Abstract

The general notion that functional platelets are important for successful hematogenous tumor metastasis has been inaugurated more than 4 decades ago and has since been corroborated in numerous experimental settings. Thorough preclinical investigations have, at least in part, clarified some specifics regarding the involvement of platelet adhesion receptors, such as thrombin receptors or integrins, in the metastasis cascade. Pivotal preclinical experiments have demonstrated that hematogenous tumor spread was dramatically diminished when platelets were depleted from the circulation or when functions of platelet surface receptors were inhibited pharmacologically or genetically. Such insight has inspired researchers to devise novel antitumoral therapies based on targeting platelet receptors. However, several mechanistic aspects underlying the impact of platelet receptors on tumor metastasis are not fully understood, and agents directed against platelet receptors have not yet found their way into the clinic. In addition, recent results suggesting that targeted inhibition of certain platelet surface receptors may even result in enhanced experimental tumor metastasis have demonstrated vividly that the role of platelets in tumor metastasis is more complex than has been anticipated previously. This review gives a comprehensive overview on the most important platelet receptors and their putative involvement in hematogenous metastasis of malignant tumors.

Introduction

Metastasis is the main cause of cancer-related death and a major challenge in today's cancer management. Although many new therapies against malignant tumors have been developed over the last years, the prognosis of most malignancies remains unfavorable, once metastatic spread has occurred. This challenge underlines the importance of understanding the details of metastasis to develop specific therapies to impede tumor dissemination.

The highly complex process of hematogenous tumor cell spreading includes detachment of cancer cells from the primary site, migration into and transport along the bloodstream, and, finally, tumor cell arrest and proliferation within the distant tissue. Thus, survival of the tumor cells within the bloodstream and adhesion in the vasculature at the metastatic sites are crucial for tumor cell dissemination. There is a plethora of studies indicating that the interaction of tumor cells with platelets within the bloodstream is essential during this early phase of metastasis and that agents directed against specific platelet receptors involved in this process may give rise to new therapies for patients with a high risk of metastasis or for minimizing the risk of cancer cell dissemination during antitumor surgery.

Platelets in hematogenous metastasis

The involvement of platelets and coagulation factors in hematogenous tumor metastasis has long been recognized. A relationship between venous thromboembolism and cancer has been observed at least since 1865,1 and more recent studies have shown that the risk of a diagnosis of cancer is clearly elevated after primary deep venous thromboembolism or pulmonary embolism.2 As a more direct evidence of platelet involvement in the development of malignant tumors, a relationship between elevated platelet count and malignant tumors was reported by Reiss et al in 1872.3 So far, thrombocytosis or even platelet counts that are within the upper normal range have been shown to be associated with advanced, often metastatic, stages of cancer and to be a negative prognostic marker for many different tumor entities, including endometrial carcinoma,4,5 cervical cancer,6 ovarian cancer,7 gastric cancer,8 or esophageal cancer.9

Clearly, it is difficult to differentiate whether elevated platelet levels actually constitute a predisposition toward a more aggressive disease per se. To our knowledge, there are no prospective studies evaluating the possible development of cancer and aggressive metastatic disease in initially healthy people with elevated platelet levels compared with people with low platelet counts. Although animal models certainly show a role for platelets in cancer metastasis, in patients it is harder to distinguish between a mere correlation between thrombocytosis and cancer and an actual causality. It seems most probable that thrombocytosis is, on the one hand, an unspecific paraneoplastic phenomenon triggered by the release of certain growth factors from the tumor,10 and by the general alteration the cancer causes in the metabolism of the host. On the other hand, elevated platelet counts generated in this way could then facilitate the growth and metastasis of the cancer.

Many experimental studies using in vitro models as well as in vivo models of metastasis in mice have given ample evidence for a mechanistic link between tumor cell spreading and platelet activation. In most of these in vivo studies dealing with hematogenous metastasis and platelets, the “experimental” model of metastasis has been used in which large numbers of tumor cells are injected intravenously into mice. This somewhat artificial model mimics the process of hematogenous metastasis in a simplified way as metastasis is more probable to be a continuous or intermittent process instead of a singular event. Furthermore, in patients, such large numbers of tumor cells as are used in the experimental metastasis assays can only be expected to be released into the bloodstream at very late stages of the disease.11 Early stages of the disease, in which antimetastasis therapy would be more useful, are therefore poorly reflected by this model. However, compared with orthotopic tumor models and “spontaneous” metastasis, only experimental metastasis models offer the possibility to study the interactions between the tumor cells and the blood cells within a well-determined time frame. Control of the exact time point of metastasis also makes it possible to test which step of metastasis a certain inhibitor would intercept. Especially when testing new antibodies, it would often be difficult, if not impossible, to apply these proteins for several weeks while waiting for metastatic events to occur without causing an anaphylactic reactions in the mice. Finally, the injection of larger numbers of tumor cells has several practical advantages as it makes the detection of tumor metastases and the evaluation of subtle changes in the number of tumor cell colonies easier. Therefore, experimental metastasis models yield valuable information despite their obvious limitations.

As early as in 1968, it was shown that tumor cells can aggregate platelets in vitro (a process termed tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation [TCIPA]), and later it has been recognized that this aggregation correlates with the metastatic potential of cancer cells in vivo.12,13 Platelet depletion or even an inhibition of TCIPA reliably diminishes metastasis, seemingly without affecting the growth of established tumors, in different in vivo models of experimental pulmonary metastasis14-18 as well as in a murine model of spontaneous metastasis.17 Three-dimensional visualization of tumor cells arrested in the pulmonary vasculature of mice has shown the association of these cells with platelets as well as fibrinogen.19 It is thought that TCIPA is an indicator for several advantages of metastasizing cancer cells, most of which are only relevant during the early stages of metastasis, namely, from the time the tumor cell enters the bloodstream to the moment of successful extravasation of the tumor cell. Such advantages include the prolongation of tumor cell survival in the circulation, as a protective thrombus may shield tumor cells from recognition by the immune system. There is strong evidence to support the concept that platelets can limit the ability of natural killer (NK) cells to lyse tumor cells in vitro and in vivo, an observation that is reversed after NK-cell depletion.17,20 Very recent studies have shown that platelet-derived transforming growth factor-β, secreted on platelet activation by tumor cells, down-regulates the activating immunoreceptor NKG2D on NK cells.21 Second, arrest of tumor cells in the vasculature of a new extravasation site and interaction with endothelial cells may be promoted by interactions with platelets.22 Third, a number of growth factors supporting tumor growth and possibly angiogenesis, such as platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and angiopoetin-1, are released by platelets.23-25

Finally, to make matters yet more complex, recent findings have shown that platelets appear to be essential for regulating tumor vasculature hemostasis and for preventing intratumoral hemorrhage. This new effect is independent of the platelets' capacity to form thrombi and instead depends on their granule secretion.26,27

The process of TCIPA and, ultimately, of cancer metastasis appears to involve most known platelet receptors engaged in adhesion and aggregation of platelets. Experimental blockade of many of these platelet receptors has resulted in inhibition of TCIPA and diminished cancer cell metastasis, although several new publications have yielded partially contradictory results, implying that some proteins implicated in platelet adhesion may have roles in metastasis that go beyond promotion of tumor cell survival and adhesion.28 Nevertheless, platelet receptors present attractive targets for future therapeutic approaches to prevent metastasis in patients with high-risk cancer.

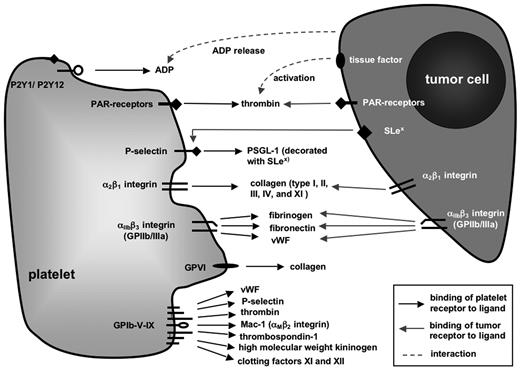

Targeting platelet receptors certainly poses a number of problems, such as the redundancy of prothrombotic pathways. In addition, there might be pleiotropic or even unforeseeable effects of pharmaceutics directed against receptors, which are also present on other cell types but platelets or are shed into the serum. Therefore, in search of such novel therapeutic approaches, understanding the role of each platelet receptor in the complex process of metastasis as well as under physiologic conditions is an absolute prerequisite. For this reason, this review gives a comprehensive overview over the most important platelet receptors and the experimental evidence linking them to metastasis before presenting some of the therapeutic advances, which have already been made in murine models or even in selected studies on human patients. Putative interactions of platelet surface receptors with tumor cells and/or metastasis-relevant ligands on other cells or extracellular compartments are shown in Figure 1.

Platelet receptors implicated in hematogenous tumor metastasis. Schematic representation of platelet surface molecules whose primary functions contribute to hemostasis and coagulation through binding to ligands expressed by other cells or extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules. Modulation of these molecules, for example, through platelet activation, in genetically engineered mice or by antibody-mediated blockade, has been shown in many cases to impact on experimental tumor metastasis.

Platelet receptors implicated in hematogenous tumor metastasis. Schematic representation of platelet surface molecules whose primary functions contribute to hemostasis and coagulation through binding to ligands expressed by other cells or extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules. Modulation of these molecules, for example, through platelet activation, in genetically engineered mice or by antibody-mediated blockade, has been shown in many cases to impact on experimental tumor metastasis.

Platelet receptors in TCIPA and metastasis

GPIb-IX-V

The glycoprotein Ib-IX-V-complex (GPIb-IX-V) along with GPVI are primarily responsible for initial platelet adhesion and activation in flowing blood by binding to their major ligands, von Willebrand factor (VWF) and collagen, respectively. GPIb-IX-V is a receptor complex constitutively expressed on the membrane of circulating platelets. Its components, the glycoproteins Ibα, Ibβ, IX, and V, all members of the leucine-rich repeat familiy, are displayed at a 2:2:2:1 ratio. The N-terminal extracellular part of GPIbα contains the partially overlapping binding sites for most interaction partners of the complex, among them the aforementioned VWF, the leukocyte integrin αMβ2 (CD11b/CD18, Mac-1),29 P-selectin (CD62P),30 thrombin, high molecular weight kininogen, thrombospondin-1, and clotting factors XI and XII.31-33 Especially under conditions of high shear stress, typical of arteriolar blood flow, interactions between GPIbα and the A1 domain of VWF immobilized on collagen or on the surface of activated platelets are crucial for the initial tethering and rolling of platelets at the site of vascular injury. Engagement of GPIbα is required for downstream activation of the integrin receptor αIIbβ3 and is thus an important initial step in the cascade that can finally lead to firm thrombus formation.

Although the putative involvement of GPIbα in tumor metastasis has been a subject of interest to many groups, it remains unclear which mechanisms of tumor cell spreading GPIbα might actually modulate. Some tumor cell lines, such as MCF7 cells, derived from a human breast cancer, may express GPIbα themselves, and antibody-mediated inhibition of this protein by whole divalent antibodies leads to diminished tumor cell-platelet interactions.34,35

However, GPIbα expressing tumor cell lines are an exception and, in most model systems, used to investigate tumor cell metastasis as well as TCIPA, GPIbα is exclusively expressed on megakaryocytes and platelets.36 In vitro assays to test GPIbα influence on tumor cell-platelet interactions have shown some very contradictory results, depending on tumor cell line and experimental setting. Whereas some groups have not perceived diminished interactions on blockade of GPIbα,12 early experiments performed by other groups do suggest a role of GPIbα in at least some phases of TCIPA.37,38

Similarly controversial results have been obtained when GPIbα functions in experimental metastasis were studied in vivo. Whereas reduced experimental pulmonary metastasis was observed in mice lacking GPIbα,39 functional inhibition of GPIbα by monovalent, monoclonal antibodies led to a strong increase in pulmonary melanoma metastasis in vivo16 (Figure 2). This apparent discrepancy might be explained by the fact that genetic deletion of GPIbα in mice leads to a severe bleeding phenotype with giant platelets that represents the human Bernard-Soulier syndrome.40 In addition, general changes in GPIbα expression might cause aberrant membrane development during megakaryocyte maturation.41,42 In contrast, monovalent antibody Fab fragments do not affect platelet counts and development.36

Examples for modulation of pulmonary melanoma metastasis through targeted interference with platelet receptors. In all experiments (performed by L.E. in the laboratory of M.P.S.), C57/BL6 mice were intravenously injected with 2.5 × 105 B16F10 melanoma cells, and pulmonary metastasis was evaluated after 10 to 14 days. (A) Antibody-mediated depletion of platelets prevents metastasis formation. (B) Inhibition of platelet GPIbα by function-blocking, monovalent Fab fragments results in a marked increase of pulmonary melanoma metastases. (C) Inhibition of GPIIb/IIIa by specific Fab fragments decreases the number of metastatic melanoma nodules in the lung. (D) Antibody-mediated blockade of GPVI does not significantly influence pulmonary melanoma metastasis. (E) P-selectin deficiency causes marked reduction of pulmonary melanoma metastasis.

Examples for modulation of pulmonary melanoma metastasis through targeted interference with platelet receptors. In all experiments (performed by L.E. in the laboratory of M.P.S.), C57/BL6 mice were intravenously injected with 2.5 × 105 B16F10 melanoma cells, and pulmonary metastasis was evaluated after 10 to 14 days. (A) Antibody-mediated depletion of platelets prevents metastasis formation. (B) Inhibition of platelet GPIbα by function-blocking, monovalent Fab fragments results in a marked increase of pulmonary melanoma metastases. (C) Inhibition of GPIIb/IIIa by specific Fab fragments decreases the number of metastatic melanoma nodules in the lung. (D) Antibody-mediated blockade of GPVI does not significantly influence pulmonary melanoma metastasis. (E) P-selectin deficiency causes marked reduction of pulmonary melanoma metastasis.

Even though the mechanism through which GPIbα influences metastasis remains to be investigated, there are several conceivable models to explain why monovalent antibody-mediated inhibition of GPIbα could enhance metastasis, an observation in apparent contrast to most publications dealing with platelets and metastasis. Interestingly, the metastasis-supporting effect of antibody-mediated GPIbα-inhibition is abolished in P-selectin–deficient mice,16 and it has been shown that tumor cells interact with the endothelium in a P-selectin–dependent manner.43 Therefore, it is conceivable that blockade of platelet GPIbα could result in an increased availability of P-selectin for tumor cell-endothelial interactions, thus supporting the attachment of tumor cells in the lung vasculature. An alternative hypothesis to explain the described effect on GPIbα-blockade results from the observation that VWF-knockout mice present a very similar phenotype in experimental tumor metastasis.44 With VWF being the major ligand of GPIbα, it is tempting to assume that the abolishment of this interaction, which occurs mainly under conditions of high mechanical shear, could lead to an arrest of the tumor cells in regions where mechanical conditions are better suited for tumor cell survival. However, whether there is any mechanistic connection between GPIbα and VWF in terms of tumor cell metastasis remains to be elucidated.

Thus, although platelet GPIbα remains an interesting molecule for further studies in the context of metastasis, the advantages of its blockade as an antimetastatic treatment must be questioned very carefully.45

GPVI

GPVI is a receptor of the immunoglobulin superfamily and the major platelet collagen receptor to mediate cellular activation. Signaling through GPVI leads to strong integrin activation and release of stored mediators, making GPVI essential for thrombus growth, even if it is, similar to GPIb-IX-V, also unable to mediate firm adhesion by itself. Of note, although GPVI is a central molecule for normal platelet function, no involvement in metastasis has hitherto been shown46,47 (Figure 2).

Integrins

Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors composed of a larger α- and a smaller β-subunit, which are noncovalently linked to each other. On inactivated (“resting”) platelets, integrins are presented in a low affinity state. Platelet activation leading to “inside-out” signaling results in conformational changes that enable high-affinity interactions with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and with other cells. “Outside-in” signaling through ligand-receptor interactions with activated integrins can then lead to subsequent reinforcement of platelet interactions with the ECM.48,49 The 2 integrins considered to be most important for platelet adhesion and aggregation are integrins α2β1 and αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa).

Integrin α2β1.

On activation, in which GPVI appears to play a crucial role, this collagen receptor binds to collagen types I, II, III, IV, and XI. Although the activation-associated conformational change is thought to be a prerequisite for signaling through α2β1, the integrin might be able to establish initial contacts to collagen, even in a low affinity state, before GPVI-induced activation.47,50,51

Although little is known about α2β1 in platelet-dependent cancer cell metastasis, the integrin receptor appears to play a role for the adhesion of certain cancer cell lines to the ECM, as some tumor cell lines express the receptor themselves and make use of its collagen-binding qualities to settle at metastatic sites. For example, pancreatic cancer cells adhere to type I collagen in vitro and are able to grow within the bone tissue in vivo if they express the integrin receptor.52

GPIIb/IIIa.

The active binding site of integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) is exposed on inside-out signaling after the engagement of GPVI, GPIb-IX-V, thrombin receptors (protease-activated receptor-1 [PAR-1] or PAR-4), or adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptors (P2Y(1) or P2Y(12)). This enables the integrin, which is absolutely crucial for platelet functioning, to bind several ligands containing an arginine-glycine-aspartic acid motif, such as fibrinogen, fibronectin, and VWF. Ligand binding by GPIIb/IIIa then leads to platelet aggregation, platelet spreading, clot retraction, and outside-in signaling events.53,54

Of all platelet receptors mentioned in this review, GPIIb/IIIa probably has the longest career as a metastasis-related molecule. As early as 1987, the role of GPIIb/IIIa in TCIPA was established,37,38 and a year later the importance of this integrin for tumor cell-platelet interactions was shown for several different tumor cell lines, among them 2 colon cancer cell lines as well as B16 melanoma cells (Figure 2) and T241 Lewis bladder cells.12 In the same publication, the in vivo importance of platelet GPIIb/IIIa in models of pulmonary metastasis was unveiled by blockade of GPIIb/IIIa before tumor cell injection with the monoclonal antibody 10E5.12 These findings have later been confirmed in numerous publications.16

Some more recent studies suggest a role of GPIIb/IIIa beyond the mediation of cancer cell-platelet interactions. Activation of platelet GPIIb/IIIa seems to be necessary for the release of angiogenic factors stored in platelet granules, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, a factor known to promote the angiogenic switch in tumor cell spreading, but also platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-β, and fibrinogen, all of which are secreted immediately after platelet activation.55-57

Considering the effective adhesion mechanism integrins provide for platelets and other cells, it is hardly surprising that many tumor cell lines themselves express the same integrins that are normally found on blood cells and platelets or on endothelial cells. These receptors add fundamentally to the malignancy of these tumor cells.55,58,59

Taken together, the crucial role αIIbβ3 plays in blood-borne metastasis makes this integrin receptor a very attractive target for antimetastatic treatments. Studies using an oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonist, XV454, in a mouse model of experimental metastasis has indeed yielded rather positive results concerning the inhibition of TCIPA and lung metastases formation.18 Of note, a number of agents directed against human αIIbβ3 have already been developed and approved to decrease the incidence of ischemic complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary artery intervention. These new compounds include abciximab (a Fab fragment of a chimeric human-mouse antibody), eptifibatide (a cyclic heptapeptide), and tirofiban (a tyrosine-derived nonpeptide molecule). It is conceivable that these or similar inhibitory drugs will gain further importance to protect patients in cancer stages that bear a high risk of metastatic dissemination.

ADP receptors

The adenine nucleotide ADP is a secondary mediator of platelet aggregation. It is released from platelet granules on activation through the aforementioned receptors, and it leads to the amplification of the initial hemostatic response. ADP acts through 2 G protein–coupled receptors, the Gq coupled P2Y(1) receptor and the Gi-coupled P2Y(12) receptor. Stimulation through these receptors leads to shape change, aggregation, and thromboxane A2 generation by platelets.60-62

Considering the importance of adenine nucleotide signaling, it is not surprising that ADP scavengers, such as apyrase, can almost completely inhibit TCIPA. Application of selective purinergic receptor antagonists against P2Y(1) or P2Y(12) seems to pinpoint P2Y(12) as the more important receptor in TCIPA.35 In cases where tumor cells able to induce TCIPA do not themselves produce ADP, inhibition of ADP-induced platelet stimulation aims at a secondary effect and does not hinder initial tumor cell interactions with platelets. However, several tumor cell lines possess the ability to generate ADP themselves; and in these cases, their potential for induction of TCIPA seems to be directly related to ADP production.63 In an approach to inhibit blood-borne metastasis of murine melanoma and breast carcinoma cells, respectively, it has been shown recently that combination of a soluble apyrase/ADPase, APT102, with acetylsalicylic acid can lead to a significant reduction of skeletal metastatic tumor burden in mice. Again, this indicates that inhibition of platelet aggregation in cancer may yet hold therapeutic options in the future.64

P-selectin

The 3 members of the selectin family, P-selectin (CD62P), E-selectin (CD62E), and L-selectin (CD62L), belong to the C-type lectins, which recognize sialylated, fucosylated carbohydrates, specifically glycans containing a terminal sialyl Lewisx (SLex), in a calcium-dependent fashion. Generally, selectins mediate transient leukocyte or platelet contacts with vascular endothelial cells.65 P-selectin is expressed on activated endothelial cells and platelets, whereas its major ligand, PSGL-1, is expressed mainly on circulating leukocytes. P-selectin and PSGL-1 regulate the initial interactions between leukocytes and the blood vessel wall along with several other selectin-selectin-ligand interactions, as well as between activated platelets and leukocytes.66 Furthermore, P-selectin and PSGL-1 have been implicated in blood coagulation, as fibrin generation in vascular thrombi is impaired in P-selectin–deficient mice and recruitment of tissue factor into the growing thrombus through monocyte-derived microparticles depends on P-selectin-PSGL-1 interactions.67,68 On platelet activation, P-selectin becomes rapidly translocated from its intracellular storage vesicles to the platelet surface.

In several in vivo metastasis models, P-selectin deficiency or blockade of P-selectin function has a dramatic inhibitory effect on metastasis43 (Figure 2). P-selectin binds to a number of tumor cell lines via sialylated fucosylated glycans displayed on mucin and nonmucin structures,69,70 and it has been shown that the expression of sialylated, fucosylated glycans, such as sialyl Lewisx and sialyl Lewisa, correlates with a poor prognosis as far as metastatic spread of tumor cells is concerned.71,72

On inhibition of P-selectin or in P-selectin–deficient mice, platelets fail to adhere to tumor cells in vitro and in vivo,43,73 making it probable that interrupted tumor cell-platelet interactions in P-selectin deficiency account at least partially for the protective effect of P-selectin blockade. However, tumor cell dependency on P-selectin on platelets during metastasis is only part of the story, as several melanoma cell lines appear to interact with vascular endothelium in an endothelial P-selectin–dependent manner.43 Interestingly, heparin has been shown to effectively inhibit P-selectin, and already a single dose of heparin administered in models of experimental metastasis before the injection of tumor cells can effectively attenuate metastasis.74 This effect can be ascribed to heparin mimicking the natural ligand of P-selectin by display of a high density of carboxylic acid groups.75 The effect is not dependent on the anticoagulant qualities of heparin,74 a notion that may have direct therapeutic significance in anticancer therapy.

Thrombin receptors

Thrombin is the main effector protease of the coagulation cascade. It becomes activated after a series of zymogen conversions, when circulating coagulation factors come in contact with tissue factor. The latter becomes accessible on damage of the vascular wall.73 In platelets, thrombin provokes shape change and secretion, synthesis and release of thromboxane A2, enhanced expression of P-selectin and CD40 ligand on the platelet surface, and integrin activation. Furthermore, thrombin enhances exposure and activation of the integrin αIIbβ3 and induces the release of platelet fibronectin and VWF onto the platelet surface. This clearly makes thrombin one of the most potent activators of platelets.76-78

Thrombin signaling is mediated through a family of G protein–coupled PARs. PAR-1, as the prototype of this receptor family, becomes activated through cleavage of its N-terminus by thrombin. On cleavage, the new amino-terminal peptide will act as a tethered ligand that binds intramolecularly to the body of the receptor, thereby causing transmembrane signaling.79 Mammalian genomes contain 4 PARs: PAR-1 to PAR-4, with PAR-2 being activated by trypsin and not thrombin. In humans, PAR-1 and PAR-4 respond to thrombin, with PAR-1 being the more important receptor of the 2.80 In contrast, mouse platelets use PAR-3 and PAR-4, with PAR-3 functioning as a cofactor for thrombin signaling and PAR-4 being the major receptor in mice.81

Similarly to αIIbβ3, the importance of thrombin for metastasis in vitro and in vivo has been recognized for some time. Thrombin stimulation of platelets increases their adhesion to tumor cells. This activation also occurs when the tumor cells, not the platelets, are incubated with thrombin.82 The latter interesting effect might be explained, at least in part, by the observation that several tumor cell lines, including some melanoma cells, not only express tissue factor to activate thrombin, but also PAR receptors, a phenotype that appears to be associated with a higher metastatic potential.83-85 PAR-1 activation in tumor cells stimulates the expression of adhesion molecules, such as integrins αIIbβ3, αVβ5, or αVβ3.86-88 Thrombin-activated tumor cells not only interact with platelets in a stronger way than nonactivated cells but also show a greater capacity for adhering to endothelial cells in vitro.89-91

Knowing all this, it is not surprising to find that simultaneous injection of tumor cells with thrombin in a model of pulmonary metastasis strongly enhances the number of pulmonary metastases in mice. In line with this, PAR-4–deficient mice, whose platelets fail to respond to thrombin stimulation, show a marked reduction in experimental pulmonary metastasis when injected with melanoma cells.92 Finally, thrombin might act as a growth-stimulatory mediator through its activation of PAR receptors. In addition, it acts as an inducer of angiogenesis, thus further contributing to tumor growth and sustainment.25

Therapy

Even though many aspects of the interaction of platelet receptors and tumor cells still remain incompletely understood, there are some very promising approaches in this field that have shown efficacy in mouse models and, perhaps more importantly, in trials with patients who have malignancies.

The biggest progress has so far been made in the field of P-selectin inhibition by unfractionated heparin or certain low molecular weight heparins. Indeed, it has long been recognized that heparins may have beneficial effects when applied to patients with malignancies.93,94 Because such activities were thought to be an exclusive result of the anticoagulatory capacity of heparin, clinical trials were conducted with the more easily manageable and orally available anticoagulant drug warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, which, unfortunately, failed to show any clinical benefit for most types of cancer, except for small cell lung cancer.95,96 Rather than merely blocking coagulation, heparins can inhibit the interaction of P-selectin with its natural ligands as heparins possess characteristics similar to natural P-selectin ligands.75 Therefore, a single dose of unfractionated heparin can, at least in murine models of experimental metastasis, effectively attenuate metastasis, a phenomenon that is not dependent on the anticoagulatory qualities of heparin and that is abated in mice lacking P-seletin.43,69,74 Apart from that, heparin has a complex influence on the behavior of malignant cells, which includes the inhibition of heparanases produced by malignant cells, which mediate invasiveness, metastasis, and angiogenesis.97 Whether these characteristics are clinically important in anticancer therapy, especially compared with the well-defined anti–P-selectin activities, remains to be discussed.

Given that unfractionated heparins have a greater risk of causing adverse effects, such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and as they have a poor bioavailability, many low molecular weight heparins, such as tinzaparin, nadroparin, dalteparin, or enoxaparin, have been created by different methods of heparin degradation and are preferentially used in clinical practice. When taking into account a possible application of these low molecular weight heparins in cancer patients, it must be considered that in vitro and in murine experimental metastasis models these drugs have very different capacities for inhibiting P-selectin binding and for attenuation of metastasis. Of the aforementioned pharmaceutics, tinzaparin and nadroparin appear to be potent inhibitors of P-selectin functions. For tinzaparin, this can be explained by the fact that tinzaparin contains more high molecular weight heparin fragments than the other species.98 For nadroparin, the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated.99 Whereas all low molecular weight heparins may be expected to prevent venous thromboembolism associated with malignancy, their putative antimetastatic effect can vary greatly. Of note, fondaparinux, a synthetic heparinoid pentasaccharide that specifically binds to antithrombin, showed no ability to inhibit P-selectin at all.98 This is reflected in metastasis studies in murine models where fondaparinux completely failed to inhibit tumor metastasis.98

As summarized in Table 1, certain promising effects on metastasis have not only been observed in murine models but also in a limited number of clinical studies in patients with malignancies. A summary of larger clinical studies evaluating these effects of anticoagulant treatment with heparinoids is given in Table 1. Importantly, most of these studies showed that treatment with a heparin derivative could only yield a positive effect on the survival of patients when the patients did not have manifest metastatic disease at the time of treatment initiation. This is directly in line with the aforementioned preclinical observations that heparins mainly interfere with the establishment of metastases rather than with the growth of tumor cell colonies. Interestingly, many studies have shown a prolonged beneficial effect, which goes beyond the time of heparin administration, which may again indicate a modification of tumor biology.

Synopsis of randomized studies evaluating the treatment of cancer patients with low molecular weight heparins

| Study . | Study design . | No. of patients . | Study type . | Tumor entity . | Duration . | Result . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al (CLOT; 2005)100 | Dalteparin subcutaneously anti-Xa 200 IU/kg once daily for 1 month, then 150 IU/kg for 5 months versus dalteparin 200 IU/kg for1 week followed by a VKA | 676 | Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled | Solid tumors (colorectal, breast, lung, gynecologic, genitourinary, brain, pancreas) in patients with VTE | 6 months | No difference in survival at 12 months for the entire population; in the subgroup of patients without metastatic disease, the probability of death at 12 months was 20% in the dalteparin group versus 36% in the VKA group (P = .03) |

| Altinbas et al (2004)101 | Chemotherapy alone versus dalteparin 5000 IU subcutaneously once daily and chemotherapy | 84 | Randomized, prospective | Small cell lung cancer | 18 weeks | Increase of median survival from 8 to 13 months (chemotherapy vs dalteparin plus chemotherapy, respectively; P = .01) |

| Kakkar et al (FAMOUS; 2004)102 | Placebo or dalteparin, 5000 IU subcutaneously per day | 385 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Advanced cancer breast, colorectal, ovarian, pancreatic, liver, genitourinary, uterus | 1 year | No significant benefit on overall survival at 1, 2, and 3 years after therapy; significant increase in survival after 2 years (78% vs 55%) and 3 years (60% vs 36%) in a subgroup with better prognosis (survival > 17 months; P = .03) |

| Klerk et al (MALT; 2005)103 | Nadroparin, adapted to body weight or placebo; administration twice daily for 14 days and once daily for another 4 weeks | 302 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Advanced cancer: lung, breast, colorectal, gastric or esophageal, melanoma, ovarian, pancreatic, liver, genitourinary, uterus, prostate, renal | 6 weeks | Increase of median survival from 6.6 to 8 months in the nadroparin group versus placebo, respectively (P = .021); in the patient group with an estimated life expectancy ≥ 6 months, median survival increased from 9.4 to 15.4 months (P = .01) |

| Sideras et al (2006)104 | Standard therapy with placebo or in combination with 5000 IU dalteparin subcutaneously per day | 138 | Phase 3, originally randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, later changed to open-label | Advanced cancer: breast, colon, lung, or prostate | Life-long | No survival benefit for LMWH in patients with advanced cancer |

| Griffiths et al (FRAGMATIC; 2009)105 | Standard therapy alone or standard therapy plus dalteparin, 5000 IU subcutaneously per day | 2200 | Phase 3 clinical study, randomized, controlled, open-label | Small cell or nonsmall cell bronchial carcinoma | 24 weeks | Presently running study |

| Study . | Study design . | No. of patients . | Study type . | Tumor entity . | Duration . | Result . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al (CLOT; 2005)100 | Dalteparin subcutaneously anti-Xa 200 IU/kg once daily for 1 month, then 150 IU/kg for 5 months versus dalteparin 200 IU/kg for1 week followed by a VKA | 676 | Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled | Solid tumors (colorectal, breast, lung, gynecologic, genitourinary, brain, pancreas) in patients with VTE | 6 months | No difference in survival at 12 months for the entire population; in the subgroup of patients without metastatic disease, the probability of death at 12 months was 20% in the dalteparin group versus 36% in the VKA group (P = .03) |

| Altinbas et al (2004)101 | Chemotherapy alone versus dalteparin 5000 IU subcutaneously once daily and chemotherapy | 84 | Randomized, prospective | Small cell lung cancer | 18 weeks | Increase of median survival from 8 to 13 months (chemotherapy vs dalteparin plus chemotherapy, respectively; P = .01) |

| Kakkar et al (FAMOUS; 2004)102 | Placebo or dalteparin, 5000 IU subcutaneously per day | 385 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Advanced cancer breast, colorectal, ovarian, pancreatic, liver, genitourinary, uterus | 1 year | No significant benefit on overall survival at 1, 2, and 3 years after therapy; significant increase in survival after 2 years (78% vs 55%) and 3 years (60% vs 36%) in a subgroup with better prognosis (survival > 17 months; P = .03) |

| Klerk et al (MALT; 2005)103 | Nadroparin, adapted to body weight or placebo; administration twice daily for 14 days and once daily for another 4 weeks | 302 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Advanced cancer: lung, breast, colorectal, gastric or esophageal, melanoma, ovarian, pancreatic, liver, genitourinary, uterus, prostate, renal | 6 weeks | Increase of median survival from 6.6 to 8 months in the nadroparin group versus placebo, respectively (P = .021); in the patient group with an estimated life expectancy ≥ 6 months, median survival increased from 9.4 to 15.4 months (P = .01) |

| Sideras et al (2006)104 | Standard therapy with placebo or in combination with 5000 IU dalteparin subcutaneously per day | 138 | Phase 3, originally randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, later changed to open-label | Advanced cancer: breast, colon, lung, or prostate | Life-long | No survival benefit for LMWH in patients with advanced cancer |

| Griffiths et al (FRAGMATIC; 2009)105 | Standard therapy alone or standard therapy plus dalteparin, 5000 IU subcutaneously per day | 2200 | Phase 3 clinical study, randomized, controlled, open-label | Small cell or nonsmall cell bronchial carcinoma | 24 weeks | Presently running study |

VKA indicates vitamin K antagonist; VTE, venous thromboembolism; and LMWH, low molecular weight heparin.

Taken together, statistically significant improvements on overall survival of cancer patients have been reported on application of heparinoids, especially in patients with nonmetastatic disease. However, their true therapeutic value as an antimetastatic drug must be further tested in larger trials and with a better consideration of the different tumor entities as different solid tumors may respond very differently to anticoagulation. Therefore, the FRAGMATIC trial, which is currently being conducted,105 appears to be promising as it has the goal of including 2200 patients with primary bronchial carcinoma.

When talking about heparinoids in cancer treatment, it is also important to bear in mind that heparinoids may have pleiotropic effects on the establishment of metastases and the growth of tumor colonies. Therefore, a novel and questionably more elegant approach to inhibit disease progression in cancer patients would be a targeted therapy against selectins. This could be achieved by antibodies directed against P-selectin, such as the antibody RB40.34, which has so far been used in murine models of cerebral ischemia and restenosis.106 Recombinant selectin counter-receptors, antibodies directed against the natural selectin counter-receptors as well as low molecular weight antagonists, also represent interesting concepts to prevent metastasis, even though none of these substances is, to our knowledge, at present being tested in clinical trials in the context of cancer.

Similarly attractive and clinically much better studied are substances directed against the integrin αIIbβ3. Such therapeutics could include the aforementioned αIIbβ3-antagonists abciximab, eptifibatide, and tirofiban which have already been approved for preventing ischemic complications in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary artery intervention. Although these substances have, to our knowledge, not yet been tested in the context of metastasis, the oral GPIIb/IIIa antagonist XV454 has been shown to attenuate lung metastasis in a murine model of experimental metastasis.18 It might therefore be interesting to pursue this approach.

Antibodies directed against integrins appear to be another promising option. For example, a recent study in rats has shown an antiangiogenic and growth-inhibiting effect of the m763 antibody, directed against αvβ3 and αIIbβ3 integrins.57 However, it is unclear whether platelets are involved in this activity as tumor growth and angiogenesis are rather late events in the metastatic cascade; and, importantly, no difference in the establishment of pulmonary metastases was seen under treatment with the integrin antagonist.57

Outlook

In conclusion, it has become clear that the coagulation system and, more specifically, platelet receptors involved in hemostasis influence tumor metastasis in many (and not always predictable) ways. In case of αIIbβ3 and thrombin receptors (PARs), the importance of these molecules for hematogenous metastasis (Table 2) has long been recognized, and the molecular mechanisms by which these effects are exerted are understood in principle. For other mediators of hemostasis, such as ADP or the GPIb-IV-X complex, the exact mechanisms underlying their involvement in metastasis remain to be further elucidated, even if some participation in cancer cell dissemination seems to be undeniable. Unfortunately, although research has been invested into platelet-tumor cell interactions over the last decades, this knowledge has not yet led to any breakthrough in cancer therapy. Indeed, so far no standardized protocol exists for platelet receptor-directed therapies in cancer disease, even though some smaller studies on very limited patient groups have yielded fairly optimistic results.76

Synopsis of platelet surface receptors and their putative roles in hematogenous tumor metastasis

| Platelet receptor . | Proposed implication in metastasis . |

|---|---|

| GPIb-IX-V | Questionable importance for TCIPA, mechanism unclear |

| GPIbα knockout mice show reduced metastasis | |

| Blockade of GPIbα with monovalent, monoclonal antibodies (Fab fragments) leads to enhanced metastasis | |

| GPVI | Hitherto, no association to metastasis or TCIPA |

| Integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) | Mediation of TCIPA |

| Platelet αIIbβ3 essential for pulmonary metastasis in various mouse models and a variety of cancer cell lines | |

| Aberrant expression on various tumor cell lines, enhancing their malignant potential | |

| Regulation of the release of angiogenic factors (vascular endothelial growth factor) from platelet granules upon tumor cell-induced platelet activation | |

| Integrin α2β1 (VLA-2) | Expressed by some tumor cells to facilitate binding to the ECM |

| ADP receptors | Release of ADP from platelet granules upon platelet activation, leading to secondary enhancement of TCIPA |

| Capability of some tumor cells to produce and release ADP themselves | |

| P-selectin | Binding of sialylated fucosylated glycans on mucin and nonmucin structures on cancer cell lines |

| Mediation of cancer cell interactions with activated platelets | |

| Enabling of tumor cell rolling on endothelial cells through endothelial P-selectin | |

| Thrombin receptors (PARs) | Enhancement of tumor cell-platelet interactions by activation of platelet or tumor cell PARs |

| Enhancement of tumor cell-endothelial cell interactions through thrombin | |

| Stimulation of integrin signaling in tumor cells | |

| Increase of metastatic foci in vivo through thrombin application, reduction of metastasis in PAR-4–deficient mice |

| Platelet receptor . | Proposed implication in metastasis . |

|---|---|

| GPIb-IX-V | Questionable importance for TCIPA, mechanism unclear |

| GPIbα knockout mice show reduced metastasis | |

| Blockade of GPIbα with monovalent, monoclonal antibodies (Fab fragments) leads to enhanced metastasis | |

| GPVI | Hitherto, no association to metastasis or TCIPA |

| Integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) | Mediation of TCIPA |

| Platelet αIIbβ3 essential for pulmonary metastasis in various mouse models and a variety of cancer cell lines | |

| Aberrant expression on various tumor cell lines, enhancing their malignant potential | |

| Regulation of the release of angiogenic factors (vascular endothelial growth factor) from platelet granules upon tumor cell-induced platelet activation | |

| Integrin α2β1 (VLA-2) | Expressed by some tumor cells to facilitate binding to the ECM |

| ADP receptors | Release of ADP from platelet granules upon platelet activation, leading to secondary enhancement of TCIPA |

| Capability of some tumor cells to produce and release ADP themselves | |

| P-selectin | Binding of sialylated fucosylated glycans on mucin and nonmucin structures on cancer cell lines |

| Mediation of cancer cell interactions with activated platelets | |

| Enabling of tumor cell rolling on endothelial cells through endothelial P-selectin | |

| Thrombin receptors (PARs) | Enhancement of tumor cell-platelet interactions by activation of platelet or tumor cell PARs |

| Enhancement of tumor cell-endothelial cell interactions through thrombin | |

| Stimulation of integrin signaling in tumor cells | |

| Increase of metastatic foci in vivo through thrombin application, reduction of metastasis in PAR-4–deficient mice |

TCIPA indicates tumor cell-induced platelet aggregation; ECM, extracellular matrix; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; and PARs, protease-activated receptors.

So what are some of the central challenges that need to be tackled for successful antitumoral therapies through modulation of platelet receptor functions? (1) As blocking of a given platelet receptor may be compensated for by other receptors, targeted therapies will have to overcome redundancy of platelet receptor functions. (2) Given that tumor cells may bear individual sets of potential ligands for platelet receptors, the functional repertoires of ligands of tumor cells will have to be analyzed individually. (3) Interactions of tumor cells with soluble platelet-secreted mediators, such as VWF, may be unpredictable. (4) Potential side effects of platelet receptor-directed compounds on vital mechanisms, coagulation in particular, will have to be evaluated carefully. (5) Some platelet receptors, such as P-selectin, may be expressed on other cell types, thus interfering with targeted therapies.

Hopefully, the mechanisms underlying the interactions of platelet surface receptors with tumor cells will become even better understood in the future, thus providing individual patients in high-risk situations for cancer cell spreading with a therapy to prevent this fatal development.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bernhard Nieswandt (Rudolf Virchow Center, DFG Research Center for Experimental Biomedicine, University of Würzburg) for the contribution of purified antibodies directed against some platelet epitopes and Richard O. Hynes (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA) for P-selectin–deficient mice.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe and the Wilhelm-Sander-Stiftung (M.P.S.).

Authorship

Contribution: L.E. and M.P.S. reviewed the literature and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Michael P. Schön, Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Georg August University, Von-Siebold-Strasse 3, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; e-mail: michael.schoen@med.uni-goettingen.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal