Abstract

Administration of human factor VIII (FVIII) to FVIII knockout hemophilia mice is a useful small animal model to study the physiologic response in patients iatrogenically immunized to this therapeutic protein. These mice manifest a robust, T cell–dependent, antibody response to exogenous FVIII treatment, even when encountered through traditionally tolerogenic routes. Thus, FVIII given via these routes elicits both T- and B-cell responses, whereas a control, foreign protein, such as ovalbumin (OVA), is poorly immunogenic. When FVIII is heat inactivated, it loses function and much of its immunogenicity. This suggests that FVIII's immunogenicity is principally tied to its function and not its structure. If mice are treated with the anticoagulant warfarin, which depletes other coagulation factors including thrombin, there is a reduced immune response to FVIII. Furthermore, when mice are treated with the direct thrombin inhibitor, hirudin, the T-cell responses and the serum anti-FVIII antibody concentrations are again significantly reduced. Notably, when FVIII is mixed with OVA, it acts to increase the immune response to OVA. Finally, administration of thrombin with OVA is sufficient to induce immune responses to OVA. Overall, these data support the hypothesis that formation of thrombin through the procoagulant activity of FVIII is necessary to induce costimulation for the immune response to FVIII treatment.

Introduction

Hemophilia affects 1 in 5000 males across all populations.1,2 Standard treatment involves infusions of recombinant or plasma-derived factor VIII (FVIII), but up to one-third of patients form inhibitory antibodies (inhibitors) to functional domains of therapeutic FVIII.3,4 The formation of inhibitors affects patient outcomes, dramatically increases the cost of treatment, and represents the most serious complication to patients treated for hemophilia. Many of the risk factors, including genetic and environmental factors, have been reviewed,4,5 but the reason patients develop an immune response to treatment, in the absence of any adjuvant (also known as “the dirty little secret of immunologists”6,7 ), remains incompletely understood.

The immune response to FVIII is T-cell dependent in humans8-11 and mice.12,13 A typical T cell–dependent antibody response begins when an immature antigen-presenting cell (APC; eg, dendritic cell) encounters a “danger” signal.14 The APC will mature and begin to present high levels of antigen on major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. If a CD4+ T cell recognizes the peptide presented along with costimulatory molecules (eg, B7 molecules and/or cytokines), it can differentiate and provide help for B cells to produce antibodies that recognize the conformational epitopes of that antigen. The first evidence that this antibody response is T-cell mediated came from hemophilic patients who were also infected with HIV.8-11 In these case reports, when patients' T-cell levels decreased as a consequence of the HIV infection, so did their anamnestic response to FVIII. When CD4 counts rose in response to antiretroviral drugs, they again began to form inhibitory antibodies. Other experiments in mice confirmed this mechanism by blocking B7/CD2812 or CD40/CD40L13 costimulatory pathways to prevent inhibitor formation.

FVIII is clinically delivered intravenously and can be given to mice intravenously or intraperitoneally, which are typically considered tolerogenic routes for delivery.15,16 Many historic animal models used this method to induce anergy.15 Why, then, should FVIII induce immunity? Pfistershammer et al17 explicitly asked the question: Does FVIII itself contain danger signals similar to pathogen-associated molecular patterns that are recognized by APCs? They cultured primary cells with FVIII in several conditions and assayed for surface markers, cytokines, and functional responses. They concluded that FVIII does not, by itself, present danger signals.17 Thus, the immunogenicity of FVIII is not the result of intrinsic pathogen-associated molecular pattern content.

Purohit et al18 suspected that, if the native protein does not signal “danger,” perhaps it is the formation of aggregates during the manufacturing process that may explain its immunogenicity. Protein aggregates are known to be more immunogenic than nonaggregated protein,19-21 and manufacturing processes related to viral inactivation (eg, pasteurization) may produce immunogenic neo-antigens.22-24 They artificially induced aggregate formation but found the opposite of what was expected (ie, reduced immune responses to aggregated protein). The conclusion was that aggregate formation is not responsible for FVIII's immunogenicity.18

These observations beg the question: if the FVIII protein itself does not signal “danger” to the immune system, what is the source of the signals leading to costimulation and the formation of inhibitors to FVIII?

We hypothesize that factors downstream of FVIII in the coagulation cascade may be able to drive maturation of APCs to produce costimulatory signals for other lymphocytes. That is, when FVIII is injected, it accelerates the activation of FX, which drives the formation of thrombin leading to the polymerization of fibrin and platelet activation.25 One of these factors may help drive the maturation of local APCs. Thus, we first established that, whereas FVIII is able to induce T-cell responsiveness and antibody formation, a different foreign protein, ovalbumin (OVA), has reduced ability to do so. By heat-inactivating FVIII, we establish that FVIII's immunogenicity is primarily linked to its function. In addition, by inactivating thrombin with the anticoagulants warfarin or hirudin, the immune response is again avoided, indicating a role for thrombin in the gateway that leads to initiation of the immune response to FVIII. Furthermore, FVIII delivery may lead to the production of nonspecific costimulatory signals when mice are simultaneously treated with OVA and FVIII, leading to an anti-OVA response. Finally, to uncouple the immune response from the disease hemophilia, thrombin was administered with OVA to mice; the increased response to OVA indicates that thrombin is sufficient to augment immune responses. Thus, an injection of FVIII potentiates the intrinsic coagulation pathway, leading to thrombin production, which provides “danger” signals to the immune system. We suggest that, in patients with hemophilia, the combination of FVIII, a protein for which central tolerance has not been completely induced, and costimulation, which is triggered by thrombin, induce inhibitor formation. Thus, the function of FVIII is paramount to its immunogenicity.

Methods

Mice

Factor VIII-deficient mice26 (FVIII−/−) were used as the model for hemophilia A. These mice, on a C57Bl/6 background, were originally acquired from the colony of Dr Leon Hoyer at the American Red Cross.12 FVIII−/− mice, backcrossed to a BALB/c background, were the generous gift of Dr David Lillicrap (Queen's University, Kingston, ON).27 We have previously seen that both strains form B-cell and T-cell responses in response to FVIII treatments (J.S., unpublished data, March 19, 2009). All animals were housed and bred in pathogen-free microisolator cages at the animal facilities operated by the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Maryland School of Medicine. The genotypes of hemophilic mice were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction analysis of genomic DNA extracted from tail samples, as described previously.12

Immunologic challenge and assay methods

FVIII.

Highly purified recombinant human FVIII was kindly provided by Dr Birgit Reipert (Baxter Bioscience AG). This full-length, recombinant FVIII was produced and purified without the use of blood-based protein additives as previously described.28,29 The stock solution had an activity of 4410 IU/mL and a concentration of 0.74 mg/mL. Before injection, the stock was diluted to 5 μg/mL in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and a dose of 200 μL (1 μg) was delivered intraperitoneally in accordance with previously published protocols.30 Mice were dosed weekly for 5 weeks to obtain antibody and T-cell responses. Similar results have also been obtained with intravenous injections.12,30

OVA.

EndoGrade Ovalbumin, lyophilized (Profos AG) was reconstituted in PBS to a stock solution of 100 μg/mL. Aliquots were stored frozen and thawed immediately before use. The stock solution was diluted to 5 μg/mL in sterile PBS, and mice received 5 weekly doses of 200 μL (1 μg) OVA intraperitoneally.

FVIII + warfarin.

Warfarin (Sigma-Aldrich) was suspended in peanut oil (Sigma-Aldrich) and mice were treated subcutaneously with 125 μg (∼ 5 mg/kg) 3 days and 1 day before the first and third treatments with FVIII.31,32 FVIII was then administered intraperitoneally. To confirm similar responses with intraperitoneal or intravenous administration, this experiment was repeated as described with intravenous doses of 0.2 μg/mL FVIII (supplemental Figure 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

FVIII + hirudin.

Recombinant hirudin (Hyphen BioMed) was reconstituted in sterile distilled water to a stock concentration of 1 mg/mL. Before injection, FVIII was added to a final concentration of 5 μg/mL and mice received 1 μg FVIII with 200 μg (∼ 10 mg/kg) hirudin.

OVA + thrombin.

Thrombin from bovine plasma (Sigma-Aldrich) was reconstituted at a concentration of 1000 IU/mL, and aliquots were frozen. Before use, OVA and thrombin were diluted in PBS to concentrations of 5 μg/mL and 25 IU/mL, respectively, and mice were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μL (1 μg OVA + 5 IU thrombin). Mice received 5 weekly injections.

FVIII inactivation.

Factor VIII was diluted to 10 μg/mL and inactivated by heating to 56°C for 30 minutes. Residual FVIII activity was determined using a chromogenic kit (CoatTest SP4 FVIII; DiaPharma). This kit uses optimal amounts of Ca2+, phospholipids, and an excess of factors IXa and X, leaving the rate of activation of factor X solely dependent on FVIII concentration. FXa hydrolyses a chromogenic substrate that is read photometrically at 405 nm.

Fluorescence study.

Fluorescence measurements of thermally induced unfolding of FVIII were performed in an SLM 8000-C fluorometer (SLM Instruments) by monitoring the ratio of fluorescence intensity at 370 nm to that at 330 nm with excitation at 280 nm. The temperature was controlled with a circulating water bath programmed to raise the temperature at a rate of 1°C/minute.

Antibody response.

Mice were bled from the orbital venous plexus with heparinized capillary tubes 7 days after the last injection. Anti-FVIII antibody titers were determined using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously30 on plates coated with 100 μL FVIII or OVA at a concentration of 1 μg/mL. The concentrations of anti-FVIII antibodies were estimated from a standard curve calculated using A2- (mAb413) and C2-specific (ESH4; American Diagnostica) monoclonal antibodies. For anti-OVA responses, concentrations were measured with a monoclonal anti-OVA antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). Comparing polyclonal antibody responses with different proteins (eg, FVIII vs OVA), antibody titers are shown as endpoint dilutions because we have seen that different monoclonal antibodies often have distinct binding affinities and can yield disparate standard curves to the same protein (J.S., unpublished data, May 19, 2006). Thus, endpoint dilutions are more appropriate for comparing immune responses to different antigens.

T-cell response.

Thymidine (3H) incorporation and T-cell proliferation assays were performed as previously described.30 Briefly, splenic T cells from individual mice were cultured in 96-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) with dilutions of antigen in RPMI 1640 with 2% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% hemophilic mouse serum. After 48 hours, 3H-thymidine was added and the cultures were harvested at 72 hours. The mean counts over 3 minutes from quadruplicate wells were calculated and the background subtracted for statistical calculations. Background levels (ie, counts without antigen) are typically less than 2000 counts.

Thrombin formation.

Qualitative data on thrombin formation were obtained using a commercially available ELISA-based assay (Enzygnost TAT micro; Siemens) adapting protocols that have been described previously.33 Briefly, thrombin complexes with antithrombin III quickly after it is formed, and levels of this complex can be found circulating in the blood and used as a marker for thrombin formation. Groups of mice were injected with FVIII intravenously (0.2 μg), FVIII intraperitoneally (1 μg), or PBS (intravenously or intraperitoneally) as control. A single mouse was bled at different time intervals and plasma samples were assayed following the vendor's recommendations. The values from the PBS-treated control were subtracted from the FVIII-treated mice to calculate the effect of FVIII treatment on thrombin formation.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, the data are expressed as the mean plus or minus SEM. To compare antibody concentrations between experimental groups an unpaired Student t test was used. To compare trends in T-cell proliferation analysis a 2-factor analysis of variance without replication was used.

Results

FVIII is more immunogenic than OVA without adjuvant

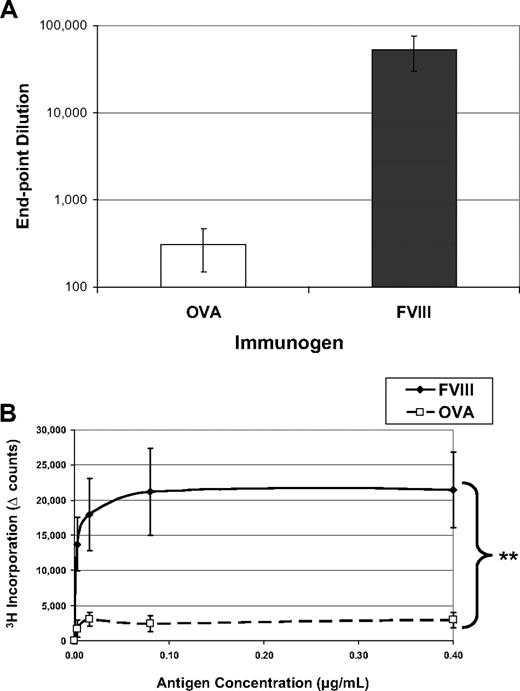

Immunologists have long considered intravenous or intraperitoneal administration of an antigen in saline, in the absence of adjuvant, a tolerogenic route of delivery.15,16 One might expect that T-cell anergy can be induced by delivery of an antigen in the absence of any “danger” signals (eg, adjuvant) that could lead to up-regulation of costimulatory molecules. Indeed, as shown in Figure 1, when hemophilic mice are exposed to 5 weekly injections of OVA, they produce reduced amounts of antibodies to the “foreign” protein and their T cells do not form recall responses in an in vitro proliferation assay. However, when these mice are similarly treated with FVIII, they mount a robust, significantly higher antibody response with average titers to FVIII more than 50 000. In addition, they form significant T-cell responses, measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Both of these proteins would be considered foreign to the mouse, yet the animals selectively respond to FVIII treatment in these experiments.

FVIII is more immunogenic than is OVA. FVIII−/−/BALB/c mice received 5 weekly injections of 1 μg FVIII intraperitoneally (n = 6) or 1 μg OVA intraperitoneally (n = 6). This experiment has been repeated at least 5 times, and representative results are reported here. One week after the final injection, peripheral blood was collected for ELISA analysis and splenocytes were stimulated in vitro for proliferation analysis. (A) Serum samples were assayed on ELISA plates that had been coated with either FVIII or OVA. To compare responses to different proteins, the endpoint dilution is calculated as the highest dilution that maintains a reading twice background. The immunogens are indicated on the x-axis and the titers versus the same antigen on the y-axis. The mean values for the mice treated with OVA (308 ± 106) were more than 2 logs decreased from the mice treated with FVIII (53 000 ± 23 000). (B) Splenocytes were processed into a single-cell suspension and assayed in a thymidine (3H) incorporation assay described previously. T cells from FVIII-treated mice proliferated in response to coculture with FVIII antigen, whereas cells from OVA-treated mice respond poorly to OVA. The background counts (∼ 2000) have been subtracted (Δ counts), and the difference between the groups was highly significant (**P = .004).

FVIII is more immunogenic than is OVA. FVIII−/−/BALB/c mice received 5 weekly injections of 1 μg FVIII intraperitoneally (n = 6) or 1 μg OVA intraperitoneally (n = 6). This experiment has been repeated at least 5 times, and representative results are reported here. One week after the final injection, peripheral blood was collected for ELISA analysis and splenocytes were stimulated in vitro for proliferation analysis. (A) Serum samples were assayed on ELISA plates that had been coated with either FVIII or OVA. To compare responses to different proteins, the endpoint dilution is calculated as the highest dilution that maintains a reading twice background. The immunogens are indicated on the x-axis and the titers versus the same antigen on the y-axis. The mean values for the mice treated with OVA (308 ± 106) were more than 2 logs decreased from the mice treated with FVIII (53 000 ± 23 000). (B) Splenocytes were processed into a single-cell suspension and assayed in a thymidine (3H) incorporation assay described previously. T cells from FVIII-treated mice proliferated in response to coculture with FVIII antigen, whereas cells from OVA-treated mice respond poorly to OVA. The background counts (∼ 2000) have been subtracted (Δ counts), and the difference between the groups was highly significant (**P = .004).

Heat-inactivated FVIII has an altered morphology, reduced activity, and is less immunogenic than native, fully functional FVIII

We hypothesized that perhaps FVIII's immunogenicity is derived from its function rather than its structure. To test this hypothesis, mice were treated with native FVIII or an equal dose of heat-inactivated protein to determine whether its immunogenicity is linked to its procoagulant function. FVIII was heat inactivated for 30 minutes at 56°C, which is known to diminish clotting activity.34 Inactivation is typically performed at physiologic concentrations (0.2 μg/mL), but in vitro assays and preparations for in vivo injections routinely require higher concentrations. Figure 2A shows that activity is completely lost even at concentrations approaching 100 μg/mL. We further characterized the heated product by comparing its fluorescence-detected melting curve to that of native FVIII (Figure 2B). In this experiment, FVIII samples were heated in a fluorometer monitoring the ratio of fluorescence intensity at 370 nm to that at 330 nm as a measure of the spectral shift that accompanies their thermally induced unfolding. The native FVIII sample exhibited a sigmoidal transition between 46°C and 66°C reflecting the distribution of the folded and unfolded protein in this temperature range. The heat-treated FVIII sample also exhibited a sigmoidal transition in the same temperature range; however, the magnitude of this transition was approximately one-third of that observed for native FVIII, indicating that, on average, one-third of the FVIII domains retained their native conformation after treatment with heat.

Characterization of heat-inactivated FVIII. (A) FVIII can be inactivated by heating to 56°C for 30 minutes, and the activity level can be measured using a chromogenic FXa substrate that can be read at A405. This graph demonstrates that preparations of FVIII can be heat-inactivated at concentrations as high as 100 μg/mL. (B) FVIII samples were heated in a fluorometer monitoring the ratio of fluorescence intensity at 370 nm to that at 330 nm with 280 nm excitation. Both the native and heated FVIII samples exhibit a sigmoidal transition between 46°C and 66°C, reflecting the distribution of the folded and unfolded protein in this temperature range. From this plot, it can be inferred that approximately one-third of the B-cell epitopes in the heat-inactivated FVIII are in their native conformation because the magnitude of the shift of the heat-inactivated FVIII is approximately one-third of the magnitude of the shift of the native, untreated FVIII. (C) ELISA plates were coated with either native or heat-inactivated FVIII for analysis of B-cell epitopes. The primary antibodies in this assay were monoclonals that bind to known domains of the native FVIII protein. If the antibodies were also able to bind heat-inactivated FVIII, then they have been described as binding stable domains. If the antibody cannot bind heat-inactivated FVIII, then its epitope has been lost during heating. This figure depicts a drawing of FVIII and its domains. Each monoclonal antibody used has been listed under the domain it binds. If the antibody binds a stable epitope, then it is labeled in black; if the epitope was lost during heating, then the name is labeled in gray. These data correlate with the fluorescence experiment because approximately one-third of the antibodies bind stable B-cell epitopes. (D) Five FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice were immunized with native FVIII, and proliferation assays were performed to compare the profile when cells are stimulated, in vitro, with native or heat inactivated FVIII. There is no significant difference between T-cell recall responses to native or heat-inactivated FVIII, indicating that heating does not alter uptake and presentation.

Characterization of heat-inactivated FVIII. (A) FVIII can be inactivated by heating to 56°C for 30 minutes, and the activity level can be measured using a chromogenic FXa substrate that can be read at A405. This graph demonstrates that preparations of FVIII can be heat-inactivated at concentrations as high as 100 μg/mL. (B) FVIII samples were heated in a fluorometer monitoring the ratio of fluorescence intensity at 370 nm to that at 330 nm with 280 nm excitation. Both the native and heated FVIII samples exhibit a sigmoidal transition between 46°C and 66°C, reflecting the distribution of the folded and unfolded protein in this temperature range. From this plot, it can be inferred that approximately one-third of the B-cell epitopes in the heat-inactivated FVIII are in their native conformation because the magnitude of the shift of the heat-inactivated FVIII is approximately one-third of the magnitude of the shift of the native, untreated FVIII. (C) ELISA plates were coated with either native or heat-inactivated FVIII for analysis of B-cell epitopes. The primary antibodies in this assay were monoclonals that bind to known domains of the native FVIII protein. If the antibodies were also able to bind heat-inactivated FVIII, then they have been described as binding stable domains. If the antibody cannot bind heat-inactivated FVIII, then its epitope has been lost during heating. This figure depicts a drawing of FVIII and its domains. Each monoclonal antibody used has been listed under the domain it binds. If the antibody binds a stable epitope, then it is labeled in black; if the epitope was lost during heating, then the name is labeled in gray. These data correlate with the fluorescence experiment because approximately one-third of the antibodies bind stable B-cell epitopes. (D) Five FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice were immunized with native FVIII, and proliferation assays were performed to compare the profile when cells are stimulated, in vitro, with native or heat inactivated FVIII. There is no significant difference between T-cell recall responses to native or heat-inactivated FVIII, indicating that heating does not alter uptake and presentation.

To determine which epitopes were lost and which were retained after heating, we used an array of fully characterized anti-FVIII monoclonal antibodies (a gift of Dr Pete Lollar, Emory University, Atlanta, GA). In this assay, ELISA plates are coated with either native or heat-inactivated FVIII. All of the monoclonal antibodies bind to native FVIII. If an antibody is also able to bind heat-inactivated FVIII, we assume that the epitope/domain to which it is directed was retained after heating. If an antibody can bind the native, but not the heated FVIII, then that epitope has been lost (Figure 2C). Notably, epitopes within the immunodominant C2 domain, which has active sites that interact with von Willebrand factor, phospholipids, and activated factor X,35 were completely altered. Other domains were partially maintained though the overall protein was rendered inactive as measured by in vitro activity assays. One concern may be that, if the protein is altered, APCs may not be able to sufficiently process and present it. Thus, we immunized 5 mice with native FVIII and measured their ability to respond to either native or inactivated FVIII. Both antigens elicited similar proliferation profiles; no difference was seen as measured by T-cell proliferative responses (Figure 2D). This result is expected because T-cell epitopes are linear peptides, which would not be altered with heat inactivation. Moreover, it confirms that inactivation does not alter uptake or presentation.

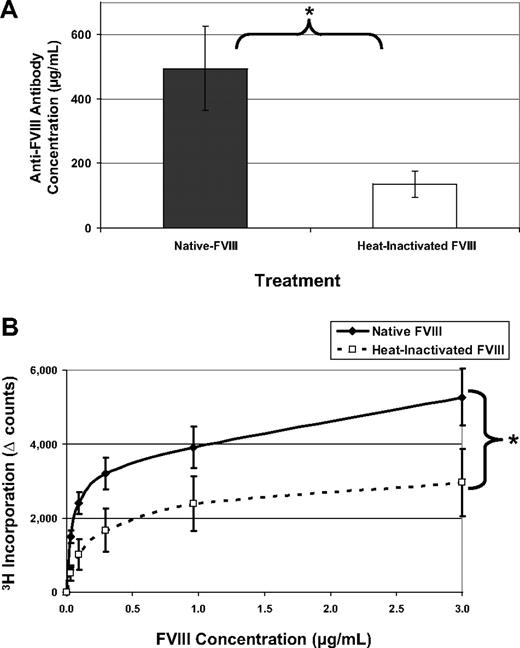

When mice were treated with 5 doses of native FVIII over 5 weeks, they respond with a mean antibody concentration of 495 μg/mL serum. However, treatment with inactive FVIII leads to a significantly lower antibody response (Figure 3A). The corresponding T-cell response (Figure 3B) also indicates a reduction in the overall immunogenicity of inactive FVIII. To determine whether mice treated with inactivated FVIII responded to neo-epitopes formed during heating, ELISA plates were also coated with heat-inactivated FVIII. Overall, titers to heated FVIII were lower in both groups, and the significant trend was maintained (data not shown). A lower titer in the group treated with inactivated FVIII confirms that these mice did not respond to neo-epitopes. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that FVIII must be functional to elicit a maximal immune response.

Heat-inactivated FVIII has reduced immunogenicity. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 intraperitoneal injections of either 1 μg native-FVIII (n = 7) or 1 μg heat-inactivated FVIII (n = 7) and were bled 7 days after the last injection. This experiment was repeated at least 4 times, and representative results are reported here. (A) One week after the last injection, mice were bled and serum samples were analyzed by ELISA. Antibody concentrations were calculated based on standard curves using monoclonal antibodies of known concentration. Native FVIII is highly immunogenic with mean antibody concentrations of 495 ± 131 μg/mL, whereas the inactivated form is less immunogenic at 136 ± 41 μg/mL (*P = .011). (B) Splenocytes were processed into a single-cell suspension and assayed for 3H incorporation as previously described. T cells from native FVIII-treated mice proliferated in response to FVIII, whereas the recall response from mice immunized with heated FVIII was significantly lower (*P = .015).

Heat-inactivated FVIII has reduced immunogenicity. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 intraperitoneal injections of either 1 μg native-FVIII (n = 7) or 1 μg heat-inactivated FVIII (n = 7) and were bled 7 days after the last injection. This experiment was repeated at least 4 times, and representative results are reported here. (A) One week after the last injection, mice were bled and serum samples were analyzed by ELISA. Antibody concentrations were calculated based on standard curves using monoclonal antibodies of known concentration. Native FVIII is highly immunogenic with mean antibody concentrations of 495 ± 131 μg/mL, whereas the inactivated form is less immunogenic at 136 ± 41 μg/mL (*P = .011). (B) Splenocytes were processed into a single-cell suspension and assayed for 3H incorporation as previously described. T cells from native FVIII-treated mice proliferated in response to FVIII, whereas the recall response from mice immunized with heated FVIII was significantly lower (*P = .015).

Warfarin inhibits coagulation and reduces the immune response to FVIII

To more completely explore the coagulation factors activated by FVIII and their role in its immunogenicity, we treated mice with native FVIII while preventing normal coagulation using the anticoagulant warfarin. Warfarin is a vitamin K antagonist that interferes with the vitamin K conversion cycle and synthesis of clotting factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X.36 We hypothesized that, if FVIII triggered an immune response through its procoagulant function, then by inactivating other necessary factors, we would again reduce the immune response. In this experiment, mice were pretreated with warfarin. When they were challenged, with FVIII, we found the group that was pretreated with warfarin had significantly reduced antibody (Figure 4A) and T-cell responses (Figure 4B). This experiment was repeated using intravenous rather than intraperitoneal injections. Supplemental Figure 1 confirms that the trends in the immune response are the same regardless of intraperitoneal or intravenous administration. For consistency, however, the intraperitoneal route of injection was used in all the experiments.

Warfarin prevents the initiation of an immune response to FVIII. FVIII−/−/BALB/c mice were pretreated with warfarin (n = 6) or PBS (n = 7) before the first and third of 5 intraperitoneal injections of 1 μg FVIII. This experiment was repeated twice, and representative data are shown. Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response (582 ± 232 [FVIII] vs 101 ± 24 μg/mL [FVIII + warfarin]; *P = .042) and (B) splenic T cells from the mice treated with FVIII or FVIII + warfarin were assayed for the response to FVIII (**P = .002). These data indicate that other coagulation factors besides FVIII are probably necessary for initiation of the immune response.

Warfarin prevents the initiation of an immune response to FVIII. FVIII−/−/BALB/c mice were pretreated with warfarin (n = 6) or PBS (n = 7) before the first and third of 5 intraperitoneal injections of 1 μg FVIII. This experiment was repeated twice, and representative data are shown. Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response (582 ± 232 [FVIII] vs 101 ± 24 μg/mL [FVIII + warfarin]; *P = .042) and (B) splenic T cells from the mice treated with FVIII or FVIII + warfarin were assayed for the response to FVIII (**P = .002). These data indicate that other coagulation factors besides FVIII are probably necessary for initiation of the immune response.

FVIII's immunogenicity is linked to its ability to elicit thrombin formation

Treatment with FVIII can lead to the amplification of the intrinsic arm of the coagulation cascade. Of the factors that are generated, thrombin was recognized for its proinflammatory “adjuvanticity” in addition to its procoagulant function.37 In addition, the previous experiment with warfarin implicated thrombin as a probable candidate for initiating the immune response to FVIII. To selectively interfere with thrombin activity, we used the direct thrombin inhibitor, hirudin, which forms very tight, noncovalent complexes with thrombin.38 A dose of 200 μg/mouse (∼ 10 mg/kg) was used because it is the minimal dose others have shown to significantly increase activated partial thromboplastin time and thrombin time in the mouse.39 As shown in Figure 5, the B- and T-cell responses to FVIII are reduced when mice were treated simultaneously with FVIII and hirudin compared with standard treatment with FVIII only. We also could not detect any nonspecific, toxic, suppressive effects of hirudin in terms of inhibition of mitogenic stimulation of T cells (supplemental Figure 2).

Hirudin inactivates thrombin and reduces the immunogenicity of FVIII. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 intraperitoneal injections of 1 μg FVIII (n = 5) only or 1 μg FVIII with 200 μg hirudin (n = 5). This experiment was repeated twice, and representative results are reported here. Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response (515 ± 168 [FVIII] vs 134 ± 16 [FVIII + hirudin] μg/mL; *P = .02) and (B) splenic T cells were assayed for the response to FVIII (*P < .002). These data indicate that thrombin is necessary for initiation of the immune response to FVIII.

Hirudin inactivates thrombin and reduces the immunogenicity of FVIII. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 intraperitoneal injections of 1 μg FVIII (n = 5) only or 1 μg FVIII with 200 μg hirudin (n = 5). This experiment was repeated twice, and representative results are reported here. Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response (515 ± 168 [FVIII] vs 134 ± 16 [FVIII + hirudin] μg/mL; *P = .02) and (B) splenic T cells were assayed for the response to FVIII (*P < .002). These data indicate that thrombin is necessary for initiation of the immune response to FVIII.

FVIII treatment causes thrombin formation, which can induce immune responses

Based on the data provided, we reasoned that a possible mechanism linking FVIII treatment to the activation of the immune system is mediated downstream, through thrombin formation. Thrombin then provides costimulation for the induction of immune responses. We confirmed that FVIII treatment causes a detectable increase in thrombin generation (supplemental Table 1). To test the immunostimulatory activity initiated by FVIII, we administered FVIII along with another foreign antigen, OVA, which, as shown in Figure 1, was poorly immunogenic under standard conditions. If FVIII triggers thrombin generation to activate costimulatory pathways, then immunity to a foreign protein in the same microenvironment would be predicted. In this experiment, 3 groups of mice were treated with FVIII, OVA, or FVIII and OVA in the same bolus injection. When we assayed the immune response to FVIII, there was no difference between the groups that received FVIII and FVIII + OVA; this eliminated any concerns of antigenic competition under these conditions (Figure 6A-B). Interestingly, when we measured the anti-OVA response, we saw a significant increase comparing the OVA + FVIII group to the group treated with OVA alone (Figure 6C-D). These data further support the assertion that through FVIII's function in the coagulation cascade to generate thrombin, nonspecific costimulatory signals are produced for antigens not physically linked to FVIII.

FVIII activates factors that provide nonspecific costimulation. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 weekly injections of 1 μg FVIII intraperitoneally (n = 6) or 1 μg OVA intraperitoneally (n = 6) or 1 μg OVA + 1 μg FVIII (n = 6). This experiment has been repeated twice, and representative results are reported here. (A) Average concentrations of anti-FVIII antibodies in mice treated with FVIII only (270 ± 76 μg/mL) are not significantly different from mice treated with OVA + FVIII (293 ± 98 μg/mL). Values from mice treated with OVA represent the background for this assay and have been subtracted. (B) T-cell proliferation in response to FVIII has been measured for all 3 treatment groups. Again, there is no difference between FVIII and OVA + FVIII, in terms of response to FVIII. (C) Serum samples have been assayed for antibodies specific for OVA. When mice are treated with OVA + FVIII, they form measurable antibody responses to OVA (30.2 ± 7 μg/mL) that are significantly increased over those treated with only OVA (5.8 ± 2 μg/mL). Background values from mice treated with FVIII have been subtracted (**P = .004). (D) In addition, mice treated with OVA + FVIII have a measured T-cell response to OVA, whereas the other groups do not (**P = .009).

FVIII activates factors that provide nonspecific costimulation. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 weekly injections of 1 μg FVIII intraperitoneally (n = 6) or 1 μg OVA intraperitoneally (n = 6) or 1 μg OVA + 1 μg FVIII (n = 6). This experiment has been repeated twice, and representative results are reported here. (A) Average concentrations of anti-FVIII antibodies in mice treated with FVIII only (270 ± 76 μg/mL) are not significantly different from mice treated with OVA + FVIII (293 ± 98 μg/mL). Values from mice treated with OVA represent the background for this assay and have been subtracted. (B) T-cell proliferation in response to FVIII has been measured for all 3 treatment groups. Again, there is no difference between FVIII and OVA + FVIII, in terms of response to FVIII. (C) Serum samples have been assayed for antibodies specific for OVA. When mice are treated with OVA + FVIII, they form measurable antibody responses to OVA (30.2 ± 7 μg/mL) that are significantly increased over those treated with only OVA (5.8 ± 2 μg/mL). Background values from mice treated with FVIII have been subtracted (**P = .004). (D) In addition, mice treated with OVA + FVIII have a measured T-cell response to OVA, whereas the other groups do not (**P = .009).

Thrombin is sufficient to initiate and amplify immune responses

FVIII treatments can trigger thrombin generation, which can provide costimulation for immune responses. Because those with hemophilia A do not form complete FVIII, this therapeutic protein would be considered a “foreign” antigen by their immune systems. To uncouple the immune response seen in patients from the disease itself, we directly administered thrombin to hemostatically normal BALB/c mice with an unrelated, foreign antigen. This would allow us to determine whether thrombin augments the immune response to “foreign” antigens. In preliminary experiments (data not shown), mice were injected with 3 concentrations of thrombin (0.5, 5, and 50 IU) and a single concentration of OVA (1 μg) intraperitoneally to test for the potential side effects of thrombin; none of these thrombin doses was lethal. There was a dose-dependent increase in antibody production correlating with increased thrombin. An intermediate dose of thrombin was selected and 2 groups of naive mice were treated with OVA or OVA + thrombin. As shown in Figure 7, addition of thrombin led to increased antibody and T-cell responses to OVA.

Thrombin is sufficient to initiate and amplify immune responses. Hemostatically normal BALB/c were immunized with either intraperitoneal OVA (1 μg; n = 7) or intraperitoneal OVA (1 μg) + thrombin (5 IU; n = 8). Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response to OVA (17.9 ± 5.1 [OVA] vs 169.5 ± 39.7 [OVA + thrombin] μg/mL; **P = .002). (B) Splenic T cells were assayed for the response to OVA. **P = .004. These data indicate that thrombin is sufficient to provide costimulation for the initiation of immune responses to “foreign” proteins.

Thrombin is sufficient to initiate and amplify immune responses. Hemostatically normal BALB/c were immunized with either intraperitoneal OVA (1 μg; n = 7) or intraperitoneal OVA (1 μg) + thrombin (5 IU; n = 8). Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response to OVA (17.9 ± 5.1 [OVA] vs 169.5 ± 39.7 [OVA + thrombin] μg/mL; **P = .002). (B) Splenic T cells were assayed for the response to OVA. **P = .004. These data indicate that thrombin is sufficient to provide costimulation for the initiation of immune responses to “foreign” proteins.

Discussion

Treatment of hemophilia A patients can have the unintended consequence of immunizing the patient to the cure. Many of the risk factors for inhibitor development and research on tolerance induction have been reviewed.4,5,40 Herein, we use a mouse model where the immune response is highly predictable and reproducible. These FVIII−/− mice have a targeted deletion in exon 16 and produce no detectable plasma FVIII; thus, it models as a severe hemophilia A mutation. In this report, we demonstrate that FVIII has a property that allows it to elicit an immune response in the absence of extrinsic adjuvant. We have identified this property as its ability to generate thrombin, which is paramount to its immunogenicity. OVA, a different “foreign” antigen, which does not generate thrombin, does not elicit the same type of response. Interestingly, administration of FVIII with OVA allows for an immune response to OVA. Importantly, when we injected thrombin with OVA, an immune response to OVA was elicited. These data uncouple the immunogenicity of FVIII in hemophilia A mice (and patients) from the conformational structure of the protein. Thus, we conclude that the immunogenicity of FVIII is linked to its function, namely, its ability to generate thrombin, and not to the underlying pathology of this disease. The evidence provided in this report supports the hypothesis that the thrombin produced after FVIII treatment is sufficient to provide costimulation for the initiation of immune responses to “foreign” proteins.

We initially tested the role of FVIII function by heating it to 56°C, which prevents its procoagulant activity. Heating destroyed some but not all B-cell epitopes (conformational domains) but did not alter any of the T-cell epitopes (primary sequence). We found that the immune response measured by both antibody production and T-cell proliferation was significantly reduced, suggesting that the heat-inactivated FVIII was less immunogenic because it was not functional. Notably, the inactivated FVIII still elicited a minor immune response to the inactivated protein. This could be explained by the induction of protein aggregates during the heating process that can increase immunogenicity.19-21 These aggregates could then be immunogenic through mechanisms not related to thrombin formation. It is also possible that because we have reduced the number of B-cell epitopes, we have also altered the ability of FVIII-specific B cells to function as APCs during a primary immune response. We think that this is unlikely based on the observation that dendritic cells are the most potent APC in a primary immune response.41,42 The data presented support the explanation that the functional activity of native FVIII serves to increase thrombin levels through the intrinsic pathway and amplify the immune response.

Experiments using the anticoagulants warfarin and hirudin, a direct thrombin inhibitor, serve to illustrate the importance of FVIII function in immunogenicity because native, unaltered FVIII was used in these studies. Warfarin depletes factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX, and X, and hirudin selectively binds to thrombin to inactive it. Clearly, by diminishing thrombin activity, we prevented the costimulation necessary to fully activate the immune system. A logical extension of our hypothesis could also be applied to understanding the immune response in patients with hemophilia B being treated with exogenous FIX. However, a lower percentage of patients with hemophilia B form inhibitors. This may be because patients with major deletions in FIX are rare; hence, the majority of patients possess more cross-reactive material that can induce tolerance.43 Nonetheless, it would be interesting to pursue what role thrombin plays in the formation of inhibitors in that system.

Although we have not yet determined the exact “danger signal” originating from this system, others have shown that thrombin has both hemostatic and immunologic functions. Thrombin is able to interact with the immune system by activating platelets,44 causing mast cell degranulation,45 triggering macrophages to secrete cytokines,46 increasing vascular permeability,47 and inducing neutrophil chemotaxis.48 In addition, thrombin has been shown to play a role in transplantation rejection.49

The mouse model used in these experiments is a useful tool for understanding the pathology and exploring treatments for hemophilia. Clearly, there is minimal therapeutic utility in coadministration of the procoagulant FVIII with anticoagulants to prevent immunity. However, isolating the substrate for thrombin's protease activity and the source that signals “danger” to the immune system is paramount for optimizing treatment of hemophilia A. The ideal treatment would correct bleeding episodes in a minimally invasive way without initiating inhibitor formation to life-saving FVIII treatments.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Diane Nelson for editorial advice when preparing this manuscript, Tatyana Pozharskaya and Galina Hayes for assistance collecting the data for the FVIII melting curve, Adam Frankel for assistance with statistical analysis, Dr Leonid Medved for his help related to the fluorescence study, and Drs Pete Lollar and Birgit Reipert for valuable reagents.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL061883-10, T32 HL007698-15) and the American Heart Association (predoctoral fellowship 0815219E).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: J.S. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; A.-H.Z. and Y.S. designed the research and analyzed data; and D.W.S. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: David W. Scott, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 800 West Baltimore St, Rm 319, Baltimore, MD 21201; e-mail: davscott@som.umaryland.edu.

![Figure 4. Warfarin prevents the initiation of an immune response to FVIII. FVIII−/−/BALB/c mice were pretreated with warfarin (n = 6) or PBS (n = 7) before the first and third of 5 intraperitoneal injections of 1 μg FVIII. This experiment was repeated twice, and representative data are shown. Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response (582 ± 232 [FVIII] vs 101 ± 24 μg/mL [FVIII + warfarin]; *P = .042) and (B) splenic T cells from the mice treated with FVIII or FVIII + warfarin were assayed for the response to FVIII (**P = .002). These data indicate that other coagulation factors besides FVIII are probably necessary for initiation of the immune response.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/21/10.1182_blood-2008-10-186452/4/m_zh89990944920004.jpeg?Expires=1769108731&Signature=y9n94Xa1RYNmu7H0if4VADxT1PKQq6sA7-RnHN2QhCecP6cdEcLulKopED7KUDm~0yypi8OZwR5FmBbjeC-oyguUBVCdUggecddFR6j6ntvV8twyOsjFlXa~oN8~I6lBpOSkMmHhec~7h6QFYVmnnaxTyWpHIlNelApz1-dZBCHy0IYklYOE-tw5l-pABgb1EHDsFjYckbA8uff-8625DqtrLRN53y5SNKcMCa7inU4oJOxxO9Lvv4WJi555KAU0M8kPDDPn4V2W75yUUV-2y9SiqBNWjPXbl~IPFyBcWZMS9cDHm3y~yFRzaxtbj1czOnxf2CeJRabNkS8G4O0k-A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Hirudin inactivates thrombin and reduces the immunogenicity of FVIII. FVIII−/−/C57BL/6 mice received 5 intraperitoneal injections of 1 μg FVIII (n = 5) only or 1 μg FVIII with 200 μg hirudin (n = 5). This experiment was repeated twice, and representative results are reported here. Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response (515 ± 168 [FVIII] vs 134 ± 16 [FVIII + hirudin] μg/mL; *P = .02) and (B) splenic T cells were assayed for the response to FVIII (*P < .002). These data indicate that thrombin is necessary for initiation of the immune response to FVIII.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/21/10.1182_blood-2008-10-186452/4/m_zh89990944920005.jpeg?Expires=1769108731&Signature=sOoFfj7IJBsawMuXSQ68WoxtcTcdqYTrJIRCltQPXnedZKHBK6eM0~CxVK9IXzEHNx5ri8UEEOS5owv-mSZvVEhmeMZHL~ZR3m8Hq6~sAtdNJUe76IvdyfS3XDgkGXwqbKIE3DpX9kcFwdfEiMYplLJ~VSWcTUs37F71Xx7s~lFWJhpSX16i86O9dMgexNXlK6Mx91uH3VAhLzwBEjU0KrErtBuqsLAC5JDzo~UOkPIxFM~b9IYCxdKniOYHsVpiFZ5o8tST~gjBPKHzNYBSXQA89wIR4r0aXssLTyDhXlwAiPyCxh5f5dO6UP8Xyx1DJQA9Rk-V-igBSC2Rs6bObQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. Thrombin is sufficient to initiate and amplify immune responses. Hemostatically normal BALB/c were immunized with either intraperitoneal OVA (1 μg; n = 7) or intraperitoneal OVA (1 μg) + thrombin (5 IU; n = 8). Seven days after the last injection, (A) serum samples were analyzed for antibody response to OVA (17.9 ± 5.1 [OVA] vs 169.5 ± 39.7 [OVA + thrombin] μg/mL; **P = .002). (B) Splenic T cells were assayed for the response to OVA. **P = .004. These data indicate that thrombin is sufficient to provide costimulation for the initiation of immune responses to “foreign” proteins.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/114/21/10.1182_blood-2008-10-186452/4/m_zh89990944920007.jpeg?Expires=1769108731&Signature=V~THTbKajsPNRpV9-sMX4UR4ovu5F2mDV4TOnwjOI8BKcfbrzUAeLCfrmz7JjpsI7beYzqdjfFuhvhk106MHlXrnvhXmqsaISxkXfikRq4EWV43~K9HKeMTOSE1w2mLj4kZIW5LiEX6hTzouJrJawhdZU4gvQ5GHXZCJo3NCV4xofU1uaJITXeubbzUr2p7k8HiF9f21oEPyei4MwMdf3ThwFyv7o09dTlPnk6PnOA6~tdgkXD~pvSukwtAlYjHJ3W3SkNV0YPxP1DTXyUVGeUR5BVLgRFGI~LPad~j850X8JkbQ1C89IFT3VzLVegMYn2TclPczukWC-x3WnwvH0g__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)