or in the rest of the T-cell area (mean ± SEM). Scale bar, 100 μm.

Visualizing endogenous NK cells and DCs using Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were adoptively transferred with SNARF-labeled CD8 T cells. A day later, popliteal LNs were harvested, and frozen sections were stained with an anti-B220 Ab and imaged by confocal microscopy. Images were then subjected to spectral unmixing. (A) Individual pseudocolored images showing DCs (YFP-positive cells, pseudocolored in green), NK cells (GFP positive, pseudocolored in red), adoptively transferred T cells (blue), and B cells (B220+ cells, white). (B) Representative confocal image showing that LN NK cells (red) are enriched at the T cell–B cell zone interface. (C) The density of NK cells was compared in the most peripheral layer of the T-cell zone (≤ 100 μm below B cell follicles) or in the rest of the T-cell area (mean ± SEM). Scale bar, 100 μm.

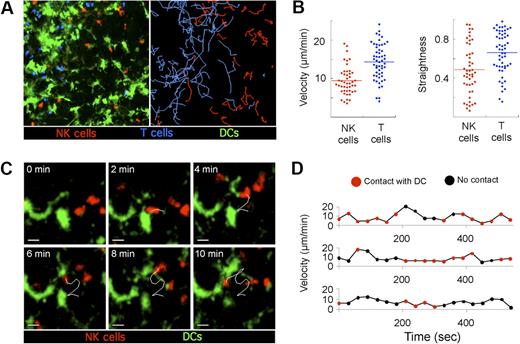

To assess the migration pattern of endogenous NK cells and their interactions with resident DCs under steady state conditions, intact LNs from Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were imaged using 2-photon microscopy. LN NK cells were highly motile (Figure 2A; supplemental Videos 1-2, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article), displaying a mean 3-dimensional velocity of 9.4 μm/minute (Figure 2B). NK cells were only slightly slower than T cells that moved in the same area of the LN at a mean 3-dimensional velocity of 14.3 μm/minute, a value consistent with previous studies.34 Compared with T cells, NK cells also displayed significantly lower straightness indexes, indicative of more constrained trajectories (Figure 2B). Next, we analyzed how NK cells interact with DCs at the steady state. Individual NK cells established numerous short-lived interactions with DCs (< 5 minutes) but were almost never observed forming stable contacts (Figure 2C-D; supplemental Videos 1-2). In summary, LN NK cells exhibited sustained motility in the peripheral T-cell area of LNs at steady state, allowing them to repeatedly contact the network of resident DCs.

Steady state behavior of endogenous NK cells in the LN. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were adoptively transferred with 6 × 106 SNARF-labeled OT-I CD8 T cells. A day later, popliteal LNs were subjected to 2-photon imaging. Time-lapse videos were processed to fully discriminate GFP from YFP signals and were subjected to 3-dimensional cell tracking. (A) A representative image of a time-lapse video (left) with NK cells (red), CD8 T cells (blue), and DCs (green) is shown together with the corresponding trajectories (right). (B) The mean 3-dimensional velocity and the straightness index is plotted for individual NK cells and T cells in the same field of view. Low straightness indexes correspond to constrained trajectories. (C) Dynamic scanning of the DC network by LN NK cells at steady state. Representative time-lapse sequence showing NK cells crawling in the vicinity of the DC network. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Instantaneous velocities of 3 representative NK cells are graphed over time. The period during which NK cells are in contact with the DC network are indicated in red. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Steady state behavior of endogenous NK cells in the LN. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were adoptively transferred with 6 × 106 SNARF-labeled OT-I CD8 T cells. A day later, popliteal LNs were subjected to 2-photon imaging. Time-lapse videos were processed to fully discriminate GFP from YFP signals and were subjected to 3-dimensional cell tracking. (A) A representative image of a time-lapse video (left) with NK cells (red), CD8 T cells (blue), and DCs (green) is shown together with the corresponding trajectories (right). (B) The mean 3-dimensional velocity and the straightness index is plotted for individual NK cells and T cells in the same field of view. Low straightness indexes correspond to constrained trajectories. (C) Dynamic scanning of the DC network by LN NK cells at steady state. Representative time-lapse sequence showing NK cells crawling in the vicinity of the DC network. Scale bar, 10 μm. (D) Instantaneous velocities of 3 representative NK cells are graphed over time. The period during which NK cells are in contact with the DC network are indicated in red. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

LN NK-cell priming after in vivo stimulation with poly I:C

Injection of poly I:C, a synthetic analog of double-stranded RNA, mimics certain aspects of viral infection, including the triggering of NK-cell effector functions. NK-cell activation after in vivo poly I:C treatment is dependent on DCs and is thought to involve direct DC–NK-cell interaction, allowing DC transpresention of IL-15.15,18 We carefully characterized the kinetics of NK-cell activation in vivo after intravenous poly I:C treatment. NK cells were analyzed over time for CD69 expression, granzyme B intracellular content, and IFN-γ production. As shown in supplemental Figure 1, CD69 up-regulation was detected on NK cells as early as 6 hour after injection and was maximal at 24 hours. Intracellular granzyme B expression followed approximately the same kinetics: at 24 hours, 87% of NK cells were granzyme Bhigh. Finally, ex vivo IFN-γ production by NK cells peaked at 6 hours but was largely lost at 24 hours. In summary, a fraction of NK cells were activated within 6 hours of poly I:C injection, and, by 24 hour, most of the NK cells recovered from the LN displayed the hallmark of activated NK cells. A similar phenotype was noted on splenic NK cells (not shown). As expected, poly I:C treatment induced the maturation of LN DCs as shown by increased surface levels of MHC class II, CD86, and IL-15Rα (supplemental Figure 2).

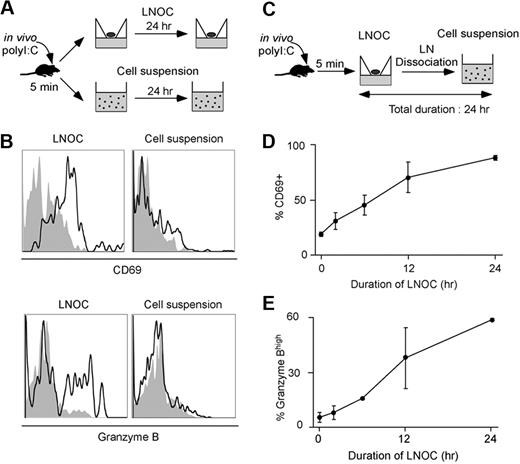

Previous studies have identified LNs as a site for NK-cell recruitment and activation.8,15,35,36 To delineate when and where activation signals are delivered to NK cells in response to poly I:C, we set up a LN organ culture (LNOC) system. B6 mice were injected intravenously with poly I:C, and LNs were harvested 5 minutes later. LNs were either left intact and cultured at the air–liquid interface or were dissociated and cultured as a cell suspension (Figure 3A). NK cells recovered from intact LNs after 24 hour of organ culture displayed the hallmark of NK-cell activation, as determined by CD69 and intracellular granzyme B expression (Figure 3B). This result established that NK-cell activation could uniquely rely on local signal delivered in the LN and did not require soluble factors produced systemically during poly I:C treatment. In contrast, NK cells failed to become activated if the LN was dissociated (Figure 3B). This result underscored the importance of an intact LN microenvironment for NK-cell activation, possibly by favoring cellular interactions and local cytokine production. We took advantage of this observation to assess when activation signals were delivered to NK cells. LNs recovered after 5 minutes of poly I:C treatment were maintained in organ culture for various periods of time and were then dissociated and cultured as a cell suspension so that the total duration of the culture (organ culture + cell suspension) was constant (Figure 3C). Although 6 hours of organ culture were sufficient to detect CD69 up-regulation on a large fraction of NK cells, it was not enough time to observe a significant increase in granzyme B content, which required signals delivered between 6 and 24 hours in the organ culture (Figure 3D-E). Overall, these results suggested that NK-cell priming is not an “all or nothing” phenomenon but rather is the result of the sequential signals delivered within hours in the intact LN microenvironment.

Delineating the timing of NK-cell signal collection for activation. (A) Set up. C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with PBS or 100 μg poly I:C. After 5 minutes, mice were killed, and LNs were immediately harvested. LNs were dissociated or cultured at the air–liquid interface as a LNOC for 24 hours. (B) NK-cell activation occurs in organ culture but not in cell suspension. NK cells were assessed for expression of CD69 and intracellular granzyme B. Histograms were gated on CD3−NK1.1+ cells and correspond to LNs obtained from mice treated with poly I:C (black line) or PBS (filled gray). (C) C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with PBS or 100 μg poly I:C. After 5 minutes, LNs were placed in organ culture for various periods of time and then dissociated and cultured as a cell suspension so that the total duration of the experiment remained fixed at 24 hours. Cells were analyzed for CD69 up-regulation and intracellular granzyme B content by flow cytometry. (D) CD69 up-regulation was graphed as a function of the duration of the LNOC (mean ± SEM). (E) The percentage of NK cells with high intracellular granzyme B content was graphed as a function of the duration of the LNOC (mean ± SEM). Representative of 3 independent experiments.

Delineating the timing of NK-cell signal collection for activation. (A) Set up. C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with PBS or 100 μg poly I:C. After 5 minutes, mice were killed, and LNs were immediately harvested. LNs were dissociated or cultured at the air–liquid interface as a LNOC for 24 hours. (B) NK-cell activation occurs in organ culture but not in cell suspension. NK cells were assessed for expression of CD69 and intracellular granzyme B. Histograms were gated on CD3−NK1.1+ cells and correspond to LNs obtained from mice treated with poly I:C (black line) or PBS (filled gray). (C) C57BL/6 mice were injected intravenously with PBS or 100 μg poly I:C. After 5 minutes, LNs were placed in organ culture for various periods of time and then dissociated and cultured as a cell suspension so that the total duration of the experiment remained fixed at 24 hours. Cells were analyzed for CD69 up-regulation and intracellular granzyme B content by flow cytometry. (D) CD69 up-regulation was graphed as a function of the duration of the LNOC (mean ± SEM). (E) The percentage of NK cells with high intracellular granzyme B content was graphed as a function of the duration of the LNOC (mean ± SEM). Representative of 3 independent experiments.

Visualizing NK-cell–DC interactions during in vivo response to poly I:C

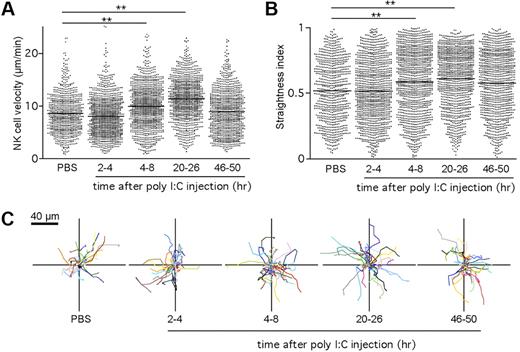

Although it is well established that DCs are required for NK-cell activation after poly I:C stimulation,15,18 the dynamics of NK-cell–DC interactions involved in this process are unknown. To address this issue, we imaged endogenous NK cells and DCs in intact LNs at various time points (from 2 to 48 hours) after poly I:C treatment. Cell velocities and straightness index were quantified for individual NK cells. As depicted in Figure 4A,C and supplemental Video 3, NK cells appeared to remain motile during the course of priming and showed a small but reproducible increase in velocity, starting at 4 hour after injection. NK-cell velocity was maximal at 24 hours, reaching 11.4 μm/minute and returned close to baseline value by 48 hours. In parallel, the NK-cell straightness index increased over time, suggesting that NK cells were less confined (Figure 4B). The increase in cell velocity and straightness observed at 24 hours suggested that NK cells might redistribute in the LN after priming. To test this possibility, we examined the location of NK cells on LN frozen sections. After poly I:C treatment and in contrast to their distribution at steady state, NK cells were equally present in the deep T-cell zone (14 800 ± 4500 cells/mm3) and in the outer T-cell zone (12 600 ± 4100 cells/mm3; supplemental Figure 3).

NK cells maintain a motile behavior during priming in the LN. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were injected intravenously with poly I:C. At various time points, popliteal LNs were imaged by 2-photon microscopy. Mean velocities (A) and straightness indexes (B) were calculated for individual NK cells at various time points after poly I:C injection. Low straightness indexes indicate constrained trajectories. Mean values are shown as black bars. (C) Representative NK-cell trajectories corresponding to 5 minutes of imaging measured at the indicated time period after poly I:C injection. Results are from at least 5 representative videos obtained in 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 (Mann-Whitney test).

NK cells maintain a motile behavior during priming in the LN. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were injected intravenously with poly I:C. At various time points, popliteal LNs were imaged by 2-photon microscopy. Mean velocities (A) and straightness indexes (B) were calculated for individual NK cells at various time points after poly I:C injection. Low straightness indexes indicate constrained trajectories. Mean values are shown as black bars. (C) Representative NK-cell trajectories corresponding to 5 minutes of imaging measured at the indicated time period after poly I:C injection. Results are from at least 5 representative videos obtained in 3 independent experiments. **P < .01 (Mann-Whitney test).

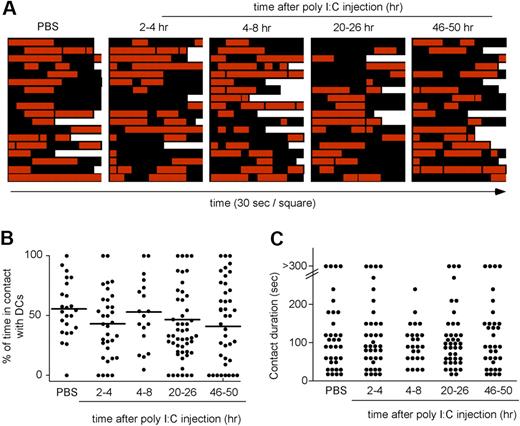

Although these data indicated that NK-cell priming was not associated with NK-cell deceleration, it remained possible that NK-cell motility was modulated in the first 1 to 2 hours that follow poly I:C injection. To test this possibility, Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were subjected to intravital imaging of the popliteal LN, and poly I:C was injected intravenously during image acquisition. As shown in supplemental Figure 4 and supplemental Video 4, NK cells remained motile during the course of the experiment. Finally, we also imaged NK-cell priming in response to a different TLR agonist, LPS, and found again that NK-cell activation proceeded without NK-cell arrest (supplemental Figure 5; supplemental Video 5). Altogether, these results suggested that NK-cell priming did not require the formation of stable NK cell–DC interactions in vivo. To confirm this hypothesis, we examined the pattern of NK cell–DC contacts over time (Figure 5; supplemental Video 3). During the course of NK-cell priming, individual NK cells were found to serially engage DCs, forming contact lasting on average from 1 to 3 minutes. Despite the shortness of individual interactions, the density of resident DCs and the pattern of NK-cell migration implied that NK cells spend 40% to 60% of their time in direct contact with a DC. In summary, NK-cell priming in LNs did not require the formation of stable interactions with DCs. Rather, NK cells had the opportunity to collect signals through their multiple transient contacts with DCs.

Transient interactions between NK cells and the DC network during the course of NK-cell priming. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were injected intravenously with poly I:C. At various time points, popliteal LNs were imaged by 2-photon microscopy. Individual NK cells were analyzed over time for interactions with DCs. (A) Contact histories for individual NK cells. Red squares correspond to time points at which the analyzed NK cell contacted a DC. Black squares correspond to time point at which the NK cells showed no apparent interaction with the DC network. Each square corresponds to a 30-second interval. (B) The percentage of time spent by individual NK cells in contact with DCs is compiled at various time points after poly I:C injection. Mean values are shown as black bars. (C) The duration of individual NK cell–DC contacts is graphed for the various time points analyzed. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Transient interactions between NK cells and the DC network during the course of NK-cell priming. Ncr1GFP/+ × CD11c-YFP mice were injected intravenously with poly I:C. At various time points, popliteal LNs were imaged by 2-photon microscopy. Individual NK cells were analyzed over time for interactions with DCs. (A) Contact histories for individual NK cells. Red squares correspond to time points at which the analyzed NK cell contacted a DC. Black squares correspond to time point at which the NK cells showed no apparent interaction with the DC network. Each square corresponds to a 30-second interval. (B) The percentage of time spent by individual NK cells in contact with DCs is compiled at various time points after poly I:C injection. Mean values are shown as black bars. (C) The duration of individual NK cell–DC contacts is graphed for the various time points analyzed. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

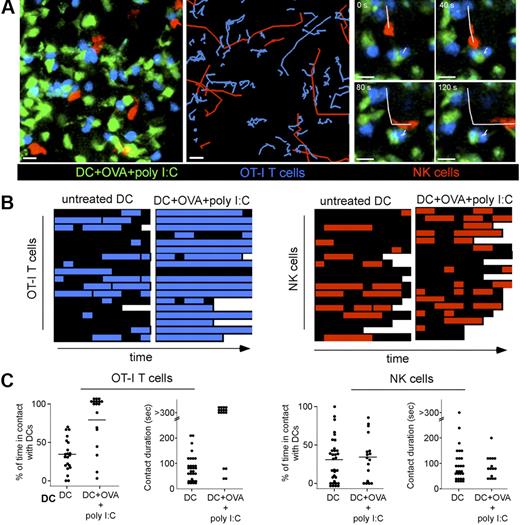

T cells but not NK cells form stable interaction with stimulatory DCs

Next, we directly compared the ability of NK cells and T cells to form stable conjugates with stimulatory DCs in vivo. To this end, we adoptively transferred peptide-pulsed (or unpulsed) DCs and injected them in the footpad of Ncr1GFP/+ recipients in the presence (or absence) of poly I:C. Recipients were also transferred with naive OT-I CD8 T cells. Two-photon imaging of popliteal LNs was performed to compare DCs interactions with NK cells and CD8 T cells (Figure 6A). NK cells and CD8 T cells were highly motile in the presence of untreated DCs (Figure 6B-C; supplemental Video 6). As expected from previous studies,37 CD8 T cells and peptide-pulsed DCs injected in the presence of poly I:C were engaged in long-lasting interactions that did not dissociate during the duration of the experiment (Figure 6A,B-C left; supplemental Video 7). In sharp contrast, NK cells remain motile and established short-lived contacts with the same DC population (Figure 6A,B-C right; supplemental Video 7). Similar differences were obtained when NK cells and CD4 T cells bearing the HY-specific Marilyn TCR were analyzed for interactions with peptide-pulsed DCs in the presence of poly I:C (supplemental Figure 6; supplemental Video 8). Finally, the lack of NK cells that arrest on activated DCs was not an indirect effect of poly I:C injection because it was also observed when we transferred DCs that were isolated from an animal injected with poly I:C 2 hours before and washed extensively (supplemental Video 9).

T cells and NK cells use different modes of interactions with stimulatory DCs. Ncr1GFP/+ mice were adoptively transferred with SNARF-labeled naive OT-I CD8 T cells. Unpulsed or peptide-pulsed DCs purified from CD11c-YFP mice were injected in the footpad of recipients in the presence or absence of poly I:C. Popliteal LNs were subjected to 2-photon imaging 20 hours after DC transfer. (A left) Representative image showing DCs (green), NK cells (red), and T cells (blue). NK cells and T cells trajectories in the presence of DCs pulsed with OVA peptide and poly I:C (middle). The figure shows that T cells but not NK cells are arrested, as reflected by their highly constrained trajectories. (Right) Image sequence showing the same peptide-pulsed DC forming a stable contact with 2 OT-I T cells and a transient interaction with an NK cell. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Individual OT-I T cells and NK cells were assessed for their interactions with peptide-pulsed DCs in the presence of poly I:C. The periods during which T cells and NK cells are in contact with a DC are colored in blue and red, respectively. Each square corresponds to a time interval of 30 seconds. (C) Graph shows the overall percentage of time spent by individual T cells (left) or NK cells (right) in contact with the indicated DC populations. Mean values are shown as black bars. The duration of individual contacts is also plotted for T cell–DC (left) and NK cell–DC interactions (right).

T cells and NK cells use different modes of interactions with stimulatory DCs. Ncr1GFP/+ mice were adoptively transferred with SNARF-labeled naive OT-I CD8 T cells. Unpulsed or peptide-pulsed DCs purified from CD11c-YFP mice were injected in the footpad of recipients in the presence or absence of poly I:C. Popliteal LNs were subjected to 2-photon imaging 20 hours after DC transfer. (A left) Representative image showing DCs (green), NK cells (red), and T cells (blue). NK cells and T cells trajectories in the presence of DCs pulsed with OVA peptide and poly I:C (middle). The figure shows that T cells but not NK cells are arrested, as reflected by their highly constrained trajectories. (Right) Image sequence showing the same peptide-pulsed DC forming a stable contact with 2 OT-I T cells and a transient interaction with an NK cell. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Individual OT-I T cells and NK cells were assessed for their interactions with peptide-pulsed DCs in the presence of poly I:C. The periods during which T cells and NK cells are in contact with a DC are colored in blue and red, respectively. Each square corresponds to a time interval of 30 seconds. (C) Graph shows the overall percentage of time spent by individual T cells (left) or NK cells (right) in contact with the indicated DC populations. Mean values are shown as black bars. The duration of individual contacts is also plotted for T cell–DC (left) and NK cell–DC interactions (right).

Altogether these experiments have shown that NK cells and CD4 or CD8 T cells adopt distinct modes of interaction with stimulatory DCs and have implied that NK cells can collect activation signals while maintaining their active crawling behavior.

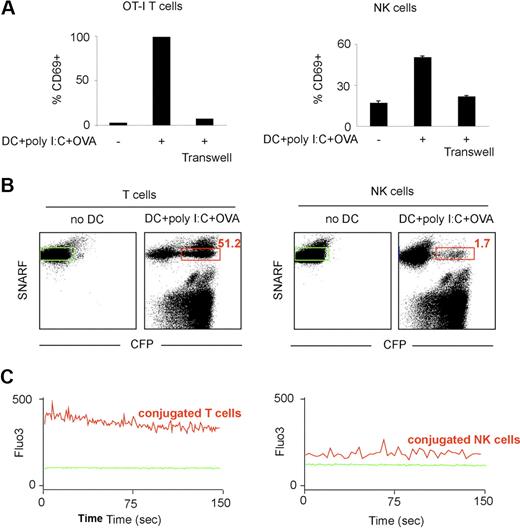

T cells but not NK cells exhibit strong calcium response upon interactions with stimulatory DCs

It has been shown that T-cell arrest upon antigen-recognition can be dictated by calcium signals. We therefore compared calcium signals in NK cells and T cells upon in vitro incubation with stimulatory DCs. In vitro, DCs isolated from a poly I:C–treated mouse and pulsed with the OVA peptide were stimulatory for both NK cells and CD8 OT-I T cells as detected by CD69 up-regulation (Figure 7A). As expected from previous studies, activation did not occur when NK cells (and obviously T cells) were separated from DCs with a semipermeable membrane, reflecting the requirement for direct cellular interactions or close proximity in this process (Figure 7A). Next, we simultaneously monitored the efficiency of cell conjugation with DCs and the triggering of a calcium response. To this end, NK cells or OT-I CD8 T cells were loaded with the SNARF dye and with Fluo3, a calcium-sensitive dye, and incubated with OVA-pulsed DCs isolated from a poly I:C–treated CFP-expressing mouse. In good agreement with our in vivo data, more than one-half of OT-I T cells (52%) but only 2% of NK cells formed, with these stimulatory DCs, conjugates that were stable enough to be detected by flow cytometry (Figure 7B). We then assessed calcium signals in T cells (or NK cells) conjugated with a DC. Strong intracellular calcium signals were detected in T cells forming conjugates with stimulatory DCs (Figure 7C). In contrast, the small subset of NK cells that formed conjugates with DCs showed only a minor elevation in Fluo3 fluorescence compared with untreated NK cells, a small shift that may at least partly be accounted for by the autofluorescence of the conjugated DC (Figure 7C; data not shown) and represented less than 20% of the fluorescent signal seen with T cells. Although small and transient calcium elevation may not be detected by our approach, substantial differences in the calcium responses of NK cells and T cells in contact to stimulatory DCs provide a plausible explanation for their distinct modes of interaction.

