Abstract

CD56+ human dendritic cells (DCs) have recently been shown to differentiate from monocytes in response to GM-CSF and type 1 interferon in vitro. We show here that CD56+ cells freshly isolated from human peripheral blood contain a substantial subset of CD14+CD86+HLA-DR+ cells, which have the appearance of intermediate-sized lymphocytes but spontaneously differentiate into enlarged DC-like cells with substantially increased HLA-DR and CD86 expression or into fully mature CD83+ DCs in response to appropriate cytokines. Stimulation of CD56+ cells containing both DCs and abundant γδ T cells with zoledronate and interleukin-2 (IL-2) resulted in the rapid expansion of γδ T cells as well as in IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β but not in IL-4, IL-10, or IL-17 production. IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-1β production were almost completely abolished by depleting CD14+ cells from the CD56+ subset before stimulation. Likewise, depletion of CD14+ cells dramatically impaired γδ T-cell expansion. IFN-γ production could also be blocked by neutralizing the effects of endogenous IL-1β and TNF-α. Conversely, addition of recombinant IL-1β, TNF-α, or both further enhanced IFN-γ production and strongly up-regulated IL-6 production. Our data indicate that CD56+ DCs from human blood are capable of stimulating CD56+ γδ T cells, which may be harnessed for immunotherapy.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that initiate and regulate a broad repertoire of immune responses.1,2 Both myeloid and lymphoid DC subsets have been proposed with different developmental origins. DCs link innate and adaptive immunity. In addition to their elaborate capability to activate T cells in an αβ TCR-dependent and MHC- or CD1-restricted fashion,1-4 DCs can also interact with innate lymphocytes such as natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells, and γδ T cells. These innate lymphocytes can trigger DC maturation, and mature DCs, in turn, can activate and expand innate lymphocytes to initiate and modulate adaptive T-cell immunity.5

γδ T cells, which represent less than 10% of human peripheral blood T cells,6 can be classified according to their expression of TCR variable (V) region segments into Vδ1 T cells and Vδ2 T cells, which also differ in their tissue distribution and their antigen specificity.7 In the blood of most healthy persons T cells expressing Vδ2 paired with Vγ9 account for 50% to greater than 90% of all γδ T cells.7 Vδ2 T cells recognize phosphoantigens such as the mevalonate pathway–derived isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP).8,9 IPP is increased in malignant cells, and IPP accumulation can be triggered by pharmacologic inhibition of the IPP-metabolizing enzyme farnesylpyrophosphate synthase using bisphosphonates such as zoledronate or pamidronate.10,11 In contrast, Vδ1 T cells are considered tissue γδ T cells, which are present in intestinal epithelia, in the skin, and may be abundant among tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.12,13 Vδ1 T cells recognize MHC class I chain–related molecules A and B as well as UL-16 binding proteins.7 Some of the Vδ1 T cells have been reported to recognize CD1c.14 Most γδ T cells lack CD4 and CD8 expression, which is in accordance with their MHC-nonrestricted recognition of unconventional antigens.7 Effector function of γδ T cells involves strong cytotoxic activity and cytokine production. Although γδ T cells are predominantly TH1 and produce IFN-γ and TNF-α,7,15 TH2-type γδ T cells have also been described.16,17 Moreover, the importance of interleukin-17 (IL-17)–producing γδ T cells in models of infectious disease, immune-mediated disease and in injury models is increasingly becoming apparent.18 γδ T-cell effector function is controlled by both TCR-dependent and -independent mechanisms, including activating (NKG2D)19 and inhibitory (CD94) receptors.20 During reciprocal interaction between monocyte-derived DCs and γδ T cells, pamidronate-induced γδ T-cell activation has been shown to depend on CD86-mediated costimulation.21 Another APC-derived factor that can affect γδ T-cell activation and expansion is IL-1β.13,22 Reciprocal interactions between γδ T cells and activated macrophages have also been shown to result first in the activation of γδ T cells, which then, in turn, induce macrophage cell death to limit and eventually to down-modulate inflammatory responses.23

Expression of CD56, which can be up-regulated by IL-2,24 has also been correlated with increased effector function. Among NK cells, CD56 bright staining is associated with a high cytokine-producing capacity.25 In conventional αβ T cells, CD56 expression correlates with potent effector function.26 In addition, recent work has shown that CD56+ γδ T cells have increased antitumor effector function compared with their CD56− counterparts.27 These observations collectively suggest that CD56 expression may define a functional subset enriched in effector cells that are equipped with increased cytotoxicity and cytokine-producing capacity. A role of CD56, which is identical with neural cell adhesion molecule,28 in homophilic adhesion (ie, binding to itself) has been shown in the nervous system,29 but it has not been convincingly shown with hematopoietic cells.30 As a consequence, no consensus has emerged on the role of CD56 in T- or NK-cell function.

A population of circulating CD56+ cells expressing high levels of HLA-DR has recently been detected and has been shown to be phenotypically and functionally similar to conventional CD56− DCs.31 Moreover, evidence has been obtained that cells with a very similar phenotype can differentiate from CD14+ monocytes in response to GM-CSF and type 1 interferon (IFN).32 In the present work, we describe circulating CD56+CD14+ cells expressing high levels of HLA-DR and CD86. Freshly isolated, these cells have the appearance of intermediate-sized lymphocytes but spontaneously differentiate in vitro into enlarged DC-like cells with considerable γδ T-cell–stimulatory capacity.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-CD3 (UCHT1-FITC, HIT3a-PE, SK7-PerCP-Cy5.5), anti-CD14 (MϕP9-FITC), anti-CD83 (HB15e-PE), anti-CD86 (FUN-1-FITC), anti–HLA-DR (TU36-PE), anti–TCR-αβ-1 (WT31-FITC), anti–TCR-γδ-1 (11F2-PE) were all from BD Biosciences; anti-CD56 (NKH-1-PE), anti-Vγ9 (IMMU 360-FITC), anti-Vδ2 (IMMU 389-FITC) were from Beckman Coulter; cytokine-neutralizing antibodies were from R&D Systems; anti–TNF-α (28401), anti–IL-1β (8516), anti–IL-12 (24 910); zoledronic acid (zoledronate; Zometa) was from Novartis. Recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukin) was from Novartis. Recombinant human GM-CSF (Leukine) was from Berlex Laboratories; recombinant human IL-4 was from CellGenix. Recombinant human TNF-α and IL-1β were obtained from R&D Systems, and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; Prostin E2) was from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals.

Cell isolation and depletion

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from buffy coats provided by the local Central Institute of Blood Transfusion by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. All donors gave written informed consent to the use of residual buffy coats for research purposes in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CD56+ cells were purified from PBMCs using CD56 microbeads and LS columns. In some experiments, CD56+ cells were depleted of CD14+ cells using CD14 microbeads and LD columns. All reagents were from Miltenyi Biotec, and all procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, with approval from the University Hospital of Innsbruck Review Board.

Phenotypic analysis

For phenotyping, freshly isolated or cultured cells (1-3 × 105) were stained with specific fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies in PBS containing 0.5% FCS and 50 μg/mL human IgG (Octapharma) to block Fc γ receptors. After a 30-minute incubation followed by 2 washes, cells from each sample were analyzed using a FACSCalibur supported with CellQuest acquisition and data analysis software (BD Biosciences). DCs were selectively gated based on their forward/side scatter (FSC/SSC) properties.

Cell culture, stimulation, and expansion

All cell cultures were performed in complete BioWhittaker RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone). For cytokine measurements, CD56+ cells (0.5-1.0 × 106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2 (100 U/mL) either alone or in combination with zoledronate (1-50 μM) in 96-well round-bottomed plates (0.2 mL). After 3 to 5 days supernatants were harvested for cytokine analysis. For neutralizing and blocking assays, cultures were preincubated with specific antibodies (1-10 μg/mL). To assess the role of cell-to-cell contact experiments were performed using 24-well Transwell inserts (Costar) with a diameter of 6.5 mm and a pore size of 0.4 μm to physically separate DCs and γδ T cells. For γδ T-cell expansion, CD56+ cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2 (100 U/mL) either alone or in combination with zoledronate (1 μM) in 48-well plates (1 mL). After 10 to 14 days, cells were collected, counted, and subjected to flow cytometry for the assessment of γδ T-cell frequency. Absolute numbers of γδ T cells in the individual cultures were derived from total cell numbers considering γδ T-cell frequency. Cell morphology (magnification: 20×/10) and aggregation (magnification: 4×/10) in response to stimulation was documented with the use of an Olympus CK2 microscope equipped with a ProgRes CT3 digital camera and ProgRes CapturePro 2.5 Software (Jenoptik).

Cytokine measurements

Levels of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-12p70, IL-10, IL-6, IL-4, IL-2, and IL-1β were assessed on day 5 in culture supernatants with the use of cytometric Cytokine Bead Arrays from BD Biosciences according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were analyzed using the FACSCalibur and the appropriate software from BD Biosciences. IFN-γ levels were regularly confirmed using the Quantikine Immunoassay for human IFN-γ from R&D Systems. IL-17 was measured in culture supernatants using the Quantikine Immunoassay for human IL-17 from R&D Systems.

For intracellular staining of IFN-γ, cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated in 48-well plates (1 mL) in RPMI–10% FCS with IL-2 (100 U/mL) or zoledronate (2 μM) plus IL-2 for 2 days. During the last 3 to 4 hours cells were treated with Brefeldin A (BD Biosciences) and were then harvested, washed, and stained with anti-Vδ2 mAb for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were washed twice and treated with FIX&PERM (An der Grub Bioresearch). Fixed, permeabilized cells were stained with anti–IFN-γ antibody. After 2 more washes, the cells were analyzed with a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences). Lymphocytes were gated by FSC and SSC, and analysis was done on 50 000 acquired events for each sample using BD FACS (fluorescence-activated cell sorting) Diva 6.1.2.

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons were preformed using Student t test. All calculated P values are results of 1-sided tests. A P value equal to or less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Microsoft Excel and SPSS software (SPSS Inc) were used for calculations.

Results

CD56+ subset in human blood contains a CD14+ subpopulation that can differentiate into DC-like cells

We examined CD56+ cells from human peripheral blood and identified a subpopulation of CD14+ cells, which had the appearance of intermediate-sized lymphocytes and were therefore hardly distinguishable from lymphocytes based on scatter properties in flow cytometric analyses (Figure 1A). Arbitrary gating of cell subsets with increasing FSC showed that CD56+CD14+ cells were located in between the main lymphocyte population and a population of CD56high blasts (Figure 1B gate 3-4). CD56high blasts usually consisted of CD3−CD56bright NK cells and CD3+CD56bright γδ T cells (data not shown). Only when CD14 staining was plotted against FSC, this population clearly segregated from lymphocytes (Figure 1C). CD56+ cells represented 8.9% to 20.5% of the PBMCs (n = 21; mean, 14.2%). Among CD56+ cells, the CD14+ cells represented 4.8% to 18.7% (mean, 13%), and, thus, 2% or less of PBMCs. In addition to CD14, this population expressed significant levels of HLA-DR and CD86 (Figure 2 left), suggesting that these cells were APCs.

CD56+ cells from human peripheral blood harbor CD14+ cells, which resemble intermediate-sized lymphocytes. CD56+ cells were isolated from PBMCs using CD56 microbeads and magnetic-activated cell sorting technology. Purified CD56+ cells were stained for CD56 or CD14 and analyzed with a flow cytometer. (A-B) Step-wise arbitrary gating of subsets with increasing FSC identified a CD14+ cell population with scatter properties characteristic of intermediate-sized lymphocytes. (C) Plotting of CD14 expression against FSC resulted in the segregation of the CD14+ population from the lymphocytes. (A,C) Backgating of CD14+ cells (C) in the multicolor mode visualized the CD14+ population in the FSC/SSC histogram within the lymphocyte population (A gray dots). Results shown are from 1 representative donor (n = 21).

CD56+ cells from human peripheral blood harbor CD14+ cells, which resemble intermediate-sized lymphocytes. CD56+ cells were isolated from PBMCs using CD56 microbeads and magnetic-activated cell sorting technology. Purified CD56+ cells were stained for CD56 or CD14 and analyzed with a flow cytometer. (A-B) Step-wise arbitrary gating of subsets with increasing FSC identified a CD14+ cell population with scatter properties characteristic of intermediate-sized lymphocytes. (C) Plotting of CD14 expression against FSC resulted in the segregation of the CD14+ population from the lymphocytes. (A,C) Backgating of CD14+ cells (C) in the multicolor mode visualized the CD14+ population in the FSC/SSC histogram within the lymphocyte population (A gray dots). Results shown are from 1 representative donor (n = 21).

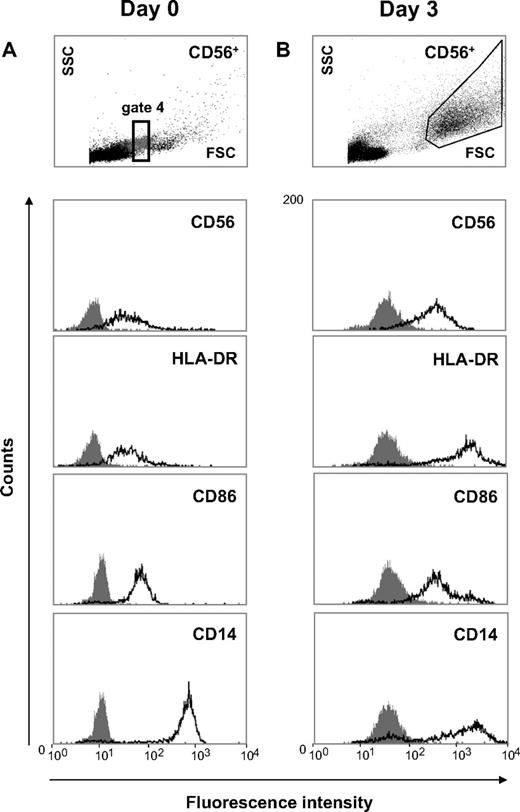

CD56+CD14+ cells spontaneously differentiate into enlarged DC-like cells with increased HLA-DR and CD86 expression. (A) Freshly isolated CD56+ cells were either immediately analyzed for scatter properties (using gate 4 shown in Figure 1) and HLA-DR as well as CD86 expression (day 0), or (B) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were cultured in the absence of exogenous cytokines for 3 days and were then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. During short-term culture CD14+ cells with the appearance of intermediate-sized lymphocytes (top left) spontaneously differentiated into enlarged cells with FSC/SSC properties characteristic of DCs (top right) and (B) with strongly increased HLA-DR and CD86 expression. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with different donors.

CD56+CD14+ cells spontaneously differentiate into enlarged DC-like cells with increased HLA-DR and CD86 expression. (A) Freshly isolated CD56+ cells were either immediately analyzed for scatter properties (using gate 4 shown in Figure 1) and HLA-DR as well as CD86 expression (day 0), or (B) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were cultured in the absence of exogenous cytokines for 3 days and were then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. During short-term culture CD14+ cells with the appearance of intermediate-sized lymphocytes (top left) spontaneously differentiated into enlarged cells with FSC/SSC properties characteristic of DCs (top right) and (B) with strongly increased HLA-DR and CD86 expression. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with different donors.

When CD56+ cells were cultured for 3 days in serum-containing medium but in the absence of exogenous cytokines, these lymphocyte-like cells (Figure 2A gate 4) differentiated into enlarged DC-like cells with FSC/SSC properties characteristic of DCs (Figure 2B large FSC/SSC gate) and with substantially increased HLA-DR and CD86 expression (Figure 2B). Although CD56 expression did not change during culture, the expression of HLA-DR was dramatically up-regulated. For instance, a day 0 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 42 (isotype, 7.9) increased to an MFI of 1649 (isotype, 51) by day 3. Likewise, a CD86 MFI at day 0 of 64 (isotype, 13) increased to an MFI of 472 (isotype, 44). In contrast, CD14 expression was modestly down-regulated (Figure 2). Presence of GM-CSF (800 U/mL) during this short-term culture did not affect the phenotype of the CD56+CD14+ cells (not shown). The development of enlarged DC-like cells also occurred in irradiated CD56+ cell preparations or CD56+ cell preparations treated with Mitomycin C before culturing, indicating that this differentiation process did not require cell proliferation (data not shown).

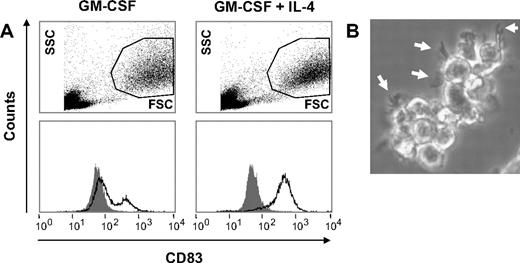

To test whether these CD56+CD14+ cells have the potential to differentiate into conventional myeloid DCs, we cultured them with either GM-CSF alone or GM-CSF plus IL-4 for 3 days, followed by a maturation step induced by TNF-α and PGE2.33-35 Results shown in Figure 3 show that IL-4 was required to induce the full development of DCs with homogenous CD83 expression (Figure 3A) and the typical veiled cytoplasmic extensions (Figure 3B).

CD56+CD14+ cells can be induced to differentiate into fully mature CD83+ DCs. (A) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were cultured for 3 days in either GM-CSF alone (800 U/mL) or in GM-CSF plus IL-4 (500 U/mL). From day 3 to day 5 maturation was induced by the addition of TNF-α (1000 U/mL) and PGE2 (1 μM). Flow cytometric analysis showed that IL-4 was required to allow the development of homogenously CD83+ DCs (B) with the typical cytoplasmic extensions (veils, white arrows).

CD56+CD14+ cells can be induced to differentiate into fully mature CD83+ DCs. (A) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were cultured for 3 days in either GM-CSF alone (800 U/mL) or in GM-CSF plus IL-4 (500 U/mL). From day 3 to day 5 maturation was induced by the addition of TNF-α (1000 U/mL) and PGE2 (1 μM). Flow cytometric analysis showed that IL-4 was required to allow the development of homogenously CD83+ DCs (B) with the typical cytoplasmic extensions (veils, white arrows).

CD56+ subset in human blood is enriched in CD3bright γδ T cells

The CD56+ compartment of human PBMCs, however, not only contained this unexpected APC population but was also enriched in γδ T cells. Almost 40% (range, 20%-57%; mean, 38%) of the CD3+ cells within the CD56+ compartment were γδ T cells (Figure 4 top), which usually represent less than 10% of all peripheral T cells.6,7 The CD3+ cells appeared to consist of 2 subpopulations, which differed in the level of CD3 expression (Figure 4 left). Selective gating showed that the CD3bright cells were mainly γδ T cells (Figure 4 middle), whereas the CD3low cells were mostly αβ T cells (Figure 4 bottom). In some patients, the CD3low but not the CD3bright cells contained both αβ and γδ T cells.

CD56+ cells from human blood are enriched in γδ T cells. (A) Freshly isolated CD56+ cells were stained for CD3 (SK7-PerCP-Cy5.5), αβ TCR (WT31-FITC), and γδ TCR (11F2-PE) and analyzed with a flow cytometer. Using plots of CD3 against FSC, CD3+ cells were gated (left) and then selectively analyzed for αβ TCR or γδ TCR expression (right). Selective gating of CD3bright or CD3low cells (left) identified γδ T cells and αβ T cells, respectively (right). (B) Side-by-side analysis of CD56+ DCs and CD56+ γδ T cells showed that only γδ T cells but not DCs expressed γδ TCR.

CD56+ cells from human blood are enriched in γδ T cells. (A) Freshly isolated CD56+ cells were stained for CD3 (SK7-PerCP-Cy5.5), αβ TCR (WT31-FITC), and γδ TCR (11F2-PE) and analyzed with a flow cytometer. Using plots of CD3 against FSC, CD3+ cells were gated (left) and then selectively analyzed for αβ TCR or γδ TCR expression (right). Selective gating of CD3bright or CD3low cells (left) identified γδ T cells and αβ T cells, respectively (right). (B) Side-by-side analysis of CD56+ DCs and CD56+ γδ T cells showed that only γδ T cells but not DCs expressed γδ TCR.

Brandes et al36 have previously shown that γδ T cells activated with IPP plus IL-2 can acquire all features of professional APCs. We therefore compared in a side-by-side analysis γδ T-cell receptor expression by CD56+ DCs and CD56+ γδ T cells. Whereas γδ T cells exhibited the expected levels of γδ T-cell receptor expression, CD56+ DCs remained negative for γδ T-cell receptor (Figure 4B).

The fact that γδ T cells were enriched in the CD56+ subset of PBMCs (Figure 4) along with the previous observation that 30% to 70% of γδ T cells that expand in response to IPP and IL-2 express CD5627 prompted us to test the ability of CD56+ DCs to activate CD56+ γδ T cells in response to the bisphosphonate zoledronate alone or in combination with IL-2.

CD56+ DCs potently stimulate γδ T-cell expansion and effector function

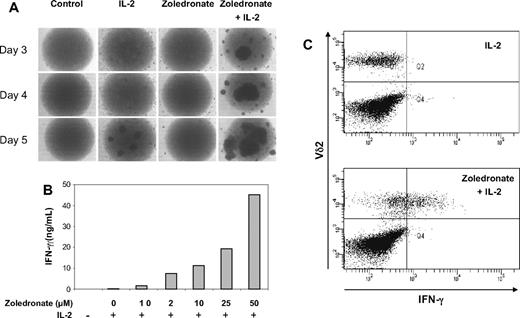

As a first step, we stimulated CD56+ cells with either zoledronate or IL-2 alone or a combination of zoledronate and IL-2. Microscopic examination of cell cultures in round-bottom wells showed a time-dependent increase in cell aggregation indicative of cell activation (Figure 5A). Moreover, the effects of zoledronate plus IL-2 were clearly synergistic and were evident as early as day 3 (Figure 5A). In the presence of a constant IL-2 concentration (100 U/mL), zoledronate as low as 1 μM induced IFN-γ production, and the step-wise increase in zoledronate concentration resulted in a dose-dependent increase in IFN-γ production (Figure 5B). The combined administration of zoledronate and IL-2 resulted in the synergistic induction of high levels of IFN-γ (Figure 5B). Detection of intracellular IFN-γ by flow cytometry confirmed that Vδ2+ cells produced IFN-γ in response to stimulation with zoledronate plus IL-2 but not in response to IL-2 alone (Figure 5C).

Zoledronate and IL-2 promote cellular responses in the CD56+ subset in a synergistic, time- and dose-dependent fashion. (A) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were either left untreated or stimulated with IL-2, zoledronate, or zoledronate plus IL-2 in round-bottomed 96-well plates. Microscopic monitoring of cell cultures from day 3 to day 5 showed cell aggregation as an indicator of cell activation. (B) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2 at 100 U/mL and increasing concentrations of zoledronate. IFN-γ levels determined in culture supernatants on day 5 increased in a dose-dependent fashion (mean values of duplicate cultures). (C) CD56+ cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated for 72 hours with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with zoledronate (2 μM) plus IL-2. Staining of surface Vδ2 and intracellular IFN-γ showed that Vδ2+ cells produced IFN-γ in response to zoledronate plus IL-2 but not in response to IL-2 alone.

Zoledronate and IL-2 promote cellular responses in the CD56+ subset in a synergistic, time- and dose-dependent fashion. (A) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were either left untreated or stimulated with IL-2, zoledronate, or zoledronate plus IL-2 in round-bottomed 96-well plates. Microscopic monitoring of cell cultures from day 3 to day 5 showed cell aggregation as an indicator of cell activation. (B) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were stimulated with IL-2 at 100 U/mL and increasing concentrations of zoledronate. IFN-γ levels determined in culture supernatants on day 5 increased in a dose-dependent fashion (mean values of duplicate cultures). (C) CD56+ cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated for 72 hours with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with zoledronate (2 μM) plus IL-2. Staining of surface Vδ2 and intracellular IFN-γ showed that Vδ2+ cells produced IFN-γ in response to zoledronate plus IL-2 but not in response to IL-2 alone.

TNF-α, another important effector cytokine of γδ T cells, was also induced synergistically by zoledronate plus IL-2 but did not exceed 500 pg/mL (Figure 6). In contrast to IFN-γ and TNF-α, IL-4 (< 20 pg/mL), IL-10 (< 20 pg/mL), IL-12 (< 5 pg/mL), and IL-17 (0.0 pg/mL) were either very low or undetectable (data not shown).

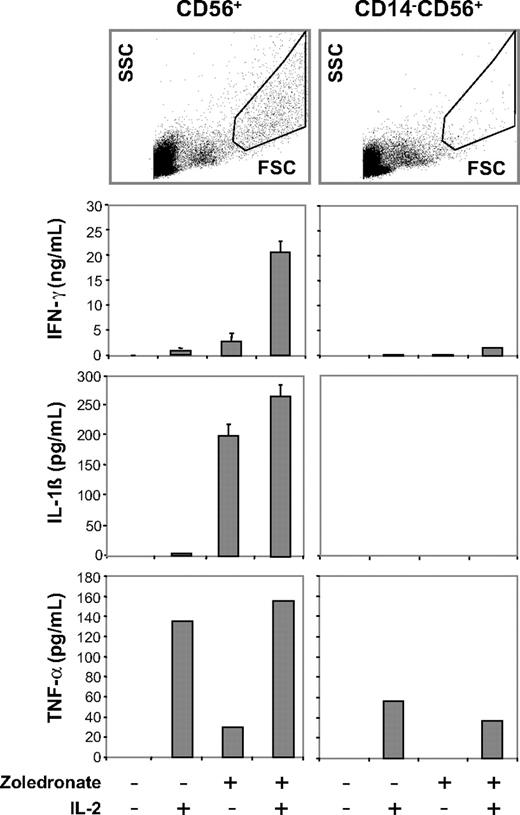

Zoledronate and IL-2 promote cellular responses in the CD56+ subset: abrogation of cytokine responses after depletion of CD14+ cells. CD56+ cells or CD56+ cells depleted of CD14+ cells were either left untreated or stimulated with IL-2, zoledronate, or zoledronate plus IL-2. IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α determined in culture supernatants on day 5 were present in replete cultures but strongly diminished in CD14-depleted cultures. FSC/SCC analysis of control cultures confirmed depletion of the DC population (top). Results shown are combined from 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SD of mean from triplicate cultures.

Zoledronate and IL-2 promote cellular responses in the CD56+ subset: abrogation of cytokine responses after depletion of CD14+ cells. CD56+ cells or CD56+ cells depleted of CD14+ cells were either left untreated or stimulated with IL-2, zoledronate, or zoledronate plus IL-2. IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α determined in culture supernatants on day 5 were present in replete cultures but strongly diminished in CD14-depleted cultures. FSC/SCC analysis of control cultures confirmed depletion of the DC population (top). Results shown are combined from 3 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the SD of mean from triplicate cultures.

Importantly, IL-1β was induced by zoledronate treatment alone and was only modestly further enhanced by IL-2 (Figure 6). IL-1β is considered a monokine produced by monocytes and DCs but not by T cells. Zoledronate-induced IL-1β production could not be observed in CD56+ cells, which had been depleted of CD3+ cells before stimulation (data not shown), suggesting that reciprocal interaction between γδ T cells and DCs present in the CD56+ cell preparation has occurred.21 IL-6, another monokine, was also consistently detected in cultures of CD56+ cells stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2 (≤ 700 pg/mL).

To further examine the role of CD56+ DCs in this system, we tested the response of CD56+ cell preparations that had been depleted of CD14+ cells before stimulation with zoledronate plus IL-2. Side-by-side scatter analysis on day 5 of untreated CD56+ cells and CD56+CD14− cells showed that CD14-depleted cultures lacked cells with the typical FSC/SSC properties of DCs (Figure 6 right), which were, however, abundant in the CD14-replete CD56+ cell cultures (Figure 6 left). Importantly, depletion of CD56+ CD14+ DCs was accompanied by a nearly complete loss of IFN-γ, partial inhibition of TNF-α, and a complete loss of IL-1β (Figure 6) and IL-6 production (not shown). In contrast to the depletion of CD56+CD14+ DCs, physical separation of CD56+ DCs and CD56+ γδ T cells with the use of Transwell inserts still resulted in IFN-γ production, although at much lower levels (not shown).

As an obvious next step, we therefore investigated the role of endogenous IL-1β and TNF-α in IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate plus IL-2 in CD56+ cell preparations. Data shown in Figure 7A show that antibody-mediated neutralization of endogenous IL-1β resulted in pronounced inhibition of IFN-γ production (51%-83.7%; mean, 71.8%; P = .001). Neutralization of TNF-α was less effective and resulted in an inhibition of IFN-γ production that ranged from 31.4% to 45.5% (mean, 39.7%; P = .01; Figure 7A). Because IL-12 has previously been shown to be delivered through the immunologic synapse and may therefore not be detectable in culture supernatants,37 we also used neutralizing anti–IL-12p70 antibodies, which, however, failed to inhibit IFN-γ production (not shown). To further establish the role of IL-1β and TNF-α in this system, we added recombinant IL-1β and TNF-α to cultures of CD56+ cells stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2. Consistent with the strong neutralizing effect of anti–IL-1β (Figure 7A), the addition of recombinant IL-1β significantly enhanced IFN-γ production (Figure 7B left) and induced high levels of IL-6 (Figure 7B right). The addition of recombinant TNF-α also enhanced IFN-γ and IL-6 production but was less effective compared with IL-1β, which is also in accordance with the effects of antibody-mediated neutralization (Figure 7A). The combination of IL-1β and TNF-α was most effective in enhancing IFN-γ and IL-6 production (Figure 7B).

The IFN-γ response induced by zoledronate and IL-2 in the CD56+ subset depends on endogenous IL-1β and TNF-α. (A) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2 in the presence of control (−/−) or neutralizing antibodies against IL-1β or TNF-α. In 3 independent experiments IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate plus IL-2 was strongly inhibited by IL-1β neutralization and to a lesser but still significant extent by neutralization of TNF-α. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between the groups that received control or neutralizing anti–IL-1β or anti–TNF-α antibody according to Student t test for *P < .05, **P < .01. Error bars indicate the SEM from 3 independent experiments. (B) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were stimulated with low-dose zoledronate plus IL-2 in the presence or absence of recombinant IL-1β (1 ng/mL), TNF-α (100 U/mL), or a combination of IL-1β and TNF-α. The levels of IFN-γ and IL-6 in day 5 culture supernatants are strongly up-regulated by IL-1β and to a lesser extent by TNF-α. Data are mean values of duplicate cultures from a representative experiment (n = 3).

The IFN-γ response induced by zoledronate and IL-2 in the CD56+ subset depends on endogenous IL-1β and TNF-α. (A) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2 in the presence of control (−/−) or neutralizing antibodies against IL-1β or TNF-α. In 3 independent experiments IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate plus IL-2 was strongly inhibited by IL-1β neutralization and to a lesser but still significant extent by neutralization of TNF-α. Asterisks indicate statistical significance between the groups that received control or neutralizing anti–IL-1β or anti–TNF-α antibody according to Student t test for *P < .05, **P < .01. Error bars indicate the SEM from 3 independent experiments. (B) CD56+ cells (106/mL) were stimulated with low-dose zoledronate plus IL-2 in the presence or absence of recombinant IL-1β (1 ng/mL), TNF-α (100 U/mL), or a combination of IL-1β and TNF-α. The levels of IFN-γ and IL-6 in day 5 culture supernatants are strongly up-regulated by IL-1β and to a lesser extent by TNF-α. Data are mean values of duplicate cultures from a representative experiment (n = 3).

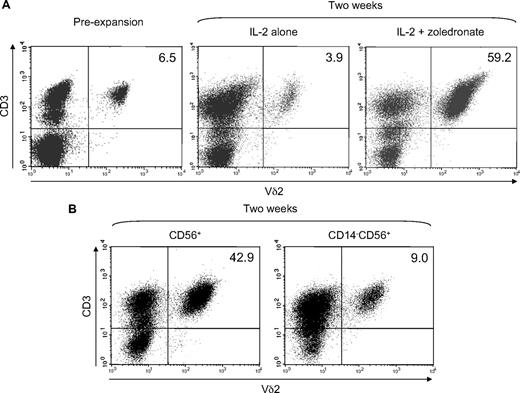

We finally tested the ability of CD56+ DCs to expand γδ T cells in response to low-dose zoledronate (1μM) plus IL-2 compared with IL-2 alone. Freshly isolated CD56+ cells contained 5% to 10% of γδ T cells expressing a Vδ2 TCR (Figure 8A), which is the TCR required for the recognition of zoledronate-induced phosphoantigens.9 However, after 2 weeks of zoledronate-induced, IL-2–supported expansion, Vδ2+ T cells represented 50% to 70% of all cells (Figure 8A) actually resulting in an approximate 50-fold expansion, when the increase in absolute cell number was also considered. In contrast to zoledronate plus IL-2, IL-2 alone unsurprisingly failed to induce effective Vδ2+ T-cell expansion (Figure 8A). To further assess the role of CD56+ DCs, we compared γδ T-cell expansion in the replete CD56+ subset and in CD56+ cells depleted of CD14+ cells before stimulation with zoledronate and IL-2. Figure 8B clearly shows the drop in Vδ2+ T-cell frequency in CD14-depleted cultures of CD56+ cells (right panel) compared with the abundant Vδ2+ T cells in the replete cultures (left panel).

Zoledronate plus IL-2 efficiently expands γδ T cells in the CD56+ cell subset. CD56+ cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with zoledronate (1 μM) plus IL-2. Fresh complete medium containing IL-2 was added every 3 days. After 14 days of expansion, cells were harvested, counted, and analyzed for Vδ2+ T-cell frequency by flow cytometry. (A) Plots of CD3 expression against Vδ2 expression show Vδ2+ T cells in freshly isolated CD56+ cells and show efficient expansion with zoledronate plus IL-2 but not with IL-2 alone. (B) Depletion of CD14+ cells before stimulation with zoledronate and IL-2 resulted in substantially diminished γδ T-cell expansion. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with different donors. Numbers in the upper right quadrants indicate the frequency (in %) of Vδ2+ T cells.

Zoledronate plus IL-2 efficiently expands γδ T cells in the CD56+ cell subset. CD56+ cells (1.5 × 106/mL) were stimulated with either IL-2 alone (100 U/mL) or with zoledronate (1 μM) plus IL-2. Fresh complete medium containing IL-2 was added every 3 days. After 14 days of expansion, cells were harvested, counted, and analyzed for Vδ2+ T-cell frequency by flow cytometry. (A) Plots of CD3 expression against Vδ2 expression show Vδ2+ T cells in freshly isolated CD56+ cells and show efficient expansion with zoledronate plus IL-2 but not with IL-2 alone. (B) Depletion of CD14+ cells before stimulation with zoledronate and IL-2 resulted in substantially diminished γδ T-cell expansion. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with different donors. Numbers in the upper right quadrants indicate the frequency (in %) of Vδ2+ T cells.

When absolute cell numbers were considered γδ T-cell expansion was approximately 10-fold less efficient in the absence of CD56+ DCs. Likewise, γδ T-cell expansion in CD56+ cell preparations from donors containing a rather small DC population (∼ 5%) was significantly less efficient compared with γδ T-cell expansion in CD56+ cell preparations from donors containing a relatively large DC population (≥ 15%; data not shown) further confirming the importance of CD56+ DCs in γδ T-cell expansion induced by zoledronate plus IL-2.

Discussion

In the present work we describe a population of CD56+CD14+ cells from human blood, which resemble intermediate-sized lymphocytes (Figure 1) but have the potential to differentiate into enlarged DC-like cells (Figures 2–3) with potent accessory cell capacity (Figures 5,Figure 6,Figure 7–8). It has been shown previously that DCs can differentiate from CD14+ monocytes in vitro in response to GM-CSF and type 1 IFN.38 Papewalis et al32 have recently shown that more than 50% of these monocyte-derived DCs induced by type 1 IFN were CD56+CD14+ and that these CD56+ IFN-DCs expressed high levels of HLA-DR and moderate to high levels of CD86. Taken together, our data and those provided by Papewalis et al32 suggest that CD56+ DCs in human blood represent the in vivo counterpart of the monocyte-derived IFN-DCs and are thus developmentally and functionally similar to DCs but not to NK cells or γδ T cells. This view is further confirmed by the potential of these cells to effectively develop into CD83+ DCs (Figure 3A) and by the lack of γδ T-cell receptor expression (Figure 4B).

During our analyses of the CD56+ cells we also observed that γδ T cells were enriched in this subset. Although γδ T cells usually represent less than 10% of peripheral blood T cells,6,7 we found that almost 40% of the CD56 + T cells were γδ T cells predominantly with high levels of CD3 expression (Figure 4). Alexander et al27 recently reported that 30% to 70% of γδ T cells expanded with IPP plus IL-2 expressed CD56 and were capable of killing squamous cell carcinoma and other solid tumor cell lines, suggesting that CD56 expression marks γδ T cells with enhanced effector function. The coexistence of DCs along with abundant γδ T cells within the CD56+ subset prompted us to examine the capability of CD56+ DCs to activate and expand CD56+ γδ T cells. We used the bisphosphonate zoledronate to induce the accumulation of the mevalonate pathway–derived IPP, which is one of the major phosphoantigens recognized by Vδ2+ γδ T cells.11 Zoledronate plus IL-2 induced cellular responses, including cell aggregation and cytokine production, in the CD56+ subset in a synergistic, time-, and dose-dependent fashion (Figure 5). IFN-γ clearly dominated the cytokine response, whereas IL-4 was extremely low and IL-17 was completely undetectable. This pattern is consistent with a TH1 type response, which is not surprising,15 although TH2 type γδ T cells have also been described.16,17 Moreover, γδ T cells have recently been identified as a major source of IL-17 in various disease models.18

Along with IFN-γ and TNF-α, which are considered prototypic effector cytokines of γδ T cells,7 the monokine IL-1β was also produced (Figure 6). Three lines of evidence obtained in our study attribute a major role to IL-1β in the regulation of IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate and IL-2 in CD56+ cells. First, depletion of CD14+ cells, which eliminates the CD56+ DCs, resulted in a complete loss of both IL-1β and IFN-γ production (Figure 6). Second, antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-1β diminished IFN-γ production by 70% (Figure 7A). Third, the addition of recombinant IL-1β further enhanced IFN-γ production in cultures of CD56+ cells stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2 (Figure 7B). Our data also indicate that TNF-α plays a role although less prominent. Depletion of CD56+ DCs reduced but did not abolish TNF-α production (Figure 6), and antibody-mediated neutralization of TNF-α resulted only in a 40% inhibition of IFN-γ production (Figure 7A), but exogenous TNF-α was also capable of enhancing IFN-γ production (Figure 7B). Importantly, IL-1β production was induced predominantly by zoledronate alone and only modestly enhanced by the addition of IL-2 (Figure 6). Conversely, TNF-α production was mainly induced by IL-2. Zoledronate-induced TNF-α production was lower than IL-2–induced TNF-α production but strictly depended on the presence of CD56+ DCs (Figure 6). It is conceivable that the 2 different mechanisms of action of zoledronate and IL-2 that induce IL-1β and TNF-α, respectively, converge to create the observed synergistic IFN-γ response (Figures 5–6). TNF-α and IL-1β are prototypic proinflammatory cytokines that are known to efficiently promote DC maturation,34,39 suggesting that CD56+ DCs have to undergo a maturation step to acquire the ability to induce γδ T-cell effector function.5 These observations also suggest that the pronounced responses induced by zoledronate and IL-2 in CD56+ cells are a consequence of reciprocal interactions between CD56+ DCs and CD56+ γδ T cells. The fact that treatment with zoledronate alone could induce IL-1β production in CD56+ cells (Figure 6) and that this IL-1β was completely lost, when CD3+ cells (including γδ T cells) were depleted before stimulation suggests that reciprocal interactions between DCs and γδ T cells are indeed required for IL-1β production and thus for the observed γδ T-cell effector responses. Aside from the known effects of zoledronate on the mevalonate pathway, the direct effects of zoledronate on DCs may also include interference with TLR4-mediated DC activation.40 Physical separation of CD56+ DCs and CD56+ γδ T cells using Transwell inserts, which prevents cell-to-cell contact but allows the exchange of soluble factors, resulted in much lower levels of IFN-γ (data not shown). This finding is in accordance with previous observations.9 In contrast, the absence of CD56+ DCs resulted in the almost complete abrogation of IFN-γ production (Figure 6). Our data thus indicate that CD56+ DCs are important for the initiation of the response, which does not require cell-to-cell contact. However, reciprocal interactions between DCs and γδ T cells during cell-to-cell contact contribute to the strong up-regulation of IFN-γ production.

Although the response induced by zoledronate and IL-2 in CD56+ cells was characterized by high levels of IFN-γ and clearly TH1 biased, we failed to detect IL-12 in culture supernatants. It has been shown previously that NK cell IFN-γ production promoted by mature DCs depends on IL-12.37 However, IL-12 was undetectable in NK cell–DC coculture supernatants. It then turned out that IL-12 was mobilized from preassembled stores in DCs and delivered to NK cells through the immunologic synapse that formed between the 2 cell types. Antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-12 completely abrogated DC-stimulated NK cell IFN-γ production.37 For these reasons we also performed neutralization experiments that used an established blocking antibody that targets IL-12p70. Although this antibody routinely abrogated NK cell IFN-γ production by 85% in our hands, it completely failed to inhibit IFN-γ production induced by zoledronate and IL-2 in CD56+ cells, suggesting that IL-12 is not involved in the regulation of IFN-γ production in CD56+ γδ T cells promoted by CD56+ DCs. One possible explanation for this observation is the fact that many γδ T cells are already TH1 polarized15 and therefore do not depend on IL-12 for IFN-γ production.

CD56+ DCs were not only required for the development of γδ T-cell effector function but also for γδ T-cell expansion. In DC-replete cultures of CD56+ cells, γδ T-cell expansion could easily be induced by zoledronate plus IL-2 (Figure 8A) but was inefficient in DC-depleted cultures of CD56+ cells (Figure 8B). Moreover, in DC-replete cultures of CD56+ cells stimulated with zoledronate plus IL-2, CD56+ DCs disappeared between day 3 and 5 probably because of the development of γδ T-cell cytotoxicity. Egan and Carding23 previously reported that activated macrophages stimulate γδ T cells to acquire cytotoxic activity, which is then also directed against activated macrophages to eventually limit and down-modulate the inflammatory response.

In summary, we have identified CD56+ DC-like cells in human blood, which can activate and expand CD56+ γδ T cells. In our work, we also present a feasible and reliable protocol based on clinical grade reagents for the isolation, activation, and expansion of γδ T cells with enhanced effector function, which may be harnessed for the clinical immunotherapy of cancer.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Reinhold Ramoner for helpful comments in flow cytometry as well as Florina Iliut for cell stainings.

This work was supported by grant 03a of the Kompetenzzentrum Medizin Tirol (KMT; M.T.) and a grant of the COMET K1 Center Oncotyrol (M.T. and N.R.). Oncotyrol is funded by the Federal Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology (BMVIT) and the Federal Ministry of Economics and Labor/Federal Ministry of Economy, Family and Youth (BMWA/BMWFJ) as well as by the Tiroler Zukunftsstiftung (TZS). We further appreciate the participation of the TILAK hospital holding company, who serves as a partner in both the KMT and the Oncotyrol research program.

Authorship

Contribution: G.G. performed all cell culture experiments as well as flow cytometry and data analysis, and edited and proofread the manuscript; H.G. performed all cell culture experiments as well as flow cytometry; A.R. performed all cytokine measurements; W.N. was involved in blood sample preparation and cell enrichment; N.R. performed data analysis and edited and proofread the manuscript; and M.T. designed research, performed data analysis, and wrote, edited, and proofread the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Martin Thurnher, Cell Therapy Unit, Department of Urology, Innsbruck Medical University and K1 Center Oncotyrol, Innrain 66a, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; e-mail: martin.thurnher@i-med.ac.at.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal