Abstract

Coagulation factors VII (FVII), IX (FIX), X (FX), and protein C share the same domain organization but display very different plasma half-lives. It is plausible that the half-life is influenced by the activation peptide, differing in length and glycosylation and missing in FVII. To test this hypothesis, the influence of activation peptides on the plasma half-life of human FVII was studied by administering human FVII variants containing activation peptide motifs to mice. Insertion of the activation peptide from FX gave 4-fold longer terminal half-life (5.5 hours vs 1.4 hours for FVII), whereas the activation peptide from FIX and protein C resulted in half-lives of 4.3 and 1.7 hours, respectively. Using FX's activation peptide we identified the N-linked glycans as structural features important for the half-life. The peptide location within the FVII molecule appeared not to be critical because similar prolongation was obtained with the activation peptide inserted immediately before the normal site of activation and at the C-terminus. However, only the latter variant was activatable, yielding full amidolytic activity and reduced proteolytic activity with preserved long half-life. Our data support that activation peptides function as plasma retention signals and constitute a new manner to extend the half-life of FVII(a).

Introduction

The vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors constitute a small family of plasma proteins with functions within the blood clotting cascade and its regulation. Four of them, factors VII (FVII), IX (FIX), X (FX), and protein C, share the same domain organization and can be converted to active enzymes by endoproteolytic cleavage. However, they differ when it comes to the presence of an activation peptide and, if present, its length, primary structure, and extent of glycosylation.1 The activation peptide, which is removed on activation of the zymogen to an enzyme, can be as long as 52 amino acid residues (in FX) but is absent in FVII. Because of an identical modular architecture and very similar sizes but dramatically different plasma half-lives of these 4 proteins, it is tempting to hypothesize that their duration in circulation somehow is dictated by their activation peptide. FVII has the shortest half-life, approximately 5 hours in humans,2,3 and recent studies with recombinant activated FVII (FVIIa) showed a similar half-life in adults.4,5 Thus, the half-life of FVIIa antigen appears to be similar to that of zymogen FVII, and this finding is in agreement with results obtained in studies in rats6,7 and mice.8 In addition, data from mice showed that the half-life of FVIIa antigen was not significantly affected by occupancy of the active site with a low-molecular weight inhibitor or by macromolecular inhibitor (antithrombin) complex formation.8 The half-life for the 3 related proteins, protein C, FIX, and FX, increases with increasing length of the activation peptide, being almost 2 days for FX in humans.9,10 In sharp contrast to the similar clearance kinetics of FVII and FVIIa, the activation of, for instance, FX to FXa results in a dramatic shortening of the half-life down to only a few minutes because of rapid neutralization by plasma inhibitors ensued by clearance of the FXa-inhibitor complexes.11,12

Because FVII completely lacks an activation peptide and has the shortest half-life within this protein family, the current study used zymogen FVII as the model scaffold to scrutinize the hypothesis that the activation peptide is largely responsible for the longer plasma half-lives of FIX, FX, and protein C. In this manner, information would be obtained about whether the prolongation of plasma duration is mediated by the activation peptide and whether the effect of the peptide can be induced outside the context of the parent protein. It would at the same time tell us whether the insertion of an activation peptide into FVII(a) could extend its half-life. If successful, this could have clinical implications because the therapeutic efficacy of FVIIa often requires multiple injections because of the limited functional half-life of the drug. Because it was indeed possible to increase the plasma half-life of FVII, the influence of the activation peptide location on the pharmacokinetics and FVII activation kinetics was also investigated. Furthermore, dissection of the FX activation peptide provided some insights into the structure-pharmacokinetics relationship. Altogether, our results suggest that an activation peptide motif functions as a plasma retention signal and that its introduction can be used as an alternative approach to those already proven to extend the half-life of FVIIa, namely, fusion to albumin,13 direct pegylation14,15 and formulation with pegylated liposomes.16 Although a sustained, prophylactic effect of recombinant FVIIa has been observed,17 the underlying mechanism is unknown and prolongation of the plasma half-life still offers a viable strategy for increased duration of action of FVIIa.

Methods

Reagents

FX and FXa were purchased from Enzyme Research Laboratories and the active site inhibitor Glu-Gly-Arg-chloromethylketone from Bachem. The chromogenic substrates S-2765 and S-2288 were from Chromogenix, and FIXa and FXIa from American Diagnostica. All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. The wild-type FVII expression plasmid pLN17418 was used as template for the cloning of the FVII mutants. The plasmids pKSLN123 (a gift from Dr Katrine S. Larsen, Novo Nordisk A/S) and pHOJ336 (a gift from Dr Henrik Østergaard, Novo Nordisk A/S) were used as templates for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of FX and FIX activation peptides, respectively. Recombinant wild-type FVIIa and soluble tissue factor (sTF) were prepared as described previously.19,20 TF1-244 (a gift from Dr Henrik Østergaard, Novo Nordisk A/S) was relipidated, with Triton X-100 as the detergent, according to Smith and Morrissey.21 Full-length lipidated TF (Innovin) was from Dade Behring.

Construction of FVII variants

FVII variants containing either the protein C (FVII_C), FIX (FVII_IX), or FX (FVII_X) activation peptide between Gly-151 and Ile-153, using Arg-152 in FVII as the terminal residue in the activation peptide, were constructed by overlap extension PCR. In a first PCR reaction, primer pair A and B was used to amplify the FVII light chain; primers C and D, the activation peptide to be inserted; and primers E and F, to amplify the FVII heavy chain. The protein C activation peptide, with only 12 amino acids, was possible to include in primers B_C and E_C, excluding the need to amplify that fragment. The sequences of all primers and the FVII variants used in this study are found in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The PCR reaction, using Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche Applied Science), was performed accordingly: after a 4-minute heating step at 94°C, 30 cycles of 94°C 15 seconds, 55°C 30 seconds, and 72°C 2 minutes followed by an extension time of 7 minutes at 72°C. The purified PCR products AB and CD were used as templates in a second PCR reaction, carried out as the first, with primer pair A and D to amplify FVII light chain and insert. Subsequently, the ABCD and EF products were used as templates with primer pair A and F in a third PCR, where the annealing temperature was raised from 55°C to 65°C, producing the complete product. All 3 constructs were digested with NheI and NotI restriction enzymes and ligated into a pCI-neo vector (Promega).

Sequences of PCR primers

| Primer . | Sequence (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|

| A | tcactataggctagcatggtctcc |

| B_C | cttggtcttcttggtcttctgtgtcgccttggggtttgctg |

| E_C | accaagaagaccaagtagatccgcgaattgtggggggca |

| B_IX | aaacagtctcagcgccttggggtt |

| C_IX | aaccccaaggcgctgagactgttt |

| D_IX | ccccacaattcgagtgaagtcat |

| E_IX | atgacttcactcgaattgtgggg |

| B_X | tgggccactgagccttggggttt |

| C_X | aaaccccaaggctcagtggccca |

| D_X | ccccacaattcgggtgaggttgtt |

| E_X | aacaacctcacccgaattgtgggg |

| D_X1-34 | ccacaattcggtcgaaggggttct |

| E_X1-34 | agaaccccttcgaccgaattgtgg |

| B_X30-52 | aaggggttctcgccttggggttt |

| C_X30-52 | aaaccccaaggcgagaacccctt |

| F | taaagggaagcggccgcctagggaaat |

| NNAAfwd | gcttgacttcgcccagacgcagcctgagaggggcgacaacgccctcacccg |

| NNAArev | cgggtgagggcgttgtcgcccctctcaggctgcgtctgggcgaagtcaagc |

| TTAAfwd | gacagcatcgcatggaagccatatgatgcagccgacctggaccccgccgagaacc |

| TTAArev | ggttctcggcggggtccaggtcggctgcatcatatggcttccatgcgatgctgtc |

| B_XHC | ctgggccactgagggaaatgg |

| C_XHC | ccatttccctcagtggcccag |

| D_XHC | taaagggaagcggccgcctaggtgaggttg |

| Primer . | Sequence (5′-3′) . |

|---|---|

| A | tcactataggctagcatggtctcc |

| B_C | cttggtcttcttggtcttctgtgtcgccttggggtttgctg |

| E_C | accaagaagaccaagtagatccgcgaattgtggggggca |

| B_IX | aaacagtctcagcgccttggggtt |

| C_IX | aaccccaaggcgctgagactgttt |

| D_IX | ccccacaattcgagtgaagtcat |

| E_IX | atgacttcactcgaattgtgggg |

| B_X | tgggccactgagccttggggttt |

| C_X | aaaccccaaggctcagtggccca |

| D_X | ccccacaattcgggtgaggttgtt |

| E_X | aacaacctcacccgaattgtgggg |

| D_X1-34 | ccacaattcggtcgaaggggttct |

| E_X1-34 | agaaccccttcgaccgaattgtgg |

| B_X30-52 | aaggggttctcgccttggggttt |

| C_X30-52 | aaaccccaaggcgagaacccctt |

| F | taaagggaagcggccgcctagggaaat |

| NNAAfwd | gcttgacttcgcccagacgcagcctgagaggggcgacaacgccctcacccg |

| NNAArev | cgggtgagggcgttgtcgcccctctcaggctgcgtctgggcgaagtcaagc |

| TTAAfwd | gacagcatcgcatggaagccatatgatgcagccgacctggaccccgccgagaacc |

| TTAArev | ggttctcggcggggtccaggtcggctgcatcatatggcttccatgcgatgctgtc |

| B_XHC | ctgggccactgagggaaatgg |

| C_XHC | ccatttccctcagtggcccag |

| D_XHC | taaagggaagcggccgcctaggtgaggttg |

Description of proteins used in this study

| Abbreviation . | Protein . |

|---|---|

| FVII | Factor VII |

| FVII_C | FVII with protein C activation peptide |

| FVII_IX | FVII with FIX activation peptide |

| FVII_X | FVII with FX activation peptide |

| FVII_X1-34 | FVII with the 34 first amino acids of FX activation peptide |

| FVII_X30-52 | FVII with the 23 last amino acids of FX activation peptide |

| FVII_XNNAA | FVII with both N-glycans removed in FX activation peptide |

| FVII_XTTAA | FVII with both O-glycans removed in FX activation peptide |

| FVII_XHC | FVII with FX activation peptide inserted at the C-terminus |

| FX | Factor X |

| FXai | Active site inhibited Factor Xa |

| Abbreviation . | Protein . |

|---|---|

| FVII | Factor VII |

| FVII_C | FVII with protein C activation peptide |

| FVII_IX | FVII with FIX activation peptide |

| FVII_X | FVII with FX activation peptide |

| FVII_X1-34 | FVII with the 34 first amino acids of FX activation peptide |

| FVII_X30-52 | FVII with the 23 last amino acids of FX activation peptide |

| FVII_XNNAA | FVII with both N-glycans removed in FX activation peptide |

| FVII_XTTAA | FVII with both O-glycans removed in FX activation peptide |

| FVII_XHC | FVII with FX activation peptide inserted at the C-terminus |

| FX | Factor X |

| FXai | Active site inhibited Factor Xa |

FVII variants containing either the 34 first amino acids (FVII_X1-34) or the 23 last amino acids (FVII_X30-52) of the FX activation peptide were created using overlap extension PCR as in “Construction of FVII variants” and primers according to Table 1 followed by insertion into pCI-neo. For the FVII_XHC variant, containing the FX activation peptide in the C-terminal end of FVII, primer pair A and B_XHC was used to amplify FVII, primers C_XHC and D_ XHC for FX's activation peptide, followed by a second PCR to generate the whole construct using primers A and D_ XHC, otherwise as in “Construction of FVII variants.” FVII_X variants lacking either the 2 N-glycosylation sites at Asn-39 and Asn-49 (FVII_XNNAA) or the 2 O-glycosylation sites at Thr-17 and Thr-29 (FVII_XTTAA) in the FX activation peptide were produced using Quick Change II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and primer pairs NNAA and TTAA forward and reverse, respectively (Table 1).

Protein preparation

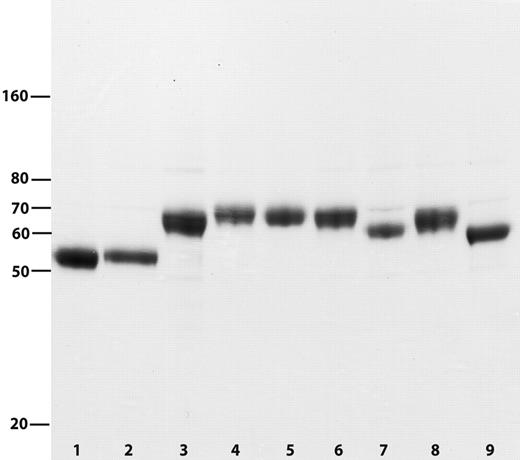

All FVII variants, including wild-type FVII, were transiently expressed in HEK-293F cells using FreeStyle 293 Expression System (Invitrogen) according to the manual; 96 hours after transfection, the cells were removed by centrifugation and the supernatants saved at −80°C until use. The expressed proteins were purified by affinity chromatography, using a Ca2+-dependent monoclonal anti-FVII antibody, F1A2, coupled to Sepharose.19 In short, the supernatants were prepared to 350mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2, pH 7, and loaded on a column, which was equilibrated with 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 100mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2 pH 7.5. The column was washed with 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 2M NaCl, 10mM CaCl2 pH 7.5, followed by elution with 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 100mM NaCl, 10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 7.5. After elution, 15mM CaCl2 was added and the protein solutions stored at −80°C. Protein purity was assessed by Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure 1) and estimated to be more than 95% homogeneous for all preparations. The amounts of aggregates in the protein preparations were quantified by size exclusion high performance liquid chromatography on a Waters Protein Pak 300 SW column (7.5 × 300 mm) and monitoring the fluorescence signal at 340 nm (excitation wavelength 280 nm).

Active site inhibited FXa (FXai) was prepared as follows: 30μM FXa was incubated with 65μM Glu-Gly-Arg-chloromethylketone at room temperature for 2 hours (residual amidolytic activity < 0.5%) and then desalted on a NAP-5 column (GE Healthcare) into 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 100mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2, pH 7.5. FX was buffer-exchanged to the same buffer. Protein concentrations were determined by absorbance measurements at 280 nm using absorption coefficients of 1.16 for a 1-mg/mL solution of FX and 1.32 for all FVII variants.

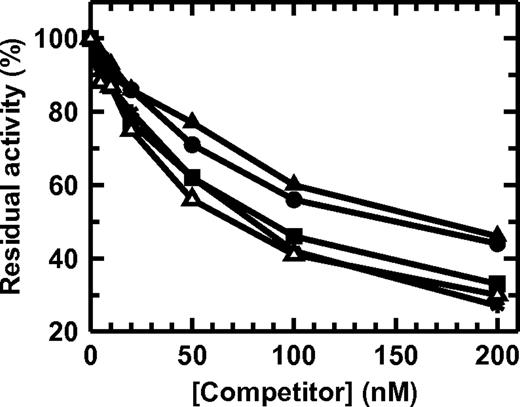

The sTF-binding properties of the FVII variants were tested by incubating them at various concentrations (5-200nM) with 4nM sTF for 5 minutes. After this, 10nM FVIIa and 1mM S-2288 were added and the amidolytic activity measured at 405 nm using a kinetic microplate reader (SpectraMax 384Plus, Molecular Devices). The activity of 10nM FVIIa in the absence of sTF was subtracted to obtain the sTF-dependent FVIIa activity, and the FVIIa:sTF activity obtained in the absence of FVII variants was defined as 100%. None of the FVII variants exhibited detectable activity in the presence of sTF.

Pharmacokinetics

Male NMRI mice (Taconic M&B) weighing approximately 25 g were acclimated for at least 7 days at the animal facility at Novo Nordisk A/S, Måløv under standardized conditions, 12/12 hour light/dark cycle, 21°C, 60% relative humidity, watered, and fed ad libitum. The study was performed according to guidelines from the Danish Animal Experiments Council, the Danish Ministry of Justice. Mice were dosed 1 mg/kg, with the exception of FVII_C (0.5 mg/kg), as a single intravenous bolus in the tail vein and blood was obtained according to a sparse sampling design as previously described,22 including 3 blood samples per mouse and 2 or 3 mice per time point. The mice were anesthetized by isoflurane/O2/N2O for blood sampling, and 4 droplets of blood were sampled from the orbital plexus using a capillary glass tube at t = 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 hours after administration of FVII, FVIIa, and FXai, and at t = 0.08, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 3, 7, 17, 24, and 30 hours after administration of all other proteins investigated. Blood (45 μL) was immediately transferred to 5 μL 0.13M trisodium citrate solution and diluted 5 times in 0.01M sodium phosphate buffer, 0.145M NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 1% bovine serum albumin, pH 7.6, followed by centrifugation at 4000g for 5 minutes at room temperature. The supernatant representing diluted plasma was collected, placed on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until analysis by FVII or FX ELISA. Briefly, FVII antigen concentrations were determined by the FVII-ELISA (Dako). This 2-site monoclonal immunoenzymatic assay with peroxidase as the marker enzyme was performed as described by the manufacturer. FX antigen concentrations were determined by the FX-ELISA using a modified commercially available kit from Haemochrom Diagnostica. Briefly, diluted plasma samples were incubated in microwells coated with a polyclonal antibody specific for FX. After a washing step, polyclonal FX antibody coupled to peroxide was added. After a washing step, a substrate (TMB) in the presence of H2O2 was introduced and the color developed. The reaction was stopped with sulfuric acid, and the amount of color developed was directly proportional to the concentration of FX in the tested sample. For the initial study, the terminal half-life was estimated by noncompartmental methods (WinNonlin Pro Version 4.1; Pharsight). For the second study, pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using a population approach using nonlinear mixed effect modeling through the one- or 2-compartmental FOCE method (NON-MEM Version VI).23 The interindividual variability was modeled by an exponential error model, and the intraindividual variability was modeled as a proportional error model. The quality of the fit was evaluated by graphic analysis of predicted versus observed concentrations, by weighted residuals versus predicted concentrations, and by comparison of the objective values.

Activation and activity of FVII variants

In the initial assessment of whether the FVII variants could be activated, they were incubated at 1μM in 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 100mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2, pH 7.4, at ambient temperature with 250nM FIXa for 20 hours, 100nM FXa for 2 hours, 75nM FXIa for 2.5 hours, or 100nM FVIIa together with 75nM lipidated TF for 20 hours. The samples were analyzed on SDS-PAGE run under reducing conditions. Wild-type FVII was used as a positive control and was completely activated under all described conditions.

FVII_XHC was studied in more detail by incubating 2μM of FVII or FVII_XHC with 80nM FIXa in 50mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, 100mM NaCl, 10mM CaCl2, 0.01% Tween-80, pH 7.4, at ambient temperature. Samples were taken after 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 hours and analyzed for amidolytic and proteolytic enzyme activity as well as by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. The amidolytic activity was measured by incubating 12.5nM FVII/FVII_XHC from the activation mixture with 50nM sTF and 1mM S-2288, and the hydrolysis of the chromogenic substrate was monitored continuously at 405 nm using a kinetic microplate reader (SpectraMax 384Plus, Molecular Devices). The proteolytic activity was measured by incubating 100nM FVII/FVII_XHC from the activation mixture plus 500nM sTF with 150nM FX for 10 minutes. The activity of activated free FVII_XHC (after removal of FIXa using F1A2 affinity chromatography) was assessed by incubation of 50nM enzyme with FX (0.2-10μM) for 20 minutes, and the activity of FVIIa_XHC bound to lipidated TF was assessed by mixing 0.2nM enzyme with 2pM TF followed by incubation with FX (10-640nM) for 15 minutes. All activity measurements were performed in 20mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 7.4, containing 0.1M NaCl, 5mM CaCl2, 0.1% polyethylene glycol 8000, and 0.01% Tween 80, and the reactions were quenched by adding excess ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The generated FXa was quantified by adding S-2765 (final concentration, 0.5mM) followed by continuous monitoring of the absorbance increase as described for the other chromogenic assays. Clotting activity was measured on an ACL 300 Research instrument (Instrumentation Laboratory). FVIIa or FVIIa_XHC (final concentrations 2-50pM and 10-100pM, respectively) was added to FVII-deficient plasma (Helena Biosciences), and the reaction was initiated by adding a mixture of lipidated TF (Innovin) or rabbit brain cephalin (Heptest Laboratories) and CaCl2. The recorded clotting times were between 80 and 180 seconds (buffer controls > 300 seconds). The relative clotting activity of FVIIa_XHC was determined by comparison with the FVIIa concentration giving the same clotting time (obtained from the FVIIa standard curve). FVIIa_XHC for the pharmacokinetics study was prepared by autoactivation of FVII_XHC.

Results

Pharmacokinetics of FVII variants with FX, FIX, or protein C activation peptide insert

Initially, we investigated the effect of introducing the activation peptide from protein C (12 residues), FIX (35 residues), or FX (52 residues) on FVII plasma half-life. The 3 FVII variants (FVII_C, FVII_IX, and FVII_X, respectively) were constructed so that the activation peptide was inserted immediately before the normal activation cleavage site in FVII (ie, with the C-terminal Arg residue in P1 position and occupying the position of Arg-152 in FVII). If the variants could be successfully activated, the activation peptide would remain attached as a C-terminal extension of the FVIIa light chain. An FVII variant with the first 51 residues of the activation peptide from FX (so that the insert is identical to that of FVII_X) placed at the C-terminus (FVII_XHC) was also made, and the activated form would carry a C-terminal heavy chain extension. The constructs and wild-type FVII were transiently expressed in HEK-293F cells and purified to homogeneity by affinity chromatography using a Ca2+-dependent monoclonal anti-FVII antibody recognizing the Ca2+-loaded γ-carboxyglutamic acid domain (Figure 1). To verify that the FVII variants were properly folded, their ability to bind sTF was investigated. All variants were capable of binding sTF (Figure 2). However, whereas FVII and FVII_XHC displayed normal sTF binding compared with a R152A-FVII reference, FVII_IX and FVII_X appeared to bind sTF with slightly lower affinity. This presumably results from an altered (suboptimal) distance between sTF-interactive regions on opposite sides of the inserted activation peptide preventing the complete set of native interactions to occur simultaneously or, possibly, resulting in an entropic penalty on sTF binding. In line with this explanation, the FVII_XHC variant, with a C-terminal activation peptide, which does not alter the distance between TF-interactive regions in the molecule, displays normal affinity for sTF. The preparations of FVII, FVII_IX, FVII_X, and FVII_XHC were found to contain only small amounts of aggregated material (1.5%, 1.9%, 0.8%, and 0.8%, respectively) as judged by size-exclusion chromatography analysis. Altogether, the quality of the final protein preparations was found suitable for in vivo testing.

Purified FVII and FVII variants. Reducing SDS-PAGE showing FVII (lane 1), FVII_C (lane 2), FVII_IX (lane 3), FVII_X (lane 4), FVII_XHC (lane 5), FVII_XTTAA (lane 6), FVII_XNNAA (lane 7), FVII_X30-52 (lane 8), and FVII_X1-34 (lane 9).

Purified FVII and FVII variants. Reducing SDS-PAGE showing FVII (lane 1), FVII_C (lane 2), FVII_IX (lane 3), FVII_X (lane 4), FVII_XHC (lane 5), FVII_XTTAA (lane 6), FVII_XNNAA (lane 7), FVII_X30-52 (lane 8), and FVII_X1-34 (lane 9).

TF binding of FVII variants. FVII (■), FVII_IX (●), FVII_X (▴), or FVII_XHC (▵) was incubated with 4nM sTF for 5 minutes, followed by the addition of 10nM FVIIa and chromogenic substrate. The measured FVIIa:sTF amidolytic activity is shown. The decreased residual activity at higher FVII variant concentrations indicates that TF is increasingly occupied by FVII variant. R152A-FVII (*) produced by stably transfected baby hamster kidney cells was included as a reference.

TF binding of FVII variants. FVII (■), FVII_IX (●), FVII_X (▴), or FVII_XHC (▵) was incubated with 4nM sTF for 5 minutes, followed by the addition of 10nM FVIIa and chromogenic substrate. The measured FVIIa:sTF amidolytic activity is shown. The decreased residual activity at higher FVII variant concentrations indicates that TF is increasingly occupied by FVII variant. R152A-FVII (*) produced by stably transfected baby hamster kidney cells was included as a reference.

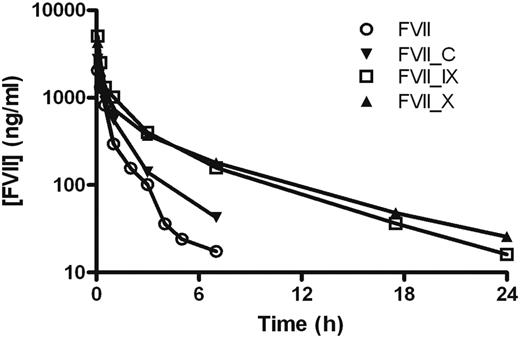

The pharmacokinetics of FVII, FVII_C, FVII_IX, and FVII_X were determined after single-dose intravenous administration to NMRI mice (Figure 3), and terminal half-lives were estimated. The elimination from the circulation of FVII resulted in an estimated half-life of 1.4 hours, which was in the same range as published data.8,24 Insertion of the activation peptide from FIX or FX resulted in a significant prolongation of FVII plasma circulation time. For FVII_IX, a half-life of 4.3 hours was determined, which is 3 times longer than for wild-type FVII, whereas the greatest effect was seen with FVII_X, which had a half-life of 5.5 hours or 4 times that of FVII. FVII_C displayed an insignificant prolongation compared with FVII with a half-life of 1.7 hours.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of FVII variants with different activation peptides. Mean plasma concentration of FVII antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg FVII, FVII_C, FVII_IX, and FVII_X to mice. Blood was sampled in a sparse schedule as each compound was administered to a total of 6 to 9 mice, and 3 samples were taken from each animal as described in “Pharmacokinetics.”

Pharmacokinetic profiles of FVII variants with different activation peptides. Mean plasma concentration of FVII antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg FVII, FVII_C, FVII_IX, and FVII_X to mice. Blood was sampled in a sparse schedule as each compound was administered to a total of 6 to 9 mice, and 3 samples were taken from each animal as described in “Pharmacokinetics.”

Influence of FX activation peptide location and structural features on FVII plasma half-life

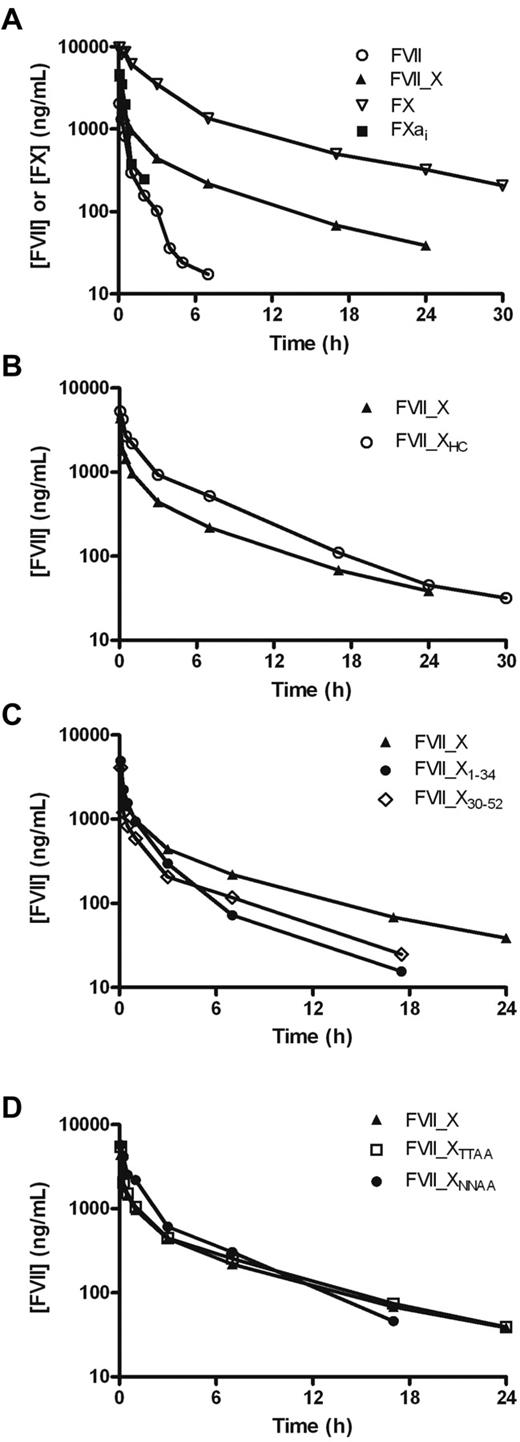

The pronounced effect on FVII plasma half-life of inserting the FX activation peptide made us pursue a more detailed structure-pharmacokinetics relationship. A number of different FVII_X variants were constructed (Figure 1; Table 2). Initially, to see whether the activation peptide of FX is as important for FX's half-life, the pharmacokinetics of an active site inhibited FXa (FXai), where the activation peptide is absent and the active site blocked to prevent inhibitor complex formation, were studied together with those of FX, FVII, and FVII_X (Figure 4A). The data were best characterized as a 2-compartment model with a rapid distribution phase and a slower disposition phase, except for FXai, where a single-compartment model fitted better to the data (Table 3). The current study was designed to explore the terminal elimination; therefore, all half-lives in the manuscript refer to the terminal half-life. The half-life of FVII_X of 6.3 hours corresponds well to our initial study and is in the same range but shorter than that of FX, which had a half-life of 8.6 hours. It is plausible that differences in the carbohydrate moieties of the activation peptide between a recombinant (FVII_X) and a plasma-derived protein (FX) account for (some of) the difference in terminal half-life. Removal of the activation peptide from FX resulted in a dramatic loss in half-life for FXai (t½ was short and estimated to 0.4 hours), which appeared to be even shorter than that of FVII (1.4 hours). The more profound reduction on concomitant removal of the activation peptide and FX activation may be the result of a conformational change leading to exposure of a binding site for low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein.12 Nevertheless, these results clearly show that the activation peptide of FX is important for a long FX half-life, in agreement with recent data on FX,25 and for prolonged FVII half-life, suggesting a role of this motif, which is largely unaffected by the protein context. To further address the environment independence of the FX activation peptide, we constructed FVII_XHC with the FX activation peptide positioned C-terminally, far from the activation site as an extension of the heavy chain generated on activation. The pharmacokinetics of this variant was compared with that of FVII_X; and, interestingly, FVII_XHC and FVII_X exhibited similar clearance profiles (Figure 4B; Table 3). The half-life of FVII_XHC was determined to 5.4 hours compared with 6.3 hours for FVII_X. The mean residence times (MRTs) of FVII, FVII_X, and FVII_XHC were estimated to be 1.0, 6.6, and 5.5 hours, respectively.

Effect of FX activation peptide and variants thereof on the half-life of FVII and FX. (A) Mean plasma concentration of FVII or FX antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg FX, FVII_X, FXai, and FVII to mice. (B) Mean plasma concentration of FVII antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg FVII_X and FVII_XHC, (C) FVII_X, FVII_X1-34 and FVII_X30-52, and (D) FVII_X, FVII_XNNAA, and FVII_XTTAA to mice. Blood was sampled in a sparse schedule as each compound was administered to a total of 6 to 9 mice, and 3 samples were taken from each animal as described in “Pharmacokinetics.”

Effect of FX activation peptide and variants thereof on the half-life of FVII and FX. (A) Mean plasma concentration of FVII or FX antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg FX, FVII_X, FXai, and FVII to mice. (B) Mean plasma concentration of FVII antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg FVII_X and FVII_XHC, (C) FVII_X, FVII_X1-34 and FVII_X30-52, and (D) FVII_X, FVII_XNNAA, and FVII_XTTAA to mice. Blood was sampled in a sparse schedule as each compound was administered to a total of 6 to 9 mice, and 3 samples were taken from each animal as described in “Pharmacokinetics.”

Estimated PK parameters

| Compound . | Comp . | Cl, mL/h per kg . | V1, mL/kg . | V2, mL/kg . | t1/2 alfa, h . | t1/2 beta, h . | MRT, h . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVII | 2 | 609 | 304 | 336 | 0.19 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| FVII_X | 2 | 176 | 244 | 966 | 0.10 | 6.3 | 6.6 |

| FX | 2 | 25 | 105 | 102 | 0.08 | 8.6 | 6.3 |

| FXai | 1 | 354 | 216 | 0.42 | 0.6 | ||

| FVII_XHC | 2 | 82 | 194 | 305 | 0.12 | 5.4 | 5.5 |

| FVII_X1-34 | 2 | 249 | 228 | 490 | 0.15 | 3.6 | 2.6 |

| FVII_X30-52 | 2 | 295 | 246 | 1080 | 0.13 | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| FVII_XNNAA | 2 | 115 | 173 | 259 | 0.16 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| FVII_XTTAA | 2 | 146 | 200 | 747 | 0.11 | 5.7 | 6.3 |

| Compound . | Comp . | Cl, mL/h per kg . | V1, mL/kg . | V2, mL/kg . | t1/2 alfa, h . | t1/2 beta, h . | MRT, h . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FVII | 2 | 609 | 304 | 336 | 0.19 | 1.4 | 1.0 |

| FVII_X | 2 | 176 | 244 | 966 | 0.10 | 6.3 | 6.6 |

| FX | 2 | 25 | 105 | 102 | 0.08 | 8.6 | 6.3 |

| FXai | 1 | 354 | 216 | 0.42 | 0.6 | ||

| FVII_XHC | 2 | 82 | 194 | 305 | 0.12 | 5.4 | 5.5 |

| FVII_X1-34 | 2 | 249 | 228 | 490 | 0.15 | 3.6 | 2.6 |

| FVII_X30-52 | 2 | 295 | 246 | 1080 | 0.13 | 4.2 | 4.4 |

| FVII_XNNAA | 2 | 115 | 173 | 259 | 0.16 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| FVII_XTTAA | 2 | 146 | 200 | 747 | 0.11 | 5.7 | 6.3 |

NMRI mice were dosed 1 mg/kg of the listed compounds intravenously.

Comp indicates the estimated number of compartments in the pharmacokinetic model; Cl, clearance; V1, central compartment; V2, peripheral compartment; t1/2alpha, distribution half-life; t1/2beta, terminal half-life; and MRT, mean residence time.

The FX activation peptide was further studied with the aim of identifying important structural features responsible for the prolongation of plasma half-life. To find out whether the whole sequence or only a part of the FX activation peptide was responsible for the extension of FVII half-life, 2 variants were constructed: one containing the first half of the FX activation peptide (FVII_X1-34) and one containing the last part (FVII_X30-52; Figure 1). It is worth mentioning that FVII_X1-34 retained Arg-152 of FVII. The pharmacokinetic study (Figure 4C; Table 3) indicated that the last 23 residues of the FX activation peptide gave a greater prolongation than the first 34 residues (MRT 4.4 hours compared with 2.6 hours and terminal half-lives of 4.2 hours and 3.6 hours, respectively). The last 19 residues have been shown to be important for the half-life of FX itself.25 The last 23 residues contain 2 N-linked glycans, whereas the first 34 residues contain 2 O-linked glycans. Glycans tend to have an overall effect of increasing the in vitro stability of proteins as well as plasma half-life and glycoengineering has thus been used in numerous studies to stabilize recombinant proteins.26,27 To address whether the carbohydrate moieties contributed to the prolonging effect of the FX activation peptide, 2 mutants were constructed: FVII_XNNAA lacking the N-linked glycans because of mutations of Asn-39 and Asn-49 in the FX activation peptide to Ala residues and FVII_XTTAA where Thr-17 and Thr-29 were changed to Ala to remove the O-linked glycans. As expected, the purified mutants displayed lower molecular weights compared with FVII_X (Figure 1). The pharmacokinetic study showed that removal of the N-linked glycans resulted in a decreased half-life of 3.8 hours (Figure 4D; Table 3), which is similar to the result when inserting the first 34 residues (half-life of 3.6 hours). The N-linked glycans appear to be at least as important in the FX context.25 The MRT and terminal half-life were both reduced by approximately 3 hours when the N-linked glycans were absent. Removing the O-linked glycans had very little, if any, effect on FVII's half-life, 5.7 hours compared with 6.3 hours for FVII_X, or MRT (6.3 hours and 6.6 hours, respectively). Thus, other features within the first 29 residues appear to be responsible for the reduction in half-life of FVII_X30-52 to 4.2 hours.

The distribution volumes (central compartment, Table 3) were generally larger than the expected plasma volume of the mouse, in agreement with previous findings in humans.4,5 This is a consequence of recoveries significantly less than 100%, which might be explained by extravasation or vessel wall adsorption of injected protein. The duration of the distribution phase was similar for all compounds and estimated to be in the range of 5 to 10 minutes.

Activation of the FVII variants and specific activity of the resulting FVIIa molecules

FVII conversion to its active form, FVIIa, requires proteolysis of a single peptide bond between Arg-152 and Ile-153, which is at the position where the activation peptide ends in all but one of the FVII variants (except FVII_XHC where the activation peptide is located C-terminally in FVII). An important question is thus whether the variants can still be activated and perform any biologic function. Initially, FVII variant activation was tested with the enzymes FVIIa (bound to TF), FIXa, and FXa, all physiologic activators of FVII. The FVII variants were incubated with high concentrations of the activators for long times, which was more than sufficient to completely activate native FVII (“Activation and activity of FVII variants”). The samples were assayed by reducing SDS-PAGE, where activated proteins would turn up as 2 bands representing a heavy chain (carrying a C-terminal activation peptide in the case of FVII_XHC) and a light chain (carrying a C-terminal activation peptide in all the other variants). The FVII_XHC variant, containing the FX activation peptide at the C-terminus, was the only variant prone to activation with FVIIa, FIXa, and FXa. In all other cases, with the exception of FVII_IX, the variants could not be activated to a detectable extent (data not shown). Activation of FVII_IX was also very slow compared with wild-type FVII and was only seen on treatment with excessive amounts of FVIIa.

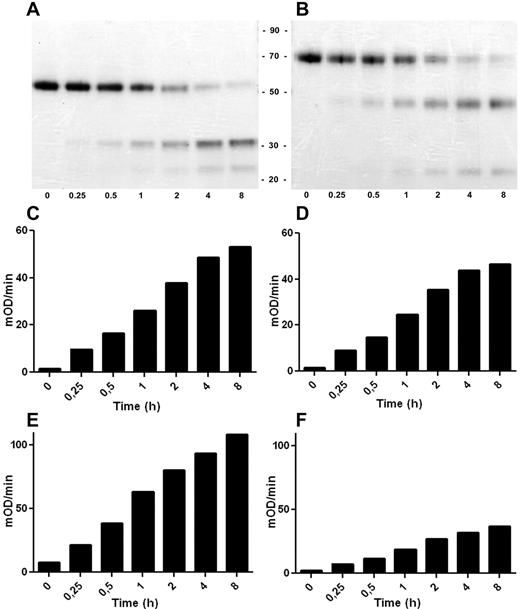

The activation of FVII_XHC was studied in more detail. FVII_XHC was found to exhibit in vitro activation kinetics indistinguishable from those of wild-type FVII when incubated with FIXa (Figure 5A-B) or FXa (data not shown). In parallel in the same experiment, the development of catalytic activity of activated FVII_XHC (FVIIa_XHC) was compared with that of activated FVII, yielding native FVIIa (Figure 5C-F). FVIIa_XHC and FVIIa bound to sTF exhibited virtually identical amidolytic activities using the chromogenic substrate S-2288 (Figure 5C-D). In addition, FVIIa_XHC bound to sTF was able to activate the physiologic substrate FX, albeit with an apparent reduction in specific activity compared with FVIIa (Figure 5E-F). The most probable explanation for the diminished proteolytic activity of FVIIa_XHC (about one-third that of FVIIa) is that the activation peptide sterically prevents optimal access of FX to the activator, for instance, by shielding a FVIIa exosite for FX. A reduced proteolyic activity of FVIIa_XHC was also measured in complex with lipidated TF and in the absence of the protein cofactor in systems using purified components (15% and 50% compared with FVIIa, respectively). We did not detect a significant effect of the activation peptide on the Km for FX either when the enzyme was bound to lipidated TF (Km = 70-90nM for both forms of FVIIa) or for the free form of the enzyme without phospholipids (Km > 5μM). Clotting assays using FVII-depleted plasma and either phospholipids or lipidated TF confirmed the lower specific activity of FVIIa_XHC (showing ∼ 30%-40% activity compared with FVIIa).

Activation and enzymatic activity of the FVII_XHC variant. FVII_XHC and FVII were incubated with FIXa and analyzed at different time points (0-8 hours). (A-B) The time courses of activation as judged by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of FVII and FVII_XHC, respectively, run under reducing conditions. The amidolytic activity of the generated FVIIa (C) and FVIIa_XHC (D) was determined by measuring the turnover of the small chromogenic substrate S-2288. FX was used as the substrate to assess the proteolytic activity of the generated FVIIa (E) and FVIIa_XHC (F) (mean, n = 3; experimental details in “Activation and activity of FVII variants”).

Activation and enzymatic activity of the FVII_XHC variant. FVII_XHC and FVII were incubated with FIXa and analyzed at different time points (0-8 hours). (A-B) The time courses of activation as judged by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of FVII and FVII_XHC, respectively, run under reducing conditions. The amidolytic activity of the generated FVIIa (C) and FVIIa_XHC (D) was determined by measuring the turnover of the small chromogenic substrate S-2288. FX was used as the substrate to assess the proteolytic activity of the generated FVIIa (E) and FVIIa_XHC (F) (mean, n = 3; experimental details in “Activation and activity of FVII variants”).

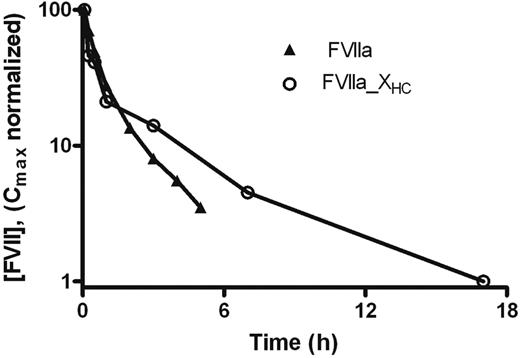

Finally, the pharmacokinetics of FVIIa_XHC were compared with those of FVIIa after single-dose intravenous administration to NMRI mice to determine whether the effects of the activation peptide on the activated and zymogen forms were similar (Figure 6). The terminal half-lives of FVIIa_XHC and FVIIa were estimated to 4.2 and 1.6 hours, respectively, with MRT values of 4.8 and 1.6 hours, respectively. Thus, the activation peptide mediates significant prolongation of FVIIa_XHC compared with FVIIa, albeit to an extent that appears to be slightly smaller than when comparing the corresponding zymogen forms.

Effect of C-terminal FX activation peptide on the half-life of FVIIa. Mean plasma concentration of FVIIa antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg FVIIa and FVIIa_XHC to mice. Blood was sampled in a sparse schedule as each compound was administered to a total of 6 mice and 3 samples were taken from each animal as described in “Pharmacokinetics.”

Effect of C-terminal FX activation peptide on the half-life of FVIIa. Mean plasma concentration of FVIIa antigen as a function of time after intravenous administration of 1 mg/kg FVIIa and FVIIa_XHC to mice. Blood was sampled in a sparse schedule as each compound was administered to a total of 6 mice and 3 samples were taken from each animal as described in “Pharmacokinetics.”

Discussion

The present data demonstrate that the insertion of an activation peptide, in particular that of FX, substantially extends the plasma half-life of FVII. The influence of the activation peptide from FX approaches that on the half-life of native FX. The fold prolongation of the terminal half-life of FVII appears to be very similar to that obtained by fusion to albumin or glycan derivatization using a 40-kDa polyethylene glycol, although the use of various species for the pharmacokinetics assessment warrants a certain degree of caution.13-15 The intriguing and unanswered question is to what extent the various strategies prolong the half-life in humans and whether the potential remains similar. In general, the level of extension obtained with various activation peptides results in a half-life of the FVII variant that roughly reflects the half-life of the parent protein from which the activation peptide was imported (FX > FIX ≫ protein C). Importantly, the impact of the activation peptide on FX's own half-life and the prolongation of FVII mediated by the FX activation peptide, supported by data with the FIX activation peptide inserted into FVII, clearly indicate that the effect of an activation peptide is not absolutely dependent on the protein environment. However, we observed a slightly longer half-life of native FX compared with that of FVII containing the FX activation peptide, even though active-site inhibited FXa was cleared at least as fast as native FVII, but the (small) differences may be the result of the different origins of the FVII variants (recombinant) and the FX derivatives (plasma-derived). Both the N- and C-terminal halves of the FX activation peptide were able to prolong the circulatory half-life of FVII, and so did the presence of the N-linked glycans. Thus, it is evident that the FX activation peptide and its carbohydrates not only prevent spurious, untimely, cofactor-independent conversion of zymogen to enzyme28,29 but also determine the plasma half-life. The fact that the murine plasma half-life of the human FVII variants containing the activation peptide from FX approached that of human FX raises the tantalizing possibility, considering the long half-life of FX in humans,9,10 that the plasma half-life of those FVII variants in humans would be considerably prolonged. However, at present this remains speculative.

It is plausible that the introduction of an activation peptide into FVII extends its half-life by hiding a region on the FVII molecule that mediates relatively rapid clearance. However, the present data suggest that the positioning of the FX activation peptide in FVII is not critical. In contrast, the observation that the half-life of FVII was similarly prolonged by the FX activation peptide in 2 different locations definitely suggests that the activation peptide confers a retention signal to its cargo protein rather than masks a clearance motif. If this is true, it would theoretically permit optimal positioning of the activation peptide, for instance, in a manner that allows for FVII to be rapidly activated and attain full FVIIa biologic activity without compromising the half-life. This warrants further work and may contribute valuable knowledge for the future construction of new variants of FVII(a) or other proteins based on the activation peptide insertion approach. The positioning of the FX activation peptide at the C-terminus of FVII (FVII_XHC) indeed resulted in wild-type FVII activation kinetics, whereas insertion of the activation peptide N-terminal of the natural cleavage site (FVII_X) obliterated activation. Activated FVII_XHC even displayed normal catalytic activity as measured using a peptidyl substrate and a prolonged terminal half-life, but the proteolytic activity toward FX was impaired, presumably the result of steric hindrance. It may be feasible to insert a smaller part of the FX activation peptide, or a variant thereof, and thereby avoid interference with FX binding and processing while maintaining the long half-life. Long-acting FVII with the potential for full hemostatic effect on activation, or fully active long-acting FVIIa, would be a valuable and competitive addition to the portfolio of hemophilia treatment options by reducing the injection frequency in prophylactic treatment of patients requiring a bypassing agent such as FVIIa.

The mechanism by which a given activation peptide influences the plasma half-life of the parent protein or of FVII is unknown but most certainly common. The effect of an activation peptide on the protein mass or hydrodynamic size is marginal, and the lack of sequence similarity between the activation peptides of FIX and FX is conspicuous. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the activation peptides are involved in some promiscuous interaction(s) that is crucial for the retention and half-life of the native factor. However, it cannot be ruled out that FIX and FX, with quite different activation peptides, exploit different mechanisms and interaction partners to achieve their relatively long half-lives (compared with that of FVII) as opposed to using a common clearance system. It is conceivable that elements of secondary and/or tertiary structure in the activation peptide are involved in regulating the half-life, and this possibility warrants further characterization of the peptide itself. In addition, because the presence of the 2 N-linked glycans in the activation peptide of FX considerably affected the half-life of FVII_X but only the first glycan is broadly conserved between animal species, it might be relevant to study the effect of removing them individually. It might also be worthwhile investigating the prolongation effect of the activation peptide of murine FX in mice to assess potential species barriers.

In conclusion, the present data clearly show the important role of the activation peptide in plasma half-life regulation and demonstrate that an activation peptide not only prolongs the half-life of its native cargo protein but also functions after insertion into a new protein environment. However, mechanistically, very little is known about how the plasma half-lives of vitamin K-dependent proteins involved in blood clotting are controlled by their activation peptide. The activation peptides have to interact with other component(s) in circulation to be able to influence (prolong) the half-life, and the receiver of the activation peptide retention signal, such as a binding protein anchored in the vessel wall or on a circulating blood cell or another plasma protein, remains to be identified. An isolated activation peptide, or a protein such as FVII with an inserted activation peptide (with native FVII as a negative control), might be used as bait to attempt to catch and identify unknown partners.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Annemette Boe Marnow, Dorthe Riis, and Anette Østergaard for excellent technical assistance and Lasse G. Lading and Dr Christian Rischel, Department of Protein Structure and Biophysics, Novo Nordisk A/S, for performing the size exclusion chromatography analysis.

Authorship

Contribution: L.J. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; D.M.K., L.H., and H.P. designed and performed research and analyzed data; and E.P. designed the study, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors are employees of Novo Nordisk A/S.

Correspondence: Egon Persson, Haemostasis Biochemistry, Novo Nordisk A/S, Novo Nordisk Park, G8.1.61, DK-2760 Måløv, Denmark; e-mail: egpe@novonordisk.com.