T cells but not NK cells exhibit strong calcium signals in the presence of stimulatory DCs. (A) OT-I T cells or NK cells were cultured alone or with OVA peptide-pulsed DCs purified from poly I:C-treated mice (together or separated by a transwell). After 24 hours, CD69 up-regulation was measured by flow cytometry. (B-C) DCs were purified from poly I:C-treated transgenic mice expressing CFP and pulsed with the OVA peptide. OT-I CD8 T cells or NK cells were loaded with the calcium indicator Fluo3 and the SNARF dye and were either left alone or were incubated with DCs for 1 hour at 37°C. (B) T cells but not NK cells from stable conjugates with stimulatory DCs in vitro. The percentage of T cells (left panel) or of NK cells (right panel) conjugated to a DC is shown in red. (C) Flow cytometry was also used to analyze calcium signals in T cells or NK cells that were conjugated with a DCs at the time of data acquisition (red gate in panel B). The same analysis was performed with T cells or NK cells cultured in the absence of DCs (green gate). Histograms show the Fluo3 fluorescence in T cells or NK cells cultured alone (plain green histograms) or when conjugated to a stimulatory DC.

T cells but not NK cells exhibit strong calcium signals in the presence of stimulatory DCs. (A) OT-I T cells or NK cells were cultured alone or with OVA peptide-pulsed DCs purified from poly I:C-treated mice (together or separated by a transwell). After 24 hours, CD69 up-regulation was measured by flow cytometry. (B-C) DCs were purified from poly I:C-treated transgenic mice expressing CFP and pulsed with the OVA peptide. OT-I CD8 T cells or NK cells were loaded with the calcium indicator Fluo3 and the SNARF dye and were either left alone or were incubated with DCs for 1 hour at 37°C. (B) T cells but not NK cells from stable conjugates with stimulatory DCs in vitro. The percentage of T cells (left panel) or of NK cells (right panel) conjugated to a DC is shown in red. (C) Flow cytometry was also used to analyze calcium signals in T cells or NK cells that were conjugated with a DCs at the time of data acquisition (red gate in panel B). The same analysis was performed with T cells or NK cells cultured in the absence of DCs (green gate). Histograms show the Fluo3 fluorescence in T cells or NK cells cultured alone (plain green histograms) or when conjugated to a stimulatory DC.

Discussion

The present study aimed at identifying the biophysical mode of NK cell–DC interactions in a secondary lymphoid tissue under homeostatic and activating conditions. Two previous studies have relied on adoptively transferred cells to visualize NK cells in LNs. One report described NK cells as being low motile cells (2-3 μm/minute), establishing long-lived interactions with DCs at steady state.27 A second report found that adoptively transferred NK cells that were not isolated through DX5 ligation move more vigorously with a 2-dimentional mean velocity of 6 to 7 μm/minute.28 The use of NCR1GFP/+ mice, in which GFP fluorescence marks all NK cells with high specificity, allowed us to extend these findings by unequivocally identify the migratory pattern of endogenous NK cells. At steady state, NK cells were highly motile, migrating at 9 μm/minute. Compared with T cells, resting NK cells displayed more confined trajectories, suggesting that NK cells and T cells respond to different molecular cues during intranodal migration. Such observation is also consistent with the previous finding that NK cells are selectively enriched in the most peripheral part of the LN T-cell zone, beneath and in between B-cell follicles.27,33 Once activated, NK cells displayed increased velocities and reduced confinement and were redistributed in the T-cell zone.

The pivotal role for DCs to activate NK-cell functions is well established. Whether NK cell–DC communication relies on long-lasting interactions in vivo was unknown, although it has been previously observed that human and mouse NK cells can form stable conjugates with mature DCs in vitro.23,24 Surprisingly, we found that NK cells did not establish long-lived contacts with maturing DCs in vivo. By carefully examining when NK cells perceived signals during their activation and imaging the dynamics of NK cell–DC interactions, we found that NK cells maintained a high motility and only engaged DCs in the form of short and dynamic interactions, typically lasting less than 5 minutes. Previous experiments with a semipermeable membrane5,38 have shown the requirement for direct cell–cell interaction for NK-cell priming by DCs in vitro. In vivo, NK-cell priming has been shown to rely on IL-15 transpresentation by DCs.15,18,21 Elegant experiments that used mixed bone marrow chimeras indicated that in vivo NK-cell activation in response to poly I:C required the same DCs to produce IL-15 and to express IL-15Rα for cytokine transpresentation, implicating again a direct cell contact.18 In the light of all these studies, our results strongly suggest that NK cells are primed through a series of short-lived interactions established with IL-15–transpresenting DCs. Additional signals delivered by DCs or other accessory cells in the form of soluble cytokines that may not require a direct cell contact (but may yet be favored by close proximity) could also potentially contribute to NK-cell priming. In fact, despite the absence of long-lived interaction with DCs, NK cells had ample opportunity to respond to soluble or transpresented cytokines in the vicinity (or on the surface) of DCs; we estimated that NK cells spend approximately 50% of their time in direct contact with the LN DC network.

Similar cellular dynamics were noted when we analyzed NK-cell interactions with adoptively transferred mature DCs. Subcutaneous injection of DCs has been previously shown to result in NK-cell recruitment and activation in the draining LN, which in turn promotes Th1 responses through IFN-γ production.36 In our settings, no stable 3-cell cluster containing NK cells, DCs, and either CD4 or CD8 T cells were observed, indicating that NK cells may not need to interact with T cell–DC conjugates for extended period of time to influence T-cell differentiation.

Overall, our results suggest that NK cells and T cells can use different strategies for efficient activation by DCs, namely the formation of transient versus stable interactions. With respect to T cells, long-lived interactions with DCs are a hallmark of efficient priming even though short T cell–DC contacts can be seen preceding stable contacts or during tolerance induction.37 Several studies have linked T-cell arrest with calcium signals in vitro39,40 and in vivo,41-43 and one report specifically showed that increased intracellular calcium was necessary and sufficient for thymocyte arrest.44 The molecular basis for the different modes of interaction used by T cells and NK cells may lie in the fact that TCR signals are likely to be more effective than cytokine signals at inducing calcium elevation and cell arrest. Indeed, although calcium signals during NK cell–DC contacts in vitro have been documented previously,23,24,45 our side-by-side comparison showed that T cells but not NK cells exhibit a robust calcium response upon interactions with stimulatory DCs. Such a difference in calcium signals may therefore account for the lack of NK-cell arrest during priming. It is also tempting to speculate that the rationale for these divergent strategies may originate from differences in response kinetics and in the frequency of stimulatory DCs. Indeed, during microbial infection only a subset of the activated DCs may present enough pMHC for efficient T-cell priming. Because full T-cell activation requires sustained TCR signaling,46-48 it may be advantageous for T cells to remain in contact for several hours with these rare DCs. NK cells, however, are poised for a rapid response. That NK cells have the ability to become activated while maintaining a migratory behavior may endow them with the ability to efficiently scan a high number of DCs and rapidly integrate the local concentration of cytokine produced and presented by the DC network. The present work was focused on NK-cell activation by conventional DCs responding to TLR agonists, and future studies will be important to address the dynamics of NK-cell interactions with plasmacytoid DCs that can also mediate their activation,49,50 or with target cells through engagement of activating and inhibitory receptors. In a recent study, NK cells established longer contacts with allogeneic B cells than with their syngeneic counterparts, yet the average duration was relatively short, in the range of a few minutes.28 The development of new tools to image signaling events in lymphocytes will help further improve our understanding of the distinct strategies used by T cells and NK cells to collect activation signals in lymphoid tissues.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Albert and E. Robey for helpful comments on the manuscript, and the Plateforme de Cytométrie and the Plateforme d'Imagerie Dynamique, Institut Pasteur, for confocal imaging.

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur, Inserm, Mairie de Paris and a Marie Curie Excellence grant. J.P.D.S. is supported by the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer as an Equipe Labellisée. H.B. is supported by the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale.

Authorship

Contribution: H.B. designed and performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; J.D. and B.B. performed research; O.M. and J.P.D.S. provided vital reagents; and P.B. designed research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Philippe Bousso, Institut Pasteur, G5 Dynamiques des Réponses Immunes, 25 rue du Dr Roux 75724, Paris Cedex 15, France; e-mail: philippe.bousso@pasteur.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal